THRACIANS – ILLYRIANS – CELTS. CULTURAL ......see Dzino, Domi} Kuni} 2012; for prior ethnic...

Transcript of THRACIANS – ILLYRIANS – CELTS. CULTURAL ......see Dzino, Domi} Kuni} 2012; for prior ethnic...

33

During the 4th century and at the beginning ofthe 3rd century BC, the Carpathian Basin wit-nessed an eastward and southward extension

of the area inhabited by Celtic communities. Theiradvance was slow, in successive phases that lasted sev-eral generations, and can be noted in the distributionand chronology of the cemeteries from the mentionedarea. One result of this colonisation is the appearanceof some new communities characterised by the cultur-al amalgamation of the newcomers with the indige-nous populations, which developed new ways of con-structing and expressing their collective identities1. Atthe same time, the “colonists”2 established differentsocial, political or economic relationships with differ-ent indigenous populations of the Balkans. This articlediscusses some practices that can be related to the cul-tural interactions between the aforementioned commu-nities and the ways in which these connections can be

identified through the analysis of material culture fromthe eastern and southern Carpathian Basin, and fromthe northern and north-western Balkans. In this case,

THRACIANS – ILLYRIANS – CELTS.

CULTURAL CONNECTIONS IN THE NORTHERN BALKANS

IN THE 4th–3rd CENTURIES BC

AUREL RUSTOIU, Institute of Archaeology and History of Art, Cluj–Napoca, Romania

UDC: 903´1"(497-17)"-03/-02"903.2"(497-17)"-03/-02"

https://doi.org/10.2298/STA1767033ROriginal research article

e-mail: [email protected]

Abstract – The result of the colonisation of the eastern and southern part of the Carpathian Basin by Celtic communities was theappearance of some new communities characterised by the cultural amalgamation of the newcomers with the indigenous populations,which led to the construction of new collective identities. At the same time, the “colonists” established different social, political or economic relationships with different indigenous populations from the Balkans. This article discusses the practices related to the cultural interactions between the aforementioned communities and the ways in which these connections can be identified throughthe analysis of material culture from the eastern and southern Carpathian Basin, and the northern and north-western Balkans.

Key words – Thracians, Illyrians, Celts, Carpathian Basin, northern Balkans, Alexander the Great, La Tène culture, funerary customs.

This work was supported by a grant of Ministry of Research and Innovation from Romania, CNCS – UEFISCDI, project number PN-III-P4-ID-PCE-2016-0353, within PNCDI III.

1 Rustoiu 2008, 65–98; 2014.2 Some recent studies have shown that a single “theory of

colonialism” or “model of colonisation” cannot be drawn (see forexample Dietler 2005, 54–5; Gosden 2004). At the same time the“colonisation” cannot be regarded as a simple movement from oneterritory to another, as it presumes a diverse range of interactionsbetween the “colonists”, having their own personal and group iden-tities and agendas, seeking to impose their own norms, habits andideology, and the “colonised” who also have specific identities andare either exerting various forms of resistance, or are expressing adegree of openness towards integration into the newly built com-munal structures (Given 2004; for the eastern Carpathian Basin seeRustoiu 2014; Rustoiu, Berecki 2016). These diverse interactionscontribute to the transformation of individual and group identities,leading to the creation of some new ones through cultural “hybridi-sation” and even through the re-invention of some traditions.

Manuscript received 26th October 2016, accepted 10th May 2017

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

the terms “Thracians”, “Illyrians” and “Celts” have noethnic meanings (native or modern), being instead usedto identify different groups of populations from thenorth-eastern and north-western Balkans and the Car-pathian Basin, which were named in this way by vari-ous ancient authors while writing about the respectiveregions3.

A short socio-political overview

of the regions in question

First, it is important to identify the “actors” involvedin this network of cultural exchanges in the 4th–3rd

centuries BC. The communities from the northern andnorth-western Balkans seem to have largely evolvedalong the traditional lines of the Early Iron Age. Theirsocial hierarchy and the appearance of aristocratic eliteshaving a coherent identity and ideology are mostly visi-ble in funerary contexts. Thus, aristocratic burials con-tain rich assemblages which were meant to reinforcethe social status of the elites within the communities.

In the central and north-western Balkans, tumulusburials containing rich inventories with several goodsof Mediterranean origin had already appeared in the7th–5th centuries BC, illustrating the integration of theselocal elites into a series of wider social and economicnetworks.4 Similar funerary contexts appeared slightlylater in the regions occupied by Thracian populationsfrom the northern and north-eastern Balkans. Thedeceased (men and women) were interred in structuresincluding funerary chambers which were covered bylarge mounds. In some cases (Vraca, Sboryanovo,Agighiol, etc.) these constructions also had antecham-bers (some containing sacrificed horses) or annexes,and were built of stone blocks carved in the Greektechnique by Greek masons5. The large majority ofthem were inspired by Macedonian funerary construc-tions, and the royal cemetery at Vergina is commonlyconsidered to be a suitable analogy.6 Sometimes, Me-diterranean ornaments and symbols were taken over,adapted and reinterpreted in the local manner. This isthe case with the stone caryatids decorating one of thetumuli from Sboryanovo, which imitate Mediterraneanprototypes in a “barbarised” style, or with the paintingsshowing the royal investiture on the walls of somefunerary chambers from the same site.7 However,there is a significant variation in what concerns thequality of the masonry of the funerary monumentsfrom the region in question. Thus, mostly those built tothe north of the Danube (for example at Peretu orZimnicea8) were built much simpler. On the one hand,

this variation reflects the different degree of access tothe network of social and economic connections estab-lished between the local dynasts and the Greek envi-ronment, which provided Mediterranean goods andartisans. On the other hand, it points to the existence ofan aristocratic hierarchy which was expressed in thefunerary practice, among other things.9

Regarding the funerary inventories, from a functi-onal point of view they include: a) weapons and mili-tary equipment; b) harness fittings; c) jewellery andcostume accessories; d) metal (silver or bronze) andceramic ware. The same categories of goods have alsobeen found in hoards (many accidentally discovered,so some could in fact be funerary inventories belongingto some destroyed burials) or fortified settlements.10

The figurative art on certain metal artefacts (ves-sels, helmets, greaves, plaques etc.) or the paintings onthe walls of some funerary chambers indicate the exis-tence of a coherent ideological vocabulary which wasspecific to the aristocracy of the northern Balkans.This visual language combines and reinterprets stylis-tic and iconographic elements having various origins(Scythian, Achaemenid or Greek) in a specific and ori-ginal manner.11 The typical iconographic themes consistof male riders usually involved in hunting scenes (ofboars, bears or lions), male and female characters inceremonial chariots, sacrifice scenes, winged femaledivinities in the mistress of animals pose, hierogamyscenes, fighting beasts, processions of real and fantas-tic beasts, mythical heroes (for example Herakles) etc.

Accordingly, the entire funerary phenomenon ofthe 5th–3rd centuries BC from the northern Balkansillustrates a major differentiation between the ordinarymembers of the communities and the aristocratic eliteswhich dominated the social-political, economic andreligious life. These elites also had their own social

STARINAR LXVII/201734

3 For the ancient authors’ perception of various populationsfrom these regions and the construction of ancient “ethnonyms”,see Dzino, Domi} Kuni} 2012; for prior ethnic identifications, seefor example Papazoglu 1978; Szabó 1992.

4 See Babi} 2002.5 Tsetskhladze 1998.6 Mãndescu 2010, 377–418.7 ^i~ikova 1992; Fol et al. 1986.8 Moscalu 1989; Alexandrescu 1980.9 Babeº 1997, 232–233; Rustoiu, Berecki 2012, 169–170, Pl. 8.10 Kull 1997; Sîrbu, Florea 2000; Mãndescu 2010, 377–418,

with previous bibliography.11 Alexandrescu 1983; 1984.

