uir.ulster.ac.ukuir.ulster.ac.uk/34489/1/BJN Nurse mentor... · Web viewpractice change...

Click here to load reader

Transcript of uir.ulster.ac.ukuir.ulster.ac.uk/34489/1/BJN Nurse mentor... · Web viewpractice change...

Abstract

Following the introduction of a regional nurse mentor preparation programme,

research was undertaken within a Health and Social Care Trust to explore both the

trainee mentors’ and their supervisors’ perception of this new programme. A

qualitative study involving focus groups comprised of a total of 12 participants

including five trainee mentors and seven supervisors, known as experienced

mentors, who had recently completed a mentor preparation programme was

undertaken. Data were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) thematic analysis.

Three themes were identified from the data, personal investment: including the

emotional impact of mentoring, contextual perceptions: environmental factors such

as time, and intellectual facets related to personal and professional growth.

Comprehensive preparation of mentors would appear to be effective in developing

mentors with the ability to support nursing students in practice. However, further

study would be warranted to explore how to support mentors in balancing the

demands of their mentoring role with the delivery of patient care.

Keywords:

Nurse mentorship; knowledge and skills; experiential learning

Research article

Introduction

The Standards to Support Learning and Assessment in Practice (SLAiP) (Nursing

and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2008), developed as a result of research (Duffy 2003),

resulted in the recommendation for greater training and support for mentors. The

development and dissemination of these Standards assumed that they would be

applied to practice and that practice would thus progress and be enhanced.

However, the findings of Duffy (2003) and contemporary literature are replete with

the difficulties mentors face in undertaking their restructured role in complex and

1

pressurised environments (Gainsbury 2010; Jokelainen et al 2013; Black et al 2014).

This suggests that the quality of learning is heavily influenced by the quality of the

clinical experience and the culture and context in which learning occurs (Koh 2002;

Brown and McCormack 2011).

The NMC (2008) requires that all mentors who support pre-registration nursing

students must provide feedback and undertake assessment of proficiency.

Nevertheless, in contrast to the NMC stance, the literature suggests that mentors

consistently experience difficulty in meeting the demands of teaching, assessing,

supervising, supporting and guiding students in practice (Casey and Clark 2011;

Wells and McLoughlin 2014). Consequently, students may receive inconsistent and

negative practice learning experiences, resulting in their failure to achieve the

necessary competencies to practice safely at the point of registration (Castledine

2005; Andrews et al 2006). The literature also continues to report that mentors

remain reluctant to fail students with Black et al (2014 p234) claiming that ‘a new

horizon of moral courage in mentorship’ is required. Nurse leaders should therefore

develop a culture that promotes courage and integrity in mentorship so that mentors

feel able to undertake their role. They are also ideally placed to provide the support,

which new mentors require in the early stages of their role development, in order to

facilitate the application of knowledge and skills gained during the mentor

preparation into practice (Black et al 2014).

Despite challenges persisting, research since the introduction of SLAiP (NMC 2008),

suggests that mentors do benefit from the preparation, resources and support

mechanisms currently in place (Mead et al 2011). It is argued that although formal

teaching potentially increases knowledge, it is teaching integrated into the reality of

clinical practice that is most likely to enhance skill development and influence

2

practice change (Coomarasmy and Khan 2004; Hughes and Quinn 2013).

Additionally, Walsh (2010) argues that the responsibility for a good placement rests

upon the mentor. Therefore, for pre-registration nurses to achieve the knowledge

and skills they require, mentors need to balance heavy clinical workloads, which take

precedence over learning (McGowan, 2006; Evans et al 2010), with their role as

primary providers of student education in practice (Watson, 2006). Arguably what is

required is additionally support.

Taking on board the challenges outlined above, the regional programme that was

developed aimed to provide enhanced training and support for mentors and meet he

NMC requirements (Table 1). Spanning a period of three months, the new

programme incorporated both theory and experiential learning which involved an

experienced mentor supervising and supporting a student mentor. It was designed in

partnership with the regional Health and Social Care organisations and three Higher

Educational Institutes and approved by the NMC. This article considers whether

mentors are able to transfer the knowledge and skills gained from the mentor

preparation programmes to mentorship practice?

Aims:

The aims of the study were to:

1) Gain an understanding of how experienced mentors viewed the new training

in comparison to their own experience in a previous programme.

2) Gain in-depth knowledge of factors that enhanced or inhibited mentors’ ability

to meet the requirements of their role.

3) Evaluate how, from the mentors perspective, the mentor preparation

programme influenced the quality of mentorship practice.

