U.S. Government-Sponsored Radiation Research on … · U.S. Government-Sponsored Radiation Research...

Transcript of U.S. Government-Sponsored Radiation Research on … · U.S. Government-Sponsored Radiation Research...

In early December 1993, a dark chapter ofthe United States' cold war experience was

reopened when Energy Secretary HazelO'Leary responded to news media

reports about government-sponsored radia-tion research involving hundreds of humansubjects, often without their informed con-sent. At a December 7 press conference onher initiative to declassify some of the U.S.Department of Energy's (DOE) nuclearresearch records, O'Leary commented on aseries of articles about plutonium injectionexperiments involving 18 subjects publisheda month earlier in the Albuquerque Tribune[1]. O'Leary acknowledged that these andother experiments beginning in the 1940sinvolved 600 to 800 subjects and that herdepartment would soon begin to declassifyand release documents concerning these andother experiments, which were sponsored bythe DOE's predecessors, the ManhattanProject, Atomic Energy Commission (AEC),and the Energy Research and DevelopmentAdministration (ERDA) [2].

In the following weeks, new details

uncovered in media reports about radiationexperimentation and the Energy Secretary's(Fig 1) call for "full disclosure" and her can-did statement that "For people who werewronged ...it would seem that some compen-sation is appropriate," led to a crescendo ofpublic interest and an escalation of the feder-al government's response [3]. The EnergyDepartment opened a toll-free telephonenumber to collect information from peoplewho believe they were subjects in improper-ly conducted radiation experiments.Thousands of people have been unable to getthrough to the hot line, which has beenreceiving as many as 700 calls an hour [4]. Atthe time this article was written, fiveCongressional committees had also beguninquiries into the disclosures [5,6].

The focus of the interagency investiga-tions, Congressional interest, and newsmedia coverage currently centers on a set ofgovernment-sponsored radiation experi-ments involving at least 695 human subjectsfrom the mid-1940s into the 1970s, most ofwhich were originally documented in a 1986Congressional staff report issued byRepresentative Edward Markey (D-MA) [7].These experiments include: 1) approximately800 pregnant women administered radioac-tive iron at Vanderbilt University, Nashville,Tennessee, in the late 1940s [8]; 2) nearly 200cancer patients exposed to high levels, up to200 rads, of whole-body gamma radiation atOak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge,Tennessee [9]; 3) 18 persons injected withplutonium at Oak Ridge, the University ofChicago, and the University of California at

4 Medicine & Global Survival 1994; Vol. 1, No. 1 Government-Sponsored Radiation Research

U.S. Government-Sponsored RadiationResearch on Humans 1945-1975

Michael McCally, MD, PhD, Christine Cassel, MD, Daryl G. Kimball

At the time of publication, MM was HealthProgram Officer, Chicago Community Trust, andLecturer in Medicine, University of Chicago,Chicago, IL USA; CC was Chief of the Section ofGeneral Internal Medicine, Director of theCenter on Aging, Health and Society, andProfessor of Medicine and Public Policy,University of Chicago, Chicago, IL USA; DGKwas Associate Director for Policy, Physicians forSocial Responsibility Washington, DC USA.

© Copyright 1994 Medicine and Global Survival

§

San Francisco [7]; 4) 57 inmates at the OregonState Prison whose testicles were irradiatedbetween 1963 and 1971 [7]; 5) 64 inmates atthe Washington State Prison involved in asimilar study to determine the radiation dosenecessary to produce temporary sterility [7];6) 11 terminally ill cancer patients injectedwith radioactive calcium and strontium atColumbia University and MontefioreHospital, New York City, in the late 1950s todetermine the rate at which radioactive sub-stances are taken up by human tissues [71;and 7) 19 mentally retarded teenage boys at astate school in Massachusetts who, withoutconsent, were exposed to radioactive ironand calcium in nutritional studies [8].

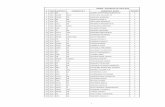

Investigators are also interested in inten-tional releases into the environment of radia-tion from government nuclear weaponsplants, which threatened the health of plantemployees and nearby populations.Information about one such experiment,known as the Green Run, began to emerge inthe mid-1980s. Details about the Green Runand 12 other releases of radioactivity at threesites in three other states (Utah, New Mexico,and Tennessee) were documented in aGovernment Accounting Office (GAO) reportreleased on December 16, 1993, by SenatorJohn Glenn (D-OH) [10]. With the exception ofthe Green Run, these tests were unknown tothe public before the release of this report. Fora more comprehensive summary of humanand environmental experiments, see Table.

The willingness of the Department ofEnergy and the Clinton White House to dis-close the records of human radiation researchis new, but families, journalists, and investi-gators have known of some of the experi-ments for many years. Many of these experi-ments have been reported in the open med-ical research literature. Public interestgroups, journalists, and science writers havedescribed many of these experiments on thebasis of interviews with subjects and families[11-15]. In proceedings well covered in thepress, the work of Eugene Saenger, aCincinnati radiologist, was brought beforethe American College of Radiology in the late1960s. Eugene Saenger was cleared of uneth-ical conduct in irradiating cancer patientswithout informed consent for military andspace science, not medical, objectives [9].

However, the government agencies, uni-versities, hospitals, and the scientistsinvolved have long resisted release of anyinformation concerning these studies. InFebruary 1987, in response to RepresentativeMarkey's committee report, "AmericanNuclear Guinea Pigs," the EnergyDepartment rejected the report's conclusionsand strongly rejected recommendations for

follow-up studies and compensation, stating:

There is no scientific reason toexpect that any of the subjects who arenot already being monitored will incurany harmful effects. Therefore, there isneither any reason for attempting anyfurther follow-up studies on these sub-jects, nor to propose new legislation tocompensate them [16].

Many DOE critics, includingRepresentative Markey, contend that thereport fell upon "deaf ears" partly because itmight have threatened the Reagan administra-tion's nuclear arms buildup of that period [16].

