The Roles of trigona spp bees in crops

-

Upload

faizal-razali -

Category

Documents

-

view

158 -

download

4

description

Transcript of The Roles of trigona spp bees in crops

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1999. 44:183–206Copyright c© 1999 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

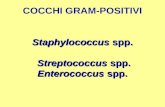

THE ROLE OF STINGLESS BEESIN CROP POLLINATION

Tim A. HeardCSIRO Entomology, PMB 3 Indooroopilly 4068, Australia;e-mail: [email protected]

KEY WORDS: Apidae, Meliponini, floral biology, alternative pollinators, entomophily

ABSTRACT

Stingless bees (Apidae: Meliponini) are common visitors to flowering plants inthe tropics, but evidence for their importance and effectiveness as crop pollina-tors is lacking for most plant species. They are known to visit the flowers of∼90crop species. They were confirmed to be effective and important pollinators of9 species. They may make a contribution to the pollination of∼60 other species,but there is insufficient information to determine their overall effectiveness orimportance. They have been recorded from another 20 crops, but other evidencesuggests that they do not have an important role because these plants are pol-linated by other means. The strengths and limitations of stingless bees as croppollinators are discussed. Aspects of their biology that impact on their potentialfor crop pollination are reviewed, including generalized flower visiting behaviorof colonies, floral constancy of individual bees, flight range, and the importanceof natural vegetation for maintaining local populations.

INTRODUCTION

Stingless bees are a group of small- to medium-sized bees, with vestigial stings,found in tropical and many subtropical parts of the world. They are the majorvisitors of many flowering plants in the tropics. They show a level of socialorganization comparable to that of honey bees (131). Colonies are perennialand usually consist of hundreds or thousands of workers (160).

The estimated several hundred species of stingless bees are arranged into21 genera (79). The rank of the group has varied but recently has been placedat tribe (122). The most important genera areMeliponaandTrigona. Melipona

1830066-4170/99/0101-0183$08.00

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

184 HEARD

consists of∼50 species, is confined to the neotropics, has more complex com-munication systems (88), and is capable of buzz pollination (i.e. ejecting pollengrains by vibration of the pollen-bearing anthers of flowers that dehisce pollenthrough pores) (24).Trigona is the largest and most widely distributed genus,with ∼130 species in∼10 subgenera, including the neotropicalTrigonasensustricto and most of the Asian Meliponini.

It is often stated that stingless bees are important pollinators of crops intropical and subtropical parts of the world (29, 37, 77, 78, 158). The evidencefor these assertions has never been reviewed. Reviews on the role of non-Apisbees in crop pollination mention stingless bees either briefly (19, 93, 97) or notat all (121, 147). Books on crop pollination by insects treat the topic in a littlemore detail (37, 77, 125). This neglect probably reflects a lack of knowledgerather than a lack of importance.

The use and management of non-Apisbees and other insects for crop polli-nation is important because of the almost total reliance of world agriculture onhoney bees. In many locations and for many crops, the ability of honey bees topollinate is threatened or limited because of factors such as Africanization, dis-eases and parasites, low efficiency on some crop species, climatic limitations,and economic pressures (93).

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF STINGLESSBEES FOR CROP POLLINATION

Many characteristics of stingless bees resemble those of honey bees. Some ofthe characteristics that influence their ability as pollinators are (a) polylecty andadaptability, which enable them to pollinate multiple plant species and adaptto new ones (see below for references); (b) floral constancy: A worker on atrip usually visits only one plant species (108); (c) domestication: Coloniescan be placed in hives, inspected, propagated, fed, requeened, controlled forenemies, transported, and otherwise managed (91); (d ) perennial colonies,which allow workers to forage continuously within climatic constraints andobviate the need to develop colonies each year; (e) large food reserves arestored in nests: This has the obvious benefit of allowing colonies to survivelong periods of low food availability. Additionally, it means that workers willcollect floral resources beyond immediate needs, resulting in intensive visitationof preferred flowers (129); (f ) possibility of in-hive pollen transfer, decreasingthe need for bee movement between plants of self-incompatible species: Thishas been found for honey bees (30) and is equally likely for stingless bees;(g) forager recruitment: Workers recruit nest mates to rewarding floral resourcesand provide information on the position of those floral resources, which allowsthe rapid deployment of large numbers of foragers (88) relative to other beesand insects in which each individual has to find the resource.

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 185

Unlike honey bees, stingless bees have the following advantages: They aregenerally less harmful to humans and domesticated animals; they are able toforage effectively in glasshouses (63); propagation of colonies contributes topreservation of biodiversity by conserving populations of species that mayotherwise decline owing to human disruption of ecosystems; colonies are rarelyable to abscond, as the old queen is flightless (57); and they are resistant to thediseases and parasites of honey bees (31). Thus a honey bee epizootic thatdisrupted pollination would not effect the stingless bees in that system.

Disadvantages of stingless bees for crop pollination include the following:There is a poor level of domestication technology for most species; there is a lackof availability of large numbers of hives; colony growth rates are low comparedwith honey bees; some species are unable to be domesticated because of specificnesting requirements; some species damage leaves in search of resin (25, 158);and some species are territorial and fight when placed in close proximity.

ASPECTS OF THE BIOLOGY OF STINGLESSBEES RELEVANT TO POLLINATION

The biology of the stingless bees has been reviewed (78, 124, 130, 160) butnever from the perspective of crop pollination. Aspects of the foraging biologyof stingless bees that are pertinent to this topic are reviewed here. Several otherrelevant topics including foraging syndromes, navigation, forager recruitment,response to weather, floral larceny, and diet and seasonal patterns of activityare reviewed by Roubik (124).

Stingless bees are generalist flower visitors. All studied species visit a broadrange of plant species. For example,Hypotrigona pothieriused 54 species in28 families (69),Melipona marginataused 173 species in 38 families (67), andMelipona favosavisited 38 species in 26 families (34). The number of plantspecies visited for nectar may be higher than the number visited for pollen(67, 109). Despite their generalized flower selection, all examined species showpreferences (67, 69, 109, 128). Stingless bees are adaptable, rapidly learningto exploit the resources offered by introduced plants. For example, neotrop-ical stingless bees heavily use the introducedEucalyptusspp. (43, 67). Fewgeneralizations can be made regarding the plant or flower type preferred bystingless bees, but it has been suggested they prefer small flowers (161), denseinflorescences (128), flowers with corolla tubes shorter than the bee’s tongues(50), flowers with long corolla tubes that are wide enough for the bees to enter(34), trees (67, 109, 110), and white or yellow flowers (27).

Floral constancy, in which a worker visits only one plant species on a singletrip, is typical of many polyphagous bees (33). In Brazil, 97% of the pollenforagers of nine species of stingless bees visited only one floral resource oneach trip, as evidenced by the pure pollen loads in their corbiculae (108). Floral

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

186 HEARD

constancy is associated with pollinator effectiveness, as collection and deposi-tion of pollen from two or more species reduces the amount of pollen availableand contaminates stigmas with the wrong pollen. In addition to floral speciesconstancy, foragers normally show resource constancy to either nectar, pollen,or resin within a single trip and usually between successive trips (58, 141).

In addition to records of use of many plants by stingless bees, they have beenshown to be important pollinators of noncrop species in natural habitats. Exam-ples of these studies were conducted at the community and individual specieslevels. Of 41 plant species investigated in the forest understory in Sarawak,9 were pollinated by stingless bees (64). In the lowland neotropics, all of the52 species visited byMeliponaand 108 of the 128 species visited by other sting-less bee species may have benefited directly from pollination services of thesebees (123). At the species level, stingless bees are the confirmed pollinators ofmany plants on the basis of experimentation or observation.Trigonaspp. werethe most abundant and effective pollinators of the androdioeciousXerospermumintermediumgrowing in the understory of Malaysian rainforests (8). Anothersapindaceous rainforest understory tree in Costa Rica,Cupania guatemalensis,is also pollinated byTrigona spp. (14).Trigona bees were shown to be ef-fective pollinators ofSpathiphyllum friedrichsthalii(83). Of the 13 Australianepiphytic orchids whose pollinators are confirmed, 9 are pollinated by sting-less bees (3).Partamona grandipennispollinates the monoecious herbBegoniainvolucra in Costa Rica (5).Trigona spinipespollinatesNymphaea amplainBrazil (103), andTrigonasp. pollinatesOndinea purpureain Australia (133).

Illegitimate use of flowers by stingless bees in which they remove resourceswithout pollinating, with or without damaging the flowers, occurs in both naturalhabitats (124) and agroecosystems (4, 132).

Although many species of stingless bees adapt to artificial nest sites, naturalvegetation can influence abundance of stingless bees. Abundance ofTrigonacarbonariain orchards of macadamia is correlated with extent of surroundingnatural eucalyptus vegetation (48). All surveyed chayote fields in Costa RicahadTrigonabees present, except for two fields with no surrounding forest for1 km (161). The abundance ofTrigonabees on longan flowers in a large orchardwas found to decrease with distance from an adjoining forest (20). Stinglessbees were common visitors to flowers of cupua¸cu growing near primary forestin Amazonian Brazil but were absent in disturbed habitats, which suggests thatbee populations are dependent on the primary forest (153).

Flight range is a function of worker bee size (78, 89) and possibly also colonypopulation size (141). The actual foraging distance also depends on the attrac-tiveness of the resource in relation to distance from the nest, needs of the colony,and availability of alternative resources. Using a mark-release technique, themaximum flight range ofCephalotrigona capitataandMelipona panamicaintropical forest was estimated to be 1.5 and 2.1 km, respectively (127). Captured

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 187

workers ofMelipona fuliginosareturned when released from distances of 2 kmfrom their nests (159). By training workers to an artificial nectar source andprogressively moving the source away from the hive, the maximum flight rangeof Plebeia mosquito, Trigona ruficrus, andTrigona amaltheawas 540, 840,and 980 m, respectively (65). Using a similar technique, the maximum flightrange of four species of stingless bees was from 120 to 680 m and was closelycorrelated with head capsule width (151a).

