Theories on the Great Depression

description

Transcript of Theories on the Great Depression

Theories on the Great Depression: Harris, Sklar and Carlo: Secular Stagnation, Disaccumulation, Monopolies-Overproduction and the Long Waves

Broadway @ 50th Street, NYCJune 22 1998

Bobst Library, NYU, NYCJune 24, 1998

Bobst Library, NYU, NYCJune 26 (fri), 1998

Seymour E. Harris, ed., Postwar Economic Problems. New York: McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p. 3, 3rd paragraph.

Martin J. Sklar, The United States as a Developing Country: Studies in U.S. History in the Progressive Era and the 1920s. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 149-170.

Antonio Carlo,'The Crisis of the State in the Thirties', Telos, no. 46, winter, 1980, p. 62 -80.

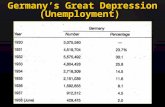

Introduction

The causes of the Great Depression have been difficult to determine. Moreover, broadbased financial data series which would be necessary to establish the definitive interpretation do not exist. What we are left with is a hodge-podge of theories, some specific, limited data and large amounts of anecdotal information. Almost all interpretations are heavily riven with the politics of the particular writer. Stalinist interpretations of the era preached about the 'final' collapse of capitalism, while another Soviet economist, Nicholai Kondratieff had only recently developed a theory which posited that Marx was incorrect and that no 'final' collapse of capitalism was likely. Kondratieff spent at least part of the depression decade in the Gulag, awaiting his fate. Free-marketeers such as Milton Friedman would have us believe that incorrect monetary policy either directly led to the Great Depression, or at the very least, greatly compounded the problem.

Various conspiracy theorists have equally various views on the Great Depression. Richard Hofstader did a collection of his articles in the 1950s, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, with a central article by roughly the same title which described many of these fringe theories, although not specifically related to the Great Depression. Still, as another serious economic problem looms across the Pacific, any serious writing about

today's problems needs to have a perspective on the causes of the Great Depression. This section uses views and information from these three writers:

1. Seymour E. Harris secular stagnation2. Martin J. Sklar disaccumulation3. Antonio Carlo monopolies and overproduction

Harris on Keynes and Secular Stagnation

A major book was published in 1943 as to what might be expected to happen to the American economy after the end of war. Contributors included prominent academic economists, and members both of the Roosevelt government and private industry.1 Articles by Seymour E. Harris, Alan Sweezy and Richard Bissell are discussed here. Much of the book was concerned with John Maynard Keynes' idea of 'secular stagnation', defined in Sweezy's section. The book was edited by Harris, a then major Keynesian economist from Harvard University. The book represented a broad perspective of mainstream views. Harris went out of his way to make two major points. First, the book was dedicated to preserving the private enterprise system, but within the limitations that income was to be distributed in such a way as to preserve 'the maintenance of demand'. Second, if the private system was unable to deliver sufficient demand, then government investment was the alternative. And the alternative to government investment under conditions of a new depression was the 'doom of capitalism'. 2 The problem during the Great Depression was too rapid increases in productivity versus employment and total wages:

The depression years witnessed a remarkable advance in output per man-hour; but our gains were more than nullified by the large rise in unemployment and the reduction of employment. 3

Nor was there any doubt by Harris as to the cause of the rapid increase in national income between 1940 and 1943, massive deficit spending by the federal government. The deficits basically elminated unemployment and actually brought people into the industrial economy who had not been there before the war. These deficits were being run during a wartime emergency, but Harris questioned why full employment and high standards of living could not be achieved during peacetime. While Harris might have been concerned with the postwar, an ancilliary question was why the federal government waited so long to institute the policies in the first place. Why not 1934 instead of 1942? 4 Again, although Harris may not have understood why productivity had so greatly exceeded consumption during the period before the Great Depression, he certainly understood that inordinant efficiency was the problem. Two other writers in Harris's book mentioned similar ideas, Alan Sweezy and Richard Bissell. Almost 25 year later, a left-wing political scientist/historian, Martin J. Sklar, would develop the theory of disaccumulation to more adequately describe how the shift in electrical energy use in the factory system had created the crisis.