3

Method

A qualitative study using four focus groups (FG) provided an opportunity to facilitate

reflection and debate among the participants (Table 2). This data was audio-

recorded, transcribed verbatim, anonymised and thematically analysed using the six

step approach to data analysis promoted by Braun and Clarke (2006). This approach

is non-linear and instead provides a “recursive process, where you move back and

forth as needed, throughout the phases” (Braun and Clarke 2006, p16). As the

researcher worked closely within the mentor preparation programme, reflexivity was

used (Coghlan and Brannick, 2005). To enhance the rigour and trustworthiness of

the data and ensure that the study accurately reflected the participants’ experience,

member checking of the subsequent transcription with a volunteer from each group

and discussion with an independent experienced supervisor was undertaken

(Streubert and Carpenter 2011).

Ethics

To satisfy Trust requirements, local Research Governance and Ethics Committee

approval was sought and granted prior to commencement of the study

(11/NIR02/11). In addition, permission was obtained from the ward sisters/charge

nurses to approach the mentors eligible to participate. Confidentiality was assured

and written consent obtained.

Sampling

Research inclusion criteria required participants to have undertaken a mentor

preparation programme either as a trainee mentor (TM), (n=5) or an experienced

mentor (EM), (n=7). All twelve mentors worked in the secondary care setting and

4

volunteered from fields of nursing practice (NMC 2010) that included adult, children’s

and mental health. No participants volunteered from the field of learning disability.

Findings

This research illustrates the impact that the introduction of a regional mentorship

programme, alongside the Standards to Support Learning and Assessment in

Practice (NMC 2008), had on progression of mentorship practice. Evaluation of the

data led to the identification of a number of tentative sub-themes which were refined

under four headings (Figure 1). Re-examination and member checking of the data

revealed common themes which could be grouped together under three key

headings: intellectual facets, contextual perceptions and personal investment (Figure

2).

Intellectual facets

“Intellectual facets” relates to the positive effect the new programme had on

theoretical knowledge development and the growth of self-awareness of both trainee

and experienced mentors. For example, there was an assumption made that an

experienced mentor had all the knowledge necessary to support the development of

the trainee mentor, whereas in reality experienced mentors described how they

‘were never really told how to deal with a problem student (EM, FG 2) ……. we just

winged it’ (different EM, FG 2). In contrast, mentors cited how the new programme

not only developed their appreciation of accountability but also provided guidance on

identification and management of struggling students. Those who experienced a

struggling student since completion of the programme considered they were able to

apply their new theoretical and experiential learning, as “... you’re able to justify your

5

actions more....” (EM, FG2), and “it’s very hard to tell somebody that they’re not what

they should be, so it was just making sure there was evidence for that” (TM, FG3).

All participants described the theory component of the new programme in a positive

manner, they reported ‘it’s helped me get more confidence’ and being taught new

skills helped them achieve a clearer understanding of ‘how to offer advice and

constructive criticism” (TM, FG4). Working through the required portfolio with the

trainee mentor appears to have acted as a form of reflection for the experienced

mentor. The data suggested this has resulted in raised self-awareness leading to a

more person-centred approach and change of practice: “…it did make me take a

stand back and realise... not everybody does that...” (EM, FG2).This application of

knowledge to practice and growth of self-awareness was also identified by the

experienced mentor when observing the trainee mentors after the programme in that

“she seemed to …maybe change things round when she could see people didn’t

click [with] what she said...so would be able to use different tactics” (EM, FG2).

Furthermore, there was a suggestion that role-modelling reflective behaviours

positively influenced other mentor colleagues within the practice area: “They’ve seen

him [TM] do it [reflect] and me do it so, you know, well, this would be a good idea,

and it’s just learning from other people” (EM, FG1).

Contextual perceptions

“Contextual perceptions” relates to factors within the practice setting that mentors

perceived enhanced or inhibited their ability to carry out their role (for example, time,

managerial and team support, and challenge in relation to accountability). All

mentors acknowledged an enhanced appreciation of their accountability in relation to

verifying students as safe and effective practitioners. They reported that the mentor

6

role carries much “… more responsibility now… yes, we signed our name [before]

but the ultimate responsibility wasn’t with us” (EM, FG2). Further support for Duffy’s

(2003) notion that accountability was previously perceived as not being the

responsibility of the mentors in practice was evidenced by an experienced mentor

who stated: “…it was the university, somebody else’s responsibility, never yours”

(EM, FG2). However, a developed appreciation of accountability was perceived by

one participant to have the negative effect of causing some nurses to be reluctant to

become mentors, claiming it “... makes people, I think, ‘I don’t want anything to do

with this’ ... because they don’t want to have that conversation, you know, failing

them...” (EM, FG1).