Using the calculated flight speed, the actual flight distances (rather than themaximum range) ofTrigona minangkabauwas estimated to be between 84and 434 m (58). Most of the nectar and pollen in the reserves of colonies ofPlebeia remotacame from plants growing within 100 m of their colonies (109).Trigona erythrogasterforaged on oil palms in a plantation 1.1 km from theforest they inhabited (8). The abundance ofTrigonasp. in a longan orchard innorthern Thailand was high at distances of 50 and 200 m from adjoining forestbut decreased greatly at 2.5 and 4 km from the forest (20).

The flight activity of colonies of stingless bees depends on species, populationof colonies, and availability of resources. The estimated 10,000 workers of a hiveof T. carbonariamade about 20,000 flights per day (49). Colonies ofTrigonaitami, Trigona moorei, andT. minangkabauwith populations of∼5000, 2000,and 2600 made about 7000, 2400, and 1200 flights per day, respectively (58).A newly established hive ofT. minangkabauwith only 350 workers made onlyabout 700 flights per day, showing the strong positive relationship between hivepopulation and flight activity (63).

The ability of guards at the hive entrance to recognize nestmates and ejectnon-nestmates is relevant to a situation where hives may be maintained at highdensities for crop pollination.T. minangkabaushows a very well-developedability to do this (144). Workers ofMelipona quadrifasciata, Meliponarufiventris, andMelipona scutellarisattacked 74, 60, and 14% of non-nestmateconspecifics encountered (23).

The potential of stingless bees for crop pollination is enhanced by the abil-ity to transfer colonies into artificial hives. These hives can be propagated(45, 91, 125) so that growers do not need to rely on natural populations. Hivescan also be transported where needed for pollination or for hive strengthening.Hives may be opened for extraction of honey, inspection, feeding, or requeeningif necessary and for treatment against natural enemies. The history of traditionalstingless beekeeping was reviewed recently (29).

CROP POLLINATION

More than 1000 plant species are cultivated in the tropics for food, beverages,fiber, spices, and medicines (104, 105, 118, 125). The breeding system and pol-linators of many of these crops have been catalogued (37, 125). Nearly half of

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

188 HEARD

the species of economically significant tropical crops originated in areas wherehoney bee species do not occur naturally, i.e. the neotropics, South Pacific, andAustralia. Approximately half of these plants are pollinated by bees (125). Manyof these∼250 species may be adapted to pollination by stingless bees.

All crops recorded as having been visited by stingless bees are reviewedhere. They are divided into sections depending on the importance of the bees.This division is preliminary, as information is lacking for many crop species.Difficulties in assessment included the lack of information on the need forpollination, e.g. the need for pollination of most mango varieties is unknown,and geographic variability, e.g. stingless bees are visitors to flowers of cropspecies in many parts of India but not in the Punjab, which is outside of theirgeographic range (13).

Crops Visited and Pollinated by Stingless BeesIn this section, I include crop species for which stingless bees make a provenand substantial contribution to pollination (Table 1).

MACADAMIA, MACADAMIA INTEGRIFOLIA(PROTEACEAE) Yields of macadamiabenefit from bee visitation (46), and low bee populations in many orchardsmay limit yield and quality (156). The major visitors to flowers are honey beesin Hawaii (149) and both honey bees andTrigonaspp. in Australia (48) andCosta Rica (74). Individuals of both species showed fidelity to the crop (154).No preference was shown by either honey bees or stingless bees for heavilyversus lightly flowering trees. Both bee species, but particularly stingless bees,preferred sunny outer racemes to inner shaded ones. Both bee species werepresent for the entire macadamia flowering season. Stingless bees foraged for amean of 7 h per day, compared with 10 h for honey bees. Populations ofTrigonabees, but not honey bees, were positively correlated to the extent of the absenceof surrounding natural eucalyptus vegetation in 5 out of 15 surveyed orchards,where>90% of surrounding vegetation was cleared (48). Honey bees collectedmainly nectar, and stingless bees mainly pollen, bringing the latter into closercontact with the stigma, a small surface on top of the style on which the pollengrain germinates, resulting in fertilization of the flower. Close contact with thestigma results in pollen grain deposition. Only 24% of the honey bees returningto hives in a macadamia orchard had been foraging on macadamia, comparedwith 100% ofTrigona bees (44).Trigona bees were opportunistic foragers,exploiting the temporary abundance of macadamia pollen by increasing colonyactivity (155). Racemes that were enclosed in cages that excluded honey beesbut allowed visitation by the smaller stingless bees yielded a nut set equal tothat on open pollinated racemes, which shows that stingless bees were efficientpollinators (47).

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 189

Table 1 Crops visited and at least occasionally or partially pollinated by stingless bees

Common name Name Family Reference

Crops for which stingless bees make an important contribution to pollinationMacadamia Macadamia integrifolia Proteaceae See textChayote, Choko Sechium edule Cucurbitaceae See textCoconut Cocos nucifera Arecaceae See textMango Mangifera indica Anacardiaceae See textCarambola Averrhoa carambola Oxalidaceae See textCamu-Camu Myrciaria dubia Myrtaceae See textMapati, Uvilla, Amazon Pourouma cecropiaefolia Moraceae See textTree GrapeAnnatto, Achiote Bixa orellana Bixaceae See textCupuacu Theobroma grandiflorum Sterculiaceae See text

Crops visited and occasionally or partially pollinated by stingless beesOnion Allium cepa Alliaceae See textStrawberry Fragaria chiloensis Rosaceae See text

X ananassaLoquat Eriobotrya japonica Rosaceae 109Peach Prunus persica Rosaceae. 27Plum Prunus domestica Rosaceae 20Pear Pyrus communis Rosaceae 20Coffee Coffea spp. Rubiaceae See textGuava Psidium guajava Myrtaceae See textJaboticaba Myrciaria cauliflora Myrtaceae 43Jambolan Syzygium cumini Myrtaceae 34Rose Apple Syzygium jambos Myrtaceae 27, 53, 56Sunflower Helianthus annuus Asteraceae See textNiger Guizotia abyssinica Asteraceae 114Litchi, Lychee Litchi chinensis Sapindaceae See textLongan Euphoria longan Sapindaceae 20Rambutan Nephelium lappaceum Sapindaceae See textSoap-Nut Sapindus emarginatus Sapindaceae See textAckee Blighia sapida Sapindaceae 69Guarana Paullinia cupana Sapindaceae 102Squash Cucurbita pepo Cucurbitaceae See textBitter Gourd Momordica charantia Cucurbitaceae 34, 141Watermelon Citrullus lanatus Cucurbitaceae 16, 80Cucumber Cucumis sativus Cucurbitaceae 16Luffa Luffa acutangula Cucurbitaceae 16Indian Jujube Zizyphus mauritiana Rhamnaceae 107Peach Palm, Pejibaye Bactris gasipaes Arecaceae 84Sago Palm Metroxylon sagu Arecaceae 150Rattan Calamus spp. Arecaceae 18, 68Breadfruit Artocarpus altilis Moraceae See textJackfruit Artocarpus heterophyllus Moraceae See textIce Cream Bean, Sipo, Inga edulis Leg.: Mimosoideae 1, 2

Guamo

(Continued )

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

190 HEARD

Leucaena Leucaena leucocephala Leg.: Mimosoideae 56Stylo, Brazilian Lucerne Stylosanthes guianensis Leg.: Papilionoideae 98Indigofera Indigofera endocaphylla Leg.: Papilionoideae See textPigeon Pea Cajanus cajan Leg.: Papilionoideae See textTamarind Tamarindus indica Leg.: Caesalpinioideae 141Hogplum Spondias mombin Anacardiaceae 1, 69, 141,

142Citrus Citrus spp. Rutaceae See textFennel Foeniculum vulgare Apiaceae 56Coriander Coriander sativum Apiaceae See textField Mustard Brassica campestris Brassicaceae 60Castor Oil Ricinus communis Euphorbiaceae 27, 34, 53Bellyache Bush Jatropha gossypifolia Euphorbiaceae See textRubber Hevea brasiliensis Euphorbiaceae See textSweet Pepper, Capsicum annuum varieties Solanaceae See text

Capsicum, ChiliEggplant Solanum melongena Solanaceae See textSesame Sesamum indicum Pedaliaceae See textIndian Shot Canna indica Cannaceae See textMembrillo Gustavia superba Lecythidaeae See textKapok Ceiba pentandra Bombacaceae 69Avocado Persea americana Lauraceae See textMonsterio Monstera deliciosa Araceae 111Cardamom Elettaria cardamomum ZingiberaceaeSaren Amomum villosum Zingiberaceae See textNanche, Murici Byrsonima crassifolia Malpighiaceae See textAcerola, Barbados Malpighia punicifolia Malpighiaceae See textCherrySisal Agave sisalana Agavaceae See textWhite Jute Corchorus capsularis Tiliaceae 53Panama Hat Plant Carludovica palmata Cyclanthaceae See text

Table 1

Common name Name Family Reference

(Continued )

See text

CHAYOTE, CHOKO,SECHIUM EDULE(CUCURBITACEAE) The vines that producethe subtropical vegetable chayote are monoecious, producing both male andfemale flowers on all plants. The plant is considered a good source of nec-tar for honey bees in the United States (77). In Costa Rica, many species ofbees and wasps visited chayote flowers, but the only important ones, on thebasis of abundance and efficiency, were 28 species of stingless bees. Of thesespecies,Trigona corvinaandPartamona cupirawere particularly important.Flowers covered with bags produced no fruits. Those open and visited by stin-gless bees produced fruit. Those open and visited by other bees and waspsproduced fruit but in reduced quantities. Furthermore, two fields of chayote in

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 191

areas with no surrounding trees and hence no stingless bees did not bear fruit(161).