Alan Sweezy's chapter in Harris's book on postwar America, described the Keynesian idea of secular stagnation. 5 Conventional business-cycle theory saw depressions as temporary problems, largely resolvable within the private sector. Keynesians saw the possibility that depression, i.e. secular stagnation, had become the norm in modern capitalism since 1929, where federal intervention was necessary to keep unemployment from dropping to catastrophic levels. Stagnation theorists viewed the Great Depression as largely the culmination of the huge capital investments during the 1800s, which had begun to decline after the beginnings of the 1900s. A "stagnant" economy was not necessarily a static or dead economy. The problem was not that private industry was not investing in the economy, but that not enough investment was being made to keep employment at high levels. Thus strong technological progress could exist side by side with weak employment levels:

The thirties provide a striking example of "stagnation" combined with highly dynamic economic and social development. Even in the best year of the decade the American economy failed by a wide margin to achieve full employment of available resources. Yet technological progress continued at a rapid pace , productivity rose markedly [see Spurgeon Bell, Productivity, Wages, and National Income, Washington, 1940, p. 270-280], and in the second half of the decade gross private investment averaged nearly $10 billion a year. The trouble again was not there was no investment, but that investment was not enough to keep income at a level that would fully use the country's tremendous productive resources.[see "Savings and Investment,"Hearings before the Temporay National Economic Committee, Part 9, p. 4122]. 6

While $10 billion might not seem like a great amount in today's economy, it must be recalled that the entire gross national product during many years of the 1930s was not over $100 billion and several years saw less. Thus in the later part of the 1930s, almost 10% of the GNP went into private investment. In some respects, the theory of secular stagnation could be seen as a refutation of Marx's crisis theory based upon the falling rate of profit. Keynes was saying that even during this major crisis, that certain parts of the capitalist system could maintain their profits through increasing labor efficiency, perhaps with a degree of monopoly control and a compliant central bank willing to keep monetary policy loose enough to keep a major part of the aggregate production moving into consumption. How long this balancing act by the major corporations could have continued is open to question. And at least some Keynesians, perhaps even Keynes

himself believed that secular stagnation had become the permanent state of capitalism after the crash of 1929.

Although Sweezy did not specifically mention the long wave model, he clearly understood that new sources for investment had been occurring during the 1800s. Stagnation theory coincides not with conventional business cycle theory, but more with long wave theory, in that it takes into account the large scale investments made during the 1800s- but without necessarily seeing the investments,7 as long waves of investment. The economy boomed during heavy investment stages and then began to shift into depression once investment slowed. Thus the capitalist economy of the 1800s became essentially addicted to periodic heavy investment. Within this model- a labor theory of value model- economic growth could occur some when combination of the following were increasing:

1. population involved in manufacturing production 2. investment in new manufacturing capacity, [i.e, new labor-based innovations] 3. territorial expansion

Obviously America during the 1800s was a special case of capitalist growth in that we had rapid population increases from European and Asian sources during most of the century, 8 heavy investments in steel to build the railroads in the middle 1800s and more investments in the 1890s and at least until the closing of the frontier around 1890- large scale territorial expansion. It would have been reasonable for America to have experienced rapid growth during the 1800s and it occurred. However by the early 1900s, all three bases of growth had decreased in importance. These changes probably would have sent the world economy into decline before 1920, had not World War l intervened. The war itself, as well as the postwar reconstruction needs of Europe materially aided America in keeping income high during the 1920s. 9

