Tillamook County - 20180612 Visioning p. 2 · 2020-01-31 · Prepared by Innovative Growth...

Transcript of Tillamook County - 20180612 Visioning p. 2 · 2020-01-31 · Prepared by Innovative Growth...

Tillamook County Solid Waste Financial Visioning Committee

DRAFT Agenda for Meeting on June 12, 2018

Time Item Lead Notes

10:00 – 10:20 Introductions, Meeting

Objectives, Warmup

IGS ‐ Jeanne

10:20 – 11:00 Review committee

objectives

IGS – Jeanne Review objectives (see below)

Prioritize among competing

objectives

11:00 – 12:00 Review Draft Report and

Analysis of Options

IGS – Gary Present options

Q&A

12:00 – 12:30 Break / Lunch Lunch brought in

Brief break, then “working lunch”

12:30 – 1:15 Triage Options IGS – Jeanne Which of the 9 options are truly

viable? Which aren’t?

Rate how each contributes to each

goal (H M L)

1:15 – 2:30 Assemble Package(s) IGS – Jeanne Short term

Future/long term strategies

2:30 – 3:00 Recommendations and

next steps

IGS – Jeanne Decide on recommendation of

package(s) to SWAC

CommitteeObjectives: Achieve long‐term financial viability of Tillamook Solid Waste (target $#?)

Make self‐hauling at transfer stations financially self‐sufficient.

Address recycling crisis.

o Recyclables out of MSW stream

o Secondary markets collapsing

While: Encourage responsible waste disposal practices

Ensure equitable delivery of solid waste services.

o Recyclables out of MSW stream

o Secondary markets collapsing

20180612 Visioning p. 1

20180612 Visioning p. 2

ResearchandPreliminaryFindingsonSustainableFundingOptions

forTillamookCountySolidWaste

Prepared by

Innovative Growth Solutions

Revised May 15, 2018

On behalf of

Tillamook County Solid Waste Financial Visioning Committee

20180612 Visioning p. 3

ContentsExecutive Summary ..................................................................................................................... 1

Problem and Background............................................................................................................ 4

Option 1: Raise tipping fees and minimums on self‐haulers ...................................................... 6

Option 2: Countywide self‐haul recycling fee with minimum and per‐ton fee at a rate less

than garbage ............................................................................................................................. 10

Option 3: Opt‐out recycling for all curbside garbage customers ............................................. 13

Option 4: Mandatory curbside garbage service ....................................................................... 17

Option 5: County‐wide levy to pay for services provided by Service District .......................... 20

Option 6: Increase franchise hauler tipping fees ...................................................................... 24

Option 7: Localized improvement districts centered around satellite transfer stations with

fallback option of mandatory service ....................................................................................... 27

Option 8: Raise Solid Waste Fee, indexed to inflation ............................................................. 34

Option 9: “Share the wealth, share the pain” recycling co‐op ................................................. 37

Conclusions and Next Steps ...................................................................................................... 42

20180612 Visioning p. 4

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 1 of 45 December 12, 2017

ExecutiveSummary

The Tillamook County Department of Solid Waste formed a volunteer Financial Visioning

Committee in 2017 to identify ways to ensure the long‐term financial viability of its solid waste

program, address a looming recycling crisis, make its two satellite transfer stations financially

viable, while encouraging responsible waste disposal practices and ensuring equitable service

delivery throughout the County. The committee identified nine options for further investigation

and retained the services of Innovative Growth Solutions to research and analyze each option.

This report contains the results of that research, summarized in the table below.

Summary of Options

Objectives

Options

Financially sustainable

Self‐sufficient Transfer Stations

Address recycling crisis

Encourages responsible

waste disposal

Equitable delivery of services

1. Raise self‐haul tipping fees

Contributes Achieves N/A Contributes Geographic: + Economic: ‐

2. Self‐haul recycling fee

Contributes Contributes Contributes Negative Negative (economic)

3. Opt‐out curbside recycling

Contributes Contributes Contributes Contributes Geographic: + Economic : ‐

4. Mandatory curbside garbage service

Contributes Negative impact

N/A Contributes Possibly contributes (economic)

5. County‐wide levy

Achieves Negative impact

N/A Mixed Uneven impacts

6. Raise franchise hauler tipping fees

Achieves No impact N/A Negligible impact

Neutral or negative

7. Create North & South LIDs

Achieves Achieves N/A Mixed Shifts costs to LID residents

8. Raise Solid Waste Fee

Achieves N/A N/A N/A Negative (economic)

9. Recycling Co‐op Contributes Depends Achieves Contributes Maintains geographic equity

As the analysis shows, none of the options serve all five objectives. All of the options contribute

to the long‐term financial sustainability of the Tillamook County Solid Waste program. Of the

nine options, only two contribute to resolving at least four objectives — opt‐out curbside

recycling, and the recycling co‐op – and neither resolves the financial sustainability goal on its

own.

20180612 Visioning p. 5

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 2 of 45 December 12, 2017

FinancialSustainability

Only four options – a county‐wide levy, raising franchise hauler tipping fees, creating North and

South LIDs, and raising the solid waste fee — achieve the goal of financial sustainability on their

own. All have mixed or negative impacts on progress toward other goals. Raising the solid

waste fee has the least significant negative impacts on other goals, but may not be legally

feasible. Raising franchise hauler tipping fees has similarly limited negative impacts on other

goals but without the legal limitation.

Self‐sufficienttransferstations

Two options – raising self‐haul tipping fees and the LID option – achieve self‐sustainability for

the satellite transfer stations. The self‐haul recycling fee and opt‐out curbside recycling (with a

fee for self‐haul disposal) contribute to transfer stations’ financial sustainability. Mandatory

curbside service and a county‐wide garbage levy actually make financial matters worse for the

satellites.

Encouragingresponsiblewastedisposal

Most of the options have either a positive or mixed/neutral impact on individual waste disposal

practices. Only the self‐haul recycling fee actively disincentivizes responsible behavior.

Recycling

Only three options–establishing a self‐hauler recycling fee, opt‐out curbside recycling, and

creating a new recycling co‐op—address either part of the recycling crisis (separation from the

waste stream and decline of secondary markets).

EquitableDeliveryofServices

Most of the nine options have a mixed or negative impact on equitable delivery of services.

Seven of the nine options either reduce equitable delivery of services or have mixed impacts.

Only two–mandatory curbside garbage service and the recycling co‐op–clearly contribute to

equity.

Conclusion

It is likely that the County will need to pursue a combination of options, including at least one

of the three that resolves the recycling crisis along with one or more of the other six that

contributes more heavily to the program’s long‐term financial sustainability.

The other option is to reconsider or reprioritize the five goals identified by the committee and

consider the implications of the nine options accordingly.

20180612 Visioning p. 6

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 3 of 45 December 12, 2017

These options will now be evaluated by the Financial Visioning Committee and a few options

selected for further analysis leading to a recommendation to the County Commission for

implementation.

20180612 Visioning p. 7

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 4 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

ProblemandBackground

The Tillamook County Department of Solid Waste faces an issue familiar to many public solid

waste utilities in the U.S.:

Rising costs of handling, transportation, and disposal of municipal solid wastes

Due to the lack of a county‐wide recycling program, recycling rates are low, so a

significant amount of recyclable materials end up in the waste disposal stream

Revenues do not keep up with the pace of steadily increasing costs

Increasing demand for services and options for disposal of solid waste and recycling

materials

Slumping demand (and revenue recovery) for recycled materials, particularly plastics on

the international market, which has served as an important recycling outlet for the west

coast

Other issues are more local in nature.

Solid waste disposal limitations. Federal regulations prohibit landfills in coastal areas,

meaning disposal of solid waste must be transported by truck to inland landfills. Closed

landfills operated prior to enactment of those regulations cost the county approximately

$300,000 per year, most of which is paid for by a $1 per month solid waste fee applied

to each developed property, enacted in 1985. The fee has not been raised since its initial

enactment.

Satellite transfer station subsidies. Due to Tillamook County’s history, coastal

geography, and demographics (pop. 26,143), five private haulers operate curbside solid

waste collection franchises in the county. In addition, to improve service and

convenience to local residents and businesses and to encourage responsible disposal

practices, Tillamook County operates three self‐haul stations – one at Tillamook City,

one in Pacific City, and one in Manzanita. These stations also provide the opportunity

for locals to recycle, since Tillamook County’s five private haulers do not provide

curbside recycling services. The Tillamook station also serves franchise haulers and

serves as the collection facility for waste hauled to the satellite stations. The transfer

stations, particularly Manzanita and Pacific City, do not raise sufficient funds to pay for

all operating expenses, requiring a net subsidy of $14,476 in FY2017.