Barton Hacker, a historian working forthe Department of Energy, began his officialagency history with his volume, Dragon's Tail:Radiation Safety in the Manhattan Project1942-1946, published in 1987, that hinted atbut did not describe human experimentation.The book does make clear that early radiationscientists had a much clearer idea of radiationhealth effects, including cancer, than presentapologists allow [17]. Barton Hacker's secondvolume, Elements of Controversy: A Historyof Radiation Safety in the Nuclear TestProgram, was to have been published by theUniversity of California Press in 1989 [18].This book, which will be very useful in under-standing the human experimentation pro-grams, has been denied approval by theDepartment of Energy and is still unpub-lished, according to author Catherine Caufieldand Argonne laboratory scientists [19].

Because there is no single repository forhuman radiation research, the files are heldby government agencies, universities, hospi-tals, and private contractors. Many tens, ifnot hundreds, of additional governmentsponsored experiments involving radiationexposure may have been conducted. The fullextent of radiation research on humans willnot be known for months, possibly years. TheDOE and other agencies argue that release ofmany relevant documents will require theirdeclassification. There is an active debatewithin government about whether and howlong research materials ought to remain clas-sified. Given the harm that was evidentlydone, the likelihood of litigation, and publicconcern about environmental radiation cont-amination, it is likely that this story willunfold in Congress and the courts over aperiod of years.

Concerns Raised By theDisclosures

Several issues ought be kept in mind aswe seek to understand what happened andwhy it happened. Full disclosure is the first

6 Medicine & Global Survival 1994; Vol. 1, No. 1 Government-Sponsored Radiation Research

and most important task. What was done,when, and to whom? It seems clear that inmany of these studies the subjects were notfully informed, if at all, about the nature ofthe research and risks that it might entail. Allthe research subjects who are still alive clear-ly deserve to be informed. Subsequent med-ical care for these subjects may be altered onthe basis of knowledge of their prior radia-tion exposure. The provision of adequatemedical follow-up will be an important crite-rion in the evaluation of these experiments. Ifevidence can be developed that subjects wereharmed or wrongly experimented upon,compensation will be appropriate. Nationalsecurity can no longer be used as an officialreason for not releasing complete informa-tion concerning these investigations.

Second, were the experiments ethical bytoday's or prior standards? What judgmentsand rationales did the research scientists use?Most importantly, do we have adequate pro-tections and procedures in place for subjectsin human experimentation in the future?

Third, can scientists in military or other"mission" agencies conduct human experi-mentation at all, or are conflicts of interestinevitable and unresolvable? What are theright policies for conduct of human researchby the military?

A final task will be to reassure the publicthat radiation and nuclear medicine, withappropriate safeguards, currently have aunique role in medical diagnosis and treat-ment. Public fear of radiation and mistrust ofthe government and even of physicians willbe heightened by these disclosures.Physicians must reaffirm the benefits and rel-ative safety of current medical uses of radia-tion and nuclear medicine while acknowledg-ing the inappropriateness and harm of someof the experimentation now being disclosed.

Scope of the Problem: Who WasAffected?

At the outset of an investigation intoradiation research experimentation it will benecessary to establish what specific types ofresearch are to be included. These definitionswill not be easy. In addition to the radiationresearch subjects, other groups of Americanshave been exposed to radiation in govern-ment-sponsored programs since the testingof the first atomic bomb in 1945: the atomicveterans, the downwinders, MarshallIslanders, uranium miners, and nuclearweapons production workers. Many agencieshave sponsored radiation research in addi-tion to the Department of Energy (and its pre-cursor agencies: the AEC and the EnergyResearch and Development Agency [ERDA])

including the Department of Defense (DOD),the National Aeronautics and SpaceAdministration (NASA), the VeteransAdministration, the Department of Healthand Human Services (DHHS) (formerly theDepartment of Health, Education andWelfare), and the Central IntelligenceAgency (CIA).

In January, President Clinton establisheda Human Radiation Interagency WorkingGroup to coordinate a government-wideeffort to discover the "nature and extent" ofgovernment-sponsored experiments involv-ing exposure to ionizing radiation. The Groupincludes the Secretaries of Energy, Defense,Health and Human Services, and VeteransAffairs, the Attorney General, theAdministrator of NASA, and the Directors ofthe CIA and the Office of Management andBudget (OMB). The group will be supportedby the Advisory Committee on HumanRadiation Experiments. The advisory com-mittee will be led by Ruth Faden of JohnsHopkins University School of Hygiene andPublic Health. The review is intended to belimited to intentional exposures of individu-als or environmental releases of ionizing radi-ation [20].

Other government research programsinvolving human experimentation might log-ically be included in a comprehensivereview, such as studies done in the develop-ment of chemical and biological weapons andcountermeasures to their use. Little is knownpublicly about these highly classified pro-grams. According to a National Academy ofSciences report in 1993 [21], more than 4,000military recruits were used to test mustardgas and other agents in tests during and afterWorld War II. Some propose that the subjectto be reviewed is all government-sponsoredtesting programs involving human subjects,including the testing programs of the Foodand Drug Administration. However, the pre-sent investigation is likely to be limited bythe Clinton administration to the humanradiation experimentation issue.

