Unit indUstrialiZing aMeriCa - Annenberg Learner

Transcript of Unit indUstrialiZing aMeriCa - Annenberg Learner

1

Table of Contents

Unit Themes 2

Unit Content Overview 2

Video Related Materials 3

Theme One Materials 4

Theme Two Materials 14

Theme Three Materials 28

Timeline 43

Reference Materials 44

Further Reading 45

Appendix 46

session preparationRead the following material before attending the workshop. As you read the excerpts and primary sources, take note of the “Questions to Consider” as well as any questions you have. The activities in the workshop will draw on information from the readings and the video shown during the workshop.

Unit introdUCtionA new era of mass production arose in the United States because of technological innovations, a favorable patent system, new forms of factory organization, an abundant supply of natural resources, and foreign investment. The labor force came from millions of immigrants from around the world seeking a better way of life, and aided a society that needed to mass-produce consumer goods. The changes brought about by industrialization and immigration gave rise to the labor movement and the emergence of women’s organizations advocating industrial reforms.

Unit learning oBJeCtivesAfter reading the text materials, participating in the workshop activities, and watching the video, teachers will

• understand the forces that brought about unprecedented economic expansion;

• have a better understanding of the immigrants that came from Asia, Europe, and Latin America;

• learn how a favorable patent system furthered industrial expansion;

• explore why the emergence of a labor movement garnered mixed support, with some Americans calling for reform and others seeking repression;

• learn how women’s organizations emerged as an infl uential force for reform.

this Unit featUres

• Textbook excerpts (sections of U.S. history surveys, written

for introductory college courses by history professors)

• Primary sources (documents and other materials created

by the people who lived in the period) including a patent,

photographs, graphics, and text excerpts.

• A timeline at the end of the unit, which places important

events in the era of imperialism

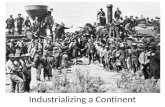

Unit 14indUstrialiZingaMeriCa

�Unit 14 Industrializing America

Theme 1: After the Civil War, the development

of improved industrial methods and

the arrival of masses of immigrants

eager for factory jobs launched a

new era of mass production in the

United States.

Theme 2: Fleeing religious and political

persecution and poor economic

conditions, millions of people began

to move around the globe, with a

high concentration coming to the

United States.

Theme 3: Industrial expansion and the

influx of new populations brought

about major changes, including

the rise of a labor movement

and the emergence of women’s

organizations as important agents

of social and political reform.

The “second industrial revolution,” which took place roughly between 1870

and 19�0, brought many changes to the United States, including the mass

production of consumer goods; large-scale migration from all parts of the

world; and patterns of social change that reshaped workplace, family,

and gender roles. Mass-produced goods rose in quantity and variety, and

became cheaper to buy. To sell these goods, entrepreneurs developed vast

communication and transportation networks that led to the creation of a

nationwide market. The government supported these developments by

making grants of land to railroad entrepreneurs and by legislating protective

tariffs, a tax on foreign, imported goods.

Often recruited by employers, a labor force eager for economic opportunity

migrated to cities from rural areas of the United States, and from Asia,

Latin America, and Europe. Millions of immigrants from China, Mexico,

Canada, southern and Eastern Europe, and Scandinavia entered all regions

of the country, with the majority settling in the Northeast. Many of these

immigrants hoped to obtain land, but—arriving penniless—often took

the first industrial jobs they could find. At first, these workers might earn

enough to support families left behind or bring the family members over

to join them. When the economy slumped, however, business owners

cut wages, increased work hours and responsibilities, or laid off workers.

In response, workers formed unions to demand improved working

conditions. Local and national strikes became increasingly frequent—even

violent. Acting as concerned consumers, many middle-class women’s

organizations pressed for reforms in labor-industrial relations.

Content overview

�Unit 14 Industrializing America

Historical PerspectivesAfter Reconstruction, mass production, mass immigration, and movements for social change converged to bring about a period of unprecedented economic expansion. Advances in mass production and mass distribution changed how people worked and lived. The nation’s patent system encouraged innovation by protecting the rights of inventors. The mass production of goods became more mechanized and efficient, output increased, and profits rose, allowing businessmen to invest and expand American industry.

Through published advertisements, American businesses recruited overseas immigrants to work in the nation’s factories, mills, farms, and railroads. Millions of immigrations from Asia, Latin America, and Europe provided the labor needed by American industry. These laborers often worked long hours at low wages and under harsh working conditions.

Eventually, workers organized to change these conditions and went on strike to win their demands. Strikes and other forms of labor protests continued throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. National reaction to labor unrest ranged from calls for reform to outright repression. Although many groups favored better treatment of workers, women’s organizations emerged as a powerful new force for labor reform: They fought for an end to child labor, the introduction of minimum wages, and improvements in health and safety conditions in factories.

Faces of AmericaCharlotte Perkins Gilman, a feminist

author; Rose Cohen, a Russian immigrant garment worker; and Ah Bing, a Chinese immigrant farmer, represented the diverse cultures and ideas that emerged during American industrialization.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, a self-educated artist and author, proposed some radical ideas about the role of women in society. Gilman believed that women should have economic and professional opportunities beyond the domestic sphere.

Rose Cohen’s memoir described the immigrant experience in Manhattan’s tenement district. Her memoir gives a compelling glimpse into the lives of European immigrants as they attempted to build a bridge from their old world origins into their new world.

Ah Bing immigrated to the United States from China and worked at the Lewelling orchard in western Oregon. During periods of anti-Chinese rioting, Ah Bing and other Chinese laborers found refuge in the Lewelling home. Chinese discrimination culminated with the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 188�, which prohibited Chinese immigration into the United States.

Hands on HistoryHow do you write a historical biography?

Rayvon Fouché, an associate professor of science and technology studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, recreates the process he used to write the book Black Inventors in the Age Segregation. Fouché researched three African American inventors by researching history at the National Archives, examining primary sources at a historic home, and interviewing the granddaughter of one of the inventors.

video related Materials

�Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe one

Theme One: After the Civil War, the development of improved industrial methods and the arrival of masses of immigrants eager for factory jobs launched a new era of mass production in the United States.

OverviewAfter Reconstruction, the nation turned its efforts toward economic recovery and expansion.

America’s abundant supply of natural resources, such as coal and oil, encouraged

investment, as did a favorable patent system that protected the rights of inventors. Much of

this investment came from abroad—from already industrialized countries such as Germany,

Great Britain, and France—whose entrepreneurs looked for new investment opportunities

in the United States. These investors put money into the work of mechanics and engineers

with the expertise to develop new, more efficient ways of mass-producing consumer goods.

New forms of factory organization, which allowed business owners to achieve economies of

scale, proliferated across the nation’s industrial areas. These economies of scale benefited

the United States by allowing business owners to specialize in the production of goods and

manufacture them in large quantities to distribute throughout the nation or export abroad.

As a result, the cost of mass-produced goods went down as their quantity and variety

(though not necessarily their quality) went up. Industrial profits rose. An expanding system

of transcontinental railroads—alongside of which a communication network of telegraph and

eventually telephone lines went up—facilitated the growth of national markets to distribute

these goods. The invention of pressure-sealed cans and refrigeration increased the availability

of foodstuffs, thereby improving the quality of life for many of the nation’s city-dwellers.

Questions to Consider1. What impact did the convergence of immigration, the influx of investment money,

and technological change have on the United States after the Civil War?