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201735

Fig. 1. 1) Grave no. 17 from Remetea Mare (after Rustoiu, Ursuþiu 2013); 2) Funerary pottery from the Zimnicea cemetery (after Alexandrescu 1980). Different scales

Sl. 1. 1) Grob br. 17, Remetea Mare (prema: Rustoiu, Ursuþiu 2013); 2) Grobna grn~arija, grobqe u Zimni~ei (prema: Alexandrescu 1980). Razli~ite razmere

1

2

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201736

Fig. 2. 1) Cremation grave no. 10 containing a rectangular timber structure from Fântânele–Dâmbu Popii inTransylvania (after Rustoiu 2008). Similar graves in Central-Eastern Europe: 2) Grave no. 734 from Ludas inHungary (after Tankó, Tankó 2012); 3) Grave no. 448 from Malé Kosihy in Slovakia (after Bujna 1995)

Sl. 2. 1) Grob sa kremacijom br. 10 sa pravougaonom drvenom konstrukcijom, Fantanele-Dambu Popiu Transilvaniji (prema: Rustoiu 2008). Sli~ni grobovi u centralno-isto~noj Evropi: 2) Grob br. 734, Luda{ u Ma|arskoj (prema: Tankó, Tankó 2012); 3) Grob br. 448, Male Kosihi u Slova~koj (prema: Bujna 1995)

1 3 6

5

4

1

32

2

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201737

hierarchy, being oriented towards the cultural models ofthe Odrysian or Macedonian dynasts. In spite of theseinfluences, the aristocracy of the northern Balkansconstructed its own ideology which incorporated cer-tain practices of heroisation, illustrated by the iconog-raphy and the funerary and commemorative rituals.12

Largely at the same time, many communities fromthe Carpathian Basin experienced a process of socialreconfiguration and cultural hybridisation resultingfrom the cohabitation of the Celtic “colonists” withsome of the local populations13. A series of funerarycontexts could offer relevant examples regarding thenature of the interactions between these two main par-ties. However, the range of these interactions variedsignificantly from one community to another, so a gen-eral model that would be valid for the entire area of theCarpathian Basin cannot be defined14.

Thus, the inclusion of local pottery in certain fune-rary rituals of the newcomers could suggest that somegraves belonged to the locals integrated into the newcommunities established by the Celtic “colonists”. Onegood example is the cremation grave no. 17, in a liddedurn from the Remetea Mare cemetery in the RomanianBanat15 (Fig. 1/1). The funerary ritual, as well as thehandmade pottery, has analogies in cemeteries fromthe Lower Danube region, for example at Zimnicea insouthern Romania16 (Fig. 1/2). For this reason thegrave might be ascribed to an indigenous individual, inspite of the fact that the costume accessories consist ofLT items.

Another case, this time coming from theFântânele–Dâmbu Popii cemetery in Transylvania,offers a very different example. The cremation graveno. 10 contains a rectangular timber structure with twocompartments (Fig. 2/1). The ceramic inventory con-sists exclusively of local handmade vessels17. How-ever, certain elements of the funerary rite and ritual,including the timber structures found in some funerarypits, are also encountered in Late Iron Age cemeteriesfrom the middle Danube region (see, for example, thecemeteries from Malé Kosihy in south-western Slova-kia18 (Fig. 2/3) and Ludas in north-eastern Hungary)19

(Fig. 2/2). Thus, it can be said that the aforementionedgrave from Fântânele more likely belonged to a colo-nist who was buried according to the funerary customsof his homeland.

In spite of this cultural hybridisation, the elites ofthese new communities still preserved a specific iden-tity brought over from the newcomers’ homeland,which continued to be expressed through a particular

visual code. The use of this code also implied thepreservation of certain traditional funerary practicesand visual symbols (for example weaponry or costumeaccessories) associated with the graves of warriors andalso of women. For instance, the metal inventories oftwo graves from the Remetea Mare cemetery in theRomanian Banat – no. 9, containing weapons and no.8, without weapons – (Fig. 3), point to the CentralEuropean origin of the deceased20.

It can, therefore, be said that many cultural featuresof the regions in question were substantially modifiedafter the arrival of the Celtic groups. The new communi-ties that resulted from the amalgamation of the colonistswith the local populations initiated new social contactswith the populations from the northern Balkans. Themechanisms of communication between these com-munities were complex and implied negotiations andagreements that must have taken various forms, beinglargely controlled by the respective elites21.

Forms of distance interactions

Amongst the mechanisms of communication aredirect diplomatic contacts established between theleaders of different communities. These contacts regu-lated the relationships between these communities andalso different aspects related to the pan-regional bal-ance of power during large-scale military campaigns.The movement of armed groups across wide areasimplied the crossing of some territories controlled byforeign communities, and frequently required accessto supply sources or markets that could provide goodsneeded for the campaign. When these resources werenot obtained through the force of arms, the access hadto be regulated on the basis of some negotiated agree-ments22. In this context, it is relevant that during themajor military campaigns of 280–278 BC against

12 See for example Sîrbu 2006, 24–25, 121–126.13 See for instance D`ino 2007; Potrebica, Dizdar 2012, 171;

Rustoiu 2014.14 Rustoiu 2008, 67–80; 2014.15 Rustoiu, Ursuþiu 2013, 326, Fig. 12/1.16 Alexandrescu 1980.17 Rustoiu 2008, 77–78, Fig. 35; 2013, 6–7.18 Bujna 1995.19 Tankó, Tankó 2012.20 Medeleþ ms.; Rustoiu 2008, 111, Fig. 56; 2012a, Pl. 8–9;

Rustoiu, Egri 2011, 32–33, Fig. 10.21 See further comments in Rustoiu 2012a.22 Rustoiu 2006, 58; 2012a, 360–361.

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201738

Fig. 3. Graves no. 9 with weapons (1) and no. 8 without weapons (2) from Remetea Mare (after Medeleþ mss)

Sl. 3. Grob br. 9 sa oru`jem (1) i br. 8 bez oru`ja (2), Remetea Mare (prema: Medeleþ mss)

1

2

1

2

3

4

5 8

6

7

11

12

9

10

19

14

18

13

17

15

16

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201739

Macedonia and Greece the Celtic expeditionary forcesadvanced along the Morava and Vardar rivers. How-ever, some settlements and commercial centres alongthe mentioned route, like the one at Kale–Kr{evica didnot experience any violent destruction.

This settlement, located in the upper basin of theJu`na Morava River, was founded at the end of the 5th

century and/or the beginning of the 4th century BC. Itsend has been dated to the middle or the first half of the3rd century BC23, or even to the first decades of the 3rd

century BC24. P. Popovi} has noted that the latest datedcoin from this site was issued by Demetrios Poliorketes,thus suggesting an end date of the settlement duringthe Celtic invasion in Greece, but there are no otherarguments in favour of this hypothesis since manyother artefacts can be dated later25. Furthermore, noneof the coins from Kale Kr{evica come from clear stra-tigraphic contexts. Recently, M. Gu{tin and P. Kuzmanhave dated the settlement to the second half of the 4th

century and the beginning of the 3rd century BC, con-necting its end with the Celtic invasion. Their dating isexclusively based on numismatic and literary arguments(the few recovered coins cover the period between thereigns of Philip II and Demetrios Poliorketes; the set-tlement is a Macedonian emporium, so it was predicta-bly a target for the invading Celts etc.), without takinginto consideration the chronology of the entire archae-ological inventory, which includes numerous Greekceramic vessels, among other things26.

The settlement at Kale–Kr{evica played an impor-tant role in the circulation of some Mediterranean pro-ducts from Macedonia to the north, to the Celtic, indi-genous environment of the southern Carpathian Basinand the middle Danube at the end of the 4th century andat the beginning or in the first half of the 3rd centuryBC. Thus, one cannot exclude the possibility that somesocial contacts between these communities could havebeen initiated earlier, in spite of the fact that LT findsseem to be absent from this horizon of the settlement.

Regarding a series of settlements belonging to thesame period and located on the Vardar, whose end wasdated to the first decades of the 3rd centuries BC, it hasbeen presumed that their destruction was caused by theCeltic invasion in Macedonia and Greece27. Never-theless, other explanations could also be possible con-cerning both the final date of the aforementioned set-tlements and the cause of their abandonment. Thesupposed destruction of all of these important eco-nomic centres along the Morava–Vardar corridor bythe contingents led by Brennus and Acichorius would

have caused numerous problems regarding supplyingthe expeditionary forces. Concerning the supposed de-struction of some “Hellenised” indigenous settlements28

during the Celtic expeditions in the Balkans andGreece, as has been presumed in the case of Pistiros29

or Seuthopolis30, the analysis of archaeological inven-tories indicates a later date of their abandonment. Thiscan be ascribed to the middle of the 3rd century BC oreven later31. Their abandonment around the middle orin the second half of the 3rd century BC, as in the case ofmany fortified settlements from the northern Balkansor the north-western Pontic region32, could be morelikely related to some important structural changes thataffected the social organisation of these communities.The disappearance of these economic and social cen-tres coincides with the cessation of some contempora-neous practices associated with them, for example thearistocratic tumulus burials with funerary chamberswhich contained spectacular inventories33.

