Transient Ischemic.pdf

-

Upload

dennis-cobb -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

0

Transcript of Transient Ischemic.pdf

-

50 december 13 :: vol 21 no 14-16 :: 2006 NURSING STANDARD

learning zoneCONTINUING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT

Aims and intended learning outcomes

The aim of this article is to raise awareness oftransient ischaemic attack (TIA) by explaining itsclinical significance, and the importance ofprompt specialist assessment. This knowledgewill help nurses to direct and support patients toaccess appropriate care and undertake self-management after the event.

After reading this article you should be able to:

Understand the significance of TIA as a markerof vascular risk.

Describe the clinical features of a TIA.

Identify key investigations required todetermine the cause of TIA.

Discuss current evidence-based secondaryprevention treatment that reduces the risk offurther vascular events.

Demonstrate awareness of The StrokeAssociations Act FAST campaign.

Identify how to find out about local TIAservices in your area.

Introduction

Transient ischaemic attack (TIA) produces briefstroke-like symptoms due to a temporarydisruption of blood to the brain and is sometimesreferred to as mini-stroke (Figure 1). TIAs donot kill or leave patients with lasting disability,but they are a warning sign that an individual is atrisk of further vascular events such as stroke ormyocardial infarction (MI). The identification ofTIAs raises the opportunity to prevent moreserious vascular events.

Accurate diagnosis of TIA, includingidentification of the cause of the event, isnecessary to reduce immediate and future risks(Hankey 2003). The transient nature ofsymptoms presents a challenge, because attackscan be unrecognised and under-reported bypatients (Kelly et al 2001). Accuracy of diagnosisis problematic because it is heavily dependent oncorrect interpretation of the history taken fromthe patient in the absence of ongoing symptoms(Martin et al 1997, Kelly et al 2001).

Rapid-access TIA and neurovascular clinicsfor specialist assessment of TIA should be anintegral part of a stroke service (Department ofHealth (DH) 2001). Integrated services shouldinclude prevention, immediate care, early andcontinuing rehabilitation and long-term support.TIA and neurovascular clinics address prevention

NS372 Beech P (2006) An overview of transient ischaemic attack. Nursing Standard. 21, 14-16, 50-57.Date of acceptance: August 1 2006.

SummaryThis article provides an overview of transient ischaemic attack(TIA). It discusses the clinical presentation of TIA, its significanceas a marker of vascular risk, key diagnostic interventions andmanagement strategies. Trends and challenges in service provisionand the roles of specialist and general nurses in managing patientswith TIA are explored.

AuthorPaula Beech is health services researcher, Public Health, SalfordPrimary Care Trust, Salford. Email: [email protected]

KeywordsStroke; Stroke services; Transient ischaemic attack

These keywords are based on the subject headings from the BritishNursing Index. This article has been subject to double-blind review.For author and research article guidelines visit the NursingStandard home page at www.nursing-standard.co.uk. For relatedarticles visit our online archive and search using the keywords.

An overview of transient ischaemic attack

Page 58Neurovascular nursing multiplechoice questionnaire

Page 59Read Janet Richards practice profileon information governance

Page 60Guidelines on how towrite a practice profile

p50-57w14-16 7/12/06 11:07 am Page 50

-

and immediate care. According to a recent reporton stroke services only 55 per cent of hospitalsnationally had agreed TIA protocols betweenacute and primary care (National Audit Office(NAO) 2005).

National stroke guidelines recommend rapidaccess to TIA and neurovascular clinics forspecialist stroke assessment to prevent future illhealth. Recommended timeframes for accessingsuch services are stringent and are currentlywithin seven days of the event (Royal College ofPhysicians (RCP) 2004).

Defining transient ischaemic attack

TIA has been defined as (Warlow et al 2001): A clinical syndrome characterised by an acuteloss of focal cerebral or monocular function withsymptoms lasting less than 24 hours and which isthought to be due to inadequate cerebral orocular blood supply as a result of low blood flow,arterial thrombosis or embolism associated withdisease of the arteries, heart or blood.

TIA symptoms are known to:

Occur without warning.

Affect a specific location or function of the brainor affect vision in one eye.

Be brief, lasting less than 24 hours actualduration is usually less than an hour, oftenseconds or minutes.

Occur because the blood supply to the brain oreye is disrupted.

