The Value Growth Agenda

Transcript of The Value Growth Agenda

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

1/14

Number 13

The Value Growth Agenda

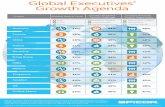

Setting the agendaFinding the right drivers of value growth

With so many options, which initiatives really matter?

By Ted Moser and Hanna Moukanas

As growth opportunities have become more dynamic and transitory,

the traditional pillars of strategy have been rendered obsolete.

Senior managers need a short, coherent list of initiatives to mobilizethe organization, tell outside stakeholders where the company

is headed, and reach the next profit zone before it shifts again.

5 Assembling the components of business design

11 Thought questions

Mercer Management Journal

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

2/14

Mercer Management Journal Setting the agenda 1

Compaq

- 63%

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

1997 1999 2001

Xerox

- 85%

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

1997 1999 2001

British Telecom

- 66%

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

1997 1999 2001

MV declinefrom peak

MV declinefrom peak

Procter & Gamble

- 46%

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

1997 1999 2001

MV declinefrom peak

MV declinefrom peak

$

billions

Note: Data is for April 1997 through April 2001. Source: Mercer Value Growth Database

By Ted Moser and Hanna Moukanas

Exhibit 1 Market value collapse

Finding the right drivers of value growthWith so many options, which initiatives really matter?

Every firm needs an effective value growth agenda, but not all firms have one. How else toexplain the extraordinary number of great firms with strong brands, fine products, and greatpeople that have struggled in recent years: Compaq, British Telecom, Procter & Gamble, and

Xerox, to name just a few (Exhibit 1)?

A high-impact value growth agenda is more than the initiative du jour. Its a prioritized short

list of actions designed to enable a firm to meet or exceed its own value growth targets and

the expectations of investors. It separates the essential must dos from the longer list of

should dos. The agenda often combines a mix of significant operational improvements with

focused fundamental change. It should be tirelessly communicated to all members of a com-

panys value growth coalition: customers, employees, suppliers, and investors. And since the

companys chosen profit zone is a moving target, the agenda needs to evolve over time.

But a value growth agenda only succeeds when it focuses on the right growth levers, at the

right time, and in the right sequence. And the company must execute it effectively. Take

Compaq, for example. At its inception in 1982, Compaqs IBM killer value growth agenda was

perfect in focus, in sequence, on time, and flawlessly implemented. Compaq determined it

could produce the highest performing PCs with surprisingly low prices, thanks to strong engi-

Ted Moser and Hanna Moukanas are vice presidents of Mercer Management Consulting.

Moser is based in San Francisco and Moukanas is based in Paris.

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

3/14

2 Setting the agenda Mercer Management Journal

neering competence, a low-cost manufacturing culture, a dedicated PC focus, and (ultimately)

market share leadership. Compaq became an entrepreneurial star, breaking the business

worlds record for the fastest zero to $1 billion annual sales ramp-up in just five years.

Yet Compaqs value growth agenda didnt anticipate and evolve fast enough to capture the next

several profit shifts in the PC market. Value was migrating to made-to-order PCs (Dell), to serv-

ices-led computing solutions (IBM Global Services), and to enterprise computing (Sun, IBM).

Only after allowing competitors to gain value at its expense did Compaqs agenda changeand

then in all three directions at once. In 1998, within the space of ten months, Compaq rolled out

a variant of Dells distribution system, created a solutions sales force via the acquisition of DEC,

and started an enterprise server product line using DECs Alpha chip design. So much agenda

change in so little time starting so late created huge implementation challenges and failed to

drive a turnaround in value growth.

Todays most successful companies use a high-impact value growth agenda to keep pace with

or to stay one step ahead of Value Migration1, the process by which value growth opportunities

shift within and across sectors. Today, General Electrics agenda is defined as Globalization,

Services, Six-Sigma Quality, and e-Business. And its agenda has evolved over time. From thefamous Be #1 or #2 or get out market leader initiative in the early 1980s, through the Work-Out

program to enhance efficiency in the late 1980s, through the solutions and services efforts of the

1990s, GEs internal rate of change has kept pace with the market. Every GE manager and supply

partner knows these priorities and follows them. Investors, knowing and believing too, have

rewarded the company with exceptional value growth.

