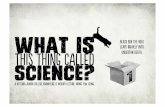

This Thing Called Forensic Accounting

Transcript of This Thing Called Forensic Accounting

26 A R I Z O N A AT T O R N E Y J U LY / A U G U S T 2 0 0 7

ComputerCONTENTSBeing Proactive With Electronic Discovery

BY CRAIG REINMUTH………………….... 28

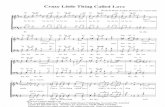

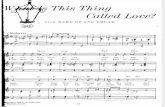

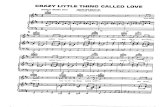

This Thing Called Forensic Accounting

BY KATHLEEN BARNEY…………………. 34

SPECIAL FOCUS:

27J U LY / A U G U S T 2 0 0 7 A R I Z O N A AT T O R N E Y

r ForensicsIf there were one brief definition of the work that forensic accountants do, it maybe this: looking beyond the numbers and seeing situations as they really are.

Grasping the truth of the matter is vital to lawyers as they weigh and value theircases. More so than ever before, that truth can be obscured by the sheer complexityof new technologies. But despite that—or perhaps because of it—courts demandmore and more in the way of transparency and disclosure, in discovery and beyond.

This month, we feature two articles that address the issues that many lawyers dealwith daily. Called forensic accounting or computer forensics, this is an area thatrequires skill and an attorney’s full attention.

Forensic accounting is once again front-page news due to such frauds as Enron andWorldCom. It seems you cannot turn onCNN without hearing about another exec-utive brought up on fraud charges.Forensic accountants’ previous claim tofame was the capture and prosecution of AlCapone for tax evasion. Despite the presscoverage over the last few years, many peo-ple are unaware of forensic accountants,nor do they have an understanding of whatthese people do.

When forensic accountants hear theinevitable question “What does you do?”they know a paragraph explanation willensue. The questioner’s initial expectationis excitement at what must be cloak-and-dagger work: “Oh, like CSI” or perhapsastonishment: “You count dead people’smoney.”

It’s our sorry lot to have to disappointthese individuals. That’s right: Forensicaccounting is not exactly like CSI. In fact,forensic accountants do not sit in a darkroom with a small flashlight examiningfinancial documents. And they don’t go tothe crime scene and count the money in thelatest victim’s wallet before the coroner

hauls away the body.Forensic accounting is a specialized field

carved out of multiple disciplines. Auditingtechniques, accounting skills and investiga-tive procedures are all key components ofthe practice. The Association of CertifiedFraud Examiners (ACFE) defines forensicaccounting as the application of accountingskills to provide quantitative financial infor-mation about matters before the courts.

The ACFE distinguishes fraud examina-tion from forensic accounting but overlapsthe disciplines in fraud investigations. Thefield of fraud examination encompassesmany subsets, such as prevention, deter-rence, anti-fraud training, investigation,internal control assessments and fraud losscalculations. This differs from forensicaccounting because not all findings will beused in court.

Like any expertise, there are specialistsand generalists. Forensic accountants mayspecialize in financial or partnership dis-putes, construction or environmentalclaims, trust/estate valuations, damagescalculations or fraud investigations.

Most attorneys who retain a forensicaccountant are looking for an expert to

confirm or resolveallegations offraud. In order toassist attorneyswith cases involv-ing alleged fraud,a detailed fraudinvestigation mustbe conducted.

The major components of fraud investiga-tions include securing documentation relat-ed to the allegations, interviewing witness-es and suspects, seizing electronic informa-tion, analyzing financial statements andaccounts, and reviewing accountingprocesses and procedures.

It is important to note the differencebetween forensic accounting and financialaudits. The biggest misconception is thatfinancial audits will uncover all frauds. Anaudit is designed to detect material finan-cial statement fraud. But it is ill equippedto recognize many types of internal frauds,such as fictitious vendors or ghost employ-ees. The purpose of an audit is to verifythat the financial statements are true andfairly presented. The purpose of forensicexamination, on the other hand, is toreview possible exploitations of the internalcontrols over a company’s assets. In otherwords, forensic exams determine where theloopholes are and who is taking advantageof them.

The Need for Forensic Accountants

Is there really a need for forensic account-ing? Is fraud so pervasive that it affectscompanies of all sizes?