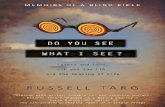

Accordingly, these observations more likely sug-gest that some agreements might have existed betweenthe leaders of the expeditionary forces and those of thecommunities encountered alongside this route. Thesenegotiations were always finalised with gift exchan-ges. Jewellery, luxurious costumes, metal vessels orhorses with rich harnesses, sometimes accompaniedby their stablemen, were commonly included, accord-ing to various ancient authors, in these exchanges (seefor instance Xenophon VII.3.26–27 or Livy XLIII.5).The famous gold torque from Gorni Tsibar, decoratedin the Vegetal Style and dated to around the middle orthe second half of the 4th century BC (Fig. 4/1), wasfrequently interpreted as part of a gift exchange34.

23 Popovi} 2005, 145–160; 2006, 528.24 Popovi} 2007a; 2007b; Popovi}, Vrani} 2013, 309.25 Popovi} 2007a, 415–416.26 Gu{tin, Kuzman 2016, 316, 326–329.27 Mitrevski 2011 with the bibliography; see also Gu{tin, Kuz-

man 2016.28 For the supposed “Hellenisation” of the indigenous settle-

ments see Vrani} 2014.29 Bouzek 2005.30 ^i~ikova 1984, 111; Bouzek 2006, 79 etc.; see the relevant

bibliography in Emilov 2010, 77.31 Regarding Seuthopolis and its final dating, see the com-

ments in Emilov 2010, 75–79.32 For the chronology of the sites from these regions see fur-

ther comments in Mãndescu 2010.33 Rustoiu 2002, 66.34 Theodossiev 2005, 85–86; Emilov 2007, 58 etc.

Vincent Megaw has noted that the origin of this object,found in north-western Bulgaria, must have beenWestern Europe or Italy. The gold torque from graveno. 2 at Filottrano near Ancona (Fig. 4/2), in a regioninhabited by the Senones, is a close analogy35.

Ruth and Vincent Megaw have noted that the Ve-getal Style decoration of the piece from Gorni Tsibar isalso encountered on ceramic vessels from the CarpathianBasin, for example at Alsópél in Hungary. However,an eastern origin of the torque from the north-westernBulgaria is less likely due to the morphology of thepiece, the use of gold and the absence of any other ana-logy from the region36. Nevertheless, the Vegetal Stylesurvived in the decorative repertoire of the potteryfrom the Carpathian Basin until the middle LT period.Amongst the arguments can be listed the beaker froma grave with a helmet, uncovered at Apahida in Tran-sylvania37, as well as the bi-truncated vessel from aCeltic burial discovered at Moftinu Mic in north-west-ern Romania38. The latter has an incised and stampedcrescent-shaped decoration that is morphologicallysimilar to the one on the ends of the torque from GorniTsibar. At the same time, pieces that resemble the arte-fact in question are less commonly encountered in theCarpathian Basin and are made of bronze39. Gold wasvery rarely used in the Carpathian Basin at the beginningof the early LT period, in spite of the rich resourcesfrom Transylvania. All these observations argue againfor a western European origin, and not an eastern one,of the torque from Gorni Tsibar.

The dating of these artefacts corresponds to theexpedition of Alexander the Great to the Danube in335 BC, which probably reached the mouth of the Mo-rava. Vasile Pârvan, analysing ancient literary sources,once localised the expedition of Alexander the Great

against the Triballi and then against the Getae from thenorth of the Danube in northern Bulgaria and the Wal-lachian Plain eastward to the mouth of the Olt River.He located a poorly fortified Getic settlement conqueredby the Macedonian king at Zimnicea, where a fortifiedsettlement dated to the 4th–3rd centuries BC had alreadybeen identified. Along the same line, a similar identifi-cation could have been presumed for any other site datedto the same period and located on the lower course ofthe Argeº River40, a hypothesis that was subsequentlyadopted by numerous researchers41. Florin Medeleþ,also starting from literary sources, but taking into con-sideration the general historical context of the time ofPhilip II and Alexander the Great, certain ancient geo-graphic and topographic particularities, and the prob-lems related to the location and extension of the terri-tories belonging to certain communities (like those ofthe Triballi, Getae, Scordisci etc.), convincingly demon-strated that the army of Alexander the Great reached theDanube near the mouth of the Morava. The island onwhich the Triballi took refuge is very probably theOstrovo Island in Serbia, and the Getic fortified settle-ment was located on the left bank of the Danube in thesouthern Serbian Banat42. Alexandru Vulpe rejected this

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201740

35 Megaw 2004, 96; see also Megaw, Megaw 2001, 119–120;for the torque from Filottrano see Megaw 1970, 96–97, no. 128.

36 Megaw, Megaw 2001, 119–120.37 Zirra 1976, 144, Fig. 11/8.38 Németi 2012, 72–73, Pl. 1–2.39 See Bujna 2005, 15–16, type BR-A3A-B, fig. 5.40 Pârvan 1926, 46.41 Vulpe 1966, 11, 19; 1988, 96; Daicoviciu 1972, 20; Turcu

1979, 22–23 etc.42 Medeleþ 1982; German version in Medeleþ 2002.

Fig. 4. 1) Gold torque from Gorni Tsibar (photo Krassimir Georgiev); 2) Gold torque from grave no. 2 at Filottrano near Ancona (after Megaw 1970)

Sl. 4. 1) Zlatne grivne, Gorwi Cibar (fotografija: Krasimira Georgijeva); 2) Zlatne grivne iz groba br. 2, Filotrano kod Ankone (prema: Megaw 1970)

1 2

hypothesis and proposed another location for the cam-paign, downstream at the Danube’s Iron Gates inOltenia43. Although the arguments of A. Vulpe are lessconvincing, they reflect the abandonment of the “tra-ditional” hypothesis placing the Macedonian militaryactions in northern Bulgaria and the Wallachian Plain.Moreover, Fanula Papazoglu has noted that the loca-tions proposed over time for the region in which Ale-xander was active along the Danube cover the lengthof the river between the mouth of the Morava and theDanube Delta. She has opted for a location betweenthe Isker and Timok44. V. Iliescu has also proposed alocation of the events and of the island on which theTriballi took refuge, close to the Iron Gates45, an ideathat was recently adopted by K. Nawotka. However,the latter author inexplicably locates the crossing ofthe Danube by Alexander’s army between Svishtovand Zimnicea46 (!?). Lastly, one has to note the rele-vant observations of Dyliana Boteva regarding theroute followed by Alexander across the Balkans, alsoopting for a location of the events in the Iron Gatesregion47. The most convincing hypothesis is the oneformulated by Medeleþ as it seems to largely reflect thehistorical and geographic information provided by an-cient literary sources. Nevertheless, the opinions pro-posing a localisation of the expedition of Alexander theGreat downstream at the Iron Gates need further deba-te, perhaps also taking into consideration archaeologicalevidence.

On that occasion, alongside the emissaries of localpopulations seeking to meet the Macedonian king werealso those of the Celts from the Adriatic or the IonianGulf, identified as the Italic Senones48, with whomAlexander concluded an alliance (Arrian I.4.6–8; StraboVII.3.8–C 301). Nevertheless, the presence of the torqueat Gorni Tsibar on the Danube’s bank could also be acoincidence.

A series of connections established by the commu-nities of the southern Carpathian Basin with the ItalicPeninsula in the same period are also illustrated byother discoveries. This is the case of a bronze helmet,probably found together with a rigid necklace alsomade of bronze, in the surroundings of Haþeg in south-western Transylvania49 (Fig. 5/2–3). Similar pieces areknown from a series of cemeteries located in the sur-roundings of Ancona (Fig. 5/1), in a region inhabitedby the Senones50.

The presence of such finds in Late Iron Age buri-als from the southern Carpathian Basin is more likelythe result of the occasional individual mobility (for

example that of a group of “negotiators”, although otherforms of individual mobility could also be taken intoconsideration), than of some systematic distant con-tacts. Perhaps the presence of the gold torque at GorniTsibar can also be interpreted in the same manner.

