Thinking as Form.pdf

Transcript of Thinking as Form.pdf

-

8/12/2019 Thinking as Form.pdf

1/3

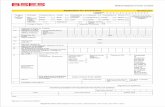

'Thinking as Form: The Drawings of Joseph Beuys'. Philadelphia and ChicagoReview by: Charles W. HaxthausenThe Burlington Magazine, Vol. 136, No. 1090 (Jan., 1994), pp. 53-54Published by: The Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd.Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/885724.

Accessed: 01/04/2014 03:20

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at.http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

The Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd.is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to The Burlington Magazine.

http://www.jstor.org

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=bmplhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/885724?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/885724?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=bmpl -

8/12/2019 Thinking as Form.pdf

2/3

EXHIBITION REVIEWS

. .. ,?joko00eat

..............................too, tyTu56. Adorationof theMagi, byJohannBoeckhorst. 1652.181.6 by 249 cm.(Bob JonesUniversity,Greenville; exh.Museum of FineArts, Boston).

cabinet paintings. Here also there is highquality, as in the great Banquetpiece by Jande Heem (no. 111) which is, for its degreeof finish and detail, extraordinarily large.It is such a good and representative paint-ing that one may well wonder why asmany as five more paintings by him wereselected for this show. There seems to besome redundancy here. The same mayapply to Frans Snyders, who is certainlymore varied than de Heem in style andsubject matter, but his emphatic presencewith seven paintings (including some incollaboration) probably does him toomuch honour. On the other hand, painterssuch as Jan Fyt and Pieter Boel, arguablywith the same aesthetic and historical sig-nificance, feature with one painting only.Altogether, The Ageof Rubensoffers us abroad overview of Flemish painting in theseventeenth century. The great mastersare adequately represented, and the showgives a good idea of what was achieved byFlemish painters in the various genres. Thisis not to say that the extraordinary phenom-enon of the flowering of the arts in theSouthern Netherlands in the seventeenthcentury is really expounded in its full com-plexity, but this is hardly an objective thatcould have been realised in one exhibition.Some aspects or artists may have beensomewhat overemphasised, and othersunderplayed (fbr history painting somequite important names are missing, andthe second half of the century as well asthe artistic scene in cities other than Ant-werp has been somewhat neglected). It ishoped that this exhibition will succeed inits aim to instil in the American public anappreciation for this rich tradition.Some notes on individual works follow:No.2: The collaborator of Hendrik de Clerk is not

Jan Brueghel but Denys van Alsloot.No.10: An extra argument fbr the suggestion thatthe composition was enlarged afterwards is theSnyders drawing of an eagle (British Museum, re-produced); it is however a ricordorather than a'study' as its left edge corresponds with the seamin the canvas.

No.12: The name 'Subter' which figures in the 1635Buckingham inventory is most likely a faulty tran-scription, in the final draft, of the name 'Snider',as he figures elsewhere in this document.

No.14: The lingering doubt whether the animalsshould be attributed to Snyders or to Paul de Voscan now be dispelled: a recent cleaning of theOrpheus n the Prado (no.1844), in which the ani-mals are very similar and have traditionally beenattributed to de Vos, has revealed Frans Snyders'ssignature (as well as that of Van Thulden for thefigure).Nos.15a and b: The proposed dating 1620-22 is un-convincing: the 1630s would be preferable.No.16: Certainly not a portrait of Nicolaes Rockoxand to be dated earlier, c. 1610-11.No.17: The landscape is rather by Jan Brueghel theyounger.No.48: French school?

No.61: The attribution to Jean de Reyn finds somecorroboration in the fact that a very similar head(looking out of the painting and thus possibly aself-portrait) occurs in his Adorationof the Magi inBergues (signed and dated 1641: see La peintureflamande au tempsde Rubens, exh.cat., Lille-Calais-Arras [1977], no.46).

No.90: The church in the background seems indeed(as stated in the catalogue) to be that ofAlsemberg.Since the spire of that church burned down on23rd June 1653 (not to be rebuilt before the nine-teenth century) this may be suggested as a terminusante quem. ARNOUT BALIS

NationaalCentrumoor ePlastischeKunstenvan de 16de en de 17de Eeuw, Antwerp*The Age of Rubens, by Peter C. Sutton, with thecollaboration of Marjorie E. Wieseman and DavidFreedberg, Jeffrey M. Muller, Lawrence W. Nichols,Konrad Renger, Hans Vlieghe, Christopher White,Anne T. Woollett. 630 pp. incl. numerous ills. in col.and b. & w. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in associ-ation with Ludion Press, Ghent). ISBN 0-8109-1935-4(HB); 0-87846-404-2 (PB).

