The Spectacle of the Besieged City- Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941–1944

-

Upload

timothy-chan -

Category

Documents

-

view

28 -

download

3

description

Transcript of The Spectacle of the Besieged City- Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941–1944

The Spectacle of the Besieged City: Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941–1944Author(s): Polina BarskovaSource: Slavic Review, Vol. 69, No. 2 (SUMMER 2010), pp. 327-355Published by:Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25677101 .

Accessed: 17/11/2013 18:43

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserveand extend access to Slavic Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Spectacle of the Besieged City: Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944

Polina Barskova

Acute Oppositions of the Siege Cityscape

In January 1942, Dmitrii Lazarev, a member of Leningrad's technical in

telligentsia, engineer and specialist in optics and camouflage, and con

noisseur of music and theater, wrote in his diary:

Though we had put the body of my father-in-law in a cold room, the time had nevertheless come to bury him. Our trip . . . seemed endless. Finally we were at the gates of the morgue?a former woodshed. Opening

. . .

the door, we saw in the moonlight a high pile of corpses, some dressed

any old way, and some wrapped in bed sheets. We began our ascent to the

top of the pile, climbing over frozen and slippery-as-ice stomachs, backs, and heads. Despite the cold, the stench in the shed was overpowering....

We felt a dull indifference to the death of a loved one. The way back was easier. We even stopped for a minute, struck by the unusual beauty of

besieged Leningrad in the moonlit night. There was no movement of any sort, no pedestrians at all. The houses with their black shadows looked like a grandiose stage set for some surreal performance.1

What makes this tragic text unusual, what sets it apart from other, at times equally horrific, historical accounts of the twentieth century? It is remarkably common to find in narratives of historical trauma that survivors and witnesses experience "psychological death," temporarily losing sensitivity to pain they can neither digest nor conceptualize in its

immediacy.2 While working on this article, I traveled for a week in July 2008 between Petersburg, the former Leningrad and site of the siege, and

Oswi^cim, Poland, site of the Auschwitz death camp, where some of the most massive "racial" purges of the Nazi genocide took place. This geo graphical "transfer" helped to sharpen the focus of this project, which is to assess how individuals subjected to historical catastrophe relate to their

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers of Slavic Review and Mark D. Steinberg for

their perceptive suggestions, Avram Brown and Jane Hedges for their merciless yet subtle

editing, and the Petersburg scholars of the siege, Iurii and Sophiia Kolosov, Vera Lovia

gina, Olga Prutt, and Boris Firsov, for their generous help and inspiration. 1. D. N. Lazarev, "Leningrad v blokade: Vyderzhki iz dnevnika," Trudy gosudarstven

nogo muzeia istorii Sankt-Peterburga, no. 5 (2000): 203.

2. This term is suggested by Rimma Neratova in V dni voiny: Semeinaia khronika

(St. Petersburg, 1996), 94. Vitalii Bianki reports that one of his strongest impressions dur

ing a visit to the city in 1942 was that Leningraders would narrate the horrors of the deadly winter smiling. Bianki, "Gorod, kotoryi pokinuli ptitsy," Likholet'e (St. Petersburg, 2005), 172. On emotional numbing as a frequent result of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), see Bessel A. van der Kolk, "The Complexity of Adaptation to Trauma," in Bessel A. van der

Kolk, Alexander C. McFarlane, and Lars Weisaeth, eds., Traumatic Stress: The Effects of Over

whelming Experience on Mind, Body, and Society, 2d ed. (New York, 2007), 183-213. On the translation of the mechanism of psychological trauma into terms of collective cultural con

ceptions, see Neil J. Smelser, "Psychological Trauma and Cultural Trauma," in Jeffrey C.

Alexander et al., eds., Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (Berkeley, 2004), 31-60.

Slavic Review 69, no. 2 (Summer 2010)

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

328 Slavic Review

cultural environment. What if the site of the mass death is not covered with faceless barracks, not separated from the world outside by rows of barbed wire nor fashioned from the rubble of adjacent villages destroyed to provide building materials for the camp? What if it is not completely

without history and meaning for its victims, who have not been brought here from afar and robbed of their identities and cultural roots?3 What if, instead, this site is, like Leningrad, a city of immense historical value and architectural grandeur, a palimpsest consisting of diverse levels of histori

cal, cultural, and personal memory?4 This article investigates the various methods by which siege trauma was suppressed and rechanneled. As I see

it, these methods amounted to a reactivation of the aestheticized past; paradoxically, it was during the gravest period of the city's modern history that its cultural memory became crucial for its inhabitants' psychological and emotional survival.

One of the most shocking elements of Lazarev's account is the para doxical intervention of beauty into the zone of horror, of artifice into the realistic narration of death. Lazarev and his helper pause to observe the unusual beauty of the frozen, empty city. The "unreal" city amazes and touches them, while the very real death of Lazarev's father-in-law does not. Can we understand this gaze as a quest for reaction, for some kind of active dialogue between the agent and the object of the gaze, a dialogue that failed to take place at the improvised morgue? The response to horror

appears to be replaced here by a response to beauty. But what consolation lies in the "stage set"?how can artifice undo or even assuage the effect

produced by a pile of corpses? Or does the pile of corpses become a less real scene if arranged upon an urban stage and illuminated by moonlight?

Human consciousness in the second half of the twentieth century seems to find the juxtaposition of beauty and horror, of aesthetic plea sure and physical suffering, a most crucial and uneasy topic; as Theodor

Adorno so distinctly formulated in his seminal dictum of 1949: "Nach Auschwitz ein Gedicht zu schreiben ist barbarisch." This phrase epito mized "the fear that aesthetic pleasure negates horror, by aestheticizing violence and atrocity, by proposing redemption in the face of outrage, or

by providing consolation in the encounter with beauty."5 Lazarev was only one of the many citizens of besieged Leningrad

struck by the both deeply disconcerting and powerful contrast between the "form" and "content" of Leningrad during the winter of 1941

3. On representations of the German campscapes, see David Mickenberg, Corinne

Granof, and Peter Hayes, eds., The Last Expression: Art and Auschwitz (Evanston, 2003),

24-50, 236, 244, 248; Ziva Amishai-Maisels, Depiction and Interpretation: The Influence of the Holocaust on the Visual Arts (Oxford, 1993), 32-42.

4. I would take issue with Lisa Kirschenbaum's statement that "it is not the city's build

ings and streets that 'tell its past,'" asking instead: to what extent did the buildings and

monuments of Leningrad help Leningraders resist the emotional numbness and amnesia

induced by the historical disaster of the siege? Lisa A. Kirschenbaum, The Legacy of the Siege

of Leningrad, 1941-1995: Myth, Memories, and Monuments (Cambridge, Eng., 2006), 14.

5. Janet Wolff, "The Iconic and the Allusive: The Case for Beauty in Post-Holocaust

Art," in Shelley Hornstein and Florence Jacobowitz, eds., Image and Remembrance: Represen tation and the Holocaust (Bloomington, 2003), 165.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 329

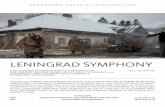

Figure 1. B. P. Svetlitskii, U Sphinksov (By the Sphinxes, 1942). From Nina N.

Papernaia, ed., Podvig veka. Khudozhniki, skul'ptory, arkhitektory, iskusstovovedy v gody Velikoi Otechestvennoi voiny i blokady Leningrada. Vospominaniia. Dnevniki. Pis'ma. Ocherki. Lit. zapisi (Leningrad, 1969), 318.

42.b The aesthetic collision provided by mournful processions making their

way through the city within an architectural "frame" was often expressed in terms of ambiguity. For example, in parallel to Lazarev's account, the architect Boris Svetlitskii executed dozens of works that winter depicting Leningraders dragging corpses on the legendary children's sleds through the vast empty squares, past such architectural landmarks as the Sphinxes, St. Isaak's Cathedral, Gostinyi Dvor, the Bronze Horseman. One's reac tion to Svetlitskii's urban scene might be ambiguous: the "frame" of the

Sphinxes and the embankment both soothes and confuses the viewer,

serving as an overpowering compositional distraction (see figure 1).

