This work is published under the responsibility of the ... · traded raw materials in both the...

Transcript of This work is published under the responsibility of the ... · traded raw materials in both the...

This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and the arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries.

This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries, and to the name of any territory, city or area.

Statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

The publication of this document has been authorised by Ken Ash, Director of the Trade and Agriculture Directorate

Photo credit: Jukree © Thinkstock

© OECD (2014)

You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgment of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to

FOREWORD – 3

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

Foreword

Trade policy discussions and negotiations have long taken aim at removing import restrictions to enable greater access to markets. In recent years their focus has widened. Growing global demand for raw materials and increasing resort to export restrictions has forced governments and other stakeholders to pay close attention to conditions of supply and the adverse effects of government restrictions on exports in this sector and look for ways of placing greater controls on their use.

This volume brings together different strands of analysis carried out by OECD since 2009 on the use of export restrictions in the trade of raw materials. The aim is to contribute to an informed policy dialogue among countries that irrespective of whether they apply export restrictions or not, all rely on a well-functioning global market for at least some of the raw materials needs of their industries. Some of the analysis presented here has been published as individual working papers. But as the saying goes, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and it is hoped that this volume will provide the reader with a thorough understanding of how export restrictions affect economies with international supply chains and what could constitute possible actions leading to greater restraint in the use of such measures.

In addition to the authors of the chapters, many other individuals have contributed to the work published here. Overall management is provided by Ken Ash, OECD Director for Trade and Agriculture, and Raed Safadi, OECD Deputy Director for Trade and Agriculture. Collecting the data for the OECD Inventory of Export Restrictions would not have been possible without the collaboration of individuals and government officials in the countries surveyed. The OECD’s work on export restrictions in raw materials trade is directed by Frank van Tongeren, Head of the Division on Policies in Trade and Agriculture. The analysis leading to the various chapters was conducted under the guidance of the OECD Trade Committee and its Working Party, which along with the OECD Business and Industry Advisory Committee and the participants of two multi-stakeholder OECD workshops held in 2009 and 2012 provided valuable data, observations and comments at different stages. Barbara Fliess was the project manager for this publication. Alison Burrell edited the volume and Michèle Patterson coordinated its production.

TABLE OF CONTENTS – 5

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

Table of contents

Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 9

Part I. Trends in the Trade of Raw Materials

Chapter 1. Recent developments in the use of export restrictions in raw materials trade by Barbara Fliess, Christine Arriola and Peter Liapis ............................................................................ 17

Part II. Economic Effects of Export Restrictions

Chapter 2. Economics of export restrictions as applied to industrial raw materials by K.C. Fung and Jane Korinek ............................................................................................................. 63

Chapter 3. Effects of removing export taxes on steel and steel-related raw materials by Frank van Tongeren, James Messent, Dorothee Flaig, and Christine Arriola ................................. 93

Chapter 4. How export restrictive measures affect trade in agricultural commodities by Peter Liapis ..................................................................................................................................... 115

Part III. Approaches for Enhanced Control and More Transparent Use of Export Restrictions

Chapter 5 Multilateralising regionalism: Disciplines on export restrictions in regional trade agreements by Jane Korinek and Jessica Bartos ................................................................................................... 149

Chapter 6. Increasing the transparency of export restrictions: Benefits, good practices and a practical checklist by Barbara Fliess and Osvaldo R. Agatiello ........................................................................................ 183

Chapter 7. Mineral resource policies for growth and development: Good practice examples by Jane Korinek ................................................................................................................................... 225

ACRONYMS – 7

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

Acronyms

ADA Anti-Dumping Agreement

AMIS Agricultural Market Information System

APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

BACI Base pour l’Analyse du Commerce International

CEPII Centre d'Etudes Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales

c.i.f. cost, insurance, freight

DDA Doha Development Agenda

EFTA European Free Trade Area

EITI Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative

f.o.b. free on board

FYROM Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

GAPP Generally Accepted Principles And Practices

GATT General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

GRB Government of the Republic of Botswana

HHI Hirschman-Herfindahl index

HS Harmonised System (Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System)

IMF International Monetary Fund

MEP minimum export price

MFDP Ministry of Finance and Development Planning (Botswana)

MOFCOM Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China

PPI Policy Perception Index

RTA regional trade agreement

SACU South African Customs Union

SCM Subsidies and Countervailing Measures

SDT Special and Differential treatment

SOE state-owned enterprise

SWF sovereign wealth fund

t ton; metric weights and measures are used throughout the volume

URAA Uruguay Round Agreement on Agriculture

USD United States Dollar

WCO World Customs Organisation

WTO World Trade Organisation

OVERVIEW – 9

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

OVERVIEW

Introduction

This volume uses multiple approaches to examine world trade in raw materials. “Raw materials”, for the purpose of this publication, comprise the minerals and metals that are crucial inputs for the capital and consumer goods industries around the world, and the agricultural commodities that supplement domestic food supplies in many countries and sustain the global food processing industry. Virtually all countries need access to many or most of these raw materials for core economic activities and to sustain a healthy, well-nourished population.

As no country is self-sufficient in every raw material, it follows that virtually all countries are vulnerable to any attempt to restrict the export of at least some commodities. However, notwithstanding that resource nationalism is increasingly at odds with the interdependence of economies in the 21

st century, the last decade has seen a marked expansion in efforts to regulate

the supply and export flows of these materials through the use of export restrictions around the globe.

In the face of this trend, the issue of export restrictions on raw materials has raised concern within industry and government circles. While some restrictions were put in place in reaction to the strong demand and rising prices of commodities prior to the international financial crisis, or to the sudden demand surges and price peaks in agricultural commodities that accompanied the crisis, others have since followed and many are still in place. Export restrictions have contributed to episodes of global supply shortages and strong swings in prices. They have also become a source of friction and open trade disputes among governments using them and trading partners affected by them. All these developments make raw material export restrictions and other forms of resource protectionism a global challenge that calls for well informed and coordinated responses.

Against this background, the OECD initiated a programme of work in 2009 designed to study these restrictive measures and their economic effects, and to facilitate dialogue among stakeholders directly or indirectly affected by them. The programme has focused on export restrictions affecting, in particular, industrial raw materials. Two workshops were organised.

1 The

first major publication of the programme2

contains a selection of the papers from the first of these workshops.

Since then, the programme has continued to place its work in the public domain via a number of OECD Trade Policy Papers, on which some of the chapters in this volume draw heavily. Other parts of this volume constitute new work that is published here for the first time. The reader should be aware that the work presented in this volume is not concerned with import policies and restrictions on imports. There has been considerable work on import barriers, some of which contributed directly to securing the strong disciplines on imports currently enshrined in WTO legal texts, and this work continues. It is not, however, reflected in this publication.

