(Nazis, Nazis and more Nazis) By: Jimmi Reaza and Mireya Victorio.

The Unholy Alliance - Du Pont, GM and the Nazis

-

Upload

fileandclaw322 -

Category

Documents

-

view

304 -

download

1

description

Transcript of The Unholy Alliance - Du Pont, GM and the Nazis

-

Until 1963, Du Pont, America's leadingchemical maker, dominated General Mo-tors, theworld's largest automanufacturer,through stock ownership and directors,Lammot du Pont, who was both chairmanof GM and president of Du Pont, was prob-ably America's most important industrial-ist during the two decades between theFirst and Second World Wars. He was inti-

mately allied with far-right causes duringthe 1930's,which in some circles gave himthe reputationof a superpatriot.(At the timeof his death in 1952, he still held $28,000in unpaid loans to the American LibertyLeague.)

However, in Germany afterWorld War II,he was thought of by some Nazis as afriend. In a formerly secret intelligence re-port contained in the files of the militaryoccupation government that is now in theNationalArchives, this reputationis spelledout graphically.

The report discloses a conversation thatwas held in a military prison betweenGeorg von Schnitzler, Paul Hoefliger, andGunther Frank-Fahle, who were jailed aswar criminals for the part they played asexecutives of I. G. Farbenindustrie, thegiant German explosives and chemicalcombine which manufactured the poisonfor Hitler's gas chambers. The three werehunting for an escape plan and they hit onLammot du Pont as someone who "could'be depended upon to intervene in theirbehalf," according to the report.

A member of the du Pont family was anobvious choice for the Farben executives.

The Du Pont Company had an intimate re-lationship with Farben dating from 1926.As a result of this close association, cre-ated throughscores of business deals andjoint venturesaround theworld, these Farb-en executives knew that Du Pont had:

Surrendered the fruits of its researchand technical know-how in a handful of

74 PENTHOUSE

agreements negotiated on the eve of thewar. These included Freon for refrigeration(from the Du Pont-General Motors jointventure, Kinetic Chemicals), nylon, andsynthetic rubber.

Helped disguise Farben patents sothatAmerican authorities would think theywere Du Pont patents.This prevented theirseizure as alien property.

Owned over $2 million worthof sharesof Farben stock. Farben, in turn, owned$838,412.50 in Du Pont stock, accordingto records captured by the U.S. militaryauthorities.

Helped German munitions makersvio-late the treaty that ended World War I bykeeping silent about the illegal trade inmunitions conducted by German firms.Du Pont went so far, according to a for-merly secret wartime Justice Departmentreport, that it purchased over 11,000shares of stock in two German arms mak-ers to aid the firms in "consolidating theirposition and business in Germany."

Put secret trade agreements beforenational policy by refusing to sell tet-racene-primed ammunition to Great Brit-ain in 1940 ata time when the British were

begging-American aid and PresidentRoosevelt had declared the U.S. to be an"arsenal for democracy."

But I. G. Farben was nottheonly Germanmunitions maker with which Du Pont haddealings that caused concern amongAmerica's war policy makers. A telegramsent to the State Department on March 21,1942, some three months after the U.S.declared war on Germany, caused secretshock waves. The telegram was from theU.S. legation in Bern, Switzerland (a keyEuropean listening post swarming withmembers of the U.S. intelligence commu-nity, including Allen Dulles, who was tobecome head of the CIA). It reads:

"The following just received with spe-

cial request that French sources be not(repeat, not) disclosed.

"Representatives of Du Pont de Ne-mours recently metwith representatives ofHermann Goring Works. Meeting com-menced at Montreux but has moved to St.Moritz for greater privacy.

"In reply to informal inquiry by my infor-mant, high Swiss Foreign Office officialreadily confirmed the report adding thatthis was not the first time the parties hadmet; that Vichy was fully informed; and inconclusion reminded my informant thatone of the president's sons had married adu Pont."

A notation in the State Department filesindicates that a paraphrase of the cablewas turned over to the Federal Bureau ofInvestigation "in strict confidence." FBIfiles and documents prepared during thisperiod remain classified.

(The mention of the du Pont-Rooseveltmarriage was a reference to the weddingof Ethel du Pont, daughter of Eugene duPont, Jr., and Franklin Roosevelt, Jr., thepresident's son. The marriage ended indivorce.)