A developed appreciation of accountability appeared to be linked to a drive to fulfil

the requirements of their role more thoroughly: “People think just because... it’s a

management student… you have an easier time... it’s probably ten times harder

because you’re trying to make sure that nurse is ready ... to not just qualify but... to

practise for years” (TM, FG4). Several mentors contended that some nurse

colleagues and managers failed to recognise the responsibility and effort that is

involved in mentoring a student: “… so we’re not paid any extra for it and we rarely

get the recognition for it but we have all this big responsibility” (EM, FG1). Also, “…

our sister hasn’t been a mentor in a long time... it’s like, ‘you take extra ... patients

‘cause you’ve got the student’, whereas ... that’s not really what it’s about... you have

to teach them...” (EM, FG2).

The main concern for all participants during the programme was in relation to

securing time within the practice environment to focus on the mentorship role. Even

an experienced mentor who was also a manager “found it very difficult to let the

student have the time with their mentor ... because we’re used to having those 37.5

7

hours a week hands-on. ... in truth a lot of it was probably... done at home or after

your shift...” (EM, FG2). A trainee mentor supported this, stating: “… your first priority

is those patients, you know, then comes the student” (TM, FG4).

The level of managerial support varied but personal experience as a mentor, either

current or past, was considered a positive influence. All participants were consistent

in acknowledging the need for the practice area to be an effective learning

environment. Discussion highlighted mentorship teamwork and support within

practice - for example: “… the mentor obviously has responsibility for them... but the

team adopts the student and looks after them...” (EM, FG1).

Personal investment

“Personal investment”, recognised the emotional impact of mentorship practice,

ranging from the challenges encountered to events that acted as a source of

fulfilment. Many stressors were identified (Figure 1) but these would appear to be

balanced by the personal satisfaction of supporting the development of others.

All participants negatively described their initial impressions of what was required to

complete the programme - words such as “scary” and “daunting” were used.

However, engagement with the mentorship programme promoted the development

of new learning and transformed these views to positive affirmations such as “… it

was worth it though in the end because I did get a lot of confidence out of the

programme ...” (TM, FG4) and “It really made me feel much more at ease as a

mentor” (EM, FG2). Additionally trainee mentors identified their experienced mentor

as a positive influence and their main source of practical advice and support. Trainee

mentors articulated the significant time and effort invested by their experienced

mentors: “[discussing a struggling student] he [EM] talked it through first of all...

8

before we went and spoke to the student, you know, how I would deal with it ...it was

nice because he backed me up first of all and let me go and do it [agree an action

plan with the student]” (TM, FG4).

To manage aspects of emotional burden, resourceful ways to address the time

challenges in completing the programme portfolio were identified: “I’d stay an hour

after shift or she’d come in early for her shift and then we’d e-mail each other quite a

bit” (TM, FG3). One experienced mentor indicated an altruistic reason for the effort

involved: “…’you want to get the person through it because you need more mentors”

(EM, FG1). However, this altruism was outweighed by personal satisfaction as the

mentor clarified that “… it was really a joy to do it [sounds of agreement from others]

in many ways, even though it was extra work” (EM, FG1). Trainee mentor attributes,

such as motivation and having a desire to learn, were identified by the majority of

experienced mentors (n=4) as factors that resulted in feelings of satisfaction as “… it

was nice to see somebody progress...” (EM, FG1).

All participants described various stressors in their mentorship role in general,

including feelings of guilt at trying to balance commitments between patients,

colleagues and students. Finding sufficient time to support the nursing students was

identified as challenging for all participants, both in completing the students’

documentation and in practice learning: “what do they need that [teaching] session

for? Sure get them to go home and read up on it, and maybe they have went [sic]

home and read up on it but actually don’t understand it, so you actually need that

time to sit and go through it with them” (TM, FG4). This lack of understanding on the

part of colleagues for what the mentor role entailed also resulted in feelings of

frustration: “… sometimes it’s just: ‘well you can do more ’cause you’ve got the

student’…” (EM, FG2).

9

Conclusion.

The research findings highlighted that the introduction of a regional mentor

programme, combining experiential understanding with theory and critical analysis

(Cooper, 2011) was advantageous in developing and supporting mentors.

Transformative learning (Deleuze, 2001), where practice is modified based on a

change in perspective, incorporates theory, experience and feeling and can be

evidenced in this study through development within the three themes: intellectual

facets, contextual perceptions and personal investment.

Achieving the required elements of the programme enabled the trainee mentor and

experienced mentor to work closely together, with subsequent positive outcomes

such as increased theoretical understanding and the development of professional

confidence resulting in competency in the mentorship role (intellectual facets).