COCONUT,COCOS NUCIFERA(ARECACEAE) Insect pollination is important forhigh yield of coconut (54). Honey bees,Apisspp., have been recorded on co-conut flowers in Hawaii, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Trinidad, Ecuador(37), and Fiji (77). Stingless bees, bothMeliponaspp. and others, are the dom-inant visitors in Costa Rica (51) and Surinam (34). In Trinidad, coconut pollenwas occasionally collected by four species of stingless bees but was much moreheavily collected by honey bees (141). Wasps, ants, earwigs, flies (37), butter-flies, and beetles (51) have also been recorded but are not considered effectivepollinators. Stingless bees visit both male and female flowers (51). Most (83%)individuals visiting pistillate flowers in search of nectar carried loads of coconutpollen from previously visited staminate flowers. Many of these (33%) then vis-ited staminate flowers on the same inflorescence. This behavior is conduciveto efficient pollen grain transfer. Yields are higher where hives of honey beesare kept in plantations (77). Thus, there is evidence that both honey bees andstingless bees contribute to the pollination this crop.

MANGO, MANGIFERA INDICA (ANACARDIACEAE) Visits by insects increaseyields of mango (38). The flowers are unspecialized, allowing pollination bymost visiting insects. Stingless bees are the most common insects visiting mangoflowers in studies in Brazil (27, 60, 139), India (140), and Australia (7). Pollenof mango was found in pollen stores of hives ofTrigona angustulain Chiapas(142). In Australia,Trigonabees were the most efficient pollinators on the basisof the proportions of flowers pollinated after a visit. This efficiency is due to thelarge amount of pollen carried on their bodies and the close contact they madewith the stigma. Furthermore,Trigonabees moved more frequently from tree totree and thus were probably the most effective cross pollinators (7). Honey beesare not strongly attracted to mango flowers and are only occasionally observed(37, 77). Flies are the most common visitors to mango flowers in many parts ofthe tropics (37) and are probably also efficient pollinators. Thus, stingless beesand flies are the most important pollinators of this crop.

CARAMBOLA, AVERRHOA CARAMBOLA(OXALIDACEAE) The distylous flowers ofcarambola require cross pollination to achieve fruit yield (37).M. favosahavebeen recorded visiting the flowers of carambola in Surinam (34). Large num-bers of two bee species,Trigona thoracicaandApis ceranavisited flowers ofcarambola in orchards in Malaysia. Both bee species carried large numbersof pollen grains on their bodies.T. thoracicawas an efficient pollinator, withhundreds of successfully germinated pollen grains deposited on flowers thatwere bagged and then exposed to one bee visit. Control flowers left bagged

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

192 HEARD

had a mean of six pollen grains that did not germinate.T. thoracicamade moreintermorph visits thanA. cerana. A. ceranastill appeared to be useful, however,because the introduction of hives into two orchards correlated with increasedyields (100).

CAMU-CAMU, MYRCIARIA DUBIA(MYRTACEAE) Insects are needed to pollinatethe protogynous flowers camu-camu. Although wind may effect some pollina-tion, bees are the most important pollinators and are attracted by the fragranceand nectar of the flowers. The most common visitors to camu-camu in Ama-zonian Peru wereMelipona sp. andScaptotrigona postica(99). Pollinationby bees, particularly Meliponini, is the dominant pollination system in theMyrtoideae (71), and hence, the importance of stingless bees in the pollinationof Myrtaceae may be greater than current records indicate.

MAPATI, UVILLA, AMAZON TREE GRAPE, POUROUMA CECROPIAEFOLIA

(MORACEAE) Stingless bees and ants were the only visitors to flowers of ma-pati in the Manaus region of Brazil (35). The ants did not carry pollen ontheir bodies nor move frequently between trees. The bees visited the flowersfrequently and carried many pollen grains on their legs and bodies. Activitywas greatest in the morning, when bees first visited the male flowers collectingpollen and then rapidly visited the female flowers. Bagged flowers did not setfruit, but pollination was not limiting because of the many bees attracted to theflowers and their effective pollinator behavior (35).

ANNATTO, ACHIOTE, BIXA ORELLANA (BIXACEAE) Annatto is efficiently buzzpollinated by large bees including the stingless beeMelipona melanoventer.The non–buzz pollinating speciesApis melliferaandTrigona spp. collectedpollen in a manner that achieved little pollination (75). This plant is stated tobe almost exclusively pollinated byM. fuliginosain many regions (159). Thepollen of annatto was found in the honey stores of hives ofH. pothieriin the IvoryCoast (69). The pollen of annatto was one of the most common found on the legsof workers ofMelipona seminigra merrillaeentering their hive in Amazonas (2).Pollen of this species was also found in a hive ofM. rufiventrisin Amazonas (1).

CUPUACU, THEOBROMA GRANDIFLORUM(STERCULIACEAE) Near Belem, flow-ers of the cupua¸cu fruit tree are visited by stingless bees, especiallyPlebeiaminima, and small weevils. Most plants were self incompatible, and the behav-ior of the bee was more conducive to out-crossing than that of the weevil. Theweevils, but not the bees, were present in a plantation in a disturbed habitat,suggesting that the bees depend on primary forest (153). Visitors to flowersof this plant in a forest area near Manaus included the stingless beesTrigonaclavipes(referred to asTetragona clavipes) andTrigona lurida (referred to as

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 193

Ptilotrigona lurida). The former bee only robbed pollen, butT. luridaappearedto be an effective pollinator (138).

Crops Visited and Occasionally or Partially Pollinatedby Stingless BeesIncluded in this section are crops that are recorded as having been visited orpollinated by stingless bees but where pollinator effectiveness is not determined.Also included are crops that are usually pollinated by other means but at sometimes or in some locations are pollinated by stingless bees. Table 1 includes allcrop species for which records exist. Where the record is a simple observationof use of a crop species, they are listed in Table 1 but not discussed in the text.

ONION,ALLIUM CEPA(ALLIACEAE) Seed crops of onion benefit from insect vis-itation. A review of world studies shows that various species of bees and fliesare the most common flower visitors (37). Honey bees andTrigona iridipenniswere shown to be the most important pollinators in India (113, 137). In a studyin Maharastra State in India, hives ofT. iridipennisandApisspp. were intro-duced to an experimental farm.T. iridipennisaccounted for almost half of allvisits to onion flowers, withA. ceranaandApis floreaaccounting for most ofthe remainder. All species foraged throughout the day. TheApisspp. visited ap-proximately twice as many flowers per minute thanT. iridipennis. T. iridipennisactively collected both nectar and pollen, while theApisspp. actively collectedonly nectar and incidentally collected pollen as a result. Although bee visitationwas shown to increase seed set, the relative pollinator efficiency of the three beespecies was not determined (81). Honey bees and stingless bees were the mostcommon insects visiting onion flowers in Brazil (6, 70). The stingless bees didnot pollinate as efficiently asApisspp., but they were still important (70).

STRAWBERRY, FRAGARIA CHILOENSISX ANANASSA(ROSACEAE) Imported stin-gless bees have been evaluated in Japan for pollination of strawberries inglasshouses. Colonies ofT. minangkabaufrom Sumatra and honey bees bothefficiently pollinated flowers. The number of flowers visited per 10 min wasestimated to be 7.7 for honey bees and 3.1 forT. minangkabau. A single honeybee visit to a flower pollinated 11% of achenes, while aT. minangkabauvisitpollinated 4.7%. To produce high quality fruits, 11 honey bee visits or 30T. minangkabauvisits are required per flower. Foraging byT. minangkabauwasmore suited to the confined glasshouse space than that of the honey bees (63).The Brazilian stingless beeNannotrigona testaceicorniswas also introduced inJapan to pollinate strawberries in glasshouses and proved to be efficient, withflowers that received four visits producing well-formed fruits (72). Althoughstrawberries can be pollinated by stingless bees, most production is in temperateareas, and other bees and flies are also efficient (37).

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

194 HEARD

COFFEE, COFFEA SPP. (RUBIACEAE) Honey bees and stingless bees visitedCoffea arabicaflowers in Brazil (92). The larger honey bees andMeliponaspp. were perhaps more efficient pollinators than the smaller species of sting-less bees. In highland central America,Trigona nigerrima, Trigona fulviventris,andT. angustulawere the most common stingless bee visitors of the flowers(126). In Chiapas, Mexico,T. angustulaare common visitors (142). In PapuaNew Guinea,Trigonaspp. were the most abundant visitors on heavily flower-ing Coffea canephoraplants but were absent from isolated flowering plants anddid not move as regularly as a leaf cutter bee,Creightonella frontalis, whichwas considered to be the best candidate for pollen grain transfer (162). InJava,C. canephorais visited by manyTrigona sp. (referred to asMeliponasp.) and other insects includingXylocopabees (53). Honey bees are the mostcommon visitors to coffee flowers in East Africa and Jamaica, and growers arerecommended to keep hives in their plantations (37).