A TIA may present with any of the symptoms of alasting stroke. Symptoms depend on the part ofthe blood supply to the brain that has been

disrupted, that is, the vascular territory, and thefunctions of the area of affected brain. Other keyaspects of TIA symptoms are that they are mostsevere at onset and resolve gradually, and thatthey are usually negative, for example, loss ofsensation, and rarely positive, for example,paraesthesia (pins and needles).

Disease of the blood vessels is the mostcommon reason (75-80 per cent) for disruptedbrain blood flow. Such diseases are large arteryatherothrombosis, for example, carotid stenosis,small artery atheroma and non-atheromatousdisease, for example, arterial dissection. Otherreasons for disrupted blood flow includeembolism from the heart (20 per cent) anddisorders of the blood (less than 5 per cent), forexample, prothrombotic states (Hankey 2001).

Significance of transient ischaemic attack

TIAs affect 51 in 100,000 people per year in theUK (Rothwell et al 2004). They occur morefrequently with increasing age, and are more

december 13 :: vol 21 no 14-16 :: 2006 51NURSING STANDARD

Time out 1Reflect on an experience of dealing with a patient with TIA? What was theoutcome for the patient? Did he or she haveaccess to specialist stroke services?Search the internet for key documents toinform your reflection on whether anintegrated stroke service is available locally: National Service Framework for Older People

(DH 2001) (www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/07/12/83/04071283.pdf)National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke

(RCP 2004) (www.rcplondon.ac.uk/pubs/books/stroke/index.htm) National Audit Office (2005) Department of

Health. Reducing Brain Damage: FasterAccess to Better Stroke Care(www.nao.org.uk/publications/nao_reports/05-06/0506452.pdf) (Last accessed:December 1 2006.)

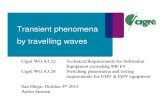

FIGURE 1

Blood clot from atherothrombosis leading to transient ischaemic attack

Aorta

Right vertebral artery

Right carotid artery Arterywall

Blood clotforms onatheroma

Part of the blood clot breaks off and blocks asmall artery in the brain

Atheroma

Time out 2Review the following anatomy and physiology using available resources:Carotid artery An important artery supplyingblood to the brain. Narrowing of this artery cancause TIA.Atherothrombosis of arteries What happens tothe arteries in cases of atherothrombosis?How do they narrow? How are small thrombiproduced that can embolise in the bloodstream?Narrowing of the carotid artery andatherothrombosis of the arteries are two waysthat blood supply to the brain can be disrupted.

p50-57w14-16 7/12/06 11:07 am Page 51

-

Diagnostic issues

Diagnosis of TIA can be difficult because of thetransient nature of the symptoms. Obtaining anaccurate patient history is crucial to guideappropriate treatment and secondary prevention,and assists in targeting resources appropriately.

Several factors should be considered to obtainan accurate history and examination (Box 1). The patients ability to recall events, theavailability of a witness to clarify details, the siteand duration of disrupted blood flow, patientactivity at the time of event, the patients ability tocommunicate about the event and the cliniciansexperience in eliciting and interpreting theaccount are all important.

Clear identification of specific symptomsexperienced by the patient can help to identify theaffected area of the brain/vascular territory andguide future investigation and treatment. Specific(focal) symptoms associated with disruption tothe anterior or posterior blood supply are shownin Box 2.

Non-specific (non-focal) symptoms, such asloss of consciousness, particularly with noaccompanying focal symptoms, are unlikely toindicate TIA (Hankey 2001). Other conditionsthat may cause similar symptoms to TIA need tobe considered as differential diagnoses (Box 3).

Over-diagnosis of TIA is common and wastestime and resources (Davies and Rodgers 2001). Areview of referrals to a regional neurovascularclinic found that, of 332 TIA referrals, 40 per centof patients had not experienced a TIA (Martin et al 1997). Similar diagnostic confirmation rateswere revealed in a national survey of TIA clinicsundertaken by the author as part of serviceevaluation (Beech 2004). Ensuring that TIA iscorrectly identified is a key aim of specialistassessment.

Interventions and management

Key investigations Investigations are undertakento clarify diagnosis and establish an underlyingcause. Specific investigation decisions are based onsymptoms, age, physical condition and willingnessto undergo testing and treatment (Box 4).

Early access to computed tomography (CT)and carotid Doppler (ultrasound scan of carotidarteries in the neck) assessment, whereappropriate, are needed for optimal management(Lees et al 2000, Wardlaw et al 2003). However,access to these assessments for local services canbe limited (NAO 2005, Beech et al in press).