Value Migration changes the rules of the game

Just twenty years ago, most companies had less need for such a dynamic agenda. A company

was defined by what it produced, and everyone knew what it did. Nippon Steel, U.S. Steel, and

Usinor made steel. General Motors, Volkswagen, and Toyota made cars. BT, NTT, and AT&T

ran national telephone services.

Companies also competed in similar ways, typical-

ly relying on the same few levers to increase the

value of the firm. Winning strategies started with

a twin focus on product innovation to achieve dif-

ferentiation and cost reduction to maximize mar-

gins. Market share was the strongest underlying

value driver, as it led to scale economies in areas

such as R&D and branding and a low-cost positionthat preserved profit margins as an industry

matured and prices declined.

Managing the product portfolio for market share

and choosing new markets in line with internal

core competencies ensured sustained value

growth. A mostly silent partner in this approach

was the customer (Exhibit 2).

Market

sharestrategy

Product

portfoliomanagment

Productinnovation

Costreduction

Prof

itable

customerpurchases

Corecompetence

Exhibit 2 Traditional valuegrowth management

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

4/14

Mercer Management Journal Setting the agenda 3

An agenda centered on market share served business leaders well for decades, but it no longer

guarantees sustained value growth, for several reasons:

TSome scale positions have lost their uniqueness. Multiple competitors in global markets have

achieved adequate scale. Outsourcing providers have emerged to provide scale effects to

smaller competitors. Mass markets have given way to segmented ones, and product-based

value propositions to propositions based on solutions and customer economics (Exhibit 3).

TIndustry boundaries have blurred, creating new competitors who attack from the blind side. Being

the leader in telephony networks doesnt matter if customers want data networks. And for

many manufacturing applications, engineers consider the relative merits of metals, plas-

tics, and composites, suggesting a broader materials definition.

TCustomers have grown increasingly sophisticated, demanding, and diverse. The passive customer

has evolved into an active customer, seeking customized products and tailored solutions,

and wanting them promptly. With more options and more information on supplier econom-

ics, customers are armed and dangerous. Moreover, consolidation has made business cus-

tomers larger and more powerful. And the increasing heterogeneity of customers has creat-

ed huge incentives to build business designs precisely tailored to the priorities of economi-

cally attractive customer segments.

These changes have caused a dramatic increase in the rate and impact of Value Migration. With

the sources of competitive advantage having shifted from inside the enterprise to the marketplaceoutside, the task of the business leader has grown exponentially more difficult. Business success

is now determined by how well a company anticipates these shifts and by the speed with which it

mounts a winning response before the window of opportunity closes. Add to this more complex

environment an unprecedented level of pressure on managers to instill investor confidence in

their companys prospects, and the challenge of creating an effective value growth agenda

becomes fully evident.

0

10

20

30

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

Revenue ($ billions)

Chemicals 2000

DuPont

Dow Chemical

Hercules

Sigma-Aldrich

IMC Global

Revenue ($ billions)

Aerospace 2000

0

5

10

15

20

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

BoeingLockheed Martin

United TechnologiesGeneralDynamics

Textron

Returnonsales(%)

Returnons

ales(%)

Source: Mercer Value Growth Database

Exhibit 3 High revenues and market share no longer guarantee high profit.

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

5/14

4 Setting the agenda Mercer Management Journal

Finding the leverage

Every companys value growth agenda can be developed and organized around five growth levers

(Exhibit 4). Which levers to pull and in which order naturally varies by situation. The levers include:

TBusiness design innovation. Some of the largest

value growth opportunities involve the creation

of entirely new business designs responding tothe emerging needs of key customer segments

(see sidebar, Assembling the components of

business design). These new business designs

may supplant, complement, or be only loosely

related to the core business. The traditional

concern with market share remains important,

but subordinate. What makes sense is to maxi-

mize the share of healthy business designs.

