Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana;...

Transcript of Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana;...

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

1/18

Listening to the wire: criteria and techniques

for the quantitative analysis of phone intercepts

Paolo Campana &Federico Varese

Published online: 26 April 2011# Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2011

Abstract This paper focuses on phone conversations wiretapped by the police. It

discusses issues of validity and reliability of this type of data and it proposes the use

of a combination of data analysis techniques. In order to utilize wiretapped

conversations in a valid manner, individuals under surveillance must talk freely on

the phone, the coverage of the group must be reasonably wide, and a large enough

sample of conversations must be available. As for the analysis, we propose the use

of a set of techniques: content analysis, correspondence analysis, descriptive network

analysis and longitudinal stochastic actor-oriented models. Each technique highlights

a different aspect of the criminal network. Systematic analysis of phone conversationscan yield valid inferences on the nature and activities of criminal groups and enrich the

understanding of the ties within a criminal network. If followed, the procedures

discussed here should facilitate comparisons across groups.

Keywords Criminal groups . Wire tapped conversations . Content analysis . Social

network analysis

Introduction

In 2001, Coles (2001) argued that criminologists were failing to adopt social

network analysis (SNA) techniques for the study of criminal groups, and as a result

they were hindering their ability to understand underworld phenomena fully,

particularly organised crime groups. Ten years after Colesarticle, the picture seems

Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330

DOI 10.1007/s12117-011-9131-3

Authors are listed in alphabetical order.

P. Campana (*)

Extra Legal Governance Institute, Department of Sociology, University of Oxford,Manor Road Building, Manor Road, Oxford OX1 3UQ, UK

e-mail: [email protected]

F. Varese

Department of Sociology, University of Oxford, Manor Road Building, Manor Road, Oxford,

OX1 3UQ, UK

e-mail: [email protected]

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

2/18

to have changed dramatically. SNA has become increasingly popular among

scholars, generating a considerable research output (see, e.g, Natarajan 2000 and

2006; Morselli2005and2009; Bruinsma and Bernasco 2004; McNally and Alston

2006; von Lampe 2009); and it has also been adopted by a number of law

enforcement agencies across the world (such as Europol).1 SNA provides a set ofdata analysis techniques particularly apt at capturing and representing the informal

relations within illegal groups. This paper aims to draw the attention of practitioners

of SNA to a particularly rich type of data, namely phone conversations wiretapped

by the police. It discusses issues of validity and reliability of this type of data and it

proposes the use of a combination of data analysis techniquesnamely SNA,

content analysis and correspondence analysis. To our knowledge, this specific

combination of techniques has never been proposed before, nor have the limits and

potential of phone conversations wiretapped been thoroughly discussed. Most of the

research hitherto carried out relies solely on SNA techniques, disregarding thecontent of a given tie. The joint use of SNA and content analysis has been pioneered

by Mangai Natarajan (2000and2006), but has not yet received the attention that it

deserves. Our paper expands on Natarajans important contribution in two ways: (a)

it proposes the use of correspondence analysis to analyse jointly features of actors

and conversations; and (b) it addresses often neglected questions related to the

evolution of networks over time (assessed through a stochastic actor-oriented

model). An informed use of phone conversations and the combination of these

techniques allow scholars to go beyond SNA and acquire a deeper understanding of

the nature of the ties observed in the network.In the next Section, we discuss the type of data and issues of validity and

reliability. We then proceed by discussing data analysis techniques. The last Section

concludes the paper.

Data and issues of validity & reliability

A significant source of information for the researcher interested in studying criminal

groups is court records. Different kinds of court records may be examined, such as

sentences, arrest warrants, socio-economic data gathered by the police during the

investigation and wiretap records. Once the case is closed, these records are publicly

available and can be used by scholars. Nested within court records, one can find

wiretap data (Reuter 1994). When available, wiretaps are an important source of

information on the structure and activities of criminal groups and do not pose any

threat to the researcher.2

Data drawn from wiretap records have the advantage of

1 The popularity of the SNA is also reflected in the increasing amount of definitions ofOrganized Crime

that contain the term network (Varese2010: 78).2

In several jurisdictions (e.g. the United States, Canada, Germany, France, Italy, Holland and Sweden),wiretaps can be introduced as evidence in trials. Since they are to be used as evidence, the conversations

are transcribed by officers and made available to the prosecutor. On the contrary, in the UK, wiretaps

cannot be used as evidence in court, thus scholars have no access to them. Still, this information is used

extensively as part of police investigations: 2,243 warrants to intercept communications had been issued in

the UK between January and March 2006. Interestingly, police forces in the UK do not transcribe the

conversations, leading to several mistakes made by investigators, as reported by a Government review

(Reuters News Agency 20/02/2007).

14 Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

3/18

capturing conversations as they occur in their naturalsetting and may yield a fuller

picture of the group, including conversations involving lower-level and upper-level

actors. Scholars have started to utilize this source systematically (Baker and Faulkner

1993; Finckenauer and Waring 1998; Natarajan 2000 and 2006; Varese 2006;

Morselli2009; Campana2011). Yet, no in-depth examination of questions related tothe validity of these data exists. Below, we shall address these questions.

Prerequisites for quantitative analysis of phone intercepts

Given the peculiar nature of the data, a researcher is left with no conventional

statistical tests for assessing the validity of a set of wiretapped conversations. Yet,

minimizing the biases and the potential sources of error is crucial if we are to seek

meaningful results. Not all the sets of wiretapped conversations are suitable for a

quantitative and systematic analysis. Some of them are a great source of anecdotalevidence, but they may be highly misleading if analyzed in a quantitative way.

Unfortunately, the perfectset of conversations does not exist. Yet, there are ways to

assess the validity of a given set of conversations: we suggest that the following

prerequisites, if met, should guarantee a satisfactory level of validity.