Treatment goals for TIA are to improve bloodsupply to the brain, treat any specific underlyingcauses, minimise risk factors for heart disease andstroke and reduce the likelihood of future events.Prophylactic treatment, management of lifestyle

common in men than women during middle age.Despite the short duration of TIA symptoms

and absence of residual disability, patients withTIA require an active approach because the riskof further events remains high. Ignoring thewarning by failing to seek specialist assessmentand intervention can have serious consequencesfor patients. Some clinicians and members of thepublic perceive TIAs as benign events (Krieger2005). This view must change TIA is a cue to actto reduce the risk of future disability or death.

In the first seven days after TIA the risk ofstroke has been commonly quoted as 1-2 per centand within the first month as 4 per cent (Warlow etal 2001). New data now put the seven-day risk ofstroke post-TIA at 8 per cent and the one-monthrisk at 12 per cent (Coull et al 2004). Heart diseaseis the most likely cause of death post-TIA (Hankeyand Warlow 1994).

MI and stroke are the second and third rankedcause of death in the UK and stroke the primarycause of adult disability. Therefore, TIA providesan opportunity to start treatment andbehavioural change to reduce the risk of earlydeath or disability.

The risks described are also the reason thatpatients should not drive for a month followingTIA (Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency 2006).

When a patient presents with a suspected TIA,five questions should be asked (Hankey 2001):

Is the event a TIA?

If it is a TIA, what is its location? What is theaffected part of the brain or eye indicating thearea of blood supply that is affected?

What is the cause of the TIA?

What are the chances of a future MI or stroke?

What actions will reduce the risk of a future MIor stroke?

learning zone neurovascular nursing

52 december 13 :: vol 21 no 14-16 :: 2006 NURSING STANDARD

Clinical history:Age

Symptom nature, onset andduration

Past medical history, includingmedication, vascular risk factors and family history

Examination:Pulse rate and rhythm

Blood pressure

Carotid bruit

Heart murmurs

Eye examination

Full neurological examination

Evidence of vascular diseaseelsewhere

Body weight

BOX 1

History and examination

(Hankey 2001)

p50-57w14-16 7/12/06 11:07 am Page 52

-

factors and patient education are key approachesto TIA management.Prophylactic treatment Anti-thrombotic agents(antiplatelet agents and anticoagulation) are themain form of treatment. They thin the blood toreduce the incidence of further disrupted bloodsupply to the brain. Anti-thrombotic drugsshould be withheld if symptoms are present whenpatients first seek medical advice. In such cases,the patient should be admitted for specialistassessment, including a computed tomography(CT) scan, to confirm the absence of bleeding inthe brain. This form of disruption to the brainblood supply is possible when symptoms persist,but it is unlikely when symptoms last briefly, as incases of TIA.

There is trial evidence to support the use of anumber of antiplatelet agents and there has beensome controversy about the best antiplatelet agentfollowing TIA. Aspirin has been the mainstay oftreatment for many years (AntithromboticTrialists Collaboration 2002) and in the case ofsuspected TIA where symptoms resolvecompletely, patients may start on a single 300mgdose reducing to 75mg once a day (Hankey 2001).Dipyridamole modified release (Persantin) anddipyridamole modified release/aspirincombination therapy (Asasantin) (Diener et al1996) and clopidogrel (CAPRIE SteeringCommittee 1996) have also been in use.

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence(NICE) recently produced a technology appraisal(NICE 2005) to clarify practice. This documentsuggests that all patients with stroke or TIAshould be treated with Asasantin, one capsuletwice daily for two years post event and then betreated with aspirin 75mg. Clopidogrel isrecommended only for patients with true aspirinintolerance defined as proven hypersensitivity or ahistory of severe dyspepsia.

Since the recommendation from NICE thevalue of Asasantin instead of aspirinmonotherapy has been further supported by therecent publication of the ESPRIT trial (ESPRITStudy Group et al 2006). Some patients developheadache with Asasantin and the alternative is areturn to aspirin 75mg. Patients with indigestionon aspirin can be advised to take their medicationwith meals and if this fails a proton pumpinhibitor can be added to suppress symptomsrather than immediately changing from aspirintherapy (Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin 2005).