The business design lever is particularly potent

when the future value growth potential of acompanys core business has matured or when

an industry is undergoing some form of funda-

mental change.

TCustomer value growth. Significant opportunities can be tapped by optimizing a companys

relationships with customers. In response to the fragmentation of the mass market and

the explosion of customer alternatives, the traditional focus on product innovation has

become part of an overall customer value lifecycle. Companies frequently have too many

of the wrong customers and too few of the right ones. Fine-tuning value propositions

offer, brand, pricing, distribution, and the customer experiencecan often attract more of

the most lucrative customers and change the economics of the rest. That can result inhuge financial rewards. Keeping value propositions in synch with the changing priorities

of customers through a test-and-learn culture can sustain these results.

TOperational breakthrough. The traditional focus on cost reduction has become part of an

overall operational breakthrough that optimizes cost, quality, time, and assets in the con-

text of the firms chosen value proposition. With business design lifecycles now increas-

ingly measured in years rather than decades, getting the operational side right cant wait

without compromising the total return to investors. In addition, operations today can be a

huge differentiator, enabling customers and suppliers to link with the company in new

and powerful ways.

TPortfolio redesign. Significant value growth leverage can often be found through a recon-

ceptualization and redesign of a company's portfolio. Yet traditional portfolio approaches

are ill-suited to the modern business environment, as they focus on business units and

seek to optimize a company's assets based only on the single dimension of product mar-

ket share, using rear-view-mirror metrics.

Taking other dimensions into consideration can lead to enhanced insights and better deci-

sions. One such dimension is business design, which enables the clustering of business

units into a smaller number of underlying designs across which lessons can be shared. This

Businessdesign

innovation

Portfolioredesign

Customervalue growth

Operationalbreakthrough

Organizationaltransformation

Product innovation Cost reduction

Market share Product portfolio

Custom

er

prio

rities

ValueMigration

Sou

rceso

fvalu

e

Exhibit 4 New value growth approach

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

6/14

Assembling the components of business design

Mercer Management Journal Setting the agenda 5

dimension incorporates the various types of customer relationships and profit models that

a company has. A second dimension is economic neighborhood, a concept that acknowl-

edges that traditionally defined industries are often parts of larger, more porous economiclandscapes. Mapping business designs across economic neighborhoods creates a broader

field upon which to see opportunities, threats, and potential moves.

TOrganizational transformation. This is perhaps the most important lever of all, since the

organization is the mechanism that transforms strategy into value growth. Pull this lever

when a good strategy is being held back by the organizationdearth of a critical capabili-

ty, inconsistent incentive systems, inefficient processes, dysfunctional culture, or unclear

leadershipor pull it when the current business design must be completely reinvented

to capture the next wave of value growth.

(1) Customer selection defines the set of cus-

tomers the company chooses to serve, as well

as those it chooses not to serve. Like other ele-

ments of business design, customer selection

may shift over time, sometimes dramatically:IBM, for example, has emerged as a major sell-

er of basic technology to computer manufac-

turers, turning former rivals into a new cus-

tomer set.

Value propositions define the value that the

company creates for customers. This may

include benefits derived from products, servic-

es, information, and other sources. The more

valuableeven uniquethese benefits are,

the more reasons that customers have to buy

from one company and no other.

(2) The profit model defines how the company

gets rewarded for the value that it creates for

customers. Profits may come from product sales

or service charges, as well as a host of other

value-capture mechanisms such as financing

income and licensing fees.

(3) Scope refers to how the company defines its

activities and its product and service offerings.

The right scope lets a company focus on what it

does best while allowing others to handle activ-

ities they do better, since the company is likely

to realize less value from those activities. Dell

Computer focuses on marketing and assembling

PCs and managing a complex supply network,

leaving to other companies the work of physi-

cally producing computer components.