The challenges of working in pressurised ward environments concerned mentors as

they considered it resulted in inconsistent learning experiences (Castledine 2005;

Andrews et al. 2006). Mentors described feelings of guilt when balancing their

nursing workload with their mentor role. In part this feeling of guilt was aggravated by

pressure (real or perceived) from colleagues and also pressure from themselves to

complete their nursing duties within the same timescale as would be achieved

without a student. However, mentors considered that in practice areas where ‘the

team adopts the student’, both patients and students gained a better experience

(contextual perceptions).

The data suggests that leadership and a supportive culture need to be created to

ensure that this mentor programme and the experience of being a mentor are

embedded in practice environments. Study findings suggested that practice areas

10

with line managers who were themselves mentors, or who had current knowledge of

the mentor role, were deemed to be more supportive. Where line managers lacked

insight into the mentors’ role, participants reported more stressors and negative

aspects to their mentor practice, although not with their personal satisfaction in the

mentor role (personal investment). Arguably, there is a need for line managers to

actively promote team work and support mentors in the development of student

nurses’ learning in practice.

Limitations and recommendations

Due to the limited number of participants and the potential bias towards positive

thinkers, which the voluntary approach of this study employed, it is recommended

that future studies should be conducted to explore the identified issues in more

depth. This may confirm the findings of this study within different cultures and

contexts.

Recommendations

1. Consideration needs to be given to how to bring the knowledge and skills of

existing mentors up to the same level as those who have completed the

programme.

2. Practice Education Facilitators must work with line managers to support the

growth of person-centred cultures, raise awareness of the requirements of the

mentor role and explore creative ways within individual practice areas to support

the mentors’ needs.

3. Explore the issue of “reluctance to mentor” and if necessary identify strategies to

address and manage this.

11

Conflict of interest: the authors declare no conflict of interest.

References.

Andrews GJ, Brodieb DA, Andrews JP, Hillana E, Thomas BG, Wonga J, Rixon L

(2006) Professional Roles and Communications in Clinical Placements: A Qualitative

Study of Nursing Students’ Perceptions and some Models for Practice. International

Journal of Nursing Studies 43(7), 861–874

Black S, Curzio J, Terry L (2014) Failing a Student Nurse: A New Horizon of Moral

Courage. Nursing Ethics 21(2), 224-238

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative

Research in Psychology, 3 (2), 77-101.

Brown D, McCormack B (2011) Developing the practice context to enable more

effective pain management with older people: an action research approach.

Implementation Science 6:9 http://www.implementationscience.com/content/6/1/9

(accessed 10 April 2014)

Casey D, Clark L (2011) Roles and responsibilities of the student nurse mentor: an

update. British Journal of Nursing 20(15), 933-937

Castledine G (2005) NMC consultation on fitness to practice. British Journal Nursing

14(21), 1163

Coghlan D, Brannick T (2005) Doing Action Research in Your Own Organisation,

2nd edn. Sage Publications Ltd, London

12

Coomarasmy A, Khan K (2004) What is the evidence that postgraduate teaching in

evidence-based medicine changes anything? A systematic review. British Medical

Journal 329(7473), 1017-1019

Cooper L (2011) Activists within the academy: the role of prior experience in adult

learners’ acquisition of postgraduate literacies in a post-apartheid South African

university. Adult Educational Quarterly 61(1), 40-56

Deleuze G (2001) Empiricism and Subjectivity: An Essay on Hume’s Theory of

Human Nature. Columbia University Press, New York.

Duffy K (2003) Failing Students: a Qualitative Study of Factors that Influence the

Decisions Regarding Assessment of Students’ Competence in Practice. Caledonian

Nursing and Midwifery Research Centre. School of Nursing, Midwifery and

Community Health, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow

Evans K, Guile D, Harris J, Allan H (2010) Putting knowledge to work: a new

approach. Nurse Education Today 30, 245-251

Gainsbury S (2010) Mentors Passing Students Despite Doubts over Ability.

www.nursingtimes.net/whats_new_in_nursing/news_topics/health_workforce/

mentors_passing_students_despite_doubts_over_ability/5013922.article (accessed

10 April 2014)

Hughes SJ, Quinn FM (2013) Quinn’s Principles and Practice of Nurse Education,

6th edn. Cengage Learning, Hampshire

Jokelainen M, Jamookeeah D, Tossavainen K, Hannele T (2013) Finnish and British

mentors’ conceptions of facilitating nursing students’ placement learning and

professional development. Nurse Education in Practice 13(1), 61-67

13

Koh LC (2002) Practice-based teaching and nurse education. Nursing Standard

1(19), 38–42

McGowan B. (2006) Who do they think they are? Undergraduate perceptions of the

definition of supernumerary status and how it works in practice. Journal of Clinical

Nursing 15, 1099-1105

Mead D, Hopkins A, Wilson C (2011) Views of nurse mentors about their role.