The material effect of negotiations finalised withgift exchanges can also sometimes be noted in the op-posite direction, from the south to the north. For instan-ce, a “Hellenistic” iron horse bit comes from a destro-yed burial uncovered in the cemetery at Ciumeºti innorth-western Romania (Fig. 6/2) first used in the firsthalf of the 3rd century BC51. Similar horse bits havebeen found in graves usually dated to the 5th–4th centu-ries BC52, but such items also continued to be used later,as the funerary inventory of the Padea–Panaghiurskikolonii type from Viiaºu in Oltenia (Fig. 6/3) seems tosuggest53. From a distribution point of view, one has tonote their concentration in eastern Bulgaria54 (Fig. 6/1).The presence of this type of harness fitting in the Celticcemetery from Ciumeºti in the eastern CarpathianBasin, where other types of horse bits were commonlyused during this period55, may suggest that the warlikeelites of the respective community had connectionswith communities from the Balkans. Perhaps horseswearing the harnesses specific to their original landwere included among the gifts exchanged with thesepeople living south of the Danube, as part of someunknown agreements.

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201741

43 Vulpe, Zahariade 1987, 98, 115, n. 27; Vulpe 2001, 458.44 Papazoglu 1978, 28–35.45 Iliescu 1990 – non vidi.46 Nawotka 2010, 97.47 Boteva 2002, 29–30. For a synthesis of the problem in the

Bulgarian historiography see Yordanov 1992.48 See, for example, Kruta 2000, 240–241. Other researchers

attempted to identify the origin of these “Adriatic” Celts by locat-ing them in northern Italy, Pannonia and/or the Danube Basin, or inthe north-western Balkans: Papazoglu 1978, 273–274; Zaninovi}2001; Gu{tin 2002, 11–13.

49 Rusu 1969, 294; Ferencz 2007, 41–42.50 Schaaff 1974, 188–189, Fig. 31/2, 32 – distribution map;

Schaaff 1988, 317, Fig. 39/3, 40 – distribution map.51 Bader 1984; Rustoiu 2008, 17; 2012b, 163.52 Werner 1988, 34–36, type IV.53 Berciu 1967, 86, 89, Fig. 5/1, 3 and Fig. 7.54 The horse bit from Ciumeºti and the one recently discov-

ered in a tumulus burial with a funerary chamber from Malomirovo/Zlatinitsa (Agre 2011, 122–123, Fig. IV–24a–25) can be added tothe repertoire of discoveries and the distribution map published byWerner (1988, 34–36, Pl. 68/B).

55 See Zirra 1981; Werner 1988.

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201742

1 3

2

Fig. 5. 1) Distribution map of the bronze helmets with mobile trefoil-shaped cheek-pieces (after Schaaff 1974; 1988);2) Bronze torque from Haþeg (after Rusu 1969); 3) Bronze helmet from Haþeg (after Moreau 1958)

Sl. 5. 1) Karta rasprostrawenosti bronzanih {lemova sa pomi~nim {titnicima za obraze u oblikutrolista (prema: Schaaff 1974; 1988); 2) Bronzane grivne, Haceg (prema: Rusu 1969); 3) Bronzani {lem, Haceg (prema: Moreau 1958)

1 3

2

Fig. 6. 1) Distribution map of the Werner type IV iron horse bit (adapted and completed after Werner 1988); 2) Iron horse bit from Ciumeºti (after Bader 1984); 3) Iron horse bit from Viiaºu (after Berciu 1967).

Sl. 6. 1) Karta rasprostrawenosti gvozdenog |ema tipa Verner IV (prilago|eno i kompletirano prema:Werner 1988); 2) Gvozdeni |em, ^ume{ti (prema: Bader 1984); 3) Gvozdeni |em, Vija{u (prema: Berciu 1967)

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

It should also be noted that from the same cemeterycomes the famous funerary inventory containing a hel-met and a pair of bronze greaves of Greek origin (Fig.7/1–2), which must have belonged to a mercenary whofought somewhere in the eastern Mediterraneanregion56. Similar Mediterranean connections are alsosuggested by an iron ladle with a horizontal handle,which was discovered in another warrior grave fromthe Ciumeºti cemetery57 (Fig. 7/3). No analogies madeof iron are known for this object, but a similar ladlemade of silver was found in a grave from ChmyrevaMogila in the northern Pontic region58.

Another quite regular modality of creating andmaintaining an inter-community social network was toconclude matrimonial alliances. For example, Caesar(B.G. I.3; I.18; I.53) provides a series of relevant exam-ples from Late Iron Age Gaul, in which various chief-tains sought to conclude such alliances in order toincrease their authority and prestige.

Along the same lines, it has already been shownthat the Late Iron Age grave from Teleºti in Oltenia(Fig. 8/3) and grave no. 3 from Remetea Mare in theRomanian Banat (Fig. 8/2) provide archaeologicalexamples of such practices. The inventory of the gravefrom Teleºti, including a costume assemblage withmetal fittings of the LT type (enamelled bronze belt,brooches and glass beads), indicates that the deceased

more likely came from the eastern Carpathian Basinand was buried in the cemetery of a Getic communityfrom Oltenia. On the other hand, the original homelandof the woman from Remetea Mare must have been inthe Illyrian or Thracian environment from the south ofthe Danube, due to the funerary rite of inhumation (in acremation cemetery) and the presence of certain specificgrave goods, like the bronze brooch of the “Thracian”type and the segment of a belt with astragals, whichwas reused as a pendant. However, she was buried in aCeltic cemetery in Banat59 (Fig. 8/1).

In both cases, the careful preservation and dis-playing of the jewellery and costume accessories orig-inating from their homeland indicate that these womenenjoyed a privileged status in their adoptive communi-ties, and that their origin was not hidden behind localcostumes. At the same time, the non-local funerary riteand ritual indicate that these women must have beenaccompanied by a “suite” consisting of compatriots,who performed the mortuary ceremonies according tothe prescriptions of their old homeland. Accordingly, a

56 Rustoiu 2006; 2008; 2012b, 159–171.57 Zirra 1967, 24–28, Fig. 11.58 Treister 2010, 11, Fig. 7/5.59 Rustoiu 2004–2005; 2008, 127–132; 2011, 166–168.

STARINAR LXVII/201743

Fig. 7. 1–2) Iron helmet with a bronze bird of prey and Greek bronze greaves, from the burial of a Celtic chieftain at Ciumeºti (after Rustoiu 2008; 2012b); 3) Grave no. 9 at Ciumeºti containing a Mediterranean iron vessel (after Zirra 1967).

Sl. 7. 1–2) Gvozdeni {lem sa bronzanom pticom grabqivicom i gr~ki bronzani {titnici za potkoleniceiz groba keltskog vo|e, ^ume{ti (prema: Rustoiu 2008; 2012b); 3) Grob br. 9 sa mediteranskom gvozdenom posudom, ^ume{ti (prema: Zirra 1967)

31

2

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201744

Fig. 8. 1) Geographic location of the funerary discoveries from Remetea Mare and Teleºti; 2) Grave no. 3 from Remetea Mare; 3) Grave from Teleºti (all after Rustoiu 2004–2005; 2008 etc.)

Sl. 8. 1) Geografska lokacija grobnih nalaza, Remetea Mare i Tele{ti;2) Grob br. 3, Remetea Mare; 3) Grob, Tele{ti (sve prema: Rustoiu 2004–2005; 2008 itd)

2 3

1

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

matrimonial alliance must have implied the mobilityof a larger number of individuals, even if only duringthe lifetime of the woman involved in this relationship.This type of mobility allowed the transmission of somespecific practices, beliefs and ideologies from one com-munity to another, alongside the circulation of severalgoods.

Both the individual mobility and the inter-commu-nity connections very probably contributed to the in-creasing interest in certain LT jewellery, for examplebrooches of the Pestrup type, in the Thracian environ-ment, some of them being very probably manufacturedin workshops in the northern Balkans60. However, suchaccessories were integrated into the costume assem-blages according to the norms of bodily ornamentationspecific to the local communities. For example, thejewellery set from the female grave no. 2 / tumulus no.2 at Seuthopolis contained, alongside two gold Pestruptype brooches, a necklace consisting of bi-truncated orfiligree-decorated gold beads of the local type61 (Fig.9) and two silver brooches of the “Thracian” type62.Furthermore, a similar process has also been noted inthe case of Greek jewellery from the Thracian aristo-cratic environment. According to Milena Tonkova, theconsumers from Thrace selected only Greek jewellerythat corresponded to the symbolic language developedby the local aristocracy, so the decorative repertoirewas different from that encountered in the Greek citieson the Black Sea coast63.

