Unpacking Models of PaR Symposium - Presentation Script

-

Upload

lewis-sykes -

Category

Documents

-

view

54 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Unpacking Models of PaR Symposium - Presentation Script

-

Introduction

Thanks to Toby for the opportunity to present today - my Vivas in a three weeks so this is actually good warm-up.

Im going to present what I hope will be a critical but engaging overview of my recently submitted Practice as Research Ph.D. thesis - The Augmented Tonoscope. What an augmented tonoscope actually is should become clearer through the course of the presentation.

Im aiming to introduce three different aspects of my research: a live demo of one of my creative outputs; a general overview of my project - context, motivation, key questions, key

method etc.; and a personal approach to practice as research.

Context

Im a visual musician. Im particularly interested in investigating the relationship and interplay between music and moving image. Accordingly, my research looks for contemporary responses to questions that have occupied the minds of artists, philosophers and art historians for centuries:

What might sound look like? Are there visual equivalences to the auditory intricacies of rhythm, melody

and harmony? Is it possible to characterise a visual music that is as subtle, supple and

dynamic as auditory music? Can a combination of sound and moving image create audiovisual work that

is somehow more than the sum of its parts? By what means, methods and mechanisms might this be realised?

The term Visual Music was actually first coined by the art critic Roger Fry when he wrote about the work of Vasilly Kadinsky in 1912 - and I could spend my entire presentation defining and unpacking the term and its artistic lineage - but Im only going to offer a brief overview.

Presentation at Unpacking Models Of Practice As Research Symposium, 23rd January 2015, MIRIAD, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK. This is a script of the presentation I prepared for the Unpacking Models of Practice as Research Symposium - subsequently tidied up a little. I referred to it occasionally, but in the main I talked to an iPhoto slideshow of images, videos and bullet points which helped structure my talk.

The thumbnail guides indicate the accompanying slide - a video of which is online at: https://vimeo.com/138594500.

This PDF is embedded in the relevant post at my The Augmented Tonoscope website at: http://phd.lewissykes.info/unpacking-models-of-practice-as-research-symposium/ - which includes additional details and information about the event.

-

The International Call for the Understanding Visual Music 2013 Colloquium offers an up-to-date definition which Ill leave you to read:

The term Visual Music is a loose term that describes a wide array of creative approaches to working with sound and image. Its generally used in a field of art where the intimate relationship between sound and image is combined through a diversity of creative approaches typical of the electronic arts. It may refer to visualized music in which the visual aspect follows the sounds amplitude, spectrum, pitch, or rhythm, often in the form of light shows or computer animation. It may also refer to image sonification in which the audio is drawn in some way from the image. Sometimes visual music describes a non-hierarchical correlation between sound and image, in which both are generated from the same algorithmic process, while in other instances, they are layered without hierarchy or correlation altogether. Sound and image may be presented live, on a fixed support or as part of an interactive multimedia installation.

In fact Hexagram-Concordia was host to the Understanding Visual Music Colloquium in August 2011. I was due to present at that conference but was unable to make it at the last minute due to a family bereavement. However I did present at the Understanding Visual Music 2013 Colloquium in Buenos Aires hosted by CEIArtE (Electronic Arts Experimentation and Research Centre) of the National University of Tres de Febrero.

Id argue that Visual Music can be understood as a hybrid art form which explores blending (and lending) the characteristic qualities of the aural and the visual within an audiovisual contract - typically the abstraction, temporality and tonal harmony present within music, with the representation, spatialisation and colour harmony present within visual art.

Motivation

Ive been a musician for many years - I was partner in a small independent label for much of the 90s - Zip Dog Records; a bass player for numerous barely notable bands; and since an MA in Hypermedia Studies at the University of Westminster in 1999-2000 increasingly interested in and practising mixed-media - through a series of creative collaborations most notably with the progressive AV collective, The Sancho Plan (2005-2008). We performed live on stage using electronic drum pads to trigger not just the music but also real-time animations on the screen behind us. We achieved a modicum of success - performing at the Ars Electronica Gala Ceremonies in 2006 & 2007 and developing permanent interactive installation exhibits for their Museum of the Future.

