The role of CSR motives and CSR fit

Transcript of The role of CSR motives and CSR fit

Master's Thesis

Communication and Information Sciences

Specialization: Business Communication and Digital Media

Faculty of Humanities

Tilburg University, Tilburg

The role of CSR motives and CSR fit

in stakeholders’ intentions of spreading eWOM

Anna Shemetkova

ANR 268079

Supervisor: Jos Bartels

Second reader: Sarah van der Land

July 2017

2

Abstract

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication in social media is becoming more

important for companies today. Consumers can not only gain any information about an

organization they want, but also share their own opinion about it and spread electronic word-of-

mouth (eWOM). The main goal of this study was to investigate the impact of communicated

CSR motives and CSR fit on stakeholders’ intentions of spreading eWOM and the role of

identity attractiveness and message credibility in this relations. An experiment with 2 x 2

between-subject design was conducted. Results showed that for consumers there is no difference

between egoistic and values-driven CSR motives and high or low CSR fit in the context of

eWOM intentions. This study contributes to the contemporary literature regarding CSR

communication and has practical implication for companies.

3

Contents

Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ 2

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 4

2. Theoretical framework ................................................................................................................ 6

2.1. CSR motives ......................................................................................................................... 6

2.2. CSR fit .................................................................................................................................. 7

2.3. eWOM, CSR motives and CSR fit ....................................................................................... 8

2.3.1. eWOM ........................................................................................................................... 8

2.3.2. Interaction of eWOM, CSR motives and CSR fit ......................................................... 9

2.4. Identity attractiveness ......................................................................................................... 10

2.5. Message credibility ............................................................................................................. 12

3. Methods ..................................................................................................................................... 14

3.1. Design ................................................................................................................................. 14

3.2. Procedure ............................................................................................................................ 14

3.3. Participants ......................................................................................................................... 14

3.4. Stimulus material ................................................................................................................ 15

3.5. Instrumentation/Variables .................................................................................................. 16

4. Results ....................................................................................................................................... 19

4.1 Manipulation check ............................................................................................................. 19

4.2 Hypothesis check ................................................................................................................. 19

4.3 Additional analysis .............................................................................................................. 22

5. Discussion & Conclusion .......................................................................................................... 26

5.1. Findings .............................................................................................................................. 26

5.2. Practical implications ......................................................................................................... 32

5.3. Limitations and future research .......................................................................................... 33

5.4. Conclusion .......................................................................................................................... 35

6. References ................................................................................................................................. 36

Appendix A Questionnaire ............................................................................................................ 41

Appendix B Scenarios ................................................................................................................... 47

Appendix C Operationalization table ............................................................................................ 49

4

1. Introduction

Nowadays more and more companies are involved in corporate social responsibility

(CSR) activities, for example, philanthropy, socially responsible employment, programs that

support minorities (Drumright, 1994) or environmental issues (Dahlsrud, 2008). As a

consequence, organizations are more and more interested in communicating about their CSR

practices (Eberle et al., 2013). Researches about the effectiveness of CSR communication

towards stakeholders conclude that CSR activities are beneficial for firms because they bring

more positive attitudes (seeking employment, investment), improve brand image and stimulate

supportive behavior (Fombrun et al. 2000; Du et al., 2010). Moreover, CSR activities of a

company can influence customers loyalty and engage them in advocacy behaviors such as

spreading positive word-of-mouth (WOM) or willingness to pay a higher price (Du et al., 2007).

In other words, CSR can not only stimulate consumers’ behavior, but also create more positive

impressions about the company and, thus, influence an organization's attractiveness.

According to Du et al. (2010), companies emphasize on different factors in their CSR

communication, for instance, on reasons why an organization decides to deal with a specific

social issue (their CSR motives) and if there is a match between a cause and business of a firm

(CSR fit). Communication about CSR motives and CSR fit could help to build stakeholders’

positive impression about CSR initiatives and a company in general. As many organizations

today are communicating about their CSR efforts (Eberle et al., 2013), stakeholders are

questioning the reasons of CSR activities that can lead to their skepticism. The understanding of

companies’ motives can influence consumers’ attitude towards a firm and thus, stakeholders’

behavioral intentions such as spreading word-of-mouth (WOM). In addition, perception of CSR

motives could have an impact on identity attractiveness of an organization. For example, values-

driven motives stimulate positive consumers’ attitude towards a company while egoistic motives

stimulate more negative reaction by consumers (Ellen et al., 2006). Thus, we can expect that

positive attitude could lead to higher identity attractiveness.