6. The account of Sofia Gotkhart, a student in the Russian Literature department of

the Herzen Pedagogical Institute, gives an unexpected twist to the frequent diary topos of

the "siege burial procession in reaction to the cultural environment." She writes: "We put two

children's sleds one behind the other, tied them together, and tied my uncle's body to

this contraption. Our way was long?more than four kilometers along Nevskii Prospect,

Liteinyi Prospect, Sadovaia Street. The day was all frost and sun [ moroz i solntse], everything was sparkling. And the whole way, we saw dead people on sleds." In order to highlight the

shocking contrast, Gotkhart, who attended G. A. Gukovskii's lectures on Russian Romantic

poetry that whole winter, uses Aleksandr Pushkin's celebrated line from "Zimnee utro"

(1829). Dve sud'by v Velikoi Otechestvennoi voine. Sofia Gotkhart. Leningrad. Blokada. Isaak

Kleiman. Riga. Getto. (St. Petersburg, 2006), 63.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

330 Slavic Review

The imbalance between modalities?private internal suffering on the one hand, and the public, external opulence of visual impression on the other?often led citizens to react with rhetorical, open-ended questions regarding the confusing juxtapositions offered by the siege urbanscape. The poet and diarist Vera Inber inquires with frustrated puzzlement: "In this city, in which the ranks of the sick and the dead multiply, / What's the use of these translucent expanses, / The crystal of gardens, the silver of water?"7 At times the citizens' ability to distinguish between the beauti ful and the horrific appears completely distorted; "normal" psychological reactions seem to "freeze" in response to the spectacle of frozen urban death (macabre siege irony turned corpses found under the snow into

snowdrops)* Observers attempt to tame the horror by formulating it as

spectacle: the unpresentable is shielded and therefore tempered by the

terminology of beauty. The actor Fedor Nikitin writes:

At the intersection of Stremiannaia and Marat streets, I was struck by [the following] spectacle. On the pavement lay a rectangle of ice . .. as if carved from the Gulf [of Finland], and inside, a beautiful young woman in a green dress. Her face was not at all deformed; her blue eyes were

open and staring into the distance; her copper red hair had frozen in threads through the ice and become a sort of continuation of her head. This was Ophelia, the ice version. The spectacle was so beautiful that at first you couldn't experience it as tragically horrific.9

The actor's observation closely echoes that of the artist Valentin Kur

dov, who recounts:

I see an American cracker box. Inside the box, I see the frozen body of a small child. In this frost, the baby looks like a cherub with ice-covered

eyelashes. I pause, struck by the strange and inexplicable beauty of this

spectacle. The splendid classical architecture of our city seemed incom

patible with the American cracker box and the child's dead body. I un derstood that I had encountered a super-fantastic reality that no sound

logic could encompass.10

These accounts can be seen as quintessential formulations of the

psychological contradictions engendered by the spectacle of the siege. Here we might ask: between the Kantian sublime that produces pleasure through pain and the Burkean sublime that engenders horror as juxta posed to beauty, which formulation corresponds to the siege spectacle?11 Although traumatized by physical and psychological loss and to some de

7. Vera Inber, "Pulkovskii Meridian," Dusha Leningrada (Leningrad, 1979), 17.

8. Bianki, "Gorod, kotoryi pokinuli ptitsy," 180.

9. Fedor Nikitin, "Blokadnyi dnevnik" (manuscript, museum of siege culture "A muzy ne molchali," School 235, St. Petersburg), 105-6.

10. Valentin Kurdov, Pamiatnye dni i gody (St. Peterburg, 1994), 182-83.

11. Immanuel Kant, Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime [ 1763], trans.

John T. Goldthwait (Berkeley, 1991), 47-48; Edmund Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful [1757] (Oxford, 1990), 36. For an il

luminating discussion of the influence of these theories of the sublime on aesthetics in the

context of the historical upheavals of the twentieth century, see Brett Kaplan, Unwanted

Beauty: Aesthetic Pleasure in Holocaust Representation (Urbana, 2007), 1-18. For useful appli

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 331

gree emotionally disabled, Leningraders still reveled in aesthetic plea sure in response to the beauty of their environment instead of remaining trapped with the notion of horror. Building on one witness's pinpointing of a certain vozvyshennost' (sublime), I propose explicating a siege sublime that does not lie in the distinction between the horrific and the beauti

ful, but rather in the observer's tendency to replace the horrific with the

beautiful, or to reconstruct the horrific as beautiful.12 I suggest that the

siege sublime is thoroughly oxymoronic: instead of creating pronounced distinctions, as both Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant posit, it brings together uncombinable notions and reactions, with the resulting super

imposition usually described as "unreal" or "surreal."13 This study will examine the phenomenon of the siege sublime by way

of the following questions: How did the citizen of besieged Leningrad construe and use urban beauty? What were the possible functions and

meanings of the city's cultural memory during the siege? To what extent did representing the endangered city constitute a strategy of psychological survival and of preserving the site described? Envisioning a siege sublime that operates by filling the lacunae of psychological loss with "anesthetiz

ing" cultural material, this study aims to trace the specific mechanism of such gap-filling.

It is important to note the immediacy of the urge to aestheticize. After the fact, artists often deny, or their audience and critics often deny, the

possibility of and necessity for consolation by means of beauty; but what could be the function of beauty at the very moment of historical pain?

Many diarists insist that the immediacy of their aesthetic response to the siege is paramount: events and impressions appear to risk forfeiting their authenticity if not represented in a timely manner.14 The artist Iaro slav Nikolaev elaborates on this important distinction between depicting the besieged city on the spot and from memory: "Nowadays when artists

try to depict Leningrad as it was during the siege, it is precisely the color that doesn't come across. It comes out wrong. ... I can't quite put my finger on that color, that light. It was sickly, and powerful, and amazingly

cations of theories of the sublime to the discussion of modernity, see Christine Battersby, The Sublime, Terror and Human Difference (London, 2007).

12. Konstantin Fedin, Svidanie s Leningradom (Leningrad, 1945), 14.

13. My formulation of the siege sublime as an aesthetic reaction to the challenge of the unrepresentability of history is informed by, among other sources, the gulag sub

lime that Harriet Murav posits based especially on Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's oeuvre. Murav

claims: "The writer and reader of the Gulag share a similar feeling of individual powerless ness. These conditions and effects, taken together, permit us to see this text as a particu lar form of the sublime. The theme of the unrepresentable in Solzhenitsyn's text serves

to bind individual readers together." Harriet Murav, Russia's Legal Fictions (Ann Arbor,

1998), 188. 14. Nikitin expresses this anxiety with particular poignancy: "My notebook is full; I

managed to put only eight days in it. Still I write, to my own amazement, as if obsessed.

Does any of my writing make sense? Some day all this might be useful as material, a me

ticulous, scrupulous analysis of the air of an irreproducable epoch: everything is forgotten, and the little details evaporate. I write in detail, immediately following events; if I don't

write things down the same day, I find that a lot gets lost forever." Nikitin, "Blokadnyi dnevnik," 138.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

332 Slavic Review

beautiful. Perhaps it came from within, from a different state of being, a

different mode of perception.15 Furthermore, contact with the beauty of the siege urbanscape was

framed and intensified by routines?for example, by daily walks through the lifeless city. Emaciated citizens had to walk many miles at a time: to get

water or food, to get to their place of work or, as in Lazarev's account, to

"bury" their loved ones.16 As a ten-year-old, Iurii Kolosov worked at Smornyi party headquarters

as a courier, carrying important parcels around the city during the siege: "My constant routes through the city gave me ample opportunity to as sess the unique character of the appearance of the siege. It could be ex

plained by the huge masses of snow that nobody would clear away, which

produced an eerie lighting effect, and by the scarcity of peacetime 'ur ban distractions': ads, slogans, etc. The city looked unusually pristine."17 Kolosov's siege diary is filled with the sketched views of the besieged city that impressed him during that fateful winter (see figure 2). Leningraders

were especially perceptive due to their extreme physical and psychologi cal state; their slow, plodding walks concentrating their attention on their

surroundings: "Hunger greatly sharpened impressionability and visual

memory: whatever one's gaze fell upon?the living and the dead, and the whole beautiful dead city?was committed to memory."18

Rediscovery of urban beauty is a common topos for siege diarists. Some commented on this enthusiastically; for example, the architect Lev irin exclaims: "The sight of Leningrad at war is laconic, simple, and beau tiful. It must be said that during this winter, with all its horrors, people's eyes as if opened; everyone says: how beautiful is our city!

"19 These ecstatic

appreciations of the city, these ways of seeing the city anew echo the im

pression of strengthening kinship with the city that we find, for example, in the diary of Elena Manilla, a young art student during the siege: "I have to cross the whole city to get to the School of Arts. It's very far but I find it interesting: to walk and walk and walk. From now on, the city and I are

connected forever."20

This connection between wartime horrors and a new quality of vision,

15. Iaroslav Nikolaev, "18 ianvaria..." in Nina N. Papernaia, ed., Podvigveka. Khudozh

niki, skul'ptory, arkhitektory, iskusstovovedy v gody Velikoi Otechestvennoi voiny i blokady Lenin

grada. Vospominaniia. Dnevniki. Pis'ma. Ocherki. Lit. zapisi (Leningrad, 1969), 144.