GUAVA, PSIDIUM GUAJAVA, AND OTHER MYRTACEOUS CROPS (MYRTACEAE)

Stingless bees were observed to collect pollen of guava in Guatemala, CostaRica, and Equador but not the Dominican Republic (52), where stingless beesdo not occur.A. melliferaand bees of the generaBombus, Lassioglossum, andXylocopaalso collected pollen from guava flowers. In a study of the pollenreturned to the hive by four species of stingless bees in Trinidad, the pollenof guava was collected by all species and was the most commonly collectedpollen by all but one species; it was only occasionally collected by honey bees(141). Guava pollen was found in the pollen stores of hives ofH. pothieri inthe Ivory Coast (69). Guava pollen was found in the hives of honey bees andof 4 of the 10 species of stingless bees included in a study in a garden in Brazil(56). Large quantities of pollen,>10% of the total, of guava were found in boththe honey and pollen pots of hives ofMelipona marginata marginatain Brazil(67). Also in Brazil, pollen of guava was found in the honey and pollen stores ofM. quadrifasciata(43) andT. spinipes(28). The importance of insects in polli-nation of guava and the role of the various visitors requires study. Jaboticaba,jambolan, and rose apple are also visited by stingless bees (Table 1), but theirimportance and efficacy as pollinators are unknown.

SUNFLOWER,HELIANTHUS ANNUUS(ASTERACEAE) Near Sao Paulo in Brazil,sunflowers were visited byF. schrottkyi(27) andT. spinipes, Trigona hyalinata,andGeotrigonasp. (85). In India, sunflower is also attractive to all theApisspp. andT. iridipennis(40). Also in India, the potential ofT. iridipennisasa pollinator was tested by enclosing sunflower plants in cages. The yields inthose cages was higher than plants caged without bees but was not as high asopen pollinated plants (17). Stingless bees were recorded visiting sunflower

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 195

crops in Australia, but their low populations relative to those of honey beesled Radford et al to conclude that they have an insignificant role in pollination(106). Honey bees are usually the most abundant insects visiting sunflowers;however, locally abundant insects, particularly large solitary bees and bumblebees, may be important owing to their greater interest in collecting pollen (37).In tropical regions, stingless bees are sometimes common visitors to sunflowersbut are probably rarely important.

LITCHI, LYCHEE, LITCHI CHINENSIS(SAPINDACEAE) Stingless bees (identified asMeliponabut probablyTrigona sp.) and honey bees were the most commonvisitors to flowers of litchi in India in both Uttar Pradesh (96) and West Bengal(21).Trigonasp. (probablyT. carbonaria) was the most common species visit-ing flowers of litchi at one site in Australia but was absent at another site (66).Trigonabees collected pollen and nectar from litchi flowers but did not oftentouch the stigma. The larger honey bees usually touched the stigmas while vis-iting the flowers (66). More behavioral observations at other sites are requiredto determine if this is a common pattern on litchi flowers.

RAMBUTAN, NEPHELIUM LAPPACAUM(SAPINDACEAE) Bagged flowers of thisandrodioecious species set no fruit. Five species ofTrigona and A. ceranaare potential pollinators in East Kalimantan, Indonesia (148).T. thoracicaandtwo other species ofTrigona were among the most common insects visitingrambutan flowers in Peninsula Malaysia. None of the insects, including thestingless bees, foraging on hermaphrodite flowers carried rambutan pollen ontheir bodies, which suggests that they were not the pollinators (101).

SOAP-NUT, SAPINDUS EMARGINATUS(SAPINDACEAE) In Southern India, theflowers of the soap-nut tree were visited by a broad spectrum of insects, in-cludingApisspp.,Trigonasp., and other bees, wasps, flies, and butterflies. Thewasps and butterflies were considered to deliver more cross pollen, but bothcross and self pollination result in fruit set (115).

SQUASH, CUCURBITA PEPOAND OTHER CUCURBIT CROPS (CUCURBITACEAE)

Honey bees andT. spinipeswere the most common insects visiting flowers inBrazil (10). Squash bees of the generaPeponapisandXenoglossa(Anthophorini)rely solely on species ofCucurbitafor their pollen and most of their nectar. Theycoevolved with their hosts in Mexico, but it is often suggested they be intro-duced to other parts of the world forCucurbitapollination (146). However,honey bees, carpenter bees, bumble bees, halictid bees, and stingless bees areoccasionally important pollinators of squash (55). Bitter gourd, watermelon,cucumber, and luffa are visited by stingless bees (Table 1), but they are usuallyonly a small proportion of the complex of visitors (37).

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

196 HEARD

RATTAN, CALAMUSSPP. (ARECACEAE) The most important pollinating agents offour species ofCalamusin Thailand wereTrigonaspp. (18). In Malaysia,Trig-onaspp. were the most common insect, but nocturnal visitors were consideredmore important because pollen release occurs at night (68).

BREADFRUIT, ARTOCARPUS ALTILIS(MORACEAE) A breadfruit tree producesmale and female inflorescences alternately, so no self pollination can occur.Flowers are said to be wind pollinated, as they are odorless and have pow-dery pollen; hand pollination is practiced to increase fruit set (37, 105, 118). InBrazil,T. fulviventriscollected nectar in the morning and pollen in the afternoonfrom male inflorescences. They did not visit female inflorescences and there-fore did not effect pollination. They may have contributed to wind pollinationby dislodging pollen grains from the male flowers. This mode of insect-assistedwind pollination may explain why the plants produce nectar (22).

JACKFRUIT,ARTOCARPUS HETEROPHYLLUS(MORACEAE) Jackfruit has male andfemale inflorescences (37) and is considered to be insect pollinated on the basisof its scent and sticky pollen (105, 151).Trigonabees as well as drosophilidand phorid flies are attracted to the male and female flowers in Java (151). Inanother study, no visitors were observed to female flowers, and insect-assistedwind pollination is suggested (82).

LEGUMES (LEGUMINOSAE) Indigofera,Indigofera endocaphylla, is visited inIndonesia by a range of insects, mainly bees, includingTrigona itama. How-ever, the stingless bee was not common whereas the halictid beeNomia quadri-dentatawas a frequent and effective pollinator (9).A. ceranaand aTrigonasp.were the most common visitors to flowers of pigeon pea,Cajanus cajan, butthe former was considered the more effective pollinator (95). Records exist ofstingless bees visiting other legumes (Table 1). For many papilionoid legumes,the sexual column must be released from its concealed position within the petalsfor pollination to occur. This process, known as tripping, can only be performedby a bee of adequate weight, and hence smaller bees, such as many stinglessbees, are not effective pollinators.

CITRUS,CITRUSSPP. (RUTACEAE) Pollen ofCitrusspp. was rarely collected bytwo species ofMeliponaand honey bees but not byN. mellariaandT. nigra inTrinidad (141). Citrus pollen was found in the hives of honey bees and of 2 ofthe 10 species of stingless bees included in a study in a garden in Brazil (56).Scaura latitarsusandT. clavipeswere collected while visiting the flowers ofCitrussp. in Surinam (34).Citrus grandisand anotherCitrussp. were visitedby pollen-collectingTrigona (referred to asMeliponasp.) bees in Java (53).Evaluation of the importance of bees needs to account for the breeding system,as many citrus cultivars are parthenocarpic (135).

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 197

CORIANDER, CORIANDER SATIVUM(APIACEAE) Apis spp. andT. iridipenniswere the main pollinating insects of coriander near Pune, India.A. cerana,A. florea, andT. iridipennisvisited 14, 13, and 10 umbels (flower heads) perminute and 4, 3, and 2 plants per minute, respectively (136).

BELLYACHE BUSH, JATROPHA GOSSYPIFOLIA(EUPHORBIACEAE) Three speciesof stingless bees, particularlyP. mosquito, were considered the main pollinatorsof J. gossypifolia, a medicinal plant in Brazil (94).Trigonasp. was an importantpollinator in India (116).

SWEET PEPPER, CAPSICUM, CHILI,CAPSICUM ANNUUMVARIETIES (SOLANACEAE)

Wild bees and honey bees visitC. annuumflowers. The most common visitorsto these flowers in Brazil were the stingless beesT. angustulaand honey bees(37). In Java,Trigona sp. (referred to asMeliponasp.) collect pollen fromstamens and often climb to the top of stigmas, potentially transferring pollen(53). Roubik, however, stated that the smaller bees, including stingless bees,are probably not effective pollinators (125).

EGGPLANT, SOLANUM MELONGENA (SOLANACEAE) Trigona fulviventrisguianaehave been recorded visiting the flowers of eggplant (34). However,this species is buzz pollinated, and therefore,Trigonaspp. are unlikely to ef-fectively pollinate these plants (24).

SESAME, SESAMUM INDICUM (PEDALIACEAE) The stingless beesMeliponafulva, Trigona mazucatoi, T. lurida, T. williana, andC. capitatawere collectedfrom the flowers of sesame in Surinam (34). These authors noted that thesespecies were all larger stingless bees and could not explain the absence ofsmaller species.T. iridipennisvisited plots of sesame in India but were ob-served only on extrafloral nectaries (112).

INDIAN SHOT, CANNA INDICA(CANNACEAE) This crop is visited byTrigonasp.(referred to asMeliponasp.) in Java (53). The stingless bees forage deep inthe flowers collecting nectar and, in doing so, effect pollination.

MEMBRILLO, GUSTAVIA SUPERBA(LECYTHIDAEAE) Flowers of species of mem-brillo are pollinated by small- to medium-sized pollen-gathering bees suchasTrigona, Melipona, andBombus(102).Melipona fasciataheavily utilizedpollen ofG. superbain Panama (129).