Some of the chapters make use of a unique new database, the OECD Inventory of Restrictions on Trade in Raw Materials (OECD, 2014) (or, for short in this volume, the OECD Inventory). Set up in 2009 to overcome the dearth of systematically compiled information on export restrictions for raw materials, it covers both industrial raw materials and agricultural commodities. It compiles annual information, from 2007 onwards, on the complete range of export restraint instruments as applied by a large number of exporting countries to the main relevant, internationally

10 – OVERVIEW

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

traded raw materials in both the industrial and agricultural categories. Much of the analysis and discussion assembled in the present volume makes use of the information contained in the Inventory.

The chapters are organised in three parts. Part 1 consists of a single chapter, which presents global trends in the use of export restrictions, broken down by exporting country, type of instrument and type of raw material. It documents how, for the vast majority of these commodities, the high concentration of supply or at least of exportable surpluses imparts an oligopolistic structure to the corresponding world market for that commodity. This creates the conditions in which individual large exporters may perceive an incentive to use their leverage over the world market to pursue domestic, or at least country-specific, policy objectives by manipulating the flow of this product onto the world market. The chapter also analyses the information recorded in the Inventory on the reasons given by individual countries for their use of export restrictions. Additional useful components of this chapter are a detailed description of the structure and coverage of the Inventory, a brief overview of current multilateral disciplines concerning export restrictions and some specific examples of their use by particular countries for certain products, together with some specific consequences of these policy choices. Thus, the chapter sets the scene for the rest of the volume, and justifies – albeit implicitly – the various analytical and conceptual approaches taken in subsequent chapters.

Part II consists of three chapters that explore the trade and welfare effects of export restrictions from different perspectives. Chapter 2 uses an economic theory framework to predict the effects of an export restriction on trade flows, world market and domestic prices, and the market outcomes for trading partners, including both exporters of the commodity whose exports are restricted and net-importing countries. Two restrictive instruments – a tax and a quota – are analysed. Welfare transfers and net losses generated by the restriction are also identified. The economic models used are designed to depict the oligopolistic nature of world markets for industrial raw materials. This represents the first time such a model has been used in this precise context. The insights gained from the theoretical analysis are then used to consider whether, and if so in which circumstances, export restrictions might in fact be effective in achieving any of the objectives countries have claimed for their use.

Chapter 3 reports the results of an empirically-based simulation exercise focussing on the global steelmaking industry and the world market for steel. This is an industry where both import protection on the final product and export restrictions on raw materials used as inputs are very prevalent. Using information on export taxes from the OECD Inventory and the OECD Trade Model, it examines the global effects of removing all export taxes currently applied on steel and the main raw materials used in steel production: scrap and ferrous waste, iron ore, and coke. For the most part, the simulated impacts on world market are strongly consistent with the predictions made in Chapter 2. Furthermore, the multilateral policy change that is simulated for just a few sectors and involving relatively few countries nonetheless gives an important boost to global trade. An important finding is that – contrary to widespread belief – export taxes and other export restrictions do not necessarily benefit domestic downstream industries or enhance the domestic value-adding process.

Chapter 4 uses various empirical approaches to capture the effects of recent agricultural export restrictions during 2004 to 2011 on (inter alia) world market prices, on global exports of the product whose exports are restricted, and on the country-specific export prices and exported quantities of certain commodities whose imports are restricted. The results are mixed and for the most part inconclusive. There is some evidence that the use of restrictions on rice exports reduced the exports of the restricting countries and importers diversified sourcing partners, but these effects were not found for two other crops, wheat and maize.

In summary, the two empirical chapters in Part II provide some real-world support for the effects predicted by the theoretical analysis in Chapter 2. The results presented here should not be taken as the final word, as other approaches, longer time series, and more probing statistical approaches are yet to be tried.

OVERVIEW – 11

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

Part III consists of four chapters that address the general question: where do we go from here? How can the international community respond to the challenge of improving mutually agreed disciplines in this area, and what can be learned from any progress made so far? As part of the answer, Chapter 5 documents in detail the successes achieved by various regional trade agreements (RTAs) in going beyond the current state of discipline achieved within the WTO. The extent of agreed disciplines in the WTO as regards export restrictions is much less as compared with disciplines on imports. The Chapter first examines the multilateral rules that have been agreed in this area. It then underlines what has been possible within a smaller negotiating group of interested parties within RTAs. What is particularly enlightening is the array of novel strategies and procedures adopted by some of these RTAs for strengthening their disciplines on export restrictions.

Chapter 6 implicitly recognises that robust multilateral disciplines (as currently exist with respect to restrictions on imports) will not be achieved overnight, and explores ways in which, in the meantime, some of the more damaging consequences for stakeholders of the current use of export restrictions can be reduced by the adoption of certain transparency rules governing the design, development and implementation of export restrictions. Undoubtedly, the benefits of greater policy transparency for all those involved, including the policy-setting governments themselves, go well beyond the context of export restrictions and apply across the whole policy spectrum. This chapter, however, keeps its focus closely on the export restriction issue, and shows how well-defined transparency protocols, set out in detail in a transparency checklist, can greatly assist those operating in markets subject to the unpredictability and potential instability that are provoked by the way many export restrictions are currently used.

Finally, Chapter 7 looks in great detail at two success stories provided by Chile’s management of its copper industry, and Botswana’s steering of its mineral industry (principally diamonds) as an engine of growth and development for the economy as a whole. This chapter provides conclusive evidence that the objectives stated by many export-restricting countries to justify the use of this set of trade instruments can be achieved more efficiently and more sustainably over the longer term by quite different policy approaches, which leave their export flows unimpeded. An important common factor shared by these two countries is a strong institutional framework, with full legal backing, to guide the detailed functioning of the respective sector and its role in the wider economy. However, the institutional arrangements are very different between the two countries, in each case tailored to specific circumstances and even to the nature of the raw material concerned. This emphasises that a one-size-fits-all approach to the governance issue is not just unnecessary but may also be counter-productive. Having said that, there is much that can be learned and transferred from these case studies to other national contexts.

Main findings and conclusions

Recent trends in the use of export restrictions (Chapter 1)

Use of export restrictions is often highly unpredictable. Substantive international disciplines in this area are weaker than for import restrictions.

Export restrictions on raw materials have become more frequent over the last decade. The phenomenon includes bursts of escalating but relatively short-lived interventions (e.g. the spiral of restrictions triggered by rising global food prices in 2008-9) as well as creeping protectionism (certain minerals and metal scrap). Some restrictions have been in place unchanged for decades. Sometimes governments adjust restrictions several times a year. Governments use a variety of measures. The OECD Inventory records more than thirteen different types of export-restraining measures or policies, the most common of which are export permits, export taxes and quantitative restrictions.

Export restrictions are broadly applied across all raw materials sectors, from minerals and metals, and metal scrap, to wood and agricultural commodities. They are used mostly, but not exclusively, by emerging and developing countries and for a variety of reasons.

12 – OVERVIEW

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

Global markets for raw materials often feature a high concentration of supply of, and hence dependency on, production and exports by a small number of countries. When markets are dominated by a few exporting countries that supply many importing countries, export restrictions have a large and more extensive effect on trade.