2. How did the rise in the quantity of consumer goods affect daily life? What was lost?

What was gained?

theMe one exCerpts

�Unit 14 Industrializing America

1. The Texture of Industrial Progress

When Americans went to war in 1861, agriculture was the country’s leading source

of economic growth. Forty years later, manufacturing had taken its place. During

these years, the production of manufactured goods outpaced population growth.

By 1900, three times as many goods per person existed as in 1860. Per capita

income increased by over � percent a year. But these aggregate figures disguise

the fact that many people did not win any gains at all.

As the nature of the American economy changed, big businesses became the

characteristic form of economic organization. They could raise the capital to

build huge factories, acquire expensive and efficient machinery, hire hundreds of

workers, and use the most up-to-date methods. The result was more goods at

lower prices.

New regions grew in industrial importance. From New England to the Midwest lay

the country’s industrial heartland. New England remained a center of light industry,

while the Midwest still processed natural resources. Now, however, the production

of iron, steel, and transportation equipment joined older manufacturing operations

there. In the Far West, manufacturers concentrated on processing the region’s

natural resources, but heavy industry made strides as well. In the South, the textile

industry put down roots by the 1890s.

Although many factors contributed to dramatically rising industrial productivity, the

changing character of the industrial sector explains many of the gains. Pre–Civil

War manufacturers had concentrated either on producing textiles, clothing, and

leather products or on processing agricultural and natural resources like grain,

logs, or lumber. Although these operations remained important, heavy industry

grew rapidly after the war. The manufacturing of steel, iron, and machinery meant

producers, rather than consumers, fueled economic growth.

An accelerating pace of technological change contributed to, and was shaped

by, the industrial transformation of the late nineteenth century. Technological

breakthroughs allowed more efficient production that, in turn, helped to generate

new needs and further innovation. Developments in the steel and electric

industries exemplify this interdependent process and highlight the contributions of

entrepreneurs and new ways of organizing research and innovation.

Gary B. Nash and others, eds. The American People: Creating a Nation and a Society, 6th ed. (New York: Pearson Education, 2004), 610.

6Unit 14 Industrializing America

U.s. patent for the refrigerated railroad

Question to ConsiderHow did the development of a favorable patent system stimulate

industrial and economic development?

Item 5639Andrew Chase, U.S. PAtENt for thE rEfrIGErAtEd rAIlroAd (1867).

Courtesy of the United States Patent and trademark office.

See Appendix for larger image – pg. 46

theMe one priMary soUrCe

Audience:

Purpose:

Historical Significance:

Creator:

Context:

Andrew Chase

The establishment

of a favorable patent

system contributed to

American industrial

expansion

United States Patent

and Trademark Office

To show the importance

of a patent system

in facilitating the

patent process, and

encouraging innovation

and invention

The United States established a Patent

Office, consisting of trained examiners,

to process applications for patents.

The Patent Office also gave applicants

legal recourse to contest the decisions

of the examiners by appealing to the

Supreme Court. In 1869, the United

States Patent Office charged only $��

to obtain a patent, compared to $��0

in Britain, France, and Russia; $��0

in Belgium; and $��0 in Austria. The

process of obtaining patents, the right

to legal recourse, and the low fee made

the patent system in the United States

favorable to industrial and economic

development. In this example,

Andrew Chase patented a refrigerated

railroad car that allowed the cattle

dealer Gustavus Swift to sell his beef

internationally—forever changing the

distribution of food.

7Unit 14 Industrializing America

illUstration of the BesseMer proCess

Question to ConsiderWhat impact did the Bessemer process have on industrialization in

the United States?

Item 6811Alfred r. Waud, BESSEmEr StEEl mANUfACtUrE (1876).

Courtesy of the library of Congress.

See Appendix for larger image – pg. 47

theMe one priMary soUrCe

Creator:

Context:

Audience:

Purpose:

Historical Significance:

Alfred R. Waud

Technological

innovations transformed

the production process

during industrialization.

Readers of Harper’s

Weekly

To show how the

Bessemer process

increased production

Before the Civil War, skilled workers

used a slow and costly process to

produce iron, which tended to be soft

and malleable. The development of

Henry Bessemer’s converter aided

the search for a more durable metal.

The Bessemer process transformed

iron into steel by injecting air into

it, thereby reducing the amount of

carbon. The process is credited with

launching the steel industry and

cheapening the cost of production

because it was no longer necessary

to employ highly paid skilled workers.

theMe one exCerpts

8Unit 14 Industrializing America

2. Technological Innovations

. . . Neither an inventor nor an engineer, Andrew Carnegie recognized the promise

not only of new processes but also of new ways of organizing industry. Steel

companies like Carnegie’s acquired access to raw materials and markets and

brought all stages of steel manufacturing, from smelting to rolling, into one mill.

Output soared, and prices fell. When Andrew Carnegie introduced the Bessemer

process in his plant in the mid-1870s, the price of steel plummeted from $100 a

ton to $1� a ton by 1900.

In turn, the production of a cheaper, stronger, more durable material than iron

created new goods, new demands, and new markets, and it stimulated further

technological change. Bessemer furnaces, geared toward making steel rails, did

not produce steel for building. Experimentation with the open-hearth process

that used very high temperatures resulted in steel for bridge and ship builders,

engineers, architects, and even designers of subways. Countless Americans

bought steel in more humble forms: wire, nails, bolts, needles, and screws.

New power sources facilitated American industry’s shift to mass production and

also suggest the importance of new ways of organizing research and innovation.

In 1869, about half of the nation’s industrial power came from water. The opening

of new anthracite deposits, however, cut the cost of coal, and American industry

rapidly converted to steam. By 1900, steam engines generated 80 percent of the

nation’s industrial energy supply . . .

Nash et al., 610.

9Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe one seCondary soUrCe

steel prodUCtion By the BesseMer proCess, 1869–1899

Questions to Consider1. What impact did the Bessemer process have on the production of steel?

2. What effect did the Bessemer process have on the price of steel?

Item 6642Nash et al., 612.

theMe one exCerpts

10Unit 14 Industrializing America

3. New Systems and Machines—and Their Price

During this period, more and more businesses perfected the so-called American

system of manufacturing, which dated back half a century and relied on the mass

production of interchangeable parts. Factory workers made large numbers of a

particular part, each part exactly the same size and shape. This system enabled

manufacturers to assemble products more cheaply and efficiently, to repair

products easily with new parts, and to redesign products quickly. In the early

1880s the Singer Sewing Machine Company was selling �00,000 units a year.

McCormick was producing �1,600 reapers annually. The American system also

spurred technological innovation. For example, in 188� the twine binder used in

wheat harvesting was modified with new parts for use in harvesting rice.

New technical processes also facilitated the manufacture and marketing of

foods and other consumer goods. Distributors developed pressure-sealed cans,

which enabled them to market agricultural products in far-flung parts of the

country. Innovative techniques for sheet metal stamping and electric resistance

welding transformed a variety of industries. Eager to satisfy a demand for steel

(an alloy that was stronger and harder than iron), U.S. manufacturers stepped up

production of the versatile metal. For the first time, they broke free of European

suppliers. By 1880, 90 percent of American steel was made by the Bessemer

process (named after its English inventor but developed in this country by William

Kelly), which injected air into molten iron to yield steel.

The agriculture business benefited from engineering innovations as well. These

technological advances included improvements in irrigation and new labor-saving

devices, such as the self-binding harvester (1878) and the first self-steering, self-

propelled traction engine (188�).