Relationship To Environmentaland Occupational RadiationExposures

The sudden attention cast upon thecases of human radiation experimentationhas renewed concern about other U.S.nuclear weapons activities that exposed largepopulations to radioactive and toxic materi-als [8,22]. Now that Energy Department andadministration officials have begun toacknowledge the errors of past human radia-tion experimentation, explore compensationschemes, and declassify long-hidden records,many persons are seeking a renewed inquiry

Government-Sponsored Radiation Research McCally/Cassel/Kimball 7

and better response to the concerns andclaims of people subjected to radiation expo-sure through other government nuclearweapons activities. These exposures include:

* Population exposure, eitherthrough atmospheric weapons tests orair, water, and soil contamination atnuclear weapons production plants."Downwinders" refers to all those indi-viduals who were exposed to radioac-tive fallout during the atmospherictesting program of nuclear weapons inthe United States from 1945 to 1963, aprogram halted by the signing of theLimited Nuclear Weapons Test BanTreaty. Hundreds of thousands of peo-ple, principally in Nevada, Utah, andArizona, were exposed to fallout fromatmospheric weapons tests (Fig 2). Atleast seven major epidemiologic stud-ies on these downwinders have founda significant association between theradioactive fallout from atmosphericbomb tests in Nevada and anincreased incidence of leukemia[23,241. Off-site radioactive and toxiccontamination has been discovered atnine of the major nuclear weaponscomplex facilities [25], and federal andstate health agencies have only recent-ly begun studies that are designed toreconstruct exposure levels at fivefacilities and attempt to ascertainwhether the exposures have led toadverse health outcomes [26].

* The Marshall Islanders, whowere exposed to fallout from atmos-pheric tests of nuclear weapons con-ducted by the United States in theSouth Pacific in the 1950s. The HouseCommittee on Natural Resourcesholds information suggesting that thefallout from the testing was morewidespread than previously believed[21]. Research since 1990 suggests thatthyroid nodularity and cancer is pre-sent in excessive rates among theexposed islanders [27].

* Nuclear weapons plant workers,including approximately 600,000 per-sons who have worked since 1945 inthe DOE's nuclear weapons plants.Worker exposures have been underre-ported and poorly monitored, andmedical data relating to these expo-sures have been kept secret from inde-pendent investigators. DOE-ledresearchers have failed to follow upfindings that suggest positive associa-

tions between worker exposure andcancer morbidity and mortality [28].

* The atomic veterans, those mili-tary personnel who were marched intotest areas immediately followingnuclear weapon detonations in theSouth Pacific (Fig 3) and at the nuclearweapons test site in Nevada in the1940s and 1950s. As many as 250,000U.S. troops were exposed to nucleartest radiation during the 17 years ofatmospheric nuclear weapons testing[29]. The specific purposes of thesemilitary exercises varied, but all werelinked to improving the U.S. military'scapacity to conduct military actions ina nuclear war environment [14]. In1980 the Centers for Disease Control(CDC) released the first health study ofthe nuclear veterans in which theleukemia rates were twice the expect-ed rate [30].

These population-centered experiments,like most of the human experiments andintentional environmental exposures, wereconducted without the informed consent ofexposed populations and often with theknowledge that the exposures put humanhealth at risk. In the case of military exercis-es, even if soldiers were informed of knownrisks, they may not have been in a position todisobey orders of their superiors. The popu-lation-centered exposures, particularly thoseaffecting workers and off-site populations,were rarely followed by adequate medicalmonitoring of at-risk groups [28]. Therewould seem to be little moral distinctionbetween the cases of intentional human andenvironmental radiation experimentationand other, population-centered radiationexposures that resulted from nuclearweapons design, production, and testingactivities. Consequently, as Congress, theEnergy Department, administration officials,and others seek to address the human radia-tion experiments, these agencies should atthe same time place a high priority on con-ducting follow-up studies and providingmedical information for all populations sub-ject to radiation exposure.

The Need to Evaluate IndividualStudies

The human radiation research studiesappear to cover a.broad ethical spectrum.Some will warrant comparison to experi-ments on concentration camp inmates,whereas others were scientifically justifiedand ethically sound. To establish a basis forcompensation, each study will require an

8 Medicine & Global Survival 1994; Vol. 1, No. 1 Government-Sponsored Radiation Research

individual assessment. It will be important toidentify and consider the purposes of theexperiment, the quality of the research design(if any), the intended use of the informationgained, the character and competence of thesubjects, the use and quality of informed con-sent, and whether there was appropriatemedical follow-up.

The aims of the research varied. A num-ber of the studies were clearly performed formilitary purposes. In the aftermath ofHiroshima, during the period of atmospherictesting, the military and the nuclear weaponsproduction industry sought informationabout the biological activity of plutoniumand the radioisotopes of atmospheric fallout.The toxicity of plutonium was of particularconcern because the metal was extractedfrom reactor rods and milled and machinedfor bomb components. Some former AEC sci-entists claim that plutonium administrationto human subjects was used to gather infor-mation for setting safety standards forweapons production workers and scientists.Plutonium has no medical uses [31].Information on radioiodine, strontium,cesium, and other fallout isotopes was soughtto justify the unfounded claims of the safetyof atmospheric nuclear testing.

In the 1950s, military scientists soughtinformation about sublethal and lethal radia-tion doses of direct gamma (X-ray) radiationfor the design of radiation weapons, the neu-tron bomb, and battlefield nuclear weapons,as well as to support technology for fightingin areas of high radioactive fallout [32-34].Studies in which soldiers marched into areasunder atmospheric nuclear weapons detona-tions clearly served only military purposes.As biological science, the research objectivesclearly could have been accomplished by ani-mal studies or simulations. No clear scientif-ic or military justification for these humanexposures has been offered [12-14]. Finally,the manned space program and PresidentKennedy's challenge to place a man on themoon created the requirement to investigatethe effects of large bursts of gamma radiationthat unprotected astronauts might receivefrom solar flares. Testicular function was ofparticular concern because the astronautswere all young men in the prime of theirreproductive years [35].

Human studies for military or spaceflight requirements can easily be distin-guished from studies for the purposes ofimproving medical diagnosis and treatment.Occasionally, medical treatment was used bygovernment scientists or sponsors as a justifi-cation for research whose purpose was mili-tary. For example, at Oak Ridge, a facilitywas constructed in the 1960s for the adminis-

tration of whole-body gamma radiation tohuman beings. Cancer patients were givensublethal (100 to 300 rad) whole-body dosesin various exposures and their responsesstudied. Although the patients did in facthave terminal cancer, the research protocolswere not designed as tests of advanced can-cer therapy. The results of these investiga-tions were published in military medicaljournals and conferences and are not in thecancer therapy literature [33,34,36].

