Tokugawa Japan The Unification of Japan

-

Upload

myra-boone -

Category

Documents

-

view

86 -

download

8

description

Transcript of Tokugawa Japan The Unification of Japan

Tokugawa JapanThe Unification of Japan

1600-1867

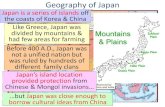

Background•12th – 16th Century

•A shogun (military governor) ruled Japan through retainers who received political rights and large estates in return for military services.

•After the 14th century, the ambitions of shoguns and retainers led to a series of civil wars in the 16th century.

•Japanese historians refer to the 16th century as the era of sengoku, “the country at war.”

Tokugawa Japan•Toward the end of the 16th century, powerful states emerged in several regions of Japan.

•A series of military leaders brought about the unification of the land.

•In 1600 the last of the leaders, Tokugawa Ieyasu, established a military government, the “Tokugawa bakufu” (tent government).

•Ieyasu and his descendants ruled the bakufu as shoguns from 1600 until the end of the Tokugawa dynasty in 1867.

Shoguns •The purpose of the Tokugawa shoguns was to keep their regions calm and prevent the return of civil war.

•The shoguns controlled the daimyo (great names) who were powerful territorial lords who ruled most of Japan from their vast landholdings.

•The 260 or so daimyo functioned as near absolute rulers within their domains.

The Country at War•Each daimyo maintained a government staff by military subordinates that were supported by judiciary, schools, and paper money.

•Many daimyo established relationships with European mariners from whom they learned how to manufacture and use gunpowder weapons.

•During the last decades of the sengoku era, cannons and personal firearms were significant in Japanese conflicts.

Controlling the Daimyo

•From the castle of Edo, modern-day Tokyo, the shogun governed his own domain and tried to control the daimyo in their territories.

•The shoguns instituted “alternate attendance,” which required daimyo to spend every other year in Edo at the Tokugawa court.

•This was intended to keep an eye on the daimyo and encourage them to spend their money and lavish homes and lives in Edo rather than building armies.

Control of Foreign Relations

•The shogun closely controlled relations between Japan and the outside world.

•They knew that Spanish forces had conquered the Philippine Islands in the 16th century.

•They feared that Europeans might cause serious problems by making alliances with daimyo and supplying them with weapons.

Control of Foreign Relations During the 1630’s, the shoguns:

• forbade Japanese from going abroad,

• prohibited the construction of large ships,

• expelled Europeans from Japan,

• prohibited foreign merchants from trading in Japanese ports,

• controlled trade with Asian lands,

• permitted small numbers of Chinese and Dutch merchants to trade in Nagasaki.

Control of Foreign Relations

During the Tokugawa period, Japan carried on a flourishing trade with China, Korea, Taiwan, and the Ryukyu Islands.

Dutch merchants brought news of European and larger world affairs.

Social and Economic Change

• Increased agricultural production

• New crop strains• New methods of water control

and irrigation• Use of fertilize increased rice

yields• Production of cotton, silk,

indigo, and sake increased.• Move from subsistence

farming to market production.

Social Changes• During the 17th century, Japan witnessed dramatic population growth.

• However, in order to raise their standard of living, many families between 1700 and 1850, practiced contraception, late marriage, abortion, and infanticide (“thinning out the rice shoots”).

• This practice, which occurred mostly in rural communities with strained resources, resulted in moderate population gains.

Confucian Social Hierarchy

• Ruling Elites• Shogun• Daimyo• Samurai

• Peasants and Artisans

• Merchants

Social Changes

• Once Japan was stable, Tokugawa authorities pushed daimyo and samurai to become bureaucrats and government officials.

• As they lost their place in society, many of the ruling elite fell into financial difficulty.

• Their principal income came from rice collected from peasant cultivators.

• Many of them fell into poverty.• Merchants in Japan became increasingly wealthy and

prominent.• Japanese cities flourished.• Rice dealers, pawnbrokers and merchants soon controlled

more wealth than the ruling elites.

Cultural Influences of China

• The influence of China continued.

• Formal education began with the study of Chinese language and literature.

• In the late 19th century, Japanese scholars wrote philosophical, religious, and legal works in Chinese.

• The common people embraced Buddhism.

• Confucianism was the most influential philosophical system.

Neo-Confucianism• Traditional Confucian values

such as filial piety and loyalty to superiors was emphasized.

• All those who had formal education (sons of merchants and government officials) received constant exposure to neo-Confucian values.

• By the early 18th century, neo-Confucianism had become the official ideology of the Tokugawa bakufu.

Native Japanese Tradition • During the 18th century,

scholars of “native learning” scorned neo-Confucianism and even Buddhism.

• They emphasized folk traditions, Japanese literature, and the indigenous Shinto religion.

• Many scholars viewed Japanese people as superior to others (xenophobic).

Popular Culture • During the 17th and 18th centuries, a lively middle class emerged out of the merchant class.

• “Floating Worlds,” entertainment quarters with teahouses, theaters, brothels and public baths offered escape from social responsibilities.

• Prose fiction, kabuki theater (bawdy skits), and bunraku (puppet theater) attracted many audiences.

Christian Missions

• In 1549, the Jesuit Francis Xavier traveled to Japan and opened a mission.

• Several powerful daimyo adopted Christianity and ordered their subjects to do so.

• By the 1580’s about 150,000 Japanese had converted to Christianity.

• Tokugawa shoguns restricted European access to Japan for fear Christianity might allow for alliances between daimyo and Europeans.

• Buddhist and Confucian scholars resented Christian conviction that their faith was the only true faith.

• Christian converts became frustrated that they could not become priests or play leadership roles in the missions.

Anti-Christian Campaign

• In 1612, shoguns began rigorous enforcement of decrees putting a halt to Christian missions.

• They tortured and executed European missionaries who refused to leave as well as Japanese Christians who refused to abandon their faith.

• They often executed victims by crucifixion or burning at the stake.

• By the late 17th century, the anti-Christian campaign had claimed tens of thousands of lives.

Dutch Learning

• After 1639, Dutch merchants became the principal source of information about Europe and the world beyond the east.

• A small number of Japanese scholars learned Dutch in order to communicate with the foreigners.

• After 1720, Tokugawa authorities lifted the ban on foreign books and Dutch learning began to play a significant role in Japanese life.

• European art influenced Japanese scholars interested in anatomy, astronomy, and botany.