16. Many diarists note the citizens' intensified movement: it is "slow" and "silent,"

yet "epic" in its scale. See Nikitin, "Blokadnyi dnevnik," 89; Georgii Lebedev, "Blokad

nyi dnevnik," 10 April 1942, manuscript, Gosudarstvennyi Russkii muzei, Otdel rukopisei (GRM OR),f. 100, op. 484.

17. Iurii Kolosov, interview, St. Petersburg, 1 July 2008.

18. Neratova, Vdni voiny, 97.

19. Lev Il'in, "Progulki po Leningradu. Iz zapisok professora arkhitektury L'va Alek

sandrovicha H'ina," in Papernaia, ed., Podvigveka, 273.

20. Elena Manilla, "Dnevnik," manuscript, GRM OR, f. 100, op. 570. For additional

information on Martilla and her artistic activity during the siege, see Cynthia Simmons

and Nina Perlina, eds., Writing the Siege of Leningrad: Womens Diaries, Memoirs, and Documen

tary Prose (Pittsburgh, 2002), 177-283; Michael Jones, Leningrad: State of Siege (New York, 2008), 142-73.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 333

Figure 2. Entry from the diary of Iurii Kolosov (5 February 1942). From the

personal archive of Iu. I. Kolosov. Used with permission.

an ability to appreciate anew the allure of the city, engendered the poi gnant notion of ostrota (acuteness/sharpness) often discerned by critically minded observers. "Leningrad now became for me something even greater than it was before?and precisely in its present appearance. It is such an acute landscape that one feels heartache. I would like to paint [napisat'] and reproduce [peredat'] all this destruction, this landscape?its acute and

tragic character."21 The adjective ostryi (acute/sharp) is used in Russian to define levels of intensity, including for both pain and vision. Paradoxically, the urbanscape in the descriptions above can both evoke and ease pain; by stimulating creativity, its beauty can also refresh one's vision.

Another dimension of this acuteness is its frequent use to express the

oxymoronic, conflicted nature of the siege cityscape evident, for example, in the following description by Inber:

3HMa pocKomecTByeT. HeT Komia

Ee BejiHKOJienbHM h me^poTaM.

IlapKeTaMH 3epicajibHoro Topiia CKOBana 3eMJTK>. B rojiyGbie rpoTbi Ilpeo6pa3HJia nepHbie ztBopbi.

AjiMa3bi. BjiecK . . . He#o6pbie /tapbi!

21. Pavel Kondrat'ev, letter to V. F. Matiukh (10 May 1944), in Boris Suris, ed.,

Bol'she, chem vospominan'ia: Pis ma leningradskikh khudozhnikov, 1941-1945 (St. Petersburg, 1993), 388.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

334 Slavic Review

3aicaT cyxyMCKOH po30H po30BeeT . . .

HO JHOTOH He?CHOCTbK) BCe 3TO BeeT.

(Winter is luxuriant. There is no end To its splendors and bounties. It has bound the earth in a parquetry

Of mirrored paneling. It has turned

Backyards into blue grottoes. Diamonds. Glitter. Evil gifts.

Sundown shows pink like a Sukhumi rose, But all of this smacks of ferocious tenderness.)22

The architect Aleksandr Nikol'skii still more concisely, even ironically, ex

posed the paradoxical subtext of besieged Leningrad's beauty?namely, the constant threat hanging over the city?with his playful "slogan":

TyjiflH no 3toh KpacoTe, ho noMHH npaBHjia B <oeHHOH>T<peBorH>.

(Walk amidst this beauty but remember the rules of the air raid siren.)23

One of the central rhetorical devices in descriptions of the experi ence of siege beauty is the establishment of oppositions. The account by Lazarev with which this article opens is not limited to undoing the cen

tral opposition between the twin spectacles of urban death and urban

beauty. This text also produces an impression of rhetorical instability by unbalancing several other binary oppositions: the cramped space of the

morgue contrasts with the emptiness of the city; this beautiful yet lifeless

city seems somehow more animate than its inhabitants, alive or dead, who are virtually bereft of human features?the dead do not look like people, while the living almost fail to feel like people.24

This intense clashing of opposites?to the point that oxymoronic sen

sibility leads to rhetorical confluence?might be interpreted as alerting us to the connection between the discourse of besieged Leningrad and the Petersburg text. According to field-defining articles by Vladimir Topo rov and Iurii Lotman, the Petersburg text functioned as a united para digm of polarities: nature and culture, chaos and order, individual and

state, enlightenment and despotism, future and crisis.25 Toporov states

22. Inber, "Pulkovskii Meridian," 17-18.

23. A. S. Nikol'skii, "Akademik arkhitektury," in Papernaia, ed., Podvigveka, 281.

24. Diarists often remark upon the dehumanization of death in besieged Len

ingrad. "This was such . . . non-human death. They looked like old dry brushwood or

piles of planks?an icy mass frozen together. Nobody was horrified?people just ignored it, and if they did look at it?then without any feeling." Neratova, V dni voiny, 69. As if in grim affirmation of Roman Jacobson's argument in "The Statue in Pushkin's Poetic

Mythology" regarding the instability of the animate/inanimate opposition in The Bronze Horseman, the originating template for the Petersburg text, Iakov Rubanchik subtitles his

drawing: "Everything was dead, except for the sentry lions standing on the front steps with

upturned paws, as if alive." V E. Loviagina, ed., Blokadnyi dnevnik: Zhivopis' i grafika blokad

nogo vremeni (St. Petersburg, 2005), 144.

25. V. N. Toporov, Peterburgskii tekst russkoi literatury: Izbrannye trudy (St. Petersburg, 2003), 7-66; Iu. M. Lotman, "Simvolika Peterburga i problemy semiotiki goroda," in Trudy

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 335

that "the inner meaning of Petersburg is in its antithetic and antinomic

character, which cannot be reduced to any singularity: it puts death itself at the foundation of the new life, as if in redemption, as if to achieve some

higher spiritual level [. . .] the Petersburg text quintessentially expresses life on the edge, over the abyss, at the threshold of death, where the way to salvation might be conceived."26

The paradoxical combination of peril and beauty has lain at the foun dation of the Petersburg text since its inception; it is a text defined by constant conflict and opposition. If we accept that the text of besieged Leningrad and the Petersburg text are interconnected, what are the man ifestations and mechanisms of this kinship?

They Remembered Me: The Influence of the Petersburg Text on Representations of Besieged Leningrad

Already in The Bronze Horseman, that matrix of the Petersburg text, we can see how "opposition governs the description of the city at all levels. . . .

Much of the complexity of the poem lies in the surprising relation between the terms of the opposition as they are established in the Prologue and the value they are given in the narrative."27 After Aleksandr Pushkin, for most of the nineteenth century there seem to have existed two separate, even

opposed, modes of the Petersburg text?positive and negative.28 The

"negative" mode obviously prevailed at least in the urban-oriented works of Nikolai Gogol', Vsevolod Krestovskii, Fedor Dostoevskii, Nikolai Nekra

sov, Vsevolod Garshin, among others. But at the turn of the twentieth

century, these two poles paradoxically recombine. One of the most prom inent instances of convergence of the two modes of the Petersburg text

was Aleksandr Benois's manifesto "Zhivopisnyi Peterburg" (Picturesque Petersburg). For Benois, the unique charm of the city lies in the fact that it can be deadly and dying, terrifying and beautiful at the same time: "Look at the physiognomy of the city?and Petersburg will strike you as horrid, merciless, but also beautiful and charming.

... It is a stone co lossus of sorts?monstrous and fascinating. Its cold, terrible gaze always attracts you."29 A locus "of melancholic and sickly beauty," Petersburg can

only be saved if artists "fall in love anew with this city, thus saving it from the peril of barbaric perversion."30 Benois declares that the "real" Peters

burg is the Petersburg of its conception?empty, somewhat dangerous,

po znakovym sistemam, vol. 18, Semiotika goroda i gorodskoi kul'tury. Peterburg, ed. M. L. Gas

parovetal. (Tartu, 1984), 30-77.

26. Toporov, Peterburgskii tekst, 6, 29.

27. Andrew Kahn, PushkinsThe Bronze Horseman (London, 1998), 96-97.

28. For a compelling and original discussion of the "negative side" of the Peters

burg text, see K. G. Isupov, "Dialog stolits v istoricheskom dvizhenii," in K. G. Isupov, ed., Moskva-Peterburg, pro et contra: Dialog kul'tur v istorii natsionaVnogo samosoznaniia

(St. Petersburg, 2000), 6-81.