Nursing Management 18(6), 18-23

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2008) Standards to Support Learning and

Assessment in Practice. NMC, London

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2010) Standards for Pre-registration Nursing

Education. NMC, London

Streubert HI, Carpenter DR (2011) Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the

Humanistic Imperative. 5th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins

Walsh D (2010) The Nurse Mentor’s Handbook, Supporting Students in Clinical

Practice. Open University Press, Berkshire

Watson R (2006) Is there a role for higher education in preparing nurses? Nurse

Education Today 26(8), 622-626

Wells L, McLoughlin M (2014) Fitness to practice and feedback to students: A

literature review. Nurse Education in Practice 14(2), 137-141

Key Points

1. The new programme, incorporating theory with experiential learning, led to

increased confidence and the transfer of knowledge and skills into practice.

14

2. Experienced mentors also identified role development which it is argued,

indicates a need for updating of the knowledge and skills for all mentors trained

previously.

3. Regardless of how they are trained, mentors continue to struggle balancing

the demands of their mentorship role with that of their nursing role.

4. Managerial support and strategic direction is essential if an effective learning

environment is to be achieved.

Table and Figures

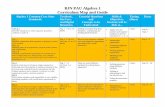

Table 1: NMC outline for Mentor Preparation Programmes (2008)

Mentor preparation programmes must: At a minimum academic level of HE Intermediate level (previously known as level

2) or SCQF Level 8. A minimum of 10 days, of which at least five days are protected learning time. Include learning in both academic and practice settings. Include relevant work-based learning, e.g. experience in mentoring a student

under the supervision of a qualified mentor, and have the opportunity to critically reflect on such an experience.

Normally, be completed within three months(NMC 2008)

Table 2: Focus group schedule

Generic questions:1. Why did you participate in the Mentor Preparation Programme?2. What benefits did you find with this programme?3. What challenges/disadvantages did you find with this programme?4. Can you identify any learning you gained through participation in this training and have you applied it to your practice?5. If you have had a struggling student since completion of the programmehow did your mentor preparation help you manage the situation?6. What changes would you implement within your area with regard to mentorship?7. If you could change one thing about the Programme what would it be and why?

TM specific questionsa. What are your views on the role of the EM?b. Can you identify any differences between how you were mentored as a student and how you now practice as a mentor?

15

EM specific questionsa. How do you compare your own programme of development as a mentor to that of the current Mentor Preparation Programme?b. What challenges did you encounter in your EM role?c. Have you had the opportunity to observe your trainee mentor mentoring since completion of the programme? If yes:d. Do you believe they continue to implement the learning and in what way?e. How does this compare to yourselves after your own mentor preparation?

Figure 1

Figure 2

16

Stumbling Blocks.

Conflict. Time. Challenge. Reluctance to mentor. Preconceived ideas. Scary.

Daunting. Failure to fail.

Personal investment

Motivation. Shared learning. Investment. Personal satisfaction. Teamwork.

Partnership. Stress.

Context

Support. Teamwork. Organised. Resourceful. Role model. Lack of

recognition.

Unexpected bonus

Reflection. Rationale. Desire to learn. Knowledge. Academic. Raised awareness of accountability. Experiential learning.

Support. Academic. Knowledge. Rationale. Teamwork. Context. Organised. Reflection.

Shared learning. Structured criticism. Challenge. Time. Conflict. Personal

satisfaction. Motivation. Reluctance to mentor. Investment. Lack of recognition.

Failure to fail. Scary. Desire to learn. Preconceived ideas. Daunting. Change to

practice.

17

Personal investment Motivation, Personal

satisfaction, Partnership, Stressors,

Desire to learn

Intellectual facets Reflective growth, Academic, Rationale

Contextual perceptions Support, Lack of

recognition, Challenge, Conflict, Reluctance to

mentor

Knowledge enhancement. Developed appreciation of accountability, Experiential

Shared learning, Constructive critique

Teamwork, Planning, Resourceful, Time, Role model

Experiential learning

![uir.ulster.ac.ukuir.ulster.ac.uk/38840/1/Manuscript PMJ-16-0295 Revise… · Web viewWord Count: Excluding quotation. s, ... [P2, AHPFG] Consequently ... A GP explained: “…you](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5aab858c7f8b9a693f8c0405/uir-pmj-16-0295-reviseweb-viewword-count-excluding-quotation-s-p2-ahpfg.jpg)