AVOCADO, PERSEA AMERICANA(LAURACEAE) Small stingless bees are claimedto be good pollinators of avocado trees, though data are lacking (29, 152). InMexico and Guatemala,Geotrigona acapulconis, T. nigerrima, Partamonasp.,andScaptotrigonasp. are common visitors (DW Roubik, S Gazit & G Ish-Am,

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

198 HEARD

personal communication). Honey bees are efficient pollinators but are notstrongly attracted to the crop (59).

CARDAMOM, ELETTARIA CARDAMOMUM(ZINGIBERACEAE) In India, the honeybee,A. cerana, was the most common insect visiting cardamom collectingpollen in the morning and nectar in the afternoon. The stingless bee,T. iridipen-nis, was commonly observed collecting pollen. The pollen foragers made goodcontact with the anthers and stigma, which suggests they effectively pollinated(25a). In Papua New Guinea, stingless bees were not observed; instead thesolitary beeAmegilla sapiensefficiently pollinated the flowers (143).

SAREN, AMOMUM VILLOSUM (ZINGIBERACEAE) Saren, a valuable medicinalcrop, was visited byTrigona sp. (referred to asMelipona sp.) in Yunnan,giving a fruit set 4% higher than artificially pollinated plants and 29% higherthan open-pollinated controls (157).

NANCHE, BYRSONIMA CRASSIFOLIA, AND ACEROLA, MALPIGHIA PUNICIFOLIA

(MALPIGHIACEAE) Both nanche and acerola crops are visited and occasionallypollinated by stingless bees. However, specialist oil-collecting anthophorinebees are the main pollinators for bothB. crassifolia(12, 117) andM. punicifolia(73).

RUBBER, HEVEA BRASILIENSIS(EUPHORBIACEAE) Some stingless bees of thegenusTrigona collected pollen in India, where honey bees only visited ex-trafloral nectaries (61). In the New World, Ceratopogonidae flies are probablythe main pollinators (105).

SISAL, AGAVE SISALANA(AGAVACEAE) F. schrottkyiwas observed to visit sisalgrowing in a garden near Sao Paulo in Brazil (27). This species is mainlypollinated by bats at night and during the day by larger bees (125).

PANAMA HAT PLANT, CARLUDOVICA PALMATA(CYCLANTHACEAE) Flowers ofC. palmata, a crop plant, are visited and pollinated byTrigona sp. (referredto asMeliponasp.) and byA. indica in Java (53). In Panama,T. corvinaandT. fuscipennisare the common visitors (DW Roubik, personal communication).In the natural habitats ofC. palmatain Colombia, four species of stingless bees(all Trigona) pollinatedC. palmata(134). However in Amazonian Peru, smallweevils pollinated the flowers (41).

Crops Visited by Stingless Bees But Pollinatedby Other MeansRecords exist of visitation by stingless bees to the flowers of some crop speciesthat are known to be effectively pollinated only by other means (Table 2). Insome cases, stingless bees may have a negative impact by removing nectar or

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 199

Table 2 Crop species with records of visitation by stingless bees but known to be pollinated byother means

Pollinator or meansCommon name Name Family of fertilization Referencea

Papaya, papaw Carica papaya Caricaceae Sphingidae and other 11, 36, 53crepuscular mothsand butterflies

Custard apple, Annonaspp. Annonaceae Nitidulidae beetles 86cherimoya,atemoya,

Oil palm Elaeis guineensis Arecaceae Elaeidobiusspp. 42, 145(weevils)

Vanilla Vanilla spp. Orchidaceae Eulaemaspp. (bees) 32Cocoa, cacao Theobroma cacao Sterculiaceae Ceratopogonidae 163

midgesBrazil nut Bertholletia excelsa Lecythidaceae Large euglossine and 87, 102

carpenter beesMangosteen Garciniaspp. Clusiaceae Parthenocarpic 119, 120

and relativesBacuri Platonia insignis Clusiaceae Birds 76Benoil Moringa oleifera Moringaceae Xylocopaspp. (bees) 62Cashew Anacardium Anacardiaceae Bees and flies 39, 50

occidentaleLucerne, Medicago sativa Leguminosae: Large bees, e.g. 37

Alfalfa Papilionoideae megachilids,bumble bees

Sunn hemp Crotalaria juncea Leguminosae: Large bees e.g. 53, 90Papilionoideae Xylocopaspp.

Black pepper Piper nigrum Piperaceae Wind or rain 37Bananas Musaspp. Musaceae Parthenocarpic 105Passionfruit Passiflora edulis Passifloraceae Carpenter bees 26, 132Rape Brassica napus Brassicaceae Honey bees 4

var. oleifera

aReferences that demonstrate or review efficacy of pollinator.

pollen, making the flowers less attractive to the effective pollinator. In extremecases, stingless bees have a more obvious negative impact, such as damagingthe flowers of rape (4) or aggressively deterring the effective pollinators ofpassionfruit (132).

CONCLUSIONS

Stingless bees possess many characteristics that enhance their importance ascrop pollinators both as wild populations and managed pollinators. Character-istics of their social life (perenniality, polylecty, floral constancy, recruitment,harmlessness) suit them for pollination. Challenges to their widespread use

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

200 HEARD

include the lack of availability of large numbers of hives and the dearth ofknowledge of the pollination needs and major pollinators of tropical crops.

The absence of natural vegetation is associated with low local populations ofstingless bees, and hence forest clearing threatens the role of these insects in croppollination. The foraging flight range often is between 100 and 400 m. Henceremnant forests within this distance from orchards can provide adequate beepopulations. Improved domestication practices would increase hive availability,thereby reducing reliance on natural populations.

There are no crops known to be exclusively pollinated by stingless bees.Few generalizations can be drawn about the types of plants that they visit andpollinate. There are many crops in many families that, on the basis of oftenscanty knowledge, appear to benefit from pollination by these insects. Stin-gless bees are confirmed and important pollinators of annatto, camu-camu,chayote, coconut, cupua¸cu, carambola, macadamia, mango, and mapati. Theymake a contribution to the pollination of∼60 other crop species. They havebeen reported visiting∼20 crop species which are effectively pollinated byother means; these have been listed to refute the occasional false claims madeof the pollinator potential of stingless bees. Probably many other crops in thetropics are pollinated by stingless bees but have never been recorded in theliterature. It is clear that these bees provide economic benefits, by their croppollination services, that are substantial but not presently quantifiable. Sting-less bees display greater diet breadth and range of foraging behavior than honeybees, making them likely to be important to future development of pollinatorsbest suited to the needs of particular crops and habitats. I hope this review stim-ulates the necessary observation, experimentation, and publication to clarifythe importance of this abundant group of insects in world agriculture.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to David Roubik, Margaret Sedgley, Ben Oldroyd, Helen Wallace,and Tad Bartareau for many helpful comments on the manuscript.

Visit the Annual Reviews home pageathttp://www.AnnualReviews.org

Literature Cited

1. Absy ML, Camargo JMF, Kerr WE,de A Miranda IP. 1984. Esp´ecies deplantas visitadas por Meliponinae (Hy-menoptera; Apoidea), para coleta depolen na regi˜ao do medio Amazonas.Rev. Brasil. Biol.44:227–37

2. Absy ML, Kerr WE. 1977. Algumasplantas visitadas para obten¸cao de p´olen

por operarias deMelipona seminigramerrillae em Manaus.Acta Amazon.7:309–15

3. Adams PB, Lawson SD. 1993. Pollina-tion in Australian orchids: a critical as-sessment of the literature 1882–1992.Aust. J. Bot.41:553–75

4. Adegas JEB, Nogueira Couto RH.

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 201

1992. Entomophilous pollination in rape(Brassica napusL. var. oleifera) inBrazil. Apidologie23:203–9

5. Agren J, Schemske DW. 1991. Polli-nation by deceit in a neotropical mo-noecious herb,Begonia involucrata.Biotropica23:235–41

6. Alves SB, Vendramim JD, Silveira NetoS, Nakano O. 1982. Poliniza¸cao ento-mofila da cebolaAllium cepaL. Solo74:18–22

7. Anderson DL, Sedgley M, Short JRT,Allwood AJ. 1982. Insect pollination ofmango in Northern Australia.Aust. J.Agric. Res.33:541–48

8. Appanah S. 1982. Pollination of andro-dioecious Xerospermum intermediumRadlk. (Sapindaceae) in a rain forest.Biol. J. Linn. Soc.18:11–34

9. Atmowidjojo A-H, Adisoemarto S.1986. Potential pollen-transferring in-sects ofIndigoferaspp.Treubia29:225–35

10. Avila CJ, Martinho MR, de CamposJP. 1989. Poliniza¸cao e polinizadoresna produ¸cao de frutos e sementeshıbridas de abobora (Cucurbita pepovar.melopepo). Anais Soc. Entomol. Bras.18:13–19

11. Baker HG. 1976. “Mistake” pollinationas a reproductive system with specialreference to the Caricaceae. InTropicalTrees: Variation, Breeding and Conser-vation, ed. J Burley, BT Styles, pp. 161–69. London: Academic

12. Barros MAGe. 1992. Fenologia dafloracao, estrategias reprodutivas epolinizacao de especies simpatricas dogenero Byrsonima Rich. (Malpighi-aceae).Rev. Brasil. Biol.52:343–53

13. Batra SW. 1967. Crop pollination andthe flower relationships of the wild beesof Ludhiana, India.J. Kans. Entomol.Soc.40:164–77

14. Bawa KS. 1977. The reproductive bi-ology ofCupania guatemalensisRadlk.(Sapindaceae).Evolution31:52–63

15. Deleted in proof16. Bhambure CS. 1958. Further studies on

the importance of honey bees in the pol-lination of Cucurbetacea.Indian Bee J.20:10–12

17. Bichee SL, Sharma M. 1988. Effect ofdifferent modes of pollination in sun-flowerHelianthus annuusL. (Composi-tae) sown on different dates byTrigonairidipennisSmith.Apiacta23:65–68

18. Bogh A. 1996. The reproductive phe-nology and pollination biology of fourCalamus(Arecaceae) species in Thai-land.Principes40:5–15

19. Bohart GE. 1972. Management of wildbees for the pollination of crops.Annu.Rev. Entomol.17:287–312

20. Boonithee A, Juntawong N, PechhackerH, Huttinger E. 1991. Floral visits to se-lect crops by fourApisspecies andTrig-ona sp. in Thailand.Int. Symp. Pollin.,6th, Tilburg, Acta Hort.288:74–80

21. Brahmachary RL, Saha L, Mondal AK,Dasgupta P, Paul P. 1980.Apis floreaand dammar bees (Trigonidae): as thepollinating agents of certain fruit treesin Bengal.Proc. State-Level Sem. Bee-keep., West Bengal, pp. 63–66. WestBengal: Gobardanga Renaiss. Inst.