Yet despite being proud of this work, ultimately I became dissatisfied with the audiovisual production process. First it involved a large collaborative team - musicians, sound designers, performers, character artists, stop-frame and 3D animators, system architects etc. - and I increasingly wanted more out of my practice than to contribute a discreet element to a group endeavour - I wanted to shape the work from inception to realisation. Second, the audio and visual production ran as essentially separate processes - converging at distinct stages but isolated from each other for much of the often very long time it took to produce new work. I dont think The Sancho Plan is atypical in this regard - Id argue that much contemporary audiovisualisation separates the audio and visual production and post-production for much of its development. However, I wanted to try and find a different approach - a means and a method whereby audio and visual composition could occur simultaneously.

-

My thinking was that by merging these usually separate strands into a single workflow, sounds and images could interact with, influence and shape each other from the outset and then throughout all stages of composition, arrangement and mixing - and this might produce Visual Music of a different quality.

Key Method

What I wanted to realise was a real-time, direct and more elemental connection between what was heard and what was seen - through both analogue and digital means: First, by employing Cymatics - a term coined by Swiss medical doctor turned

sonic researcher Hans Jenny whose two volumes - Cymatics: A Study of Wave Phenomena and Vibration Vol. 1 (1967) & Vol. 2 (1972) - are commonly accepted as the defining works in the field. [Jenny video] I planned to use sounds ability to induce form and flow to create essentially an analogue of sound in visual form - and to use this as the basis for a visualisation device - a contemporary analogue tonoscope akin to Jennys [studio test video];

Second, I planned for a digital counterpart to this analogue device via a virtual system - effectively an emulated tonoscope. This would use computer animations generated from virtual models - themselves derived from real-world physics and mathematical laws - which could behave like the analogue device, yet have the ability to be extended, twisted and abstracted in ways the analogue never could (because I could change the laws of physics within the system at will).

However, unlike the analogue aspect for which I had Jennys precedent I had no preconceived notion of what this emulated tonoscopes outputs might actually look like. So its emerging simulations and aesthetics developed as a direct result of undertaking the research. An obvious starting point was to model the behaviour of a drum skin - and Ive demonstrated how this was used for performance in the demo at the start of my presentation. Yet an emerging focus on movement as a key intermediary between sound and image - particularly a search for qualities similar to the harmonic motion within music but in the visual domain - led to an exploration of the legacy of pioneering, computer-aided, experimental animator John Whitney Sr. and his technique of Differential Dynamics. Whitney is considered by many to be the godfather of modern motion graphics. Beginning in the 1960s, he created a series of remarkable films of abstract animation that used computers to create a harmony - not of colour, space, or musical intervals, but of motion. He championed an approach in which animation wasnt a direct representation of music, but instead expressed a complementarity - a visual equivalence to the attractive and repulsive forces of consonant/dissonant patterns found within music.

So, as a key method and central premise for my research, I set about designing, fabricating and crafting a new, hybrid analogue/digital audiovisual instrument - The Augmented Tonoscope - arguing that it would not only be an effective method for investigating this terrain, but that the slow, step-by-step, back-to-basics approach required by this strategy - utilising DIY electronics and micro controllers, open source creative coding environments such as Processing and OpenFrameworks and contemporary fabrication facilities - would facilitate looking deeper into the simple interplay and elemental relationships between sound and image - to what might be understood as essential building blocks of a visual music.

-

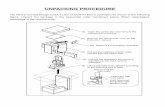

This early SketchUp mock-up illustrates how the instrument might be exhibited in a gallery setting. A physical device, drawing on the aesthetic and minimalist styling of audiophile turntables, generates a cymatic pattern induced by sound. This pattern is captured by an overhead camera and projected onto a screen. Superimposed over and augmenting this pattern is a visualisation generated from a virtual system. A controller allows the user to interact with the device and adjust its output.