The Hermann Goring Works controlledhundreds of manufacturing firms through-out Nazi-occupied Europe. Itwas Europe'sleading coal supplier and the secondlargest steel producer. Its armament divi-sion absorbed many of Europe's leadingmunitions makers. The huge conglomer-atewas designed to aid the Nazis inattain-ing the goals of Hitler's four-year plan ofincreased production for German re-armament.

Itmustbe stressed thatthe Du PontCom-pany had for years maintainedsuch a closerelationship with the U.S. military that in-dustry officials saw the company as "al-mosta subdivision" of theWar Department.As early as 1919, U.S. officials agreed togive Du Pont unique access to secret gov-

-

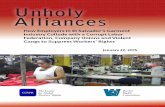

WHAT WAS GOOD FOR GENERAL

MOTORS WAS GOOD FOR THE

COUNTRY ... EVEN IF IT MEANT

CONTRIBUTING TO THE NAZI

WAR MACHINE IN EUROPE!

ernment military research.(Germanywas not the only enemy coun-

try with whom Du Pont had dealings.Another dispatch in State Departmentfilesdetails the 1943 offering for sale in Italy,through agents, of a patent owned by DuPont which covered a process to treatmetal-something that had possible stra-tegic value to the Italians.)

Top State Department officials wereeven more concerned about the activitiesof Du Pont's General Motors, however.Papers in the National Archives disclosethatthese government officials suspectedthatkey GM executives were pro-Nazi andthat their proclivities were behind the au-tomaker's secret trading with the enemy.

Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A.Berle, Jr., in 1941 expressed his views onGM Vice-President Graeme K. Howard to a

colleague in a short memo. Howard, saidBerle, "was endeavoring to defend theright of General Motors to maintain Axispropagandists as agents in SouthAmericaon the ground that 'General Motors couldnot become concerned in political prob-lems.'" Howard had written a book de-

fending Nazi aggression in Europe andargued that the U.S. should acknowledgeNazi hegemony.

A second General Motors vice-presi-dent and director, James D. Mooney,came under suspicion somewhat later. Astill-secret communication from the chiefwartimecensor in Canada tothe U.S. StateDepartment reveals an intercepted letter.This letter,according to a description of itin archive records, led the censor to feelthat "Mr.Mooney of GM is pro-German."Censorship intercepts were sealed underpresidential order and cannot be madepublic.

In a "strictly confidential" note, datedMay 31, 1941,noteto FBI Director J. EdgarHoover, Assistant Secretary Berle re-

quested "a most discreet investigation beconducted of Mr. Alfred P.Sloan, Presidentof General Motors Corporation; Mr. How-ard, vice-president of thatcorporation andpresident of General Motors Export Com-pany; and Mr. James D. Mooney, who isconnected with the General Motors orga-nization."

The trio were all directors of GM andGM's German subsidiary, Adam Opel A.G.Sloan had made knownhis feelings towardthe Nazis when he reportedly told a groupof stockholders in 1939 that the war inEurope, soon to engulf the world, was a"petty international squabble."

When the U.S. clamped down on Ameri-can corporate relations by prohibitingtradewith foreign firms owned or managedby Germans or Nazi sympathizers, GMtried to thwart the blockade.

In Bolivia, according to a May 31, 1941,telegram, the U.S. legation had been told"in extreme confidence" that "arrange-ments are being made between GeneralMotors Export Corporation and Gundlach[C.F. Gundlach, who also represented DuPont interests in Bolivia] pro-totalitarianagent for that company in Bolivia, so thatbusiness may be operated nominallyunder the name of Viuda Velez de Otero."

In Guatemala, the U.S. Naval attachereported in a secret intelligence report ofFebruary 14, 1941, that GM's replacementfor a pro-Nazi firmwas a "salesman namedMontano" who was financed by Germanbankers.

A series of similar attempts to violaterestrictions on trading with the enemybrought another State Department call fora "thorough" FBI investigation of Mooneyand General Motors Export Corporation.The June 8, 1942 memo alludes to "previ-ous grave suspicions attaching to thedealings" of the firm.

In June 1943 the previous suspicions

were confirmed. The State Departmentcaught GM trading with the enemy. Theviolation, as spelled out in a series of con-fidential cables, showed that GeneralMotors' Swiss subsidiary had importedthousands of dollars of material fromenemy territory. Moreover, GM also con-tinued to receive sales figures, transmittedthrough its office in Switzerland, for carsand trucks sold behind enemy lines. TheState Department looked askance at thepractice.