A) No self-censorship Actors should talk freely on the phone about all (or most of)

the activities of a group. The use of encrypted language should not be confused with

the self-censorship about the topics discussed. In the case of criminal conversations,

we might face three different scenarios: (a) actors do not talk freely (they self-censorthemselves); (b) actors talk openly (that is to say using a non encrypted language)

and freely (touching on all or most of the activities of the group); (c) actors talk

freely but not openly. The conversations in scenario (a) are not suitable for a

quantitative analysis, and should be disregarded (the results would otherwise be

highly biased). Scenario (b) is very unlikely to happen, yet not wholly impossible.

Conversely, scenario (c) is fairly common, namely criminals use some sort of

encrypted code when touching upon all or most of the activities of the group.3

As

long as the police are able to decrypt the code, as it is often the case (Morselli2009:

43; Varese2011: ch. 4; Campana2011), then a set of conversations where a coded

language is used fulfils the no self-censorship requisite, and it can therefore be

confidently analyzed.

It is possible to check whether or not this requisite is fulfilled through two

different control strategies: an internaland an externalcontrol. An internal validity

control is based mainly on the content of a conversation. We can assume that, if the

criminals under surveillance are aware they are being listened to, they would not talk

about any serious crime they are intending to carry out. If the offenders talk

strategically on the phone, we would expect them to avoid mentioning information

that could incriminate them under the law and put them away for many years. If this

is not the case, and the protagonists do talk about incriminating matters on the

phone, such as the use of violence, torture and murders, we can be confident about

the validity of the conversation transcripts (Varese 2011: 9596). Furthermore, an

3 It can also be argued that when criminals do not talk openly, they might talk even more freely since they

do not expect the police to be able to decrypt their conversations.

Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330 1515

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

4/18

actor might hide some information to another actor, but not to all of them. Lets

assume that there are only three actors in our network (A, B and C): it might well be

the case that A hides some information to B, but he still talks openly to C. The larger

the set of conversations and actors wiretapped, the smaller is the potential bias

associated with the data. In the same vein, the broader are the categories of codingadopted the smaller is the impact of missing bits of information on the overall

results.4

An external control of self-censorship can be undertaken in two ways. First, one

can build on the goals of the agency which collects the data. The police themselves

have an incentive to validate the content of some conversations by conducting

surveillance on individuals and checking their physical and financial movements. If

two people talk on the phone about a meeting or money transfer, the police might

check this information and file a report on it. Moreover, if an actor tries to

manipulate the interlocutor giving them misleading information, the police haveagain an incentive to validate the content, highlighting the possible manipulations or

omissions.

Second, an external validation procedure can be undertaken by the researcher.

This would involve double-checking information extracted from conversation

transcripts with data collected from other court records (e.g., sentences, if available,

and arrest warrants) or through interviews with knowledgeable people (prosecutors,

judges, police investigators, individuals involved in crime). Thus, in-depth inter-

views retain a key role in this kind of quantitative research.

B) Reasonably wide group coverage All key individuals should be put under

surveillance in order to gain satisfactory coverage of the actors and the activities of a

group. If the suspects targeted for wiretapping are not representative of the group as

a whole, people who might be central will not appear so in the data simply because

their phones have not been targeted (Natarajan 2000: 293; Klerks 2001: 58).5 In an

ideal world, a researcher would aim to achieve an exhaustive group coverage, where

all the members have been put under surveillance: whilst this may be the case with

some small criminal groups, it is unlikely for very large groups. Related to this is a

second issue: actors tend to be added to the list of suspects as the investigation

proceeds, so that the group comes to look significantly different over time as a

function of police decisions to widen the net of phones being tapped.

The first concern can be addressed by an external validity control, double-

checking the information extracted from the phone wiretaps with the information

contained in other records or obtained through interviews with prosecutors and

the police. It is likely that investigators themselves have already done a check on

4 Mistaken interpretations by the police may occur. The extent to which this happens depends on the

quality of training the police forces get. In this regard, there is little that a researcher can do apart from

disregarding any set of conversations where the wiretapping activity is clearly invalidated by lack ofpreparation on the police side (this should emerge during the trial). Yet, based on our and other authors

experience (see for example Morselli 2009: 43), this is seldom the case with large and medium scale

police investigations, which are often conducted by special units. Furthermore, the impact of such

inaccurate interpretations on the overall results can be lessened by applying a coding scheme based on

broader topics.5 If there is strong evidence that the police focused on individuals suspected of particular kinds of crime

leaving out all the other members, it is better not to rely on that corpus of conversations (see also note 10).

16 Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

5/18

group coverage, adding or removing names and lines during the first months of

the investigation, until they identify a core group of actors which remains

constant till the end of the investigation. It is therefore advisable to consider only

data collected once the number of actors wiretapped is settled and constant. A

longitudinal analysis of conversation transcripts and a close analysis of the warrantsissued by prosecutors may help researchers to ascertain which individuals should be

excluded. Furthermore, investigators themselves typically offer to prosecutors

reasons as to why a given individual is tapped and for how long.

Finally, it should be noted that the criteria used by the police in deciding which

individuals should be eavesdropped have a direct impact on the type of statistical

analysis we are able to carry out. For instance, if some of the actors involved have

been directly put under surveillance and some others have not, then the likelihood of

appearing in the tapes is not the same for all the actors. In this case, it is advisable to

rely on binary measures rather than continuous ones when reconstructing thenetwork of the group (e.g. presence/absence of ties rather than the number of

contacts exchanged: see below for a broader discussion on social network analysis

techniques). Overall, the research strategy proposed cannot avoid being affected to

some extent by the goals of the law enforcement agency which collects the data, and

these goals should therefore be critically assessed by a researcher.