Unfortunately, yes. The ACFE con-ducts a study every two years regardingfraud in the United States. In the 2006Report to the Nation, the ACFE estimatedthat five percent of a company’s revenue is

w w w. m y a z b a r. o r g34 A R I Z O N A AT T O R N E Y J U LY / A U G U S T 2 0 0 7

BY KATHLEEN BARNEY, CFE

This Thing Called Forensic Accounting

Kathleen Barney, CFE, is a Senior Associate with the ForensicAccountant & Investigative Services Division of Eide Bailly LLP. She spe-cializes in financial fraud investigations and fraud prevention. She hasexperience in reconciling financial statements to determine occurrence oftheft and the amount of loss due to fraud. She is a Certified FraudExaminer (CFE) and the Treasurer of the Arizona Chapter of CFEs.

Computer Forensics

lost to fraud annually. When applied to thenation’s gross domestic product, the fraudloss equates to $652 billion annually.

Who is the hardest hit by fraud? Sadly,it’s the groups that can least affordit—small businesses. The medianloss per fraud instance in smallbusiness is $190,000, according tothe ACFE study. Fraud affects allbusinesses. The question is to whatextent is it affecting your clients.

How can attorneys use forensicaccountants to their benefit? As inall cases, it’s critical to have anexpert on your side. The CertifiedFraud Examiner designation is themost well known of the fraud cre-dentials for forensic accountants.Forensic accountants can becomeexperts in cases such as embezzlement,partnership disputes, marital dissolutions,insurance claims, securities fraud and bank-ruptcy.

Although forensic accountants are greatassets as expert witnesses, they can also bea resource to your firm as a consultant.Take the case of a business dispute.

Your client, a partner, wishes to bebought out of the partnership. A businessvaluation is conducted and the value of thebusiness is less than expected. Perhaps notall sales are being recorded on the books,

negatively affecting the value of the com-pany. A forensic accountant can beretained to investigate the possibility ofunrecorded or underreported sales. If the

forensic accountant determines the manag-ing partner is skimming $100,000 a year,then the revenue figure used in the valua-tion is grossly understated.

A second example is a child supporthearing in which the wife is looking toincrease the support and the husband isrefuting the wife’s need for additionalincome. The husband’s argument is thatshe moonlights as an exotic dancer andmakes more money then he does.Considering her job is cash intensive andnot conducive to a paper trail, how do you

determine her earnings? A forensicaccountant can conduct an analysis of herfinances. By using the net worth or expen-diture method, a forensic accountant could

indirectly sub-stantiate herincome.

Finally, acompany mayknow who isstealing andhow, but thepolice won’ttouch the casebecause of theirlack of resourcesfor financialcrimes. Yourclient looks to

you for civil remedies. Forensic account-ants can document the case and quantifythe total amount of loss the company hassuffered. The forensic accountants canthen issue their findings through writtenreports and/or oral presentations.Accountants’ attention to detail will bereflected in the report documenting thefraud. The forensic accountants can laterbe called to testify to their findings incourt.

Rule of thumb: If your client’s caseinvolves money, you should use a forensicaccountant.

Five Common MistakesAs in any other legal case, there are manyways a fraud investigation could be jeop-ardized. Some mistakes are made by theinvestigators or attorneys, but the majorityof mistakes result from the actions of thebusiness owner or executive.

Mistake 1: Mishandling EvidenceIt is imperative that when fraud is discov-ered, the evidence related to the fraud issecured. If an employee has altered invoic-es as a means to embezzle from the com-pany, those invoices must be collected,copied and the originals secured. The doc-uments are the evidence of the case thatlinks the suspect to the crime. If documen-tation is left in full access to other employ-ees, the argument could be made that the

w w w. m y a z b a r. o r g36 A R I Z O N A AT T O R N E Y J U LY / A U G U S T 2 0 0 7

Characteristics of a GoodForensic Accountant

• Solid foundation of accounting knowledge• Strong oral and written communication skills• Detail oriented• Effectively apply investigative techniques• Past investigative experience• CFE designation• Satisfaction of past clients• Independence

It is imperative that when fraud

is discovered, the evidence

related to the fraud is secured.

Computer Forensics

documentation was altered after it left thepossession of the suspect. If this was a mur-der case, you would not leave the suspect’sgun in the open where other people couldtouch it and add fingerprints to it.