State Departmentofficials kept on top ofGM affairs through secret telegrams senttothem fromallover theworld. But particu-lar attentionwas drawn to the activities ofGM's Opel subsidiary in Germany. Opelbegan aiding Hitler's bloody drive forworld domination as early as 1935, sixyears before Germany declared war on theUnited States.

In 1935 GM built a large modern plant inBrandenburg, about 200 miles from themain Opel plant at Russelsheim. "TheBrandenburg works was built ... at the in-stigation of the [German] government withthe object of building military cars andtrucks and heavy commercial vehicles,"states a formerly secret British wartime re-port on Opel. The vehicles produced atBrandenburg became, in the words of anAmerican intelligence report, "the back-bone of the German Army transportationsystem."

By the late 1930's the modern conveyorbelts at Brandenburg and at the recentlyenlarged Russelsheim factories werewhirring smoothly-but not with the preci-sion and speed desired by the Nazis. InNovember 1938the German auto industry,including Ford and Opel, was called to aspecial meeting with Field Marshal Her-mann Goring. A memo on the meeting iscontai ned in a confidential report pre-pared by thewartime U.S. Justice Depart-

75

-

ment.The memo,writtenby Dr. H. F.Albert,chairman of Ford Motor Company's Ger-man operations, reveals Nazi unhappi-ness that "the German automotive indus-

tries had not met the expectations placedin them." According to the mef!lo, Goringdressed down the automakers for produc-ing "too expensive cars, much too heavyunits" which "were not fit, in their presentcomposition, to carry through the increasein production which, for military reasonsappears necessary." Automakers' profitsof from 40 to 50 percent were also criti-cized by Goring.

Goring also went on to tell the automak-ers, according tothe memo, that"the forti-fication of the western frontiers could nothave been carried through if Americanunitshad notbeenrevertedto.These Ameri-icancarshadmetall theexpectationsplacedin them." Ford and GM produced the bulkof the trucks for the Nazi military.

GM's Russelsheim plant was convertedinto a large-scale aircraft-parts factory in1939, and a year later it was the leadingproducer of components fortheGU-88, theLuftwaffe'smost important bomber. Half ofthe propellant systems for this aircraftwere assembled during the war at Rus-selsheim. The facility also assembled jetengines for the world's first jet fighter, theME-262.

General Motors retained control of itsGerman factories untiI the spring of 1941when Cyrus Osborn, chairman of Opel'sboard of managers and the firm's chiefoperating executive, returned to America.Carl Luer, a former member of the GM-selected board of directors, was named astrustee a year later.

Before the outbreak of hostilities, Chair-man Alfred P. Sloan, a Du Pont Companydirector, was an Opel director, along withGraeme K. Howard, James D. Mooney,and David F.Ladin, all GM officials. Opel'sfounder, Wilhelm von Opel, continued aschairman of the Opel board. His son Fritz,jailed in the U.S. during the war as anenemy alien, had been a GM director inDetroit untiI 1938.

Although its German factories were ob-viously important to the Nazi war effort,General Motors had already made an evenmore basic contribution to the conflagra-tion that engulfed Europe. In 1935 it wentinto business with I. G. Farben makingtetraethyl lead, the chief ingredient inhigh-octane gasoline. This was the firsttime the antiknock compound had beenproduced outside the United States sinceitwas discovered in 1921by GM's CharlesKettering.

The venture-joined by Exxon, thenknown as Standard Oil of New Jersey-was essential if petrOleum-shortGermanywas to mount a war. "Without lead-tetra-ethyl," a captured I. G. Farben wartimedocument explained, "the present methodof warfare would be unthinkable."

When part of the story of GM's aid to theNazis was made public in 1974, testimonybefore the U.S. Senate by Bradford C.

76 PENTHOUSE

Snell, a Senate.antitrust subcommitteecounsel, General Motors reacted angrily."Following the German declaration of waron the United States on December 11,1941," GM said in a prepared statement,"the relationship with Opel was entirelysevered. No Americans sat on the board of

directors, even nominally, afterthattime."However, documents in the National Ar-

chives disclose that General Motors wasable to retain some measure of control

over Opel-even during the war. This wasdone through Albin D. Madsen, a wartimedirector of Opel, who represented GeneralMotors, according to a 1948 report by theU.S. military's decartelization branch.

Madsen was managing director of GM'ssubsidiary in Denmark,General Motors In-ternational, according'to a company his-tory prepared by the American legation inStockholm, Sweden, in March of 1944.