To address these issues, Tillamook County formed a volunteer Financial Visioning Committee

consisting of industry and community leaders to address the following goals:

Achieve long term financial stability of Tillamook Solid Waste

Make self‐hauling at transfer stations financially self‐sufficient.

20180612 Visioning p. 8

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 5 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Encourage responsible waste disposal practices by all in the community (recycle, dispose

locally or at curb, etc.) in the best interest of public health

Address recycling crisis

Ensure equitable delivery of solid waste services

The County retained Innovative Growth Solutions of Oregon City, OR to lead the research effort

and facilitate committee deliberations.

The committee met in October, 2017 and adopted a research agenda to investigate the

following possible solutions:

Raise tipping fees and minimums on self‐haulers

County‐wide recycling fee with minimum and per‐ton fee at a rate less than garbage

Mandatory curbside recycling and garbage

County‐wide solid waste service district with levy to pay for service

Increase franchise hauler tipping fees

Localized improvement districts centered around satellite transfer stations with fallback

option of mandatory service

Raise Solid Waste Fee, indexed to inflation

A “Share the wealth, share the pain” recycling co‐op (as part of or independent of

mandatory service)

Upon further research and in consultation with the Tillamook County Manager of Solid Waste

Services on November 30, 2017, it was determined that the option of “Mandatory curbside

recycling and garbage” needed to be subdivided into two separate options for analysis:

Opt‐out curbside recycling for all current garbage service customers

Mandatory curbside garbage service for all households

This document examines the issues specific to each option on the research agenda, outlines the

approach and methodology taken to analyze the option, and summarizes the results. These

results will be used by the Financial Visioning Committee to evaluate the options and make

recommendations to the Tillamook County Commission for further action.

20180612 Visioning p. 9

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 6 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Option1:Raisetippingfeesandminimumsonself‐haulers

Description: Raise the minimum and per‐tonnage fees on self‐hauler loads at the three transfer

stations in Tillamook County.

Background: As Table 1‐1 below shows, self‐haul loads at transfer stations accounted for nearly

8.5 tons of municipal solid waste (MSW) and 20,681 transactions at Tillamook Transfer Station

(TTS) in FY2016‐17, up 8% in tonnage but down 3.6% in transactions from FY2015‐16. This

resulted in a revenue increase of $60,320 at TTS, and an additional $229,232 in revenue at

Manzanita Transfer Station (MTS) & and Pacific City Transfer Station (PCTS), but required a

subsidy of approximately $14,476 in FY2016‐17 to cover costs.

Table 1‐1: Self‐haul MSW (tons) per Transfer Station, Tillamook County

MSW tons FY2013 FY2014 FY2015 FY2016 FY2017

MTS 456 428 736 1,001 1,153

PCTS 52 47 66 128 209

TTS SH 6,499 5,953 6,386 6,639 7,122

Self‐haul tons 7,006 6,428 7,188 7,768 8,483

Current rates for self‐haulers are given in Table 1‐2. Note that MSW rates were increased at

Tillamook in 2017 from $93 per ton, and at all locations from $92, $105, and $105, respectively.

Tillamook’s tipping fees are comparable to other counties in the area.

Table 1‐2: Self‐hauler Tipping Fees (per ton)

Transfer Station

Garbage/ Municipal SW

Yard Debris

Asphalt/ Roofing

Minimum Fee (effective

7/1/17)

Tillamook $94.86 $80.00 $75.00 $19.00

Pacific City $110.00 $90.00 $85.00 $8.50

Manzanita $110.00 $90.00 $85.00 $7.50

ProsandCons

Pros Cons

Increases revenue as expenses increase

May increase Franchise hauler revenue base by discouraging some self‐hauler trips

County has existing legal authority to implement the change

Possible adverse public reaction

Possible increase in illegal dumping

Possible shift from satellites transfer stations back to central for self‐haulers and/or contractors

20180612 Visioning p. 10

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 7 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Analysis

Per‐tonFees

A one dollar ($1.00, approximately 1%) per ton increase in tipping fees, applied to the

estimated 8,483 annual tons of self‐hauled MSW at all three transfer stations, would yield a

combined $8,483 in increased revenue at the transfer stations. Of that amount, $1,153 would

be raised at MTS and $209 at PCTS. This amount would cover about 59% of the amount of

subsidy required to cover costs at all transfer stations. The increase required to cover the full

amount, assuming constant (2016‐17) tonnages and no increase in minimum fees, would be

$1.71 per ton (about 1.7%).

However, self‐haul MSW tonnages are not consistent year‐to‐year. Self‐hauled tonnages

increased 9% across all transfer stations from 2015‐16 to 2016‐17. In other years, tonnages

have dipped as much as 5%. Table 1‐3 shows the tipping fee increase that would be needed in

each of those scenarios.

Table 1‐3 Cost/ton increase required to raise $14,476

(no minimum fee change)

TTS PCTS MTS

Current fees $94.86 $110.00 $110.00

Assuming no MSW growth

$1.71 $96.57 $111.71 $111.71

With 9% MSW growth

$1.58 $96.44 $111.58 $111.58

With 5% MSW decrease

$1.80 $96.66 $111.80 $111.80

This assumes that the increased revenue collected at TTS would continue to be used to help

defray costs at the PCTS and MTS locations. Note that TTS collects 84% of self‐hauled MSW. If

each location were required to raise the funds through tipping fees collected solely at that site,

the resulting increase in tipping fees would be $23.10 (22%) per ton at PCTS and $8.37 (8%) per

ton at MTS, raising rates to $133.10 and $118.37 per ton, respectively (assuming constant 2016‐

17 MSW tonnages).

MinimumFees

The foregoing analysis assumes no increase in minimum fees. A minimum fee increase of 1.1%

(corresponding to a $1 increase in per‐ton tipping fees at Tillamook Transfer Station) would

20180612 Visioning p. 11

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 8 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

generate an additional $2,624 in revenue. That would defray about 12.7% of the $14,476

subsidy.

If the desire were to cover the subsidy solely through minimum fees, the minimum fee would

need to increase about 5.5%, as shown in Table 1‐4.

Table 1‐4 Estimated Revenue from Minimum Fee Increases

2016‐17 Total

Transactions

Min Fee Trans.

Min. Fee

MF w/1.1% increase

Revenue increase

MF w/5.5% Increase

Revenue Increase

MF if no increase at TTS

Revenue increase

TTS* 20,681 9,100 $19.00 $19.20 $1,823 $20.10 $10,054 $19.00 $0

PCTS 2,888 2,195 $8.50 $8.59 $197 $8.99 $1,085 $9.50 $2,293

MTS 10,341 7,652 $7.50 $7.58 $605 $7/94 $3,337 $9.00 $11,525

* Estimated $2,624 $14,476 $13,818

Note that TTS minimum fees are over twice that of PCTS and MTS. The final pair of shaded

columns shows an alternative scenario, under which minimum fees would be increased at MTS

to $9.00 and to $9.50 at PCTS, and kept constant at TTS. Notice that this scenario generates

nearly all of the revenue needed to eliminate the subsidy.

It could be argued that the revenue potential of these minimum fees would not be realized if

self‐haulers reduced the number of minimum‐fee trips in reaction to the price increases. While

possible, recent data shows that minimum fee trips did not decrease with similar price

increases over the past two years. We therefore expect similar trends to continue into the

future.

Proportional increase in Per‐ton and Minimum Fees

Across the three transfer stations, minimum‐fee trips account for approximately 56% of self‐

hauler tipping fee revenue. Increasing the minimum fee proportionately with the per‐ton

tipping fee to cover the $14,476 subsidy would require a 1.6% increase in both tipping fees and

minimum fees, yielding the fee structure shown in Table 1‐5.