C) A large sample of conversations (over a reasonably long period of time) Due to

several statistical constraints, it is important to rely on a fairly large dataset of

conversations. In addition, if one plans to undertake a longitudinal analysis, it isessential to rely on a dataset where the conversations have been wiretapped for a

reasonably long period of time. The length of such period cannot be predetermined,

since it is highly dependent on the dynamic of the group over time, the specific

research questions we are to answer, and the number of conversations per day that

have been wiretapped. In our previous works, we have relied on conversations which

have been wiretapped over a period of ten and seven months respectively (Varese

2006and2011; Campana2011).

Furthermore, extensive listening may reduce the risk of selective coverage and

reveal a more accurate picture of the relationships between the actors. By large

dataset, we mean at least several hundred conversations: a large set will give the

researcher the opportunity to apply more sophisticated data analysis techniques than

simple frequency distribution.6 A set with a few dozen conversations focused on a

single activity and wiretapped for a short period of time is not worth analysing, and

could lead to unreliable and invalid results.7

The coding procedure we discuss below is indeed time consuming, and the

amount of conversations wiretapped over a long period of time may well reach a

6

It is difficult to determine a minimum threshold that has to be generally met, since this threshold is notonly a function of the data analysis techniques to be used, but also of the number of network nodes, the

duration of the intercept operation and the coding procedure.7 It is not uncommon to find un-usable set of conversations in court archives. TM ( 1994) is such an

example. The investigation focused on an Italian mafia group linked with an `Ndrangheta family who run

various types of businesses in a small town near Milan. The conversations wiretapped were less than 30

and focused only on drug dealing, and only a few actors were put under phone surveillance. A quantitative

analysis of the conversations would have led to a biased picture of the group.

Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330 1717

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

6/18

level that a single researcher or even a small team of researchers find it difficult to

handle. We believe that, instead of reducing the period of observation or the number

of actors considered, it is more fruitful to extract a simple (or systematic) random

sample from the whole set of conversations. If built in this way, the new subset will

retain the same characteristics of the bigger one, but it will result in being mucheasier to code and analyze.

The three criteria listed above represent the main requisites of validity that wiretap

evidence must satisfy. If met, they should help the researcher minimize biases and

potential sources of error. Undertaking a quantitative analysis on conversations which

do not meet these prerequisites may lead to unreliable results. These prerequisites are yet

not sufficient. At least three more issuessampling, the boundaries of the group, and

the link between talk and actionalso need to be addressed.

Samples, boundaries and behaviour

A corpus of conversations wiretapped by the police is asampleof all the conversations

that have occurred among the members of a criminal group. It is indeed quite unusual

for a researcher to have access to the universe of conversations (criminal and non-

criminal), even if they are limited to a specific medium (e.g., the phone). Even if the

universe were available, it is not obvious that it would be useful: the number of

conversations to be analyzed would massively increase; most of them would not

concern any criminal activities; the amount of time and money requested for theanalysis would increase as well. Most crucially, the purpose of the researcher is not to

estimate the ratio of ordinary conversations to criminal ones (on this, Morselli 2009).

The sample of conversations can be seen as a special kind of purposive sample,

where the purposive criterion is as follows: in order to be included in the sample (and

therefore to be transcribed in police investigation reports), a conversation must pertain

generally speaking to a criminal activity. As a general rule, this is the criterion

followed by the police during the investigation and it can be accepted by an academic

researcher without any major concern.8 It is much more likely that a trained police

officer is able to understand the criminal nature of superficially innocent remarks than

a researcher. As we said above, the police in any case would want to cast a wide net

and include more conversations than the ones that will eventually be used by a

prosecutor to build a case in court. Such a purposive criterion does not pose major

threats to validity as long as the police define criminal activity in a broad sense.

Figure 1 presents pictorially the universe of all conversations and their subsets.

The broader set is labelled A and displayed with a dashed line: it is the universe and

contains all the conversations that have occurred in everyday life using every kind of

media (phone conversations, face-to-face conversations, etc.). The universe is not

8 Investigators selectively transcribe only the conversations that are related to a criminal activity, and

therefore the only network that we are able to reconstruct is the criminal one. Yet criminals as all the

other social actors may be part of a number of different networks at the same time, and some of these

networks may also be particularly helpful in understanding the structure and evolution of the criminal one.

Whilst some extra information may be collected from other sources and still integrated into the analysis, it

is true that our purposive criterium does not allow us to reconstruct any other network but the criminal

one.

18 Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

7/18

available to researchers. A smaller subset of conversations is B, which contains all

the phone conversations that have taken place. These conversations may have been

listened to by the police, but they are usually not transcribed or included in court

records, and thus are not available to any researcher (mainly for privacy reasons; US

legislation does not allow officers to listen to B). As we have discussed before, the

police focus on conversations concerning criminal behaviour. Therefore, we may

have two more subsets of

criminality-related

conversations: a subset containing allconversations that occurred (labelled Cr) and a subset containing conversations

transcribed by the police and included in a court file (Cp). In an ideal world, Cpand

Crare perfectly overlapping, but in effect we may notice a gap and face two types of

errors: Type I and Type II. A Type I error occurs when a conversation concerning a

criminal activity is not transcribed by the police and thus not included in a court file

due to a misinterpretation of the content, an oversight of the investigator or the

technical failure of a wiretapping device. A Type II error occurs when a conversation

not concerning a criminal activity is wrongly understood and added to a court file. A

reliable corpus of conversations should minimize bias arising from such errors.

During the coding process, a researcher is able to remove any Type II error, but she

can do little about Type I errors. Moreover, it is impossible to quantify Type I errors

since the boundaries of B are unknown, and a researcher can assess the soundness of

a corpus of conversations only in a circumstantial way.

Finally, and depending on the legislation of a given country, there may be a subset

D which contains only the conversations included in the sentence issued by the

court. This set is usually very small and highly biased, and does not make a sound

basis for statistical analysis.

