The Sintashta Bow of the Bronze Age of the South Trans-urals, Russia

-

Upload

filiptesar -

Category

Documents

-

view

33 -

download

0

description

Transcript of The Sintashta Bow of the Bronze Age of the South Trans-urals, Russia

Bronze Age Warfare:

Manufacture and

Use of Weaponry

Edited by

Marianne Mödlinger

Marion Uckelmann

Steven Matthews

BAR International Series 2255

2011

Published by Archaeopress Publishers of British Archaeological Reports

Gordon House 276 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7ED

England [email protected] www.archaeopress.com

BAR S2255

Bronze Age Warfare: Manufacture and Use of Weaponry

© Archaeopress and the individual authors 2011

ISBN 978 1 4073 0822 7

Printed in England by Blenheim Colour Ltd

All BAR titles are available from:

Hadrian Books Ltd 122 Banbury Road Oxford

OX2 7BP England www.hadrianbooks.co.uk

The current BAR catalogue with details of all titles in print, prices and means of payment is available free from Hadrian Books or may be downloaded from www.archaeopress.com

175

THE SINTASHTA BOW OF THE BRONZE AGE OF THE SOUTH TRANS-URALS, RUSSIA

Andrey Bersenev, Andrey Epimakhov and Dmitry Zdanovich

ABSTRACT

The Sintashta culture of the South Urals (20th–18th centuries cal BC) stands out from the other Bronze Age cultures of Northern Eurasia due to substantial evidences for advanced war techno-logies. The category of distance weaponry is the most prominent among the finds from a military sphere of life. This work analyses artefacts which are the parts of bow made from horn. The authors propose different variants of reconstructions for strengthening the bow.

KEY WORDS

Bronze Age – Sintashta culture – South Trans-Urals – distance weaponry – strengthened bow

INTRODUCTION

The Sintashta materials have been the subject of intense and often heated debate. This cannot be explained exclusively by their relatively recent discovery and extreme originality; it is rather the fact that their significance goes far beyond re-gional importance. The Sintashta culture played a very important role in the formation of the Srubnaya and Andronovo cultural families of the Late Bronze Age, and the Sintashta people were unique in their attempt to create an early com-plex society in the Eurasian steppe (Koryakova and Epimakhov 2007). The discovery and inve-stigation of the eponymous site of Sintashta came about in the 1970s (Gening et al. 1992), but the awareness of its value occurred only later. After subsequent large-scale excavations of Sintashta settlements and cemeteries, which illuminated the extraordinary characteristics of these sites, scholars began to change their views regarding many questions relating to the archaeology of the Bronze Age. A complete review of the history of the Sintashta culture is given in the introductory article by D. Zdanovich (2002). The sites of the Sintashta culture are dated to the 20th–18th cen-turies cal BC (Hanks et al. 2007).

Due to the wide use of aerial photography and better site recognition, the area of distribution, number, size, and settlement pattern of sites are

now well established. In the Trans-Urals steppe, the systems of closed fortifications are only con-nected to the final period of the Middle Bronze Age (20th–18th centuries BC). The settlements of Sintashta type are concentrated in the northern steppe of the southern Trans-Urals (fig. 1). As a general rule, Trans-Uralian settlements are ac-companied by cemeteries. These compactly loca-ted sites were united under the name of ‘Country of Towns’ given by their principal investigator, G. Zdanovich (Zdanovich and Batanina 2002; Zdanovich and Zdanovich 2002). Some archaeo-logists accepted this term as a sort of metaphor, others commented on it rather vociferously. The burial grounds are known from wider areas, in-cluding Kazakhstan (Logvin 2002) and Cis-Urals (Tkachev 2007). However, settlements have not yet been found in these regions.

Twenty-three fortified settlements have been discovered during the past three decades. Most of them contained between one and four building horizons (Zdanovich and Batanina 2002). Out of the twenty three settlements, seven have been ex-cavated to varying degrees. The best studied are Sintashta, Arkaim, Ustye and Kamennyi Ambar (Ol’gino). Twelve cemeteries are known in the Trans-Urals, but this number cannot be regar-ded as final, because cemeteries are not known for several settlements. Conversely, a few ceme-teries have no visible connection to settlements (Epimakhov 2009). In the Trans-Urals, nine ce-meteries have been excavated (200 burials), in the Pre-Urals six cemeteries (46 burials), and in northern Kazakhstan only one cemetery (28 bu-rials). In the Pre-Urals, the Sintashta burials and kurgans are included in multi-stage cemeteries. Overall, the database of the Sintashta culture is rather rich, but the full extent of its potential has still not been realized.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL REPRESENTATION

Settlements

The settlements are usually located in the central parts of the large river valleys, near a stream or ravine or river mouth. They occupy the spacious flat, dry ground of the first fluvial terrace, yet naturally fortified areas were rarely used. A wa-