Where atrial fibrillation is discovered as anunderlying cause of TIA, this is the mainindication for anticoagulation (warfarin therapy)in patients who do not have contraindications toits use. For those with a history of falls, cognitiveimpairment or difficulties maintaininganticoagulant monitoring, long-term therapy onaspirin 300mg daily is an alternative.

Anticoagulation reduces the risk of ischaemicstroke by about two thirds (European AtrialFibrillation Trial Study Group 1993).

An international normalised ratio of 2.0-3.5 is a target that should be maintained foranticoagulation therapy (European AtrialFibrillation Trial Study Group 1995). Otherpatients who may require anticoagulationinclude those with mitral valve disease,prosthetic heart valves and recent MI (withinthe past three months). Although following astroke warfarin is usually avoided until CT scanhas excluded haemorrhage and 14 days havepassed since the TIA with full resolution ofneurological symptoms, the physician maywant to institute warfarin earlier.

High blood pressure is the primary risk factorfor TIA and stroke. It is treatable and should be

december 13 :: vol 21 no 14-16 :: 2006 53NURSING STANDARD

Anterior circulation:Right or left-sided weakness of limbs or face.

Right or left-sided sensory symptoms of limbs orface.

Amaurosis fugax (transient loss of vision in oneeye).

Dysphasia.

Posterior circulation:Ataxia (loss of co-ordination).

Diplopia (double vision).

Dysphagia.

Homonymous hemianopia (loss of vision in right orleft half of visual field of both eyes).

Weakness and sensory symptoms on one or bothsides of the body.

(Davies and Rodgers 2001)

BOX 2

Symptoms associated with disruption to thecirculation

Arrhythmic episodes

Cancer

Chronic subdural haematoma slow developingblood clot on brain

Hyperventilation

Hypoglycaemia

Migraine

Positional vertigo

Seizures

Syncope

BOX 3

Differential diagnoses to transient ischaemicattack

p50-57w14-16 7/12/06 11:07 am Page 53

-

Clinical assessment should include determiningwhether carotid endarterectomy is needed.Carotid Doppler assessment is the first step indeciding if patients are suitable for carotidendarterectomy, a surgical procedure formanaging narrowing of the carotid artery thatmay lead to stroke. Carotid Doppler assessment is used specifically in patients with a suspectedanterior circulation TIA.

Carotid Doppler screening establishes thedegree of narrowing of the carotid artery. Thisinformation helps to determine whether the risksto the patient of this type of surgery are worthtaking. If carotid narrowing is greater than 70 percent, the patient should be referred to a specialistvascular surgeon experienced in carotidendarterectomy and with a low complication rate(European Carotid Surgery TrialistsCollaborative Group 1998, North AmericanSymptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy TrialCollaborators 1998).

Following any cerebrovascular event, includingTIA, fasting total cholesterol should be obtained. Ifthis is greater than 3.5mmol/l dietary advice shouldbe offered and treatment with a statin considered(RCP 2004). Simvastatin is the statin of choicebecause it has the most trial evidence to support itsuse (Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin 2005).

Diabetes mellitus must be excluded by bloodsugar measurement. If diabetes mellitus ispresent, risk of stroke in those with the conditionis one and a half to three times higher than thosewithout diabetes. Strict blood sugar control hasno proven benefit for reducing large blood vesseldisease and stroke risk (Idris et al 2006). Thishighlights the need for strict management of othervascular risk factors to help minimise risks in thispatient group.Patient education and lifestyle Patients needadvice, encouragement and support to undertakerelevant lifestyle change that will reduce the risk offuture stroke and MI. Areas of lifestyle to beaddressed are smoking, weight, diet, salt intake,exercise and alcohol consumption.

Smoking is the second most important riskfactor for stroke. It has a synergistic effectmultiplying the effect of other risk factors.Smoking cessation is associated with considerableand rapid decrease in stroke risk, as the benefitsare apparent within five years of cessation(Wannamethee et al 1995). Smoking cessationshould be encouraged whenever possible.Smokers should be asked about their willingnessto stop and directed to available support.

Patients should be given dietary advice andencouraged to eat at least five portions of fruitand vegetables a day and to reduce their intake ofsaturated fat (Ness and Powles 1999). Reducingsalt in the diet can lower blood pressure and,therefore, risk of stroke.

actively managed according to available guidelines(Williams et al 2004, National CollaboratingCentre for Chronic Conditions 2006). Each10mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure mayconfer a stroke risk reduction of approximatelyone third in patients aged 60 to 79 years (Lawes et al 2004). This relationship is age-dependent butremains strong and positive in those aged 80 yearsand older. Systolic and diastolic readings areimportant.