Stagnation theorists believed that the special conditions which had existed during the 1800s growth phase of capitalism, had decreased in importance to such an extent that continued private investment could no longer be counted upon to keep the economy moving forward. Moreover, while Sweezy could imagine future technical innovations requiring large scale capital expenditures as had the railroads, automobiles and electricity; he felt that no technical innovations were likely to create enough capital investment to overcome the relative decline in population and territorial growth in the early 1900s:

This is the basis on which the stagnation school predicts a long-run deficiency of investment opportunity. 10

If the deficiency [in investment] should persist over a long period of time, the economy would be secularly depressed or "stagnant". 11

Thus from the stagnation stand point, World War l had basically covered over the problem of all major capitalist powers- that of lack of perceived good investment opportunities at home and conflict over investment in what is now called the underdeveloped or Third World. 12

Again, stagnation theorists viewed the Great Depression as largely the culmination of the huge capital investment of the 1800s, which had begun to decline after the beginnings of the 1900s. From the stagnation model, it is difficult to see the same degree of cyclical or perhaps wave-like patterns of investment which long wave theory would suggest, but the absolute amounts of investment were tremendous during the 1800s, regardless of whether a theory suggests cyclical patterns or simply collapses the investment total into a single amount. World War l had slowed this investment decline and the rebuilding in aftermath had also hidden the long term trend to lower investment. The resolution of the Great Depression for stagnationists would not lie in conventional economics and private investment, for there few opportunities for profitable investment during the 1930s, in addition to the relative decline in territorial and population trends.

While in retrospect given the large increases in world population, it might seem a little odd to have claimed a loss of importance of population in the growth of the economy, at no time during the 1900s had so large a proportion of the population moved into manufacturing as had occurred during the 1800s, when large scale migrations to major national cities had occurred all over America and Europe. Such large proportional increases in the labor force probably did not again occur until the modernization program in the People's Republic of China during the 1980s. For the stagnationists, increased investment led to increased jobs and production, and both increases led to increased consumption- as production was recycled back into consumption completing the loop from investment to consumption. However without new sources of profitable investment for private capital, the stagnationists looked to the federal government to fed investment through deficit spending.

Richard Bissell's chapter could easily be read as critical of the secular stagnation thesis. The critical nature of the chapter may be inferred both by the actual content of Bissell's writing, as well as by the fact that it had originally been printed in Fortune magazine during 1942. Bissell noted that Keynesians believed that the Great Depression had marked a major break in American economic development:

Prior to that time [crash of 1929], they [the Keynesians] admit opportunties for private investment had, on average, been adequate to maintain reasonably full employment in a reasonably level of economic activity with, of course, frequent

depressions what could be explained by special or temporary circumstances. But 1929 marked the end of this era. Thereafter we might expect to suffer from a secular stagnation due to a chronic deficiency of investment opportunity as well as from the deep depressions associated with cyclical flunctuations. 13

Several factors were suggested by Keynesians for this dramatic shift:

1. Loss of the frontier, 2. Slowed population growth after 1929, 3. Technology changes towards 'capital-saving' machinery in the 1920s, 4. No new innovation like the automobile after 1929.[my emphasis] 14

Without attempting to cover Bissell's criticism of the Keynesian logic for the shift toward secular stagnation, it is interesting to note that the last two reasons listed from Keynesianism by Bissell fall into the type of model which I lean towards. Taken together factors 3 and 4, support the idea that technology had changed from introducing new labor-based innovations, (like the automobile), towards labor-shrinking innovations, possibly like that of electricity. Bissell in his criticism of the Keynesian view on technology, noted that investment in technology had not fallen during the 1930s. 15 What Bissell did not discuss was what the technological investments of the 1930s had bought the capitalist class, continued large-scale uneployment. And even Bissell felt compelled to end his chapter with the following:

Finally, if all efforts to promote private investment fail [in the postwar economy], very serious consideration should be given to the possibility of socializing a sufficient part of the economy so that the government could, without competing with private industry and without frittering away its funds on leaf raking, maintain through its own direct action a high rate of productive investment. 16

