The Role of Vlah and Ist Rules on Athos and Sinai. Reflection on a Portrait of Constantin...

-

Upload

miu-alexandru -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

4

description

Transcript of The Role of Vlah and Ist Rules on Athos and Sinai. Reflection on a Portrait of Constantin...

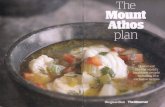

THE ROLE OF AND ITS RULERS ON ATHOS AND SINAI(Reflections on a Portrait of Constantin Brâncoveanu, Prince

of at St. Katherine's Monastery on Mt. Sinai)J. G. NANDRIS

(London)

In Post-Byzantine times, after the fall of Constantinople toSultan in 1453, the principalities of Moldavia and

Wallachia played a part out of all proportion to their size and resourcesin endowing and the monastic centres of eastern Orthodoxspirituality which now found themselves under Ottoman influence. Poli-tically they also filled the role of buffer states in Europe against otherwisesubstantially unopposed expansion of that influence, without gaining verymuch credit or external assistance the process. Artistically. this was theperiod during which the unique painted churches of Bukovina the northof were created. These are unique, not in that they do not haveintimate relationships with other masterpieces of Post-Byzantine art inSerbia and on Athos, but in that brilliant polychrome paintings werecarried out on the external as well as internal walls of the churches,for half a millennium they have retained their splendour in snow and rain.These buildings became carefully paradigms of Christian spiri-tuality, setting out visually. in the relationships between the different partsof the building, the tenets of faith of peasant people whose fervent beliefswere independent of literacy. Indeed it is often forgotten how of

a4vantage is illiteracy in the strengthening of traditional culture. Thedistinctive architecture of the Moldavian churches is reflected, by virtueof patronage of the Voivodes of Moldavia and Wallachia, in that ofvery many of the monastery churches of Athos. In recognition of theLatin or benefactors, they are depicted or mentioned portraitson the walls or in the frescoes, in heraldic carvings, inscriptions and dedi-cations of ikons, on the gilded covers of thrones and books, and in the parch-

chrysobulls with which they ratified their endowments to theteri. These further included gifts of estates in calledfrom which the monastery could continue to enjoy revenues. The source ofall these riches is often alluded to under terms obscure to most west Euro-peans, such as or even less comprehensibly - Uvgro-phaldaki a. But no other patrons can be adduced who so consistently andgenerously supported nearly every one of the twenty or so autonomousgreat monasteries of Athos, irrespective of their particular national affilia-tions then or at this time, especially in such matters as rebuilding afterthe frequent fires. and Simionescu (1979) have recently documentedthese benefactions. The concept of nationality remains in any an ana-

REV. SUD-EST EUROP., XIX. 3. BUCAREST, 1981

Romanian

maintaining

in

theirwhere

amuch

in

mentRomania,

-

case

605-610,

Wallachia,

Patih

in

an

monas-,

www.dacoromanica.ro

606 NANDRIS

chronistic one in Byzantine history for a very long time. It is perhapsironic that the only major Orthodox nation of south-east Europe notto have its monastery on Athos is the Romanian, whose decayingskete of Prodromul at the farthest tip of the peninsula is as large as manymonasteries, yet has consistently been denied that status.

One further feature of Athos should be mentioned, the presence ofa class of civilian monastery servants, employed on the estates, and incutting and transporting the timber from which an important part ofmonastery revenue from within the peninsula was derived. Prominentamong these servants were Vlahs, or the Latin-speaking inhabi-tants of mainland Greece, whose various specialised roles included mule-teering, and hence control of much of Balkan transport before the age ofthe railways. Themselves fervently Orthodox, though without prejudiceto their efficiency elsewhere as brigands (the "klephts" of the Greek Warof Independence), these people are ancient 'Thracian' inhabitaRts of theBalkan peninsula, who acquired Latinity from the Romans1980). their native mountain villages of the Pindus such as Metsovo orSamarina, their large, impressive take a quite different formfrom the Moldavian or Athonite type, and are visibly related to theRoman Basilica.

It is now being appreciated what an important role Orthodoxnite monasticism filled in the preservation for posterity of inestimablehistorical evidence, jealously guarded in its archives and treasuries despite

the vicissitudes which have destroyed so much more. andportraits are gradually being published, and for example Turdeanu (inRévue des 1?oumaines, drew attention to a portraitof a Wallachian ruler, Cantaeuzino, at the monastery ofAthos. It is often assumed that historical material which is known tofamiliar with the monasteries must already be more widely known.is not necessarily always the case, and it is better to draw attentionevidence than to lose sight of it. In this spirit I should like to refer toportrait of Constantin Brâncoveanu, which now hangs in Council Roomof the Monastery of St. Katherine on Mount Sinai, and use the occasiondraw out some analogies between the Athonite and the SinaiticIt is unpublished (Beza 1937 or Rabino 1938 e.g.), but needs toreconsidered.