Lastly, artisans played an important role in thespread of certain technologies and types of jewelleryand costume accessories. They were connected or evensubordinated in one way or another to the dominantsocial group of each community. The latter were themain customers, seeking luxurious goods and alsoimposing fashion trends, symbolic meanings and eventhe functional characteristics of different decorativeand utilitarian objects64. At the same time, the artisanswere, in general, a quite mobile social category. Their

60 For the Pestrup type brooches in the northern Balkans seeAnastassov 2006, 14, Fig. 4/5, 7 – distribution map; 2011, 229.

61 Similar beads, albeit made of silver, have also been discov-ered in a grave from Zimnicea, dated to the second half of the 4th

century BC (Alexandrescu 1980, 31, no. 50, fig. 50/9–12) and inanother grave from the LT cemetery at Remetea Mare in Banat,dated to the end of the 4th century and the beginning of the 3rd cen-tury BC (Rustoiu 2008, 115, Fig. 57/2). Furthermore, such piecescontinued to be manufactured and used at the beginning of the 1st

century BC, as their presence in the inventory of the hoard fromKovin in Serbia proves (Ra{ajski 1961, 23, no. 6, Pl. 1/3; Tasi}1992, Pl. 12/42).

62 Dimitrov, i~ikova 1978, 52–53 apudAnastassov 2011, 234,fig. 23; Domaradski 1984, Pl. 33; Emilov 2010, 78 also notes thatthe mentioned brooches, as well as other examples from the region,are elements of some costumes that followed a Hellenistic mannerof expressing status and group identity.

63 Tonkova 1994; 1997a; 1997b; 1999; 2000–2001.64 For the exchange of “desirable goods” amongst these popu-

lations see Egri 2014.

STARINAR LXVII/201745

Fig. 9. Gold necklace and Pestrup type brooches from female grave no. 2/tumulus no. 2 at Seuthopolis (photos Krassimir Georgiev).

Sl. 9. Bro{evi tipa Pestrup i zlatna ogrlicaiz `enskog groba br. 2/tumula br. 2, Sevtopol(fotografije: Krasimira Georgijeva)

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

spatial mobility was mostly determined by the need toreach new customers who were able to place ordersand provide raw materials. Also, the artisans systemat-ically shared specific technological knowledge withinthe same family or group of specialists, and this valu-able information was also transmitted from one gener-ation to another through sets of specific and carefullymaintained practices.

A series of archaeological discoveries from theCarpathian Basin and the northern Balkans illustratesthe artisans’ mobility, as well as the related processesof technological transfer. Some well-known examplesare provided by the hoard from Szárazd–Regöly inHungary, consisting of several gold objects (Fig. 10).Miklós Szabó has noted that the inventory includesboth objects with morphological and technologicalsimilarities in the northern Balkans as early as the5th–3rd centuries BC (tubular elements with filigreedecoration and some types of beads with analogies, forexample, at Mezek or Novi Pazar) and items manufac-tured according to the preferences of the continentalCelts, like the wheel-shaped pieces or the beads deco-rated to resemble human heads65.

Conclusions

Taking into consideration the aforementioned ob-servations resulting from the analysis of archaeologicalevidence, it can be concluded that at least some of thecommunities from the eastern and southern CarpathianBasin and those from the northern Balkans developeda complex network of inter-community relationshipsthat implied different practices and patterns of interac-tion at various social levels. These relationships influen-ced the material culture, the technological knowledgeand the symbolic language of each of the involved par-ties. Among the mechanisms that facilitated these inter-actions were the negotiations and agreements conclud-ed between the leaders of various communities, whichwere commonly accompanied by gift exchangesand/or matrimonial alliances.

At the same time, other forms of individual mobili-ty, for example those practiced by small groups of mer-cenaries, also played an important role in the transmis-

65 Szabó 1975, 152–155, Fig. 7, Pl. 7–10; 1991, 127, Fig. 1–2;2006, 114–115, Fig. 20.

STARINAR LXVII/201746

Fig. 10. Gold artefacts from the hoard uncovered at Szárazd–Regöly and detail of a bead decorated to resemble a human head (after Kovács, Raczky 2000)

Sl. 10. Zlatni artefakti iz ostave otkrivene u Sarazd-Regequi detaq perle ukra{ene qudskim glavama (prema: Kovács, Raczky 2000)

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

sion of some cultural elements from one region toanother. However, in many cases foreign elementswere reinterpreted and adapted according to the visualand symbolic codes specific to each community. Thisphenomenon can be noted, for example, in the case ofsome jewellery sets from the Thracian or the Illyrianenvironment, which integrated a series of elements ofLT origin, or that of some costume assemblages fromthe Carpathian Basin which incorporated jewellery ofsouthern origin. Lastly, the circulation of such objectsand of technological features specific to their manu-facturing in different cultural environments were facil-itated by the spatial mobility of artisans originatingeither from the northern Balkans or the LT environ-ment in the Carpathian Basin.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Milena Tonkova for pro-viding photographs of a series of finds from Bulgariaand for the very useful comments regarding the subject.Many thanks are also owed to Julij Emilov for helpingwith some bibliography and for the numerous usefulcomments, and to Athanasios Sideris for providingcomprehensive information regarding a series of metalvessels. Lastly, other specialists who commented onthe original paper presented in Sofia in 2013 – Maria^i~ikova, Totko Stoyanov and Milo{ Jevti} – are alsokindly acknowledged.

Translated by Mariana Egri

STARINAR LXVII/201747

Starinar is an Open Access Journal. All articles can be downloaded free of charge and used in accordance with the licence Creative Commons – Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Serbia (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/rs/).

^asopis Starinar je dostupan u re`imu otvorenog pristupa. ^lanci objavqeni u ~asopisu mogu se besplatno preuzeti sa sajta ~asopisa i koristiti u skladu sa licencom Creative Commons – Autorstvo-Nekomercijalno-Bez prerada 3.0 Srbija(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/rs/).

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201748

Agre 2011 – D. Agre, The tumulus of Golyamata Mogila nearthe villages of Malomirovo and Zlatinitsa, Avalon Publishing,Sofia.

Alexandrescu 1980 – A. D. Alexandrescu, La nécropoleGète de Zimnicea, Dacia N.S. 24: 19–126.

Alexandrescu 1983 – P. Alexandrescu, Le groupe de trésorsthraces du Nord des Balkans (I), Dacia N. S. 27: 45–66.

Alexandrescu 1984 – P. Alexandrescu, Le groupe de trésorsthraces du Nord des Balkans (II). Dacia N. S. 28: 85–97.

Anastassov 2006 – J. Anastassov, Objets latèniens duMusée de Schoumen (Bulgarie), in: V. Sîrbu, D. L. Vaida(eds.), Thracians and Celts. Proceedings of the InternationalColloquium from Bistriþa, 18–20 May 2006, Editura Mega,Cluj–Napoca: 11–50.

Anastassov 2011 – J. Anastassov, The Celtic presence inThrace during the 3rd century BC in light of new archaeo-logical data, in: M. Gu{tin, M. Jevti} (eds.), The EasternCelts. The communities between the Alps and the Black Sea,Analles Mediterranei, Koper–Beograd: 227–239.

Babeº 1997 – M. Babeº, Despre fortificaþiile “Cetãþii Jido-vilor” de la Coþofenii din Dos. Studii ºi cercetãri de istorieveche ºi arheologie 48: 199–236.

Babi} 2002 – S. Babi}, ‘Princely graves’ of the CentralBalkans – a critical history of research. European Journal ofArchaeology 5 (1): 68–86.

Bader 1984 – T. Bader, O zãbalã din a doua perioadã aepocii fierului descoperitã la Ciumeºti, Studii ºi cercetãri deistorie veche ºi arheologie 35, 1: 85–90.

Berciu 1967 – D. Berciu, Les Celtes et la civilisation de LaTène chez les Géto-Dace, Bulletin of the Institute of Archa-eology London 6: 75–93.

Boteva 2002 – D. Boteva, An attempt at identifyingAlexander’s route towards the Danube in 335 BC, in: K.Bo{nakov, D. Boteva (eds.), Jubilaeus V. Sbornik v ~est naprof. Margarita Ta~eva, Univ. Sv. Kliment Ochridski, Sofia:27–31.