The report discloses that after Denmarkwas overrun by the Nazis in April, 1940,GM's plant was notseized as the propertyof enemy al,iens and run by a German-ap-pointed trustee as the Opel plants were inGermany. On the contrary, GM continuedto runthe factorywithoutGerman interven-tion untiI early 1943, according to the re-port. The GM management in Denmarktried to put off Nazi overtures with argu-ments that"consideration should be giventothefact of theAmerican ownership of thecompany," the report explains.

State Department officials, relying oncompany managers for much of their in-formation, tell of a set of complex negotia-tions which led to GM's relinquishing itsnew factory in Copenhagen to the Ger-mans. The terms made it appear that theNazis had used force; but in fact the GMfactorywas in effectrented to theGermansthrough the Danish government. The Ger-mans used it as an aircraft engine repairfacility. GM retained complete control overall its remaining manufacturing facilities inDenmark, according to the report.

Inorder to protect itswartime profits, thereport notes, GM "purchased a ... realestate company which owned a largeblock of modern flats in Copenhagen" inmid-1943. Th is was just one stratagemused by the GM-Du Pont complex to squir-rel away Nazi war profits.

GM officials claimed in 1944 that theyhad resisted German entreaties as long aspossible, but, the reportacknowledges, "aconsiderable section of the Danish popu-lation views the company as undesirableby reason of the fact that many peoplebelieve it cooperated with the Germans inmaking available its plant."

Protecting Nazi war profits was difficultfor America's premier corporations duringWorld War II. GM's scheme of keeping themoney under its control in the foreigncountry untiI after theend of hostilities wasonly one method.

After the war ended both Du Pont andGM made attempts to reap the rewards oftheir corporations' silent dealings with theNazis. General Motors, for instance, was

successful in obtaining morethan $16 mil-lion in direct awards and another $16.8million in tax savings as a result of bomb-ing damage to its German war plants.

DuPont, without damaged plants to col-lect on, went to the Foreign Claims Settle-ment Commission in an attemptto get itsshare of profitson wargoods sold tothe Na-zis by firms it partially owned in Germany.

The largest single pile of German warprofits that Du Pont tried totap was held bythe German Foreign Debt Conversion Of-fice. The money, $121.407.39, accordingto Du Pont, consisted of dividends from amajority interest in Duco, AG, of Berlin, ajoint ventureDu Pont owned withSchering,AG, Germany's second largest chemicaland pharmaceutical firm. Although Sche-ring had control of 51 percent of the votingshares of the company, Du Pont ownedadditional nonvoting stock which gave itamajority of the profits.

The profits Du Pont attempted to collectthrough the commission represented re-turns for the years 1940 through 1943. Butin 1967 the claims commission rejectedDu Pont's bid for the money becauseawards could be granted for damagedproperty but not for debts.

Du Pont also tried to collect $15.494.50in royalty payments for the use of its syn-thetic rubber patents in Czechoslovakia.Under the licensing arrangement, BataCorporation was to pay Du Pont $35 a ton.The corporation produced 442 tons for theNazis, but the commission again thwartedDu Pont's lust to collect enemy war profits.

Du Pont also attemptedto collect royal-ties through the State Department for pay-ments on war material produced by I. G.Farben. The German firm was taken overby Allied military authorities after the warand Du Pont could only be compensatedby appealing to the U.S government. DuPont expected thousands of dollars in prof-its as a result of patent arrangements withI. G. Farben. Available records do not in-dicate whether the company was paid.

Du Pont had agreements with othercompanies producing war goods for theNazis. Nylon patent rights had been soldon the eve of World War II by Du Pont inGermany, Italy, and F!ance. How muchwas collected in wartimeprofits fromtheseconcerns is unknown since it was not nec-

essary for Du Pont to take formal actionwith the U.S. government to collect themoney. Presumably, the firms paid whatDu Pont demanded as its share figuredunder contracts negotiated beforethe war.

Du Pont also owned shares in a numberof importantAxis firms. Aside fromstock inI. G. Farben, Du Pont held about 4 percentof the stock of Deutsche Gold and SilberScheideanstalt. Nicknamed DEGUSSA,the firm was second only to I. G. "in therange, variety,and importance of its manu-facture of chemical products," accordingtoan assessment made bymilitaryauthori-

.ties after the war. Du Pont valued its DE-GUSSA shares at $430,066.18 in 1930.

A list of foreign investments datedCONTINUED ON PAGE 91

-

"I think we could safely rule out suicide, Watson,"

.'