As farm productivity boomed, the need for hired hands evaporated. Early in the

nineteenth century, producing an acre of wheat took �6 hours of labor; in 1880,

that number dropped to �0 hours. Machines, such as the self-binding harvester,

reduced labor needs by as much as 7� percent. One agricultural worker in Ohio

observed, “Of one thing we are convinced, that while improved machinery is

gathering our large crops, making our boots and shoes, doing the work of our

carpenters, stone sawyers, and builders, thousands of able, willing men are going

from place to place seeking employment, and finding none. The question naturally

arises, is improved machinery a blessing or a curse?”

Peter h. Wood et al., eds. Created Equal: A Social and Political History of the United States (New York: Pearson Education, 2003), 542.

11Unit 14 Industrializing America

iron Chink at work in p.a.f. Cannery

Questions to Consider1. How did the Iron Chink change the production of salmon?

2. What impact did the Iron Chink have on the labor force?

Item 6522Asahel Curtis, IroN ChINk At Work IN P.A.f. CANNErY, 1905.

Courtesy of the museum of history and Industry.

See Appendix for larger image – pg. 48

theMe one priMary soUrCe

Creator:

Context:

Audience:

Purpose:

Historical Significance:

Asahel Curtis

Technological

innovations during

industrialization sped

up the processing

of canned goods

and contributed to

unemployment.

Unknown

To show how the Iron

Chink sped up the mass

production of canned

salmon and displaced

workers

In 190�, the Iron Chink changed

the production process for canned

salmon. Before the Iron Chink, Chinese

cannery workers manually butchered

and canned salmon. This machine,

however, cut the fish open, separated

the fins, and cleaned out the guts.

The Iron Chink drastically cut the

processing time, while simultaneously

taking away the jobs of Chinese

workers.

theMe one exCerpts

1�Unit 14 Industrializing America

4. Scientific Management and Mass Production

[During the early 1900s, a scientific approach to maximize worker productivity

accompanied the new methods of production.] In 1911 Frederick Winslow Taylor

wrote the Principles of Scientific Management, his guide to increased efficiency

in the nation’s industries. Taylor began his career as a laborer in the Midvale

Steel Works near Philadelphia in 1878 and rose through the ranks to become the

plant’s chief engineer. There he developed a system to improve mass production

in factories in order to make more goods more quickly. Taylor’s principles

included analysis of each job to determine the precise motions and tools needed

to maximize each worker’s productivity, detailed instructions for workers and

guidelines for their supervisors, and wage scales with incentives to motivate

workers to achieve high production goals. Over the next decades, industrial

managers all over the country drew on Taylor’s studies. Business leaders

rushed to embrace Taylor’s principles, and Taylor himself became a pioneering

management consultant.

Henry Ford was among the most successful industrialists to employ Taylor’s

techniques. . . . In 191�, Ford introduced assembly line production, a system

in which each worker performed one task repeatedly as each automobile in the

process of construction moved along a conveyor. Assembly-line manufacturing

increased production while cutting costs.

Wood et al., 653–54.

1�Unit 14 Industrializing America

ConclusionNew technologies, innovative approaches to business operations, and improved

communication and transportation networks significantly increased the amount,

variety, and affordability of consumer goods available to many Americans. The

workplace, family life, and daily life in urban centers were all profoundly changed by this

development.

Questions to Consider1. How did new technology and technical processes change the workplace during

this period?

2. How did the formation of communication and transportation networks develop

national markets?

3. What impact did these changes have on daily life?

theMe one

1�Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe one

1�

theMe two

Theme Two: Fleeing religious and political persecution and poor economic conditions, millions of people began to move about the globe, with a high concentration coming to the United States.

OverviewIndustrial expansion required an ever-growing workforce. American businesses and some

Southern planters actively recruited workers from the nation’s rural areas, as well as from

abroad through advertisements published in foreign languages around the world. Between

1870 and 19�0, approximately �6.� million migrants from Asia, Latin America, and Europe

entered all regions of the United States, with the majority settling in the Northeast and

the Midwest.

Non-native born migrants came to the United States for a variety of reasons. Some were

escaping political and religious persecution. Others, facing a declining quantity of arable

land in their homeland, were attracted its availability in America. Most immigrants left their

homelands looking for economic opportunity. The United States not only offered such

opportunity but also held out the promise of upward mobility for those locked in to the

social classes into which they had been born.

More shipping lines, faster ships, and lower costs of travel made transoceanic travel easier

than ever before. Ships brought immigrants to ports at Baltimore, Boston, New York City,

Galveston, New Orleans, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. Using transcontinental railroads

and river boats, immigrants fanned out across the country to look for jobs: the Japanese in

California’s fruit orchards, Mexicans in Colorado’s mines and beet fields, Scandinavians in

western mines, Italians in iron mining camps in Missouri, and the Irish in New York factories.

Many migrants arrived hoping to buy land, but they were often so penniless that they could

not afford to move beyond their arrival city, where they took the first job they could find.

Questions to Consider1. What drew immigrants to the United States?

2. Where did they migrate? Why?

theMe one exCerpts

1�Unit 14 Industrializing America 1�

theMe two seCondary soUrCe

Migration to the United states, 1860–1910

This map and table show the regions of the world from where immigrants to

the United States came between 1860–1910. What region of the world had the

highest number of immigrants coming to the United States? What do you think

accounts for the difference?

Item 4016Nash et al., 619.

theMe one exCerpts

16Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe two exCerpts

16

1. New Labor Supplies for a New Economy

To operate efficiently, expanding industries needed expanding supplies of

workers to grow crops, extract raw materials, and produce manufactured goods.

Many of these workers came from abroad. The year 1880 marked the leading

edge of a new wave of immigration to the United States. Over the next ten years,

�.� million newcomers entered the country, almost twice the previous decade’s

level of �.8 million.

In the mid-nineteenth century, most immigrants hailed from western Europe and

the British Isles—from Germany, Scandinavia, England, and Ireland. Between

1880 and 1890, Germans, Scandinavians, and the English kept coming, but

they were joined by numerous Italians, Russians, and Poles. In fact, these last

three groups predominated among newcomers for the next thirty-five years, their

arrival rates peaking between 1890 and 1910 . . . [In 1870, the population of the

United States was �9.8 million people; by 19�0, however, the nation’s population

had increased to 10�.7 million. During these years, one out of four people (�6.�

million) was a new immigrant.]

Many of the new European immigrants sought to escape oppressive economic

and political conditions in Europe, even as they hoped to make a new life

for themselves and their families in the United States. Russian Jews fled

discrimination and violent anti-Semitism in the form of pogroms, organized

massacres, conducted by their Christian neighbors and Russian authorities.

Southern Italians, most of whom were landless farmers, suffered from a

combination of declining agricultural prices and high birth rates. Impoverished

Poles chafed under cultural restrictions imposed by Germany and Russia.

Hungarians, Greeks, Portuguese, and Armenians, among other groups, also

participated in this great migration; members of these groups too were seeking

political freedom and economic opportunity. [People also left because there was

not enough land. The process of dividing up family plots left younger siblings

landless; others lost their lands because landowners consolidated their property

and evicted them.]

Wood et al., 548.

17Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe two priMary soUrCe

Creator:

Context:

Audience:

Purpose:

Historical Significance:

groUp of eMigrants (woMen and Children) froM eastern eUrope on deCk of the S.S. AmSterdAm

Question to ConsiderWhat do these photographs tell us about an immigrant’s experience

traveling to the United States?

Item 4345frances Benjamin Johnston, GroUP of EmIGrANtS (WomEN ANd ChIldrEN)

from EAStErN EUroPE oN dECk of thE S.S. AmSTErdAm (1899). Courtesy of the library of Congress.