Regular monitoring to achieve target bloodpressure is crucial. It is preferable that patientsknow their target blood pressure. Patients andprimary care staff share the responsibility forensuring adequate blood pressure monitoringand reduction.

Achieving a reduction in blood pressure close totarget figures is crucial for reducing future MI andstroke, regardless of the specific choice of drugs(Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin 2005).

learning zone neurovascular nursing

54 december 13 :: vol 21 no 14-16 :: 2006 NURSING STANDARD

Essential investigationsFull blood count

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Plasma glucose (blood sugar)

Cholesterol

Electrocardiogram

Additional investigations:Computed tomography

Carotid Doppler

Magnetic resonance imaging

Echocardiography, where embolism from the heartis suspected

Other tests may need to be considered

(Hankey 2001)

BOX 4

Key investigations for patients with transient ischaemic attack

Time out 3Consider a patient you have cared for with a history of TIA or stroke. Was the patient on any preventive therapies?Are you aware of any stroke secondary prevention and/or treatment guidelines thatyou can refer to locally? If not, local medicinesmanagement groups and stroke teams shouldbe able to direct you to them.

p50-57w14-16 7/12/06 11:07 am Page 54

-

Weight loss with or without salt reduction isa safe and effective way of reducing bloodpressure in hypertensive older people. Thestandard measure for assessing obesity has beenbody mass index, which is calculated from anindividuals weight and height. Recent evidencesupports the use of waist-to-hip ratios as a moreaccurate marker for risk of heart attack andstroke (Yusuf et al 2005).

Physical activity may help to lower stroke risk(Evenson et al 1999). It should be encouragedwith sensitivity to the age and concurrent healthproblems of each individual.

Reducing alcohol intake that is above therecommended upper limits is advisable for itsbeneficial effects on blood pressure. However, theinteraction between alcohol consumption andstroke risk is a complex one (Mazzaglia et al 2001).

Assessment and advice in a specialist clinic is onlypart of the process of lifestyle change. Acting onadvice is the responsibility of the patient, with thesupport of primary care providers. Effectivecommunication between clinic staff, patients andprimary care colleagues is essential, practicevaries and should be agreed locally. This mayentail shared copies of discharge letters, writtenlifestyle management advice or the provision of atelephone contact.

It is important that patients with a confirmeddiagnosis of TIA leave the clinic with anunderstanding of how to prevent or deal withfuture problems. Patients need to access strokeservices rapidly if they require them in the futureand awareness of available services will optimisetheir chances of receiving treatments such asthrombolysis.

Thrombolysis is a treatment for patients withpersisting stroke symptoms not TIA that canreverse impairment by restoring blood flow to theaffected area of brain. It must be commencedwithin three hours of the onset of symptoms andis only available at selected and regulated centres(RCP 2004).

Attending the clinic provides an opportunityto communicate with the patient and his or herrelatives and/or carers about the need to respondquickly to TIA and stroke symptoms and theimportance of accessing acute stroke care. The

decision to seek advice for symptoms is ofteninfluenced by friends, relatives and carers. Clinicattendance is an opportunity for publicawareness raising that may be shared in the widercommunity.

Service provision

Patients with TIA have received varying levels ofmanagement from none at all, if advice is notsought, to GP management or referral to varioushospital specialists, including elderly care,vascular surgery, neurology or ophthalmology.The National Service Framework for OlderPeople (DH 2001) and the national guidelines forstroke (RCP 2004) recommended that thisvariation in treatment should stop and that strokespecialist assessment should be available rapidlyafter the event.

These policy drivers have resulted in increasednumbers of specialist assessment clinics (Beech et al in press). A survey of TIA services found thatthe number of specialist clinics has increased sincethe National Service Framework for Older Peoplewas introduced(Beech et al in press). However,clinic access times have not met national targets(NAO 2005). Classic outpatient service modelsmay not be sufficient to treat TIA. New models ofworking, for example, day case assessment, nurse-led clinics or the use of screening methods toprioritise cases, need to be agreed locally, testedand evaluated (Cahn 1998, Rothwell et al 2005).In response to the NAO (2005) report, strokeservices are under scrutiny by the DH. A newnational strategy is anticipated that will addresspersisting deficits in service provision. An 18-month programme of work for this waslaunched on March 1 2006 with working groupscovering public awareness and prevention, TIAservices, emergency response, hospital stroke care,post-hospital stroke care and workforce.