Experience shows that export controls can trigger similar actions in other supplier countries, driving up prices further, making price volatility worse, and creating a crisis of confidence that spreads from one resource to the next. Nobody benefits. Countries using export restrictions for some minerals are often heavily reliant on imports of other minerals, where they may face a restricted supply due to the use of similar trade instruments by other countries. These and other circumstances make a strong case in favour of addressing export restrictions and their effects through coordinated action.

The OECD Inventory confirms a transparency deficit in the design and implementation of export restrictions.

Expected economic effects of export restrictions (Chapter 2)

Governments expect export restrictions to help achieve certain policy objectives and tend to ignore that restrictions invariably hurt trading partners and interfere in the allocation of resources in the domestic economy, entailing costs.

Export restrictions distort trade flows. When a country applies a restriction, the welfare of its trading partners invariably suffers. Importers pay a higher price on imports from the restricting partner, user industries see their costs increase and consumers may see the price for final goods rise.

In theory, when an export restriction is applied by a ‘large’ country on its raw material, domestic processing firms, as well as competing foreign raw materials producers, will be favoured at the expense of domestic mining firms and foreign processing firms. In this way, there is a “profit-shifting” effect of export restrictions.

Abroad, raw materials producers gain from higher world prices and lower exports of the firm(s) in the country that is subject to a tax or quota and will therefore increase production. Higher world market prices for their goods increase their profits. They may increase their investment, although due to the uncertainty of the policy, they will engage in less investment than they normally would if they were responding to sustainable changes in market conditions rather than a policy that may be altered. This is another way by which global welfare falls due to export restricting policies.

The welfare gains which a “large” country may hope to obtain from an export tax or quantitative restrictions will not materialise if partner countries caught by this beggar-thy-neighbour policy retaliate in kind. The “large” country is then also worse off.

Exports restrictions taken by one economy give trading partners an incentive to divert their imports to other non-restricting countries supplying the same commodity. Diverting demand to other non-restricting countries creates pressure there to export more. When the restricting country is a large supplier and hence its action lowers world supply and raises world price, this can significantly increase the price of the commodity in the global marketplace. This may prompt these countries to restrict their exports in turn, the result of which would be a further rise in the price on the world market.

Export restrictions reduce domestic prices in the countries applying the measures. They indirectly subsidise domestic industries that use the restricted commodity as input. Assisting downstream industries to grow and compete may be the intended result of such restrictions. However, the restrictions punish producers of the commodity and discourage investment that will ensure long-term local supply of the raw material.

OVERVIEW – 13

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

Real-world observations on the effects of export restrictions (Chapters 3 and 4)

Steel, and the iron ore, steel scrap and coke used for steelmaking are part of a supply chain with many industrial activities as end users. Together, these commodities also represent an important share of countries’ industrial production, in the case of emerging economies more than 10%, and significant shares of industrial value added, but their trade is hampered by many export restrictions.

Diversion of raw materials to domestic downstream industries is an important effect of export restrictions, which motivates the policy choices in many countries using those measures. The wisdom of using restrictions to those ends is put into question by the results from a multi-country, multi-sector Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model. The simulation measures the effects of a simultaneous removal of export taxes in steel and steelmaking raw materials markets, including the indirect effects of the restrictions through the supply chain. When regions that apply export taxes remove these in coordination with similar action by trading partners, their downstream industries actually benefit.

Supply chains are increasingly global, relying on imported intermediate inputs and exporting finished products or semi-finished products for further processing. This means that removing a trade distortion) at one step of the chain has consequences throughout the global economy. As demonstrated for the steel industry, the CGE model simulation of a removal of all export taxes increases global supply and decreases world price. Through these effects and resulting changes in the pattern of increased imports and exports production costs for steel and the main inputs for steelmaking fall across all regions.

Partly because other countries join in the removal of export taxes, production costs decline for the steel industries of all regions that remove restrictions. The same effects are found for the scrap, iron ore and coke industries. The regions with the highest export tax levels experience the greatest price changes, leading to increased demand for their products and higher levels of production that contribute to GDP growth. Overall, coordinated action to lower and eventually remove export taxes helps both the upstream and the downstream industries expand, including in the countries that remove their export taxes.

In another sector, agriculture, use of export restrictions increased noticeably during the 2007 to 2011 period, when the world economy was hit by the financial crisis and the price of many agricultural commodities were rising and volatile. The presence of multiple causal factors makes it difficult however to isolate the effect of export restrictions alone.

Use of a set of statistical approaches found some evidence that the restrictions lowered agriculture exports from the countries imposing them. However, this was not always the case. On a year to year basis, because of the type of measure or its short duration, annual exports from some countries using restrictions continued flowing. In other cases, as would be expected, exports from countries using restrictions were substantially reduced relative to their level in the previous year; but whether due exclusively to the restriction or to tight domestic markets (which might have motivated the restriction itself) is not always clear.

Often the measures taken were highly restrictive (e.g. export bans) and subject to frequent changes, which causes uncertainty, a condition conducive to market disruptions caused by panic buying, shortages and oscillating monthly prices.

Market disruptions occurred in certain markets such as rice or wheat especially during 2008 and 2010, when many restrictions were applied. Some mitigating factors prevented further deterioration. Most restrictions were put in place for only a short time, there was sufficient global supply in order to meet demand and other suppliers stepped in. In most years from 2007 through 2011, exports from countries without restrictive measures made up for potential shortfalls, which allowed global exports to expand despite export restrictions of some countries. However, it cannot be ruled out that individual importers had difficulties finding alternative suppliers, which caused uncertainty and higher costs for them.

14 – OVERVIEW

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

Approaches for better control, and more transparent use, of export restrictions (Chapters 5 and 6)

Efforts to enhance disciplines on export restrictions at the multilateral level have stalled, but there has been progress in negotiating restraints on use of export restrictions through bilateral and regional trade agreements.

The provisions found in some RTAs have the potential to inform future rulemaking in this area at the multilateral or pluri-lateral level. Other RTAs extend the disciplines already agreed in WTO rules. Existing disciplines in WTO on export restrictions are however less precise and more open to interpretation than disciplines in other areas, e.g. import restrictions.

RTAs set controls in different, often innovative ways. Many RTAs circumscribe use of export restrictions by setting specific conditions for their use, e.g. by prescribing maximum time limits for their use, or specifying situations in which the restrictions are not allowed or the types of products that can be restricted. Some fix ceilings for export taxes. Other RTAs grandfather restrictions that are in place but do not allow new ones.

RTAs recognise the importance of transparent and predictable application of permitted measures, often requiring members to observe higher publication and consultation standards than are found in WTO provisions. For example, an approach common to many RTAs is to set specific conditions on use of export restrictions. These RTAs showcase various ways of controlling export restrictions, without necessarily banning their use altogether.

Transparency regarding the use of export restrictions should be improved, given the inadequacy of many information policies at national level and the variation in transparency practices across countries.

Transparency is an important policy objective in its own right. Transparency allows trading partners and market operators to anticipate interventions in trade and adjust. Global markets work best when traders and end users can base decisions on rational assessments of potential costs, risks and market opportunities.