From content to behaviour

Conversations are texts. To what extent can they be considered as a proxy for the

actors behaviour (real or potential)? Criminal conversations about a given plan are

unlikely to be just frivolous chat. If the actors become involved in a given venture,

then the conversation about it refers to actual behaviour. If, on the contrary, the

A

B

Cr Cp

Type I Error Type II Error

Crint Cp

D

Fig. 1 Conversations as a sample

Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330 1919

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

8/18

actors restrict themselves to hypothesizing about a given plan, then their talk refers

to only potential behaviour, but still behaviour. We assume that talking with business

partners about a possible project is at least a sign of potential behaviour. Such

conversations among criminals are arguably more credible as a proxy for behaviour

than if the same conversations had taken place between academics or film buffs.Schlegel (1984: 107) maintains that conversations among criminals often

involve lies, boasts and exaggerations which may not reflect the true nature of

crime (on the same vein, see also Smith 1975: 297). To some extent, this can be

true also of data extracted through a standard questionnaire. The advantage of this

kind of data is that outright lies can be exposed by reference to other data collected

by the police, thus producing a measure of construct validity not available to most

researchers interviewing subjects through a standard questionnaire. Not only the

police validate the content of some conversations by tailing individuals and checking

their physical and financial movements; the speakers themselves would want todouble-check whether the information conveyed by fellow conspirators is accurate.

If a large enough sample of conversations is available, we would be able to see

whether some lies are eventually exposed. A criminal group in which everybody

constantly tells only lies to anybody else is simply doomed to fail from the start.

Next to outright lies, members of the groups might have an interest in omitting to

report, say, the value of a heist, to the boss. However, discussion of the robbery

would be recorded in conversations between other members of the groups.

As with any standard questionnaire, there still will be a degree of misrepresen-

tation of facts in wiretaps as well. Luckily, not all the lies have an impact on theresults of the analysis. For instance, lets assume that a member of the group gives to

the boss some wrong information about his actual behaviour while reporting about a

given task he was entrusted with. Lies and exaggerations, in this case, do not have an

impact on the coding, since the task (e.g. planning a robbery) is nevertheless

mentioned. As a more general rule, the broader the topics coded, the smaller the

impact of lies and exaggerations on the results. And the wider the set of

conversations and actors wiretapped, the smaller the risk of ending up with

misleading interpretations.

The boundaries of the network

Another threat to the validity of the data is a general issue often raised in the study of

social networks, namely, that we cannot be sure where the boundary of the network

lies (Lauman et al.1983; Scott2000: 5362; Klerks2001: 58). A pragmatic decision

is to accept that the external boundaries of the network lie where the police file

ends.9

This assumption is reasonable if (and only if) the previous requisites have

been satisfied, namely that all the key actors are wiretapped and the coverage of the

group is satisfactory.

9 It should be borne in mind that a criminal group may well be part of a bigger network of lawbreakers

related to a specific criminal industry, e.g. drug trafficking, and that members of the criminal group may be

in contact with other criminals active in the same sector. Only a substantive criterion, based for instance

on the content of wiretapped conversations or other police/court files, may help the researcher to establish

the boundaries of the criminal group under scrutiny at a specific point in time, and assess whether the

boundaries identified by the police can be accepted without major concerns.

20 Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

9/18

It should be noted that the boundaries of the overall network and those of the

criminal group do not necessarily coincide; that is to say, the network of the hard-

coremembers may well be smaller than the whole network. For instance, if we take a

network of contacts among the members of a given Mafia-group over a certain period

of time, this will include not only the bona fide Mafiosi, but also customers, potentialvictims, and fixers, among other actors. The ability to generate such a comprehensive

picture is certainly a strength of the data collection strategy that we propose to adopt;

yet, the bigger network and the sub network of bona fide Mafiosi (members) are

analytically different, and should be analyzed and interpreted accordingly (e.g., if we

are to assess whether a Mafia group is hierarchical or flat based on the informal net of

contacts, it can be argued that the analysis should be restricted to the sole members

sub network). Notwithstanding its analytical relevance, this crucial aspect of criminal

networks is hardly recognized in the literature. In order to establish where the

boundaries of the group liewe might call them internal boundaries, a researchermay turn to a substantive criterion based on a closer analysis of the content of

wiretapped conversations or other police files (see the discussion ofContent analysis

below). In conclusion, we are faced with what we might call the double-problem of

external and internal boundaries: the first issue may be solved in a pragmatic way,

while the latter requires a substantive criterion to establish the boundary (for an

example related to the Camorra case, see Campana2011).

The data analysis techniques

To exploit fully the information contained by phone conversations, we propose to

use four different techniques: content analysis, correspondence analysis, network

analysis and stochastic models for longitudinal network data. Each technique allows

us to explore a different facet of a criminal group, but it is theirjoint applicationthat

offers the fullest picture of the phenomenon. Below we discuss how each technique

relates to the type of analysis we propose scholars should undertake.

Content analysis

Content analysis is a set of techniques that aims to codify who says what to whom

systematically (Krippendorff2004; Roberts1997; Weber1990). According to Holsti

(1969: 14) content analysis is any technique for making inferences by objectively

and systematically identifying specified characteristics of messages. Thus, we

suggest undertaking content analysis of wiretapped conversations as the first step of

our approach. Systematic content analysis allows a researcher to move from texts,

processed in order to remove any repeated conversation, to a data matrix. This step

enables a researcher to apply standard statistical techniques to the analysis of

criminal groups (e.g. frequencies, crosstabs, correlations, and the like depending on

the specific research questions she is to answer). As it shall be clear later, processing

the data in a quantitative way allows a researcher to work out, for instance, how

many times a given actor has talked about a single topic, and compare this frequency

with those calculated for the other topics discussed by the same actor. In addition,

the same frequency can be compared with those calculated for all the other actors.

Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330 2121

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

10/18

Longitudinal analysis can also be carried out, e.g. with the aim to assess how the

frequency of a topic changes over time and whether a pattern of variations among

topics emerges. Quantitative analysis can help confirming anecdotal evidence

contained in a conversation.