(4) Strategic control refers to the companys abil-ity to protect its profit streams from being erod-

ed by competitors (or even by powerful cus-

tomers). It answers the questions, Why should

a customer buy from me? Why must a cus-

tomer buy from me? It may take many forms,

from ownership of patents without which a

particular technology cant be built to control

over customer relationships that determine

how buying decisions are made.

(5) Finally, organizational architecture defines

the management structures, corporate culture,

and talent leverage mechanisms that the compa-

ny uses to execute its business design choices.c

Customer selectionand valueproposition

Value capture/profit model

Strategic control Scope

Organizationalarchitecture

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

7/14

6 Setting the agenda Mercer Management Journal

Other major sources of value can cut across all these levers. For instance, digital technologies

including the Internet can help companies address critical business issues by offering signifi-

cant productivity improvements as well as making possible entirely new business designs and

value propositions.

Playing by the new rules

Rarely are all five levers pulled simultaneously. Typically, at any given time, one or two levers

predominate in a firms agenda, but over time, its agenda will evolve to focus on other levers

in response to changing market conditions. In any company, there are more laudable initia-

tives than available time; thus, prioritization and sequencing are the core arts of establishing

a value growth agenda.

Although value growth agendas require intensive efforts, they are well worth it.

Two examples should help make this clearer.

Wal-Marts value growth agenda

Wal-Mart is one of the greatest value growth stories of all time. Starting in 1969 as a local

supermarket in Arkansas, the company has created over $200 billion in value for shareholders.

Between 1989 and 1998 alone, it represented nearly a quarter of the $726 billion in sharehold-

er value created in the retail industry.

There are four major phases in the evolution of Wal-Marts value growth agenda:

TCapturing markets for one. Sam Waltons initial idea was as bold as it was simple. He

wanted to be the discount retailer for all of Americas small-to-medium-sized towns,

which can only support a single superstore. These markets for one conferred a natural

monopoly on the first retailer to the market. Walton aggressively built out a nationwidechain to ensure that Wal-Mart would be there first. A brilliant business design innova-

tion, these stores remain a bedrock of the firms financial performance to this day.

TStreamlining operations through real-time logistics and decision management. For much of the

1980s and 1990s, Wal-Mart made significant technology investments in electronic data

interchange, the automation of distribution centers, and the implementation of satellite

systems to facilitate ordering, shipping, logistics, and communications. But what really

mattered was how fast Wal-Mart acted on that data. In the store, management focused

on capturing point-of-sale information and mining this data for insights. In addition,

they worked to transform their logistics relationships with suppliers. These initiatives

have helped Wal-Mart achieve an operational breakthroughextraordinary growth with

increasing inventory turns and a competitively superior return on assets (Exhibit 5).

TExtending into new formats and product lines. By the mid-1980s, it became clear to Wal-Mart

that it had a huge value gap. Its stock valuation was not justified by the profit growth

potential of its core store formats, which was tapping out as U.S. markets approached

saturation. So the mid-1980s through the 1990s became a time of exceptional business

design innovation and experimentation for Wal-Mart. Its Sams Club format focused on

new customer segments such as small business owners and budget-oriented con-

sumers by delivering a focused assortment of bulk items in a warehouse club format.

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

8/14

Mercer Management Journal Setting the agenda 7

Source: Mercer Value Growth Database

Inventory levels as % of sales

0

2

4

6

8%

1990 '92 '94 '96 '98 '00-5

0

5

10

15

20%

1990 '92 '94 '96 '98 '00

Inventory turnover Return on assetsCAGR

1990-2000

Wal-MartK Mart 2.6%

Target

Target -1.0%

K Mart

0

5

10

15

20

25%

1990 '92 '94 '96 '98 '00

Wal-Mart -4.5%

Target -1.6%

K Mart -2.1%

CAGR1990-2000 Wal-Mart 3.8%

Exhibit 5 By streamlining operations, Wal-Mart improved inventory turns and ROA.