The nurses role

Nurses usually provide a psychosocial supportiverole to patients at risk of TIA and stroke. Themain aspects of providing support are directingpatients to key services, provision of appropriateand accurate information and listening to and

december 13 :: vol 21 no 14-16 :: 2006 55NURSING STANDARD

Time out 4Think about lifestyle changes that patients at risk of TIA may need to consider. Research available support servicesfor lifestyle change in your local area, forexample, smoking cessation services and supported exercise schemes. You may wish torecord these so they can be referred to whenadvising patients.

Time out 5How do you think public knowledge of warning signs for TIA and stroke canbe improved?Visit The Stroke Association websitewww.stroke.org.uk to view information aboutthe Act FAST campaign. Consider whether anyof these materials could be used to raiseawareness in your workplace.

p50-57w14-16 7/12/06 11:07 am Page 55

-

information to share the experience of theseservices. Nurses working in nurse-led TIA clinicsassess patients, co-ordinate investigations,provide patients with accessible information andeducation materials, and liaise with medicalcolleagues about diagnoses, treatment andmanagement. The experiences of these servicesneed to be shared and evaluated so that thecontribution of nursing to the management ofTIA can be assessed.

Non-specialist nurses Non-specialist nurses havean important role in identifying TIA. They needto be aware of the signs and significance of TIA,the importance of accessing specialist assessment

acknowledging the experience of the individualwith a TIA as they deal with its implications. Specialist nurses Specialist nurses working in astroke service provide accurate information andsupport patients. The emphasis is on helpingpatients and their families to understand thediagnosis, prognosis and means of preventing orresponding appropriately to further episodes.

Support for patients to achieve lifestyle changeand maintain long-term health and independencecan be provided directly to the patient and familyor indirectly through liaison with primary carecolleagues. Specialist nurses communicate withprimary care colleagues about individual cases.They may also provide stroke and TIAinformation materials for practices, groupworkshops and continuing professionaldevelopment updates.

Nurse-led TIA services have been established(Cahn 1998); however, there is limited written

learning zone neurovascular nursing

56 december 13 :: vol 21 no 14-16 :: 2006 NURSING STANDARD

Time out 6Find out if there is a TIA service in your area. This information will help you to advise patients with TIA symptoms andtheir friends and family. Investigate whetherreferral protocols have been agreed betweenacute and primary care.

Antithrombotic Trialists Collaboration(2002) Collaborative meta-analysis ofrandomised trials of antiplatelet therapyfor prevention of death, myocardialinfarction, and stroke in high risk patients.British Medical Journal. 324, 7329, 71-86.

Beech P (2004) A Study to Pilot a CrossSectional Descriptive Survey of thePractice of Stroke Physicians inDeveloping Transient Ischaemic AttackServices in the UK. Masters in researchdissertation, The University of Salford,Faculty of Health and Social Care.

Beech PR, Greenhalgh J, Thornton M,Tyrrell PJ (In press) A survey of thepractice of stroke physicians in developingtransient ischaemic attack services in theUK. Journal of Evaluation in ClinicalPractice.

Cahn A (1998) Stroke of genius. NursingTimes. 94, 47, 42-43.

CAPRIE Steering Committee (1996) Arandomised, blinded, trial of clopidogrelversus aspirin in patients at risk ofischaemic events (CAPRIE). The Lancet.348, 9038, 1329-1339.

Coull AJ, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM,Oxford Vascular Study (2004)Population based study of early risk ofstroke after transient ischaemic attack orminor stroke: implications for public edu-cation and organisation of services.British Medical Journal. 328, 7435, 326-328.

Davies T, Rodgers H (2001) Preventionof stroke after transient ischaemic attack.Prescriber. 12, 19, 78-84.

Department of Health (2001) NationalService Framework for Older People. TheStationery Office, London.

Department of Health (2003) Qualityand Outcomes Framework. The StationeryOffice, London.

Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, SiveniusJ, Smets P, Lowenthal A (1996)European Stroke Prevention Study. 2.Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid inthe secondary prevention of stroke.Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 143,1-2, 1-13.

Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency(2006) For Medical Practitioners at aGlance. Guide to the Current MedicalStandards of Fitness to Drive. DVLA,Swansea. www.dvla.gov.uk/media/pdf/medical/aagv1.pdf (Last accessed:November 20 2006.)

Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin (2005)Drugs to prevent vascular events afterstroke. Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin.43, 7, 53-56.

ESPRIT Study Group, Halkes PH, vanGijn J, Kappelle LJ, Koudstaal PJ, AlgraA (2006) Aspirin plus dipyridamoleversus aspirin alone after cerebralischaemia of arterial origin (ESPRIT):randomised controlled trial. The Lancet.367, 9523, 1665-1673.

European Atrial Fibrillation TrialStudy Group (1993) Secondary preven-tion in nonrheumatic atrial fibrillationafter transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke. The Lancet. 342, 8882,1255-1262.

European Atrial Fibrillation TrialStudy Group (1995) Optimal oralanticoagulant therapy in patients withnonrheumatic atrial fibrillation and recentcerebral ischemia. The New EnglandJournal of Medicine. 333, 1, 5-10.

European Carotid Surgery TrialistsCollaborative Group (1998) Randomisedcontrolled trial of endarterectomy forrecently symptomatic carotid stenosis:final results of the MRC European CarotidSurgery Trial (ECST). The Lancet. 351,9113, 1379-1387.

Evenson KR, Rosamond WD, Cai J et al(1999) Physical activity and ischemicstroke risk. The atherosclerosis risk incommunities study. Stroke. 30, 7, 1333-1339.

Hankey GJ (2001) Management of thefirst-time transient ischaemic attack.Emergency Medicine (Fremantle, WA). 13,1, 70-81.

Hankey GJ (2003) Long-term outcomeafter ischaemic stroke/transientischaemic attack. CerebrovascularDiseases. 16, Suppl 1, 14-19.

Hankey GJ, Warlow CP (1994) TransientIschaemic Attacks of the Brain and Eye.WB Saunders, London.

References

p50-57w14-16 7/12/06 11:07 am Page 56

-

rapidly and how patients can access treatmentlocally. Many patients require prompting topresent for specialist assessment. Nurses with thecorrect information can influence an individual toseek advice and specialist assessment.Non-specialist nurses can support patients withlifestyle change and treatment decisions duringone-off admission or as part of an ongoingprofessional relationship in primary care.Knowledge of the risk factors for stroke andstrategies for managing these risk factors areimportant for communicating confidently anddeveloping management strategies with patients.

Conclusion

This article provides an overview of the riskfactors, management strategies and resources tosupport patients and reduce risk of MI and stroke.Applying this information in primary care maysupport fulfilment of the Quality and OutcomesFramework (QOF) that is part of the GeneralMedical Services contract for general practiceintroduced in 2004. QOF provides financial

reward for the achievement of quality points forspecific diseases including stroke (DH 2003).

TIA is a warning to patients and healthcarestaff of the risk of future MI or stroke. The risk offuture stroke in the first seven days after TIA ishigher than previously reported. It is essentialthat patients with likely TIA symptoms undergorapid specialist assessment within seven days ofthe event. Specialist assessment is vital becauseaccurately diagnosing a TIA is difficult but crucialfor guiding effective preventive management.

All nurses have a role in providing informationto patients and directing them to appropriateservices rapidly. Those with a role in primary carein particular are fundamental to advising andsupporting risk management strategies forpatients at risk of MI and stroke NS

december 13 :: vol 21 no 14-16 :: 2006 57NURSING STANDARD

Time out 7Now that you have finished the articleyou may like to write a practice profile.Guidelines to help you are on page 60.

Idris I, Thomson GA, Sharma JC(2006) Diabetes mellitus and stroke.International Journal of Clinical Practice.60, 1, 48-56.

Kelly J, Hunt BJ, Lewis RR, Rudd A(2001) Transient ischaemic attacks:under-reported, over-diagnosed, under-treated. Age and Ageing. 30, 5,379-381.

Krieger DW (2005) Should patients withTIAs be hospitalized? Cleveland ClinicJournal of Medicine. 72, 8, 722-724.

Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Feigin VL,Rodgers A (2004) Blood pressure andstroke: an overview of published reviews.Stroke. 35, 4, 1024-1033.

Lees KR, Bath PM, Naylor AR (2000)ABC of arterial and venous disease.Secondary prevention of transientischaemic attack and stroke. BritishMedical Journal. 320, 7240, 991-994.