22. Brantjes NBM. 1981. Nectar and the pol-lination of bread fruit,Artocarpus altilis(Moraceae).Acta Bot. Neerl.30:345–52

23. Breed MD, Page RE J. 1991. Intra-and interspecific nestmate recognitionin Melipona workers (Hymenoptera:Apidae).J. Insect Behav.4:463–69

24. Buchmann SL. 1995. Pollen, anthers anddehiscence. InPollination of CultivatedPlants in the Tropics, ed. DW Roubik,pp. 121–23. Rome: Food Agric. Org.

25. Camacho E. 1966. Da˜no que las abe-jas jicotes del g´eneroTrigona causana los arboles de Macadamia.Turrialba16:193–94

25a. Chandran K, Rajan P, Joseph D, Surya-narayana MC. 1983. Studies on the roleof honeybees in the pollination of car-damom. Proc. Internatl Conf. Apicul-ture Tropical Climates, 2nd, New Delhi,1980, pp 497–504. New Delhi: IndianAgricultural Research Institute

26. Corbet SA, Willmer PG. 1980. Pollina-tion of the yellow passionfruit: nectar,pollen and carpenter bees.J. Agric. Sci.95:655–66

27. Cortopassi-Laurino M, Knoll FRN,Ribeiro MF, Heemert Cvan, Ruijter Ade.1991. Food plant preferences ofFrie-sella schrottkyi. Acta Hort.288:382–85

28. Cortopassi-Laurino M, Ramalho M.1988. Pollen harvest by AfricanizedApismellifera and Trigona spinipesin SaoPaulo botanical and ecological views.Apidologie19:1–23

29. Crane E. 1992. The past and present sta-tus of beekeeping with stingless bees.Bee World73:29–42

29a. da Silva MF. 1976. Insetos que visi-tam o ‘cupua¸cu’, Theobroma grandiflo-rum(Willd. ex Spring.) Schum. (Stercu-liaceae), e ´ındice de ataque nas folhas.Acta Amazon.6:49–54

30. DeGrandi-Hoffman G, Hoopingarner R,Klomparens K. 1986. Influence of honeybee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in-hive

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

202 HEARD

pollen transfer on cross-pollination andfruit set in apple.Environ. Entomol.15:723–25

31. Delfinado-Baker M, Baker EW, PhoonACG. 1989. Mites (Acari) associatedwith bees (Apidae) in Asia, with de-scription of a new species.Am. Bee J.129:609–13

32. Dressler RL. 1981.The Orchids. Cam-bridge: Harvard Univ. Press

33. Eickwort GC, Ginsberg HS. 1980. For-aging and mating behavior in Apoidea.Annu. Rev. Entomol.25:421–46

34. Engel MS, Dingemans-Bakels F. 1980.Nectar and pollen resources for sting-less bees (Meliponinae, Hymenoptera)in Surinam (South America).Apidolo-gie11:341–50

35. Falcao M A, Lleras E. 1980. Aspectosfenologicos, ecol´ogicos e de produtivi-dade do mapati (Pourouma cecropiifoliaMart.).Acta Amazon.10:711–24

36. Free JB. 1975. Observations on the pol-lination of papaya (Carica papayaL.) inJamaica.Trop. Agric.52:275–79

37. Free JB. 1993.Insect Pollination ofCrops. London: Academic

38. Free JB, Williams IH. 1976. Insectpollination of Anacardium occidentaleL., Mangifera indicaL., Blighia sap-ida Koenig andPersea americanaMill.Trop. Agric.53:125–39

39. Freitas BM, Paxton RJ. 1996. The role ofwind and insects in cashew (Anacardiumoccidentale) pollination in NE Brazil.J.Agric. Sci.126:319–26

40. Goel SC, Kumar A. 1981. Population ag-gregate ofMelipona iridipennisSmith(Apidae) on sunflower.Indian J. Hort.38:125–28

41. Gottsberger G. 1991. Pollination ofsome species of the Carludovicoideae,and remarks on the origin and evolutionof the Cyclanthaceae.Bot. Jahrb. Syst.Pflanzengesch. Pflanzengeogr.113:221–35

42. Greathead DJ. 1983. The multi-milliondollar weevil that pollinates oil palms.Antenna7:105–7

43. Guibu LS, Ramalho M, Kleinert-Giovannini A, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL.1988. Explora¸cao dos recursos floraispor colonias deMelipona quadrifasci-ata (Apidae, Meliponinae).Rev. Brasil.Biol. 48:299–305

44. Heard TA. 1987. Preliminary studies onthe role ofTrigonabees in the pollinationof macadamia.Proc. Aust. MacadamiaRes. Workshop, 2nd, Bangalow, ed. TTrochoulias, I Skinner, pp. 192-97. NewSouth Wales: Government Print.

45. Heard TA. 1988. Propagation of hivesof Trigona carbonaria Smith (Hy-menoptera: Apidae).J. Aust. Entomol.Soc.27:303–4

46. Heard TA. 1993. Pollinator require-ments and flowering patterns ofMaca-damia integrifolia. Aust. J. Bot.41:491–97

47. Heard TA. 1994. Behaviour and pollina-tor efficiency of stingless bees and honeybees on macadamia flowers.J. Apic. Res.33:191–98

48. Heard TA, Exley EM. 1994. Diversity,abundance, and distribution of insectvisitors to macadamia flowers.Environ.Entomol.23:91–100

49. Heard TA, Hendrikz JK. 1993. Factorsinfluencing flight activity of coloniesof the stingless beeTrigona carbonaria(Hymenoptera: Apidae).Aust. J. Zool.41:343–53

50. Heard TA, Vithanage V, Chacko EK.1990. Pollination biology of cashew inthe Northern Territory of Australia.Aust.J. Agric. Res.41:1101–14

51. Hedstr¨om I. 1986. Pollen carriers ofCo-cos nuciferaL. (Palmae) in Costa Ricaand Ecuador (Neotropical region).Rev.Biol. Trop.34:297–301

52. Hedstr¨om I. 1988. Pollen carriers andfruit development ofPsidium guajavaL.(Myrtaceae) in the Neotropical region.Rev. Biol. Trop.36:551–53

53. Heide F. 1923. Bloembestuiving inWest-Java.Meded. Alg. Proefstn. Land-bou14:20–37

54. Henderson A. 1988. Pollination biol-ogy of economically important palms.In The Palm-Tree of Life: Biology, Uti-lization and Conservation. Proc. Symp.Soc. Econ. Bot., New York, pp. 36–41.New York: NY Bot. Gard.

55. Hurd P. 1966. The pollination of pump-kins, gourds and squashes (genusCucur-bita). Proc. Int. Symp. Pollin. 2nd, Lon-don, Bee World Suppl.47:97–98

56. Imperatriz-Fonseca VL, Kleinert-Gio-vannini A, Ramalho M. 1989. Pollenharvest by eusocial bees in a non-naturalcommunity in Brazil.J. Trop. Ecol.5:239–42

57. Inoue T, Sakagami SF, Salmah S, Nuk-mal N. 1984. Discovery of successfulabsconding in the stingless beeTrigona(Tetragonula) laeviceps.J. Apic. Res.23:136–42

58. Inoue T, Salmah S, Abbas I, YusufE. 1985. Foraging behavior of indi-vidual workers and foraging dynamicsof colonies of three Sumatran stinglessbees.Res. Popul. Ecol.27:373–92

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 203

59. Ish-Am G, Eisikowitch D. 1993. Thebehaviour of honey bees (Apis mellif-era) visiting avocado (Persea ameri-cana) flowers and their contribution toits pollination. J. Apic. Res.32:175–86

60. Iwama S, Melhem TS. 1979. The pollenspectrum of the honey ofTetragoniscaangustula angustulaLatreille (Apidae,Meliponinae).Apidologie10:275–95

61. Jayarathnam K. 1970.Hevea brasilensisas a source of honey.J. Palynol.6:101–3

62. Jyothi PV, Atluri JB, Reddi CS. 1990.Pollination ecology ofMoringa oleifera(Moringaceae).Proc. Indian Acad. Scis.Plant Sci.100:32–42

63. Kakutani T, Inoue T, Tezuka T, MaetaY. 1993. Pollination of strawberry bythe stingless bee,Trigona minangkabau,and the honey bee,Apis mellifera: anexperimental study of fertilization effi-ciency.Res. Popul. Ecol.35:95–111

64. Kato M. 1996. Plant-pollinator interac-tions in the understory of a lowlandmixed dipterocarp forest in Sarawak.Am. J. Bot.83:732–43

65. Kerr WE. 1959. Biology of meliponidsVI Aspects of food gathering and pro-cessing in some stingless bees. InFoodGathering Behavior of Hymenoptera.Symp. Entomol. Soc. Am., pp. 24–31.Detroit: Entomol. Soc. Am.