5

Besides the CSR motives that companies use to communicate, it is also important for a fit

between a goal and a company to exist. Consumers usually expect that organizations will support

only those social issues that have a high (good) fit with company’s corporate business activities

or have a logic association with a brand (Cone, 2007). Moreover, higher CSR fit makes clearer

for consumers why a firm engages in CSR practices and what a company gets from that (Ellen et

al., 2006). The close fit between a cause and company’s business, thus, could evoke consumers’

more positive feelings about an organization in general (Hoeffler & Keller, 2002).

When communicating about CSR motives and CSR fit, credibility of a message is of

utmost importance. If a company's communication is perceived as more credible, consumers will

have more positive attitude towards the information and it is more likely that they will

demonstrate supportive behavior (e.g. spreading WOM and eWOM) (Eberle et al., 2013). What

is more, a truthful and believable message also has a positive impact on attitude towards a

company in general as well as its advertisements (Choi & Rifon, 2002).

The factors of CSR communication such as CSR motives, CSR fit, message credibility

and identity attractiveness could have impact on WOM and eWOM that consumers spread about

an organization. Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) is becoming more powerful today as social

media allows stakeholders to share their opinions about products and companies as well as

maintain two-way communication with organizations (Rim & Song, 2016). Consumers can

spread eWOM via social media about organizations’ CSR activities or a brand in general. If

consumers have positive attitudes toward a brand, this could have impact on their behavioral

intentions, such as spreading positive WOM (eWOM) (Park & Cameron, 2014).

Taking into consideration the mentioned factors that are important in CSR

communication, this study is going to answer the following research question: To what extent do

CSR motives and CSR fit influence consumers’ intention of spreading positive electronic word-

of-mouth (eWOM) about a company? What is role of identity attractiveness and message

credibility in this relationship?

6

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. CSR motives

Gilbert and Malone (1995) supposed that for stakeholders it is more important why

companies are engaging in CSR activities rather than what exactly they are doing. Traditionally,

it was assumed that consumers consider corporate efforts only as self-centered or other-centered

(Ellen et al., 2006). However, later studies found that consumers responses to CSR are more

complex and that there are four types of CRS motives that stakeholders differentiate: egoistic

and strategic (self-centered), and values-driven and stakeholders-driven (other-centered) (Ellen

et al., 2006). Companies with egoistic CSR motives want to exploit the cause for their own profit

rather than help others while strategic-driven motives are connected with the business case

(business goals, e.g., support the positive image, getting more customers and sales) as well as

benefitting the cause (Vlachos et al., 2009). Stakeholders-driven motives are associated with

supporting social issues and CSR activities because of stakeholders’ pressure while values-

driven motives are related to philanthropy and benevolence (Vlachos et al., 2009).

The results of two studies conducted by Ellen et al. (2006) found that consumers react

positively to strategic motives, but negatively to egoistic. Values-driven motives were perceived

more positively while stakeholders-driven motives were seen more negatively (Ellen et al.,

2006). At the same time, consumers demonstrated more positive response to a company with

both self-centered and other-centered motives than those who perceive only one of those motives

(Ellen et al., 2006).

CSR motives of a company are important for CSR communication, thus, the current

study will be focused on them. In this research we decided to take into consideration egoistic and

values-driven motives. These CSR motives seem as the most opposite and logical options

because one of them is self-centered and another one is other-centered as well as Ellen et al.

(2006) research proved that egoistic motives evoke negative reaction while values-driven are

evaluated more positively.

7

2.2. CSR fit

Besides CSR motives, CSR fit is an important factor in CSR communication as it affects

stakeholders’ attribution of CSR (Simmons & Becker-Olsen, 2006). CSR fit is seen as the

perceived congruence between a social issue that a company supports and its business (Du et al.,

2010). Studies provided empirical evidence that the high CSR fit leads to more positive attitude

towards an organization than low fit.

According to Fein (1996), higher fit between a cause and company’s business decreases

the suspicion and make stakeholders perceive more strategic and values-driven motives of CSR

practices while lower fit could increase suspicious and therefore, lead to more egoistic

attribution. Higher CSR fit makes it clearer why an organization gets benefits by engaging in

such activities as well as it could raise the specter of opportunism (Ellen et al., 2006). On the

other hand, the lack of the logical connection between a social issue and company’s business

could lead to low CSR fit. This will probably increase cognitive elaboration and make extrinsic

motives more salient and, thus, reduce the positive reaction of consumers to CSR practices (Du

et al., 2010). This is the reason why companies should highlight CSR fit in their communication,

if this logical connection exists (Du et al., 2010).