Sklar on Disaccumulation

Martin J. Sklar wrote an article for Radical America in 1969, where he emphasized the shift from the accumulation of capital to disaccumulation.17 The article was a harsh criticism of the economic ignorance of the then 1960s campus radical movement, a situation which has probably worsed since the article was published, with the ubiquitous

spread of the post-modern, diversity racket on campus. The article was included in a 1992 book on America as a developing society.18 Much of the article is weighed down with difficult Marxist nomenclature, but the core of article is a reference to the difference between earlier economic crises and the Great Depression, an idea which he described as the transition from capital accumulation to disaccumulation:

For example, in a society undergoing capital accumulation in the course of industrialization, the expansion of manufactured goods-production entails the expansion of the labor force in the production and operation of the means of production in manufacturing. At the point where there is no such increased employment of labor-power in the production and operation of the means of production, that is, where the production and operation of the means of production results in expanding production of goods without the expansion of such employment of labor-power, capital has entered the process of transformation to disaccumulation. In other words, disaccumulation means that the expansion of goods-production capacity proceeds as a function of the sustained decline of required, and possible, labor-time employment in goods-production [my emphasis]. 19

Put succintly, Sklar was saying that it is possible to begin to increase total production of goods in society, even as the total number of labor hours declines. Sklar implied that the means by which this process of disaccumulation had occured was directly related to the way in which energy, specifically electrical energy, began to replace previous methods of energy use in the manufacturing process, including in this case the early electrical processes in the factories. During the 1920s, electrical energy was being used to replace human labor in the factories, in a process similar to that described by Marx. The process began to accelerate during the late 1920s:

By implication, the period of the passage from the accumulation phase of capitalist industrialization of goods-production, to the disaccumulation phase, coincides with the partial and progressing extrication of human labor from the immediate goods-production process. This is as true of

agriculture as it is of industrial manufacturing...the mode of goods-production progressively undergoes reversion to a condition comparable to a gratuitous "force of nature": Energy, harnessed and directed through technically sophisticated machinery, produces goods, as trees produce fruit, without the involvement of, or need for, human labor-time in the immediate production process itself. Living labor-power in goods-production devolves upon the quantitatively declining role of watching, regulating, and superintending. 20

Although Sklar did not discuss the long waves, he placed the shift from accumulation to disaccumulation in the time span from about 1907-1929, the time span approximately associated with the third Kondratieff long wave. Sklar placed particular emphasis in the period of 1919-1929, the approximate period when the use of electricity was being revised from driving large, long whole factory belt-driven systems to factory-wide electrical grids powering small, point-of-production electrical motors. 21 These trends were as prevalent in agriculture as in manufacturing and there was a general tendency to:

...reduce the number of employees producing the same, or an increased quantity of production. 22

In one crucial difference with some other writers, Sklar held that 'net investment' in new plant and equipment had been declining since the 1890s.23 Sklar defined the collapse of 1929 as marking the transition from accumulation to disaccumulation. He believed that the Great Depression, World War ll and the following rebuilding phase, largely hid the process of that transition. Sklar believed that the problems associated with that transition began to reassert themselves partly during the 1950s, but more seriously during the 1960s. Sklar noted similarities between his concept of disaccumulation and Keynes' idea of secular stagnation. 24

Carlo and Monopolization

Antonio Carlo, writing in the early 1980s for a then left-wing academic journal Telos. Carlo discussed four theories about the collapse of 1929. He rejected the monetarist and coindental theories, and interesting he also rejected the classic Marxist interpretation of the 'falling rate of profit' hypothesis as the trigger for the Great Depression. Carlo accepted a combination of monopolization and the overproductionist model, also derivative from Marxist economics. 25 These ideas are somewhat different from Sklar and Harris. He concluded the article by noting that:

Capitalism can achieve almost full employment, but it can never permanently overcome its contradictions. 26