Table 1‐5: Self‐hauler Tipping Fees with 1.6% increase

Transfer Station

Garbage/ Municipal SW

Yard Debris

Asphalt/ Roofing

Minimum Fee (effective

7/1/17)

Tillamook $96.28 $80.00 $75.00 $19.29

Pacific City $111.65 $90.00 $85.00 $8.63

Manzanita $111.65 $90.00 $85.00 $7.61

20180612 Visioning p. 12

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 9 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Table 1‐6: Evaluation of Option 1, Raise Self‐hauler Tipping Fee

Objective Evaluation

Achieve long term financial stability of Tillamook Solid Waste

Contributes to goal

Make self‐hauling at transfer stations financially self‐sufficient.

Achieves goal with sufficient increase

Encourage responsible waste disposal practices by all in the community (recycle, dispose locally or at curb, etc.) in the best interest of public health

Contributes to goal

Address recycling crisis Does not address goal

Ensure equitable delivery of solid waste services Maintains geographic access, reduces economic equity

Conclusions

Raising per‐ton tipping fees by less than 2% would eliminate the subsidy (achieve

financial self‐sustainability at the satellites) from the county to transfer stations if all of

the increased revenue were applied to the subsidy amount, regardless of collection site.

If each station were required to eliminate its own subsidy via tipping fees, Pacific City

would need to raise rates 22%, and Manzanita 8%. This would widen the gap in fees

between satellites and the central Tillamook station and create an even wider gap

between Pacific City and Tillamook and could incentivize Pacific City area residents to

self‐haul garbage to Tillamook or to dump illegally. This effect would be minimized if the

minimum fees at satellites were kept well below central station minimum fees as

currently structured.

Raising only the minimum fees by 5.5% would also eliminate the subsidy. Raising

minimum fees at Manzanita by $1.50 to $9.00 and at Pacific City by $1.00 to $9.50

would very nearly eliminate the subsidy.

Raising all rates and minimums 1.5% would eliminate the subsidy.

Any increase in rates would contribute toward long‐term financial sustainability of the

solid waste program in Tillamook County.

20180612 Visioning p. 13

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 10 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Option2:Countywideself‐haulrecyclingfeewithminimumandper‐tonfeeataratelessthangarbage

Description: Charge for curbside and self‐haul recycling, with a minimum fee and tonnage fee

similar to but less than the rate for garbage.

Background: The County currently does not have curbside recycling and does not charge for

separated recyclable materials self‐hauled to transfer stations. The county also has three

unstaffed recycling drop‐off stations for recycling.

Recycling accounts for 7‐8,000 tons of materials disposed of at transfer stations. Self‐haulers

account for nearly 90% of recyclable materials. Franchise haulers also contribute about 10%.

Table 2‐1 shows current recycling and garbage (MSW) quantities from 2014‐2016 by location.

Table 2‐1 MSW Quantities in Tillamook County

Franchise MTS PCTS TTS SH Other Total

Recycling 2014 798 944 126 5,356 1,940 9,164

MSW 2014 14,068 517 55 7,522 997 21,590

Recycling 2015 819 1,166 122 4,857 2,441 9,405

MSW 2015 15,453 919 89 7,103 283 23,130

Recycling 2016 778 1,284 201 4,809 0 7,072

MSW 2016 16,551 1,083 162 7,655 316 24,751

ProsandCons

Pros Cons

Increases revenue as expenses increase

Pays for service currently provided with no current revenue source

May increase Franchise hauler revenue base by discouraging some self‐hauler trips

Encourages curbside separation of recyclables from MSW ― potential cost savings

Possible adverse public reaction

Possible increase in illegal dumping

Could discourage careful separation of recycling from MSW

Curbside recycling incurs additional costs on self‐haulers

Poten al loss of revenue ― current recyclables disposed of as MSW

Potential discouragement of curbside separation of recyclables if customers don’t see significant cost reduction in recycling

Logistical challenges

Increased operational administration

20180612 Visioning p. 14

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 11 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Analysis

Scenarios were constructed assuming separated, recyclable materials, currently disposed free

of charge, would be assessed tipping fees at 25%, 50%, or 75% of that assessed for self‐hauled

MSW as well as for separated recyclables from haulers. The resulting increased revenue is given

in the table below.

Table 2‐2 Estimated Revenue from Charging for Recycling

at 25‐75% of MSW Tipping Fees

Recycling Tons

$/Ton MSW 25% 40% 50% 75%

TTS 4,809 $94.86 $114,045 $182,473 $228,091 $342,136

MTS/PCTS 1,485 $110.00 $40,838 $65,340 $81,675 $122,513

Haulers 778 $78.27 $15,224 $24,358 $30,447 $45,671

TOTAL $170,106 $272,170 $340,213 $510,319

This assumes no change in current recycling behavior or amounts in response to charging for

recycling, and no curbside recycling program. One would assume that as tipping fees for

recycling approach those of MSW, the incentive for separating and hauling recycling to transfer

stations would decline and would result in greater quantities being intermingled with MSW at

both transfer stations and on curbside pickup.

While the revenue from each of these options appears inviting, one must also consider the

operating and setup costs from initiating this program. In a 2014 study,1 the US EPA outlined

the costs localities would face in establishing a local recycling program. Costs and factors

applied to the Tillamook County situation appear in Table 2‐3, below. Processing facilities are

assumed to be needed at all three transfer stations. We assume middle ground with respect to

the EPA’s estimate of $5,000‐$10,000 in other equipment. We also assume adding one full‐time

employee at each currently unstaffed site.

1 https://www.generalkinematics.com/blog/cost‐starting‐full‐force‐recycling‐program/

20180612 Visioning p. 15

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 12 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Table 2‐3Recycling Program Setup and Operating Costs

Startup Cost

Cost/Unit Units Net

Processing Facilities $10,000 3 $30,000

Equipment $7,500 (Total) $7,500

Total $37,500

Annual Operating Cost

Employees,* Unstaffed Sites

$69,888 3 $209,664

Processing Facility $18,000 3 $54,000

Annual amortization of start‐up costs (10 years,

5% interest)

$4,856

Total $268,520

* Full‐time employees assumed at rate of $16 per hour plus benefits and overhead

As the table shows, recycling tipping fee rates would need to be approximately 40% of the

MSW rate to cover the costs associated with setting up and operating a self‐hauler recycling

program, assuming no change in customer behavior.

Table 2‐4: Evaluation of Option 2, Self‐haul Recycling Fee

Objective Evaluation

Achieve long term financial stability of Tillamook Solid Waste

Contributes to goal

Make self‐hauling at transfer stations financially self‐sufficient.

Contributes to goal

Encourage responsible waste disposal practices by all in the community (recycle, dispose locally or at curb, etc.) in the best interest of public health

May reduce achievement of recycling goal, may reduce curbside disposal

Address recycling crisis Contributes to goal

Ensure equitable delivery of solid waste services Reduces economic equity

Conclusions

Even a nominal (25%) recycling fee would generate substantial revenue to the county.

However, the costs of setting up a recycling program would offset a significant amount

of the expected revenue. A recycling tipping fee of about 40% of the MSW rate would

be required to defray costs of setting up and operating the program.

20180612 Visioning p. 16

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 13 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Option3:Opt‐outrecyclingforallcurbsidegarbagecustomers

Description: All homes that currently have curbside garbage service would automatically get

curbside recycling, unless they opt out. Collection fees would increase to cover the cost of

recycling service.

Background: Currently, curbside recycling is available to a limited number of households

(approximately 250) in the City of Tillamook. Residents and property owners currently self‐haul

the bulk of their recyclables to one of the three transfer stations in the County. In FY2016‐17,

Tillamook County generated over 7,000 tons of recyclables, approximately 22% of all waste

disposal; nearly 90% was from self‐haulers.

Opt‐out programs enjoy far greater participation rates than opt‐in programs. For example, the

City of Newport, Oregon added an opt‐out leaf collection program to their garbage collection

program with a nominal increase in collection fees. Only 5% of residents opted out.

ProsandCons

Pros Cons

Encourages curbside service

Encourages recycling

Reduces self‐hauling trips

Potential reduction of costs at transfer stations

Possible adverse public reaction

Fairness issues – cost differences between cities, rural areas

Administrative costs/complexity

Potential commingling/contamination of MSW into recycling bins

Potential for County revenue loss (reduction of some high‐margin self‐haul minimum fee transactions)

Significant start‐up and operating costs

Analysis

Mandatory curbside recycling would incur substantial start‐up costs and additional ongoing

operating costs, both to haulers and to the county. Startup costs, based on an EPA study2

applied to the Tillamook County situation, are shown in the table below. The table assumes

setting up or enhancing facilities to further process recycled materials, three drop‐off sites in

remote areas for bulk pick‐up, the addition of specialized trucks (one per hauler) with

compartments to keep recycling segregated, and County provision and distribution of curbside

2 https://www.generalkinematics.com/blog/cost‐starting‐full‐force‐recycling‐program/

20180612 Visioning p. 17

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 14 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

collection bins to each single‐family household with a 95% opt‐in rate for current customers.3

The results are shown in Table 3‐1 below.