See Appendix for larger image – pg. 49

Frances Benjamin

Johnston

Photographers

chronicled the migration

to the United States on

board ships.

Unknown

To show the journey to

the United States

Between 1870 and 19�0, the United

States witnessed migration on an

unprecedented scale. New shipping

lines, faster passage, and cheaper

fares brought immigrants to the United

States and other countries such as

Argentina, Australia, and Canada.

These photographs depict the large

numbers of immigrants who made

the journey, the travel conditions, and

their arrival.

18Unit 14 Industrializing America

Creator:

Context:

Audience:

Purpose:

Historical Significance:

“the new ColossUs” insCription froM the statUe of liBerty

Questions to Consider 1. Why did Emma Lazarus refer to the Statue of Liberty as

“The New Colossus”?

2. Why might some newcomers reject Lazarus’s portrayal of

immigrants? What does this representation of immigrants say

about how native-born Americans viewed them?

Not like the brazen giant of Greek famewith conquering limbs astride from land to land;Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall standa mighty woman with a torch, whose flameis the imprisoned lightning, and her nameMother of Exiles. From her beacon-handglows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes commandthe air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame,“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries shewith silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,the wretched refuse of your teeming shore,send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me,I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Emma lazarus “the New Colossus” (inscription from the Statue of liberty, New York harbor, 1886).

theMe two priMary soUrCe

Emma Lazarus

On arriving in New

York harbor, the Statue

of Liberty welcomed

immigrants.

Immigrants and visitors

to the Statue of Liberty

To raise money for

the Statue of Liberty’s

pedestal

Many immigrants left poverty and

persecution in Europe, Asia, and Latin

America, hoping to take advantage of

democratic institutions and economic

opportunity in the United States. For

those who entered the country through

New York City’s harbor after 1886,

their first glimpse of America was

often the Statue of Liberty. Despite the

welcoming tone of Emma Lazarus’s

poem, not all Americans were eager to

receive them—even though some were

fairly recent immigrants themselves.

theMe one exCerpts

19Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe two exCerpts

19

2. New Labor Supplies for a New Economy

. . . Most of the newcomers found work in the factories, mills, and sweatshops of

New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago. At the same time, large numbers of these

fresh arrivals dispersed to other areas of the country to work in a wide variety of

enterprises. Scandinavians populated the prairies of Iowa and Minnesota and the

High Plains of the Dakotas.

[Not all immigrants settled in Northern or Midwestern cities.] In the South, some

planters began to recruit immigrants—especially western Europeans of “hardy

peasant stock”—to take the place of blacks who resisted working for whites.

Nevertheless, planters’ experiments with recruiting immigrants amounted to little.

Given the opportunity, many immigrants sought to flee from the back-breaking

labor and meager wages of the cotton staple crop economy. A group of Germans

brought over to toil in the Louisiana swamps soon after the Civil War quickly

slipped away from their employers; they had agreed to the arrangement only

to gain free passage to America. Thirty Swedes who arrived in Alabama also

deserted at an opportune moment, declaring that they were not slaves. South

Carolina planters who sponsored colonies of Germans and Italians gave up in

exasperation. The few Chinese who began work in the Louisiana sugar fields

soon abandoned the plodding work of the plantations in favor of employment in

the trades and shops of New Orleans. Still, in 1890, immigrant worker enclaves

were scattered throughout the South. Irish, Polish, and Italian men were swinging

pickaxes in Florida railroad camps. Italian men, women, and children were picking

cotton on Louisiana plantations. Hungarian men were digging coal out of mines in

West Virginia.

Wood et al., 548.

3. The Heartland: Land of Newcomers

Known as the nation’s heartland, the upper Midwest carries associations of small

towns dotted with Protestant churches and inhabited by hardy Anglo-Saxon

pioneers and their descendants. But at the dawn of the twentieth century, it was

not the coastal cities, with their visible immigrant ghettos, but the settlements

in the upper Midwest, along with the lower Southwest, where the greatest

concentration of foreign-born residents lived. In the growing towns and cities of

the Midwest, newcomers from central Europe and Italy joined the earlier settlers

from Germany and Scandinavia to form farming and mining communities on the

rich soil and abundant iron deposits of the region.

theMe one exCerpts

�0Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe two exCerpts

�0

Immigrants from central and southern Europe settled in the region, which came

to be known as the “iron range.” In the 1890s, the area was sparsely settled.

As a result of the Dawes Act of 1887, which divided tribal lands into individual

parcels, much of the land originally held by Indians had been divided and sold.

Most of the Indians who were native to that region were removed to reservations.

The iron-rich areas, previously the hunting, fishing, and gathering areas of the

Native Americans, were now inhabited by lumberjacks who cut the forests. The

harsh climate, ranging from �0°F in the snowy winters to more than 110°F in the

sweltering summers, plus aggressive swarms of biting insects made it a difficult

place to settle. Nevertheless, mining companies discovered the iron deposits and

began recruiting workers, first from northern Europe and then, after 1900, from

southern and eastern Europe. By 1910, the iron range was home to �� European

immigrant groups. Gradually, these cohesive working-class communities, like

others elsewhere, developed their own brand of ethnic Americanism, complete

with elaborate Fourth of July celebrations and other festivities that expressed

both their distinctive ethnic identities and their allegiance to their adopted country.

Wood et al., 645.

4. New Labor Supplies for a New Economy

The influx of so many foreign-born workers transformed the American labor

market. Native-born Protestant men moved up the employment ladder to

become members of the white-collar (that is, professional) middle class, while

recent immigrants filled the ranks in construction and manufacturing. By

1890 Italian immigrants accounted for 90 percent of New York’s public works

employees and 99 percent of Chicago’s street construction and maintenance

crews. Women and children, both native and foreign-born, predominated in the

textile, garment-making, and food processing industries.

Specific groups of immigrants often gravitated toward particular kinds of jobs.

For example, many Poles found work in the vast steel plants of Pittsburgh,

and Russian Jews went into the garment industry and street-peddling trade

in New York City. California fruit orchards and vegetable farms employed

numerous Japanese immigrants. Cuban immigrants rolled cigars in Florida. In

Hawaii, the Chinese and Japanese labored in the sugar fields; after they had

accumulated a little money, they became rice farmers and shopkeepers. In

Boston and New York City, second-generation Irish took advantage of their

prominent place in the Democratic Party to become public school teachers,

firefighters, and police officers.

theMe one exCerpts

�1Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe two exCerpts

�1

These ethnic niches proved crucial for the well-being of many immigrant

communities. They provided newcomers with an entrée into the economy;

indeed, many men and women got their first jobs with the help of kin and other

compatriots. Niches also helped immigrants advance within an industry or

economic sector. Finally, they enriched immigrant communities by keeping profits

and wages within those communities.

The experience of Kinji Ushijima (later known as George Shima) graphically

illustrates the power of immigrant niches. Shima arrived in California in 1887

and, like many other [Asian] immigrants, he found work as a potato picker in

the San Joaquin Valley. Soon, Shima moved up to become a labor contractor,

securing Japanese laborers for the valley’s white farmers. With the money he

made, he bought 1� acres of land and began his own potato farm. Eventually he

built a large potato business by expanding his holdings, reclaiming swampland,

and investing in a fleet of boats to ship his crops up the coast to San Francisco.

Taking advantage of a Japanese niche, Shima had prospered through a

combination of good luck and hard work.