The close match between the cause and organization’s business leads to consumers’

attribution of an organization as more expert, and stimulate more positive feelings about the

causes of a company (Hoeffler & Keller, 2002). In addition, an organization with high CSR fit is

seen as motivated to help others, rather than have a desire to egoistically use the causes (Ellen et

al., 2006). In contrast to that, low CSR fit has a negative impact on stakeholders’ beliefs and

attitudes (Simmons & Becker-Olsen, 2006). The results of Ellen et al. (2006) research showed

that the high level of CSR fit encourages consumers to consider a company as more involved,

desired to help and to build the relationships with their customers. Marín, Cuestas & Román

(2016) also supported the idea that the perception of CSR fit is one of the key antecedents of the

persuasive capacity of company communications.

8

Based on previous researches, we assume that high CSR fit leads to stakeholders’ more

positive attitude towards a company’s CSR activities than low CSR fit.

2.3. eWOM, CSR motives and CSR fit

2.3.1. eWOM

Word-of-mouth (WOM) can be defined as informal communication by customers,

directed to other consumers and informing about the ownership, usage, or characteristics of

particular products or services and/or their sellers (Westbrook, 1987). WOM is important for an

organization because information that is spread by consumers is perceived as more reliable than

the information from a company (Bickart & Schindler, 2001).

Word-of-mouth can be positive (pWOM) and negative (nWOM). Positive WOM can be

very influential and persuasive while negative WOM can even stop stakeholders from buying

products or using services with negative reviews (Laczniak et al., 2001). Moreover, several

studies have proved that nWOM could damage company and its reputation because negative

information has more weight for consumers than positive information when they are forming

their impression about a product or service (Herr, Kardes, & Kim, 1991; Ahluwalia, 2002).

Nowadays social media give new opportunities for consumers to share positive and

negative information, discuss topics that they care about as well as create two-way

communication with companies (Rim & Song, 2016). Recent research has supported this idea as

52% of Americans use social media to discuss different issues while 68% of Americans want to

provide direct feedback to an organization (Cone Inc, 2014). The phenomenon of social media is

beneficial for companies and can be useful for CSR communication as well. Today organizations

can use media to communicate directly with the target audience and thus, support two-way

communication with stakeholders (Rim & Song, 2016). In addition, social media communication

helps to cope with public’s skepticism towards CSR initiatives as stakeholders would appreciate

openness and transparency of a company (Du & Vierira, 2012). One of the things that companies

have to deal with in social media in contrast to WOM is electronic word-of mouth (eWOM).

9

eWOM are online statements with different sentiment (positive, negative or neutral) that are

posted by stakeholders about a product, service or an organization in general (Hennig-Thurau

et.al., 2004). Stakeholders use eWOM to share their complaints and opinions about companies

on social media with a large audience (Gruen, Osmonbekov & Czaplewski, 2006).

eWOM is becoming a more important and powerful tool today, however, we still do not

know how does it work in the CSR context. Thus, the main focus of the current research will be

on eWOM.

2.3.2. Interaction of eWOM, CSR motives and CSR fit

Based on the existing literature, which states that egoistic CSR motives lead to negative

reactions from stakeholders while values-driven CSR motives cause more positive response

(Ellen et al., 2006), we suggest that perceived values-driven CSR motives will lead to more

positive eWOM than egoistic CSR motives. Stakeholders will more likely demonstrate

supportive behavior (eWOM) to an organization that is seen more positively. Thus, this will be

the first hypothesis. We assume that the same logic will also work for communicated CSR

motives.

H1: Values-driven CSR motives perceived by consumers lead to more positive eWOM,

than egoistic CSR motives.

Previous research has shown that a logical connection between CSR practices and

company's business leads to more positive feelings about the causes of a company as well as

more positive attitude toward a brand in general (Hoeffler & Keller, 2002; Ellen et al., 2006). On

the other hand, low CSR fit can lead to less positive response from stakeholders (Du et al.,

2010). Therefore, taking into account recent studies about CSR fit, the second assumption is that

higher CSR fit will lead to more positive eWOM.

10

H2: Higher CSR fit leads to more positive eWOM, than low CSR fit.

The interaction effect of CSR motive and CSR fit is also under consideration in the

current study. The assumption is that values-driven CSR motives and high CSR fit together will

lead to the most positive eWOM. Thus, it is the third hypothesis.