Its Wal-Mart Supercenters focused on new purchase occasions such as grocery shopping,buying prescription drugs, and photo finishing. Management focused as well on interna-

tional expansion of culturally tailored versions of its successful U.S. business designs.

While the jury is still out on its international moves, Wal-Marts new formats effort has been a

huge success. In 1990, new formats represented less than 10 percent of Wal-Marts stores; by the

end of 2000, they represented over 50 percent.

TOrganizing for a consistent customer experience. In the early 1990s, Wal-Mart recognized that

its nearly one million workers represented both a huge risk and a huge opportunity. The

question was how to maintain a consistent corporate culture and customer experience in

a low-wage industry with relatively unskilled labor and high turnover rates. The companyis working to achieve this organizational transformation in a number of ways, including:

- establishing rules of customer engagement such as the friendly greeter at every entrance

and the ten-foot rule that ensures that an associate acknowledges the presence of any

customer who comes within a ten-foot radius

- offering both incentive compensation to reward initiative and a healthy benefits package

to strengthen the basic employment relationship

- sending senior management into the field every week to talk with store managers,

associates, and customers

Through such procedures, Wal-Mart has earned the cooperation of its associates and

has engaged their emotional energy.

Sustaining this exceptional performance (Exhibit 6) will be a challenge. Enhancing the interna-

tional business and leveraging the Internet should both figure prominently in Wal-Marts next

agenda.The company is already at work on a number of Internet initiatives, both customer-facing

(Walmart.com) and supplier-facing. As Wal-Marts e-commerce moves have disappointed to date,

the firm may have to make a big e-commerce acquisition as part of defining the next agenda.

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

9/14

8 Setting the agenda Mercer Management Journal

$

billions

CAGR(1981-2001)1. 1980s-mid-1990s

Streamline logistics, distribution, and supplier network

2. Mid-1980s-mid-1990sPioneer new formats and product lines

3. 1990sDeliver a consistent customer experience

Businessdesign

innovationPortfolioredesign

Customervalue growth

Operationalbreakthrough

Organizationaltransformation

1

2

3

0

50

100

150

200

250

1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999

Wal-Mart 30%

Target 18%

Kmart 3%

2001

Note: Q1 1981- Q1 2001

Source: Mercer Value Growth Database

Exhibit 6 Wal-Marts evolving agenda

LVMHs value growth agenda

LVMH, the leading global purveyor of luxury goods, has created more than $25 billion in sharehold-

er value in the past ten years by artfully initiating three important shifts in its value growth

agenda (Exhibit 7):

TIndustrializing the luxury branded experience. LVMH recognized that the value growth potential

of the classic boutique business model was inherently limited. Starting in the early 1990s

under the leadership of Bernard Arnault, LVMH invested heavily in advertising and in open-ing more and larger stores across which to amortize its brand investments. From the begin-

ning, the strategy was based on moving beyond the traditional carriage trade to capture

more aspirational customers. That move took high-end brands to what approached a mass

market, without diluting their cachet. The focus on brand has continued as the company

has expanded. Some brands were moved up-market (such as Veuve Clicquot), others

extended (Diors move into high-end fragrances), and yet others energized with new talent

(Givenchys hiring of designer Alexander McQueen in 1996).

TCornerstoning to capture a greater share of wallet. Wanting to capture a greater share of

the target customers luxury goods spending, starting in the mid-1990s, the company

embarked on a major expansion along three dimensions. First, it reinforced the core port-

folio of brands in fashion, leather goods, fragrances, cosmetics, wine, and spirits with key

acquisitions (Marc Jacobs) and alliances (Prada). Second, it moved into multi-brand retail

(Duty Free Shops and the fragrance and cosmetics superstore Sephora). And third, it

expanded into adjacent economic neighborhoods (watches and jewelry). Through these

portfolio redesign moves, LVMH has captured the leading position in terms of total operat-

ing profit in three of its sectors (leather goods, specialty retailing, and wines and spirits)

and the number three position in two others.