Essentially half way through my PhD, and despite an emerging industrial/scientific aesthetic, the instrument featured most of the components outlined above. It had three physical devices that generated cymatic patterns induced by sound (and a fourth exploring the magnetic properties of ferrofluid). These patterns were captured by an overhead camera and displayed on a monitor - although the visualisation generated from a virtual system had not yet been integrated. Various controllers and a tailor-made musical interface allowed the user to interact with the device and adjust its output.

This progress seemed promising - I could now play musical tones; induce cymatic patterns; and capture, process and display these forms on a screen. I was yet to integrate the virtual system that would augment the physical cymatic patterns with computer animations - though I had some working prototypes - but more importantly, I needed some mechanism to compose audiovisual work by recording and editing live performance and sequencing individual parts.

However despite several months of development attempting this - at this point the project became stuck - or possibly unstuck. I was forced to reconsider my approach - and the solution was to shift perspective and to think about the instrument in a different way. Rather than try to design an overarching control system for an integrated audiovisual system I came to conceive of The Augmented Tonoscope as a modular performance system comprising of the following discrete, specialised but interconnected modules:

sound making sound analysis analogue outputs virtual systems musical interface recording and sequencing

This provided a framework for developing and refining the functionality of individual components through a more independent and parallel design process. Also describing the system through these modules allowed me to highlight specific features of the instrument, and more importantly, illustrate the way they integrated - to define the connections between them. Still, a significant repercussion of this shift in perspective was that it was unlikely that the instrument would be completed within the course of the study, and as a result, it would not be possible to produce a series of artistic works for live performance, screening and installation using it. However, it would be possible to produce a series of artistic works that reflected the development of specific modules - and this is how I reframed the research objectives.

More significantly still, through the research itself Id come to appreciate that my key research question was essentially flawed. Cymatics - while certainly offering a means to visualise sound - could not actually realise a visual equivalence to melody or harmony. The harmonic modes of a one dimensional stretched string or column of air - foundational to traditional string and woodwind instruments

-

- are the exception. Two-dimensional drum skins, vibrating plates and liquid in a bowl simply do not behave harmonically - that is the frequencies at which these systems display distinct patterns do not correlate to anything we would understand or appreciate aesthetically as a musical scale. Furthermore, my analogue tonoscope prototypes fabricated from second hand drums behaved far from ideally - they displayed a few of the theoretical modes at near to expected frequencies - but otherwise bore little relation to the ideal.

Research Methodologies & Frameworks

Despite its populist appeal, there is limited academic research into the application of Cymatics within a Visual Music context. So my investigation didnt take the traditional approach of studying research in the field in order to reveal an absence and so define a research question. Rather I trusted my implicit practitioner knowledge, gained through years of practice and curation, to identify the focus of the investigation and then steer the research through the surrounding terrain. Considering it a transdisciplinary topic meant drawing from disparate disciplines - selecting theory and practice which seemed to resonate especially with the study in order to introduce alternative perspectives, inform understanding and spark new insights. As such, the research has drawn from acoustics, sensory-centric philosophy and critical art theory - to musicology, cognitive neuroscience and computer science. It has also investigated the lineage of the practice through the ideas, approaches and techniques of inspirational artists.

This approach is informed by the concept of systems thinking proposed by Gregory Bateson - of attempting to overcome the classical problem of duality within a discourse - and his notion of an ecology of the mind - of discovering the pattern that connects within a hermeneutic system of perspectives. This suited my musicianly predisposition for pattern recognition - an ability to naturally filter out the signal from the background noise, discern emerging forms and intuit their nature. Accordingly, Ive recognised repeating motifs within the varied perspectives of the disparate sources, which through the process of the research, Ive formalised - resolved, reduced and oriented into a more concentric alignment. This process has crystallised the central argument to my thesis - of an aesthetics of vibration and a more intimate perceptual connection and harmonic complementarity between music and moving image.