Carlo believed that the shift to monopolies during the early 1900s in major sectors of the world capitalist system had greatly exacerbated the normal, 'congenital' tendencies of capitalism towards over-production:

Signs of overproduction were everywhere [during the 1920s]. Yet, the decisive new fact was not overproduction, which is congenital to capitalism, but something else. Beginning with World War l, the tendency of capitalism to eliminate price competition and to control prices becomes crucial not only in the United States, but in the whole West...The problem in 1929 was monopoly domination, which had intensified capital's normal tendencies toward underconsumption. Thus, on one had, there were immense industial empires with an enormous capacity which could not be translated into an adequate increase of employment. On the other hand, increases in productivity do no result in corresponding reductions in prices, thus opening a serious gap between production and consumption.[my emphasis] 27

Sklar, Harris, Carlo and the Great Depression

Neither of the three writers mentioned here seems to have understood or accepted the long wave hypothesis as part of their interpretation, although Carlo's article did discuss the problem of Keynesian debt-finance of which I have written elsewhere. A long wave hypothesis helps to fill out the gaps. Previous long wave downturns had been resolved with new labor-based innovations. Thus Sklar's shift from accumulation to disaccumulation makes more sense, if it is believed that disaccumulation began in the 1920s- but largely as a result of two facts:

1. No major, new labor-based, long wave innovation was ready for the economy in the 1920s.2. By 1929, electricity was capable of increasing productivity, overproduction and correspondingly underemployment for several more years into the 1930s.

It was not simply that electricity had begun making labor redundant in the existing manufacturing sectors, but that no new labor-based innovation was ready for investment to absorb the increasing numbers of unemployed. Thus Carlo's overproduction-monopolization interpretation makes more sense for roughly the same reasons, as does Harris's views on excessive productivity.

Where the three writers may converge is over the issue of investment during the 1930s. Investment during the long waves was usually meant to increase total production. Eventually the investment decisions of the 1800s resulted in huge industrial monopolies in most advanced countries, as noted by Carlo and Paul Sweezy. And if there is a problem with stagnation theory's view on private investment during the 1930s, it is that it may have confused the decreased amount of investment with its direction. It was not simply that less investment was being made, but that much of the money was being spent upon increasing efficiency and decreasing the number of jobs in a stable or declining country-wide output.

Although not necessarily understood at the time of Sweezy's writing during the early 1940s, the 1920s shift in assembly line use of electricity had greatly exacerbated the entire long wave problem, making most existing capital stock even more productive than previously.28 And although not necessarily noted in the stagnation interpretation, the type of 1920s efficiency-related investment for the assembly lines, may have helped set the pattern for the 1930s as well. Thus not only was there no new profitable labor-based innovation to drive a new labor-based long wave, but private investment was then being driven to decrease even the currently existing labor forces around the globe.

During most of the capitalist era before 1929, profits had been derived out of an increasing level of total production. The long wave innovations had been profitable to the private investors, as well as having created a much higher standard of living for most industrial workers. Most investment decisions had been made in anticipation of increasing total output and realizing a profit from this increase. If the normal assumption behind private investment is the derivation of profit, once the stock market collapsed in 1929 private investment was bound to continue to try to derive profits. Unfortunately the changed circumstances indicated that investment was no longer necessarily oriented towards greater total production.

Investment during the Great Depression may have become more concerned with driving down labor costs and keeping a more constant or even declining output, than with further increasing inventory in an already saturated market. However as the profits for any company were kept up by such investment strategy, the overall effect was the loss of more aggregate buying power among the declining numbers of paid members ofthe working and middle classes. Productivity increases in the face of stagnant or declining aggregate country-wide production can only result in further job losses and a decrease in aggregate demand or country-wide buying power. 29 It was John Maynard Keynes who described this last problem most adequately at the time.