Transparency does not mean de-regulation. It is about a predictable business climate for all. Neither exporting nor importing countries benefit from opaque, unpredictable conditions of trade. Non-transparent export regulation in restrictions-using countries deters investors and stifles growth of the export sector in these countries. In countries applying export restrictions, non-transparency can encourage corruption and make it more difficult for a government to ensure regulatory compliance.

Transparency norms in WTO, RTAs and general guidelines for good governance together form a set of state-of-art principles and information requirements that governments can use when they develop and implement export restrictions. The resulting list (provided in Chapter 6) is also a benchmark against which governments can determine the adequacy of their own and their trading partners’ present information policies and which can guide improvements that governments may wish to pursue on their own or through collaboration.

Alternatives to use of export restrictions (Chapter 7)

Export restrictions are undertaken for different reasons, ranging from the generation of government revenue to the conservation of resources, environmental protection and industrial diversification away from resource extraction into upstream or downstream activities. Some may be justified and compatible with WTO rules while others not.

With respect to raw materials, the specific issues that export restrictions are expected to address, in those countries that use them, are in the main domestic market or policy failures, unrelated to trade. Previous chapters in this volume show that the effectiveness of export

OVERVIEW – 15

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

restrictions in achieving any of the policy objectives requires close scrutiny. Trade measures such as export taxes or quotas will not be first-best policy instruments for dealing with these issues. Some countries which have the same policy objectives have addressed these effectively without resorting to export restrictions.

Economies dependent on mineral export have to manage the risk of export volatility resulting from booms and busts of international commodity markets. For public sector revenues and spending such dependence is a source of uncertainty and instability. In the case of Chile, the government receives a substantial share of its revenue from the mining sector, but notwithstanding fluctuations in revenue due to changes in copper prices and hence profits of mining firms, does not link government spending to the commodity cycle. Revenue is managed by applying a structural balance rule that disciplines government spending leading to budget surpluses in times of high revenue intake, typical of commodity booms, and provides stable sources of revenue during periods of low government income. Fiscal surpluses have been invested in sovereign wealth funds. A strong legal framework with checks and balances, and accounting practices open to public scrutiny, contribute to its success.

Industry development and diversification is possible in the absence of export restrictions. Chile has developed mining-related sectors, although the largest share of exports comes from mining and mineral extraction is primarily an export-related activity. A widely shared view holds that the country has no comparative advantage in downstream processing. Rather, by opting for promoting a range of less capital and less energy intensive intermediate goods and services industries that support mining operations, Chile is following a path which other minerals-rich countries, including Australia, Canada, Finland and the United States, have taken. These countries are all successful exporters of goods and services in the field of mining technology.

Looking forward

Just as collaboration at the multilateral level proved to be the most effective vehicle for putting in place today’s disciplines on import-restricting trade instruments, a multi-country approach would also be the most effective way to make lasting progress on disciplining export restrictions. There are international discussion and decision-making institutions for this purpose, including the various WTO fora, regional country groupings and trade negotiating fora, the G20 process, as well as smaller sectoral initiatives, such as the global Agriculture Market Information System (AMIS).

These existing mechanisms as well as possibly new multilateral collaborative fora dedicated to raw materials can contribute to address export restrictions and perhaps other trade policy issues in the raw materials sector comprehensively and decisively, leading to results that far exceed the sum of uncoordinated initiatives by individual governments. This volume attempts to contribute to such efforts, highlighting that export restrictions invariably reduce global welfare, typically fail to achieve their stated objectives, and that alternative policy approaches can be more effective at home while avoiding negative international spill-overs.

Notes

1. OECD Workshop on Raw Materials, Paris, 30 October 2009, and OECD Workshop of on Regulatory Transparency in Trade in Raw Materials, 11-12 May 2012.

2. OECD (2010),The Economic Impact of Export Restrictions on Raw Materials, OECD Trade Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264096448-en.

Reference

OECD (2014), Inventory of Restrictions on Exports of Raw Materials. http://www.oecd.org/tad/ntm/name,227284,en.htm.

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 17

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

Chapter 1

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE

Barbara Fliess, Christine Arriola and Peter Liapis1

1.1. Introduction

For decades, trade policy negotiations have concentrated on reducing import barriers that governments use to impede access to national markets and protect domestic producers. The focus has widened in recent years, with governments and the private sector also paying much closer attention to policies and practices that hinder their access to raw material supplies from exporting countries.

Industrial raw materials prices on world markets remained fairly stable during the 1980s and 1990s; since the early 2000s, however, world markets came under pressure from strong economic growth in major emerging and developing economies. Prices of many raw materials soared to historic levels from 2005, and although the adverse environment of the financial crisis abruptly reversed the trend in 2008-09, countries engaged in extracting and exporting minerals have become more inclined to regulate output and trade. Many of these resources are critical inputs for industrial production and have to be procured by many countries through trade. A similar situation has developed in markets for agricultural products. Global demand for agricultural goods has been growing as a result of increasing world population, and higher world incomes have resulted in greater demand for more diversified, healthier diets. Strong demand and periodic weather-related production shortfalls have resulted in higher prices. When the prices of wheat, rice and other agricultural commodities reached record highs during 2007-2009, several governments concerned about inflation and the internal food security situation took steps to restrict export flows.

Access to raw materials, including imported materials, determines in a sense the “heartbeat” of an economy. Traditional industries producing motor vehicles, machinery or steel are major consumers of basic and other minerals as inputs. Since the 1990s a range of new technologies has created additional demand for many industrial raw materials, often used in very small quantities although not visible to end-consumers. A smartphone, for example, contains from 9 to 50 different metals. An array of different minerals are used in areas of clean energy technology. Besides iron ore, ferrous scrap and various alloying metals for steel structures, wind turbines contain aluminium, cobalt, copper, zinc and certain rare earth metals. Building a hybrid car requires aluminium, cadmium, cobalt and at least 16 other metals. The number of non-renewable materials used to make a solar panel, or a LED light bulb, is even higher. Economic activity depends on raw materials, many of which are traded around the world because no country has domestic endowments of all the inputs needed. Thus, all economies are to some extent vulnerable to changing conditions in some raw material markets.

The prospect of more restrictive export policies has prompted firms to factor the risk of less secure world market access to raw materials into their business strategies. Governments of countries that are reliant on procuring food and industrial raw materials abroad have also been following developments on global markets more closely. Where they are dependent on access to commodities that are produced abroad but are of strategic industrial and military value to their own economies, they have begun developing strategies for mitigating supply risks and reducing supply-chain vulnerabilities caused by reliance on foreign supplies.

2 The issue of export restrictions and the

distortions they create in the global marketplace for raw materials and the products for which they

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 18

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

are inputs has been raised in many trade policy discussions. The rise of tensions and outright conflicts underlines the importance of achieving a more restrained and orderly use of these measures.