The picture is in oils on canvas, framed, and in good condition..It depicts the Wallachian ruler of 1688-1714 in richly trimmedrobes, with a fine grasp of sartorial niceties and a less sure one oftive. The portrait is nevertheless a fine one, and approximately lifeHis is on the table, and is also found in slightly different form behindhim surmounting the arms of Wallachia. The inscription besidehead reads :

OVANTRAN

/ETIS 42.

J696.

The portrait is a clear likeness of Brâncoveanu. It can be comparedhis depiction in Romania, in the frescoes of the monastery of Hurezu f

3. 2

own

chnrches

all

Iviron

Thk

the

not

ermine

CONSTANTINVSSVPREMVS

Aromini,

their

Documents

1976) recently

be

perspec-

crown

www.dacoromanica.ro

3 THE ROLE OF VLAH" ON AND SINAI 607

example, which show him in similar ermine trimmed robes, with the samefeatures and beard, and the same ring with a stone on the little finger of

right hand. The Sinai picture seems to be the original, although thereis at least one version in Romania.

The presence of the portrait at St. Katherine's itself illustrates thatRomanian concern the support of Orthodox monasticism extended as

far afield as Sinai, a remote region under mediaeval conditions travel.There are considerable analogies between the relations of Romania or

to both Athos and Sinai, and between the historical roles of thetwo centres of monasticism. These arise in part out of the nature of Ortho-dox monasticism itself, whose spirituality and organisation lean especiallyheavily on its traditions, and in addition monks always travelledbetween the two centres. The location of the "real" Mount Sinai has beenmuch disputed, but is irrelevant before the fact that the Monastery ofSt. Katherine still stands where it was founded in the mid sixth centuryby Justinian, himself a native Latin-speaker of south-east Europe froma village near Skopje.

It was thus Christian monasticism which created and maintainedthis mountain and its surroundings as a holy place during the last oneand a half millennia. Even earlier, from the first one or two centuries A.D.,the early hermits made the desert their peculiar province, first in theThebaid and at Skete Egypt, and immediately thereafter inTo the monastery we the guardianship of the oldest library in theworld, including recently discovered further pages of the Codex Sinai-ticus and other treasures, and the preservation of the oldest continuously

ATHOS

his

of

have

in Sinai.owe

for

www.dacoromanica.ro

608 J. G. NANDRIS

inhabited building in the world, for us and our posterity. The analogy wthe Athonite libraries is clear, and while the oldest monastery thereGreat Lavra was founded later than Sinai in the tenth century, ontoo there were earlier hermits on the peninsula. Aside from this rolepreservation and transmission of objects and traditions, there are otherparallels between the two centres. Among its many metohia (whichas far-flung as India) Sinai was also given lands in Romania, where theseholdings gave its name to the town of Sinaia. It also had monasteryservants, originally assigned by Justinian soon after the foundation,man the fortified site which his envoys had built, and to protect themonks from the Saracens, or what we should now probably refer tothe local Bedouin.

It might be too much, to that there should be any furtherparallel between these soldier-servants, with their further role as cameldrivers and as guides for pilgrims to Sinai, and the muleteers andworkmen found on Athos. But it is precisely the case. These people todayhave become the Jebaliyeh tribe, meaning the Mountaineers, onemany Islamic Bedouin groups in Sinai, but distinguished from all theothers in many ways. They have a special role as servants of the monas-tery, and are settled immediately around it. They have tenacious tradi-tions as to origins from a land called from whence a hundredof them with their families were sent by Justinian, and joined by anothercontingent from Egypt. At that time they were Christians. These tradi-tions are substantiated not only by the writings of Byzantine chroniclers.such as Procopius (the coeval of Justinian) and of Eutychius (writingaround 900 A.D., and much better acquainted with the region thanProcopius) but also by scientific evidence. The latest serological evidenceshows that the blood-groupings of the Jebaliyeh are completely distinctive.among all other populations of the area. They are one of the oldest isolatesamong Near Eastern peoples, supporting the long-standing traditionthey go back 1,400 years. Only the Samaritans can a longer serolo-gical record of isolation, while there is no prospect that any other modernpopulation in the Near East can to trace older genetic links, withfor example the ancient Hebrew peoples. The Jebaliyeh blood groupsinclude traces of genes from Egyptian sources, substantiating the oraltradition of an Egyptian contingent.