29. Aleksandr Benois, "Zhivopisnyi Peterburg," Mir iskusstva, no. 1 (1902): 2-4. 30. Ibid., 4.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

336 Slavic Review

and transgressively attractive. Modernity brings this city unnatural vivacity and endangers its true nature.31

The turmoil of post-October Petersburg was experienced by many as a realization of the paradoxical metaphor of urban beauty intensified by peril.32 A rich array of representational strategies emerged in response to this reactivation of the eschatological mythology of Petersburg; as Lisa A.

Kirschenbaum puts it, "the ghosts of the blockade inhabited an already haunted landscape."33 The aesthetic experience of the first siege of the

city (by the army of General Nikolai Iudenich in 1919-20) acquires a new

urgency during the second. For the present study it is especially impor tant that the second siege uses the first as a template in addressing the

Petersburg text.34 The result is a discursive bridging: discourse regarding the end of Petersburg, that aspect of the Petersburg text that proved most

productive in the twentieth century, skips from the first to the second

siege, almost ignoring the 1930s, when, after mass purges of the intelli

gentsia and a population shift to the industrial outskirts, the city became

effectively "provincialized."35 This aesthetic bridging was possible thanks not least to certain cultural

figures who provided the "connective tissue" between the epochs; one of the hardiest and most active of these was Ol'ga Ostroumova-Lebedeva

(1871-1955). During the winter of 1941-42, she managed not only to

31. The beautiful, dying city of the past endangered by the aggressive, unscrupulous

present is a crucial concept in the problem of the symbolist city. See Sharon Hirsh, "The

Ideal City, the Dead City," Symbolism and Modern Urban Society (Cambridge, Eng., 2004), 257-77, 322-25.

32. For analyses of the representational spectrum of "death of Petersburg" discourse, see E. Yudina, "Metropolis to Necropolis: The St. Petersburg Myth and Its Cultural Exten

sion in the 1910s and 1920s" (PhD diss., University of Southern California, 1999); Grigorii

Kaganov, Sankt-Peterburg: Obrazy prostranstva (St. Petersburg, 2004), 177-79; Helena Gos

cilo, "Unsaintly Petersburg? Visions and Visuals," in Helena Goscilo and Stephen M. Nor

ris, eds., Preserving Petersburg: History, Memory, Nostalgia (Bloomington, 2008), 57-88; and

Polina Barskova, "Piranesi in Petrograd: Sources, Strategies, and Dilemmas in Modernist

Depictions of the Ruins (1918-1921)," Slavic Review 65, no. 4 (Winter 2006): 694-712.

33. Kirschenbaum, Legacy of the Siege of Leningrad, 15.

34. Scholars have paid increasing attention to the intriguing problem of the "recy

cling" of the experience of the first siege by the second; see, e.g., Aileen G. Rambow, "The

Siege of Leningrad: Wartime Literature and Ideological Change," in Robert W. Thurston

and Bernd Bonwetsch, eds., The Peoples War: Responses to World War II in the Soviet Union

(Urbana, 2000), 154-70; Kirschenbaum, Legacy of the Siege of Leningrad, 27-29. 35. Viktor Shklovskii, one of the sharpest and most compassionate observers of Pe

tersburg spatiality in the twentieth century, notes in the 1920s: "Petersburg crawls to the

outskirts and becomes a bagel-city with a beautiful but dead center." Shklovskii, "60 dnei

bez sluzhby," Novyi LEF, 1927, no. 6: 18. During the siege, he registers the opposite move

ment: "The city was taken in such a tight circle that it lost its outskirts." Viktor Shklovskii, Tetiva: O neskhodstve skhodnogo (Moscow, 1970), 40. Shklovskii, who always had an eye for

paradox, notes that while the 1930s saw the city's historical memory suppressed and re

placed with new Soviet content, the siege again brought to light the city's historical center

as well as its discursive centrality. This problem is discussed aptly by Cynthia Simmons,

"Leningrad Culture under Siege (1941-1944)," in Goscilo and Norris, eds., Preserving Pe

tersburg, 164-82. For a comprehensive and illuminating study of the fading of artistic di

versity in 1930s Leningrad, consult M. S. Kagan, Istoriia kul'tury Peterburga (St. Petersburg, 2008), 275-89.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 337

survive?many of her peers, including Pavel Shillingovskii, Ivan Bilibin, and Nikolai Tyrsa, did not?but also to become a champion of the Mir iskusstva movement in Leningrad. Boris Zagurskii, director of the Lenin

grad Conservatory of Music during the siege, writes: "I spent some time with Ostroumova-Lebedeva. She read us her diaries. The epoch comes alive [ozhivaet] in them. The personal portraits are remarkable. In gen eral, these notes are very interesting?they should be published."36 The

expression "to come alive" is used very rarely by Leningrad diarists in the winter of 1941-42, and it is even more revealing to see it applied to a cul tural epoch seemingly buried alive by the Soviet cultural authorities de cades before. City ideologists found Ostroumova-Lebedeva's memories, as well as her skills, quite useful in 1941-42, when Leningrad was on the

verge of extinction. In response to salutations from the women of Scot

land, she was engaged by the Smornyi party headquarters to compile a decorative art book about besieged Leningrad. As the artist herself writes, not without surprise: "They remembered me [vspomnili obo mne]"37 In

deed, this was a fortunate occasion for the oldest surviving representative of Mir iskusstva in the city. Ostroumova-Lebedeva's work for this project secured her worker's ration and saved her life. The art book itself was a

conceptually peculiar piece. Ostroumova-Lebedeva explains:

Members of our government decided to reciprocate the art book made

by the Scottish women with one of our own.... Twenty of my lithographs were chosen for this purpose, as well as some photographs. The frontis

piece featured the figure of [Vladimir] Lenin. The book came out very beautiful. Cloth bound with old-fashioned embroidery, the book was put in a box lined with silver and gold brocade. It took four days to produce the book, but we worked from 7:30 a.m. until midnight.38

Many features of this art book seem to be mutually exclusive: intended to allude to and protest against the horrific actuality of war, this art object first and foremost beautifies (through its precious gold brocade, and its

representational devices of the past) the disaster-stricken city enveloping it. While its visual narrative opens with the figure of Lenin, thus affirming the political underpinnings of the eponymous city, the vast majority of the

etchings inside have nothing to do with Soviet Leningrad. Ostroumova Lebedeva recreates here her visions from the Mir iskusstva period as well as her illustrations for the art book Petersburg (1922) executed together with Mstislav Dobuzhinskii and for Nikolai Antsiferov's Dusha Peterburga (1922). Ostroumova-Lebedeva challenges the city's present situation

through negation?we see no bombed buildings, no dead citizens in the

streets, no hint of military propaganda. The artist offers the same inter

36. Boris Zagurskii, Iskusstvo surovykh let (Leningrad, 1970), 85. The manuscript was

indeed published, but only in 1974 and in such form as demonstrated the editors' censoring zeal. See Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva, Avtobiograficheskie zapiski (Moscow, 1974). The origi nal manuscript is held at the Rossiiskaia natsional'naia biblioteka, Otdel rukopisei, f. 1015.

37. Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva, "Dnevnik," in Suris, ed., Bol'she, chem vospominan'ia, 43.

38. Ibid., 44.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

338 Slavic Review

pretation of Petersburg imperiled that she had formulated when the cen

tury opened: in awe we face the serenity of vast, deserted, lifeless squares piled high with snow. Ostroumova-Lebedeva insists on nondiscrimination of historical epochs: her Petersburg-Petrograd-Leningrad is always empty and pristine.39 This conception coincides with Toporov's idea that the "Pe

tersburg text conceptualizes itself diachronically rather than synchronic ally."40 Indeed, for a certain category of Petersburg-Petrograd-Leningrad culture interpreters, the city's defining connection is to its past rather than to its present or future. Ostroumova-Lebedeva was one such inter

preter: for her, Petersburg, filled with aesthetic contradictions as outlined in Benois's article, did not cease to exist with the advent of Soviet Len

ingrad; she sought ways to assert its continuity within the new cultural

epoch.41 One of the preconditions for such manipulations was a poignant relativity and flexibility vis-a-vis the notion of time in besieged Leningrad. The experience of siege time was highly individualized, with aberrations

generally symbolic of psychological self-defense. Inber astutely remarks

upon this phenomenon:

Our street clocks have symbolic meaning. When the shelling and bomb

ing started, they were among the first things to suffer. Clocks showed different times in different parts of town. . . . This was the hour of their downfall. Some completely collapsed; others teetered like weathervanes; still others looked unharmed, but were dead. Time had run out, been exhausted. I'll never forget how once, on a

grim, freezing evening, as a

siren wailed, I glanced up at one of the street clocks and, instead of its dial, I saw a black circle of night sky with bright, hostile stars.42

Inber portrays siege time as dysfunctional, frozen, dead, and yet not ho

mogenous.43 This time can be manipulated in various ways, for example, replaced with an aestheticized urban space by framing space within an

empty clock, or projected onto a different historical moment. Understand

ably, most citizens projected themselves into the future, into the "beautiful

postwar period," while others used imaginary "pasts" as their survival strat

egy and creative template.44 Ostroumova-Lebedeva connects various es

39. For a comprehensive summary of Ostroumova-Lebedeva's oeuvre, see M. F.

Kiselev, GrafikaA. P. Ostroumovoi-Lebedevoi: Graviura i akvarel' (Moscow, 1984). 40. Toporov, Peterburgskii tekst, 26, 35.