[American businesses recruited Asians to work in sugar fields in Hawaii and on

the railroads in Utah. On the Central Pacific Railroad, the Chinese accounted for

about 90 percent of the workforce. The Chinese also worked in the shoe, cigar,

and garment industries in California. By 1870, San Francisco was the ninth-

largest manufacturing city in the United States, and about �0 percent of the

workforce was Chinese. Employers had an advantage in hiring Chinese labor:

There was a dual wage system and they paid the Chinese about one-third less

than they paid white laborers.

Typically, the sons left and sent money back to their families. Even though many

were already married, employers prevented the Chinese from bringing their families

into the country; employers only wanted male laborers. Chinese men circumvented

the law by claiming they had parents who were American citizens. Some American-

born Chinese men provided documentation for numerous “paper sons” unrelated

to them, who then entered the country legally. Because record keeping was

irregular, and many birth records were lost in fires following the 1906 San Francisco

earthquake, immigration authorities often failed to discover the truth.

As more Chinese laborers replaced white laborers, there was a growing

resentment against them. Native-born or European-born workers accused Asians

of lowering wages and causing unemployment. The popular press stereotyped

and ridiculed the way they looked, dressed, and wore their hair.]

Wood et al., 548.

theMe one exCerpts

��Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe two exCerpts

��

5. The Homestead and Pullman Strikes of 1892 and 1894

[This tension] appeared most dramatically in the anti-Chinese campaign of the

1870s and 1880s as white workers in the West began to blame the Chinese for

economic hardships. The Chinese were particularly vulnerable because, unlike

European immigrants, they could not be naturalized. A meeting of San Francisco

workers in 1877 in favor of the eight-hour day exploded into a rampage against

the Chinese. In the following years, angry mobs killed Chinese workers in Tacoma,

Seattle, Denver, and Rock Springs, Wyoming. “The Chinese must go! They are

stealing our jobs!” became a rallying cry for American workers. When one Chinese

immigrant arrived in San Francisco in 1900, he reported that “some white boys

came up and starting throwing rocks” at the carriage in which he was sitting.

Hostility was also expressed at the national level with the Chinese Exclusion

Act of 188�. The law, which enjoyed support from the Knights of Labor in the

West, prohibited the immigration of both skilled and unskilled Chinese workers

for a 10-year period. It was extended in 189� and made permanent in 190�.

It paved the way for further restriction of immigration in the 19�0s. Although

both middle- and working-class Americans supported sporadic efforts to cut

off immigration, working-class antipathy exacerbated the deep divisions that

undermined worker unity.Nash et al., 642.

6. Chinese Lawsuits in California

. . . In rural California, job-hungry whites formed anti-Chinese groups such as

the American and European Labor Association, founded in Colusa County in

188�. The association also included employers who resented Chinese demands

for equal pay. (Most of these immigrants received two-thirds the wages of their

white counterparts for the same work.) Yet despite all the personal and legal

discrimination, the Chinese resisted.

Opposition to the Chinese hardened in the 1880s. In San Francisco, the Knights

of Labor and the Workingmen’s Party of California helped to engineer the passage

of the Chinese Exclusion Act, approved by Congress in 188�. This measure

denied any additional Chinese laborers entry into the country while allowing some

Chinese merchants and students to immigrate. (Put to the voters of California

in 1879, the possibility of total exclusion of Chinese had garnered 1�0,000

votes for and only 900 against.) In railroad towns and mining camps, vigilantes

looted and burned Chinese communities, in some cases murdering or expelling

theMe one exCerpts

��Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe two exCerpts

��

their inhabitants. In 188� in Rock Springs, Wyoming, white workers massacred

�8 Chinese and drove hundreds out of town in the wake of an announcement

by Union Pacific officials that the railroad would begin hiring the lower-paid

immigrants. While white women cheered from the sidelines, their husbands and

brothers burned the Chinese section of the town to the ground. Such attacks

erupted more and more frequently throughout the West in the late 1880s and into

the 1890s. White men contended that they must present a united front against

all Chinese, who, they claimed, threatened the economic well-being of white

working-class communities . . .

In other instances, local white prejudice overwhelmed even Chinese who sought

legal redress from violence and discrimination. In 1886 the Chinese living in

the Wood River mining district in southern Idaho faced down a group of whites

who had met and announced that all Chinese had three months to leave town.

Members of the Chinese community promptly hired their own lawyers and

took out an advertisement in the local paper stating their intention to hold their

ground. As a community they managed to survive. Still, their numbers dropped

precipitously throughout Idaho as whites managed to hound many of them out

of the state.Wood et al., 575.

��Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe two priMary soUrCe

Creator:

Context:

Audience:

Purpose:

Historical Significance:

soMe reasons for Chinese exClUsion

Questions to Consider1. What was the pamphlet’s argument for Chinese Exclusion?

2. How did the pamphlet present its argument?

Item 4010American federation of labor, SomE rEASoNS for ChINESE ExClUSIoN.

mEAt vS. rICE. AmErICAN mANhood AGAINSt ASIAtIC CoolIEISm. WhICh ShAll SUrvIvE? (1901). Courtesy of the Bancroft library,

the University of California—Berkeley.

“In view of the near expiration of the present law excluding Chinese laborers from coming to the United States and the recognized necessity of either reenacting the present or adopting a similar law, the American Federation of Labor has determined to present its reasons and solicit the cooperation of not only all of its affiliated organizations, but also of all citizens who may consider the preservation of American institutions and the welfare of a majority of our people of sufficient importance to assist in this work.

Samuel Gompers of the

American Federation

of Labor and Hermann

Gutstadt

Anti-Asian agitation

during the late

nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries

United States Senate

To promote a second

extension of the Chinese

Exclusion Act of 188�

In 1901, Samuel Gompers, who was

the leader of the AFL, and Hermann

Gutstadt, German-born cigarmaker

and avid anti-Chinese labor organizer

in San Francisco, favored Chinese

exclusion, arguing that Chinese

immigrants lowered the standard of

living for white workers. The pamphlet’s

aim was to persuade senators to renew

the extension of the Chinese Exclusion

Act of 188�. With its subsequent

extension in 190�, the Chinese

Exclusion Act barred all Chinese

from American citizenship through

naturalization. In order to maintain

trade relations with China, the United

States did allow entry of travelers,

merchants, diplomats, students, and

teachers. Restrictions and exclusions

on other immigrant groups followed.

��Unit 14 Industrializing America

. . . We furthermore desire to assure our readers that in maintaining our position we are not inspired by a scintilla of prejudice of any kind, but with the best interests of our country uppermost in our mind simply request fair consideration.

. . . Beginning with the most menial avocations they gradually invaded our industry they gradually invaded one industry after another until they not merely took the places of our girls as domestics and cooks, the laundry of our poorer white women, but the places of the men and boys, as boot and shoemakers, cigarmakers, bagmakers, miners, farm laborers, brickmakers, tailors, slippermakers, etc. In the ladies’ furnishing line they have absolute control, displacing hundreds of our girls, who would otherwise find profitable employment. Whatever business or trade they enter is doomed for the white laborer, as competition is surely impossible. Not that the Chinese would not rather work for high wages than low, but in order to gain control he will work so cheaply as to bar all efforts of his competitor. But not only has the workingman gained this bitter experience, but the manufacturers and merchants have equally been the sufferers. The Chinese laborer will work cheaper for a Chinese employer than he will for a white man, as has been invariably proven, and, as a rule, he boards with his Chinese employer. The Chinese merchant or manufacturer will undersell his white confrere, and if uninterrupted will finally gain possession of the entire field. Such is the history of the race wherever they have come in contact with other peoples. None can understand their silent and irresistible flow, and their millions already populate and command labor and the trade of the islands and nations of the Pacific . . .