Bouzek 2005 – J. Bouzek, Celtic campaigns in southernThrace and the Tylis kingdom: The Duchov fibula inBulgaria and the destruction of Pistiros in 279/8 BC, in: H.Dobrzanska, V. Megaw, P. Poleska (eds.), Celts on the mar-gin. Studies in European cultural interaction (7th century BC– 1st century AD) dedicated to Zenon Wozniak, Institute ofArchaeology and Ethnology, Krakow: 93–101.

Bouzek 2006 – J. Bouzek, Celts and Thracians, in: V. Sîrbu,D. L. Vaida (eds.), Thracians and Celts. Proceedings of theInternational Colloquium from Bistriþa, 18–20 May 2006,Editura Mega, Cluj–Napoca: 77–92.

Bujna 1995 – J. Bujna, Malé Kosihy. Latènezeitliches Gräber-feld. Katalog, Instituti Archaeologici Nitriensis, Nitra.

Bujna 2005 – J. Bujna, Kruhovy {perk z laténskych `enskyhrobov na Slovensku, Instituti Archaeologici Nitriensis, Nitra.

^i~ikova 1984 – M. ^i~ikova, Anti~na keramika, in:D. Dimitrov, M. ^i~ikova, A. Balkanska, L. Ognenova-Marinova (red.), Sevmonolis, t. I., Sofia 1984: 18–113(M. Chichikova, Antichna keramika, in: D. Dimitrov, M.Chichikova, A. Balkanska, L. Ognenova-Marinova (red.),Sevtopolis, t. I., Sofiia 1984: 18–113).

^i~ikova 1992 – M. ^i~ikova, The Thracian tomb nearSveshtari. Helis 2: 143–163.

Daicoviciu 1972 – H. Daicoviciu, Dacia de la Burebista lacucerirea romanã, Editura Dacia, Cluj.

Dimitrov, ^i~ikova 1978 – D. Dimitrov, M. ^i~ikova, TheThracian City of Seuthopolis, BAR Supplementary Series38, Oxford.

Dietler 2005 – M. Dietler, The archaeology of colonizationand the colonization of archaeology. Theoretical challengesfrom an ancient Mediterranean colonial encounter, in: G. J.Stein (ed.), The Archaeology of Colonial Encounters: Com-parative Perspectives, School of American Research Press,Santa Fe (NM): 33–68.

Domaradski 1984 – M. Domaradski, Kelmime na Bal-kanskiý noluosmrov, Sofia 1984 (M. Domaradski, Keltitena Balkanskiia poluostrov, Sofiia 1984).

D`ino 2007 – D. D`ino, The Celts in Illyricum – whoeverthey may be: the hybridization and construction of identitiesin Southeastern Europe in the fourth and third centuries BC,Opuscula Archaeologica 31: 49–68.

Dzino, Domi} Kuni} 2012 – D. Dzino, A. Domi} Kuni},Pannonians: Identity-perceptions from the Late Iron Age toLater Antiquity, in: B. Migotti (ed.), The archaeology ofRoman southern Pannonia. The state of research and selectedproblems in the Croatian part of the Roman province of Pan-nonia, BAR International Series 2393, Oxford: 93–115.

Egri 2014 – M. Egri, Desirable goods in the Late Iron Age– The craftsman’s perspective, in: S. Berecki (ed.), Iron AgeCrafts and Craftsmen in the Carpathian Basin. Proceedingsof the International Colloquium from Târgu Mureº, 10–13October 2013, Editura Mega, Târgu Mureº: 233–248.

Emilov 2007 – J. Emilov, La Tene finds and the indigenouscommunities in Thrace, Interrelations during the Hellenisticperiod, Studia Hercynia 11: 57–75.

Emilov 2010 – J. Emilov, Ancient texts on the Galatian royalresidence of Tylis and the context of La Tène finds in south-ern Thrace. A reappraisal, in: L. F. Vagalinski (ed.), In search

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

of Celtic Tylis in Thrace (III C BC), Bulgarian Academy ofSciences, Sofia: 67–87.

Ferencz 2007 – I. V. Ferencz, Celþii pe Mureºul mijlociu. LaTène-ul timpuriu ºi mijlociu în bazinul mijlociu al Mureºului(sec. IV–II î.Chr.), Bibliotheca Brukenthal XVI, Sibiu.

Fol et al. 1986 – A. Fol, M Chichikova, T. Ivanov, T. Teo-filov, The Thracian tomb near the village of Sveshtari, SvyatPublishers, Sofia.

Given 2004 – M. Given, The Archaeology of the Colonized,Routledge, London.

Gosden 2004 – C. Gosden, Archaeology and Colonialism.Cultural Contact from 5000 BC to the Present, CambridgeUniversity Press, Cambridge.

Gu{tin 2002 – M. Gu{tin, I Celti dell’Adriatico. Carni trafonti storiche e archeologia, in: Gli echi della Terra. Presenzeceltiche in Friuli: dati materiali e momenti dell’immaginario.Convegno di studi, Giardini editori, Pisa–Roma: 11–20.

Gu{tin, Kuzman 2016 – M. Gu{tin, P. Kuzman, The elite.The upper Vardar river region in the period from the reign ofPhilip II of Macedon until the reign of Diadochi, in: V. Sîrbu,M. Jevti}, K. Dmitrovi}, M. Lju{tina (eds.), Funerary Practi-ces during the Bronze and the Iron Ages in the Central andSoutheast Europe, Proceedings of The 14th InternationalColloquium of Funerary Archaeology, ^a~ak, Serbia,24th–27th September 2015, ^a~ak – Beograd: 313–332.

Iliescu 1990 – V. Iliescu, Alexander der Grosse undDromichaites, in: M. Ta~eva, D. Bojad`iev (eds.), Studia inHonorem Borisi Gerov, Sofia Press, Sofia: 101–113.

Kovács, Raczky 2000 – T. Kovács, P. Raczky, A MagyarNemzeti Múzeum oskori aranykincsei, Magyar NemzetiMuzeum, Budapest.

Kruta 2000 – V. Kruta, Les Celtes. Histoire et dictionaire.Des origines à la romanisation et aux christianisme, Laffont,Paris.

Kull 1997 – B. Kull, Tod und Apotheose. Zur Ikonographiein Grab und Kunst der jüngeren Eisenzeit an der unterenDonau und ihrer Bedeutung für die Interpretation von„Prunkgräbern”. BerichtRGK 78: 197–466.

Mãndescu 2010 – D. Mãndescu, Cronologia perioadeitimpurii a celei de a doua epoci a fierului (sec. V–III a.Chr.)între Carpaþi, Nistru ºi Balcani, Editura Istros, Brãila.

Medeleþ 1982 – F. Medeleþ, În legãturã cu expediþiaîntreprinsã de Alexandru Macedon la Dunãre în 335 î.e.n.,Acta Musei Napocensis 19: 13–22.

Medeleþ 2002 – F. Medeleþ, Über den Feldzug Alexandersdes Grossen an die Donau im Jahr 335 v. Chr., in: K. Bo{na-kov, D. Boteva (eds.), Jubilaeus V. Sbornik v ~est na prof.Margarita Ta~eva, Univ. Sv. Kliment Ochridski, Sofia:272–279.

Medeleþ ms – F. Medeleþ, Necropola La Tène de la RemeteaMare (jud. Timiº), Manuscript.

Megaw 1970 – J. V. S. Megaw, Art of the European IronAge. A study of the elusive image, Adams & Dart, Bath.

Megaw 2004 – J. V. S. Megaw, In the footsteps of Brennos?Further archaeological evidence for Celts in the Balkans, in:B. Hänsel, E. Studeníková (eds.), Zwischen Karpaten undÄgäis. Neolitikum und ältere Bronzezeit. Gedenkschrift fürV. Nêmejcová-Pavúková, Verlag Marie Leidorf, Rahden/Westf.: 94–107.

Megaw, Megaw 2001 – R. Megaw, V. Megaw, Celtic Art.From its beginnings to the Book of Kells. Revised andexpanded edition, Thames & Hudson, New York.

Mitrevski 2011 – D. Mitrevski, The treasure from Tremnikand some traces of the Celts in the Vardar valley, in: M.Gu{tin, M. Jevti} (eds.), The Eastern Celts. The communitiesbetween the Alps and the Black Sea, Analles Mediterranei,Koper–Beograd: 199–206.

Moreau 1958 – J. Moreau, Die Welt der Kelten, PhaidonVerlag Sammlung Klipper, Stuttgart.