This chapter describes and analyses the spread of export restrictions in international trade in raw materials. It draws on recent OECD survey data on export restrictions available from 2009 to 2012 for industrial raw materials and for agricultural raw materials from 2007 to 2011. Section 1.2 outlines the development and the salient features of the global demand-supply relationships and trade in raw materials. Section 1.3 presents statistics compiled by the OECD on the incidence of measures that restrict raw materials exports, starting at the level of broadly defined product groups and trade relationships between countries and then examining in more detail the types of measures adopted and products affected. Section 1.4 looks at the situation of selected industrial and agricultural product groups, namely steelmaking raw materials, mineral waste and scrap, non-ferrous metals, rice and wheat. Section 1.5 examines the motives that prompt governments to introduce export restrictions and identifies features of the measures and ways in which they are implemented from which the distorting effects on international trade can be gauged. Section 1.6 concludes.

1.2. Why the heightened concern about raw materials supplies in recent years?

Demand for industrial and agricultural raw materials has grown consistently over the past 100 years in line with production. The pattern of supply and demand itself has also changed over time. For decades, developing countries were increasing and diversifying their production of raw materials, while demand for them – especially for industrial raw materials – was driven primarily by industrial growth in developed economies. Since the early 2000s, however, accelerating economic growth in China, India and other emerging economies has increased global demand for raw materials, which has contributed to a significant expansion of international trade. China provides the most striking example of recent changes taking place in some of these countries with expanding industries. In 1955, China was the leading producer of 14 commodities monitored by World Minerals Statistics, and by 2012 had become the leading producer of 44 commodities and a top-three producer of a further 12 commodities. Notwithstanding this, and despite a growing and diversifying mining sector, China’s rapidly growing industries have not been able to meet all their mineral needs from domestic supplies and have sourced some of their requirements in the international market (British Geological Survey, 2014).

Increasing incomes, changes in tastes, growing expectations to be able to consume seasonal products throughout the year, rising population and improved communication, transportation and logistics have all led to a steady expansion over time of global trade in agricultural goods. Between 2000 and 2012, trade in agricultural and food products grew at an annual average rate of 10% from less than USD 311 billion to just under USD 1 trillion.

3 As most of

the population and income increases are taking place in the developing world, trade patterns have evolved accordingly. In agriculture, high income countries supplied 58% of the world’s agricultural exports in 2000, but by 2012 their share had fallen to less than 45% reflecting the additional output emanating from developing countries. Even more dramatic is the drop in their share of agricultural imports falling from about two-thirds of the world’s total to about 40% during this time. Developing and emerging countries are not only trading more with the developed world, they are also trading more with each other. South-South agricultural trade was only 14% of the total in 2000 as against a hugely increased 29% in 2012.

Figure 1.1 tracks the evolution of global export volumes for the major categories of non-

energy commodities over the past decade. The increase in global minerals and metals requirements

and production has led to sustained growth in world exports that was reversed only temporarily by the onset of the world financial crisis of 2008. Exports of minerals and metals have doubled since the early 2000s, reaching a record high of 2.3 billion metric tons in 2013. Exports of agricultural commodities rose by 74%, to 1 billion tons. Traded metal waste and scrap more than doubled between 2000 and 2013 from some 48 million to 104 million tons, which is a rough estimate

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 19

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

because UN Comtrade statistics in this sector are poor for many countries. Wood exports, on the other hand, declined by 30% during the same time period.

Figure 1.1. Global exports raw materials, by sector (net weight)

Note: Net weight of gross exports of unprocessed and semi-processed minerals, metals and wood products and all WTO-defined agricultural products. For the list of products that comprise each category in the figure see the methodological notes accompanying the OECD Inventory accessible at: http://qdd.oecd.org/subject.aspx?subject=8F4CFFA0-3A25-43F2-A778-E8FEE81D89E2. Global exports refer to all countries of the world. Data excludes intra-EU trade.

Source: UN Comtrade.

Every country imports at least some of the raw material inputs necessary for industrial production. While dependence on access to foreign sources varies across economies and industries, exporting and importing economies alike have faced a situation of rising and also more volatile commodity prices in the last decade. Sometimes prices have skyrocketed in the course of a few months. For example, the price of rare earth metals as a whole doubled from 2010 to 2011, while prices of some elements like lanthanum and cerium (both rare earths) rose by 900%. Prices of antimony and tungsten more than doubled over this same period (Silberglitt et al., 2013). Agricultural commodities have experienced similar volatility. Between 1975 and 2000, cereal prices were low and stable, but this situation changed within a few years. Food prices as revealed by the IMF’s food price index rose steeply between 2005 and 2008 to the highest levels in 30 years, before falling by 33% in the second half of 2008. Another peak in world food prices was reached in 2011.

4

World market prices of individual agricultural commodities showed even more extreme swings, and remain much more volatile than in the first five years of this century (see Chapter 4, section 4.4 for more details).

Thus, as demand for raw materials has increased, global markets have become tighter, prices have risen, and so has the tendency for countries supplying these markets to tax exports or erect export barriers in various ways. Export restrictions have become part of the problem of escalating prices and volatile markets for raw materials. They have caused growing apprehension among countries, both developed and developing, that depend on imports for foodstuffs and other raw materials.

Several factors render concerns about restrictive export policies more acute. The first is that resource endowments, and consequently production of raw materials, have a very uneven geographical distribution. This is especially true for minerals and other industrial raw materials. For example, while nickel is mined in at least 30 countries, zinc in 40 countries, and silver in more than 50 countries, global supply of other minerals is concentrated in a small number of countries. In

Agriculture

Minerals and metals

Waste and scrap

Wood

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Million metric tons

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 20

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

2012, China alone produced 91% of the world’s supply of rare earth metals on which products ranging from hybrid electric vehicles and energy-efficient light bulbs to cell phones and computer displays depend. Some 60% of the world’s chromium, used mostly by the chemical and metallurgical industries, was produced in South Africa and Kazakhstan, which together account for 99% of all currently known chromite reserves. Almost 90% of world production of platinum and related metals occurs in South Africa and the Russian Federation. Recent world production shares of leading producers are shown in Table 1.1 for a number of raw materials. The production figures for minerals and metals mask the fact that known reserves are often less concentrated. The prospect of new supply coming into the market can act as a buffer when demand exceeds supply and prices rise. However, even when high prices lead to new investments, it takes years for mining operations to start.

In contrast to minerals, agricultural commodities are renewable resources. All countries produce agricultural products, but some countries do not produce enough foodstuffs to feed their own populations and thus need to import them. Although world supply of agricultural commodities does not have the pronounced oligopolistic features of many markets for industrial raw materials, there are some large players here too (Table 1.1). Droughts or government interventions affecting supply in key producing regions can easily disrupt global commodity markets and upset trade relationships.

Another factor heightening concern about restrictive export policies is that, in the short run, there are few or no substitutes available for many of the necessary inputs. For example, rare earth metals, antimony, and tungsten are difficult to replace without significantly increasing production costs or compromising the performance of the products in which they are used. Rare earths are used to make lasers and many components of electronic devices and defence systems, antimony is crucial for flame retardant plastics and textiles, and tungsten is used to produce cemented carbides for cutting tools used in many industries (Silberglitt et al., 2013). To safeguard against possible supply shortfalls, some industries and governments have stepped up efforts to stockpile industrial commodities essential for their operations (see, for example, Areddy, 2011, p.10). Similarly, the food price spike of 2008 has given impetus to initiatives at national and regional levels to hold more food stocks in reserve.

In the case of manufactured goods, attempts are being made to reduce dependence on access to primary raw materials by recycling more secondary material (waste and scrap) so that it can be used in the making of new products. Steel, copper and aluminium are among the most recycled secondary materials today, which have become globally traded commodities. As prices for primary raw materials have risen, collecting and processing scrap for re-use has become increasingly cost-effective and small-scale secondary markets and trade opportunities are emerging even for metals used in minute quantities that are difficult to recover, such as rare earths. Another incentive for recovering scrap for recycling is that this process can be very efficient in saving water and energy, and is otherwise environmentally sound.

The availability of secondary material for recycling depends on past production and is limited at national level. With demand growing, and in order to prevent shortages in certain geographical areas and surpluses in others, it is crucial to be able to trade metal scrap internationally as freely as possible. However, the global market for metal waste and scrap has also seen a steady increase in recent years in government-imposed export bans and other types of export restrictions.

The increased use of export restrictions across raw materials markets has caused concern and friction, including two recent challenges at the WTO to the legality of export restraints imposed by China on a broad set of raw materials.

5 At the same time, there have been efforts to strengthen

the disciplines on export restrictions of the multilateral trading system. While WTO rules on the use of import restrictions are numerous and extensive, those on export restrictions are more limited. These multilateral rules are described in Annex 1.A. Various proposals for improvement have been tabled during the ongoing Doha Round trade negotiations, but concrete steps in this direction could not be agreed. As Chapter 5 of this volume shows, the bulk of concrete recent achievements in restraining the use of these measures has occurred in the context of negotiated regional trade agreements (RTAs).

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 21

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

Table 1.1. Production for selected raw materials

Product Major producers, by share of

world production (2012)

Top 5 producers’

share

Figures in parentheses are percentage shares %

Minerals and metals

Antimony China (82), Tajikistan (4), Russia (4), Bolivia (3), South Africa (2) 95

Chromium South Africa (44), Kazakhstan (20), India (12), Turkey (9), Oman (2) 87

Cobalt Democratic Republic of Congo (68), China (5), Zambia (4), Australia (4), Cuba (3)

84

Copper Chile (32), China (10), Peru (8), United States (7), Australia (5) 62

Iron ore China (44), Australia (18), Brazil (13), India (5), Russia (4) 84

Lithium Chile (49), Australia (30), Argentina (9), United States (5), China (4) 97

Nickel Philippines (17), Russia (14), Indonesia (13), Australia (13), Canada (11)

68

Platinum group metals South Africa (59), Russia (27), Canada (5), United States (4), Zimbabwe (4)

99

Rare earth oxides China (91), United States (4), Australia (3), Russia (2) Brazil (0.2), Malaysia (0.1)

100

Tin China (40), Indonesia (31), Peru (9), Bolivia (7), Brazil (4) 91

Tungsten China (83), Russia (6), Canada (3), Bolivia (2), Rwanda (1) 95

Wood products

Coniferous industrial roundwood

United States (23), Canada (13), Russia (10), China (7%), Brazil (4) 54

Non-coniferous tropical industrial roundwood

Indonesia (28), Brazil (14), Malaysia (10), India (9), Thailand (5) 66

Agricultural commodities

Maize United States (32), China (24), Brazil (9), European Union (7), Argentina (3)

74

Palm oil Indonesia (51), Malaysia (35), Thailand (4), Colombia (2), Nigeria (2) 93

Rice (milled) China (30), India (22), Indonesia (8) Bangladesh (7), Viet Nam (6) 73

Soya beans United States (31), Brazil (31), Argentina (18), China (5), India (4) 89

Soya oil China (27), United States (21), Brazil (16), Argentina (1), European Union (5)

84

Wheat European Union (20), China (18), India (14), United States (9), Russia (6)

68

Note: Figures for shares are rounded up. Production figures for minerals and metals are for ores and concentrates or, where applicable, further processed materials.

Source: Production figures - Minerals and metals: British Geographical Survey (2014). Tropical industrial roundwood: ITTO (2012). Coniferous industrial roundwood: FAO (2014). Agricultural statistics from the US Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agriculture Service, Production, Supply and Distribution, on line http://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/psdQuery.aspx.

Export restrictions stand out in the conduct of trade policy not only because the WTO disciplines regulating their use are less developed, but also because of the opaque way they are used by governments, which makes it difficult to follow and predict what governments are doing or planning to do. Accurate, timely and accessible information about policy measures is a necessary condition for predicting supply and managing production risk. Opacity itself can be a formidable

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 22

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

barrier to trade. Because the use of market-distorting export restrictions is less systematically notified to trading partners through the WTO system, making these policies more transparent is a challenge in its own right.

To contribute to greater transparency, the OECD began collecting detailed information on export restrictions in the raw materials sector in 2009 (see the following section). Promoting more transparent use of these measures at national government level is another area where the OECD has been actively working. Some of the results of that work are presented in Chapter 6 of this volume.

1.3. Profiling the presence and spread of export restrictions

In the past, comprehensive and up-to-date information on export restrictions has not been readily available. The WTO maintains databases of notifications that members must make when they use some types of export restraints, but these notification obligations are insufficiently enforced. Some industry associations have begun to monitor export restrictions for their members, but this is usually done for the specific sectors in which they operate. Some governments include export restrictions in their regular exercises of monitoring trade policies abroad that are of interest to their countries.

In order to fill this information gap, the OECD started collecting information on export restrictions in 2009, systematically surveying a large set of countries and raw materials. The analysis in this chapter draws on this unique database. The OECD Inventory of Restrictions on Trade in Raw Materials (OECD, 2014a) (hereafter called the OECD Inventory) covers both industrial raw materials and primary agricultural and food commodities

6. The structure of each of the

two parts of the Inventory is tailored to the type of information it contains and its availability. For industrial materials, the Inventory records restrictive trade measures for more than 80 industrial raw materials in their primary and semi-refined/processed state, and in waste and scrap form.

7 For this

information, the survey aims to cover 84 countries (considering the EU as a single region) and data for the entire period 2009 to 2012 are currently available for 72 countries. The survey covers around 80% of world production volume of minerals, metals and wood in their primary state and a large share of related global trade (67% of 2012 total value of exports of primary materials, 45% of total exports of primary and semi-processed materials combined, and over 90% of exports of metals waste and scrap). For agricultural products, 16 countries are surveyed for export restrictions covering the whole range of agricultural commodities as defined by WTO. The most complete set of data for agricultural products covers the years 2007 to 2011, although for some countries available data extend outside this period. The list of surveyed countries and products is provided in Annexes 1.C and 1.D.