Whereas the experience of the last thirty years in California and on the Pacific coast having proved conclusively that the presence of Chinese and their competition with free white labor is one of the greatest evils with which any country can be afflicted: Therefore be it Resolved, That we use our best efforts to get rid of this monstrous evil (which threatens, unless checked, to extend to other parts of the Union) by the dissemination of information respecting its true character, and by urging upon our Representatives in the United States Congress the absolute necessity of passing laws entirely prohibiting the immigration of Chinese into the United States.

American federation of labor, SomE rEASoNS for ChINESE ExClUSIoN. mEAt vS. rICE. AmErICAN mANhood AGAINSt ASIAtIC CoolIEISm.

WhICh ShAll SUrvIvE? (1901; reprinted as U.S. Senate document 102 in 1902; reissued in 1908 by the Asiatic Exclusion league, which identified

Samuel Gompers and hermann Gudstadt as its authors).

theMe two priMary soUrCe

�6Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe two priMary soUrCe

wells fargo & CoMpany express direCtory of Chinese BUsiness hoUses

Question to ConsiderHow did entrepreneurs conduct business with Chinese communities

in a climate of anti-Chinese sentiment?

Item 6524Wells fargo & Company, dIrECtorY of ChINESE BUSINESS hoUSES (1878).

Courtesy of Wells fargo Bank.

See Appendix for larger image – pg. 50

Creator:

Context:

Audience:

Purpose:

Historical Significance:

Wells Fargo & Company Express

Anti-Chinese hostility occurred during the 1870s and 1880s, but some companies profited from doing business with Chinese immigrants.

Chinese merchants in California, Nevada, and Oregon

To further promote the economic viability of Chinese communities by facilitating commerce with Chinese businesses on the West Coast

During the height of the anti-Chinese movement, Wells Fargo produced English-Chinese merchant directories in the 1870s, and again in 188�—the same year that the Chinese Exclusion Act restricted Chinese immigration. Chinese communities in remote towns and mining camps relied on Wells Fargo’s express service to communicate with Asian merchants and importers in cities of the West. The directories not only benefited Chinese communities, but also bridged the language barrier separating Chinese communities from English-speaking communities. At the Chicago exposition of 189�, Wells Fargo displayed an advertisement signaling its reliance on Chinese businesses: “The Company by its fair and impartial treatment of the public, has always enjoyed the special favor and patronage of the Chinese of the Pacific Coast, who have unbounded faith in its responsibility and integrity, both as an Express and a Bank.”

�7Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe two

ConclusionThroughout the late 1800s, industrialization fueled the need for more labor. Some

businesses recruited workers from abroad, arousing resentment among native-born

Americans, as well as among migrants who had come in earlier waves. As industry

boomed, it resulted in the recruitment of workers from abroad. A global movement

of people took place with millions of people migrating to the United States, Canada,

Argentina, and Australia. Although some migrants returned home, most of the new

arrivals settled in niche communities where previous immigrants from their homeland

spoke their language and shared their values.

Questions to Consider1. Why was a niche community so important to a new immigrant?

2. How did hiring Chinese workers affect relations with white workers?

�8Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe one

�8

theMe three

Theme Three: Industrial expansion and the influx of new populations brought about major changes, including the rise of a labor movement and the emergence of women’s organizations as important agents of social and political reform.

OverviewThe conditions under which industrial labor worked could be difficult. Unrestrained by

regulatory laws, employers obliged their laborers to work ten- to fifteen-hour shifts, usually six

days a week. They could fire workers who complained or refused to stay on the job, especially

in periods when demand for output was high. In bad economic times, employers cut wages

and increased the number and speed of machines workers were expected to operate. Some

machines were highly dangerous. The rate of industrial accidents rose, and workers rarely got

adequate compensation. At this time, no government assistance programs existed to protect

workers from accidents on the job or from cyclical unemployment.

Labor responded to such conditions in a variety of ways. Some tried to control the production

process by denouncing—or even injuring—workers whose output exceeded the norm. Others

formed local and national unions, which organized collective actions such as walk-outs and

strikes. Over the last three decades of the nineteenth century, unions waged thousands of

strikes. Some of these actions turned violent. The authorities often blamed “outside agitators”

espousing radical ideologies such as socialism, communism, and anarchism, for these

developments. Anarchists were especially feared, as they opposed all forms of government

authority, and sometimes incited followers to acts of terror.

The coming of the second industrial revolution changed the role of middle-class women in

American society. For the most part removed from the production process, they focused

their lives increasingly on being good consumers. But, because the goods they bought were

generally mass-produced far from their homes and under conditions that might not be healthy

or safe, many middle-class women began to work through their voluntary organizations—

church groups, clubs, and reform societies—to call for not only safer industrial products but

also improved working conditions for industrial labor. The tradition that women should be

concerned only with the private, domestic sphere became weaker as a result of their activism.

Questions to Consider1. How and why did the relationship between managers and workers change during the last

quarter of the nineteenth century?

2. How did mass production change the role of women in society?

theMe one exCerpts

�9Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe three exCerpts

�9

1. Militancy in the Factories and Mines

[During this period, workers were subject to the effects of business cycles and the hazards of the workplace. Worker’s compensation, unemployment insurance, social security, and health insurance did not exist.] Because no laws regulated private industry, employers could impose 10- to 1�-hour workdays, six days a week. (By the 1890s, bakers were working as long as 6� hours a week.) Industrial accidents were all too common, and some industries lacked safety precautions. Steelworkers labored in excessive heat, and miners and textile mill employees alike contracted respiratory diseases. With windows closed and machines speeded up, new forms of technology created new risks for workers. The Chicago meatpackers, who wielded gigantic cleavers in subfreezing lockers, and the California wheat harvesters, who operated complex mechanical binders and threshers, were among those confronting danger on the job.

Women wage-earners also faced dangerous working conditions. In 188� the Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor issued a report outlining the occupational hazards for working women in the city of Boston. In button-making establishments, female workers often got their fingers caught under punch and die machines. Employers provided a surgeon to dress an employee’s wounds the first three times she was injured; thereafter, she had to pay for her own medical care. Women operated heavy power machinery in the garment industry and exposed themselves to dangerous chemicals and food-processing materials in paper-box making, fish packing, and confectionery manufacturing.

Some women workers, especially those who monopolized certain kinds of jobs, organized and struck for higher wages. Three thousand Atlanta washerwomen launched such an effort in 1881 but failed to get their demands met. Most women found it difficult to win the respect not only of employers but also of male unionists. Leonora Barry, an organizer for the Knights of Labor, sought to change all that. Barry visited mills and factories around the country. At each stop, she highlighted women’s unique difficulties and condemned the “selfishness of their brothers in toil” who resented women’s intrusion into the workplace. Barry was reacting to men such as Edward O’Donnell, a prominent labor official who claimed that wage-earning women threatened the role of men as family breadwinners.

For both men and women workers, the influx of �.�� million new immigrants in the 1880s stiffened job competition at worksites throughout the country. To make matters worse, vast outlays of capital needed to mechanize and organize manufacturing plants placed pressure on employers to economize. Many of them did so by cutting wages. Like the family farmer who could no longer claim the status of the independent yeoman, industrial workers depended on employers and consumers for their physical well-being and very survival.