I also drew from the model of research methods and critical approaches developed through PARIP (Practice as Research in Performance) - a five-year project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Board, led by Professor Baz Kershaw and the Department of Drama: Theatre, Film, Television at the University of Bristol. Robin Nelson (then at the Department of Contemporary Arts, Manchester Metropolitan University) and who sat on the PARIP Advisory Group, consequently wrote several papers and edited a book Practice as Research in the Arts: Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances which expressed, developed and refined the projects research outcomes.

PARIP proposes a dynamic model for the process of cross-referring different sources of testimony, data and evidence in a multi-vocal approach to a dialogic process. The product of Mixed-Mode Practices sits at the centre of a triangle and at one of each of the apexes sits:

Practitioner Knowledge - tacit knowledge, embodied knowledge, (phenomenological) experience, know-how The suggestion that practitioners have embodied within them, enculturated by their training and experience, the know-how to make work;

-

Critical Reflection - practitioner action research, explicit knowledge, location in a lineage A conscious strategy to reflect upon established practice as well as to bring out tacit knowledge;

Conceptual Framework - traditional theoretical knowledge, cognitive-academic knowledge Creative practice becomes innovative by being informed by theoretical perspectives, either new in themselves, or perhaps newly explored in a given medium.

Each corner of the triangle, each stage of the process of making and of research as well as the product itself, is seen as potentially knowledge-producing. Where one data-set might be insufficient to make the insight manifest, the research in its totality yields new understandings through the interplay of perspectives drawn from evidence produced in each element proposed. In sum, praxis (theory imbricated within practice) may thus better be articulated in both the product and related documentation.

In my attempt to make the communication of my research integral to my methodology, Ive implemented this model through more contemporary means - as the framework for an online research journal and its supporting documentation including a digital sketchbook, video and photography. These show how the various aspects of the study inform one another through the clearly structured categories of: complementary writing locating this praxis in a lineage of similar practices and

relating and referencing this specific inquiry to broader contemporary debate; critical reflection making embodied performer knowledge explicit

comparing and contrasting other work, finding resonance between this research and contemporary debates, offering new insights into the conceptual framework and theory implicated within the practice;

documentation of process recording evidence of ongoing practical, experimental and iterative design including tool sets, methodology and outputs, capturing moments of insight and happy accident;

artistic outputs demonstrating rigour in respect to the imaginative creation, thoughtful composition, meticulous editing and professional production of new artwork;

research frameworks describing the various research methods, techniques and structures and critical approaches and tools subscribed to, adapted or developed in order to guide and direct the research;

papers, presentations and showcases - online links to published papers, scripts to various conference and symposium presentations and documentation from opportunities to showcase work - in order to provide useful snapshots into an evolving practical experimentation and insights into areas of focus and attention reflected through current reading and thinking;

PhD milestones key proposals and reports required in the procedural pathway towards a PhD.

Specifically, it has allowed the research to share knowledge and insights with the research and wider communities through a decidedly open source modus operandi making my evolving tool set, techniques, code and software, electronic and design schematics, documentation and outputs freely available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike licence. This reflects the decidedly maker strategy of my practice - the frequently collaborative development and free exchange of information, tools and approaches characterised by a growing community of makers who bring a DIY mindset to technology.

-

CloseI think thats about it

I hope that was of interest

Thank you.

![[PPT]“Unpacking the Standards” - Griffin Middle Schoolgriffinmiddleschool.typepad.com/files/unpacking-the... · Web view“Unpacking the Standards” Last modified by install](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5b1bbcd97f8b9a28258ee047/pptunpacking-the-standards-griffin-middle-schoo-web-viewunpacking.jpg)