Andrey Bersenev, Andrey Epimakhov and Dmitry Zdanovich

176

ter barrier usually separated the cemetery from the settlement. The architecture of the Sintashta settlements is characterized by a closed system of fortifications. Their monumental character and complexity in comparison with other sites are very impressive. The fortification systems are represented by an oval or round shaped plan with radial grouped houses. In some settlements, the traces of reconstructions are recorded both archaeologically and by aerial photography. Despite the monumental character of fortificati-on, real traces of military activity have still not been discovered. The closed fortifications con-sisted of ramparts and ditches, surrounded by a fence or wall. Fortified grounds enclose between 6000 and 20000 m2. The wood and earth buil-ding technique was commonly used. The ram-

part wall could reach 3 to 4 m in height and 4 m in width. In two fortresses, stones were also used on the outside.

The internal space of the settlements is al-most entirely occupied by buildings, organised into sectional blocks. Usually settlements con-sist of two circles of houses of standard dwel-lings, separated by a street and a central square. Generally, the centre of the settlement was free of any buildings. The number of houses, which are usually rectangular or trapezoidal, correlates with the size of a settlement. The house sizes are very similar, usually between 100 and 250 m2. The construction principles are standard with a frame-pillar construction exclusively. The lon-ger longitudinal walls were adjacent to the next house.

Figure 1: Map of the Sintashta culture. – 1 Stepnoe-M cemetery. – 2 Solntze II cemetery. – 3 Kamennyi Ambar-5

cemetery

The Sintashta bow of the Bronze Age of the South-Trans-Urals, Russia

177

All houses had a standard floor plan: an eco-nomic area, a living area, and a small antecham-ber or porch going out to the centre of the settle-ment. The heating system of such a large house was fairly efficient: on three sides, it was iso-lated from the cold by adjacent houses and the defensive wall, and the fireplace in front of the entrance created a form of heat air lock. Every house contained one or several wells next to the remains of a cupola shaped furnace where traces of metallurgy have been recorded. The living space occupied an area of 35–65 m2, which might accommodate 20–30 people (Epimakhov 1996; Grigory‘ev 2002).

The excavated sites yielded mainly everyday material such as animal bones, pottery fragments, spindle whorls and tools for leather working. Yet a fairly large number of finds connected to metal production and metalworking (pestles, abrasives, nozzles, slag, metal drops) is also typical for the Sintashta sites. These traces are usually even-ly distributed on the surface of a dwelling. The metal inventory from the settlements is represen-ted by blade objects demonstrating the decline of traditions of the Circumpontic metallurgical complex and the forming of Eurasian metallur-gical prototypes. These are slightly curved sick-les, knife-daggers, fishhooks, awls, and chisels. Compared to the large number of finds connected to metal production, the number of stone moulds is not large. Special objects or markers of social status are almost completely absent in the settle-ment collections. Therefore, the settlement finds do not reveal socially determined areas nor spe-cialised buildings and blocks.

Cemeteries

The Sintashta cemeteries occupy the flat portion of the first and second river terraces. The num-ber of funeral complexes within one cemetery can vary from five pits to several dozen. Burial grounds are generally found close to the fortified settlements. The only difference between the bu-rial grounds is the degree of their density.

At present, funerary sites are visible as kur-gans. According to some scholars (Grigoriev 2002), the Sintashta burial ground did not have a common mound; each grave was marked by a special construction that took the form of a small hill before being destroyed. The structures above the grave were made of wood and soil; there are no reliable examples of the use of stone, except the ones from the Pre-Urals area. Sacrificial de-posits consisting of parts of animals and pots

were placed into the grave and the floor under the barrow, which constituted the major elements of the funeral area.

The ways of organising the space under the kurgan – number, composition, orientation, and locality of graves with regard to the central grave – vary. About 85 % of multi-grave barrows have a quite clear planning structure. The funeral area was enclosed by a circular ditch (sometimes with a small bank) with entrances or causeways. The largest (3–4 m in length) or double graves usual-ly have the central location. In the Sintashta pe-riod, the graves were oriented North/South. The other structures were situated around the central complex with different degrees of regularity. Therefore, within some barrows a clear contrast can be recognized between the ‘centre’ – more significant – and the ‘periphery’ – of lower sta-tus, but undoubtedly connected with the central grave. Stratigraphic observations confirm the multi-stage character of the mortuary complex formation. It is obvious that some burials were secondary to the primary complex. Alongside such an established pattern some divergence can be observed.