Martin PJ, Young G, Enevoldson TP,Humphrey PR (1997) Overdiagnosis ofTIA and minor stroke: experience at aregional neurovascular clinic. QJM:Monthly Journal of the Association ofPhysicians. 90, 12, 759-763.

Mazzaglia G, Britton AR, Altmann DR,Chenet L (2001) Exploring therelationship between alcohol consumptionand non-fatal or fatal stroke: a systematicreview. Addiction. 96, 12, 1734-1756.

National Audit Office (2005)Department of Health. Reducing Brain

Damage: Faster Access to Better StrokeCare. The Stationery Office, London.

National Collaborating Centre forChronic Conditions (2006)Hypertension: Management ofHypertension in Adults in Primary Care(partial update). Royal College ofPhysicians, London.

National Institute for ClinicalExcellence (2005) Clopidogrel andModified Release Dipyridamole in thePrevention of Occlusive Vascular Events.Technology Appraisal 90. NICE, London.

Ness AR, Powles JW (1999) The role ofdiet, fruit and vegetables and antioxidantsin the aetiology of stroke. Journal ofCardiovascular Risk. 6, 4, 229-234.

North American Symptomatic CarotidEndarterectomy Trial Collaborators(1998) Benefit of carotid endarterectomyin patients with symptomatic moderateor severe stenosis. New England Journalof Medicine. 339, 20, 1415-1425.

Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Giles MF et alfor the Oxford Vascular Study (2004)Change in stroke incidence, mortality,case-fatality, severity, and risk factors inOxfordshire, UK from 1981 to 2004(Oxford Vascular Study). The Lancet. 363,9425, 1925-1933.

Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Flossmann E etal (2005) A simple score (ABCD) toidentify individuals at high early risk ofstroke after transient ischaemic attack.

The Lancet. 366, 9479, 29-36.

Royal College of Physicians (2004)National Clinical Guidelines for Stroke.Second edition. Prepared by theIntercollegiate Stroke Working Party.RCP, London.

Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG,Whincup PH, Walker M (1995) Smokingcessation and the risk of stroke in middle-aged men. Journal of the AmericanMedical Association. 274, 2, 155-160.

Wardlaw JM, Keir SL, Dennis MS(2003) The impact of delays incomputed tomography of the brain on theaccuracy of diagnosis and subsequentmanagement in patients with minorstroke. Journal of Neurology,Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 74, 1, 77-81.

Warlow CP, Dennis MS, Van Gijn J et al (Eds) (2001) Stroke: APractical Guide to Management. Secondedition. Blackwell, Oxford.

Williams B, Poulter NR, Brown MJ etal (2004) British Hypertension Societyguidelines for hypertension management(BHS IV): summary. British MedicalJournal. 328, 7440, 634-640.

Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S et al (2005) Obesity and the risk ofmyocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. The Lancet. 366, 9497,1640-1649.

p50-57w14-16 7/12/06 11:07 am Page 57

/ColorImageDict > /JPEG2000ColorACSImageDict > /JPEG2000ColorImageDict > /AntiAliasGrayImages false /DownsampleGrayImages true /GrayImageDownsampleType /Bicubic /GrayImageResolution 300 /GrayImageDepth -1 /GrayImageDownsampleThreshold 1.00000 /EncodeGrayImages true /GrayImageFilter /DCTEncode /AutoFilterGrayImages true /GrayImageAutoFilterStrategy /JPEG /GrayACSImageDict > /GrayImageDict > /JPEG2000GrayACSImageDict > /JPEG2000GrayImageDict > /AntiAliasMonoImages false /DownsampleMonoImages true /MonoImageDownsampleType /Bicubic /MonoImageResolution 1200 /MonoImageDepth -1 /MonoImageDownsampleThreshold 1.50000 /EncodeMonoImages true /MonoImageFilter /CCITTFaxEncode /MonoImageDict > /AllowPSXObjects false /PDFX1aCheck true /PDFX3Check false /PDFXCompliantPDFOnly false /PDFXNoTrimBoxError true /PDFXTrimBoxToMediaBoxOffset [ 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 ] /PDFXSetBleedBoxToMediaBox true /PDFXBleedBoxToTrimBoxOffset [ 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 0.00000 ] /PDFXOutputIntentProfile (Euroscale Coated v2) /PDFXOutputCondition () /PDFXRegistryName (http://www.stephensandgeorge.co.uk/pdfportal.html) /PDFXTrapped /False

/Description >>> setdistillerparams> setpagedevice