Table 3‐1Recycling Program Setup and Operating Costs

Startup Cost

Cost/Unit Units Net

Processing Facilities $10,000 3 $30,000

Trucks (1 per co.) $30,415 5 $152,075

Equipment $7,500 1 $7,500

SFHH Curbside collection bins $99 7,262 $718,890

Total $908,465

Annual Operating Cost

Employees,* Unmanned Sites $69,888 3 $209,664

New Franchise Hauler employees $69,888 5 $349,440 Processing Facility $18,000 3 $54,000

Annual amortization of start‐up costs (10 years, 5% interest)

$117,650

Total $730,754

It is assumed that the revenue would be recouped through an increase on curbside pickup fees.

As Table 3‐2 shows, an additional fee of approximately $7.20 per month would be required to

defray the increased costs of the curbside recycling program, based on 2017 levels.

Table 3‐2Estimated Revenue, Curbside Recycling Fee

Hauler Est. Customers, 2017

Est. Rev, $7.20/month recycling fee

NVSS 1,331 $114,963 CSS 2,848 $246,036 RWO 1,739 $150,234 Rsan 2,217 $191,510 OSS* 338 $29,170

TOTAL $731,913

3 Single‐family household estimate based on Census data.

20180612 Visioning p. 18

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 15 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

We could expect some changes in behavior as a result of this initiative that would affect

revenues and costs. We would expect a reduction of self‐hauling trips to transfer stations,

displacing trips to transfer stations generated primarily to dispose of recyclable goods. This

could potentially reduce costs, traffic, and safety concerns at transfer stations. It would also

reduce revenue, particularly from a drop in high‐margin minimum‐fee transactions.

Currently, of the satellite stations, only Pacific City Transfer Station tracks recycling‐only

transaction history. In 2016‐17, recycling‐only transactions accounted for 58% of all

transactions. In two key ways, however, disposal activity at Manzanita Transfer Station is similar

to Pacific City: recycling accounts for about 60% of total tonnage of disposed materials, and

minimum‐fee transactions account for about 3/4 of all transactions. For analytical purposes,

then, we will assume that Manzanita’s recycling‐only trip rate is similar to Pacific City’s. At

Tillamook Transfer Station, recycling tonnages (approximately 40%) are lower and minimum‐fee

transactions accounts (approximately 25%) for a significantly lower proportion of transactions.

Table 3‐3Impact of Recycling Fee on Transfer Station Trips, Revenue, Tons of Recycling

Transfer Station

Red. In Min Fee Trips

Min Fee Rev. loss

Red. in Recycling‐only Trips

Red. in Recycling Tons

Red. in self‐Haul MSW, tons

Red. in self‐haul non‐MF rev.

Total Rev. Loss

Tillamook 1,551 ($29,469) 3,102 2,405 712 ($67,559) ($97,028)

Pacific City 688 ($5,847) 5,466 101 21 ($2,299) ($8,146)

Manzanita 2,305 ($17,287) 5,555 642 115 ($12,683) ($29,970)

4,544 ($52,603) 14,123 3,148 848 ($82,541) ($135,145)

Recovering the loss of this additional revenue would require adding a curbside recycling fee of

approximately $1.30 per month per household in recycling fees, or a total of $8.50 per month,

assuming that other savings do not cover that lost revenue. Table 3‐4 summarizes the revenue

by hauler.

Table 3‐4Estimated Revenue, Curbside Recycling Fee

Hauler Est. Customers, 2017

Est. Rev, $8.50/month recycling fee

NVSS 1,331 $135,720 CSS 2,848 $290,460 RWO 1,739 $177,359 Rsan 2,217 $226,088 OSS* 338 $34,437

TOTAL $132,151

20180612 Visioning p. 19

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 16 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Table 3‐5: Evaluation of Option 3, Opt‐out recycling

Objective Evaluation

Achieve long term financial stability of Tillamook Solid Waste

Contributes to goal

Make self‐hauling at transfer stations financially self‐sufficient.

Contributes to goal

Encourage responsible waste disposal practices by all in the community (recycle, dispose locally or at curb, etc.) in the best interest of public health

Contributes to responsible disposal and recycling

Address recycling crisis Contributes to goal (revenue)

Ensure equitable delivery of solid waste services Reduces economic equity by raising curbside collection rates

Conclusions

Opt‐out curbside recycling would incur substantial start‐up costs and additional ongoing

operating costs, both to haulers and to the county.

A monthly charge of $8.50 per month would be required to cover costs and lost

revenues resulting from the curbside recycling program.

Curbside separation of recyclables would, however, potentially reduce costs at transfer

stations.

PCTS and MTS would incur significant revenue losses due to reduction in minimum‐fee

trips that would need to be recovered through additional subsidies.

20180612 Visioning p. 20

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 17 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Option4:Mandatorycurbsidegarbageservice

Description: Require and charge for curbside collection of garbage at every developed property

in the County.

Background: Currently, 57% of owner‐occupied single‐family homes opt in to curbside garbage

collection in Tillamook County. Properties without curbside service must find alternatives for

garbage disposal (presumably, self‐haul).

ProsandCons

Pros Cons

Encourages curbside service

Encourages recycling

Reduces self‐hauling trips

“Everyone benefits, everyone pays”

More efficient for haulers

Possible adverse public reaction

Fairness issues – cost differences between cities, rural areas

Administrative costs/complexity

Potential for County revenue loss (reduction of high‐margin self‐haul minimum fee transactions)

Analysis

Of the estimated 19,583 developed properties in Tillamook County, approximately 8,2294 have

curbside garbage pickup service. Of the 13,410 estimated owner‐occupied single‐family homes,

an estimated 7,967 have curbside pickup (59%). Mandatory service for all owner‐occupied

single‐family homes would add of an estimated 5,164 service properties in the county. (Service

could also be extended to long‐term rentals; however, data on the numbers of long‐term

rentals is currently unavailable.)

For the purpose of this analysis, it is assumed that the MSW disposed of by these properties

currently goes to transfer stations via self‐haul. We will further assume that mandatory service

would eliminate about 75% of self‐hauling loads at transfer stations, and 90% of minimum‐fee

trips.

The table below summarizes the impact of mandatory curbside garbage collection service on

franchise haulers.

4 Based on complete reports from three haulers (CSS, NVSS, and OSS), partial reporting from RWO, and 2010 figures from R‐San.

20180612 Visioning p. 21

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 18 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Table 4‐1Effects of Mandatory Curbside Garbage Service

New customers and revenue, by Hauler

Hauler 2016‐17 Revenue

New Customers

Add'l MSW (Tons)

32‐gal can Add'l Revenue

NVSS $1,035,046 944 1,203 $32.50 $368,169

CSS $990,654 1,834 3,549 $18.15 $399,445

RWO $364,504 934 937 $26.08 $292,305

Rsan $188,111 1,261 988 $23.50 $355,602

OSS* $93,977 191 86 $28.95 $66,353

TOTAL $2,672,292 5,164 6,763 $1,481,865

Haulers would need to increase their capacity to keep up with the increased demand. The table

below estimates the capacity and cost impacts on each hauler. The table assumes each

company would keep the same ratio trucks‐and drivers to customers ratio as they currently

employ and increase their capacity accordingly.

Table 4‐2 Cost and Capacity impacts on Haulers due to Mandatory Service

Hauler Additional Trucks

Annual Amortized Cost of Trucks

Driver Salary & Benefits

Fuel, Repair & Maint, Insurance

Tipping Fees

County fees

Total

NVSS 2 $7,878 $139,776 $11,000 $81,230 $150 $240,034

CSS 2 $7,878 $139,776 $11,000 $292,437 $150 $451,241

RWO 3 $11,817 $209,664 $16,500 $74,558 $225 $312,763

Rsan 1 $3,939 $69,888 $5,500 $75,785 $75 $155,187

OSS* 0.5 $1,969 $34,944 $2,750 $5,330 $38 $45,031

TOTAL $524,160 $41,250 $529,340 $563 $1,204,256

The following table shows the impact on transfer stations. Self‐haul quantities and revenue

would drop dramatically.