H3: Values-driven CSR motives and high CSR fit lead to more positive eWOM, than

values-driven CSR motives and low CSR fit, egoistic CSR motives and high CSR fit or egoistic

CSR motives and low CSR fit.

2.4. Identity attractiveness

Identity attractiveness is considered as an extent to which stakeholders are attracted to an

organization and willing to support relationships with it, giving enduring attributes (Ahearne et

al., 2005). Identity attractiveness is important for companies as according to Dutton et al. (1994),

the extent to which stakeholders are likely to identify with a company depends on the identity

attractiveness of an organization. Marin & Ruiz (2007) concluded that CSR activities of a

company directly influence organization’s identity attractiveness as well as corporate

associations and consumers’ support of CSR actions can have influence on identity attractiveness

of an organization for consumers.

If stakeholders are informed about CSR activities of a company, it has a positive

influence on corporate reputation (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990) and attitude toward the brand

(Brown & Dacin, 1997). Organizations’ attractiveness is higher if companies communicate about

their CSR practices as then stakeholders have a more positive impression about this company.

The identity attractiveness concept allows thinking about relationships between companies and

consumers in a new direction because now not only organizations try to strengthen the link with

stakeholders, but consumers are also interested in the strengthening of their bonds with a

company (Marin & Ruiz, 2007).

11

Different CSR motives could influence identity attractiveness of a company in different

ways. Ellen et al. (2006) study showed that values-driven motives stimulate positive consumers’

attitude while egoistic motives lead to negative reaction. Therefore, we can assume that

organization’s identity attractiveness is lower when consumers perceive CSR motives as

egoistic. In contrast to that, we suppose that identity attractiveness of a company is higher if an

organization has perceived values-driven motives. Consumers are less likely to identify with a

company in the first case and are more likely to identify with an organization in the second.

At the same time, CSR fit could also have an impact on identity attractiveness of a

company. High CSR fit makes stakeholders perceive company’s actions as less egoistic and

more motivated to help others (Ellen et al., 2006) as well as stimulate more positive feelings

(Hoeffler & Keller, 2002). Thus, we propose that organization's’ identity attractiveness will be

higher if a company has high CSR fit than low CSR fit, as that evoke positive attitude toward a

company.

For this research it is important the extent to which consumers feel inclined to engage in

pWOM depends on the extent of embeddedness that also includes closeness and inclusiveness

(Eberle et al., 2013). This could mean that when stakeholders feel that they share the same values

with an organization, this organization seems more attractive to them and stakeholders will

engage in positive eWOM sooner. We can assume that the higher identity attractiveness of an

organization is, the more likely stakeholders will spread positive eWOM.

Thus, we can assume that identity attractiveness plays the mediating role between CSR

motives, CSR fit and consumers’ intentions of spreading more positive eWOM.

H4: The relationship between CSR motives, CSR fit and eWOM will be mediated by

identity attractiveness.

12

2.5. Message credibility

Message credibility can have a significant impact on the perception of CSR

communication. Message credibility could be described as the degree to which stakeholders

perceive a message or communication being truthful and believable (MacKenzie and Lutz,

1989). Choi and Rifon (2002) concluded that the credibility of an advertising message positively

influence the attitude towards advertisements and a company in general. Perceived credibility of

a message and WOM are also linked. Stakeholders see a CSR communication as more credible if

most users’ comments are positive than if the comments are mostly negative (Smith & Vogt,

1995).

Message credibility has positive influence on company’s reputation (Goldsmith et al.,

2000; Eberle et al., 2013). Moreover, a company’s message credibility could have a positive

effect on stakeholders’ intentions of spreading positive WOM (Eberle et al., 2013). When the

communication is seen as credible, customers are more likely to have a positive attitude toward a

brand that leads to the willing to recommend a company to other users (Eberle et al., 2013).

We assume that when CSR motives are perceived as values-driven, CSR fit is high and a

message is perceived as credible, it could enhance the effect on identity attractiveness. On the

other hand, if the message is not seen as trustworthy and stakeholders do not believe the

information, we suggest that it does not matter which CSR motives and CSR fit are perceived by

stakeholders as they are skeptical about information in general. Thus, our assumption is that

message credibility plays a moderating role in the relations between CSR motives, CSR fit and

identity attractiveness. Credibility of a message can make the effect of CSR motives and CSR fit

on identity attractiveness stronger or reduce this effect if a message is perceived as not credible.

H5: The relationship between CSR motives, CSR fit and identity attractiveness will be

moderated by message credibility.