The pit graves differ in size and complexity. They are more or less similar in form: rectangular with a stable length:width ratio (3:2). All grave structures were of wood and earth; stone is very rare. The mortuary chamber was furnished with a wooden frame covered by one, two, or even three ceilings made of logs and straw. The large gra-ves yielded individuals of various gender and age compositions; all ages are represented. No clear markers of social inequality have been discove-red. However, 5 % of all graves contained coup-les: a man and woman lying in a position facing each other. Some of the larger graves contained up to eight individuals. Nevertheless, 52 % of the burials were single individuals, mostly children. The deceased were placed on organic bedding on their left (rarely on the right) side in a contracted position with hands near the face.

One of the most outstanding characteristics of the Sintashta funeral ritual is the abundance and variability of animal sacrifices, chiefly domestic animals: horse, cattle, sheep, and dog. The varia-bility is also expressed in the numerous combi-nations of different animal body parts and where they were located. Whole skeletons obviously cannot be interpreted as funeral food; this is es-pecially true in relation with horse depositions in combination with chariot traces or finds of cheek-pieces. Notable regularities are: a horse usually accompanied a man; children and young women were usually given small horned animals, which

Andrey Bersenev, Andrey Epimakhov and Dmitry Zdanovich

178

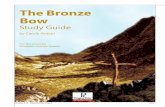

Figure 2: Armament of the Sintashta culture. 1 mace. – 2 battle-axe. – 3 knife?? Chisel?. – 5 spearhead. – 6

cheek-piece. – 4. 7–16. 18–23 – arrowheads. – 17 armour parts. – Provenance: 1. 3. 5–23: Kamennyi Ambar-5

cemetery. – 2. 4: Sintashta cemetery. – Material: 1. 9–16 stone. – 2–5 bronze. – 6 horn. – 7. 8. 17 bone

The Sintashta bow of the Bronze Age of the South-Trans-Urals, Russia

179

being numerous occupied the lowest position in the hierarchy of species of sacrificed animals. The horse was on the top of this hierarchy.

Grave goods are numerous, and the most fre-quent is pottery. Metal goods split into the fol-lowing categories: weaponry – spearheads, axes, knife-daggers, arrowheads, darts; implements – knives, sickles, needles, awls, gouges; orna-ments – pendants for braids, beads, pendants in one and half twists. There are as well many ob-jects made from bone and horn. Above all, the cheek pieces should be noted. The objects made from bone also include arrowheads, small ‘spa-des’, knife handles, and spindle whorls. The set of stone objects consists of numerous arrowheads of two types (tanged or with a truncated base), pestles, ‘anvils’, and abrasive stones. There are no obvious luxury goods.

In some cases, the remains of two-wheeled chariots were found, which were furnished with wheels with 10–12 spokes and an imitation of harnessing for a pair of horses. In general, the wheel traces are recorded in form of two parallel oval-elongated imprints with lens-like sections. They are usually situated 130–160 cm apart from each other. This distance can be regarded as the gauge of a chariot. We would not insist on that the ritual imperatively required placing the whole chariot into the grave (yet, undoubtedly, such ex-amples are well known), but rather similar gauge size supports this hypothesis. These ‘wheel im-prints’ also correlated with a post hole, which is usually located in or near the centre of the gra-ve floor. Such ‘charioteer’s graves’ (14 %) often contained adult males accompanied by numerous weapons. Most of these are collective graves and they were located either in the centre or in the periphery (Epimachov and Korjakova 2004).

The Gender and age of the deceased is reflec-ted in the grave good composition. Weaponry except for knife-daggers (which may have been considered a tool rather than a weapon) are ac-cessories of male burials. Ornaments, awls, and needles are considered female attributes. This differentiation appears to have taken place from about three years of age. Objects interpreted as the markers of social status and social power – maces, spearheads, chariots – are encountered both in central and in peripheral graves.

Hence, the Sintashta funeral ritual is distin-guished by its high variability in comparison with other Bronze Age cultures in the Ural. However, it is not easy to interpret these characteristics. Brilliance and diversity of the Sintashta funeral rite was probably partly conditioned by the ne-cessity to assign a new system of cultural stereo-

types to a society at an early stage of its consoli-dation. The subsequent decrease in the variability of the burial rites demonstrates a standardisation of the ritual framework. Certain ritual elements passed to other forms (for instance from materi-al to verbal ones), or they could remain implicit, and consequently they would not have had spe-cial attention and material realization. This pro-cess can be observed in the Petrovka culture, the ‘daughter-branch’ of the Sintashta culture.

DISTANCE WEAPONRY

This brief review demonstrates that the Sintashta sites possess extensive evidence of advanced war technologies: an enclosed system of settle-ment fortification, chariots and a full set of arma-ments in burials (fig. 2). But evidence of actu-al military activities at the settlements or even injuries on bones on the individuals in the ce-meteries are absent. For instance, only around a dozen of stone and bone arrowheads were found at the Kamennyi Ambar (Ol’gino) settlement. However, the military sphere of life was clearly symbolised in mortuary rites, but the arrowheads have been most frequently placed in burials. The long-distance weaponry is represented by bone or horn parts of the bow. This long-distance wea-ponry is found in one fifth of all burials (46), but these are mainly disturbed (28). These gra-ves contain both individual and collective buri-als. In total, 237 arrowheads and eight parts of bows are known. The typology of arrowheads is based on their material and construction. We di-vided the arrowheads into the following groups: stone (tanged or with flat base), metal (bronze) and bone. The difference in the quantity of ar-rowheads is also high. Morphological groups correlate with the quantity. The first two groups (stone arrowheads) numerically predominate: 48 % the tanged ones, and 38 % the ones with a flat base. In general, the tanged arrowheads are considered as a ‘visiting card’ of the Sintashta warfare, although they were chiefly found in ce-meteries.

The number of arrowheads varies from one to 20 in a closed Sintashta complex. Single ar-rowheads are known from undisturbed graves; i.e. that these items were deliberately placed here in such small quantity. Among the most striking examples is a male burial with a chariot (Krivoe Ozero cemetery) and a female burial from the Sintashta burial ground. Here so-called ‘quiver’ sets of arrowheads represent the special interest. Unfortunately, we have no confirmed evidences

Andrey Bersenev, Andrey Epimakhov and Dmitry Zdanovich

180

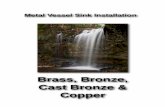

Figure 3: Parts of the Sintashta bow. 1 arrow rest. – 2 clasp or arrow rest? – 4–6 top-ends of the bow limbs.

– Provenance: 1–4 Kamennyi Ambar-5 cemetery. – 5. 6 Stepnoe-M cemetery

for a reconstruction of the quiver assembly. These rare cases allow us, to suggest an arrow of about 60–70 cm in length. Nevertheless, at least 15 ‘qui-ver sets’ are potentially known, but the diversity in the quantity, shape and material of arrowheads within the same ‘quiver’, as in more than half of all cases, challenges any early assumptions.

THE SINTASHTA BOW: MATERIAL PROOF AND CONTEXT

Research on the problem of the steppe zone bow during the Bronze Age is extremely scar-ce (Shishlina 1990; Nelin 1996). D. V. Nelin assumed the knowledge of the strengthened or

The Sintashta bow of the Bronze Age of the South-Trans-Urals, Russia

181

composite bow in the Sintashta population (Nelin 1996, 61). N. I. Shishlina came to the conclusion that two variants existed in the Srubnaya cultu-re – the self bow and composite bow (Shishlina 1990, 32–34). Due to the paucity of reliably at-tributed finds, at the time Shishlina’s proposal could not be evaluated against the archaeological material.

Until recently, research on the design of the Sintashta bow has been lacking. This can be ex-plained firstly by the rarity of finds. This situa-tion changed thanks to the investigation of the Stepnoe cemetery in 2007 (D. Zdanovich and E. Kupriyanova’s excavations) and by the explora-tion of the cemeteries of Solntze II (Epimakhov 1996) and Kamennyi Ambar-5 (Epimakhov 2005).

ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATA

Burial ground Solntze II, kurgan 11, grave pit 1. The pit is of a large size, and has wooden board and siding in the floor (ground) part. In ancient times the grave was ‘robbed’. It appears that such ‘robberies’ in many cases were of ritual character. Notwithstanding, total ‘robbery’ (in the course of which the anthropological remains had been re-moved before they finally lost the soft tissues) the burial preserved numerous animal sacrifices and a number of artefacts at the bottom of the grave: a vessel, a pair of bronze hooks and an ob-ject of elaborate shape suggesting for a bow limb (top-end). This last object is made from horn and the maximum dimensions are 72 x 32 x 27 mm (fig. 4, 3).

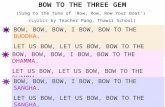

The rectangular (in the plan view) base has a massive S-shaped asymmetrical hook at its re-verse side. This hook has a longitudinal grooved channel apparently to achieve a maximal tight adhesive joint where it is attached to the wooden base. A tenon was used for the same aim. The round profile of the recessed hole was made in the out-shot of the hook. It is very likely that in addition to the discussed methods they were also used to wrap the base and arc of the bow from the outside. The smoothly sharpened end of the hook is lost.

Stepnoe !emetery, kurgan 4, grave pit 13. Tomb 13 is one of the largest on the plateau of the kurgan. The dimensions of the burial cham-ber are 3.15 x 2 m, and the depth is 2.5 m. The ceiling of the chamber was held up by a suppor-ting pole. On the ceiling (1–1.3 m over the pit floor) along its southern wall numerous remains of sacrificial animals were found, including a

whole skeleton of a dog. The pit was ‘robbed’ in antiquity. At the time of the ‘robbery’ the burial chamber was still hollow.

At the bottom of the pit, fragments of two skeletons were discovered in situ (bones of lo-wer limb with adjacent fragments of hip bones). The buried children, both about nine years old, possibly a girl(?) and a boy, were positioned parallel to each other on their left sides, with their heads directed to the northern part of the chamber. Notwithstanding that the grave was ‘robbed’, numerous grave goods were preser-ved: pottery (four vessels with ornaments), a cheek piece with pins, wooden goods with metal clamps, stone implements, 13 arrows with stone, bone and horn heads, animal astragals, silver ad-ornment and also objects of horn, which can be interpreted as parts of bows.

Two items were found in the south-eastern part of the grave. At the feet of the male skeleton near the southern wall of the pit lay a S-shaped, elaborately worked, object with a hook (no. 1; fig. 4, 1). The other artefact, apparently also re-lated to the bow (no. 2; fig. 4, 2) was found at the eastern end of the wall of the pit. It can be attributed as a part on the end of the limb or as a ‘ledge’ like an original ‘backsight’, which was attached to the handle riser section and used as an arrow rest. The distance between these finds is 1.3 m. Both items lay sideways.

The main features and dimensions (70 x 35 x 25–27 mm) of the S-shaped piece from the described burial bear close resemblance to the find from the cemetery of Solntze II. The main distinctions concern the length of the base, ar-rangement of the hook and several other minor characteristics. For example, the rubbing strip is complemented with a small ledge, the end of the hook has a flat cut, and the inner blind hole has rectangular cross-section.

The horn ‘pan’ (40 x 19 x 16 mm) has a rectan-gular base with three transversal arranged salient edges, which form two ‘cavities’. Depending on the method of reconstruction it was used as the arrow rest or as the bow-string notch. The base of the artefact has a longitudinal groove (chan-nel).

Two tips of a bow limb were found in the we-stern half of the same burial. They are made from the endings of elk prongs (fig. 3, 5. 6). These finds lay on the bottom, parallel and close towards one another, with sharp ends (points) directed to the pit wall. In the proximity of these items there were ten arrowheads: seven made of bone and horn, three made of stone. The arrowheads were scattered randomly on the floor of the pit.

Andrey Bersenev, Andrey Epimakhov and Dmitry Zdanovich

182

Figure 4. Parts of the Sintashta bow. – 1. 3. S-shaped hooks, for the upper end of the bow limb. – 2 ledge, which

served as arrow rest (Variant 1) or as string notch (Variant 2). – Provenance: 1. 2 Stepnoe-M cemetery. – 3

Solntze II cemetery

The Sintashta bow of the Bronze Age of the South-Trans-Urals, Russia

183

Characteristics and preservation of the tips of the bow limbs diverge notably. The tips of bow limbs are 118 and 69 mm in length and have a practically identical external diameter of 19–20 mm. The inside of both objects has a dead taper sleeve, however, whereas in the short (no. 2, fig. 3, 5) the bush occupies almost all internal room (55 mm), then in the long one (no. 1, fig. 3, 6) – it hardly exceeds half of the internal room (69 mm). Both artefacts have a full-length perforati-on (6 mm) in the reduced neck portion (thinner part). The larger specimen is complemented with a small side cutting (this part of the second one was ruined in antiquity).

Kamennyi Ambar-5 cemetery, kurgan 2. The excavation of this cemetery contributed informa-tion about the bow construction: in grave pit 2 a ‘pan’ was found, and in grave pit 15 – half-fi-nished tips of bow limbs and a central lath. The first find comes from the central tomb, which is very big, but also a completely robbed burial and human bones, in contrast to numerous traces of animal sacrifices, were not found at all. The small (29 x 19 x 21mm) horn item found there, has a rectangular base with a longitudinal groove and two vertical step-shaped arises from the outside, which form the central channel for the arrow (fig. 3, 1).

The set of objects from pit 15 (the same kur-gan) is much bigger and included a quiver with different-types of arrowheads (fig. 2, 7–16. 18–23), parts of a bow, a knife and four vessels. The grave pit contained an individual burial of a young man and had a number of extraordinary characteristics unlike other burials (Epimakhov 2005): such as many animal sacrifices; an ancient weathered shoulder of a large animal put on the shoulder of the buried person; a fragment of gold-foil near the hand; and an infant burial on top of the ceiling.

For the production of the half-finished tips of bow limbs horn was used, namely the antler tips of elk and saiga, of 136 and 115 mm length (fig. 3, 3. 4). In spite of the heavy polishing of the surface the objects have no traces of use-wear (Usachuk 2005, 187), but this is not surprising in the context of the incompleteness of the overall manufacturing process. Since such examples are well known, one may suggest that imitations of originally used objects were used in funeral rites: similar horn segments were found in other ceme-teries (Solntze II, kurgan 11, burial 2; Kamennyi Ambar-5, kurgan 4, burial 8), as well as with weaponry. Nevertheless, these artefacts can be interpreted in the military sphere only with caution.

The interpretation of a bone plate with two op-posite cuttings (79 x 29 x 6 mm) (fig. 3, 2) is less definite. Its inner surface has a weakly expressed longitudinal groove that suggests an attachment to a cylindrical surface (the handle riser section of a bow?), however, traces of usage (polishing, folding), according to A. N. Usachuk’s conclusi-on (2005), were visible on all surfaces including the cuttings. This fact has allowed Usachuk to of-fer another interpretation of the item: as a clasp. The context of the find does not exclude such a theory.

In our proposal we have introduced a detailed record of the artefacts, which were found in the large tombs (both in individual and collective ones). These graves contained burials of adults of both genders and children. In some cases stone, horn and bone arrowheads were found alongside bow parts and other grave goods. Authentic woo-den bow parts have not yet been discovered and the location of the horn parts does not give clear answers.

RESULTS OF USE-WEAR ANALYSIS

The studied S-shaped objects, notwithstanding their formal resemblance, essentially vary in their manufacturing technology. Thus, workmen used carving to make the artefact from Stepnoe (fig. 4, 1) as main technique of the further shaping of the item. This can be seen from differently lay-ered tracks in the form of linear recessed and protruding grooves. This regularity in the tracks’ combination suggests that the tool used for sha-ping had a small working part (a blade with two sharpened edges) and apparently could have been made of stone, which is confirmed through the ‘wave-like’ bottom of the piece. The main tech-nique of the after-treatment of the corresponding part from the Solntze cemetery (fig. 4, 3) was grinding and probably even polishing, because the surface of the studied item is very smooth. ‘Polishing out’ the surfaces during maintenance can be excluded, since, as far as surface configu-ration is concerned, it is rather elaborate to under-go uniform friction in the entire area.

The second distinctive technological method is the manufacture of a recessed hole for a fi-xing pin. The square (in plan) hole on the top-end piece from the Stepnoe cemetery was made by slotting. We failed to determine if pre-drilling had taken place, as in the bottom of the hole such traces were not detected. Another top-end had a round hole, made with the help of a mounted and flat perforator (borer, drill). Both skilled

Andrey Bersenev, Andrey Epimakhov and Dmitry Zdanovich

184

workmen used all accessible manufacturing me-thods of their time, beginning with the material selection, creating it and finishing with polis-hing the item.

Compared with these elaborated and even ar-tistically manufactured top-ends, the tips of the bow limbs (Stepnoe, fig. 3, 5. 6) look plain, if not ragged. Tool marks were not detected on the outside surfaces of the two studied items and the inner surface of the longitudinal hole for fixing the piece onto the ends of the bow limb also did not show any tool traces.

The ledge (?) from Stepnoe (fig. 4, 2) was made by chiselling with the help of a tool with a metal tip. The traces on one of the guiding groo-ves give evidence of this – they were not com-pletely polished while in use. The hollow on the base is made by scraping. The long longitudinal tracks preserved at the surface of the base very probably did not undergo any finishing touches (shaping or polishing), probably for a tighter connection with the bow arc when glued.

Shock-absorbing traces are most clearly pre-sented on the two top-ends (fig. 4, 1. 3), since here a wearing down (and loss) of parts of the items material is visible. The abrasion of some sections is considerable and sums up to 3–5 mm (!) from a supposed newly-worked piece. Taking into consideration a rather high hardness of the used material, it is possible to presume that functional stress on this structural bow part was enormous. The question of use depends not only on the bow strength, meaning the power of the string on the top-ends, but also on the number of shots made. In the introduced cases, we can talk about thousands of shots. A further interesting observation of the use-wear traces on the hollow of the winding hook of the top-end is a clearly defined direction of abrasion: the first one de-scribed – right, the second one – left. This ap-pears to show evidences for different bow mo-difications: for a left-hander and for a right-han-der. The fact that the top-ends, as structural parts of the bow, were used until ceasing to function, does not contradict this interpretation.

The surfaces of the horn tips of the bow limbs from the cemetery at Stepnoe show no tra-ces of tool working and use-wear. Only insigni-ficant traces, under 1 mm, of wear on the hole rim for the bow string’s end (fig. 3, 6), which drastically differs from the worn down hollow of the hook, for the bow-string’s end, and the chop-py rim of the socket let us suppose a moderate lifetime of this bow part. No definite conclusions can be stated about the second (smaller) ending, due to its poor preservation and some structural

features. The socket of this ending (fig. 3, 5) is so deep that it is cross-cutting the hole for the bow-string’s end and this probably caused da-mage to the ending’s wall. It is highly likely that this tip is not a piece that was used and damaged while in service, but rather a failed attempt to make such a horn part of the bow.

Traces of usage on the ‘ledge’ from Stepnoe (fig. 4, 2) can be clearly seen on the middle and inner parts of the low edge of this piece. A wear-down of up to 0.5–0.8 mm of the walls can be observed, this ostensibly proves a theory of usage of this bow element as an arrow rest during the shooting.

VARIANTS OF RECONSTRUCTIONS

The find-context and traces of use-wear allow reconstructions of two variants of the Sintashta composite bow to be proposed.

Variant 1 (after A. Bersenev and A. Epimakhov)

A conical piece was used as a bottom bushing and string notch (fig. 3, 3–6). It was placed on the end of the lower bow limb and ensured a firm faste-ning of the bow string and also guaranteed the fast substitution of the string in case of breakage. The duality of finds and their location side by side are indirect evidences of this version. The parts whe-re not attached to the limb, when positioned in the grave. The upper limb end was furnished by a S-shaped top-end (fig. 4, 1. 3) which was faste-ned firmly to the wood base. The load on this part was considerable. One more horn element, with a rectangular concave base and cross-located lugs (fig. 3, 1; 4, 2) was positioned on the middle of the handle riser section over the grip. It could be used as arrow rest (or plate) and has the marks of thorough fixation.

Variant 2 (after D. Zdanovich)

The second version has been developed due to the finds from the Stepnoe cemetery. The condi-tions of discovery suggest that fragments of two polytypic bows were found. One was discovered in the western part of the grave and the other on in the eastern part.

Type 1. The distinctive feature is the mounting of tips at both limb ends (fig. 3, 5. 6). Since they were found parallel to each other in the grave, they can be interpreted as the result of deliberate

The Sintashta bow of the Bronze Age of the South-Trans-Urals, Russia

185

destroying of the bow in half. Such a breakage with this kind of weapon is founded on the com-bination of flexible limbs and rigid ends.

Type 2. This reconstruction is characterised by the presence of short laths on the ends of limbs. Thus the parts with cross-located lugs (fig. 4, 2) did not serve as arrow rests as interpreted in Variant 1, but are seen as string notches. The S-shaped element (fig. 4, 1) was placed on the end of the opposite limb. Both artefacts were manufactured in a very similar manner and identical material was used. Despite these argu-ments, the archaeological context of the finds does not suggest they should be interpreted as parts of the same bow.

It is well-known that most of the ancient bow strings were fitted with loops on both ends to ensure better string safety. However, another method of attaching is possible, where one end of the limb is bent and the string is fastened by using a self-tightening knot (Medvedev 1966, 19). The Sintashta bow (type 2) is probably cha-racterized by this method. In this case the lath (fig. 4, 2) served to fasten one end of the string tightly and the S-shape top-end (fig. 4, 1) was used to put the bow in a run position with a de-tached string. Another assumption on the bow morphology of type 2 can be made: the limbs were asymmetric and of different thickness (1.6–1.8 and 2.7 cm). Variant 2 proposes the existence of two well developed strengthened bow types in the Sintashta culture.

CONCLUSION

Summing up our review we can propose that the Sintashta population used a technology to produce and wield a strengthened bow. To the wooden bow limb parts of horn (or bone) were added. Short lengthed arrows (50–65 cm) point indirectly to smaller sized bows, because it im-plies a small brace height. The proposed versi-ons of reconstructions of the strengthened bow do not deny simple variants of bow design as the ‘self bow’. Considerable variation of ma-terials, morphology and the large quantity of arrowheads are indirect arguments for this. The tradition of including a composite bow or parts of it into the grave declined in the post-Sintashta period by degrees. Uralian and Siberian bows of later periods differ from the Sintashta types significantly (Solov’ev 2003, 34. 42). It is pos-sible to say, that several independent traditions of bow making in North Eurasia can be identi-fied.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Epimakhov, A. V. 1996. Kurgannyi mogil’nik Solntze II – nekropol’ ukreplennogo posele-niya srednei bronzy Ust’e. In N. O. Ivanova (ed.), Materialy po arheologii i etnogra-fii Uzhnogo Urala, 22–42. Chelyabinsk, Kamennyi poyas.

Epimakhov, A. V. 2005. Rannie komplexnye ob-schestva Severa Tzentral’noi Evraszii (po ma-terialam mogil’nika Kamennyi Ambar-5). Vol. 1. Chelyabinsk, Chelyabinskii dom pechati.

Epimakhov, A. V. 2009. Settlements and necro-polises of the Bronze Age of the Urals: op-portunities of reconstruction of social dyna-mics. In B. K. Hanks and K. M. Linduff (eds), Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals and Mobility, 74–90. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Epimakhov, A. V. and Koryakova, L. N. 2004. Streitwagen der eurasischen Steppe in der Bronzezeit: Das Wolga-Uralgebirge und Kasachstan. In M. Fansa and S. Burmeister (eds), Rad und Wagen. Der Ursprung einer Innovation. Wagen im Vorderen Orient und Europa, 221–236. Mainz, von Zabern.

Gening, V. F., Zdanovich, G. B. and Gening, V. V. 1992. Sintashta: arheologicheskie pamyat-niki ariyskikh plemen Uralo-Kazahstanskikh stepei. Vol. 1. Chelyabinsk, Uzhno-Ural’skoe knizhnoe izdatel’stvo.

Grigoriev, S. A. 2002. Ancient Indo-Europeans. Chelyabinsk, Rifei.

Hanks, B. K., Epimakhov, A. V. and Renfrew, A. C. 2007. Towards a Refined Chronology for the Bronze Age of the Southern Urals, Russia. Antiquity 81, 353–367.

Koryakova, L. and Epimakhov, A. V. 2007. The Urals and Western Siberia in the Bronze and Iron Age. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Logvin, V. N. 2002. The Cemetery of Bestamak and the Structure of the Community. In K. Jones-Bley and D. Zdanovich (eds), Complex Societies of Central Eurasia from the 3rd to the 1st Millennium BC: Regional Specifics in Light of Global Models, 189–201. Journal of Indo-European Studies, Monograph Series 45. Washington, Institute for Study of Man.

Medvedev, A. F. 1966. Ruchnoe metatel’noe oruzhie 9luk i strely, samostrel. VIII-XIV vv. Svod arheologicheskih istochnikov. Vyp. Е1-36. Moscow, Nauka.

Nelin, D. V. 1996. Luk i strely naseleniya Uzhnogo Zaural’ya i Severnogo Kazahstana epohi bronzy. In V.A. Ivanov (ed.), XIII Ural’skoe

Andrey Bersenev, Andrey Epimakhov and Dmitry Zdanovich

186

arheologicheskoe soveschanie, 60–62 Chast’ I. Ufa, Vostochnyi universitet.

Shishlina, N. I. 1990. O slozhnom luke srubnoi kul’tury. In S. V. Studzitzkaya (ed.), Problemy arheologii Evrazii. Trudy Gosudarstven-nogo istoricheskogo muzeya. Vyp. 74. 23–37. Moscow, Gosudarstvennyi istoricheskii mu-zei.

Solov’ev, A. I. 2003. Oruzhie I dospekhi. Sibirs-koe vooruzhenie: ot kamennogo veka do sred-nevekov’ya. Novosibirsk, Infolio-press.

Tkachev, V. V. 2007. Stepi Uzhnogo Priural’ya i Zapadnogo Kazahstana na rubezhe epoh sred-nei i pozdnei bronzy. Aktobe, Akyubinskii ob-lasnoi tzentr istorii, etnografii i arheologii.

Usachuk, A. N. 2005. Kamennoambarskie psalii (trassologicheskii analis). In A. V. Epimakhov (ed.), Rannie komplexnye obschestva Severa Tzentral’noi Evraszii (po materialam mogil’nika Kamennyi Ambar-5). Vol. 1, 179–189. Chelyabinsk, Chelyabinskii dom pechati.

Zdanovich, D. G. 2002. Introduction. In K. Jones-Bley and D. Zdanovich (eds), Complex

Societies of Central Eurasia from the 3rd to the 1st Millennium BC: Regional Specifics in Light of Global Models. Journal of Indo-European Studies, Monograph Series 45, ix–xxxviii. Washington, Institute for Study of Man.

Zdanovich, G. B. and Batanina, I. M. 2002. Paleography of the Fortified Centers of the Middle Bronze Age in the southern Trans-Urals according to Aerial Photography Data. In K. Jones-Bley and D. Zdanovich (eds), Complex Societies of central Eurasia from the 3rd to the 1st Millennium BC: Regional Specifics in Light of Global Models. Journal of Indo-European Studies Monograph Series 45, 120–138. Washington, Institute for Study of Man.

Zdanovich, G. B. and Zdanovich, D. G. 2002. The ‘Country of Towns’ of Southern Trans-Urals. In M. G. Levin (ed.), Ancient Interactions: east and west of Eurasia, 249–263. Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

Andrey BersenevArchaeology Scientific CentreCommuny st. 68 454000 ChelyabinskRussia

Andrey EpimakhovInstitute of History and Archaeology, South Ural branchCommuny st. 68 454000 ChelyabinskRussia

Dmitry ZdanovichChelyabinsk State University Brat’ev Kashirinykh st. 129454001 ChelyabinskRussia