41. For discussion of Ostroumova-Lebedeva as participant of the preservationist cre

ation of the "static urbanscape" of Petersburg, see Katerina Clark, Petersburg: Crucible of Cultural Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 1995), 61.

42. Vera Inber, Pochti trigoda: Leningradskii dnevnik (Moscow, 1968), 279. 43. Diarists connect the siege's "frozen time" with its "frozen space." Vsevolod Vish

nevsky observes: "The frozen, quiet Neva. Quiet factory chimneys. On the nearest post we saw a poster: 'Great Festivities?22 June 1941' ... As if time had frozen! We wanted

to take the poster, but it had frozen to the post. Houses were empty, windows broken. . . .

I constantly felt that everything had gone numb, that the landscape was dead." Vsevolod

Vishnevskii, Leningrad: Dnevniki voennykh let (Moscow, 2002), 90.

44. N. V. Lazareva, "Blokada," Trudy gosudarstvennogo muzeia istorii Sankt-Peterburga, no. 5 (2000): 236. Tat'iana Glebova's diary provides a remarkable example of the past

soothing the pain of the present: "Yesterday the air raid siren was on almost all night. . . .

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 339

chatological expressions of the Petersburg text, aiming first and foremost to preserve the urban past: while marking crises, she implies continuity and a seamlessness of this text, hence subverting its Soviet component.

Commenting upon the timeliness of the emergence of Ostroumova Lebedeva's memoirs, Zagurskii notes peculiar contradictions in the im

age of the artist herself: "It's hard to imagine that all this was written and, most important, experienced, by the old woman sitting before us in an old

woman's dress, with an old woman's wrinkled face that features, however,

remarkably clever, insightful eyes with a hidden sadness."45 For Zagur skii, this fragile old lady obviously belongs to the past, but her eyes are

sharp, and vision renders her a crucial agent of the present. Ostroumova Lebedeva stands as a living embodiment of the idea of overwriting and

transcending time. In addition to the symbolic value of her presence in the

city, Ostroumova-Lebedeva bridged epochs in practical terms by tirelessly popularizing the Mir iskusstva movement; and her aesthetic propaganda proved successful, influencing new generations of Leningrad artists.46

For example, one young artist, S. Smirnov-Kordobskii, wrote in a let ter following his visit to the besieged city: "It's hard to convey the feeling you get walking the streets of this city so bound up with all that is remark able in our art and painting. The city streets are empty, but to me, the

landscape is not dead: I feel the breathing and language of the city, at

times like the voice of Ostroumova-Lebedeva, at others like that of Do

buzhinskii, Iaremich, or Grinberg."47 According to this account, the city in

peril could be experienced as alive due to the representational tradition

In order to fall asleep, I lull myself with cozy stories about how someone and I (the way we are, modern people) are somewhere out in the boondocks traveling by relay in a post

carriage, in the time of Pushkin; we have dinner at an inn in front of a roaring fireplace in the company of people of that era, and it's terribly interesting to examine them up close." Tat'iana Glebova, "Risovat' kak letopisets: Stranitsy blokadnogo dnevnika," Iskusstvo

Leningrada, 1990, no. 1: 30. Another interesting example of rhetorical "consolation via the

past" during the siege is the book of memoirs by Vladimir Konashevich, O sebe i o svoem dele

(Moscow, 1968), in which the author interweaves two contrasting narratives?his "idyllic"

prerevolutionary childhood and the siege winter.

45. Zagurskii, Iskusstvo surovykh let, 86.

46. The art historian Petr Kornilov recalls how Ostroumova-Lebedeva would, in the winters of 1941-44, share with visitors copies of Mir iskusstva as a most precious gift. P. E.

Kornilov, "My byli vmeste," in Papernaia, ed., Podvigveka, 119. Ostroumova-Lebedeva's

creative work during the siege made possible an open and eulogistic discussion of Mir

iskusstva in the press of the time; see P. Kornilov, "Po masterskim leningradskikh khu

dozhnikov: Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva," Leningrad, no. 7 (1943): 8-9. Kornilov writes:

"What people surrounded Ostroumova! She is especially proud to have belonged to the Mir

iskusstva group." In the same article, dedicated to the fiftieth anniversary of Ostroumova

Lebedeva's career, Kornilov mentions that though during the siege the artist "ran out of

drying oil, she still uses the same set of gravers she has always used," thus emphasizing that unity of content is inalienable from formal unity. Ostroumova-Lebedeva's view of the

city became emblematic and decisively influenced such siege artists as V. Morozov and N. Pavlov.

47. S. Smirnov-Kordobskii, "Pis'ma," in Suris, ed., Bol'she, chem vospominan'ia, 340.

The artists Stepan Iaremich (1869-1939) and Vladimir Grinberg (1897-1942) mentioned here strongly influenced the tradition of the Petersburg urbanscape.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

340 Slavic Review

of the cityscape as practiced by the "Petersburg art school." The emptiness of the city?so much of its population dead or evacuated?was dually re

interpreted: on the one hand, this emptiness eerily fulfilled eschatological prophecy; on the other, it was in keeping with the genre of the architectural

sketch, which requires people only as staffage figures. As Viktor Shklovskii

aptly notes in the siege section of his book Tetiva: O neskhodstve skhodnogo: "The city is alive and dead."48 Shklovskii appreciated the tragic paradox of

siege representation: the dead body of the city gives birth to new creative

paradigms of urban knowledge and self-identification. The cityscape of the suffering city, insofar as it could be experienced and described in the

representational language of the previous tradition, was alive. Russian Museum curator P. E. Kornilov, who frequently visited

Ostroumova-Lebedeva during the siege, recalls that "she did not want to

depict destruction, but rather to show the city as it was before the war."49 More precisely, not just before this particular war, but before all the cata

clysms of the twentieth century. An analogous "bridging," addressing past crises to meet the aesthetic needs of the present, takes place in represen tations of the besieged city by Pavel Shillingovskii (1881-1942).50 Ostrou

mova-Lebedeva and Shillingovskii shared common artistic views and had a warm collegial relationship; during the worst days of the siege, she would send him lithographic materials.51 But while Ostroumova-Lebedeva's con

tinuity is that of an ever-doomed, yet wholesome and eerily "picture per fect" city, Shillingovskii's continuity is that of destruction (see figure 3) ,52

In 1942, Shillingovskii addressed the city in his work for the first time since his 1923 series Ruins and Resurrection of Petersburg. Between 1923 and 1941, Shillingovskii depicted various Soviet locales?the Crimea, Tatarstan, Moldavia, and Moscow?but rarely his native city. There is a certain oddity in this: once a star pupil of the Petersburg Academy of Art, where tradition dictated constantly using this ultimate art-engendering city as a model, Shillingovskii was interested in depicting only the criti cal stages of his city's existence. For him, ruin and crisis were the most

historically?and rhetorically?suitable state for the city of Petersburg.

48. Shklovskii, Tetiva, 42.

49. Kornilov, "My byli vmeste," 117.

50. For a chronological summary of Shillingovskii's career, see E. V. Grishina, P. A.

Shillingovskii (Leningrad, 1980). 51. Kornilov, "My byli vmeste," 121.

52. Curiously, though in her artworks Ostroumova-Lebedeva asserted timeless

peacefulness, in her diary of that time she allowed herself to indulge in the imagery of

apocalyptic destruction: "I would paint this picture thus: clouds of stinking black smoke

have obscured the whole earth and sky. And tongues of fire, with sparks and steam, break

through and dance about. And below people swarm about." O. Ostroumova-Lebedeva,

"Diary of Anna Petrovna Ostroumova-Lebedeva, artist," in Simmons and Perlina, eds.,

Writing the Siege of Leningrad, 31.