Wood et al., 589.

theMe one exCerpts

�0Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe three exCerpts

�0

2. The Family Economy

. . . Like colonial families, late-nineteenth-century working-class families operated as cooperative economic units. The unpaid domestic labor of working-class wives was critical to family survival. With husbands away for 10 to 11 hours a day, women bore the burden of child care and the domestic chores. Because working-class families could not afford labor-saving conveniences, housework was time-consuming and arduous. Without an ice box, a working-class woman spent part of each day shopping for food (more expensive in small quantities). Doing laundry entailed carrying water from outside pumps, heating it on the stove, washing the clothes, rinsing them with fresh water, and hanging them up to dry. Ironing was a hot and unpleasant job in small and stuffy quarters. Keeping an apartment or house clean when the atmosphere was grimy and unpaved roads were littered with refuse and horse dung was a challenge.

As managers of family resources, married women bore important responsibilities. What American families had once produced for themselves now had to be bought. It was up to the working-class wife to scour secondhand shops to find cheap clothes for her family. Domestic economies were vital to survival. “In summer and winter alike,” one woman explained, “I must try to buy the food that will sustain us the greatest number of meals at the lowest price.”

Women also supplemented family income by taking in work. Jewish and Italian women frequently did piecework and sewing at home. In the Northeast and the Midwest, between 10 and �0 percent of all working-class families kept boarders. Immigrant families in particular often made ends meet by taking single, young countrymen into their homes. Having boarders meant providing meals and clean laundry, juggling different work schedules, and sacrificing privacy. But the advantages of extra income far outweighed the disadvantages for many working-class families.

Black women’s working lives reflected the obstacles African Americans faced in late-nineteenth-century cities. Although only about 7 percent of married white women worked outside the home, African-American women did so both before and after marriage. In southern cities in 1880, about three-quarters of single black women and one-third of married women worked outside the home. Because industrial employers would not hire African-American women, most of them had to work as domestics or laundresses. The high percentage of married black women in the labor force reflected the marginal wages their husbands earned. But it may also be explained in part by the lesson learned during slavery that children could thrive without the constant attention of their mothers.

Nash et al., 635.

theMe one exCerpts

�1Unit 14 Industrializing America �1

theMe three seCondary soUrCe

nUMBer of woMen eMployed in seleCt indUstries, 1870–1910

The chart below shows the rise of women workers in industry. What industries

witnessed the largest increase? Why?

Item 6618Nash et al., 634.

theMe one exCerpts

��Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe three exCerpts

��

3. The Family Economy

By 1900, nearly �0 percent of American women were in the labor force. Employed

women earned far less than men. An experienced female factory worker might be

paid between $� and $6 a week, whereas an unskilled male laborer could make

about $8. Discrimination, present from women’s earliest days in the workforce,

persisted. Still, factory jobs were desirable because they often paid better than

other kinds of work open to women.

By the 1890s, new forms of employment in office work, nursing, and clerking

in department stores offered some young women . . . opportunities. In San

Francisco, the number of clerical jobs doubled between 18�� and 1880. But

most women faced limited employment options, and ethnic taboos and cultural

traditions helped shape choices. About a quarter of working women secured

factory jobs. Italian and Jewish women (whose cultural backgrounds virtually

forbade their going into domestic service) clustered in the garment industry,

and Poles and Slavs went into textiles, food processing, and meatpacking.

In some industries, like textiles and tobacco, women composed an important

segment of the workforce. But about �0 percent of them, especially those

from Irish, Scandinavian, and black families, took jobs as maids, cooks,

laundresses, and nurses.

Nash et al., 634.

��Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe three priMary soUrCe

strikes, ladies tailors, n.y., feB. 1910, piCket girls on dUty

Question to ConsiderWhat do these photographs tell us about how the strike was

organized?

Item 5975Unknown, StrIkES, lAdIES tAIlorS, N.Y., fEB. 1910, PICkEt GIrlS oN dUtY (1910).

Courtesy of the library of Congress.

See Appendix for larger image – pg. 51

Creator:

Context:

Audience:

Purpose:

Historical Significance:

Unknown

Two women garment

workers on picket line

during the “Uprising of

the �0,000”

People standing along

St. Paul Street, New

York City

To show the striking

garment workers

In 191�, garment workers in New York’s

largest clothing factory went on strike

for better working conditions. Their

demands included an eight-hour work

day, increased overtime pay, holiday

leave, and union recognition. They won

some concessions, including a fifty-

four-hour work week, time-and-a-half

for overtime, and five legal holidays

off. The general public supported this

strike largely because of publicity

surrounding the report of the New

York State Factory Investigating

Commission, which had exposed the

harsh and unsafe working conditions

in many of the state’s factories. The

commission was established after

1�6 workers, mostly young immigrant

girls, died in the 1911 Triangle Shirt

Waist Company fire in New York City.

theMe one exCerpts

��Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe three exCerpts

��

4. New Freedoms for Middle-Class Women

Job opportunities for . . . educated, middle-class women were generally limited to

the social services and teaching. Still regarded as a suitable female occupation,

teaching was a highly demanding job as urban schools expanded under the

pressure of a burgeoning population. Women teachers, frequently hired because

they accepted lower pay than men, often faced classes of �0 to �0 children in

poorly equipped rooms. In Poughkeepsie, New York, teachers earned the same

salaries as school janitors. Moving up to high-status jobs proved difficult.

After the Civil War, educational opportunities for women expanded. New

women’s colleges such as Smith, Vassar, Bryn Mawr, and Goucher offered

programs similar to those at competitive men’s colleges, while state schools in

the Midwest and the West dropped prohibitions against women. The number of

women attending college rose. In 1890, some 1� percent of all college graduates

were women; by 1900, this number had increased to nearly �0 percent.

Higher education prepared middle-class women for conventional female roles

as well as for work and public service. A few courageous graduates succeeded

in joining the professions, but they had to overcome barriers. Many medical

schools refused to accept women students. As a Harvard doctor explained in

187�, a woman’s monthly period “unfits her from taking those responsibilities

which are to control questions often of life and death.” Despite the obstacles,

�,�00 women managed to become physicians and surgeons by 1880

(constituting �.8 percent of the total). Women were less successful at breaking

into the legal world. In 1880, fewer than �0 female lawyers practiced in the

entire country, and as late as 19�0, only 1.� percent of the nation’s lawyers and

judges were women. George Washington University did not admit women to law

school because mixed classes would be an “injurious diversion of attention of

the students.”

Despite such resistance, by the early twentieth century, the number of

women professionals (including teachers) was increasing at three times the

rate for men . . .

Nash et al., 625.

theMe one exCerpts

��Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe three exCerpts

��

5. Challenges to Traditional Gender Roles

[During the latter part of the nineteenth century, American women moved

steadily into the public sphere. Working-class women were already in the public

sphere through their wage-earning activities. Middle- and upper-class women

took on increasingly important public roles through reform movements. These

movements, such as those for temperance, suffrage, and labor-industrial reform,

attracted thousands of black and white, middle- and upper-class women into

a growing involvement with the public sphere.] Identifying themselves primarily

as wives and mothers, some women entered the political realm through local

women’s clubs. They believed that personal intellectual development and group

political activity would benefit both their own families and society in general. In

the 1880s, the typical club focused on self-improvement through reading history

and literature. By the 1890s, many clubs had embraced political activism. They

lobbied local politicians for improvements in education and social welfare and

raised money for hospitals and playgrounds. The General Federation of Women’s

Clubs (GFWC), founded in 189�, united 100,000 women in �00 affiliate clubs

throughout the nation . . .