UNHOLYALLIANCECONTINUED FROM PAGE 76

January 24, 1944, supplied to the StateDepartmentby Du Pont, showed holdingsin French and Italian chemical industries.In France, German-occupied during thewar, Du Pont owned 17.5 percent of the

" stock in Societe FranQais Duco, an outfitmanufacturing Du Pont paint productssimilar to the German Duco firm.

Du Pont also maintained an interest in

the Italian chemical giant, Montecantini, a'firm which historians say had a large rolein bringing about the fascist dictatorshipof Benito Mussolini. Du Pont also held 16percent of the stock in Societa ItalianaDelle Celluloide, a holding company inwhich the firm had maintained a control-ling interest prior to the war,

In addition to making money, these for-eign investments had an indirect benefitfor Du Pont. They helped the company di-vide the world into exclusive markets inwhich there would be no competition,

These formerly secret government doc-- uments help cast light on the hidden re-

cesses of American corporate activity intimes of international tensions, They showthe actions behind the business axiomformulated by Pierre du Pont, the patriarchof the modern American corporation. "Wecannot assent to allow our own patriotismto interfere with our duties" to achieve"reasonable profits for our stockholders,"he said in testimony before the SenateCommittee to Investigate the Munitions In-dustry in the 1930's,

"It may,of course, be argued thatpartic-ipating in both sides of an internationalconflict, like the common corporate prac-tice of investing in both political partiesbefore an election, is an appropriate cor-porate activity," says Senate Aide Snell ina study done for the Senate antitrust andmonopoly subcommittee, "Had the Naziswon, General Motors, .. would have ap-peared impeccably Nazi; as Hitler lost,these companies were able to reemergeimpeccably American, In either case, theviability of these corporations and the in-terests of their respective stockholderswould have been preserved,"

Snell, however, sees the inevitability ofthe conflicting loyalties created by this

, credo as having a "potential for abuse"

r' ,which would suggest "that in the case ofpowerful concentrated industries en-gaged in war-convertible production mul-tinational expansion may adversely affect

j' America's legitimate interest in national, security,"

A special report by the Foreign Econom-ic Administration prepared in 1945 cameto similar conclusions about the activitiesof multinational corporations. It based its

\ conclusions on World War II experiences,"International cartel agreements were

one of the effective means employed by

the Nazis in preparing forWorld War II," theclassified report said. "Such agreementswere used not only to develop the Nazimilitary potential and to weaken the pre-paredness position of Germany's potentialenemies, but also to provide a screen forespionage activities."

These cartel agreements were enteredinto by various corporations in order toprotect profits by dividing up sales terri-tories among them and to swap patentedinformation. "Loyalty to such agreementsis usually supranational and, consequent-ly, exceedingly dangerous to national se-curity," the report noted.

These business agreements amongcorporations "perform the functions of aninternationalgovernment," the reportsaid."International security demands the adop-tion of an international cartel conventiondesigned to eliminate all restrictive mea-sures imposed by internationalcartels andthecreation of such internationalagenciesas may be essential to the implementationof the convention."

No meaningful controls were everplaced on multinational corporations. To-day, among the few congressional aideswho have interested themselves in theseproblems thereare twoschools of thought.There are those whose idealism has beenshocked by what they view as the inevita-ble threat to America by international cor-porations. They talk in hushed tones of leg-islation which would force these giant

firms to sell their foreign holdings. Whilethey talk about such a proposal, however,they are notoptimistic about itssuccess inCongress because they feel the case forsuch drastic economic action has notbeen made with sufficient force and dramato sway public opinion and votes,

Other congressional opinion favors lesssevere restrictions. Some type of monitor-ing system which would require disclo-sure of now-secret holdings and deals is afirst step favored by some on the SenateMultinational Subcommittee. The propo-nentsof this and other proposals to restrictand regulate American multinationals seeAmerican corporate power with some am-bivalence. Intheir view thereare good andbad corporations, The good corporationscan immeasurably aid foreign nations in avariety of ways. Under their suggestedscheme the bad would be weeded out.The catch is how to set up criteria to deter-mine "good" and "bad" corporations.

Implicit in all the arguments is the ideathat America's corporations form an unac-knowledged world empire. Even a few firststeps at regulating the nation's multina-tional giants would have to set some inter-national standards of behavior for Ameri-can companies.

That it has taken this long to even begintentativediscussions about the problem isa measure of corporate power as much asit is an indication of the complexity of theissue. O+--m

91