Shillingovskii's interpretation of the eschatological continuity of the meaning of Pe

tersburg during the siege was not unique. Lebedev writes in his diary: "Now as never before

I can hear Jeremiah's curse: 'For this city has been to Me a provocation of My anger and

My fury from the day that they built it, even to this day!'" Lebedev, "Blokadnyi dnevnik," 10 April 1942.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 341

Figure 3. P. Shillingovskii, Osazhdennyi gorod (The Besieged City, 1942). From I. A. Brodskii et al., eds., Khudozhniki goroda-fronta (Leningrad, 1973), 83.

Both Ostroumova-Lebedeva and Shillingovskii create a unified text of the

suffering Petersburg that subverts "real" history (due to an almost com

plete lack of interest in the "Leningrad" period) by imposing connections between the critical stages of urban life.

Shillingovskii's depiction of ruin is polysemantic: its direct task is to bear mournful witness to destruction, but the artist also always insists on his own cocreation of history by means of creative interpretation, invari

ably including in his images a building untouched by war placed next to a ruined one, as if to affirm hope for the city's reconstruction.53 This immanent feature allows for the complex ideological message of Shillin

govskii's cityscapes: his Piranesi-like ruins both remind the viewer of the connection to the city's past and erect bridges to a hopeful future.54 They also convey antiwar sentiment and even an uneasy fascination with the

spectacle of danger. Within the end of the end-of-Petersburg discourse, both Ostroumova

Lebedeva's and Shillingovskii's urbanscapes operate like eschatological fiction. Ostroumova-Lebedeva's city negates destruction and hence ne

gates historical change; Shillingovskii's city is inextricably linked with destruction?two seemingly polar-opposite interpretations of the seam lessness of the Petersburg text that follow two "vectors" of the Bronze

Horseman, whereby odic acceptance and tragic negation of the myth and

meaning of Petersburg acquire a symbiotic nature.

53. Kaganov, Sankt-Peterburg, 194-95.

54. Piranesi and his fictions of urban and historical decay held a strong fascination for the lithographers associated with Mir iskusstva. See, for instance, Betsy F. Moeller

Sally, "No Exit: Piranesi, Dore, and the Transformation of the Petersburg Myth in Mstislav Dobuzhinskii's Urban Dreams,'" Russian Review 57, no. 4 (October 1998): 539-67.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

342 Slavic Review

Recasting the Bronze Horseman

The 240th anniversary (May 1943) of the city's founding did not pass un noticed in besieged Leningrad. Given the scarcity of resources, celebra tions were limited in scale, but every effort was made to highlight the fact that the city's life and history had not been extinguished. Several com

memorative publications focused on the strategies for including the city's past in the difficult narrative of its present.

One complete issue of the journal Leningradw&s dedicated to the fes tive date. Such prominent and officially "approved" chroniclers of the

besieged city as Vsevolod Vishnevskii, Nikolai Tikhonov, and Mikhail Du din submitted articles glorifying the "fortress-city."55 As during Grigorii Zinov'ev's era of "Petrogradocentrism" fifteen years earlier, rhetoric fo cused on the unique qualities of the city and its history:56 Boris Likharev's

poem "Leningrad" eulogizes the city as "the firstling of the people's glory from Peter's days to our time," "symbol of victory" and "happiness of Rus sia."57 Interwoven with such exalted reiteration of the city's present signifi cance were affirmations of its past glory. Vsevolod Vishnevskii writes:

It is called Leningrad. When its first buildings were erected, it was called

Petersburg. Later it was renamed Petrograd. This city has had many names, and it has been witness to many events. And these were no or

dinary events; they were crucial for the fate of the Russian state. This was and is an extraordinary city. . . . Two hundred forty years ago, Peter chose this place for his city: "The city will be founded here!" On an is land amidst the broad Neva, bastions arose. The echo of a cannonade declared to all Russia that a new page of its history had been turned; in

1917, from these same bastions, a new cannonade declared to the world that a new page in world history had been turned.58

Eulogistic framing, an emphasis on heroic origins, a tragic present in terwoven into the epic past: it is difficult not to notice the correlation between Leningrad's 240th anniversary narrative and Pushkin's The Bronze Horseman?the obvious template of choice for the creators of siege mythology.

The monument and its seminal poetic reflection emerge in this is

55. Leningrad, no. 7 (1943). 56. During the period of the so-called Petrograd party opposition, Zinov'ev declared:

"Petrograd has its unique features: it is a more proletarian city than Moscow; quite possibly, the reason for the city's present crisis lies in that enormous effort with which Petrograd

would always throw itself first into battle. . . . We think it wrong to treat Petrograd from a

simplistic, egalitarian point of view. All of Soviet Russia needs Petrograd. Russia does not

need Petrograd to be just another provincial town; Russia needs Petrograd as it is, as the

largest proletarian center in the whole Republic. We see two prospects for the future of

Petrograd. The first is that the Republic leaves the city alone. Petrograd could be treated as

a revolutionary relic. This would doom the city to a slow death. The second prospect is that

the Republic, despite the grave situation, should deem the reconstruction of Petrograd its

most important goal." G. Zinov'ev, "Vstuplenie," in G. Tsyperovich, Budushchee Petrograda

(Petrograd, 1922), 2-3. 57. Boris Likharev, "Leningrad," Leningrad, no. 7 (1943): 4.

58. Vsevolod Vishnevskii, "Ego zovut Leningrad," Leningrad, no. 7 (1943): 4.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 343

Figure 4. A. Ostroumova-Lebedeva, Mednyi vsadnik (The Bronze Horseman, 1942). From N. Sinitsyn, Graviury Ostroumovoi-Lebedevoi (Moscow, 1964), 126.

sue of Leningrad in all possible reincarnations: Dudin offers a modernized

poetic version of Pushkin's text; in an editorial, Vishnevskii explicates the

ideological significance of the monument; Kamenskii describes the history of its creation; Ostroumova-Lebedeva supplies lithographic depictions of it (see figure 4).59 In these texts, the monument, its myth, and its literary reflection appear as symbolic systems that are both completely suited to the moment and completely flexible. Following the literary reincarnations

"organized" by Pushkin and Andrei Belyi, Falconet's Peter again "awakens"

during the siege in Dudin's poem: "You didn't arise merely as a copper mold

by Falconet?you are indeed alive!" Dudin's Peter serves a rather straight forward purpose?to remind Russian soldiers of the victorious traditions to which they are heir ("comrade, we are the offspring of Peter the Great") and of "his" city they are called to defend. In this poem, Peter's time and the siege coexist in a kind of montage-like superimposition of disparate epochs. This device is pervasive in this issue of the journal?for example, Vishnevskii's refrain repeats: "As it was then, so it remains now."60

59. Characteristically, Ostroumova-Lebedeva depicts the Bronze Horseman without the defensive scaffolding built for it in the autumn of 1941, despite having observed the construction thereof that August. From her description of reworking an earlier sketch we can see that this affirmation of continuity gives her strength: "I worked ecstatically, as if intoxicated. My strength is diminished, my heart isn't working properly, and my hand shakes. But as soon as I took up my instrument, I felt my old confidence right away; the first

print calmed me down." Ostroumova-Lebedeva, Avtobiograficheskie zapiski (St. Petersburg, 2003), 3:296.

60. Mikhail Dudin, "Petr," and Vishnevskij "Ego zovut Leningrad," Leningrad, no. 7

(1943): 5, 4.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

344 Slavic Review

Vladimir Druzhinin's novella "The Bronze Horseman" is marked by the same montage device: a performer, in order to maximize the impact of Pushkin's poem upon Leningraders under siege, changes the order of the text's parts:

Kirsanov recited the first lines of the poem. Preparing for this concert, he had rearranged the poem, so that the introduction had become the

ending.... He began: Over gloomy Petrograd, November breathed its autumnal cold. . . . The listeners immediately responded to the actor with agitated attention, as if Pushkin's poem was not about a forgotten and indiffer ent past, but the present feelings and experience of Leningrad. . . . The

poem sounded like the prophecy of genius.... The poem spoke to them of a pitched battle for the city, the savage cruelty of enemies, the mighty cold of unheated apartments.