The prospect of linking a part of their genetic component with somesouth-east European group cannot taken literally. It must be remem-bered that south-east European populations are not comparable isolateshaving been centred in regions of intensive historical ferment, whereathe Samaritans and the Jebaliyeh have both been protected by culturalexclusiveness from their neighbours, and in the case of the Jebaliyehby geographical isolation. But the fact remains that the most likely sourcewhich Justinian, the Latin-speaking native of an Empire whosetants he knew well, would have chosen a group suitable for the ofsoldiers guides, and - with the ultimate substitution of the camel forthe - as muleteers, were precisely the Latin-speaking natives ofsouth-east Europe. Like their descendants, the modern Vlahs of Greece(the Aromini), these were famed as from the time of the Romanor Byzantine armies, down to the modern Greek army in which they form

of

still

that

be

role

as

among

their

claim

claim

mule

www.dacoromanica.ro

THE ROLE OF VLAH" ON ATHOS SINAI

the toughest paratroopers. They traditionally fill all the relevant rolesof muleteers, monastery workmen, guides and so forth.

The geographical location in this context of remainsmatical, and is often equated with parts of modern Wallachia -a namewhich like Welsh, and a wide range of other derivative terms through-out Europe owes its origin to the same Germanic root, apparently usedby Celtic peoples to denote "strangers" across they came in thecourse of their expansion during the Iron Age across Europe. The En-glish Arabist Palmer in the nineteenth century records the Jebaliyehaccount of their origins from the land of "K'lah" - which is the resultof the Arabic disinclination to vocalise the letter "V". We knowthe record of the Armenian geographer Moses Khorenatzi, writing in theninth century about Sarmatia and Thrace, that by that time therein that region (including modern Romania) a geographical entity (andnot merely a people) known as - "the unknown land they callBalakh". The best reason for a land being obscurely known must surely-be if it were as mountainous and afforested as the Carpathians.shortly after this in Eutychius, writing around 900 A.D., we find a laco-nic and hitherto unremarked reference, in the passage where he is quiteunambiguously discussing the Jebaliyeh, and nobody else. He says :

; suntque ex ipsis Lachmienses". (There are also among them theLachmienses.) The Arabic context (and the fact that Eutychiushad Arab origins which give his knowledge of the region more authoritythan those of Procopius) again explains the loss of the initial "V", andmeans that in this enigmatic clause we surely have reference to the Vlahpeople. The historical tradition of the Jebaliyeh is firm that they camefrom by the Black Sea, and that they were Roman Byzantines,,initially speaking the Roman language. Latin was and remained the

language of Byzantium in any case until the time of Heraclius, inthe seventh century ; and for much longer the daily language of anportant proportion of the native inhabitants of the Empire. We nowknow that such natives, the Bessae, were represented among the monksof Sinai within decades of its foundation in the sixth century, as wellas in other Palestinian monastic centres.

The Jebaliyeh present us with an ethnoarchaeological and histo-rical problem which in its essentials refers to the fundamental issuewhat it is that constitutes the identity of a human group. The shortanswer would seem to be that it is "behaviour as if" that identity were afact ; and "obedience the often unenforceable" cultural norms whichsustain belief in it (Nandris, forthcoming). It certainly is not any single-factor explanation of genetic, linguistic or any other literalistThe transformations of Jebaliyeh culture to suit the Sinaitic environ-ment and to further their relations with neighbouring tribes (all of whom.they antedate) are among the features which make them a paradigm ofthe ethnoarchaeological problem. In the interest of survival they adoptedArabic, Islam, and all the ways of life appropriate to the desert. Yetagainst all probability they have not forgotten their origins. Theirconfreres in south-east Europe have made similar adjustments toindustrial or urban desert, and to their language of daily

609'

Very

himself

offi-cial

to

continuity..

whom

was

of

remotethe

www.dacoromanica.ro

W J. G. NANDRIS

The field work in Sinai in 1978 took place in the context of researchinto this ethnoarchaeological problem and was supported by the BritishAcademy. These reflections centred however distantly on the portrait

Constantin Brâncoveanu arise as a by-product of those researches. Theyare presented here in the conviction that we should not show

willing to overcome physical and intellectual obstacles linking remoteplaces and ideas than were those early south-east Europeans.

REFERENCES

M., 1937, Urine Bucharest.V., C., 1979, Witnesses Romanian Presence on Editura

Sport-Turism, Bucharest.Nandris, J. G., 1980, The Thracian Inheritance, "Illustrated London News", June 1980

99-101.Nandris, J. G., forthcoming, The Jebaligeh Sinai, and Land of Pro-

ceedings; Wellkongress fur Thrakologie (Vienna, June 1980).M., 1938, Le de du Sinai, Cairo (Royal Automobil

Club of Egypt).

6

ourselves

Beza, Rdsdritul

www.dacoromanica.ro