Philadelphia and Chicago'Thinking as Form: The Drawings ofJoseph Beuys'Drawing might seem a narrow, conven-tional focus for the first major Beuys exhi-bition the United States has seen in fourteen

years. Beuys, after all, tirelessly preachedan 'expanded concept of art'; he sought todemocratise artistic activity by redefiningit as any and all manifestations of humancreativity. Yet the nearly 200 works in theretrospective Thinkingas Form: The Draw-ings of Joseph Beuys (closes PhiladelphiaMuseum of Art, 2nd January; then at

the Art Institute of Chicago, 19thFebruary to 24th April) demonstrate thatwhat Beuys termed 'drawing' exemplifiedthis expanded concept as much as did hisobjects and actions. Ultimately, 'drawing'for him was not a matter of medium butof dimensions: in the Beuysian lexicon,drawing was any physical sign of mentalactivity that was preserved and presentedin a two-dimensional format. The categoryencompassed not only traditional drawingmedia but also oil paint, felt, blood, grease,pressed plants, and other unconventionalsubstances; not merely iconic representationbut writing, typing, stamping, staining,affixing. And what he initially practisedas a private, intimate medium of artisticexploration became one of public perform-ance.A traditional kind ofdrawing dominatedthe long period of relative artistic isolationin which Beuys worked from the end ofthe Second World War until the early1960s. These early sheets are typicallyfigurative representations, mostly women,animals, landscapes- images in which wesee Beuys's mental world taking shape.Those from the late 40s and early 50s tendto be rendered in faint, delicate graphitelines; in the early 50s he also began towork increasingly with liquid media. Manyof these drawings can seem almost artless,and yet they possess a strange beauty (aquality to which Beuys claimed indiffer-ence). Certain renderings of animals andof women evoke Palaeolithic art; others, ontorn, stained fragments of paper, suggestarchaeological finds, remnants of somevanished culture in which drawings hadnot yet become 'art'. This effect was notaccidental: Beuys, against the grain ofmodernism, was fond of speaking of hisdrawings as a materialised form of thought;their value lay in their function as signs,not as expressions of feeling or as auton-omous, aesthetically pleasing configurationsof indeterminate ideational content. Ofall modern artists, Leonardo came closestto his ideal - not Leonardo the painter,but Leonardo the thinker, who left count-less traces of his thinking in graphic form.In the works executed in liquid media,the primary thought embodied in thedrawings seems to have been about processmore than about the motif, which in manyinstances becomes nearly indecipherable.In Untilled(Salamander) (Fig.57) executedin Beize (apparently a ferric chloride sol-ution) and hare's blood, Beuys managedto preserve a sense of the original liquidstate of the medium - indeed the figureshave a waxen quality reminiscent of certainof his early sculptures. And the processthrough which the fluid media assume afixed, stable form itself exemplifies Beuys'sidea of sculpture the moulding of fluidmatter into solid form. Woman, becauseof the nature of her reproductive function,was closely identified with Beuys's concep-tion of sculpture; the sculptural processreproduces the life process, from conceptionto decay. The incorporation of blood as amedium underlines that analogy.This 'sculptural' concept of drawingmust have stimulated Beuys to developthe medium he called Braunkreuz,a thick

53

This content downloaded from 182.185.224.57 on Tue, 1 Apr 2014 03:20:08 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/12/2019 Thinking as Form.pdf

3/3

EXHIBITION REVIEWS

57. UntitledSalamander), byJoseph Beuys. 1958.Hare'sblood,Beizeand pencilon cardboard,29.5 by 21 cm. (Klusercollection, Munich;exh. Art Instituteof Chicago).reddish brown pigment that he began usingaround 1960 (in her catalogue essay, AnnTemkin is particularly illuminating on theoverdetermined connotations of this term).'Like fat and felt in his sculptures, Braun-kreuz unctions as primal matter; employedmonochromatically, it emphasises paint asplastic substance rather than as hue; in itsmateriality it dramatises drawing as for-mation rather than as delineation.In its colour and, occasionally, in itsconsistency, Braunkreuzhas fecal associ-ations that, besides evoking a process oforganic transformation, seem especiallyapt for someone who once characterisedhis objects as the 'waste products' of hisactivities.2 Significantly, the introduction