Several procedures have been suggested for coding textual data in a reliable way(Roberts1997), depending greatly on the kind of text involved (speeches, newspaper

articles, conversations, etc.) and the aims of a given research project.

In order to code the data contained in the conversations, we suggest conducting a

thematic content analysis where the basic recording unit is a thematic unit (or,

simply, theme), defined as one or more assertions about a given subject matter

(Holsti1969). If this procedure is adopted, it follows thatsegments of conversation

where a given theme is discussed are coded. A segment of conversation is a

fragment of a conversation that has a meaningful beginning and end. As both

Berelson (1952) and Holsti (1969) point out, the theme can be considered as one ofthe most useful units of content analysis, notwithstanding two major drawbacks: (i)

thematic content analysis can be more time-consuming than other approaches; (ii)

the boundaries of the theme are not as easily identified as those of word, paragraph

or item(Holsti1969: 116), therefore this requires the employment of highly trained

coders (see below).

Coding thematic units can be a bottom-up or a top-down procedure. The starting

point of the bottom-up approach is each single conversation rather than a pre-conceived

grid of themes. For each conversation, the coder identifies the various themes discussed

by the actors. The top-down approach requires that every single conversation orsegment of conversation is coded by applying categories strictly derived from a pre-

defined set of themes. The latter approach makes it easier to undertake comparisons

across crime groups. Yet, it would be wrong to see the two approaches as mutually

exclusive. Themes identified through a bottom-up procedure can be merged with those

identified with a top-down one, thereby increasing reliability.10

Since more than one theme may be discussed per conversation, the researcher can

choose to assign a main theme or general category to each conversation.11

The

consequence of such a choice is that some information is lost, buton the plus

sideit might be easier to manipulate the data. Also, one has to decide how to code

a conversation that contains more than one theme. Arguably, the best way is to

choose the theme about which the highest number of words is spoken.12

10 As Berelson (1952: 173) points out, there could be an underestimation of reliability when the latter

arises from the measurement of reliability on detailed categories which are later subsumed into more

general categories.11 If one does choose this path, the unit of analysis becomes the single conversation, which would be akin

an item in the Berelson (1952) and Holsti (1969) classification of units. The use of different units of

analysis within the same study is recognized also by Berelson (1952), when he stressed that there is noreason [] why a particular study must use only one of the possible units of content analysis. The choice

of the appropriate unit depends upon the problem and the content under investigation, and this may

necessitate the use of different units within the same study (1952: 143).12 It may be the case that a theme is nested into deceptive preliminaries and digressions, making difficult

to quantify the correct number of words. Also for this reason, it is not possible to undertake an automatic

coding procedure. Thus, the manual coder must be highly trained in order to deal with such coding

problems.

22 Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

11/18

Given the nature of the data and research questions, we propose to undertake a

manual (not automatic) coding process. Analysis of wiretapped conversations cannot

be automatised for at least two reasons:

(a) Themes do not have a fixed length, nor can their length be predefined in an

automatic way. Rather, themes are discussed within segments of a conversation and

they are completely different from words or predefined strings between punctuation

marks or paragraphs (which a computer can adequately identify) (Holsti 1969).

(b) Actors often use cryptic, ambiguous, or slang language, too complex to be

decoded in an automatic way. Moreover, in order to properly codify the theme

of a given conversation, the coder might need to keep in mind topics discussed

in previous conversations. Software able to perform this process in a

completely automatic way does not exist.

The attention of trained human coders is therefore essential for identifying andquantifying the themes of each conversation. Moreover, a pilot test for inter-coder

reliability needs to be taken before the coding process can begin.13 Objectivity is

maintained through rigorous training and supervising of coders. Once the content

analysis is concluded, we can construct a data matrix that contains, on the rows, the

conversations, and on the columns their attributes: for example, the date and time of

the call, the identity of both caller and receiver, the number of words exchanged and

the countries of origin of both speakers as well as the themes discussed. Also, an

overall theme can be assigned to each conversation. The data can then be explored by

using several descriptive statistical techniques, such as frequencies, measures ofcentral tendency, crosstabs, and correlations. The limitation of such an analysis is that

it will be based on data derived from conversations only. In other words, attributes of

actors derived from other sources cannot be combined with data on the conversations

in order to find out who talks most about a given theme. In order to undertake such an

analysis, we turn to techniques that allow us to represent formally the two sets of data.

Correspondence analysis

Various methods for representing categorical variables in one geometrical space have

been used by scholars, including multidimensional scaling, correspondence analysis,

dual lattice analysis and other forms of dimensional representations (Torgerson 1952;

Mohr and Duquenne1997; Mohr1998; Harcourt2002; Pattison and Breiger2002).

Such methods allow us to display a synthetic representation of information contained

in the conversations with information about the actors in the same geometrical space.

Correspondence analysis is a statistical tool able to detect patterns of associations

amongst two or more variables (Greenacre 1984). Simple correspondence analysis

deals with a two-variable matrix, while multiple correspondence analysis investigates

associations between k-variables (k> 2).14 As Greenacre (1984: 54) points out,

13 For an introduction to reliability coefficients see Krippendorff (2004, ch. 11).14 To be more precise, correspondence analysis is a family of techniques based on the singular value

decomposition (SVD) algorithm. Simple correspondence analysis (SCA), multiple correspondence analysis

(MCA) and Homogeneity analysis (HOMALS) differ in respect to the type of input matrix: SCA uses a simple

bivariate crosstab, MCA a Burt matrix containing a set of bivariate crosstabs while HOMALS is based on an

Objects-by-Variables matrix (where the variables are dummy variables derived from K-polytomies).

Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330 2323

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

12/18

correspondence analysis is a technique for displaying the rows and columns of a data

matrix [] as points in dual low-dimensional vector space, usually a 2-dimensional

Euclidean space. Despite a fairly long history dating back to the 1930s (Richardson

and Kuder1933; Hirschfeld1935; Horst1935), correspondence analysis has been, as

Hill put it, a ratherneglectedmultivariate method, especially in the English-speakingworld (Hill1974). The French school rediscovered it in the early 1960s with the works

of Benzcri and his associates (see Benzcri 1973).

Data about the actors involved in the study can be extracted from police reports or

other court files. The main added value of correspondence analysis is the opportunity

to analyze data extracted from two different types of data sets, from the conversations

and from other sources containing additional information on the actors: it is thus

possible to match the content of each conversation with information about the actors

involved, obtaining a more comprehensive and detailed picture of a criminal group.

Correspondence analysis proceeds by calculating the marginal proportions for the setof categories of each variable (profiles) and, in order to mitigate the role played by the

components with higher frequency, it weights the distance between two points by the

inverse of the respective masses. This is a typical chi-square distance, and can be seen

as an example of weighted Euclidean distance (Greenacre 1984: 31).15 Correspon-

dence Analysis offers a key insight into the internal division of labour on the basis of

the variables that one is able to code (e.g., nationality, gender, place of residence,

place of birth, criminal record, access to violence). In other words, meaningful

clusters of points (for instance, actors and tasks performed) can be obtained. Yet, this

technique does not allow us to explore cluster of actors based on formal measures ofcentrality nor to reconstruct the informal structure on the basis of the contacts among

actors, or conclude whether the group is structured hierarchically or not. In order to

undertake such analysis, one needs to turn to Social Network Analysis.

Social network analysis (SNA)

Phone conversations are by their very nature relational. SNA is a technique that

allows us to map connections, describe the strength of the relationship between

actors, and test hypotheses about who is likely to be connected to whom over time.

In order to apply such a technique, one needs to develop measures of connection

between actors. A starting point is to count how many times two actors call each

other. This measure enables the researcher to gauge the intensity of the relationship

(based, for instance, on the number of times they spoke on the phone or on the

number of words exchanged overall). If one has the date of each call, one can create

a third data set, a Longitudinal Directed Network, split at various points in time.

Longitudinal network data are typically collected as panel data where the

relationship between network actors is observed at two or more discrete points in

time. There are at least two different ways to split such a Longitudinal Network. One

solution would be to have a time-based split, e.g. every three months. A second

approach is to have an event-based split. In this case, the researcher would decide

which relevant events might warrant a split in the data. Such events might include a

15 Given the chi-square distances feature of increasing the relative contribute of the components with lower

masses, it is better to be very careful when modalities with very low mass are included into the analysis.

24 Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

13/18

murder, a police intervention or any other theoretically relevant event. Finally, one

can create a non-network matrix of attributes of actors (e.g., gender, nationality, tasks,

use of force) to be matched to the actors in the network matrix.

SNA can help reconstruct the internal structure of a criminal network (hierarchical

vs. flat), on the basis of the pattern of ties actors have with each other as opposed totheirofficialtitle. Seen through the lens of SNA, a hierarchy can be thought of as a

special pattern of relations, namely a network where the vast majority of ties flow to

or from a few nodes (Podolny and Page1998: 59; Knoke and Rogers1979; Lauman

1991). The internal structure uncovered by SNA is the informal one. In other words,

we might know that a boss, an underboss and several team leaders exist in a group,

but we are interested in how they relate to each other informally: a charismatic team

leader might have direct access to the boss, bypassing the formal hierarchy. Such a

feature might predict future promotion, or conflict. Furthermore, SNA allows us to

identify key brokers (Burt1992).The SNA suggests that different patterns of connection between actors produce

different levels ofcentralization. The more connections go through a given node, the

more central such a node will be within the network. A highly central node

occupies a high level within the informal pattern of relationships in the group, even

if the actor in question does not sit at the top of the official organizational pyramid.

Centrality can thus be the operationalization of the concept of hierarchy.16

Several

measures of centrality have been devised by SNA (e.g. degree centrality and node

betweenness: Freeman 1979; Wasserman and Faust 1994) and are implemented in

most software, such as UCINET (Borgatti et al. 2002) and Pajek (de Nooy et al.2005).

SNA can also help reconstruct the internal cohesion of the network through a

variety of algorithms (see, e.g., Amorim et al.1992; Borgatti et al.2002; Hanneman

and Riddle2005: ch. 11). Yet, most of these measures are descriptive and refer to the

network at one point in time only.17 Scholars would want to go beyond descriptive

measures of networks and try to test hypotheses. Examples of hypotheses that could

be tested are whether, say, actors of the same nationality are more likely to form a tie

than actors of different nationality; whether women are more likely to form ties with

other women than with men. In addition to hypotheses that test the effect of specific

attributes (e.g. nationality, gender), one might want to test peculiar network

hypotheses, such as reciprocity (if you phone me, I shall phone back) and

transitivity (if both you and I phone her, we shall phone each other; on this, see

also Robins2009). To put it in the classical terminology of statistical analysis, the

dependent variable is the likelihood of tie formation among two actors. However,

network data have a peculiar structure: actors are located both on the rows and the

16 Hierarchy could of course be defined differently, for instance as a structure embodying relations of

authority and subordination. Such a concept could be operationalized by looking for items in aconversation that would suggest the relative status of the speakers (Natarajan 2000). Giving orders,

expressing satisfaction, and requesting information would indicate a high position in the informal

hierarchy of the group (Natarajan 2000). Provided one has such information from the conversation, a

content analysis can be undertaken.17 The notable exception is the so-called QAP procedure that regresses one or more independent matrices

on a dependent matrix, and assesses the significance of the r-square and regression coefficients (the

procedure is implemented in UCINET software. See Borgatti et al.2002).

Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330 2525

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

14/18

columns of a data matrix, while standard representations of data in a matrix list cases

on the rows and variables on columns. Thus, when it comes to data analysis,

standard methods such as general linear model analysis cannot be used because

they assume independence of observations (Robins and Kashima 2008). The

complicated dependence structures inherent in network data call for novel andadvanced statistical techniques. Theoretical statisticians have now developed reliable

ways to calculate coefficients for network data. The most commonly used is the

stochastic actor-oriented model proposed by Snijders (2001; see also Burk et al.

2007). The stochastic actor-oriented model allows us also to test a variety of network

effects, such as whether ties are likely to be reciprocated, as well as non-network

effects. It is also able to model network evolution, provided the data allow it (i.e. if

one has data of the network collected at different points in time). In the presence of a

large enough sample of conversation, one would normally have the time of the

conversation, thereby constructing the data set as a panel. Network evolution canthen be explored, telling us whether the group becomes more cohesive or more

fragmented over time. An additional advantage of using the stochastic actor-oriented

model is that it is implemented in an easy-to-use software, SIENA (Snijders et al.

2007).18 This method is increasingly used in other subfields of criminology (see,

e.g., Dijkstra et al. 2010).

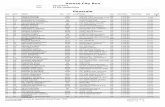

What these techniques tell us about criminal groups

Table 1 presents a summary of the insights that might be obtained from the fourdifferent techniques we have discussed so far.

Content Analysis draws only on data contained in the conversations intercepted

by the police. Information about actors emerges as long as it is contained in the

conversations. Content Analysis is able to extract aggregate data on the whole

corpus of conversations, e.g., the most talked about themes and the countries of

origin and destination of the calls. In this way, it is therefore possible to empirically

reconstruct the activities of a criminal group, and relative relevance of such activities

(e.g. it may be argued that the greater the number of segments of conversation

devoted to a specific task, the more relevant the task is for a given group). Content

Analysis also allows us to have summary information on individual actors, for

instance about whom they talk to most, which country they call, which themes they

discuss. The key limitation is that actors are considered, as it were, separately.

Correspondence Analysis allows us to combine two sets of data, one derived from

the conversations and one derived from other sources regarding actors attributes. It

detects the presence of clusters based on patterns of relations between attributes of

both actors and conversations. For example, instances of division of labour within

the group may be detected in this way.

Social Network Analysis enables us to reconstruct the informal structure of a

criminal group based on the number of ties exchanged by the actors involved, the

internal hierarchy and cohesiveness of a group. SNA also helps detect clusters of

18 The actor-oriented models implemented in SIENA software have some limitations. For instance, these

models do not produce a measure similar to the reproduced variance and it is not possible to compare

statistics estimated by SIENA with statistics calculated via other statistical techniques (Snijders et al.2007;

Burk et al. 2007: 403).

26 Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

15/18

actors based on the patterns of ties they have with each other (as measured by their

phone ties). Through the stochastic actor-oriented model one can test hypotheses ontie formation on the basis of a variety of independent variables, both network

variables and non-network variables. It is possible to estimate the evolution of a

criminal group over time, taking into account at the same time the characteristics of

the actors involved (exogenous variables) and those of the network structure

(endogenous variables).

Conclusions

In the past years SNA has been widely adopted for the study of criminal groups. A

relatively neglected source of data is phone conversations wiretapped by the police.

Such a source poses no threat to the researcher and has the potential to capture

criminal talk as it occurs in its natural setting, involving both high-ranking and low-

ranking members. In this paper, we have spelled out three prerequisites that should

be met for rigorous analysis of this type of data. Individuals under surveillance must

talk freely on the phone, the coverage of the group must be reasonably wide, and a

large enough sample of conversations must be available for analysis. Wiretapped

conversations are a type of purposive sample created by officers. Thus errors of Type

I (a criminal conversation is not recorded by the police) and Type II (a non-criminalconversation is recorded) can occur. Only Type I errors pose a threat to validity,

because the researcher can always discard superfluous conversations. As long as one

does not wish to estimate the ratio of criminal to non-criminal conversations, the

purposive nature of the sample should not distort analysis. Scholars should however

be careful not to use small sub-samples of conversations contained in certain court

Table 1 Techniques, data sets used and results achieved

Technique Data Sets Used Results

Content Analysis Conversations - Features of the conversations

(e.g. most talked topics).

- Features of actors as they emerge

from conversations.

- More generally, activities both at the

individual and group level.

Correspondence Analysis Conversations and Actorsa - Clusters based on attributes of both

actors and conversations

(e.g. internal division of labour)

Social Network Analysis Conversations and Actors - Informal hierarchy

- Clusters (factions) based on patterns of ties

Longitudinal stochastic

actor-oriented model

Conversations and Actors - Testing hypotheses on attribute(s) and

network effects on tie formation

- Assessing the network evolution over time

aActorsrefers to data not included in the conversations per se, but extracted from other sources, such as

interviews or police files

Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330 2727

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

16/18

-

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

17/18

Burk WJ, Steglich CEG, Snijders TAB (2007) Beyond dyadic interdependence: actor-oriented models for

co-evolving social networks and individual behaviours. Int J Behav Dev 31(4):397404

Burt RS (1992) Structural holes: the social structure of competition. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Campana P (2011). Eavesdropping on the Mob: the functional diversification of the Mafia activities across

territories. Eur J Criminol 8(3):116

Coles N (2001) Its notwhatyou knowItswho you know that counts. Analysing serious crime groupsas social networks. Br J Criminol 41(4):580594

de Nooy W, Mrvar A, Batagelj V (2005) Exploratory social network analysis with Pajek. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge

Dijkstra JK, Lindenberg S, Veenstra R, Steglich C, Isaacs J, Card NA, Hodges EVE (2010) Influence and

selection processes in weapon carrying during adolescence: the roles of status, aggression, and

vulnerability. Criminology 48:187220

Finckenauer JO, Waring EJ (1998) Russian Mafia in America: immigration, culture and crime.