20180612 Visioning p. 22

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 19 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Table 4‐3 Reduction in self‐hauling due to mandatory curbside service

Transfer Station

Current Self‐Haul Transactions

Red. In Min Fee Trips

Min FeeRev. loss

MSW tons, 2016‐17

Est. self‐haul Reduction, tons

Est. Reduction, non‐MF revenue

Total revenue reduction

Tillamook 20,681 (18,613) ($353,645) 7,122 5,342 ($483,077) ($836,722)

Pacific City 2,888 (2,599) ($22,093) 209 157 ($9,584) ($31,677)

Manzanita 10,341 (9,307) ($69,802) 1,153 865 ($64,279) ($134,080)

TOTAL 33,910 (30,519) ($445,540) 8,484 6,363 ($556,939) ($1,002,479)

Table 4‐4: Evaluation of Option 4, Mandatory Curbside Garbage Service

Objective Evaluation

Achieve long term financial stability of Tillamook Solid Waste

Contributes to goal

Make self‐hauling at transfer stations financially self‐sufficient.

Makes satellite transfer stations less viable

Encourage responsible waste disposal practices by all in the community (recycle, dispose locally or at curb, etc.) in the best interest of public health

Contributes to responsible disposal and recycling – increases curbside disposal, reduces transportation impacts

Address recycling crisis Does not directly address goal

Ensure equitable delivery of solid waste services Could improve economic equity if new revenue resulted in lower curbside rates

Conclusions Mandatory curbside garbage service at every household in Tillamook County would

generate approximately $270,000 in additional net revenue to private haulers.

Mandatory curbside garbage service would also reduce self‐haul revenues at transfer

stations by an estimated $1 million, but would increase franchise‐hauler tipping fees by

approximately $530,000, for a net loss of about $470,000 in Transfer Station revenue.

Mandatory curbside service would reduce quantities, revenue, and traffic at the Pacific

City and Manzanita Transfer Stations to unsustainable levels and those stations would

probably need to close. Assuming the remaining self‐haulers would divert trips to

Tillamook, which charges lower fees, this would result in a further revenue reduction of

about $5,000 per year. Closing these stations would reduce costs approximately

$304,000 per year.

On net, the County would face a net revenue reduction of about $170,000. This could be

recovered through fees on the haulers’ increased revenues. If so, this would result in a

net system (haulers plus county) revenue gain of approximately $108,000 per year.

If this revenue gain were applied to service rates, customers would enjoy an average of

approximately $0.67 in decreased fees per property served per month.

20180612 Visioning p. 23

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 20 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Option5:County‐widelevytopayforservicesprovidedbyServiceDistrict

Description: Impose a new levy to pay for garbage service county‐wide (on top of solid waste

fee).

Background: While Tillamook County Solid Waste is already, technically, a service district, the

County does not provide curbside services. Private franchises provide services, charge and

collect fees, and incur collection and disposal expenses. Under this proposal, the County would

collect revenue for services through a county‐wide levy. Delivery would continue to be

delivered via private haulers by contract in specific service areas.

Currently, the County currently charges a $1 monthly fee per developed property for solid

waste services, collected on the property tax bill. The revenue accrues directly to the County.

Measure 5/97 restrictions limit the County’s ability to adjust this fee, which has not risen since

1985, resulting in a 57% reduction in purchasing power. In addition, customers of franchise

haulers pay monthly garbage collection fees, which are adjusted periodically for inflation.

Establishing a new service district with new, chartered authority may provide legal flexibility to

charge new per‐household or per‐property fees to pay for garbage service in lieu of either or

both of these fees. However, opponents of this approach may challenge the county’s ability to

establish a new entity with authority not already vested in the county’s existing service district.

Further research on the legalities involved is required. The analysis that follows assumes that

the county does have the requisite authority to establish such a district.

ProsandCons

Pros Cons

High revenue potential

Overcomes Measure 5/97 limitation on Solid Waste Fee

Possible adverse public reaction

Possible legal challenges to County’s authority to implement this change

Impact on Pay‐as‐you‐throw system

Analysis

It is assumed for the sake of this analysis that the cost of administering solid waste services

under a new Service District would be the same as those incurred currently under the current

framework, with five franchise haulers and a central governing body (Tillamook County Solid

Waste). No changes in operations are anticipated. We estimate that there would be a one‐time

additional cost of transitioning to the new District of approximately $98,000, primarily for

public education, at about $5 per developed property (19,583), amortized over a ten‐year

period ($9,800 per year).

20180612 Visioning p. 24

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 21 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

There are an estimated 19,583 developed properties in the County, yielding approximately

$235,000 annually in solid waste fees. According to submitted reports, franchise haulers

collected $2,672,292 in service fees from customers in FY2017. This yields a break‐even annual

revenue target of $2,907,292 for a solid waste service district levy. We anticipate that this

amount would increase 3% annually, corresponding to the annual increases in property taxes

under Measures 5 and 97.

A levy would be attached to the property tax bill. Currently, Tillamook County collects about

$6,600,000 in property taxes annually. The levy required to raise $2.9 million would be $3.20

per $1,000 of assessed property value.

The resulting levy amounts on various “typical” properties in the county are given in the table

below. The final column shows the change (increase or decrease) in what the profiled property

would pay annually with a levy vs. current fees. Note that levies, unlike solid waste fees, apply

to undeveloped lots.

Table 5‐1. Estimated Service District levy amounts for “typical” properties in Tillamook County

Property description

Real Market Value

2017 Assessed Value

Est. 2017 Prop. Tax

2018 Avg Annual

pickup fees

Solid Waste Fee

Total Annual Levy at

2017 AV*

Change in SW Charges

1500 sq.ft. 3 BR

home $325,000 $191,000 $1,381 $275 $12 $1,668 $610 + $323

Tillamook 2,200

sq ft retail $565,000 $332,000 $2,400 $1,318 $12 $3,730 $1,061 ($269)

1,700 ft

Commercial/

Industrial

$349,900 $206,000 $1,489 $1,318 $12 $2,819 $658 ($671)

2,800 sq ft

restaurant $640,000 $376,000 $2,718 $2,308 $12 $5,038 $1,202 ($1,118)

Big box retail

(25,000 sf) $1,200,000 $705,000 $5,097 $3,494 $12 $8,603 $2,253 ($1,254)

30‐40 unit apt.

building $2,700,000 $1,586,250 $11,469 $3,494 $12 $14,975 $5,069 + $1,563

Med sized hotel $3,900,000 $2,291,250 $16,566 $3,494

$12 $20,073 $7,322 + $3,815

Empty

undeveloped lot $70,000 $41,125 $362 $0 $0 $362 $131 + $131

Table 5‐2 shows the increase in total property taxes, including the new levy, for each

hypothetical property over the coming decade.

20180612 Visioning p. 25

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 22 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Table 5‐2. Estimated Service District property tax increases for “typical” properties in Tillamook County

Property description Real Market Value

2017 Assessed Value

Est. 2017 Prop. Tax + Levy

Est. 2022 Prop. Tax + Levy

Est. 2027 Prop. Tax + Levy

1500 sq.ft. 3 BR home $325,000 $191,000 $1,991 $2,309 $2,676

Tillamook 2,200 sq ft retail

$565,000 $332,000 $3,461 $4,000 $4,639

1,700 ft Commercial/Ind. $349,900 $206,000 $2,147 $2,477 $2,874

2,800 sq ft restaurant $640,000 $376,000 $3,920 $4,532 $5,256

Big box retail (25,000 sf) $1,200,000 $705,000 $7,350 $8,508 $9,866

30‐40 unit apartment building

$2,700,000 $1,586,250 $16,538 $19,160 $22,214

Med sized hotel $3,900,000 $2,291,250 $23,888 $27,681 $32,092

Empty undeveloped lot $70,000 $41,125 $493 $572 $663

Table 5‐3 shows the annual revenue collected by the levy, in lieu of solid waste fees and

curbside collection fees.

Table 5‐3 Annual Levy Revenue

Year Revenue

2017 $2,917,092

2020 $3,187,585

2022 $3,381,709

2027 $3,920,327

Table 5‐4: Evaluation of Option 5, County‐wide Levy for Garbage Service

Objective Evaluation

Achieve long term financial stability of Tillamook Solid Waste

Achieves goal

Make self‐hauling at transfer stations financially self‐sufficient.