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

10/14

Mercer Management Journal Setting the agenda 9

CAGR(1990-2000)

$

billions

1. 1990sIndustrialize the luxury branded experience

2. Mid-1990sCornerstone into adjacent economicneighborhoods

3. 1997Integrate to control distributionchannels

Businessdesign

innovationPortfolioredesign

Customervalue growth

Operationalbreakthrough

Organizationaltransformation

1, 3

1

2

*Gucci CAGR is 1996-2000; Hermes CAGR is 1994-2000.

Source: Mercer Value Growth Database

0

10

20

30

40

50

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000

LVMH 13%

Seagram 10%

Gucci 23%*

Hermes 22%*

Brown-Forman 7%

2001

Exhibit 7 LVMHs evolving agenda

TIntegrating to control distribution channels. Starting in 1997, LVMH embarked on another

business design innovation: to solidify its brand positions by increasing both its num-

ber of outlets and its level of control over brand imaging at retail. Beginning with the

rapid expansion of its flagship boutique stores (Louis Vuitton, Celine, and Loewe),

and continuing with its acquisition of Duty Free Stores to provide access to both Asian

markets and a new travel-related purchase occasion, the company has moved aggres-

sively to be where its high-end customers are. Recent moves into mass retailing, such

as its acquisition and expansion of Sephora, and into the Internet space througheluxury.com, provide LVMH with retail control over a significant portion of its product

sales and ensure a great customer experience. Contrast these moves with several other

fashion houses that chose to mass license their brands, only to see the value of those

brands diluted a short time later.

Setting and communicating the agenda

Wal-Mart and LVMH could have made other choices. Each company was and remains confronted

with a huge spectrum of strategic options. But each chose to focus the limited financial, physical,

and emotional energies of their organizations on a few key initiatives that matteredtransforming

a small town supermarket into a chain of superstores, then a retail occasion phenomenon, and aluxury retailer into a portfolio of powerful brands. And they renewed this agenda as new opportu-

nities and threats arose, thereby delivering sustained and superior economic performance.

Setting the right course is hard. Montgomery Ward and Kmart had access to the same data and

made vastly different and less effective choices in discount retail. And in the fashion space, The

Limited could have taken a similar approach to that of LVMH for The Limiteds own mid-market

customer, but didnt.

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

11/14

10 Setting the agenda Mercer Management Journal

While setting and renewing a value growth agenda is not easy, the benefits clearly justify

investing time in its development. There are four key steps in establishing an agenda:

T Identify and assess the impact of Value Migration patterns in economic neighborhoods served.

In order to develop an accurate assessment of the value growth potential of an enter-

prise, its crucial to have a clear perspective on where tomorrows profit zones will

emerge in all economic neighborhoods served or potentially served. An evaluation of

which Value Migration patterns3 are likely to play out is often the best way to create a

shared vision of future competitive dynamics, threats, and opportunities for the business

designs the company currently operates.

TEvaluate the value growth potential of current initiatives. Its critical to assess the value

growth potential of all current initiatives in light of the management teams shared

insights into future sources of value. Inevitably, some initiatives will see their potential

soar, while others plummet. Comparing the net value growth potential of all initiatives

with the enterprises stated value growth goals will identify the value gap, if any, that

the organization must address.

TDevelop new growth hypotheses. Whether or not a value gap exists, management should

hypothesize which new movesfrom redesigning the portfolio to creating an innovative

business design, achieving operational breakthrough, or building a better customer value

growth systemwill move the company from strategic disadvantage to strategic advan-

tage. Then they should estimate the value growth potential of each significant hypothesis.

T Define the value growth agenda. Armed with a menu of potential moves and their potential

value impact, the agenda-setting process begins. What combination of initiatives

whether focused on reinvention or operational improvementin what sequence over

what timeframe maximizes the firms value growth within the constraints of executive

attention and capital availability?