Northeastern University Press, Boston

Freeman LC (1979) Centrality in social networks: conceptual clarification. Soc Netw 1:215239

Gifi A (1990) Nonlinear multivariate analysis. Wiley, Chichester

Greenacre MJ (1984) Theory and application of correspondence analysis. Academic, London

Hanneman RA, Riddle M (2005) Introduction to social network methods. University of California,Riverside. At:http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/

Harcourt BE (2002) Measured interpretation: introducing the method of correspondence analysis to legal

studies. Univ Ill Law Rev 9791017

Hill MO (1974) Correspondence analysis: a neglected method. Appl Stat 23(3):340354

Hirschfeld HO (1935) A connection between correlation and contingency. Proc Camb Philos Soc (Math

Proc) 31:520524

Holsti OR (1969) Content analysis for the social sciences and humanities. Addison-Wesley Publishing

Company, Reading

Horst P (1935) Measuring complex attitudes. J Soc Psychol 6:369374

Klerks P (2001) The network paradigm applied to criminal organisations: theoretical nitpicking or a relevant

doctrine for investigators? Recent developments in the Netherlands. Connections 24(30):53

65Knoke D, Rogers DL (1979) A blockmodel analysis of interorganizational networks. Sociol Soc Res

64:2852

Krippendorff K (2004) Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology, 2nd edn. Sage, Beverly Hills

Lauman EO (1991) Comment on The future of bureaucracy and hierarchy in organizational theory: a

report from the field. In: Bourdieu P, Coleman JS (eds) Social theory for a changing society.

Westview, Boulder, pp 9093

Lauman EO, Marsden PV, Prensky D (1983) The boundary specification problem in network analysis. In:

Burt RS, Minor MJ (eds) Applied network analysis. Sage, Beverly Hills, pp 1834

McNally D, Alston J (2006) Use of Social Network Analysis (SNA) in the examination of an outlaw

motorcycle gang. J Gang Res 13(3):125

Mohr JW (1998) Measuring meaning structures. Annu Rev Sociology 24:345370

Mohr JW, Duquenne V (1997) The duality of culture and practice: poverty relief in New York City, 18881917. Theory Soc 26:305356

Morselli C (2005) Contacts, opportunities, and criminal enterprise. University of Toronto Press, Toronto

Morselli C (2009) Inside criminal networks. Springer, New York

Natarajan M (2000) Understanding the structure of a drug trafficking organization: a conversational

analysis. In: Natarajan M, Hough M (eds) Illegal drug markets: from research to policy. Crime

preventions studies, Vol. 11. Criminal Justice Press, Monsey, pp 273298

Natarajan M (2006) Understanding the structure of a large heroin distribution network: a quantitative

analysis of qualitative data. J Quant Criminol 22:171192

Pattison PE, Breiger RL (2002) Lattices and dimensional representations: matrix decompositions and

ordering structures. Soc Netw 24:423444

Podolny JM, Page KL (1998) Network forms of organizations. Annu Rev Sociology 24:5776

Reuter P (1994) Research on American Organized Crime. In: Kell R, Chin K, Schatzberg R (eds)

Handbook of organized crime in the United States. Greenwood, Westport, pp 91119

Richardson M, Kuder GF (1933) Making a rating scale that measures. Pers J 12:3640

Roberts CW (ed) (1997) Text analysis for the social sciences: methods for drawing statistical inferences

from texts and transcripts. Erlbaum, NJ

Robins G (2009) Understanding individual behaviours within covert networks: the interplay of individual

qualities, psychological predispositions, and network effects. Trends Organ Crime 12(2):166187

Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330 2929

http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/ -

8/10/2019 Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federic

18/18

Robins G, Kashima Y (2008) Social psychology and social networks. Asian J Soc Psychol 11(1):112

Schlegel K (1984) Life Imitating Art: Interpreting Information from Electronic Surveillances. In: Fairbank

JK (ed) Critical issues in criminal investigations. Criminal Justice Press, Cincinnati, pp 5361

Scott J (2000) Social network analysis. A handbook, 2nd edn. Sage, London

Smith DC (1975) The Mafia mystique. Basic Books, New York

Snijders TAB (2001) The statistical evaluation of social network dynamics. Sociol Methodol 31:361395Snijders TAB, Steglich CEG, Schweinberger M, Huisman M (2007) Manual for SIENAversion 3.1. University

of Groningen: ICS / Department of Sociology and University of Oxford: Department of Statistics

TM(Tribunale di Monza) (1994) Atti del procedimento contro Sansalone Antonio (Proceedings against

Sansalone Antonio), Monza Penal Court

Torgerson WS (1952) Multidimensional scaling: I. Theory and method. Psychometrika 17(4):40119

Varese F (2006) The structure of a criminal network examined: the Russian Mafia in Rome. Oxford Legal

Studies Research Paper 21. University of Oxford, Oxford

Varese F (2010) General introduction. What is organized crime? In: Varese F (ed) Organized crime.

Routledge, London and New York, pp 133

Varese F (2011) Mafias on the move. Princeton University Press, Princeton

von Lampe K (2009) Human capital and social capital in criminal networks: introduction to the special

issue on the 7th Blankensee Colloquium. Trends Organ Crime 12(2):93100Wasserman S, Faust K (1994) Social network analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Weber RP (1990) Content analysis, 2nd edn. Sage, Beverly Hills

30 Trends Organ Crim (2012) 15:1330

![download Trends in Organized Crime Volume 15 Issue 1 2012 [Doi 10.1007%2Fs12117-011-9131-3] Paolo Campana; Federico Varese -- Listening to the Wire- Criteria and Techniques for the Quantitative](https://fdocuments.in/public/t1/desktop/images/details/download-thumbnail.png)