Moscalu 1989 – E. Moscalu, Die thrako-getische Fürsten-grab von Peretu in Rumänien. BerichtRGK 70: 129–90.

Nawotka 2010 – K. Nawotka, Alexander the Great,Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge.

Németi 2012 – J. Németi, Celtic grave from Moftinu Mic,Satu Mare County, Marisia 32: 71–77.

Papazoglu 1978 – F. Papazoglu, The Central Balkan Tribesin Pre-Roman Times, Hakkert, Amsterdam.

Pârvan 1926 – V. Pârvan, Getica. O protoistorie a Daciei,Cultura naþionalã, Bucureºti.

Popovi} 2005 – P. Popovi}, Kale–Kr{evica: investigations2001–2004. Interim report, Zbornik Narodnog muzeja 18, 1:141–174.

Popovi} 2006 – P. Popovi}, Central Balkans between theGreek and Celtic world: case study Kale–Kr{evica, in: N.Tasi}, C. Grozdanov (eds.), Homage to Milutin Gara{anin,Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts-Macedonian Academyof Sciences and Arts, Belgrade: 523–536.

Popovi} 2007a – P. Popovi}, Numismatic finds of the4th–3rd centuries BC from Kale at Kr{evica (south-easternSerbia), Arheolo{ki vestnik 58: 411–417.

Popovi} 2007b – P. Popovi}, Kr{evica et les contacts entrel’Egée et les centres des Balkans, Histria Antiqua 15:125–136.

Popovi}, Vrani} 2013 – P. Popovi}, I. Vrani}, One possiblelocation of Damastion–Kale by Kr{evica (south-eastern Ser-bia), in: G. R. Tsetskhladze et al. (eds.), The Bosporus:Gateway between the Ancient West and East (1st Millennium

STARINAR LXVII/201749

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

BC – 5th Century AD). Proceedings of the Fourth Internati-onal Congress on Black Sea Antiquities. Istanbul, 14th–18th

September 2009, BAR International Series 2517, Oxford:309–313.

Potrebica, Dizdar 2012 – H. Potrebica, M. Dizdar, Celtsand La Tène Culture – a view from the periphery, in: R. Karl,J. Leskovar, S. Moser (eds.), Die erfundenen Kelten. Mytho-logie eines Begriffes und seine Verwendung in Archäologie,Tourismus und Esoterik. Interpretierte Eisenzeiten. Tagungs-beiträge der 4. Linzer Gespräche zur interpretativen Eisen-zeitarchäologie, Studien zur Kulturgeschichte vonOberösterreich 31, Linz: 165–172.

Ra{ajski 1961 – R. Ra{ajski, Da~ka srebrna ostava izKovina, Rad Vojvodanskih Muzeja 10: 7–24.

Rustoiu 2002 – A. Rustoiu, Habitat und Gesellschaft im4.–2- Jh. v. Chr., in: A. Rustoiu et al., Habitat und Gesell-schaft im westen und nordwesten Rumäniens vom Ende des2. Jahrt. V. Chr. zum Anfang des 1. Jhrt. N. Chr, Napoca Star,Cluj–Napoca, 2002, 49–90.

Rustoiu 2004–2005 – A. Rustoiu, Celtic-indigenous con-nections in Oltenia during middle La Tène. Observationsconcerning a Celtic grave from Teleºti, Ephemeris Napocensis14–15: 53–71.

Rustoiu 2006 – A. Rustoiu, A Journey to Mediterranean.Peregrinations of a Celtic Warrior from Transylvania, StudiaUniversitatis “Babeº–Bolyai”. Historia. Special Issue: Fo-cusing on Iron Age Elites 51, 1: 42–85.

Rustoiu 2008 – A. Rustoiu, Rãzboinici ºi societate în ariacelticã transilvãneanã. Studii pe marginea mormântului cucoif de la Ciumeºti, Editura Mega, Cluj–Napoca.

Rustoiu 2011 – A. Rustoiu, The Celts from Transylvaniaand the eastern Banat and their southern neighbours.Cultural exchanges and individual mobility, in: M. Gu{tin,M. Jevti} (eds.), The Eastern Celts. The communitiesbetween the Alps and the Black Sea, Analles Mediterranei,Koper–Beograd: 163–170.

Rustoiu 2012a – A. Rustoiu, The Celts and indigenous pop-ulations from the southern Carpathian Basin. Intercommu-nity communication strategies, in: S. Berecki (ed.), Iron Agerites and rituals in the Carpathian Basin. Proceedings of theInternational Colloquium from Târgu Mureº, 7–9 October2011, Editura Mega, Cluj–Napoca – Târgu Mureº: 357–390.

Rustoiu 2012b – A. Rustoiu, Commentaria Archaeologicaet Historica (I). 1. The grave with a helmet from Ciumeºti –50 years from its discovery. Comments on the greaves. 2.The Padea-Panagjurski kolonii group in Transylvania. Oldand new discoveries, Ephemeris Napocensis 22: 159–183.

Rustoiu 2013 – A. Rustoiu, Celtic lifestyle – indigenousfashion. The tale of an Early Iron Age brooch from the north-western Balkans, Archaeologia Bulgarica 17, 3: 1–16.

Rustoiu 2014 – A. Rustoiu, Indigenous and colonist com-munities in the eastern Carpathian Basin at the beginning ofthe Late Iron Age. The genesis of an Eastern Celtic World,in: C. N. Popa, S. Stoddart (eds.), Fingerprinting the Iron Age.Approaches to identity in the European Iron Age. IntegratingSouth-Eastern Europe into the debate, Oxbow Books, Oxford:142–156.

Rustoiu, Berecki 2012 – A. Rustoiu, S. Berecki, “Thracian”warriors in Transylvania at the beginning of the Late IronAge. The grave with Chalcidian helmet from Ocna Sibiului,in: S. Berecki (ed.), Iron Age rites and rituals in the Carpa-thian Basin. Proceedings of the International Colloquiumfrom Târgu Mureº, 7–9 October 2011, Editura Mega,Cluj–Napoca – Târgu Mureº: 161–82.

Rustoiu, Berecki 2016 – A. Rustoiu, S. Berecki, Culturalencounters and fluid identities in the eastern CarpathianBasin in the 4th–3rd centuries BC, in: I. Armit, H. Potrebica,M. ^re{nar, P. Mason, L. Büster (eds.), Cultural encountersin Iron Age Europe, Archaeolingua, Budapest: 285–304.

Rustoiu, Egri 2011 – A. Rustoiu, M. Egri, The Celts fromthe Carpathian Basin between continental traditions and thefascination of the Mediterranean. A study of the Danubiankantharoi, Editura Mega, Cluj–Napoca.

Rustoiu,Ursuþiu 2013 – A. Rustoiu, A. Ursuþiu, Celtic colo-nization in Banat. Comments regarding the funerary discov-eries, in: V. Sîrbu, R. ªtefãnescu (eds.), The Thracians andtheir neighbours in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Proceedingsof the 12th International Congress of Thracology. Târgoviºte10th–14th September 2013. “Necropolises, cult places, reli-gion, mythology”, Volume II, Editura Istros, Braºov: 323–345.

Rusu 1969 – M. Rusu, Das keltische Fürstengrab vonCiumeºti in Rumänien, BerichtRGK 50: 267–300.

Schaaff 1974 – U. Schaaff, Keltische Eisenhelme aus vor-römischer Zeit, JRGZM 21, 1: 149–204.

Schaaff 1988 – U. Schaaff, Keltische Helme, in: AntikeHelme. Sammlung Lipperheide, RGK, Mainz: 293–317.

Sîrbu 2006 – V. Sîrbu, Man and Gods in the Geto-DacianWorld, Muzeul Judetean de Istorie, Braºov.

Sîrbu, Florea 2000 – V. Sîrbu, G. Florea, Les Géto-Daces.Iconographie et imaginaire. Fondation Culturelle Roumaine,Cluj–Napoca.

Szabó 1975 – M. Szabó, Sur la question de filigrane dansl’art des celtes orientaux, in: J. Fitz (ed.), The Celts in CentralEurope, Alba Regia, Székesfehérvár: 147–165.

Szabó 1991 – M. Szabó, Thraco-Celtica, Orpheus 1: 126–134.

Szabó 1992 – M. Szabó, Les Celtes de l’Est. Le Second Agedu Fèr dans la cuvette des Karpates, Errance, Paris.