Makes goal more difficult to achieve—transfer stations become less utilized by self‐haulers

Encourage responsible waste disposal practices by all in the community (recycle, dispose locally or at curb, etc.) in the best interest of public health

Increases curbside disposal, reduces transportation impacts, reduces illegal dumping, disincentivizes curbside separation

Address recycling crisis Does not directly address goal

Ensure equitable delivery of solid waste services Shifts costs from homeowners and small property owners to owners of undeveloped land

20180612 Visioning p. 26

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 23 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Conclusions

A solid waste levy would raise a steadily increasing flow of revenue to the solid waste

collection and disposal system (3% per year).

Since levies are imposed on all properties, including undeveloped properties, and the

Solid Waste Fee is a flat rate on developed properties only, the levy would shift some of

the costs of solid waste collection onto undeveloped properties.

Since the levy is based on assessed property value rather than intensity of service

required, a solid waste levy would shift some of the costs of solid waste collection and

disposal from owners of small and mid‐sized commercial properties to homeowners,

owners of larger commercial properties, owners of multi‐unit rental properties.

The impact on the pay‐as‐you‐throw fee system is difficult to determine, but a few

conclusions can be clearly drawn:

o Separating charges from use (quantity of waste disposed) would discourage

waste minimization at the curbside and would disincentivize separation of MSW

from recycling.

o Illegal dumping would be discouraged, as it would cost the property owner no

more to leave garbage on the curb as to illegally dump it.

o Self‐haul to transfer stations would be disincentivized, for similar reasons.

Transfer stations would gradually become depots for garbage unsuitable for

curbside pickup (large items, hazmat, etc.).

20180612 Visioning p. 27

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 24 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Option6:Increasefranchisehaulertippingfees

Description: Raise the per‐tonnage fees on franchise loads at Tillamook Transfer Station.

Background: Franchise hauler loads at Tillamook Transfer Station accounted for 16,848 tons

and 4,095 transactions in 2016, up from 16,114 tons and 3,898 transactions in 2015. See Table

6‐1. This resulted in $1,297,973 in total revenue. Franchise haulers’ fee schedule is given in

Table 6‐2, below.

Table 6‐1: Margin on Franchise Hauler MSW

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Margin on Fr/ton 14.46 13.69 12.91 14.84 16.79

Margin on SH/ton 27.46 26.69 30.41 34.41 33.06

Table 6‐2: Franchise hauler Fees

Material Rate (effective 7/1/17)

Garbage/ Municipal SW

$78.27 Per ton Yard Debris $70.00

Asphalt/ Roofing $65

Franchise Fee$75

Per truck

ProsandCons

Pros Cons

Increases revenue as expenses increase

County has existing legal authority to implement the change

If accompanied by self‐hauler increase, likely perceived as “fair”

Haulers likely to oppose

Costs likely passed on to customers / increases curbside rates

To extent costs absorbed by haulers, could threaten viability of those businesses

Analysis

The current hauler tipping rate of $78.27 per ton is projected to raise approximately $1,365,000

in revenue in 2017 at current estimated tipping volumes. However, the tonnage of municipal

waste disposed in the county has increased, on average, 5.4% annually in recent years.

Projecting that annual rate of growth yields revenue estimates given in Table 6‐3, below. As the

20180612 Visioning p. 28

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 25 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

table shows, continued increases at that rate would generate an increase in MSW tonnage and

tipping fee revenue of nearly 70% over the next ten years.

One would assume that costs would increase at a similar rate over that period. In order to

generate additional revenue to cover costs, tipping rates would need to increase. Table 6‐3 also

shows the impact of a $1 per year increase in franchise hauler tipping fees over the next ten

years, assuming the same 5.4% annual growth. As the table shows, by 2027, this increase would

yield approximately an additional $300,000 in revenue to the County.

It is assumed that haulers would defray those costs through collection fee increases. Collection

fees would need to increase approximately 11% by 2027 (approximately 1.1% annually) to

cover those costs, independent of other cost increases. By comparison, hauler collection fees

increased an average of 2% in 2017.

Table 6‐3 Projected Franchise Hauler

MSW Disposal and Tipping Fee Revenue

Tons of MSW Baseline Projected Revenue

Tipping fees per ton

Net Revenue (assuming tipping

fee increases)2017 17,447 $1,365,577 $78.27 $1,365,577

2018 18,391 $1,439,454 $79.27 $1,457,845

2019 19,386 $1,517,329 $80.27 $1,556,101

2020 20,435 $1,599,416 $81.27 $1,660,720

2021 21,540 $1,685,945 $82.27 $1,772,105

2022 22,705 $1,777,154 $83.27 $1,890,682

2023 23,934 $1,873,298 $84.27 $2,016,901

2024 25,229 $1,974,644 $85.27 $2,151,244

2025 26,593 $2,081,472 $86.27 $2,294,220

2026 28,032 $2,194,080 $87.27 $2,446,370

2027 29,549 $2,312,779 $88.27 $2,608,267

One might argue that waste disposal growth might diminish over time, particularly in response

to increased fees. Actual disposal history, however, shows little to no price sensitivity of

disposal quantities in reaction to price increases. For example, franchise haulers’ tipping rates

increased from $74.34/ton to $76.73/ton (3.2%) from 2014‐2016, but tons of MSW increased

from 14,068 to 16,551 (17%).

20180612 Visioning p. 29

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 26 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Table 6‐4: Evaluation of Option 6: Raise Franchise Hauler Tipping Fees

Objective Evaluation

Achieve long term financial stability of Tillamook Solid Waste

Achieves goal

Make self‐hauling at transfer stations financially self‐sufficient.

No impact

Encourage responsible waste disposal practices by all in the community (recycle, dispose locally or at curb, etc.) in the best interest of public health

Negligible impact on behavior

Address recycling crisis Does not directly address goal

Ensure equitable delivery of solid waste services Could reduce economic equity by if costs passed through to raises in curbside fees Maintains equity if paired with self‐hauler tipping fee increase

Conclusions

Increasing franchise hauler tipping fees has the potential to raise approximately $18,000

to $30,000 annually for each $1‐per‐ton increase.

Assuming 100% of this increase is passed through to customers, each $1 per ton

increase would lead to increases in curbside collection fees of approximately 1.1%.

Fee increases of this magnitude have not resulted in noticeable changes in customer

behavior in terms of quantity of waste disposed.

20180612 Visioning p. 30

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 27 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Option7:Localizedimprovementdistrictscenteredaroundsatellitetransferstationswithfallbackoptionofmandatoryservice

Description: This proposal would establish two local improvement districts, centered around

each satellite transfer station (Manzanita in the north, Pacific City in the south). Each district

would provide all solid waste services in their own area, including curbside service and

operation of the satellite transfer station. Local levies would pay for garbage service. The

proposal would be put to a separate vote in each district, with the fallback being mandatory

curbside service in that district if the vote to create the district fails.

Background: Satellite transfer stations lose money each year, with operational costs exceeding

revenues from self‐hauler fees, although that loss figure has declined over the past three years

from around $36,000 in FY2014‐15 to about $14,000 in FY2016‐17. This proposal aims primarily

to make those satellite stations financially self‐sufficient through local levies for the areas

principally served.

ProsandCons

Pros Cons

High revenue potential

Overcomes Measure 5/97 limitation on Solid Waste Fee

Raises funds for local service from local sources

Directly addresses goal of satellite transfer station self‐sufficiency

Contains a fallback option

Possible adverse public reaction

Possible perception of unfairness – north & south county residents “paying more”

Unknown legal authority to implement the change

High administrative/setup costs

Possible loss of revenue to TCSW (fewer haulers paying franchise fees, loss of SW fee for properties in new districts)

Analysis

Local Improvement Districts (LIDs) present an opportunity to find revenue for solid waste

services in Tillamook County through the property tax mechanism. LIDs that raise funds for

specific service or infrastructure improvements in a defined geographic area have been deemed

by the courts as fees rather than taxes and thus avoid Measure 5/97 tax limits and compression

20180612 Visioning p. 31

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 28 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

rules that otherwise prevent use of this option.5 LID financing is generally through sale of

bonds, repaid by LID assessments on benefiting properties on the property tax bill.