. . . And then Kirsanov moved on to the

introduction. Now the poem was narrating the glory of the city, its firm ness in battle: Be glorious, Peters city, and stand, firm as Russia itself! That's how Kirsanov finished his reading. In the words of the great poet, Kir sanov had avowed that the suffering of the citizens of Leningrad was not in vain.61

In Druzhinin's text, the function of The Bronze Horseman is twofold: it is

supposed to serve as a mimetic description of the siege; at the same time, in a re-montaged, "reverse" order, Pushkin's tragedy becomes an uplifting propaganda piece, reassuring the citizens that their "suffering was not in

vain." Indeed, the uses of Pushkin's text during the siege were many. On the one hand, this interpretation of Peter's historical role could be seen as consistent with Iosif Stalin's prewar readings of the matter: Peter, the wise and charismatic leader, showed no mercy to the enemies of Russia.

Literary scholar Boris Reizov states that "Pushkin described the tragic fate of individuals, elemental chaos, the image of the great transformer of our

country, and above all this, the grand idea of the state and the lofty inspi ration of patriotism."62 Many of the contributors to the anniversary issues of Leningrad seemed to agree that the grand idea of the state promulgated by Peter and his successors pushed individual tragedies into the background, overshadowed by affairs of the city-power. This interpretation jibes with the Stalinist creation of the usable past: the 1930s saw the reinvention of Peter the Great as a politically correct ruler, the merciless but wise creator of a better future for hitherto uneasy Russian statehood.63 Peter's

siege-time reincarnation is thus one aspect of Stalinist mythmaking.64 In

this context, the siege reaffirmed Peter's ritual value: symptomatically, the

61. Vladimir Druzhinin, "The Bronze Horseman," Leningrad, no. 17-18 (1943): 16.

62. Boris Reizov, "Literatura v Leningrade," Leningrad, no. 16 (1943): 10-11.

63. For a perceptive discussion of the role of Petrine mythology in Stalin's ideologi cal project, see Kevin M. F. Piatt, "Rehabilitation and Afterimage: Aleksei Tolstoi's Many Returns to Peter the Great," in Kevin M. F. Piatt and David Brandenberger, eds., Epic Revi

sionism: Russian History and Literature as Stalinist Propaganda (Madison, 2006), 47- 69. This

fine article sheds important additional light on the subject of the classic study by Nicholas

Riasanovsky, The Image of Peter the Great in Russian History and Thought (New York, 1985). 64. On the Soviet mythologizing of Leningrad for propaganda purposes, see Steven

Maddox, '"Healing the Wounds': War Commemorations, Myths, and the Restoration of

Leningrad's Imperial Heritage, 1941-1950" (PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2009).

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 345

tsar's grave, renovated in 1942, became a site where soldiers took their oath prior to being deployed to fight for their city.65

Crucial for the present study, however, is the fact that this was not the

only usage of Petrine mythology at the time. While the "red count" Alek sei Tolstoi was finishing his trilogy about the tsar, casting him as a glori ous forerunner of Stalin's politics and policies, Tolstoi's ex-wife, the poet Natal'ia Krandievskaia, who declined an opportunity to leave the city of her cultural heritage, wrote:

3#ecb riyiiiKHHa h OajibKOHeTa B^BOHHe 6ecciviepTeH chjtv3t.

O, naivmTb! BepHbiM tu BepHa. Tboh BO^oeM Ha rug KOJibimeT

3HaMeR~a, JiHiia, HMeHa,

H MpaMOp )KHB, H 6pOH3a ?bIUIHT.

(Here the silhouette of Pushkin and Falconet Is twice immortal.

O memory! You keep faith with the faithful. Banners, faces, names

Undulate at the bottom of your reservoir? And the marble lives, and the bronze breathes.)66

For Krandievskaia, it was not Peter himself, but the Bronze Horseman? not the tsar, but the artistic text he inspired?that ensured the city's im

mortality. Two Petrine mythologies and two conceptions of the continuity of Petersburg's cultural memory thus coexisted within a single historical situation: one, public and state-oriented, the other private and artistic.67

This competition of coexisting pasts within a cultural system is ame nable to Michel Foucault's concept of a heterotopia capable of "juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites" incompatible in and of

themselves; in this case, these are the seemingly related, but aesthetically antonymous, sites of cultural memory's interpretation.68

In 1943, a series of postcards was published to commemorate the city's anniversary: images by Ostroumova-Lebedeva, Nikolai Pavlov, and Vik tor Morozov show celebrated architectural sites.69 Most of these urban

scapes strike us as peculiar because they provide no hint whatsoever of the siege. Instead, we see cathedrals, monuments, and canals as timeless.

65. L. Ronchevskaia, "Dnevnik bez slov," in Papernaia, ed., Podvigveka, 165. 66. Natal'ia Krandievskaia, Grozovyi venok (Moscow, 1985), 93.

67. For the public and state-oriented, see Konstantin Fedin's succinct formulations of the siege version of the Sovietization of Leningrad's "imperial heritage": "Leningrad has

preserved its unity of past and present, the old and eternal city.... [This is] a city endowed since the time of Peter with a remarkably consistent tradition in art, literature, science, and

industry. . . . There is much in our character that would be impossible to understand with

out reference to how that character is manifest in the Petersburg and Leningrad cultural historical framework." Fedin, Svidanie s Leningradom, 15, 53.

68. Michel Foucault, "Des espaces autres" (1967), in English at foucault.info/

documents/heteroTopia/foucault.heteroTopia.en.html (last accessed 1 March 2010). 69. Ostroumova-Lebedeva's productive relationship with the genre of postcard be

gan with her collaboration with the St. Eugenia Society at the very beginning of the twen

tieth century; for details, see Goscilo, "Unsaintly St. Petersburg?" 72-73.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

346 Slavic Review

(This strategy was not unique: another Leningrad anniversary publication of 1943 omitted wartime images, declaring the destruction a "separate and too complicated topic requiring special attention."70) All the sites on the postcards are shown in their prewar condition. On the reverse side

we see the city emblem. We would expect this collection to include the insistent symbols of Soviet Leningrad such as the statue of Lenin on his rust-free armored car at the Finland Station, or the one at Smornyi. In

1943, however, together with these signifiers, select postcards portrayed such symbols of the city as the Bronze Horseman, St. Isaak's Cathedral, the

Exchange building, the Rostral columns, and so on. All these structures, the city's prerevolutionary genii loci, were sup

posed to signify that the beauty of Petersburg architecture is invincible and exists outside history, as if the destruction of war is not "allowed" to leave any trace thereon. Depicted on postcards meant to inform the Big Land, the rest of the country, of Leningrad's resistance, the Bronze Horse man became the emblem of the 240th anniversary?symbolizing at once

the city's military might, its "eternal" beauty, and its seamless history.

Siege Frames: Emptiness and Imagination

Inspired by images of the past and appalled by visions of the present, many artists saw the city during the siege as an "unreal" artifact because of its divergence from the "normal" state of prewar Soviet Leningrad. This

conception was informed by various factors, the most obvious and fre

quently discussed being the energetic measures taken to turn Leningrad into a showcase for propaganda art: "Many of us understood that we were to saturate the city with posters. We would publicize our art by turning the

city into one big exhibit [gorod-vystavka]. Huge panels emerged on the walls of the buildings. This was all the city party committee's idea."71

But beyond the utilitarian necessity of repurposing the city as a propa

ganda exhibit, other interesting attempts were made to interpret the city as a whole as a work of art.72 Aesthetically inclined observers endeavored to frame the city rhetorically, thus turning it into a tableau vivant, as Ol'ga Freidenberg termed it, or, to be perhaps more historically precise, a tab leau mort. Freidenberg describes a dismal episode of citizens attempting to obtain water: "Women and children, men and elderly women drew

70. Leningrad: Arkhitekturno-planirovochnyi obzor, ed. N. Baranov, V Kamensky, et al.

(Leningrad, 1943), 4. 71. V. Raevskaia-Rutkovskaia, "V osazhdennom gorode," in I. A. Brodskii et al., eds.,

Khudozhniki goroda-fronta (Leningrad, 1973), 53. Not everyone in Leningrad, however, was

pleased with the quality of the propaganda art covering the streets of the city. Konashevich

complained: "These streets are nothing but a big smear. It looks like a brown-gray patch work; from afar nobody can say what's going on." Vladimir Konashevich, "Vospominaniia,"

manuscript, GRM OR, f. 76, op. 2.