Since many more countries were surveyed for industrial raw materials than for agricultural products, the analysis presented in this chapter uses the former part of the Inventory more extensively, complemented by selective information about export restrictions from one sector of agriculture, namely primary bulk commodities.

8

Overview

The list of measures surveyed by the OECD Inventory is comprehensive, ranging from export taxes, prohibitions and non-automatic licensing requirements, to price and tax measures (Box 1.1). These measures are known to restrain export activity. They typically increase the relative price of exported products, decrease the quantity of exports supplied or change the terms of competition among suppliers. The different types of measures are explained further in Annex 1.B. The Inventory does not report export restrictions that are expressly sanctioned by international agreements in well-defined circumstances.

9

The OECD Inventory documents widespread use of export restrictions for industrial raw materials in recent years. Some of the measures recorded as being in force in 2012 (at HS6 level) have been in place for many years or even decades, but three quarters of them have been

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 23

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

introduced since 2007. More than half the measures in effect in 2012 were introduced after 2009 and almost a quarter in 2012. Expressed as simple counts of measures recorded at the HS6 product level, 466 of over 2000 measures recorded as being in effect in 2012 were introduced in that year (Figure 1.2).

Box 1.1. Types of measures surveyed and recorded by the Inventory

Export tax Dual pricing scheme

Export surtax VAT tax reduction/withdrawal

Fiscal tax on exports Restriction on customs clearance point for exports

Export quota Qualified exporters list

Export prohibition Domestic market obligation

Export licensing requirement Captive mining

Minimum export price/price reference for exports Other measures

Figure 1.2. Year of introduction of measures present in 2012

Note: Measures are counted at the HS6 level of product classification. The measures are restrictions on industrial raw materials. Restrictions that expired and then were reintroduced in the following year were counted as a new introduction of a measure.

Source: UN Comtrade.

Of the 72 countries with data available for 2009-2012, 12 countries did not apply restrictions in 2012 for any of the surveyed products. The other 60 countries applied at least one restriction between 2009 and 2012. OECD Inventory entries exist for nearly all the 90 minerals, metals and wood products at the HS6 product level covered by the survey (see Annex 1.C) and this large number of products affected by restrictions has not changed since 2009.

The agriculture and food section of the OECD Inventory covers numerous products, many of which were subject to export restrictions at least once during 2007 to 2011. Grouping these products into four general categories

10, horticultural products were the least affected by export

restrictive measures, while semi-processed products were restricted the most often. Over this five-year period, among the 16 countries whose agricultural trade data are recorded in the Inventory, there was a 58% probability that an individual country would impose an export restriction on at least one bulk product in any given year, relative to a 50% probability for semi-processed products.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

Number of measures

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 24

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

However, there were nearly twice as many individual restrictions in place on export of semi-processed products (532 restrictions at HS6 level) relative to those of bulk products (278 restrictions at HS6 level). The measures applied covered the whole gamut of instruments listed in Box 1.1, with outright bans the most common (used by 13 of the 16 countries in the database), followed by export taxes (9 countries) and export quotas (9 countries). At times, countries used a combination of these measures, either concurrently or sequentially.

Certain trends and patterns regarding the use of export restrictions and products affected can be seen:

Export restrictions are broadly applied across all raw materials sectors, from minerals and

metals, and metal scrap, to wood and agricultural commodities. The majority of restrictions are

applied by emerging and developing countries.

The period between 2009 and 2012 witnessed the introduction or tightening of over 900 measures at the HS6 product level in the industrial raw material sector. By comparison, only 400 measures in the Inventory were eliminated or relaxed during that period, and many of these resulted from the liberalisation commitments of countries such as Tajikistan, Ukraine and Viet Nam under their WTO accession protocols. As for primary agricultural bulk commodities, some 337 new or tighter measures (at HS6 level or higher) were added during 2007-2011, and some 70 measures were removed or liberalised.

Many export restrictions imposed between 2007 and 2011 on agricultural commodities were temporary, sometimes lasting less than a year. For industrial raw materials, on the other hand, interventions tend to be medium- to long-term. It was rare that a measure in force in 2009 was discontinued in the course of the next three years.

Governments use a variety of measures. A summary of the number of measures recorded in the OECD Inventory for 2012 is provided in Table 2. Non-automatic export licensing requirements and export taxes are particularly widespread across all three categories of industrial raw materials – minerals and metals, metal waste and scrap, and wood. Governments also impose quantitative restrictions (prohibitions and quotas), notably on exported waste and scrap and primary bulk agricultural commodities, or resort to other policies that restrain export flows.

While a detailed description of international trade patterns is beyond the scope here, it is useful to provide information on the size of the trade flows corresponding to the four categories of raw materials, the leading importers and exporters, and amount of trade affected by the export restrictions in the OECD Inventory. Worldwide imports of the more than 80 minerals and metals surveyed for the Inventory amounted to USD 1.2 trillion in 2012. OCED members, led by the EU and the United States, accounted for 44% of these imports. Moreover, 65% of the imports into the OECD area were sourced from other OECD member countries.

11

Seven per cent12

of the 2012 total gross trade value of minerals and metals were subject to

export restrictions in 28 countries with available trade data. While at this high level of product aggregation the incidence seems quite small, a more nuanced picture emerges for individual products within the minerals and metals sector.

Metals account for the lion’s share of exports value in this sector, with a large share of exports subject to restriction at the individual product level. They comprise 43 products and were exported to the value of USD 1 trillion in 2012. Metal products include aluminum, copper and other base metals widely used across industrial applications, but also the so-called technology metals that are critical inputs to many high-technology industries. More than a third of the exports of metals like thorium (63%), the metal group niobium, tantalum, vanadium (54%), tungsten (52%), and magnesium (46%) were subject to some form of export restrictions in 2012.

13

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 25

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

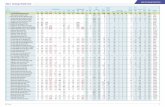

Table 1.2. Incidence of export restrictions by type of measure and sector

Minerals and metals

Metal waste and scrap

Wood Primary bulk agricultural

commodities

2012 2012 2012 2011

Domestic market obligation 5

Export prohibition 3 129 9 25

Export quota 20 9 2 7

Export tax 144 141 6 9

Licensing requirement 172 226 27 -

Other export measures 27 47 9 3

Total 371 552 53 44

Note: Counts of measures are at the HS6 level of product classification. For the categories minerals and metals, metal waste and scrap, and wood: Since many products comprise more than one HS6 line and the number of lines per product varies, the simple count was adjusted by dividing counts at the product level by the number of HS lines constituting each product. This adjustment removes the bias inherent in simple counts of HS6 product lines. ‘Other export measures’ include such items as restrictions on customs clearance points for exports, qualified exporters lists, the setting of minimum export price/price references and captive mining. For primary bulk agricultural commodities: the counts of measures shown are not adjusted. Argentina collects export duties of 5% on agricultural products. The OECD Inventory records only exceptions or changes to this policy. Only licenses related to export quotas are recorded for agriculture products.