It should be noted that several of thestudies reviewed in the Markey subcommit-tee report were done in leading medicalresearch facilities by highly regarded medicalexperts. Informed consent consistent withpre-1976 standards was obtained and onlytrace amounts of radioactive material wereused. The information sought was clearly forimprovement of medical therapy, as, forexample, in the diagnosis and treatment ofthyroid disease where radioiodine is today astandard agent.

The Scientists' MotivesScientific motivation and behavior must

also be criteria in review of these cases. Theclaim has been reported in the press that theethical standards for the conduct of medicalresearch were different 40 years ago and, fur-ther, that cold war military threats justifiedhuman experimentation [37]. But the ethicalprinciples of scientific research were notinvented recently. The Nuremberg Principlesarising from the trial of Nazi war criminalsfor crimes including cruel and lethal humanexperimentation were well known to allAmerican scientists as soon as they werepublished in 1949 [38,39]. American scientistsdoing hazardous human experimentation inAir Force and NASA laboratories referred tothese principles and published standards forthe conduct of research in which humanswere subject to dangerous aerospace envi-ronments [40]. In a 1950 memorandum to Dr.Shields Warren, the chief medical officer ofthe AEC, Dr. Joseph Hamilton, a SanFrancisco neurologist and scientist in the plu-tonium injection studies, suggested that theexperiments might have "a little of theBuchenwald touch," reflecting clear under-standing of medical experiments by Naziprison camp doctors [41].

However, in 1945, there were no clearstandards of informed consent or mecha-nisms for monitoring the process of obtainingand documenting such consent. Scientistswere considered to be responsible and, whenfull disclosure was not made, rationalizationsabout patient's peace of mind or minimal riskwere common. In some cases, national securi-ty was blanket permission for secrecy and

Government-Sponsored Radiation Research McCally/Cassel/Kimball 9

even deception in research practices.Foregoing the Nuremberg principles wasdone with a larger good in mind. For thesereasons, when the individual studies areexamined, particularly those with clear mili-tary sponsorship and purpose, it may be dif-ficult to establish their compliance withNuremberg principles.

The Comparison to Nazi CrimesAs these research studies have come to

public attention, some commentators havelikened them to the experiments conductedby Nazi physicians in concentration campsduring World War II. This kind of compari-son deserves thoughtful scrutiny.

Although many of the U.S. radiationexperiments were clearly or questionablyunethical, none of the experiments under dis-cussion here is truly comparable to the Naziexperiments. The Nazi concentration campswere part of an explicit program of genocide,or what today might be called "ethnic cleans-ing." The overall goal was to destroy cate-gories of "undesirable" persons, predomi-nately Jews, but also Gypsies and otherminorities. The so-called experiments, most

of which had little or no scientific basis,and which produced little useful scientificknowledge, were inflicted on inmates whowere condemned to die and conducted insadistic ways in which pain and sufferingwere not in any way prevented.

The moral outrageousness of the Naziexperiments is so great that it deserves to beset aside as a special and horrible reminder ofhuman evil in our own time. Many of theradiation experiments that have come to lightin the U.S. are unethical. We understand thatthe researchers' judgment was distorted bythe conflict of interest created by the cold warmentality and the scientific imperative.However, these incidents are nowhere nearthe magnitude of the Nazi atrocities. We risktrivializing our memory of the Nazi historyto compare these radiation experiments tothe Nazi tests with humans. It serves as asomber reminder, however, of the suscepti-bility of physicians and scientists to the temp-tation to overlook the rights and welfare ofhuman subjects in the presence of conflictingincentives and social and peer pressure. Howfar this temptation can go is documented instudies of Nazi physicians [42].

One important parallel between some ofthe U.S. radiation experiments and the exper-iments of Nazi doctors is the allegiance of thephysician to the state, or the government,which obscures their responsibility to thewell-being of patients or subjects. (Of course,in the Nazi examples, there is no way the vic-tims can be considered "patients.") This sus-

ceptibility to conflict of interest is the reasonfor the absolute need for external review ofthe ethics of research with human beings,and for especially careful review in experi-ments funded by agencies like DOE or DODwhere the primary mission is not related tohuman health.

SecrecySecrecy is perhaps the central problem in

this episode. If these experiments hadreceived open discussion in the scientificcommunity, including the importance of theinformation sought, alternative sources ofinformation, experimental design, potentialrisk to subjects -- all those issues that concerncurrent day institutional review boards (IRBs)-- might well have resulted in the studiesnever having been done or being done verydifferently, with greater concern for fullyinformed consent and protection of subjects.The argument has been made by Physiciansfor Social Responsibility and others that sci-entific oversight responsibility for radiationeffects research ought to be housed in a healthagency and be subject to open, independent,nongovernmental scientific review, as federalstatute requires for all other human experi-mentation [28,431. This proposal needs to bestrongly reconsidered today.

It is ironic that while these studies havebeen secret, in that the government wouldnot release information about their existenceor the names of subjects or any other details,the results of many of these studies have beenpublished in the open scientific literature andhave always been available to knowledgeablescientists. Some radiation scientists involvedin the studies now claim that because someresults of these studies were published theynever were secret, a somewhat disingenuousposition after decades of official obstructionof public efforts to gain the information thatthe Department of Energy is now releasing.Several AEC memos confirm that it wasagency policy to make no statement concern-ing radiation experiments.

Background: The Ethics of HumanExperimentation

Three generalizations can be madeabout the ethics of the radiation researchexperiments. First, many of these studiesmust be viewed in the historical context inwhich different standards of informed con-sent were prevalent, but some of them mustbe considered unethical even when viewedwithin the appropriate historical context. It isvitally important to consider each such inci-dent separately. Second, the major historicalreality that led to the unethical conduct ofresearch in those instances where it occurred

10 Medicine & Global Survival 1994; Vol. 1, No. 1 Government-Sponsored Radiation Research

was the culture of secrecy and deceptionwithin DOE and military research units.Third, the most important goal in the openexamination of these events should be thecreation of guidelines that would preventabuses from occurring in the future.