For the purpose of this analysis, we will assume that the three service districts would be

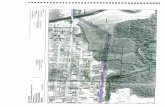

created as follows (see map, Figure 7‐1):

LIDDistrict1(North):

Consists of areas surrounding and supported by Manzanita Transfer Station, served by R

Sanitary and Recology. Includes Garibaldi, Manzanita, Neahkahnie, Nehalem, Rockaway

Beach, and Wheeler.

LIDDistrict2:(South):

Consists of areas surrounding and supported by Pacific City Transfer Station, served by

Nestucca Valley Sanitary. Includes Pacific City, Beaver, Cloverdale, Hebo, and Neskowin.

NoLID:TillamookCityandenvirons

Consists of areas served by City Sanitary and Oceanside Sanitary. Includes Tillamook City,

Bay City, Netarts, Oceanside and Cape Meares.

It is assumed that the revenue available to each LID is the sum of per‐property fees currently

collected in each district, i.e. monthly solid waste fees plus garbage collection service fees.

For this analysis we required statistics that were not readily available and required some

estimation. These included the number of developed properties and the solid waste fees

collected in each district. These were derived as follows.

We estimated the number of properties in each district to be proportional to the population of

the cities listed above for each district, using the most recent population statistics consistently

available from the U.S. Census.6 That ratio was multiplied by the number of developed

properties, calculated to be 19,583 (based on estimates of Solid Waste Fee revenue in the

budget).

The solid waste fees collected in each district was derived by multiplying the number of

properties times $12 per month.

5 Martin v. City of Tigard, according to "Local Improvement Districts: Do’s, Don’ts and What If’s, What You Need to Know about LIDs,” by Shannon Johnson, City of Keizer; Mike Kohlhoff, City of Wilsonville; Andrew Aebi, City of Portland. 6 This forced us to use data from 2000, as more recent census data were not available for smaller cities.

20180612 Visioning p. 32

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 29 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Figure 7‐1. LID Service Districts

20180612 Visioning p. 33

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 30 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Table 7‐2 provides the total revenue produced on a property‐by‐property basis (i.e., total

collection service fees and solid waste fees) in each proposed LID.

We assume that there will be start‐up costs incurred in the establishment of two new local

service districts, and ongoing administrative costs of replacing existing fees with a new levy. As

with the Solid Waste District scenario, we assume one‐time public education costs of $5 per

developed property, or about $98,000.

Table 7-2 Total Solid Waste Revenue by LID District

Tillamook District 1 (North)

District 2 (South)

Grand Total

Population 47.0% 39.7% 13.3% 100%

Developed Properties 9,198 7,777 2,608 19,583

Solid Waste Fees $110,374 $93,328 $31,294 $234,996

Collection Revenue $1,084,631 $552,615 $1,035,046 $2,672,292

Total Revenue $1,195,005 $645,943 $1,066,340 $2,907,288

For ongoing costs, we assume that each LID will require a half‐time staff person (0.5 FTE), with

an offsetting reduction of 0.5 FTE in County staff. Based on the County costs per FTE (including

associated materials and services), this results in an ongoing cost of $61,556 per service district,

and a reduction of the same amount to the County budget.

We further assume that the net operating gains/losses incurred at each transfer station would

accrue to the district in which they reside, and that the corresponding LID district would be

assessed the amount needed to cover those losses.

Table 7‐3 summarizes the impact of these costs on revenues and average levy costs per

property in each LID. Note that the “non‐LID” section centered around Tillamook City would see

a reduction in fees, while the two LIDs would see increases in order to cover the deficits and

additional staffing costs.

20180612 Visioning p. 34

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 31 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Table 7-3 Levy Requirements by LID District

Tillamook District 1 (North)

District 2 (South)

County Total

Total Revenue $1,195,005 $645,943 $1,066,340 $2,907,288

Subsidy ($60,320) $49,847 $24,929 $14,456

LID Setup/Ops costs ($56,953) $65,447.78 $65,447.78 $73,942.74

Net budget impact ($117,273) $115,295 $90,377 $88,399

Total Revenue Required $1,077,732 $761,238 $1,156,717 $2,995,686

Average annual levy per developed property

($12.75) $14.82 $34.66 $4.51

Change as % of SW Fees ‐9.8% +17.8% +8.5% +3.0%

We assume for this analysis that the revenue target for the levy in each district will be the

amount indicated in the “Total Revenue Required” line of Table 7‐3. The next line below shows

the annual change (increase or decrease) to the tax on the “average property” in each LID. The

final line of the table shows the impact as a percentage of current solid waste fees paid in each

LID. Table 7‐4 illustrates what the impact of these cost shifts would have in each LID if the costs

and revenue shifts were applied to average garbage collection rates.

Table 7‐4 Average Change to Monthly Garbage Service Fees

by LID and type of property use

Tillamook LID 1 LID 2

Household ($2.34) $3.60 $2.35

1 yard container ($10.78) $20.88 $8.67

2 yard container ($18.87) $40.22 $14.70

3 yard container ($28.58) $56.46 $1.82

The LID option assumes, however, that a levy would replace curbside collection fees and the

existing solid waste fee.

Table 7‐5 below shows the impact of these cost and revenue shifts on average property tax

rates in each district.

20180612 Visioning p. 35

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 32 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Table 7‐5 Impact of Cost and Revenue shifts of LIDs on Average Property Tax Rates

County‐wide Tillamook LID 1 LID 2

2017‐18 Property Tax Revenue

$6,600,000 $3,099,915 $2,621,178 $878,907

SW Revenue $2,907,292 $1,195,005 $645,943 $1,066,340

Target New Revenue $85,812 ($117,273) $115,295 $87,790

Prop Tax change required to generate target revenue

1.30% ‐3.78% 4.40% 9.99%

Table 7‐6 applies the property tax impacts in Table 7‐5 to example properties in each LID.

Table 7‐6. Estimated Annual Levies by LID Districtfor “Typical” Properties in Tillamook County

Property description LID 1 (North) LID 2 (South) Tillamook area

1500 sq.ft. 3 BR home $92 $210 ($79) Tillamook 2,200 sq ft retail $167 $380 ($144) 1,700 ft Commercial/Ind. $62 $140 ($53) 2,800 sq ft restaurant $131 $298 ($113) Big box retail (25,000 sf) $363 $824 ($312) 30‐40 unit apartment building $827 $1,878 ($711) Med sized hotel $1,194 $2,712 ($1,027)

Table 7‐7: Evaluation of Option 7: Create North/South LID Districts

Objective Evaluation

Achieve long term financial stability of Tillamook Solid Waste

Achieves goal

Make self‐hauling at transfer stations financially self‐sufficient.

Achieves goal

Encourage responsible waste disposal practices by all in the community (recycle, dispose locally or at curb, etc.) in the best interest of public health

Likely to increase curbside disposal; may disincentivize curbside separation

Address recycling crisis Does not directly address goal

Ensure equitable delivery of solid waste services Significantly increases costs to residents of LIDs and reduces costs to central county residents

20180612 Visioning p. 36

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 33 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Conclusions

LIDs provide a property‐based funding mechanism that avoids Measure 5/97 limitations

and compression rules and are a very powerful and efficient method of raising revenue

for public services.

Self‐sufficient LIDs could be created to serve areas surrounding the satellite transfer

station areas based on existing service boundaries by franchise haulers.

Start‐up and ongoing operating costs would total approximately $72,000 per year for

each LID over the ten‐year period, with offsetting reductions of about $57,000 to the

County.

If LIDs are designed to capture and eliminate subsidies currently provided to the satellite

stations as well as cover additional operating and startup costs in those districts, the

result would be a significant shift of costs to properties in the LIDs and a reduction of

costs to the remaining non‐LID area around Tillamook City.

Cost impacts would be greatest in the southern LID. Levy impacts could result in

properties of equal value paying hundreds to thousands more in LID 2 than in the

Tillamook area.

20180612 Visioning p. 37

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 34 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Option8:RaiseSolidWasteFee,indexedtoinflation

Description: Raise the Solid Waste Fee and index the fee to inflation

Background: The County currently charges a $1 monthly fee per developed property for solid

waste services, collected on the property tax bill. The revenue accrues directly to the County.

Measure 5/97 restrictions limit the County’s ability to adjust this fee, which has not risen since

1985, with a 57% reduction in purchasing power.