66. King J, Exley EM, Vithanage V. 1988.Insect pollination for yield increases inlychee.Proc. Aust. Conf. Tree Nut Crops,4th, Lismore, ed. D Batten, pp. 142–45.Lismore: Exotic Fruit Grow. Assoc.

67. Kleinert-Giovannini A, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL. 1987. Aspects of thetrophic niche ofMelipona marginatamarginataLepeletier (Apidae, Melipon-inae).Apidologie18:69–100

68. Lee YF, Jong K, Swaine MD, Chey VK,Chung AYC. 1995. Pollination in the rat-tans Calamus subinermisand C. cae-sius (Palmae: Calamoideae).Sandaka-nia 6:15–39

69. Lobreau-Callen D, Thomas Ale,Darchen B, Darchen R. 1990. Quelquesfacteurs d´eterminant le comportementde butinage d’Hypotrigona pothieri(Trigonini) dans la v´egetation deCote-d’Ivoire.Apidologie21:69–83

70. Lorenzon MCA, Rodrigues AG, Des-ouza JRGC. 1993. Comportamentopolinizador deTrigona spinipes(Hy-menoptera, Apidae) na florada da ce-bola (Allium cepa L.) h´ıbrida. Pesq.Agropecu. Brasil.28:217–21

71. Lughadha EN, Proen¸ca C. 1996. A

survey of the reproductive biology of theMyrtoideae (Myrtaceae).Ann. Mo. Bot.Gard.83:480–503

72. Maeta Y, Tezuka T, Nadano H, SuzukiK. 1992. Utilization of the Brazilian stin-gless bee,Nannotrigona testaceicornis,as a pollinator of strawberries.HoneybeeSci.13:71–78

73. Magalhaes LMF, Oliveira Dde, OhashiOS. 1997. Pollination and pollen vec-tors in acerola,Malpighia punicifoliaL.In Pollination: from theory to practise,Proc. Int. Symp. Poll., 7th, Lethbridge,Acta Hort. 437:419–23

74. Mas´ıs CE, Lezama HJ. 1991. Estudiopreliminar sobre insectos polinizadoresde macadamia en Costa Rica.Turrialba41:520–23

75. Maues MM, Venturieri GC. 1995. Pol-lination biology of anatto and its polli-nators in Amazon area.Honeybee Sci.16:27–30

76. Maues MM, Venturieri GC. 1997. Pol-lination ecology of Platonia insignisMart. (Clusiaceae), a fruit tree fromeastern Amazon region. InPollination:From Theory to Practise, Proc. Int.Symp. Pollin., 7th, Lethbridge, Alberta,Canada, ed. KW Richards, pp. 255–59. Lethbridge, Alberta, Can.: Agric. &Agri-Food Can.

77. McGregor SE. 1976.Insect Pollinationof Cultivated Crop Plants, AgricultureHandbook No. 496. Washington, DC:US Dep. Agric.

78. Michener CD. 1974.The Social Behav-ior of the Bees. Cambridge, MA: Belk-nap, Harvard Univ. Press

79. Michener CD. 1990. Classification ofthe Apidae (Hymenoptera).Univ. Kans.Sci. Bull.54:75–164

80. Mohana Rao G, Suryanarayana MC.1988. Studies on pollination of wa-termelon [Citrullus lanatus (Thunb.)Mansf.].Indian Bee J.50:5–8

81. Mohanrao G, Lazar M. 1980. Studies onbee behaviour and pollination in onion.Khadigramodyog26:378–83

82. Moncur MW. 1985. Floral ontogeny ofthe jackfruit,Artocarpus heterophyllus.Aust. J. Bot.33:585–93

83. Montalvo AM, Ackerman JD. 1986.Relative pollinator effectiveness andevolution of floral traits inSpathiphyl-lum friedrichsthalii (Araceae).Am. J.Bot.73:1665–76

84. Mora Urp´ı J, Solıs EM. 1980. Po-linizacion en Bactris gasipaesH.B.K.(Palmae).Rev. Biol. Trop.28:153–74

85. Moreti AC CC, Marchini LC. 1992.Observacoes sobre as abelhas visitantes

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

204 HEARD

da cultura do girassol (Helianthus an-nuusL.) em Piracicaba, SP.Zootecnia30:21–27

86. Nadel H, Pe˜na JE. 1994. Identity, be-havior, and efficacy of nitidulid beetles(Coleoptera: Nitidulidae) pollinatingcommercialAnnonaspecies in Florida.Environ. Entomol.23:878–86

87. Nelson BW, Absy ML, Barbosa EM,Prance GT. 1985. Observations onflower visitors to Bertholletia excelsaH.B.K. andCouratari tenuicarpaA.C.Sm. (Lecythidaceae).Acta Amazon.15:225–34

88. Nieh JC, Roubik DW. 1995. A stinglessbee (Melipona panamica) indicates foodlocation without using a scent trail.Be-hav. Ecol. Sociobiol.37:63–70

89. Deleted in proof90. Nogueira-Couto RH, Costa JA, Silveira

RCM, Couto LA. 1992. Poliniza¸cao deCrotalaria junceapor abelhas nativas.Ecossistema17:12–16

91. Nogueira-Neto P. 1997.Vida e Criacaode Abelhas Indıgenas sem Ferrao. SaoPaulo: Ed. Nogueirapis

92. Nogueira-Neto P, Carvalho A, AntunesH. 1959. Efeito da exclus˜ao dos inse-tos pollinizadores na produ¸cao do cafebourbon.Bragantia18:441–68

93. Ormond WT, Pinheiro MCB, de CastellsARC. 1984. Contribui¸cao ao estudo dareproducao e biologia floral deJatrophagossypifolia L. (Euphorbiaceae).Rev.Brasil Biol. 44:159–67

94. O’Toole C. 1993. Diversity of nativebees and agroecosystems. InHymenop-tera and Biodiversity, ed. J LaSalle, IDGauld, pp. 169–96. Wallingford, UK:CAB Int.

95. Pande YD, Bandyopadhyay S. 1985.The foraging behaviour of honey beeson flowers of pigeon pea (Cajanus ca-jan) in Agartala, Tripura.Indian Bee J.47:13–15

96. Pandey RS, Yadava RPS. 1970. Polli-nation of litchi (Litchi chinensis) by in-sects with special reference to honeybees(Apisspp.) in India.J. Apic. Res.9:103–5

97. Parker FD, Batra SWT, Tepedino VJ.1987. New pollinators for our crops.Agric. Zool. Rev.2:279–304

98. Pereira-Noronha MR, Gottsberger I,Gottsberger G. 1982. Biologia floral deStylosanthes(Fabaceae) no serrado deBotacatu, estado de S˜ao Paulo.Rev.Brasil. Biol.42:595–605

99. Peters C, Vasquez A. 1986. Estudiosecologicos de camu-camu (Myrciariadubia) I. Produccion de frutas en pobla-

ciones naturales.Acta Amazon.16–17:161–74

100. Phoon A, Suhaimi A, Marshall A. 1984.The pollination of some Malaysianfruit trees. Simp. Biol. Kebangsaan,1st, Kebangsaan, pp. 87–111. SelangorMalaysia: Bangi

101. Phoon ACG. 1985. Pollination andfruit production of carambola,Aver-rhoa carambola, in Malaysia.Proc. Int.Conf. Apic. Trop. Climat., 3rd , Nairobi,Kenya, London: Int. Bee Res. Inst.

102. Prance GT. 1985. The pollination ofAmazonian plants. InKey Environ-ments: Amazonia, ed. GT Prance, TELovejoy, pp. 166–91. Cambridge: Perg-amon

103. Prance GT, Anderson AB. 1976. Stud-ies on the floral biology of neotropicalNymphaeaceae. 3.Acta Amazon.6:163–70

104. Purseglove J. 1968.Tropical Crops: Di-cotyledons. London: Longman

105. Purseglove J. 1972.Tropical Crops Mo-nocotyledons. London: Longman

106. Radford B, Nielsen R, Rhodes J. 1979.Agents of pollination in sunflower cropson the central Darling Downs, Queens-land. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. Anim. Husb.19:565–69

107. Rama Devi K, Atluri JB, Subba ReddiC. 1989. Pollination ecology ofZizyphusmauritiana(Rhamnaceae).Proc. IndianAcad. Sci. Plant Sci.99:223–39

108. Ramalho M, Giannini TC, Malagodi-braga KS, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL. 1994.Pollen harvest by stingless bee foragers(Hymenoptera, Apidae, Meliponinae).Grana33:239–44

109. Ramalho M, Imperatriz-Fonseca VL,Kleinert-Giovannini A, Cortopassi-Lau-rino M. 1985. Exploitation of floral re-sources byPlebeia remotaHolmberg(Apidae, Meliponinae).Apidologie16:307–29

110. Ramalho M, Kleinert-Giovannini A,Imperatriz-Fonseca VL. 1989. Utiliza-tion of floral resources by species ofMelipona(Apidae, Meliponinae): floralpreferences.Apidologie20:185–95

111. Ram´ırez BW, Gomez PL. 1978. Pro-duction of nectar and gums by flowersof Monstera deliciosa(Araceae) and ofsome species ofClusia(Guttiferae) col-lected by New WorldTrigonabees.Bre-nesia14–15:407–12

112. Rao GM, Lazar M, Suryanarayana MC.1981. Foraging behaviour of honeybeesin sesame (Sesamum indicumL.). IndianBee J.43:97–100