Informed ConsentThe primary ethical principle of research

with humans is informed consent. This hasbeen a fundamental standard in medical carefor almost a century, articulated by the courtsas well as by professional societies. Thus,even when a medical treatment is indicatedto treat a disease from which the patient issuffering, and no research is involved, it isstill required that the patient be fullyinformed about risks, benefits, and alterna-tives and that he be permitted to refusepotentially beneficial treatment. BeforeWorld War I, the American jurist BenjaminCardozo articulated the doctrine as follows:"Every human being of adult years andsound mind has a right to determine whatshall be done with his own body" [44].

The doctrine of informed consent grewwithin case law after World War II as part ofthe growth of malpractice litigation. It wasestablished that physicians were required toinform patients of potential risks of medicaltreatments. Since it is virtually never possiblefor a layperson to be as well informed as thephysician about complex medical issues, thestandard of informed consent that developedwas the "community standard," i.e., thephysician was required to disclose only asmuch as was the standard of practice byother physicians in his community. In med-ical treatment the best interests of the patientsthemselves are the motivation for whateverrisks are involved; in most research the bene-fit is to other, future, and unknown personsand, therefore, the subject's participationrequires even more rigorous ethical stan-dards, especially that of informed consent, toensure respect for the person.

Hans Jonas has eloquently argued thatmedical research is an optional human goal ofrelative rather than absolute value, because itrisks objectifying and using another humanbeing for purposes that are not his or her own[45]. Every major ethicist writing abouthuman research argues that it is dangerous tothe moral fabric of society to consider poten-tial social goals as higher values than respectfor the individual, especially in the frame-work of research potentially affecting thephysical or psychological integrity of the per-son. Individuals are called on to relinquishautonomy in society for goods that they rec-ognize as social, such as civic government,education, and public health standards.

Becoming the subject of someone else's exper-iment, however, is such a dramatic infringe-ment of personal civil rights that it may bedone ethically only in the context of fullyinformed consent and voluntary altruism.

The centrality of informed consent to theethical use of human subjects in research wasestablished as an internationally acceptedprinciple by the Nuremberg MilitaryTribunal in 1949, reiterated by the HelsinkiCode of the World Medical Association in1963, and updated in 1975 [38,46]. In additionto requiring the informed consent of the sub-ject, these codes require that the experimentbe of worthy enough scientific value to justi-fy any -- even minimal -- risk to the subjects,that the investigators guard the subjectsagainst all possible foreseeable pain, suffer-ing, or disability, and that the subjects be ableto withdraw from the study at any time. It islikely that most medical investigators in the1950s knew the Nuremberg Code; but untilthe 1960s, there was no law in the UnitedStates that specifically protected the rights ofthe subjects of medical research [47].

Government OversightFederal oversight of research with

human subjects began in the United Stateswith the 1962 amendments to the FederalFood, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, whichrequired that the investigator obtain the con-sent of the subject to receive an experimentaldrug "...except where they deem it not feasi-ble or, in their profession al judgment, con-trary to the best interests of such humanbeings..." (FFDCA, Section 5 5 [i]) The regula-tions promulgated in 1966 allowed for noexceptions to the informed consent rule in"nontherapeutic" research, i.e., that whichoffered no possibility of treating a disorderthat the subject suffered from.

In 1966, the National Institutes of Health(NIH) adopted requirements that each insti-tution receiving federal funds provide assur-ance of the existence of a system of peerreview that ensured that studies protect therights and welfare of the subjects, obtaininformed consent, and have a reasonableassessment of risk and potential benefits ofthe research. These three stipulations are atthe core of both the Nuremberg Code and theHelsinki Declaration.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, numer-ous unethical human research practices byrespected, and often federally funded,researchers were disclosed. A classic articleby Henry K. Beecher in 1966 in the NewEngland Journal of Medicine cataloguednumerous such research projects [39]. TheTuskegee study came to light, in which effec-tive treatment of syphilis had been withheld

Government-Sponsored Radiation Research McCally/Cassel/Kimball 11

from a cohort of black men for more than 25years after the discovery of penicillin in thename of medical research. Jay Katz, Professorof Law and Psychiatry at Yale, was a memberof the commission appointed to study theTuskegee project, which led to the NIH rec-ommendations for stronger national regula-tion of human research [48]. Katz subse-quently published his compendious bookExperimentation with Human Beings [49].

The National Commission for theProtection of Human Subjects ofBehavioral and Biomedical Research

In 1974 the U.S. Department of Health,Education, and Welfare appointed a NationalCommission for the Protection of HumanSubjects of Behavioral and BiomedicalResearch. The commission delivered its finalreport in 1978, recommending, among otherthings, that every institution receiving anyfederal funds review all research projectsprospectively to ensure ethical treatment ofhuman subjects [50]. Each proposed projecthad to document the content of this review,as opposed to the earlier general institutionalassurances of process. The committees thatdo this are referred to now as InstitutionalReview Boards or IRBs.

The National Commission also recom-mended the creation of a standing body thatwould review federally funded research at anational level. Thus, the Ethics AdvisoryBoard was established by NIH to review newor particularly complex kinds of researchsuch as in vitro fertilization and fetal tissueresearch. Although it was intended to be anongoing body, it was disbanded in 1980 byDHHS. A new charter for the Ethics AdvisoryBoard was approved in 1988, but was neversigned by the president. A recent Office ofTechnology Assessment (OTA) study hasstrongly recommended the creation of a per-manent, ongoing national research reviewboard to consider the ethical implications ofcertain protocols or classes of federally fund-ed biomedical and behavioral research [51].Requiring any research linked with militaryor national security operations to undergoreview by such a body would be a logicalstep toward prevention of future unethicalresearch obscured from public view by poli-cies of secrecy and nondisclosure.