Source: OECD Inventory, as of June 2014.

The impact of export restrictions is larger and more extensive when they are imposed on products whose world market are dominated by a few exporting countries trading with many

importing countries. For example, the top 5 exporting countries account for 92% of the USD 1.9

billion magnesium export supply in 2012. China alone produced 85% of this metal14

and accounted for about two-thirds of the value of magnesium exports whereas the shares of nine of the top ten importers ranged between 1% and 8%. South Africa, Rwanda, and Brazil made up three-quarters of total exports for the metal group niobium, tantalum and vanadium, which was mainly imported by China (38%), the EU (33%), and Thailand (14%). In instances where the source of trade is concentrated, like magnesium, the impact of export restrictions employed by one exporter is distributed across a larger number of importing countries.

The remaining items in the industrial raw materials section of the OECD Inventory are 41 mostly non-energy industrial minerals. While at USD 183 billion they account for a minor share of the total trade in minerals and metals, some minerals are vital for every economy around the globe. Potash and phosphate rock materials, for example, are used in fertilizers, which are critical inputs for food production. According to US Geological Survey data

15, Canada and the Russian Federation

together account for the bulk of world potash production but significant amounts are also produced in other countries, including Belarus and China, both of which have restricted exports in recent times. In 2012, 18% of potash exports were subject to restrictions by these two countries. For phosphates, the figure of restricted trade (of China and Malaysia) is 5%.

Potash is a highly concentrated export market, where the top 5 exporters (Canada, Russian

Federation, Belarus, United States and Jordan) account for almost all the trade (92%). Over 111 countries are recorded as having imported potash in 2012. For some countries, particularly those with a large agricultural sector, it is a significant part of their raw mineral imports. For example, potash represents 24% of Brazil’s 2012 mineral and metal imports.

World imports of wood products in the OECD Inventory totalled USD 56 billion in 2012. Led by the United States and Japan, OECD imports accounted for 51% of world imports. The largest importers were China (26%), Japan (15%), United States (12%), and the EU (11%), and the top 10 importers accounted for 80% of world imports. Heading the list of suppliers were Canada (14%), the EU (13%), the Russian Federation (12%), the United States (11%), and China (11%). Exports are heavily restricted. Overall, 39% of the value of world exports of wood products surveyed for the OECD Inventory were subject to export restrictions in at least 11 countries, by countries that were

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 26

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

for the most part leading producers and exporters in this sector. Exports of non-coniferous tropical plywood are both highly restricted and concentrated. The top two producing countries, Malaysia and Indonesia, applied export measures in 2012. Malaysia alone accounted for almost half (49%) of the total trade value and Indonesia over a third (37%). In contrast, the top 5 exporters of non-coniferous tropical sawnwood make up only 65% of world trade and only one of the top 5 exporters applied any restrictions. In the case of non-coniferous tropical plywood, the export policies have a larger effect, since a total of 111 countries import the product from a highly concentrated and highly restricted market.

At some USD 84 billion in 2012, global trade in metal scrap and waste materials is just a fraction of trade in primary minerals and metals extracted from the ground. The largest importer of scrap was China (27%), then European Union (14%), Turkey and South Korea (11% each), and the United States and India (each 9%). The top 5 exporters were all OECD countries, led by the United States (24%), the EU (22%), Japan (7%), Canada (6%) and Australia (2%). The OECD Inventory reports that in 2012 restrictive policies targeting one or more scrap or waste items were in place in 39 (mostly developing) countries. Some 7% of exports of metals waste and scrap totalling USD 5.8 million (according to UN Comtrade) were affected in 2012.

In fact, only a third of the products classified under waste and scrap were found in the UN Comtrade database. Aluminium, copper, platinum and steel are items where trade flows are reported more consistently across countries. For these items, the share of 2012 exports affected by the measures in the OECD Inventory ranged from 3 to 8%. In this sector, approximately 64% of trade was intra-OECD, and OECD countries sourced almost 80% of their imports from other members, a much higher share than their imports of primary minerals and metals. But with production of scrap being concentrated in OECD countries and twelve developing countries imposing bans on exports of waste and scrap, these trade patterns are not surprising.

Total agriculture imports, as defined by the WTO, were valued at USD 914 billion in 2011, of which primary bulk commodities were 27%. Top importers of bulk commodities were China (18%). followed by EU (16%), Japan (7%), United States (6%) and Mexico (4%). Overall, non-OECD countries accounted for half of the imports. The non-OECD countries supplied about half of total exports as well. The leading exporters were the United States (25%), Brazil (15%), Argentina (7%), Canada and India (6% each). The 15 countries for which at least one export restriction was recorded during the 2007-2011 period are all non-OECD countries.

Among the bulk agricultural commodities, wheat, barley and rye were the subject of export measures in the Russian Federation, Argentina and Ukraine in 2011 (the latest year of available OECD Inventory data on export restrictions for agriculture). These countries were also among the top ten exporters of these primary products and accounted for 20% of the total trade. Of the three commodities mentioned, barley had the largest share of exports sourced from these countries with export restrictions (34%), while only 19% of wheat and rye exports came from these sources. Rice was also restricted in 2011, by Argentina, China, Egypt and Myanmar, which accounted for 4% of total exports.

As is shown in the following sections, the situation occurring in 2011 and 2012 represents a point on a trend in export policy that already became apparent much earlier. Many restrictions were already in place in 2009. Especially in the minerals and metals sector, measures have been seldom discontinued, and many individual products have seen the number of export restrictions in force grow between 2009 and 2012.

What measures do governments use?

1. Non-automatic export licensing requirements

At the HS6 product level, non-automatic export licensing requirements are the measure most frequently reported by the OECD Inventory for minerals and metals. Exporters must obtain prior approval, in the form of a license or permit, to export the product. By reviewing applications for a licence on a case-by-case basis, governments can control who exports and how much. The process

1. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE USE OF EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE – 27

EXPORT RESTRICTIONS IN RAW MATERIALS TRADE: FACTS, FALLACIES AND BETTER PRACTICES © OECD 2014

of applying for a license generates extra transaction costs for exporting firms, in time and sometimes monetary terms. Moreover, when processing times are long or unpredictable, this hinders the ability of firms to react quickly to sales opportunities in foreign countries.

In 2009, these measures were applied by 25 countries, including 8 countries that were among the top 5 world producers for at least one of the products affected. The number of countries was slightly higher in 2012 (26) and included more leading producers (9). They affected the trade of some 240 different primary and semi-refined or processed minerals and metals products, at the HS6 level of product classification. Table 1.3 lists the products most frequently subject to non-automatic licensing requirements in 2012, along with the countries imposing them. China, the Dominican Republic, Malaysia, the Philippines and the Russian Federation figure prominently as countries where for many or even all of the products shown businesses must obtain a license to sell abroad. Apparently countries apply export licensing requirements to many products simultaneously or sequentially, rather than targeting particular products selectively.

Table 1.3. Minerals and metals most frequently subject to export licensing requirements, 2012

Product HS6 lines, adjusted