Once the agenda has been set, the truly hard job begins. Responsibilities and deadlines must be

established. The value growth agenda must be led from the top. And it must be communicated

early and often to employees, investors, customers, and suppliers. In time, it will become the DNA

of the company and direct a creative organization toward great results. Suppliers and customers

who buy into the agenda will respond more positively and help the firm succeed. Investors who

understand it will support the share price, maintain lines of credit, and resist demands for hasty,

shortsighted moves in an economic downturn or after a bad quarter.

The value growth agenda must remain attuned to the marketplace and thus needs to be renewed

periodically. Changing market conditionswhether macroeconomic, such as an economic downturn;technological, such as the emergence of the Internet; customer-oriented, such as the emergence of

a new segment; or competitive, such as the identification of a new competitor on the edge of the

radar screenwill call for a review, as will the initial signs of Value Migration that threaten the

current business design.

Creating value is easier in good economic times as a rising tide lifts all boats. But with slowing

macroeconomic growth, a value growth agenda based on real strategic insight, on time, in the

right sequence, and flawlessly executed will be a competitive necessity. Times like this represent

a great opportunity. While rivals struggle to regroup, great companies mobilize, disrupt the

rhythm of competition, and seize control of their markets.c

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

12/14

Mercer Management Journal Setting the agenda 11

As you consider building your own Value Growth Agenda,

ask yourself the following questions:

Competitive position

T Is our market value

growing as fast as it

could?

T Do investors value

our company fairly?

T Are we as profitable

as our toughest

competitors?

T Are we meeting our

revenue and earn-

ings growth targets?

T Have we created

barriers to entry for

new entrants in our

industry?

T Can we pinpoint

why customers

choose us overour competitors?

Patterns and trends

T Do we regularly

track changing

customer

and technology

trends, emerging

patterns, or new

regulations in the

industry?

T How is our business

threatened by these

changes?

T How are new

entrants redefining

the traditional rules

of success in our

industry?

T Is our competitive

radar screen

tracking new,

digitally enabledplayers?

T How are the tradi-

tional boundaries

of our industry

blurring?

Growth strategy

development

T Are our strategic

goals and financial

targets ambitious

enough?

T Do senior managers

dedicate time to

think about and

develop new growth

opportunities?

T

Do we have a clearset of initiatives to

improve our current

businesses?

T Do we have an

attractive set of

growth ideas to

develop future

businesses?

T Is our growthstrategy driven

by customer priori-

ties rather than

by internal core

competencies?

T Do we know which

growth initiatives

will create value

beyond what ana-

lysts have already

factored into our

market value?

T Do we have realistic

and action-oriented

plans to realize

these growth initia-

tives?

Growth strategy

communication

T Do employees and

managers have a

clear understanding

of our growth

strategy?

T Are they excited

and motivated by

that strategy?

T Are we clearly

communicatingthe strategy to

investors?

T Are investors

confident in our

ability to grow?

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

13/14

Mercer Management Journal

Editorial Board

James W. Down

Charles Hoban

Nancy Lotane

Joseph Martha

David J. Morrison

Ted Moser

Hanna Moukanas

Patrick A. Pollino

Phyllis Rothschild

Adrian J. Slywotzky

Mercer Management Journal is published by Mercer Management Consulting for its clients and friends.

The contents are copyright 2001 and 2002 by Mercer Management Consulting.

Value Migration is a proprietary trademark of Mercer Management Consulting that has

been registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. NexperimentTM is a trademark;

Strategic Choice Analysis is a registered trademark; Value Net Design SM is a service mark;

and ChoiceboardSM is a service mark; all owned by Mercer Management Consulting.

Cover illustration by Patrick Corrigan.

All rights reserved. Excerpts can be reprinted with attribution to Mercer Management Consulting.

Articles can be found on our Web site: www.mercermc.com.