72. Nikitin was not only fascinated by the unique wartime beauty of his city (fasci nated to the point of frequent reiteration of this viewpoint), but saw it allegorically as the

work of an artist: "We all are taken by this beauty?we didn't see it in peacetime. . . . It's as

if a great impressionist put his rays into this amazing beauty to give it all the hues of color

and light." Nikitin, "Blokadnyi dnevnik," 127.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 347

muddy water with dirty dishes. Around them emerged a slippery field of wet ice. This was a motley tableau vivant, reminiscent of life in Asia some

time around the seventeenth century."73 Vladislav Glinka, a Hermitage scholar and official, recalls the view of

the city in November through the window of a dying colleague's deserted

apartment on the Neva embankment: "Like an illustration for some book on Petrograd, beyond the window the Neva slowly rolled along."74 The window frames a moment from a past life, before 1924, when the city lost its name.

In Freidenberg's and Glinka's accounts, the observer's gaze functions as a frame that rhetorically removes the urban spectacle from the winter of 1941. The entire city is evacuated to a remote time and place. This kind of gaze serves as a protective buffer, both for the site and for the

viewer, recalling the observation that the "function of the frame [these material borders]" is generally: "to isolate and protect the image against encroachment from the surrounding space."75 In accordance with Burke's

understanding of the sublime as an idea pertaining to self-preservation, observers of the siege needed an aestheticized spectacle to preserve both

city and citizen from the horrific reality outside the frame. Expanding upon Burke's elaboration, we might say the siege sublime preserves the

agent of the gaze by enclosing the site of historical horror in an aesthetic "containment zone" of spectacle.

One of the most intent observers of the siege, the writer Leonid Pan

teleev, recalls:

I was on roof duty for the first time and saw the city from seven floors up. I saw it as if anew, as if seeing all its beauty and uniqueness for the first time?the city with its buildings, its Neva, Fontanka, canals all "familiar to the point of tears, to the point of swollen glands." It was all like some ancient relief engraving, with a cartouche in the upper corner. I couldn't take my eyes off this sight. And I had the sudden thought: "Look! Memo rize! Drink it all in! You won't see the likes of this again."76

This account attests to the complex temporality of the siege as spec tacle. The estrangement imposed by historical disaster allows the observer to appreciate his city "as if anew" (kak by zanovo)?a particularly telling "as if," for what has now become poignantly visible is prerevolutionary Petersburg, the city of some "ancient engraving" since hidden under lay ers of Soviet existence.77 For Panteleev, his siege viewpoint reveals a more authentic city: "Yesterday I wrote someone that Leningrad has become

73. O.M.Freidenberg, "Osadacheloveka,"ed.K.Nevel'skii,Minuvshee,no.3 (1977): 25.

74. V. Glinka, "Blokada: Fragmenty vospominanii, napisannykh letom 1979 goda," Zvezda, 2005, no. 7:3-6.

75. Gale L. MacLachan and Ian Reid, Framing and Interpretation (Melbourne, 1994), 22. 76. Leonid Panteleev, Priotkrytaia dver' (Leningrad, 1980), 356-57.

77. My understanding of estrangement as one of the central aesthetic mechanisms of

the siege is informed by Kirill Kobrin, "To Create a Circle and to Break It ('Siege Man's'

World of Rituals)," in Andrei Zorin and Emily Van Buskirk, eds., Lydia Ginzburg's Literary

Identity (Bern, forthcoming); and Emily Van Buskirk [Emili Van Baskirk], "'Samotostrane nie' kak eticheskii i esteticheskii printsip v proze L. Ia. Ginzburg," Novoe literaturnoe obozre

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

348 Slavic Review

more Petersburgian than before (probably because there is less civiliza tion: there are few streetcars . . . and few people on the streets. The moon has replaced electric streetlights."78

Panteleev's perception of revived archaism coincides with one of the central texts of the siege sublime, the "Leningrad Apocalypse" chapter of the epic narrative poem Russian Gods (1949-53), composed in the Vladi

mir prison by the poet Daniil Andreev, who served at the Leningrad front in 1942-43.

Bee H3JiyHeHbH nejioBenecKHx

Cepaeri, 3^ecb Shbiuhxca Koma-to.

CjIHJIHCb b e^hhbih CIUiaB tfJIfl BeHHOCTH

C h^een 3o,zjHero: c 4>Pohtohom, C pe3b6ofi nyryHHOH no 6ajiKOHaM, C BejiHHHeM KapnaTH^. H bot Tenepb, noKpbiTbi CTpynbflMH HeHcrrejiHMoro pacna^a,

Ohh Ka3ajiHCb?HeT, He TpynaMH? Hx njiOTb pa36HTa, jihk pa3pymeH?

Pa3BonjiomaeMbie jxyuin Ha HaC B3HpaJTH c BblUIHHbl.

KaK 6y#TO ropbKOH, ropbKOH My^pocTbio, HaM HenoHHTHbiM, CTpauiHbiM 3HaHbeM

06oraTHjra 3th 3^aHbH

Pa3pyriiHBuiaa hx BofiHa,

(All the emanations of the human Hearts that have ever beaten here

Have merged into a single alloy for eternity With the idea of the architect: with the gable, With the cast-iron fretwork of balconies, With the grandeur of caryatids. And now, covered in the scabs Of incurable disintegration

They seemed?no, not corpses? Their flesh is shattered, their countenance destroyed? Souls excarnate

Gazing upon us from on high. As if the war that had destroyed them Had endowed these buildings With a bitter, bitter wisdom, A terrifying knowledge we could not understand.)79

nie, no. 81 (2006): 261-81, atmagazines.russ.ru/nlo/2006/81/ba24.html (last accessed

1 March 2010). 78. Leonid Panteleev, "V osazhdennom gorode," Sobranie sochinenii (Leningrad,

1972), 3:368. 79. Daniil Andreev, Russkie bogi: Stikhotvoreniia ipoemy (Moscow, 1989), 158-59.

This content downloaded from 151.229.160.33 on Sun, 17 Nov 2013 18:43:00 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Repurposing Cultural Memory in Leningrad, 1941-1944 349

Andreev thus envisions the besieged city as a melding of population and cultural artifacts united and decorporealized by common suffering. In his view, ruination brings new knowledge; thus the city returns to its true Petersburgian self, which is inalienable from its perilous and pro

phetic past. The issues of point of view and framing are treated with unique liquid

ity and breadth in the diaries and memoirs of Leningrad museum staff

(curators, art historians, artists) who evacuated thousands of works of art

during the first months of the siege. These professionals spent the siege looking at empty frames, a reality that could not but influence their imagi nations. The artist and writer Vera Miliutina, one of the main chroniclers of the siege-era Hermitage, observed:

The windows faced Palace Square. After so much rattling, there weren't

any panes left in the window frames. The empty picture frames on the walls and the cords hanging from nails induced a cemetery-like atmo

sphere. This was a dead kingdom . . . the naked, ceremonial beauty of which seemed especially regal, striking one with its stern splendor. Of ten I would walk past the bare panels in the Rembrandt Room. Twilight begins to envelop the hall. The Danae is gone; gone are the trembling hands of the old man leaning over his prodigal son.80

One of the most striking episodes of the Hermitage siege saga con cerns guided tours led by curators?emaciated women?showing empty frames to visitors (usually sailors, who would try to bring technical as sistance and even food to the Hermitage). "Anna Pavlovna Sultan Shakh never used to give guided tours before the war. But during the siege, we would see her in the empty halls of the Hermitage, excitedly and expres

sively telling soldiers and officers . . . about the priceless masterpieces the museum used to have."81

Thus the Hermitage Rembrandts were not completely absent from the museum during the siege. Rather, they were present as discursive re constructions through which the bearers of aesthetic memory resisted the absence of the sign by replacing image with narrative. In another sense, too, the Rembrandts could be said, contrary to Miliutina's mournful ob servation (see figure 5), not to have disappeared completely: rather they

were transferred from their usual place within gilded frames into the sub

jective experience of siege survivors who spent the first winter in the Her

mitage cellars-turned-bomb shelters, where many of the staff members lived and died (forty-six bodies were removed in March) ,82 One of the

80. Vera Miliutina, "Rany Ermitazha," in Papernaia, ed., Podvigveka, 66. For informa

tion on Miliutina, I used an admirably researched monograph of remarkable emotional

depth: Aleksandr Rozanov, ed., Vera Miliutina i o nei (Moscow, 1991). 81. Vladimir Kalinin, "Velikii dukh byl vmesto kryl," in Papernaia, ed., Podvig veka,

48, 57.

82. In the absence of actual objects of art, the frame acquired a new, higher aesthetic status within the museum space. Art historian Mariia Shcherbacheva recalls: "The frames

glimmer with particular brightness against the dark-purple background of the walls. The

rays of the setting sun pour through the ancient lilac windowpanes, creating remarkably