Szabó 2006 – M. Szabó, Les Celtes de l’Est, in: M. Szabó(ed.), Celtes et Gaulois. L’Archéologie face à L’Histoire.

STARINAR LXVII/201750

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

Les Civilisés et les Barbares du Ve au IIe siècle avant J.-C.Actes de la table ronde de Budapest 17–18 juin 2005, Colle-ction Bibracte 12/3, Glux-en-Glenne: 97–117.

Tankó, Tankó 2012 – É. Tankó, K. Tankó, Cremation anddeposition in the Late Iron Age cemetery at Ludas, in: S.Berecki (ed.), Iron Age rites and rituals in the CarpathianBasin. Proceedings of the International Colloquium fromTârgu Mureº, 7–9 October 2011, Editura Mega, Cluj–Napoca– Târgu Mureº: 249–258.

Tasi} 1992 – N. Tasi} (ed.), Scordisci and the native popu-lation in the Middle Danube Region, Belgrade.

Theodossiev 2005 – N. Theodossiev, Celtic settlement innorth-western Thrace during the late fourth and third cen-turies BC: Some historical and archaeological notes, in: H.Dobrzanska, V. Megaw, P. Poleska (eds.), Celts on the mar-gin. Studies in European cultural interaction (7th century BC– 1st century AD) dedicated to Zenon Wozniak, Institute ofArchaeology and Ethnology, Krakow: 85–92.

Tonkova 1994 – M. Tonkova, Vestiges d’ateliers d’orfèvreriethrace des Ve–IIIe s. av. J.-C. sur le territoire de la Bulgarie,Helis 3: 175–200.

Tonkova 1997a – M. Tonkova, Hellenistic jewellery fromthe colonies on the West Black Sea Coast, Archaeology inBulgaria 1, 1: 83–102.

Tonkova 1997b – M. Tonkova, Traditions and Aegean influ-ences on the jewellery of Thracia in the early Hellenistictimes, Archaeologia Bulgarica 2: 18–31.

Tonkova 1999 – M. Tonkova, L’orfèvrerie en Thrace auxVe–IVe s. av. J.-C. Gisements d’or et d’argent, ateliers,parures, in: A. Müller et al. (eds.), Thasos. Matièrespremières et technologie de la préhistoire à nos jours. Actesdu Colloque International 26–29/9/1995, Thasos–Liménaria,Diffusion de Boccard, Athènes–Paris: 185–194.

Tonkova 2000–2001 – M. Tonkova, Classical jewellery inThrace: origins and development, archaeological contexts,Talanta 32–33: 277–288.

Treister 2010 – M. Treister, Bronze and silver Greek,Macedonian and Etruscan vessels in Scythia, Bolletino diArcheologia on line 2010, Volume speciale C/C10/2: 9–26.

Tsetskhladze 1998 – G. Tsetskhladze, Who built the Sky-thian and Thracian royal and elite tombs? Oxford Journal ofArchaeology 17(1): 55–92.

Turcu 1979 – M. Turcu, Geto-dacii din Cîmpia Munteniei,Editura ªtiinþificã ºi Enciclopedicã, Bucureºti.

Vrani} 2014 – I. Vrani}, ‘Hellenization’ and ethnicity in thecontinental Balkan Iron Age, in: C. N. Popa, S. Stoddart(eds.), Fingerprinting the Iron Age. Approaches to identity inthe European Iron Age. Integrating South-Eastern Europeinto the debate, Oxbow Books, Oxford: 161–172.

Vulpe 1988 – A. Vulpe, Istoria ºi civilizaþia Daciei în sec.IX–IV î.e.n., in: V. Dumitrescu, A. Vulpe, Dacia înainte deDromihete, Editura ªtiinþificã ºi Enciclopedicã, Bucureºti.

Vulpe 2001 – A. Vulpe, Istoria ºi civilizaþia spaþiuluicarpato-dunãrean între mijlocul sec. al VII-lea ºi începutulsec. al III-lea a.Chr., in: M. Petrescu-Dîmboviþa, A. Vulpe,(eds.), Istoria Românilor, vol. 1, Editura Enciclopedicã,Bucureºti: 451–500.

Vulpe, Zahariade 1987 – A. Vulpe, M. Zahariade, Geto-Dacii în istoria militarã a lumii antice, Editura Militarã,Bucureºti.

Vulpe 1966 – R. Vulpe, Aºezãri getice din Muntenia,Editura Meridiane, Bucureºti.

Werner 1988 – W. M. Werner, Eisenzeitliche Trensen an derunteren und mittleren Donau, PBF XVI/4, München.

Yordanov 1992 – K. Yordanov, The march of Alexander theGreat into Thrace, Bulgarian Historical Review 4: 11–32.

Zaninovi} 2001 – M. Zaninovi}, Jadranski Kelti, OpusculaArchaeologica 25: 57–63.

Zirra 1967 – V. Zirra, Un cimitir celtic în nord-vestulRomâniei, Muzeul Regional Maramureº, Baia Mare.

Zirra 1976 – V. Zirra, La nécropole La Tène d’Apahida.Nouvelles considerations, Dacia N.S. 20: 129–165.

Zirra 1981 – V. Zirra, Latènezeitlichen Trense in Rumänien,Hamburger Beitr. f. Arch. 8: 115–171.

STARINAR LXVII/201751

Aurel RUSTOIU

Thracians – Illyrians – Celts. Cultural Connections in the Northern Balkans in the 4th–3rd Centuries BC (33–52)

STARINAR LXVII/201752

Tokom IV i po~etkom III veka pre n.e. Karpatski basen be-le`i pro{irewe oblasti u kojoj su `ivele keltske zajedni-ce – na istok i na zapad. Rezultat tih naseqavawa bila jepojava nekih novih zajednica koje je karakterisalo kultur-no stapawe doseqenika sa doma}im stanovni{tvom, {to jedovelo do stvarawa novog identiteta zajednica. Istovreme-no, do{qaci su uspostavqali razli~ite odnose (dru{tvene,politi~ke, ekonomske itd.) sa susednim balkanskim sta-novni{tvom. U ovom ~lanku govorimo o praksi u vezi s kul-turnim interakcijama pomenutih zajednica, kao i o na~ini-ma pomo}u kojih se ti odnosi mogu identifikovati putemanalize materijalne kulture isto~ne i ju`ne oblasti Kar-patskog basena, kao i severnog i severozapadnog Balkana.

Ovi mehanizmi interakcije me|u zajednicama omogu-}ili su stvarawe nekih slo`enih dru{tvenih mre`a kojesu ure|ivale odnose izme|u raznih etni~kih i dru{tvenihgrupa Karpatskog basena i severnog Balkana. Tu mo`emopomenuti i pregovore i dogovore izme|u vo|a razli~itih za-

jednica, uz razmenu poklona i sklapawe brakova. Opticajnekih artefakata, poput ~uvenih zlatnih grivni iz GorwegCibara, ili |ema sa severnog Balkana, na|enih u latenskomgrobqu u ^ume{tiju, kao i neki pogrebni ostaci otkrive-ni na teritoriji Rumunije, mogu biti protuma~eni uzima-wem u obzir pomenutih mehanizama. Istovremeno, zna~ajnuulogu u prenosu pojedinih elemenata kulture iz jedne obla-sti u drugu imalo je kretawe pojedinaca. Me|utim, tu|ielementi bivali su reinterpretirani i prilago|avani uskladu s vizuelnim i simboli~kim kodom specifi~nim zasvaku zajednicu. Ovaj fenomen mo`e sezapaziti, na pri-mer, u slu~aju odre|enih setova nakita iz tra~anske iliilirske sredine koji sadr`e niz elemenata latenskog tipa,ili ode}e Karpatskog basena sa ju`wa~kim nakitom. Naj-zad, opticaj takvih predmeta i wihova proizvodwa u razli-~itim kulturnim sredinama omogu}eni su kretawem i ra-dom pojedinih zanatlija kako sa severa Balkana, tako i izlatenske sredine Karpatskog basena.

Kqu~ne re~i. – Tra~ani, Iliri, Kelti, Karpatski basen, severni Balkan, Aleksandar Veliki, latenska kultura, pogrebni obi~aji.

Rezime: AUREL RUSTOJU, Institut arheologije i istorije umetnosti, Klu`–Napoka, Rumunija

TRA ANI – ILIRI – KELTI.KULTURNE VEZE NA SEVERNOM BALKANU U IV I III VEKU PRE NOVE ERE