In light of this history, any research donebefore 1976 was not likely to have beenreviewed by an impartial body concernedabout the protection of human subjects [37].Without the IRB mechanism, conflict of inter-est is a serious problem, and even well mean-ing investigators may have overlooked ethicalissues. Especially if it was expected that noharm would come to the subjects, as in many

of the studies that used radioactive isotopes asmetabolic tracers, investigators probably tooka paternalistic stance, assuming that there wasno need for the subjects to know that radioac-tivity was being used. IRBs today, however,would insist that subjects be given this infor-mation, even if the investigators were sure thematerial was harmless. (In the 1950s whenmany of these studies were done, less wasknown about radiation effects, particularlylong-term effects, so it is incorrect, withoutanalysis of the individual studies, to describethe investigators as knowing whether or notradiation doses were harmless.)

Standards Applied to RadiationResearch

Informed ConsentValid informed consent requires: 1) that

the subject be given full information aboutthe study to be performed, and, if it is a ther-apeutic study, about the alternative treat-ments available; 2) that the subject be compe-tent to understand the information renderedand able to make a decision for himself; and3) that the decision be free and uncoerced.

Thus, any study in which people werenot given full information violates this stan-dard. Studies involving mentally ill or cogni-tively impaired subjects usually violate thesecond standard. Many ethicists believe thatresearch on prisoners violates the standard ofnoncoercion because of the inherent vulnera-bility of institutionalized persons, especiallythose incarcerated involuntarily, who mightbelieve that they would be punished for notparticipating or that their treatment might bebetter if they do. The Washington andOregon studies of testicular radiation areexamples of this problem, i.e., would an aver-age "man on the street" have agreed to takepart in these experiments?

Risk-BenefitThe National Commission in its 1976

report charged the IRBs with assessing twoethical standards in addition to informed con-sent: risk-benefit analysis and justice in theselection of subjects. Risk-benefit analysisrequires evaluation of the scientific merit ofthe study and weighing whether the risks tothe subjects are justified by the potential find-ings of the study. Thus, subjects should not beallowed to consent to a study that is so poorlydesigned that little useful information is likelyto result or to one where the risks to the sub-jects are so great that even a study producingvaluable information is not warranted.

The environmental release experimentssuch as the Green Run at Hanford [10] areexamples of the former type of ethical prob-

12 Medicine & Global Survival 1994; Vol. 1, No. 1 Government-Sponsored Radiation Research

lems. Here the studies were not intended tostudy effects on human beings, but potential-ly thousands of people were unknowinglyexposed to radiation for the sake of experi-ments related to understanding spread offallout or interpretations of aerial intelligenceover the Soviet Union. The humans exposedwere not studied for any potential medicaleffects, violating another tenet of theNuremberg code and requiring the expensiveand difficult dose reconstruction studies cur-rently conducted by the CDC.

Vulnerable PersonsJustice requires that persons who are

intrinsically vulnerable to exploitation,unable to speak for themselves, or represen-tative of disadvantaged groups not be usedas subjects of research unless the researchaddresses a problem specific to that groupthat cannot be as easily done in a more gen-eral population. The Oak Ridge whole-bodyradiation experiments, which used enormousdoses, are probably examples of studies sopotentially dangerous that information to begained would not have warranted approvalof these studies, even if informed consent hadbeen obtained, which it had not [52,53]. Thatthe subjects were said to be terminally ill isnot a justification. In fact, by criteria drawnfrom the Nuremberg and Helsinki Codes andfurther articulated by the NationalCommission, these subjects would be consid-ered especially vulnerable to exploitationand, therefore, the ethical standards forresearch are even stricter.

By these standards, nursing home resi-dents or retarded people in institutionsshould not be subjects of research unless thestudies apply directly to their own well-beingand could not be done using other subjects.In particular, institutionalized populationsare not to be used only because it is more con-venient for the investigator. The study ofnutritional physiology done in retarded chil-dren in Massachusetts apparently violatesthis principle, but reflects widespread prac-tice among legitimate investigators of thetime who commonly used institutionalizedpopulations for their research simply becauseit was more convenient [7].

Recommendations

Government PolicyThe U.S. government must review and

correct its policies regarding: secrecy anddeclassification of research reports, ethics ofthe conduct of human experimentation, com-pensation for unethical research, guidelinesfor human experimentation in mission labo-ratories, mistrust of government, and the use

of unethically obtained data. The government's policy with regard to

these disclosures should respond to the per-vasive public fear of radiation. Policy shouldfocus on improving radiation protection pro-grams and on efforts to restore public confi-dence in the agencies responsible for radia-tion health and safety. Only then can trust inthe government's assertions of safety berestored. This restoration will requireacknowledgment of the previous policy ofsecrecy and, in some cases, frank deception,as well as clear statements from the govern-ment about how such abuses will be prevent-ed in the future.

Up till now, it has been U.S. governmentpolicy, with regard to health and radiationfrom nuclear weapons production and radia-tion exposures in general to give blanketreassurance that the health of workers and ofthe general public has been fully protectedand that there has been no risk of disease orinjury from radiation in the United States. Ithas been the policy of the DOE in recentadministrations to avoid examination ofavailable health effects data and not to allowindependent research scientists to exploreclaims of harm. Secrecy in the name ofnational security, data ownership, and sub-ject confidentiality has limited independentscientific review of government informationon radiation health effects [28].

National Review PanelPerhaps the most important recommen-

dation to be made at this time is to establish anational, impartial, and credible scientificand ethical review process for the evaluationof each of the individual cases. Such a panel,like the previous National Institute of HealthEthics Advisory Board, should be national inscope and have authority to review allresearch in which governmental agencies areinvolved in any way. There should not be aspecial body just to review radiation-relatedresearch because there are many other issuesof potential ethical concern that are hard topredict or categorize at this point. The mem-bers should include appropriate scientists,ethicists, public officials, and legal scholars. Itshould be charged to review prospectivelyselected proposed studies as well as developbroad policy regarding generally difficult orcontroversial areas of research.