[State and local consumers’ leagues developed in the 1890s to work for decent

working conditions for laborers, and safe and reliable products for consumers.

They formed a National Consumers’ League in 1899. Under the leadership

of Florence Kelley, the League exposed the appalling working conditions in

sweatshops; and campaigned for minimum wages for women, the abolition of

child labor, and laws to guarantee the purity of food and drugs.]

Wood et al., 624.

theMe one exCerpts

�6Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe three exCerpts

�6

6. On-the-Job Protests

[As women’s reformers fought for legislation to protect children and families],

workers sought to control the pace of production. Too many goods meant an

inhuman pace of work and might result in overproduction, massive layoffs, and

a reduction in the prices paid for piecework. So an experienced worker might

whisper to a new hand, “See here, young fellow, you’re working too fast. You’ll

spoil our job for us if you don’t go slower.”

In attempting to protect themselves and the dignity of their labor, workers devised

ways of combating employer attempts to speed up the production process.

Denouncing fellow workers who refused to honor production codes as “hogs,”

“runners,” “chasers,” and “job wreckers,” they ostracized and even injured them.

As the banner of the Detroit Coopers’ Union proudly proclaimed at a parade in

1880: “Each for himself is the bosses’ plea / [but] Union for all will make you free.”

Absenteeism, drunkenness at work, and general inefficiency were other

widespread worker practices that contained elements of protest. In three

industrial firms in the late nineteenth century, one-quarter of the workers stayed

home at least one day a week. Some of these lost days were due to layoffs, but

not all. The efforts of employers to impose stiff fines on absent workers suggested

their frustration with uncooperative workers.

To a surprising extent, workers made the final protest by quitting their jobs

altogether. Most employers responded by penalizing workers who left without

giving sufficient notice—but to little avail. A Massachusetts labor study in 1878

found that although two-thirds of the workers surveyed had been in the same

occupation for more than 10 years, only 1� percent of them were in the same job.

A similar rate of turnover occurred in the industrial workforce in the early twentieth

century. Workers unmistakably and clearly voted with their feet.

Nash et al., 636.

theMe one exCerpts

�7Unit 14 Industrializing America �7

theMe three seCondary soUrCe

Labor Union MovementAmerican industrial workers began to form unions in the early 1800s. They believed they could win better wages and working conditions from business and factory owners if they made their demands as a group rather than confronting employers individually. They had a hard time establishing a labor union movement, however. Most Americans at the time valued individual enterprise. They also accepted an economic theory called “laissez-faire,” which held that government should not interfere with the workings of business. Thus, when employers and workers clashed, government was usually unwilling to help workers fight for better conditions.

By the Gilded Age, two types of unions had emerged, “craft” (or “trade”) unions and “industrial” unions. Trade unions organized workers within specific lines of skilled labor, such as carpentry, iron moulding, or shoemaking. Trade unions existed for specific industries, and were linked through multiple “locals” around the country. In the nineteenth century, only white males could belong to trade unions. “Industrial” unions offered membership to all workers, skilled or unskilled, within a particular industry. The American Railway Union, for example, was an industrial union open to every worker connected with the railroads, from track checkers to office staff to engine drivers.

Both trade unions and industrial unions belonged to national federations. In 1886, craft unions representing hundreds of different trades created the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Industrial unions were vast, and could themselves be affiliated with even larger umbrella-style confederations such as the Knights of Labor, founded in the 1870s, or the Industrial Workers of the World, founded in 190�. Both the Knights and the IWW welcomed women and African Americans as members. The AFL eventually encouraged women and minorities to form separate affiliated “locals” of their own. One such organization was the Women’s Trade Union League, founded at an AFL meeting in 190�.

In this era, workers needed permission from their employers to “organize” a union. Most businesses and industries resisted unions, since unions forced them to share control with their workers. To prevent workers from forming unions, some managers fired union organizers. Other managers forced prospective employees to sign so-called “yellow dog” contracts in which they promised not to join a union. Yet other managers accepted unions, recognizing that doing so might prevent costly strikes. Once a business accepted a union, it agreed to let the union’s elected leaders negotiate contracts on behalf of their members. This style of negotiation was known as “collective bargaining.”

Sometimes unions tried to institute “closed shops.” In a closed shop union members compelled the factory to hire only workers who would join the union. Court cases in the early twentieth century overturned union rights to closed

theMe one exCerpts

�8Unit 14 Industrializing America �8

shops, arguing that such shops violated workers’ rights to contract freely with employers. In this period, unions could be taken to court for “restraint of trade,” and, just like giant corporations, could be indicted for operating “trusts” or “unlawful combinations” that restrained trade.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, American labor unions used a number of tactics to win concessions. Among these were strikes, boycotts, demonstrations, and lawsuits. They also formed alliances with political parties and social reformers. Through these strategies, they won the right to organize in many industries and to affiliate with other unions and federations. They founded a number of powerful unions, such as the United Mine Workers (UMW) and the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU).

Using the courts, unions fought injunctions, or court orders, that prevented them from striking. Through legislation they won maximum hours and minimum wage laws, workman’s compensation and workplace safety laws, and restrictions on child labor. Through strikes won and lost, including some in which striking workers died, labor unions pushed the government to mediate or arbitrate stalled disputes. Eventually, unions and their allies compelled the major political parties and prominent politicians, especially members of the Democratic Party, to address labor concerns that minority parties from the Greenback Labor Party to the Socialist Party had been advocating since the 1870s.

Although many Americans sympathized with industrial workers, the union movement did not always enjoy widespread popular support. The public was especially suspicious of unions during national strikes and times of national crisis, such as wars and depressions, when some people feared that union agitation might lead to violent revolution. Nor did union appeals for government backing always succeed.

The government did respond positively to unions in several ways. First it established a Bureau of Labor within the Department of the Interior and, in 191�, a full Department of Labor with a Secretary of Labor in the President’s Cabinet. In 191�, Congress passed the Clayton Antitrust Act, which included a section declaring that unions could not be considered “unlawful combinations” operating in “restraint of trade,” and that strikes, boycotting, and picketing did not violate federal law. By World War I the U.S. government had abandoned “laissez-faire” policies and become more responsive to the issues that the union movement had brought to its attention.

Elisabeth I. Perry and karen manners Smith, The Gilded Age and Progressive Era: A Student Companion (oxford: oxford University Press, 2003), 190–92.

theMe three seCondary soUrCe

theMe one exCerpts

�9Unit 14 Industrializing America

theMe three exCerpts

�9

7. Militancy in the Factories and Mines

Not until 19�� would American workers have the right to organize and bargain

collectively with their employers. Until then, laborers who saw strength in

numbers and expressed an interest in a union could be summarily fired,

blacklisted (their names circulated to other employers), and harassed by private

security forces.

. . . [T]he growing diversity of the labor force made unity difficult. For example,

among the white workers of the Richmond Knights were leaders with names such

as Kaufman, Kaufeldt, Kelly, and Molloy, suggesting the ethnic variety of late-

nineteenth-century union leadership. This diversity paralleled the composition

of the general population. In 1880, between 78 and 87 percent of all workers in

San Francisco, St. Louis, Cleveland, New York, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Chicago

were either immigrants or the children of immigrants. Most hailed from England,

Germany, or Ireland, although the Chinese made up a significant part of the

laboring classes on the West Coast. By 1890 Poles and Slavs were organizing in