The bright forecasts in magazines like Wired may be highly over optimistic of how the new Internet revolution will turn out. It may well be that the stock market increases of the period from 1996 through summer 1998 had an empirical basis, in that greater individual company profits seemed more realizable under an Internet-driven system. Yet rapid profit increases must usually have a real basis in efficiency increases, driven finally towards massive overproduction and/or underconsumption. Ultimately, either must result in a mountain of inventory or huge levels of over capacity. Given the just-in-time model of most industrial sectors, huge inventories may not exist today, but world wide over capacity in both manufacturing and raw commodities is a fact seen in most daily accounts of the market. The problem today is whether or not the move towards the Internet represents a new phase of secular stagnation-disaccumulation. If this should prove true, then capitalism may well be facing its final crisis and the solution to that crisis will either sustain modern civilization or see it slowly erode in tribalism and petty wars.

______________________________________________________

1 Seymour E. Harris, ed., Postwar Economic Problems. New York: McGraw_Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p.xi, xii, 5. The contributors list included persons from Fortune Magazine, the Federal Reserve Board, theFederal Works Agency and a host of major academics from all over the country and the federalgovernment. The book was not written by a group of left propagandists. The editor made it clear that LordJohn Maynard Keynes was the primary influence upon the book. While it was possible that some of theassemblage had leanings further left, Marx was not even listed in the index, nor was commmunism or theSoviet Union. Back

2 Seymour E. Harris, ed., Postwar Economic Problems. New York: McGraw_Hill Company, Inc., 1943,p. 4, 5, 6. Back

3 Seymour E. Harris, ed., Postwar Economic Problems. New York: McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943,p. 3. Back

4 Seymour E. Harris, ed., Postwar Economic Problems. New York: McGraw_Hill Company, Inc., 1943,p. 3. Back

5 Alan Sweezy,'Secular Stagnation', in Seymour E. Harris, ed., Postwar Economic Problems. New York:McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p. 67. Back

6 Alan Sweezy,'Secular Stagnation', in Seymour E. Harris, ed., Postwar Economic Problems. New York: McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p. 69. Back

7 in cotton manufacturing in the early 1800s, in railroads and steel during the middle 1800s and inautomobiles, electricity, etc during the late 1800s and early 1900s, Back

8 The European and Asian immigration was largely voluntary, by immigrants seeking a better way of life inthe expanding American continent. The smaller African population in America had been the results largelyof force and their 'immigration' led to their enslavement primarily in the American South, until 1863 andthe end of the Civil War. Back

9 Alan Sweezy,'Secular Stagnation', in Seymour E. Harris, ed., Postwar Economic Problems. New York:McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p. 71-72 and p. 80. Back

10 Alan Sweezy,'Secular Stagnation', in Seymour E. Harris, ed., Postwar Economic Problems. New York:McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p. 72. Back

11 Alan Sweezy,'Secular Stagnation', in Seymour E. Harris, ed., Postwar Economic Problems. New York:McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p. 69. Back

12 From some left wing perspectives, it was this conflict over investment outlets between the capitalistnations of Europe which in fact led into both world wars. This was known as the theory of imperialism. Lenin believed that the key to promoting change in the capitalist core nations was to deprive them of their empires. Thus was born the Soviet Union, not long before the end of World War l. Back

13 Richard Bissell,'Postwar Private Investing and Public Spending', in Seymour E. Harris, ed., PostwarEconomic Problems. New York: McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p. 86. Back

14 Richard Bissell,'Postwar Private Investing and Public Spending', in Seymour E. Harris, ed., PostwarEconomic Problems. New York: McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p. 86. Back

15 Richard Bissell,'Postwar Private Investing and Public Spending', in Seymour E. Harris, ed., PostwarEconomic Problems. New York: McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p. 87. Back

16 Richard Bissell,'Postwar Private Investing and Public Spending', in Seymour E. Harris, ed., PostwarEconomic Problems. New York: McGraw-Hill Company, Inc., 1943, p. 110. Back