The panel ought to review all presentand past government experimentation withhuman subjects to inform our future policiesregarding medical follow up and compensa-tion. The panel would also analyze publishedand unpublished research reports to establishthe purpose, experimental design, consent,and other scientific ethical and appropriate-

Government-Sponsored Radiation Research McCally/Cassel/Kimball 13

ness issues. It would not be a wise use of theNational Institutes of Health Ethics AdvisoryBoard to do the extensive retrospectivereview of the research studies being investi-gated because the NIH may have approvedstudies now being rereviewed. The panelshould have the authority to subpoena docu-ments and witnesses, and should include inits membership representatives of an affectedclass of radiation subjects.

Content and Scope of ResearchResponsibility for the conduct of new

research, specifically prospective studies ofhealth outcomes of subjects of previous gov-ernment-sponsored human experimentation,must be transferred from the sponsoringagencies [28]. The barrier of secrecy and theclaim of national security must be removedfrom documents pertaining to any and allhuman experimentation conducted by anyagency of the federal government includingthe CIA. All radiation workers and potential-ly exposed public populations should beenrolled in a registry and prospective studiesof radiation health effects be undertaken,even in those whose exposures may haveoccurred many years ago. Finally, the scopeof human experimentation to be reviewedshould not be limited to radiation researchbut include studies of chemical and biologi-cal warfare.

National Data ArchivesA single agency, such as the National

Archives and Records Administration, oughtto be required to collect and organize thedata, which now are spread among many dif-ferent government bodies, and to create a sin-gle data repository for this project. Awaitingthe creation of such a resource ought not be abarrier to some studies that could and shouldproceed with existing databases. The creationof a usable data source, open to the public aswell as to investigators, is a complex enter-prise requiring expertise in epidemiology,information systems, and strategies to protectthe confidentiality of individuals. All theseissues have been considered in some depth inthe early stages of the development of theComprehensive Epidemiologic DataResource (CEDR) [54] recommended by theSecretary's Panel for the Evaluation ofEpidemiological Research Activities(SPEERA). In 1989 SPEERA was created andcharged with evaluating the DOE's record inoccupational safety and protection of itsworkers from health hazards [55]. CEDR wasthe proposed database on the some 600,000nuclear weapons production workers sincethe inception of the nuclear weapons pro-grams [54]. Unfortunately, the CEDR project

has not been completed.

Identification of Unethical StudiesMuch of the knowledge produced by the

radiation studies at the center of this currentcontroversy has been put into use in treat-ment of cancer, in designing studies to evalu-ate long-term effects of radiation exposure, indesigning manned space travel, and in set-ting occupational safety standards. It wouldbe neither possible nor desirable to pretendthis knowledge does not exist. It is, however,important that scientists referring to suchstudies identify them as unethical studies.This way the authors do not stand to gain inprestige or reputation by the exploitation ofsubjects and, in addition, future investigatorsare reminded of the ethical necessity to pro-tect human subjects in their own work.

References1. Welsome E. The plutonium experiment.Special report. Albuquerque Tribune,November 15-17,1993; 1-48. 2. Schneider K. Secret nuclear research on peo-ple comes to light. New York Times, December17, 1993; A1. 3. Lee G. US should pay victims, O'Leary says.Washington Post, December 29, 1993;A7. 4. Chicago Tribune (Associated Press). Newpanel to review data on human radiation tests.Washington Post, January 12, 1994;4. 5. Devroy A, Lee G. US forms radiation taskforce. Washington Post, January 4, 1994;A1. 6. Mann CC. Radiation: balancing the record.Science 1994;263:470-473. 7. American nuclear guinea pigs: three decadesof radiation experiments on US citizens. Reportprepared by the Subcommittee on EnergyConservation and Power of the Committee onEnergy and Commerce, US House ofRepresentatives. November 1986. Washington,DC: US Government Printing Office; 1986. 8. Smolowe J. The widening fallout. Time,January 17, 1994;30-31. 9. Congressional Record. October 15,1971;516370-516373. Washington, DC: USGovernment Printing Office; 1971. 10. United States General Accounting Office.Nuclear health and safety: examples of postWorld War II radiation releases at US nuclearsites. Washington, DC: United States GeneralAccounting Office; November 1993. 11. Rappaport R. The great American bombmachine. New York: Dutton,1971. 12.Rosenberg H. Atomic soldiers: American vic-tims of nuclear testing. Boston: BeaconPress,1980. 13. Saffer T, Kelly O. Countdown zero: Gl vic-tims of US atomic testing. New York: Penguinbooks,1983. 14. Wasserman H, Solomon N, with Alvarez R,