of Braunkreuzalso coincides with a newcategory of drawing for Beuys: from thenon, many 'drawings' are not iconic repre-sentations at all but lists, notes, calendarpages, the detritus of Beuys's manifoldactivities, marked or partially overlaid withthis trademark substance (Fig.58). Here,the addition of Braunkreuzeems to signifythat these ephemera, these hasty scrawlsindicating a mind at work, are also art. Tothis same end Beuys often used a Braunkreuz-coloured ink stamp.Beuys did not limit the application ofBraunkreuzmerely to his own products. Itbecame a means of appropriating the mostdiverse range of quotidian artefacts - texts,images, and objects from commerce,journalism, and advertising. The meresttrace of Braunkreuzerves to allegorise themwith Beuysian metaphors. One of the moststriking examples in the exhibition is apage from the Frankfurter llgemeine,eatur-ing an illustrated article on a Soviet mobilenuclear power-plant. By affixing one of hisown drawings, linking it to the news photoby means of a skein of Braunkreuz,andpainting a brown cross onto each, Beuysappropriates this curious object as a meta-phor of art as generator of spiritual energy.The exhibition is marked by a chrono-logical imbalance that is profoundly in-dicative of a change in Beuys's attitudetoward drawing: 135 objects cover thetwenty-two year period from 1948 to 1969,while only thirty-two date from the lastsixteen years of his career. In a 1969 inter-view, Beuys conceded that his interest inproducing objects was diminishing and thathis teaching was his greatest work of art.3It is at precisely this time that the functionof drawing changes. After 1970 conven-tional drawing usually functions as theservant of language, as schematic illustra-tions of a message conveyed in speech orwriting. This is evident in several smallersheets, but most dramatically in the largeblackboards that Beuys used in his lectures

(Fig.59). The ideas he had initially ex-plored through images and materials inthe remarkable drawings of the 40s or 50shere find a more precise articulation inlanguage, albeit a visually less absorbingone. Here drawing and performance, for-merly the discrete, private and publicspheres of Beuys's activity, are synthesised.Interestingly, as 'drawing' became moresemantically focused for Beuys, his latersculptures, such as The endof the twentiethcenturyand FPlight, eem to have becomeless so, gaining at the same time a formalconcentration and suggestive power thatare no less effective for being more conven-tional.The catalogue, with extended essays byAnn Temkin and Bernice Rose, is a wel-come addition to the still sparse and quali-tatively spotty literature in English. Per-haps to avoid the distorting gloss of somany recent German publications on theartist, they have opted fobra matte finishthat unfortunately dulls some of the moredelicate works to the limits of legibility.But the texts are valuable and rich in in-sights. Temkins's two essays happily gobeyond Beuys's drawings to discuss his artand theory as a whole. With Caroline Tis-dall's indispensable catalogue of the 1979Guggenheim retrospective long out ofprint, this publication is now the best in-troduction to the artist available in English.CHARLES W. IIAXTIIAUSENWilliamsCollege,Williamstown

'Thinkings Form.TheDrawingsfJoseph euys. yAnn Temkin and BerniceRose, with a contributionbyDieterKoepplin. 78pp. + 62figs.and 172col.and b. & w. pls. (Thames& HudsonwithPhila-delphiaMuseumof Art/Museumf ModernArt,NewYork,1993), 29.95.ISBN -87633-089-8.2'InterviewwithWilloughbyharp',nEneryPlanfor the WesternMan:JosephBeuysn America.Writingsbyand nterviewsith heArtist, d. c. KUJONI,ewYork, 1990],p.85.Ibid.,.86.

58. To:'Manresa',yJoseph Beuys.1966.Oil(Braunkreuz)pencil,penandinkonpaper,29.5 by21 cm.(Privatecollection,Switzerland;exh. ArtInstitute ofChicago).

S59. Actionhirdway,byJosephBeuys.1978.One ofthreepanels, halkonslate,133by133cm.each).

54

(Helge'7 ' Achenbach,Duiisseldorf;exh.

58'

Art Institute of5' Chicago). 59.

54

This content downloaded from 182.185.224.57 on Tue, 1 Apr 2014 03:20:08 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp