The Scale validity of trust in political institutions ... · The scale validity of trust in...

Transcript of The Scale validity of trust in political institutions ... · The scale validity of trust in...

1

The scale validity of trust in political institutions measurements over time in Belgium.

An analysis of the European Social Survey, 2002-2010

Abstract

Within the literature, there is an ongoing debate about the dimensional structure of trust in

political institutions. While some authors assume this is a blanket judgment covering all

institutions equally, others claim this form of trust is experience-based and therefore

multidimensional. Based on five waves of the European Social Survey in Belgium, and using

multiple group confirmatory factor analysis, we demonstrate that trust in political institutions

is onedimensional, although it has to be acknowledged that some distinction between

representative political institutions and policy implementing institutions should be made. We

can demonstrate, furthermore, sufficient measurement stability over time, so that – with some

caution – trends over time can be constructed. We close with some observations about what

our results mean both for the theoretical status of political trust and for its evolution over time.

Keywords: political trust, measurement, over time equivalence, multiple group confirmatory

factor analysis, Belgium

Introduction

The evolution of political trust is a topic of ongoing concern in the literature. Since Easton

(1965) it is assumed that that trust in political institutions functions as a form of diffuse

support for the political system, and therefore is an important resource for the stability of

democratic political systems. It is less clear, however, whether in the current era levels of

political trust are declining, as some authors have argued (Inglehart & Catterberg, 2002), or

whether they should rather be seen as stable (Marien, 2011). Analyzing this question is not

just an empirical matter. In the literature, two competing views on the nature of political trust

can be found. Some authors consider political trust as a form of blanket judgment, covering

the entire political system. If this is the case, we can assume that political trust has a rather

stable structure and changes only slowly over time. Looking at the pattern of geographical

distribution of political trust levels, it can indeed be observed that these differences do not

seem to change much over time (Hooghe, 2011; Uslaner, 2002). Other authors, however, are

2

more strongly inclined to see trust as an assessment of the actual functioning of political

systems. The underlying logic is that institutions will be judged by public opinion on their

own merits, and that as a consequence citizens will express specific trust in specific

institutions (Bovens & Wille, 2008; Van de Walle, Van Roosbroek & Bouckaert, 2008).

While the first conceptualization of political trust would imply that trust in political

institutions is a solid one-dimensional latent concept, in the second, experience-based

conceptualization, we do expect changes to occur in the relation between the individual items.

Unless the performance of all government institutions would develop in exactly the same

manner, one can expect that the satisfaction with some institutions will drop, while for others

it will rise.

In this paper, our aim is to analysis the scale validity of trust in political institutions over five

observation points in the first decade of the 21st century. The analysis is conducted in

Belgium, a country that has known some substantial turmoil during this period. Belgium,

therefore can be considered a conservative test: in a divided and volatile political system like

Belgium, it is more likely that trust in political institution will not be a one-dimensional latent

concept.

Literature

The importance of political trust has been widely recognized in political science literature.

Most authors believe that a high level of political trust leads to acceptance of and compliance

with political decisions (Marien & Hooghe, 2011). It is argued that trust in political

institutions motivates citizens to assign a greater role to those institutions in providing

collective goods for society (Hetherington, 1998). The theoretical status of this form of trust,

however, is highly disputed. Hardin (2002) has even made the case that trusting political

institutions for most citizens is not warranted at all, since they do not have the necessary

information to arrive at a well-informed decision about the trustworthiness of those

institutions.

Within the literature on trust in political institutions, two main research lines can be

distinguished: while some authors see this form of trust as diffuse and one-dimensional,

others see it as experience-based and therefore multi-dimensional.

Easton (1965) already argued that trust in political institutions first of all should be

understood as a form of diffuse support, that is not related to the functioning of specific

3

institutions or office-holders. Rather, it should be seen as a general disposition toward the

function of the political system as a whole, and as such it forms a stable base for the perceived

legitimacy of that system. It has been argued therefore that trust in political institutions is not

based on actual experiences, but rather amounts to a general judgment about the way the

political system as a whole functions (Hetherington, 2005). This claim is further supported by

the fact that among adolescents too, rather stable and well-structured attitudes with regard to

political trust have already been found, even although they did not have any experience with

any one of these institutions themselves (Claes, Hooghe, & Marien, 2012). Hooghe (2011) has

made the point that such a blanket judgment, covering all forms of institutions in an equal

manner, can still be rational. Research on quality of government has shown that there is a very

strong correlation between the performance of various government agencies (Rothstein 2012).

It can argued, therefore, that there is a general political culture, governing the conduct of

political elites, no matter what specific function they have in the system. As Hooghe (2011,

275) summarizes it: “Looking at studies on corruption, there are no examples of countries

where Members of Parliament are corrupt but the government is clean. The degree of

trustworthiness is therefore not an individual characteristic of a person, or even of a political

party or an institution, but of the political system as a whole. As such it makes sense that my

opinion on various actors loads on a single latent variable.” The assumption in this line of the

literature, therefore, is that citizens do not make any distinctions with regard to the way

institutions as such perform.

Other authors, however, claim more strongly that citizens do react to either the performance

of institutions, or to their actual experience with some of these institutions (Bovens & Wille,

2008; Damico, Conway, & Damico, 2000). Furthermore, it is argued that the norms governing

various institutions will differ: it is expected that e.g. Members of Parliament will behave in a

different manner than e.g. police officers or judges (Fisher, Van Heerde, & Tucker, 2010).

This experience-based conception of trust in political institutions therefore pays much more

attention to rapid fluctuations in trust levels. It can be assumed, e.g., that a corruption scandal

in Parliament will lead to lower levels of trust in Parliament, while it should not have an

impact on the level of trust in e.g., the police or the courts (Bovens & Wille, 2008). This view

also implies that trust measurements can be used to some extent as a proxy for satisfaction

measurements: if some institutions develop a policy that will augment the quality of the

services they provide to the public, this should, in the long or the short run, result in higher

levels of trust in this specific institution (Van de Walle, Van Roosbroek & Bouckaert, 2008).

4

Rothstein and Stolle (2008) argue more specifically that citizens in this respect make a

distinction between two groups of institutions. On the one hand, there are the institutions of

representative democracy (Parliament, parties, politicians and ministers), where it is assumed

that office holders here should be held accountable to public opinion. For the institutions of

law and order (police, the courts…) on the other hand, we expect less accountability, but

impartiality is here the main guiding norm. Rothstein and Stolle argue therefore that in stead

of lumping all these institutions together into a diffuse measurement, both dimensions should

be clearly distinguished.

The theoretical discussion about the status of a trust in political institutions measurement is

directly relevant to the ongoing debate about the trends in political institutions. If trust in

political institutions is indeed a blanket judgment, the scale can be used in a rather

straightforward manner to assess trends over time in the level of political trust. If however,

trust in political institutions is multi-dimensional, this implies that it is not methodologically

correct to make general statement about “trust in political institutions”. In that case, it is

perfectly possible that e.g., the trust in Parliament would rise, while the trust in the courts

would decline. Furthermore, it remains to be ascertained in that case whether the dimensional

structure is stable over time, as some institutions might become more salient than others over

time (Allum, Read, & Sturgis, 2011; Marien, 2011; Van de Walle, Van Roosbroek, &

Bouckaert, 2008).

Based on the literature therefore, we can arrive at the main research question, which is: can

trust in political institutions be considered as a one-dimensional concept, and if so, is this

measurement equivalent over time?

Data and methods

European Social Survey

To examine our research question we use data form the European Social Survey (ESS). The

original goal of the ESS was to design a survey that could chart and help to explain the

interaction between Europe’s changing institutions and the attitudes, beliefs and behavioural

patterns of its population (European Social Survey, 2012). The first round of data collection

was conducted in 2002. Since then the survey is held biannually. The battery on trust in

political institutions has been included in every round of the ESS (Stoop, Jowell, & Mohler,

2002). This means we can use all current available data for our analyses, meaning data the

years 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2010.

5

The battery measuring trust in political institutions as found in the ESS is as followed: “Using

this card, please tell me on a score of 0-10 how much you personally trust each of the

institutions I read out. 0 means you do not trust an institution at all, and 10 means you have

complete trust.” The institutions are the country’s parliament, the legal system, the police,

politicians, political parties, the European parliament and the United Nations (UN).

Unfortunately we cannot take trust in political parties into account during the analysis,

because this item is not asked in the first round and given our research question it is important

to include only items that were asked in an identical manner in all five waves of the European

Social Survey.

The Belgian case

The ESS is a cross-country survey that is being conducted in over 30 European countries.

This makes the data ideal for cross-national comparison (Allum et al., 2011). In this paper,

however, we are not interested in cross-cultural measurement equivalence, as this topic

already has been investigated in other studies, but rather in measurement equivalence over

time. In order not to confound both forms of measurement equivalence, in the current

manuscript we limit ourselves to just one country, where we have opted for Belgium. We

have done so, first because with regard to the level of trust in institutions, Belgium can be

considered as an average case for Western Europe. Second, however, it is a political system

that is plagued by an endemic legitimacy crisis. Back in the 1990s, Belgium was first hit by a

shock with regard to trust in political institutions when it turned out that the police and the

courts had bungled the investigation toward a serial child murderer (Hooghe, 1998). During

our observation period, Belgium experienced a number of political crises as a result of the

ongoing debates between the Dutch and the French language group. Since 2007 Belgium has

known governmental instability, and the 2010 elections led to the electoral breakthrough of a

separatist party that wants to break up the country in three independent regions (Deschouwer,

2012). Belgium, therefore, can be considered as a conservative test. We can assume that

public opinion in the country will express different judgments in the various branches of

government, and judgments might differ between the federal and the regional level.1 If, even

in these circumstances, trust in political institutions still proves to be one-dimensional and

equivalent over time, this offers firm support for the ‘blanket judgment’ hypothesis.

6

Methods

Initially we conducted a principal component analysis (PCA) using SPSS. The goal of this

analysis is to simplify the correlation matrices. It tests whether different variables can be

accounted for by a small number of factors (Kline, 1994). Subsequently we conducted a

confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) per round of data collection using Mplus (Muthén &

Muthén, 2012). This model will be used for the further analyses. The model will be evaluated

by investigating the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and comparative

index (CFI). The RMSEA is used to test the model based on an absolute fitwhile the CFI is

used to evaluate the fitted CFA solution. To test for over-time measurement invariance we

conduct a multiple group factor analysis (MGCFA), again using Mplus software (Muthén &

Muthén, 2012). This method entails five hierarchical levels (Steenkamp & Baumgartner,

1998).

The first level is configural invariance, which basically means that the pattern of salient and

non-salient loadings has to be the equal across all groups. This form of invariance states if the

construct political trust can be measured using a single factor in all rounds of data collection.

The next level is metric invariance. In this form of measurement invariance, factor loadings

on the items are fixed to be equal among all years. When metric invariance is established,

mean scores on items can be compared meaningful across observations. The third level is

scalar invariance. This is an even stricter test because here also the intercepts are constrained

to be equal across all years (Rensvold & Cheung, 1998). Scalar invariance is required to

conduct latent mean comparisons across groups and time, which is more robust than mean

score comparisons (Allum et al., 2011). As mentioned, measurement invariance test have a

fourth and fifth level, which test for factor covariance invariance and error variance

invariance respectively (Steenkamp & Baumgartner, 1998). These tests fall out of the scope of

this article though, since we only want to compare latent means to detect trends and in

practice these levels are never investigated in this kind of survey research.

We will conduct the MGCFA according to the method suggested in the previous paragraph.

This means that during a first round we will test for configural invariance, during a second for

metric invariance and during a third for scalar invariance. Even though strictly speaking the

indicators are ordinal, with 10 discrete points, we regard them as continuous for the analysis

(Allum et al., 2011). As estimator we use maximum likelihood (ML) because the distribution

of the data is approximately normal. ML is considered to be the most robust estimator when

not much distortion occurs (Bollen, 1989). To test for model fit every round, we rely on three

different fit indices (Bollen & Long, 1992; Bollen, 1989; Mulaik, 2007). The basic goodness-

7

of-fit test is the chi-square test (χ²). Unfortunately this test is highly sensitive for large sample

sizes. This means that it will indicate significant differences, even if in reality the differences

are small (Bollen & Long, 1992; Rensvold & Cheung, 1998). Especially in cross-national and

longitudinal research this can be problematic, since they usually deal with a large sample size.

That is why, in addition to the chi-square test, we take two other model fits into account, the

RMSEA and CFI. These three model fit indices should complement each other (Bollen &

Long, 1992; Mulaik, 2007).

Results

The first test is a principal component analysis that allows us to establish whether or not

political trust is a one dimensional construct. The results in Table 1 show that the items only

measure one component or construct. This means that political trust is indeed, and quite

strongly, a one dimensional concept. The results also give us a first indication of the items.

They all load highly on the construct, which indicates a good model. But this has to be further

examined by testing for invariance while conducting a confirmatory factor analysis.

Table 1. Results of PCA for all rounds of ESS.

Component

round 1

Component

round 2

Compontent

round 3

Component

round 4

Component

round 5

Trust in Belgian

parliament

0.824 0.809 0.822 0.824 0.821

Trust in legal system 0.774 0.783 0.767 0.789 0.786

Trust in police 0.690 0.668 0.653 0.701 0.691

Trust in politicians 0.846 0.821 0.795 0.810 0.799

Trust in European

parliament

0.845 0.827 0.840 0.840 0.865

Trust in UN 0.751 0.737 0.753 0.768 0.780

Eigenvalue 3.750 3.613 3.596 3.745 3.766

Explainedvariance 62.49% 60.22% 59.93% 62.42% 62.76%

N 1600 1627 1691 1667 1637 Entries are the result of a principal component analysis for the Belgian survey in all rounds of ESS.

The next step is to test for configural invariance. We investigate the factor loadings and error

variance for all rounds, which are summarized in Table 2. The factor loadings represent the

relationship between the latent construct and the items. A factor loading is considered salient

when it has a value above 0.30 (Brown, 2006). The error variance is the opposite,it is the part

of the item that is not explained by the latent construct. As Table 2 shows, all items have a

8

factor loading above 0.30. This means that the item measurement contributes significantly to

the latent concept of trust in political institutions. This allows us to proceed with our analyses.

However, we can notice some interesting features when looking at Table 2 where we

investigate configural invariance. The factor loadings on the measures of trust in

representational institutions (i.e., parliaments and politicians) are higher than the factor

loadings on the implementing institutions (i.e. legal systems and the police) and the United

Nations. Correspondingly, the error variance is higher for the latter. Although these

differences do not endanger the one-dimensional character of the concept, this does lend some

support to the observation of Rothstein and Stolle (2008) that both dimensions should be

distinguished.

9

Table 2. Configural invariance for trust in institutions (ESS for Belgium).

Wave 2002 Wave 2004 Wave 2006 Wave 2008 Wave 2010

Factor

loading

Error

variance

Factor

loading

Error

variance

Factor

loading

Error

variance

Factor

loading

Error

variance

Factor

loading

Error

variance

Belgian

parliament

0.819 0.328 0.798 0.363 0.824 0.322 0.825 0.319 0.819 0.329

Politicians 0.843 0.290 0.814 0.337 0.782 0.389 0.802 0.357 0.787 0.381

Legal system 0.677 0.542 0.695 0.517 0.660 0.565 0.700 0.510 0.700 0.510

Police 0.555 0.692 0.533 0.715 0.519 0.731 0.571 0.674 0.566 0.680

EU parliament 0.786 0.383 0.769 0.408 0.768 0.411 0.766 0.413 0.804 0.535

United Nations 0.634 0.598 0.607 0.632 0.628 0.605 0.647 0.581 0.661 0.563 Source: ESS 2002-2010 + own calculations .Notes: standardized factor loadings and error variance from a MGCFA with no constraints on the full sample. Fit indices: χ² =

1839.844; df = 45; p-value = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.149; CFI = 0.927; N (wave 2002) = 1889; N (wave 2004) = 1776; N (wave 2006) = 1798; N (wave 2008) = 1760; N (wave

2010) = 1704.

10

In Table 3 we investigate covariance between items, more specifically covariance between

trust in the legal system and trust in the police. Because of the established covariance the

error terms between these two items are allowed to correlate in our model. The final remark is

about the high level of variance between trust in the European parliament and trust in United

Nations. By allowing these items to correlate, we improve the measurement fit.

Table 3. Allowed correlations to improve model fit.

Wave 2002 Wave 2004 Wave 2006 Wave 2008 Wave 2010

Factor

loading

S.E. Factor

loading

S.E. Factor

loading

S.E Factor

loading

S.E Factor

loading

S.E

Police with

legal

system

0.247 0.024 0.292 0.024 0.314 0.023 0.318 0.024 0.305 0.024

EU

parliament

with UN

0.392 0.024 0.338 0.026 0.432 0.023 0.406 0.024 0.467 0.023

Source: ESS 2002-2010 + own calculations. Notes: standardized factor loadings and standard error from a

MGCFA with no constraints on the full sample. Improved fit indices: χ² = 136.644; df = 35; p-value = 0.000;

RMSEA = 0.040; CFI = 0.996; N (wave 2002) = 1889; N (wave 2004) = 1776; N (wave 2006) = 1798; N (wave

2008) = 1760; N (wave 2010) = 1704.

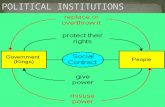

This leads us to the measurement model presented in Figure 1. After conducting a MGCFA,

this model provides an excellent fit, which indicates configural invariance. The RMSEA

equals to 0.040, which is according to generally accepted standards (Brown, 2006). Our

model has a CFI equal to 0.996, which again indicates a very good fit. Therefore, this model

will be used for the other measurement invariance tests

Figure 1. Measurement model of political trust. Notes: standardized factor loadings and error variance from a

MGCFA with no constraints on round 1 of ESS. The standardized factor loadings and error variance from a

MGCFA with no constraints on the other four rounds are shown in Appendix A.

11

We proceed to test for metric invariance. We conduct another MGCFA but now we constrain

all factor loadings to be equal across the five rounds. Figure 2 summarizes the factor loadings

and error variance of this analysis. We can observe the same conclusions as before: all items

still measure one latent variable and there is still some difference between the representational

and implementing institutions. But more important are the model fit indices. The added

constraints do not worsen the fit. The RMSEA even improves a little (RMSEA = 0.030) and

the CFI decreases negligible (CFI = 0.995). Moreover the chi-square ratio is not significant

(Δχ² = 45.800; df = 32). This means that the chi-square test shows no significant difference

between the configural and metric model. We can thus conclude that the measurement of

political trust is metric invariant.

Figure 2. Metric invariance for the political trust scale in all waves. Notes: standardized factor loadings and

error variance from a MGCFA with metric constraints on the full sample. Metric constraints: the factor loadings

are constrained across all waves, while the intercepts, error terms and variance of the latent concept are free. Fit

indices: χ² = 197.893; df = 75; p-value = 0.000; RMSEA = 0.030; CFI = 0.995; N= 8927.

To test for scalar invariance, we constrain the intercepts to be equal across all rounds, in

addition to the previous restrictions on the factor loadings. The results of this test are shown in

Table 4. We were not able to detect full scalar invariance since the chi-square ratio was

significant (Δχ² = 434.827; Δdf = 20). This means we cannot safely compare latent means

across time. This result is, however, not surprising. While interpreting metric invariance we

found a dichotomy between types of institutions and this makes it harder to establish scalar

invariance. However, according to Byrne, Shavelson, & Muthén (1989), we can still test for

partial scalar invariance. If this can be confirmed, we can still compare the latent means. We

12

followed Sörbom & Jöreskog's (1982) method to establish this. We first determine which

round has the highest chi-square contribution, then, according to modification indices, we

release the constraint on the intercept of a particular item.

Table 4 summarizes the model build-up toward partial scalar invariance. We had to relax the

constraints on 5 items before establishing scalar invariance. For round 2002, 2008 and 2010

we relaxed trust in politicians. Additionally, we relaxed trust in the Belgian parliament for

round 2002 and 2006. From this we conclude that the measurement of political trust is partial

scalar invariant (Δχ² = 84.349; Δdf = 15), especially since we were able to obtain an excellent

model fit (RMSEA = 0.036, CFI = 0.992).

The relaxed items can be explained by looking back at the score means (Table 5). First we

notice that in almost every round the intercept of trust in parliament is relaxed (round 2002,

2008 and 2010). This is not surprising since the score means of trust in parliament has strong

fluctuations between the rounds. The same explanation holds for trust in politicians. Trust in

legal systems, trust in the police, trust in the European parliament and trust in the UN were

less subjected to changes throughout all rounds. Therefore it makes sense that these item did

not need to be relaxed because the intercepts were already more or less equal.

13

Table 4. Scalar invariance models for across time equivalence (ESS).

Model χ² df RMSEA CFI Wave with highest

contribution

χ² contribution

1. Configural invariance 136.644 35 0.040 0.996

2. Metric invariance 182.444 67 0.031 0.995

3. Scalar invariance 617.271 87 0.058 0.978 Wave 1 parliament 107.824

4. Free wave 1 τparliament 504.753 86 0.052 0.983 Wave 1 politicians 116.303

5. Free wave 1 τpolitician 386.093 85 0.045 0.988 Wave 3 parliament 38.962

6. Free wave 3 τparliament 374.893 84 0.044 0.988 Wave 5 politicians 26.894

7. Free wave 5 τpolitician 347.658 83 0.041 0.989 Wave 4 politicians 37.706

8. Free wave 4 τpolitician 266.793 82 0.036 0.992 Source: ESS 2002-2010 + own calculations. Test statistic for the entire sample.Notes: results are the test statistics of a MGCFA with scalar constraints: the factor loadings and

intercepts are constrained, error terms and variance of the latent concept are free.

14

By establishing partial scalar invariance, we are allowed to compare latent mean scores.

However, we have to be careful with our conclusions since they are not based on full scalar

invariance. The latent means indicate that political trust stays more or less stable over time.

When calculating the chi-square ratio to determine whether or not the latent means in the later

rounds are different from the initial situation, we found they do not differ significantly.

By establishing metric invariance, we can compare mean scores (intercepts) on the items over

the different rounds. The mean scores are summarized in Table 5, which shows some

interesting observations. First, we see an overall decline in the trust in the Belgian parliament.

Trust in the legal systems and police, on the other hand, slightly increase. These institution are

not affected by the political turmoil. Trust in the European parliament increases first, but

declines from 2008 onward.

To Summarize, trust in the implementing institutions seems to increase, while trust in the

representational institutions of Belgium seems to decrease during political instability. This

could have important implications. It suggests that citizens to some extent evaluate these two

types of institutions differently. However, to obtain an even better view on the evolution of

political trust, we still have to establish scalar invariance.

Table 5. Mean scores (intercepts) of metric model.

Wave 2002 Wave 2004 Wave 2006 Wave 2008 Wave 2010

Trust in Belgian

parliament

2.215 2.104 2.282 2.113 1.992

Trust in

politicians

1.949 1.951 1.974 1.867 1.738

Trust in legal

system

1.743 2.029 1.997 2.076 2.079

Trust in police 2.449 2.593 2.682 2.754 2.585

Trust in EU

parliament

2.109 2.231 2.311 2.297 2.286

Trust in UN 2.096 2.153 2.286 2.359 2.380 Source: ESS 2002-2010 + own calculations. N (wave 2002) = 1889; N (wave 2004) = 1776; N (wave 2006) =

1798; N (wave 2008) = 1760; N (wave 2010) = 1704

Note: standardized intercepts of all political trust items, based on the results of the metric model.

15

Table 6. Comparison of structural and latent wave means (all waves).

Structural mean Latent mean

µ Rank Ƙ Rank

Round 2002 4.93 0.00

Round 2004 5.00 1 0.17 2

Round 2006 5.18 4 0.23 4

Round 2008 5.07 3 0.21 3

Round 2010 5.01 2 0.17 1 Source: ESS 2002- 2010 + own calculations.

Note: µ is the symbol for the structural mean of political trust, constructed by the means of the sum scale of the

six political trust items. Ƙ is the symbol for the latent mean of political trust, as shown in the output of the

multiple group CFA.

We established metric and partial scalar invariance for the measure of the latent construct

political trust. These equivalence tests are however not a goal by themselves. We now finally

arrive at the main question: do these test contribute something to the understanding of the

development of political trust over time? To answer this question we compare the structural

means with the latent means, which were obtained by testing for measurement equivalence

with multiple group SEM. To be able to interpret the means correctly, we have to note that the

latent mean of round 2002 was fixed to equal zero and the other rounds has to be interpret in

comparison. This is why the first round is not included in the ranking. Consequently, the

structural mean of round 2002 is also not included in the ranking.

For the first and second place we notice that round 2004 and 2010 switch positions, although

their scores are very similar (they switched position since the latent mean for round 2004

equals 0.172 and the latent mean for round 2010 equals 0.167). This difference is however

neglectable. The ranking of the structural means and latent means for round 2006 and 2008 do

not differ. Following this, the impact of using latent means should not be overstated, since

both types of means lead to more or less similar conclusions.

Discussion

In this paper the goal was to establish ?? the dimensional character of trust in political

institutions and the measurement equivalence over time. This was done by conducting a

principal component analysis and a confirmatory factor analysis on Belgian data from 2002,

2004, 2006, 2008 and 2010. The conclusion has to be that trust in political institutions, even

in Belgium, is a one-dimensional latent concept, although it has to be acknowledged that we

16

do find some distinction between on the one hand the institutions that have a representative

function, and on the other hand institutions that implement policy.

We found the political trust measure to be metric and partially scalar invariant. This could

provide researchers with insights on how to handle political trust questions. Establishing

metric invariance entails that factor loadings of the measurement items are equal over time

and that the mean scores may be compared over time. Additionally, this is an indication that

political trust remains stable over time. As we have seen, we could not establish full scalar

invariance. Some items seem to be highly subjected to changes between rounds, such as trust

in parliament and trust in politicians. However, after relaxing the constraints on these items,

partial scalar invariance was established. This is a further indication that political trust is

actually stable over time and not declining as some authors claim.

When this was established, we wanted to look at the trends in political trust. When looking at

the items separately, we noticed some variation. Trust in the representational institutions

(parliament, politicians) is in fact declining over the years. However, trust in the

implementing (legal systems, police) and international institutions (United Nations and

European parliament) remains stable or is even increasing. The conclusion therefore is that, at

least for the Belgian case, there is no overall decline in trust in political institutions, but that

we do see variations across various institutions.

Furthermore, we wanted to examine whether equivalence test actually contribute to the

understanding of the development of political trust. When comparing the structural and latent

means, we found that these do not differ in a significant manner.

17

References

Allum, N., Read, S., & Sturgis, P. (2011). Evaluating change in social and political trust in

Europe. In E. Davidov, P. Schmidt, & J. Billiet (Eds.), Cross-Cultural Analysis. Methods

and Applications (pp. 35–53). New York, NY: Routledge.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley.

Bollen, K. A., & Long, J. S. (1992). Tests for Structural Equation Models: Introduction.

Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 123–131.

Bovens, M., & Wille, A. (2008). Deciphering the Dutch drop: ten explanations for decreasing

political trust in The Netherlands. International Review of Administrative Sciences,

74(2), 283–305.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: The

Guilford Press.

Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J., & Muthén, B. (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor

covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance.

Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 456–466.

Claes, E., Hooghe, M., & Marien, S. (2012). A Two-Year Panel Study among Belgian Late

Adolescents on the Impact of School Environment Characteristics on Political Trust.

International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 24(2), 208–224.

Damico, A. J., Conway, M. M., & Damico, S. B. (2000). Patterns of Political Trust and

Mistrust: Three Moments in the Lives of Democratic Citizens. Polity, 32(3), 377–400.

Deschouwer, K. (2012). From Protest to Power: Autonomist Parties and the Challenges of

Representation. West European Politics, 36 (1), 289-291.

Fisher, J., Van Heerde, J., & Tucker, A. (2010). Does One Trust Judgement Fit All? Linking

Theory and Empirics. British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 12, 161–188.

Hardin, R. (2002). Trust and Trustworthiness. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The Political Relevance of Political Trust. American Political

Science Review, 92(4), 791–808.

Hetherington, M. J. (2005). Why Trust Matters. Declining Political Trust and the Demise of

American Liberalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hooghe, M. (1998). Selectieve uitsluiting in het Belgisch politiek systeem. Innovatie en

protest door nieuwe sociale bewegingen. Res Publica, 40(1), 3–21.

Hooghe, M. (2011). Why There is Basically Only One Form of Political Trust. British

Journal of Politics & International Relations, 13(2), 269–275.

Kline, P. (1994). An easy guide to factor analysis. London: Routledge.

18

Lipset, S. M., & Schneider, W. (1983). The Decline of Confidence in American Institutions.

Political Science Quarterly, 98(3), 379–402.

Marien, S. (2011). Measuring political trust across time and space. In S. Zmerli & M. Hooghe

(Eds.), Political trust. Why Context Matters. Colchester: ECPR, University of Essex.

Marien, S., & Hooghe, M. (2011). The Effect of Declining Levels of Political Trust on the

Governability of Liberal Democracies. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the

Political Studies Association. London.

Miller, A. H., & Borrelli, S. A. (1991). Confidence in Government During the 1980s.

American Politics Research, 19(2), 147–173.

Mulaik, S. (2007). There is a place for approximate fit in structural equation modelling.

Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 883–891.

Muthén, B. O., & Muthén, L. K. (2012). Mplus user’s guid (7th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén &

Muthén.

Rensvold, R. B., & Cheung, G. W. (1998). Testing Measurement Models for Factorial

Invariance: A Systematic Approach. Educational and Psychological Measurement,

58(6), 1017–1034.

Rothstein, B., & Stolle, D. (2008). The State and Social Capital An Institutional Theory of

Generalized Trust. Comparative Politics, 40(4), 441–459.

Sörbom, D. ., & Jöreskog, K. G. . (1982). The use of structural equation models in evaluation

research. In C. Fornell (Ed.), A Second Generation of Multivariate Analysis: Vol .2.

Measurement and evaluation (pp. 381–418). New York: Praeger.

Steenkamp, J.-B. ., & Baumgartner, H. (1998). Assesing measurement invariance in cross-

national consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 25(1), 78–107.

Stoop, I., Jowell, R., & Mohler, P. (2002). The European Social Survey: one survey in two

dozen countries. ?? Plaats?

European Social Survey (2012). Norway: Service, Norwegian Social Science Data. Retrieved

from http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/

Uslaner, E. M. (2002). The Moral Foundations of Trust. New York: Cambridge University

Press.

Van de Walle, S., Van Roosbroek, S., & Bouckaert, G. (2008). Trust in the public sector: is

there any evidence for a long-term decline? International Review of Administrative

Sciences, 74(1), 47–64.

19

Appendix A

Figure 1, Appendix A: Solution Confirmatory Factor Analysis (wave 2004).

Figure 2, Appendix A: Solution Confirmatory Factor Analysis (wave 2006).

20

Figure 3, Appendix A: Solution Confirmatory Factor Analysis (wave 2008).

Figure 4, Appendix A: Solution Confirmatory Factor Analysis (wave 2010).

Endnotes

1. It has to be noted, of course that in Belgium two different language groups have to be

distinguished. If we split the sample however between Dutch and French speaking

respondents, it can be observed that the structure of the attitudinal scale is the same in both

language communities. While the level of political trust tends to be lower in the French

speaking part of the country, this does not have an effect on the measurement qualities of the

scale.