For information on reprinting entire articles and all other correspondence, please contact the editor:

John Campbell

Mercer Management Consulting

33 Hayden Avenue

Lexington, Massachusetts 02421

781-674-3323

Director of Publications

John Campbell

Art Director

Michael Tveskov

Digital Edition Team

Ellen M. Zanino

Christopher Hogan

Jamie Klickstein

-

8/9/2019 The Value Growth Agenda

14/14

About Mercer Management Consulting

As one of the worlds premier corporate strategy firms, Mercer Management Consulting

helps leading enterprises achieve sustained shareholder value growth through the development

and implementation of innovative business designs. Mercers proprietary business design tech-

niques, combined with its specialized industry knowledge and global reach, enable companies

to anticipate changes in customer priorities and the competitive environment, and then design

their businesses to seize opportunities created by those changes. The firm serves clients from22 offices in the Americas, Europe, and Asia.

Beijing

Suite 1825B, Tower 2,

Bright China Chang An Building

7 Jianguomennei Avenue

Beijing 100005

86/ 10 6510 1758

86/ 10 6510 1759 fax

Boston

33 Hayden AvenueLexington, Massachusetts 02421

781 861 7580

781 862 3935 fax

Buenos Aires

Florida 234, piso 4

1334 Buenos Aires

54/ 11 4394 6488

54/ 11 4326 7445 fax

Chicago

10 South Wacker Drive

13th Floor

Chicago, Illinois 60606

312 902 7980

312 902 7989 fax

Cleveland

One Cleveland Center

1375 East Ninth Street, Suite 2500

Cleveland, Ohio 44114

216 830 8100

216 830 8101 fax

Dallas

3500 Texas Commerce Tower

2200 Ross Avenue

Dallas, Texas 75201

214 758 1880214 758 1881 fax

Frankfurt

Friedrichstr. 2-6

D-60323 Frankfurt

49/ 69 17 00 83 0

49/ 69 17 00 83 33 fax

Hong Kong

NatWest Tower, 32nd Floor

Times Square

One Matheson Street

Causeway Bay

Hong Kong

852/ 2506 0767

852/ 2506 4478 fax

Houston1136 North Kirkwood

Houston, Texas 77043

281 493 6400

281 754 4328 fax

Lisbon

Av. Praia da Vitria, 71-5.C

(Edifcio Monumental)

1050 Lisboa

351/ 21 311 38 70

351/ 21 311 38 71 fax

London

1 Grosvenor Place

London SW1X 7HJ

44/ 20 7235 5444

44/ 20 7245 6933 fax

Madrid

Paseo de la Castellana, 13-2 piso

28046 Madrid

34/ 91 531 79 00

34/ 91 531 79 09 fax

Mexico City

Paseo de Tamarindos 400-B

Piso 10, Bosques de las Lomas

05120 D.F.

52/ 55-5081 900052/ 55-5258 0186 fax

Montral

600, boul. de Maisonneuve Ouest

14e tage

Montral, Qubec H3A 3J2

1/ 514 499 0461

1/ 514 499 0475 fax

Munich

Stefan-George-Ring 2

81929 Mnchen

49/ 89 939 49 0

49/ 89 930 38 49 fax

New York

1166 Avenue of the Americas

New York, New York 10036

212 345 8000

212 345 8075 fax

Paris

28, avenue Victor Hugo

75116 Paris

33/ 1 45 02 30 0033/ 1 45 02 30 01 fax

Pittsburgh

One PPG Place, 27th Floor

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222

412 355 8840

412 355 8848 fax

San Francisco

Three Embarcadero Center

Suite 1670

San Francisco, California 94111

415 743 7800

415 743 7950 fax

Seoul

5th Floor

Woori Investment Bank Bldg.

826-20, Yeosam-dong,

Kangnam-ku

Seoul, 135-935

82/ 2 3466 3100

82/ 2 3466 3105 fax

Toronto

BCE Place

161 Bay Street, P.O. Box 501

Toronto, Ontario M5J 2S5

416 868 2200416 868 2208 fax

Zurich

Tessinerplatz 5

CH-8027 Zurich

41/ 1 208 77 77

41/ 1 208 70 00 fax

Internet

www.mercermc.com

www.howdigitalisyourbusiness.com