14 Medicine & Global Survival 1994; Vol. 1, No. 1 Government-Sponsored Radiation Research

§

Walters E. Killing our own: the disaster ofAmerica's experience with atomic radiation.New York: Delta Books, 1982. 15. Rosenberg H. Informed consent. MotherJones, September/October 1981;31-37,44. 16. Herbert J. Reagan administration memosplayed down human experiments. AssociatedPress Wire Service. January 14, 1994. 17. Hacker B. The dragon's tail: radiation safetyin the Manhattan Project, 1942-1946. Berkeley:University of California Press,1987. 18. Hacker B. Elements of controversy: a historyof radiation safety in the nuclear test program.Unpublished manuscript. Cited in: Caufield C.Multiple exposures: chronicles of the radiationage. New York: Harper & Row, 1989:282. 19.Caufield C. Multiple exposures: chronicles ofthe radiation age. New York: Harper & Row,1989. 20. White House Executive Order, AdvisoryCommittee on Human Radiation Experiments,January 18, 1994. 21. Cushman JH Jr. Study sought on all testingin humans. New York Times, January 10,1994;A8. 22. McCally M. Radiation and health: what thefight is all about. Bulletin of the AtomicScientists September 1990;46(7):14-16. 23. Ball H. Justice downwind: America's atomictesting program in the 1950s. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press, 1986. 24. Kerber R, Till JE, Simon SL, et al. A cohortstudy of thyroid disease in relation to falloutfrom nuclear weapons testing. JAMA1993;270:2076-2082. 25. US Congress Office of TechnologyAssessment. Complex cleanup: the environ-mental legacy of nuclear weapons production.Washington, DC: US Government PrintingOffice; February 1991. 26. Stone R. Scientists study "cold war" fallout.Science 1993;(262):1968. 27. Hamilton TE, van Belle G, LoGerfo JP.Thyroid neoplasia in Marshall Islandersexposed to nuclear fallout. JAMA 1987;258:629-635. 28. Geiger HJ, Rush D, et al. Dead reckoning: acritical review of the Department of Energy'sepidemiologic research. Washington, DC:Physicians for Social Responsibility, 1992. 29. York H. The advisors: Oppenheimer, Teller,and the superbomb. San Francisco: WHFreeman Co, 1976. 30. Coldwell GC, Kelley DB, Health CW Jr.Leukemia among participants in militarymaneuvers at a nuclear bomb test: a prelimi-nary report. JAMA 1980;244:1575-1578. 31. Durbin P. Written testimony presented tothe House Subcommittee on Energy and Power,Committee on Energy and Commerce. January18, 1994. 32. McCally M. The neutron bomb. PSR

Quarterly 1990;1:5-14. 33. Young R. Acute radiation syndrome. In:Conklin JJ, Walker RI, eds. Military radiobiolo-gy. New York: Academic Press, 1987:165-190. 34. Walker Rl, Cerveny TJ, eds. Medical conse-quences of nuclear warfare. In: Zajtchuk R,Jenkins DP, Bellamy RF, Ingram VM, eds.Textbook of military medicine. II. Washington,DC: TMM Publications, Office of the SurgeonGeneral, 1989:part 1. 35. Langham WH, ed. Radiobiological factors inmanned space flight. Washington, DC: NationalAcademy of Sciences/National ResearchCouncil; 1967. Publication 1487. 36. Mettler FA, Mosely RD. The medical effectsof ionizing radiation. New York: Grune andStratton, 1985. 37. Kolatya G. Experts try to look at era in judg-ing radiation tests. New York Times, January 1,1994;A1. 38. The Nuremberg Code. Reprinted in: ReiserSJ, Dyck AJ, Curran WJ, eds. Ethics in medicine:historical perspectives and contemporary con-cerns. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1977:272-273. 39. Beecher HK. Ethics and clinical research. NEngl J Med 1966;274:1354-1360. 40.Environmental Medical Division. Principles forthe conduct of hazardous human experimenta-tion. Wright Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio: USAir Force Aerospace Medical ResearchLaboratory; 1963. USAF AMRL TDR # 63-128. 41. Schneider K. 1950 memo shows worries overhuman radiation tests. New York Times,December 28,1993;A1. 42. Lifton RJ. The Nazi doctors: medical killingand the psychology of genocide. New York:Basic Books, 1988. 43. Geiger HJ. Generations of poisons and lies.New York Times, August 5, 1990;EI9. 44. Schloendorff v Society of New YorkHospital. 211 NY 125,129-30,105 NE 92,93(1914). 45. Jonas H. Philosophical reflection on experi-menting with human subjects. In: Freund PA,ed. Experimentation with human subjects. NewYork: George Braziller, Inc, 1969:1-31. 46. World Medical Association. Declaration ofHelsinki: Recommendations Guiding MedicalDoctors in Biomedical Research InvolvingHuman Subjects. (Adopted by the 18th WorldMedical Assembly, Helsinki, Finland, 1964 andrevised by the 29th World Medical Assembly,Tokyo, Japan, 1975.) 47. Curran WJ. Current legal issues in clinicalinvestigation. In: Reiser AJ, Dyck WJ, CurranWJ, eds. Ethics in medicine. Cambridge, MA:MIT Press, 1977:293-301 48. Katz J. Ethics and clinical research revisited:a tribute to Henry Beecher. Hastings CenterReport, September/October 1993;31-39. 49. Katz J. Experimentation with human beings.

Government-Sponsored Radiation Research McCally/Cassel/Kimball 15

New York: The Free Press, 1974. 50. National Commission for the Protection ofHuman Subjects of Behavioral and BiomedicalResearch. The Belmont Report. BiomedicalEthics in Public Policy. Washington, DC: USGovernment Printing Office, 1973. OS 052-003-013-258. 51. Biomedical Ethics in US PublicPolicy. Washington, DC: Office of TechnologyAssessment, Congress of the United States;1993. US Government Printing Office, OTA-BP-BBS-105. 52. Lushbaugh CC, Comas F, Hofstra R. Clinicalstudies of radiation effects in man: a prelimi-nary report of a retrospective search for dose-relationships in the prodromal syndrome.Radiat Res 1967;4(suppl 1):398412. 53. Lushbaugh, CC. Recent progress in assess-ment of human resistance to total-body-irradia-tion. Conference Paper 671135. NationalAcademy of Science/National ResearchCouncil; 1968; Washington, DC. 54. Olshansky SJ, Williams RE. A comprehen-sive epidemiologic data resource. PSRQuarterly 1991:1:145-156. 55. (SPEERA) Secretarial Panel for theEvaluation of Epidemiological ResearchActivities of the Department of Energy. Reportto the Secretary. Washington, DC: USDepartment of Energy; March 1990.

16 Medicine & Global Survival 1994; Vol. 1, No. 1 Government-Sponsored Radiation Research

![Government-Sponsored Health Insurance in India - …documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/644241468042840697/...Government-sponsored health insurance in India [electronic resource] :](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5ea2cda800833e219d7441f5/government-sponsored-health-insurance-in-india-government-sponsored-health.jpg)