ProsandCons

Pros Cons

High revenue potential

Makes the fee sustainable

Even significant percentage increases would not have great impact on tax bills

Likely adverse public reaction

Tax compression

Analysis

LegalAuthority

In February 1985, Tillamook County enacted a solid waste fee of one dollar per developed

property per month, which was approved by county voters in March 1985. The fee has

remained at that level since that time.

Ballot measures 5, 47, and 50, approved by Oregon voters in the 1990s, amended the Oregon

constitution and collectively limited the County’s authority to raise the fee. Measure 5 limited

total nonschool property taxes to one percent ($10 per $1,000 real market value), which

significantly limited local revenue options.7 Most general government tax and fee line‐items on

the property tax bills were consolidated under the 1% cap. Further, under Measure 5, any

additions to property taxes creates “compression:” If either the school or general government

taxes exceed the 1% limit, then each corresponding taxing district’s tax rate is reduced

proportionately until the tax limit is reached.8 Moreover, taxes are compressed in a specific

order. First, local option taxes (which would include the Solid Waste Fee) are reduced, possibly

to zero. If there are no local option taxes or they have been reduced to zero, the tax rates from

the permanent tax rates for each taxing district are reduced proportionately.

7 The Oregon Encyclopedia. https://oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/measure_5_property_taxes/#.WkaCilFG2Uk. Accessed December 29, 2017. 8 Oregon Department of Revenue, “A Brief History of Oregon Property Taxation,” http://www.oregon.gov/DOR/programs/gov‐research/Documents/303‐405‐1.pdf, accessed October 31, 2017.

20180612 Visioning p. 38

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 35 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Measures 47 (passed in 1996) and 50 (1997) amended some of Measure 5’s provisions. Most

significantly, Measure 47 reduced property tax rates and created the “double majority” rule,

under which any tax increase in a non‐presidential election year required that (1) a majority of

eligible voters must cast ballots and (2) a majority of those voting must approve the increase. 9

Further, Measure 47 limited the total dollar amount of any tax increase to 6 percent larger than

the highest amount levied in the three prior years. Tax base levies could be increased in

proportionate amounts for annexed territory. A taxing district was permitted to have only one

tax base levy. Proceeds from the tax base levy could be expended for any purpose allowed by

law for the district except general obligation bonds. Tax base levies were subject to the

Measure 5 tax rate limits. 10

Measure 50, passed by the legislature and approved by voters, fixed some technical issues with

Measure 47, most notably by “switching to permanent rates, reducing assessed values, and

limiting annual growth of assessed value” to 3% annually. Measure 50 replaced most tax levies

with permanent tax rates. Therefore, the exercise of setting tax rates remains only for local

option levies, bond levies, and urban renewal special levies (such as LIDs). 11

In summary, the County has the legal authority to raise the fee, but it would encounter

significant compression issues and, if pursued, could face serious obstacles at the ballot box.

Landfills

The justifications for raising the fee, in spite of those obstacles, are fairly straightforward. The

revenue raised by the Solid Waste Fee has been dedicated historically to defraying the costs

associated with the county’s decommissioned landfills. Those costs now amount to about

$255,000 per year. The fee currently raises about $235,000 annually, leaving a deficit of

$20,000. Table 9‐1 shows that a $0.09 fee increase would be required to close the deficit. If

indexed to inflation, the fee would rise to $1.32 per month in 2027.

Table 8‐1 Solid Waste Fee Increases Required to Close Deficit

in Landfill/RHC Costs

2017 Revenue $235,000

Cost of closed landfills, RHC $255,200

Deficit vs. SW Fee ($20,200)

Monthly Fee required, net $1.09

2027 monthly fee, indexed $1.32

9 ODOR, “A Brief History of Oregon Property Taxation.” 10 ODOR, “A Brief History of Oregon Property Taxation.” 11 ODOR, “A Brief History of Oregon Property Taxation.”

20180612 Visioning p. 39

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 36 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

LostPurchasingPower

The Solid Waste Fee has lost 57% of its purchasing power since enacted in 1985. The amount raised

currently represents about $546,000 in 1985‐equivalent dollars.

Table 8‐1 above shows that the fee would need to rise to $2.33 per month in order to regain

1985 purchasing power (i.e., produce $546,512 in revenue). If indexed to inflation, the fee would

rise to $2.83 per month in 2027 and yield $664,744 in annual revenue, as shown in Table 8‐2.

Table 8‐2 Solid Waste Fee Increases Required to Close Deficit in

Landfill/RHC Costs

Current SW Fee revenue $235,000

1985 purchasing power of current revenue $546,512

Purchasing power deficit vs. 1985 ($311,512)

Revenue per $1 annual increase ($0.12/mo) $19,583

1985 break‐even annual fee increase $15.91

1985 break‐even monthly fee increase $1.33

New fee, net $2.33

2027 monthly fee, indexed to inflation $2.83

2027 Annual Revenue (est.) $664,744

Table 8‐3: Evaluation of Option 8: Raise Solid Waste Fee

Objective Evaluation

Achieve long term financial stability of Tillamook Solid Waste

Achieves goal

Make self‐hauling at transfer stations financially self‐sufficient.

Does not address goal

Encourage responsible waste disposal practices by all in the community (recycle, dispose locally or at curb, etc.) in the best interest of public health

Does not address goal

Address recycling crisis Does not address goal

Ensure equitable delivery of solid waste services Slightly reduces economic equity

Conclusions

Raising the Solid Waste Fee and indexing the fee to inflation could generate substantial and

sustainable revenue increases for solid waste services in Tillamook County. However, legal and

political uncertainties (potential voter opposition) make enactment of such an increase

problematic.

20180612 Visioning p. 40

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 37 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Option9:Recyclingco‐op

Description: This proposal would create a recycling co‐op in Tillamook County, as part of or

independent of mandatory service.

Background: Recycling co‐ops are membership‐owned and operated organizations that make

recyclable materials and/or recycled goods available at cost to its members, for reuse in the

manufacturing of newer goods or versions of goods to be sold to customers at cheaper prices

than would be possible with freshly obtained raw materials. Typical products offered are paper

products, glass products, fuels, paint, and metals, among others. Co‐ops provide enhanced

market power for selling recyclables in the secondary market by pooling collected materials,

opening up markets not available to smaller players and leveraging their increased size for

better volume pricing.

ProsandCons

Pros Cons

Addresses recycling crisis

Removes much of recycling tonnage and sorting issue from transfer stations

Recovers revenue from sale of raw or processed materials

Addresses issue of recycling product backlog/weak market

Co‐ops often struggle to break even, may require subsidy at least at first

Unknown legal authority to implement

Some administrative/setup costs

Possible loss of revenue to TCSW (reduction of trips/minimum fees by self‐haulers)

Note that this proposal, if adopted, would expand the role of the County to a new area, which

was previously overseen independently by the operators with no County impact on SW funding.

Analysis

Recycling co‐ops in the U.S. tend to take one of three forms:

1. Advocacy and educational groups that share information on best practices with

members and advocate in the community and legislatures for recycling‐friendly policies

and funding. Examples include Kaufman County Environmental Co‐op in Terrell, TX;

Northeast Recycling Council (https://nerc.org/), an 11‐state co‐op in Brattleboro, VT; In

the U.K., the South Shore Recycling Cooperative (http://ssrcoop.info/) provides a similar

role.

2. Technical assistance co‐ops, who assist recycling and disposal companies in various

ways such as finding markets for their recyclables, help negotiate contracts, and assist in

setting up waste disposal programs and operations. Examples include INC

20180612 Visioning p. 41

Prepared by Innovative Growth Solutions Page 38 of 43 Revised May 15, 2018

Environmental Recycling (http://www.incenvironmentalrecycling.com/) in O’Fallon, MO;

Eureka Recycling Zero Waste Buying Co‐op (http://www.eurekarecycling.org/zero‐

waste‐buying‐co‐op) in Minneapolis, MN (which also holds semi‐annual public sales of

goods made from recycled materials); and Cooperative Teamwork & Recycling

Assistance (CTRA) of Austin, TX (http://www.recyclingassistance.org/ctra.html).

3. Operational co‐ops, which perform or coordinate some or all of the operational

functions of a recycling or waste disposal facility, such as Oregon Beverage Recycling

Cooperative (http://[email protected]), which picks up and recycles beverage bottles and