113. Rao GM, Suryanarayana MC. 1989.

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

CROP POLLINATION BY STINGLESS BEES 205

Effect of honey bee pollination on seedyield in onion (Allium cepaL.). IndianBee J.51:9–11

114. Rao GM, Suryanarayana MC. 1990.Studies on the foraging behaviour ofhoney bees and its effect on the seedyield in Niger.Indian Bee J.52:31–33

115. Reddi CS, Reddi EUB, Reddi NS,Reddi PS. 1983. Reproductive ecologyof Sapindus emarginatusVahl (Sapin-daceae).Proc. Indian Natl. Sci. Acad. B49:57–72

116. Reddi EUB, Reddi CS. 1983. Pollinationecology ofJatropha gossypiifolia(Eu-phorbiaceae).Proc. Indian Acad. Sci.Plant Sci.92:215–31

117. Rego MMC, de Albuquerque PMC.1989. Comportamento das abelhas vis-itantes de murici,Byrsonima crassifo-lia (L.) Kunth, Malpighiaceae.Bol. Mus.Para. Emilio Goeldi. Nova Ser. Zool.5:179–93

118. Rehm S, Espig G. 1991.The CultivatedPlants of the Tropics and Subtropics:Cultivation, Economic Value, Utiliza-tion. Weikersheim, Germany: JosephMargraf

119. Richards AJ. 1990. Studies inGarcinia,dioecious tropical forest trees: agamo-spermy.Bot. J. Linn. Soc.103:233–50

120. Richards AJ. 1990. Studies inGarcinia,dioecious tropical forest trees: the phe-nology, pollination biology and fertiliza-tion of G. hombronianaPierre.Bot. J.Linn. Soc.103:251–61

121. Richards KW. 1993. Non-Apis beesas crop pollinators.Rev. Suisse Zool.100:807–22

122. Roig-Alsina A, Michener CD. 1993.Studies of the phylogeny and classifi-cation of long-tongued bees (Hymenop-tera: Apoidea).Univ. Kans. Sci. Bull.55:124–62

123. Roubik DW. 1979. Africanized honeybees, stingless bees, and the structureof tropical plant-pollinator communi-ties.Proc. Int. Symp. Pollin. 4th, Mary-land, Md. Agric. Exp. Stn. Spec. Misc.Publ.1:403–17

124. Roubik DW. 1989.Ecology and Natu-ral History of Tropical Bees. Cambridge,UK: Cambridge Univ. Press

125. Roubik DW. 1995.Pollination of Culti-vated Plants in the Tropics. FAO Agric.Serv. Bull. No. 118. Rome, Italy: FoodAgric. Org.

126. Roubik DW. 1998. Coffee pollinationin Central American highlands: Africanbees and the reproduction of an autoga-mous shrub.Ecol. Lett.In Press

127. Roubik DW, Aluja M. 1983. Flight

ranges of Melipona and Trigona intropical forest.J. Kans. Entomol. Soc.56:217–22

128. Roubik DW, Moreno JE. 1990. Socialbees and palm trees: what do pollen di-ets tell us? InSocial Insects and the En-vironment: Proc. 11th Int. Congr. IUSSI,Bangalore India, ed. GK Veeresh, BMallik, CA Viraktamath, pp. 427–28.Leiden: EJ Brill

129. Roubik DW, Moreno JE, Vergara C,Wittmann D. 1986. Sporadic food com-petition with the African honey bee: pro-jected impact on neotropical social bees.J. Trop. Ecol.2:97–111

130. Sakagami SF. 1982. Stingless bees. InSocial Insects, ed. HR Hermann, 3:361–423. New York: Academic

131. Sakagami SF. 1971. Ethosoziologischervergleich zwischen honigbienen undstachellosen bienen.Zeit. Tierpsychol.28:337–50

132. Sazima I, Sazima M. 1989. Maman-gavas e irapu´as (Hymenoptera, Apoi-dea): visitas, intera¸caes e conseq¨uenciaspara poliniza¸cao do maracuj´a (Passiflo-raceae).Rev. Brasil. Entomol.33:109–18

133. Schneider E. 1983. Gross morphologyand floral biology ofOndinea purpureaden Hartog.Aust. J. Bot.31:371–82

134. Schremmer F. 1982. Bl¨uhverhaltenund best¨aubungsbiologie vonCarlu-dovica palmata (Cyclanthaceae)—einokologisches paradoxon.Plant Syst.Evol.140:95–107

135. Sedgley M, Griffin AR. 1989.SexualReproduction of Tree Crops. London:Academic

136. Shelar DG, Suryanarayana MC. 1981.Preliminary studies on pollination of co-riander (Coriandrum sativumL.). IndianBee J.43:110–11

137. Sihag RC. 1985. Floral biology, melit-tophily and pollination ecology of onioncrop. InRecent Advances in Pollen Re-search, ed. TM Varghese, pp. 277–84.New Delhi, India: Allied

138. Deleted in proof139. Simao S, Maranh˜ao ZC. 1959. Os in-

setos como agentes polinizadores damangeira.An. Esc. Super. Agric. “LuisDe Queiroz”16:299–304

140. Singh G. 1989. Insect pollinators ofmango and their role in fruit setting.ActaHort. 231:629–32

141. Sommeijer MJ, de Rooy GA, Punt W,de Bruijn LLM. 1983. A comparativestudy of foraging behavior and pollen re-sources of various stingless bees (Hym.,Meliponinae) and honeybees (Hym.,

P1: KKK/plb P2: ARS/KKK/plb QC: ARS/anil T1: KKK

November 4, 1998 11:18 Annual Reviews AR074-08

206 HEARD

Apinae) in Trinidad, West-Indies.Api-dologie14:205–24

142. Sosa-N´ajera MS, Mart´ınez-HernandezE, Lozano-Garc´ıa MS, Cuadriello-Aguilar JI. 1994. Nectaropolliniferoussources used byTrigona (Tetragonisca)angustulain Chiapas, southern Mexico.Grana33:225–30

143. Stone GN, Willmer PG. 1989. Pollina-tion of cardamon in Papua New Guinea.J. Apic. Res.28:228–37

144. Suka T, Inoue T. 1993. Nestmate Recog-nition of the Stingless BeeTrigona(Tetragonula) minangkabau(Apidae,Meliponinae).J. Ethol.11:141–47

145. Syed RA. 1979. Studies on oil palm pol-lination by insects.Bull. Entomol. Res.69:213–24

146. Tepedino VJ. 1981. The pollination effi-ciency of the squash bee (Peponapis pru-inosa) and the honey bee (Apis mellifera)on summer squash (Cucurbita pepo). J.Kans. Entomol. Soc.54:359–77

147. Torchio PF. 1987. Use of non-honey beespecies as pollinators of crops.Proc. En-tomol. Soc. Ont.118:111–24

148. Uji T. 1987. Penyerbukan pada rambutan(Nephelium lappaceumvar.lappaceum).Berita Biol.3:31–34

149. Urata U. 1954. Pollination requirementsof macadamia.Hawaii Agric. Exp. Stn.Tech. Bull.22:1–40

150. Utami N. 1986. Pollination in sago(Metroxylon sagu). Berita Biol. 3:229–31

151. van der Pijl L. 1953. On the flower biol-ogy of some plants from Java.Ann. Bo-gor. 1:77–99

151a. van Nieuwstadt MGL, Iraheta CER.1996. Relation between size and for-aging range in stingless bees (Apidae,Meliponinae).Apidologie27:219–28

152. Velthuis H. 1990. The biology and theeconomic value of the stingless bees,compared to the honey bees.Apiacta25:68–74

153. Venturieri GA, Pickersgill B, OveralWL. 1993. Floral biology of the Ama-zonian fruit tree “cupuassu” (Theo-broma grandiflorum). In Biodiversityand Environment—Brazilian Themes forthe Future, London, p. 23. London:Linn. Soc. London, R. Bot. Gard.

154. Vithanage V, Ironside DA. 1986. The in-sect pollinators of macadamia and theirrelative importance.J. Aust. Inst. Agric.Sci.52:155–60

155. Wallace H. 1994.Bees and the pollina-tion of macadamia. PhD thesis. Univ.Queensland

156. Wallace HM, Vithanage V, Exley EM.1996. The effect of supplementary pol-lination on nut set ofMacadamia(Pro-teaceae).Ann. Bot.78:765–73

157. Wang XZ, Chen YP, Gao XO, Xie JM.1981. The discovery ofMelipona sp.pollinating Amomum villosumLour. inYunnan Province.Yunnan Agric. Sci.Tech.5:49

158. Wille A. 1965. Las abejas atarr´a dela region mesoamericana del g´eneroy subgeneroTrigona (Apidae-Melipo-nini). Rev. Biol. Trop.13:271–91

159. Wille A. 1976. Las abejas jicotes delgeneroMelipona(Apidae: Meliponini)de Costa Rica.Rev. Biol. Trop.24:123–47

160. Wille A. 1983. Biology of the stinglessbees.Annu. Rev. Entomol.28:41–64

161. Wille A, Orozco E, Raabe C. 1983.Polinizacion del chayoteSechium edule(Jacq.) Swartz en Costa Rica.Rev. Biol.Trop.31:145–54

162. Willmer PG, Stone GN. 1989. Incidenceof entomophilous pollination of lowlandcoffee (Coffea canephora); the role ofleafcutter bees in Papua New Guinea.Entomol. Exp. Appl.50:113–24

163. Young AM. 1983. Nectar and pollenrobbing of Thunbergia grandiflorabyTrigona bees in Costa Rica.Biotropica15:78–80

Copyright of Annual Review of Entomology is the property of Annual Reviews Inc. and its content may not be

copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.