Mistake 2: Altering OriginalsCopy, copy, copy. As attorneys, you areaware that you should always work from acopy and not the original, but do yourclients know that? On more occasions thenI can recall, clients have marked up andmade notes on original documentation.Some notes are as blatant as writing “for-gery” across a check. When making notesregarding documentation, it is best to usecopies or post-it notes. If someone writeson the originals, it is more difficult todetermine which employee altered thedocument.

Mistake 3: Lack of PredicationPredication is a necessary component of afraud examination. Predication is a set ofcircumstances that would lead a reasonableand professionally trained person to believea fraud has occurred, is occurring, or willoccur. This must be present before theinvestigation. Predication could be a tipfrom an employee, unreasonable answersor missing documentation. Without predi-cation, the investigation could be viewedas a witch hunt.

Mistake 4: Accusing or Altering the SuspectYour client finds out an employee has beenstealing from the company. The initialthought of your client may be to confrontthe employee. Unfortunately, this wouldbe the wrong action to take. There is a rea-son investigators interview the suspect dur-

ing the last phaseof the investiga-tion. If they inter-view the suspect inthe early stages,they lose the ele-ment of surprise,and the suspect isnow aware of theinvestigation.

One of threethings can happen.

The suspect denies the allegation and isnow aware the company is investigatinghim or her. Moreover, the suspect now hasthe opportunity to destroy evidence orcease other frauds he or she might havebeen perpetrating before detection.Second, the suspect may be innocent andthe company cannot prove the crime. Thiscould result in either a lawsuit broughtagainst the company by the accused or, atthe very least, a lack of trust and goodwillby the accused toward the company. In thebest-case scenario, the suspect admits tothe crime and leaves the premises withoutincident. This is a one-in-three chance thatyour client should not risk.

Mistake 5: Failure To Obtain aWritten StatementIf your clients ignore the warning inMistake 4 and confront the individual, thisnext problem usually occurs: The suspectadmits to committing the fraud, is termi-nated and is escorted off the property. Yet,no written statement is obtained from thesuspect. Now the supposed confession is a“he said/she said” argument. The suspect,aware of the ongoing investigation, usuallythen obtains legal representation andrefuses future interviews with forensicaccountants.

Protecting YourOwn Practice

Attorneys see cases from their clientsinvolving fraud often, yet they are unawareof how easily fraud can be perpetratedagainst them. Law offices fall victim tofraud every day. Due to the nature of theindustry, attorneys are always focused ontheir clients’ issues and not on those with-

in their own firm. Firms need to put checksand balances in place to protect the firm’sassets.

A local attorney once told me that threeout of five of the law firms he wasemployed by had an office manager orother personnel steal from the firm. Let’sface it: Lawyers are great at arguments, butnot usually as savvy with accounting.Attorneys fall into the same pitfalls as doc-tors; they need to hire people to handle thebilling and payments. Attorneys arefocused on their discipline and trust otherswill be responsible with their job duties.

Recognizing the signs of fraud is simpleif you know the fraud triangle. All threefactors of the triangle must be present for afraud to occur. The signs are pressure,opportunity and rationalization.

First, an employee feels the pressure ofa financial burden such as divorce, a gam-bling problem, alcoholism or an excessivelifestyle. This becomes his or her motiva-tion to steal. Second, opportunity exists inthe loopholes of the internal controls,which allow the employee to exploit his orher position for personal gain. Finally, thefraudster must be able to rationalize thebehavior. I have never met a perpetrator offraud who considered himself a crook. Themost common rationalizations are “I willpay it back,” “The firm can afford it” and“I’m not hurting anyone.”

The easiest way to mitigate fraud is bylimiting the opportunity employees haveto take advantage of their positions. If theopportunity for your employees to commitfraud is limited, then your employees willbe less inclined to attempt fraudulent acts.Keep in mind: Internal controls are inplace to keep honest people honest.

w w w. m y a z b a r. o r g38 A R I Z O N A AT T O R N E Y J U LY / A U G U S T 2 0 0 7

FRAUDTRIANGLE

Pressure Opportunity

Rationalization

AZAT

Attorneys see cases from their clients

involving fraud often, yet they are

unaware of how easily fraud can be

perpetrated against them. Law offices

fall victim to fraud every day.

Computer Forensics