17 Martin J. Sklar,"On the Proletarian Revolution and the End of Political-Economic Society," RadicalAmerica, lll:3, May-June, 1969. Back

18 Martin J. Sklar, The United States as a Developing Country: Studies in U.S. History in the ProgressiveEra and the 1920s. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 149-170. Back

19 Martin J. Sklar, The United States as a Developing Country: Studies in U.S. History in the ProgressiveEra and the 1920s. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 155. Back

20 Martin J. Sklar, The United States as a Developing Country: Studies in U.S. History in the ProgressiveEra and the 1920s. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 155. Back

21 Martin J. Sklar, The United States as a Developing Country: Studies in U.S. History in the ProgressiveEra and the 1920s. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 159, 162, 163. In page 162 and 163, Sklar cited an congressional report which described many of these changes, which had startedduring the early 1900s, but which had accelerated during the 1920s. Recent Economic Changes in theUnited States, Report of the Committee on Recent Economic Changes, of the Presidents Conference onUnemployment, Herbert Hoover, Chairman, 2 vols., published for National Bureau of Economic ResearchNew York: McGraw-Hill, 1929. A number of pages in volume 1, including ix, x,xv, 87,88 and 91 were cited by Sklar.Back

22 Recent Economic Changes in the United States, Report of the Committee on Recent Economic Changes,of the Presidents Conference on Unemployment, Herbert Hoover, Chairman, vol. 1, published for NationalBureau of Economic Research, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1929, p. 471 and p. 880 (vol. 2), and p. 91, 92 in Martin J. Sklar, The United States as a Developing Country: Studies in U.S. History in the Progressive Era and the 1920s. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 164. Back

23 Martin J. Sklar, The United States as a Developing Country: Studies in U.S. History in the ProgressiveEra and the 1920s. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 167, 168. Other writers, perhaps Richard Bissell, have indicated that investment remained similar... Peter Temin in a 1974 book

showed the actual investment numbers from 1919 to 1939. While they show a decline during the 1930s,most years during the 1930s showed some investment. The 'net' investment during that period is however,something which I have not determined as of now. Whatever the 'net' investment, the crucial matter is intowhat type of technology the investment went. I contend that much of this 1930s investment was intented todecrease labor costs for a relatively stable of even declining level of production, as opposed to trying tocreate more total production. A partial support for this position may be obtained by simply looking at GNPnumbers for the 1930s. Peter Temin included those numbers in his 1974 book. Most years in the 1930s didnot see as great a GNP as in 1929, about $100 billion. I would contend that the investment in point-of-production electrical systems for assembly lines during the 1920s, not only showed how to greatly increaseproductivity during relatively booming economic times, but also how to increase productivity indeflationary or stagnating economic times.Back

24 Martin J. Sklar, The United States as a Developing Country: Studies in U.S. History in the ProgressiveEra and the 1920s. Cambridge, Mass.: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 160, 161.Back

25 Antonio Carlo,'The Crisis of the State in the Thirties', Telos, no. 46, winter, 1980, p. 62-63. In rejectingthe monetarist hypothesis, he cited R. A. Gordon, Economic Instability and Growth: The American Record.New York: Harper and Row, 1974, p, 45.Back

26 Antonio Carlo,'The Crisis of the State in the Thirties', Telos, no. 46, winter, 1980, p. 80.Back

27 Antonio Carlo,'The Crisis of the State in the Thirties', Telos, no. 46, winter, 1980, p. 64, 65.Back

28 This is again, an understanding from Martin J. Sklar with the term of "disaccumulation".Back

29 For a period of time this problem may be dealt with by exporting the surplus. However this methodcannot continue indefinitely, as monetary policies in the net importing countries will eventually workagainst the net exporting nations. Alternatively, the workers threatened with displacement in the netimporting nations, may demand rising tariff walls to protect domestic jobs. The current situation of Japan and America illustrates this problem.Back