13

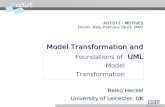

Figure 1. Conceptual framework

Figure 1. Conceptual framework

hfhf

CSR motives

(egoistic vs. values-driven)

CSR fit

(high vs. low)

Identity

Attractiveness eWOM

Message Credibility

H1, H2, H3

H4 H4

H5

14

3. Methods

3.1. Design

To test the hypotheses, a 2 (CSR motives: values-driven vs. egoistic) × 2 (CSR fit: high

vs. low) experimental between-subject design was used. An online experiment with survey was

created in Qualtrics (Appendix A) and distributed via social media (Facebook and Whatsapp).

3.2. Procedure

Firstly, the pre-test was conducted in order to check if manipulations worked as we

expected. The main data was collected in May 2017. Respondents were invited to take part in the

experiment by posting the link to the questionnaire on Facebook and through personal invitations

on Whatsapp and Facebook messenger. The survey was in the English language only.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four experimental conditions. First, the

instructions about the experiment were shown. Then, each participant was asked to read a

scenario with Philips CSR communication on the organization’s official Facebook page. After

that, participant answered questions about CSR motives, CSR fit, credibility of the message that

they have read, indicated their eWOM intentions and the identity attractiveness of the

organization. Also, questions about C-C identification, familiarity with the brand and Facebook

usage were used as control variables in the current study. At the end of the survey, demographic

characteristics (gender, age, nationality, level of education) were included. Participants did not

get any reward for participating in the experiment. It was also indicated that each participant

needed around 5-7 minutes to complete the survey successfully.

3.3. Participants

The final sample consisted of 208 participants where 54% of them are female (112

women) and 46 % are male (96 men). In this research participants were between 18 and 46 (M =

23.38, SD = 3.443) and 43% of them were Dutch while 57% were non-Dutch (36 different

nationalities). Most of the participants were highly educated as 71% of them obtained Bachelor

degree (46%) or Masters degree (25%).

15

3.4. Stimulus material

The experiment had four scenarios. We manipulated two variables: CSR motives and

CSR fit. We chose Philips for the pre-test and the same company was used in the main study. We

decided to use an existing brand in our research because Philips is a world famous company and

especially well-known in the Netherlands. Thus, we supposed that most participants should be

familiar with Philips and have an impression about this organization. It is beneficial for the

research as scenarios could be seen as more realistic.

We manipulated CSR fit to select two communications with high fit between a social

issue and company's business and two communications with low fit (Appendix B). For high CSR

fit we created a post based on the existing Philips project where they claim to becoming carbon

neutral by 2020. For low CSR fit we created a Facebook message about the program where

Philips announces that they will donates more than $1 million to save polar bears in Arctic.

For CSR motives we manipulated a CSR communication post on Facebook to get two

messages with perceived egoistic motives and two messages with perceived values-driven

motives (Appendix B). The messages were created based on items from Ellen et al. (2006) scale.

For example, to communicate values-driven motives we used phrases as “Following the core

values of Philips, we aim to protect the environment for the better future of our planet. As part of

our overarching company vision, we have already made great strides in minimizing our impact

on the environment”. For conditions with egoistic motives we use phrases such as “We decided

to engage in corporate social responsibility project because it is beneficial for our company and

will help to improve brand image. We want to make the public aware that Philips has reduced its

carbon footprint by 42% since 2007”.

In order to check manipulations for CSR motives and CSR fit, a pre-test was conducted.

The sample consisted of 44 participants and 52% of them were female (23 women) while 48%

were male (21 men). Participants were between 18 and 30 (M = 23.02, SD = 2.637). To analyze

the results we used one-way ANOVA. The results showed that manipulation for CSR fit worked

16

as we expected (F(1, 42) = 7.790, p < .01) and there is a significant difference between

conditions with high CSR fit (M= 4.24; SD=1.23) and low CSR fit (M=3.36; SD=0.80).

However, the pre-test demonstrated that manipulation for CSR motives did not work (for values-

driven: F(1, 42) = .880, p = .353; for egoistic: F(1, 42) = .335, p = .566). Therefore, we improved

CSR messages of Philips for the main study. For values-driven posts we also added the phrase

“...Philips Lighting is committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2020 because environment care

is in the culture of our company” and for egoistic posts we used an additional phrase “...Philips

Lighting is committed to becoming carbon neutral by 2020 because that should help to

strengthen our market position and attract new customers”. We reduced the amount of words in

all messages after pre-test to make posts more salient.

3.5. Instrumentation/Variables

Existing scales were used to measure the dependent and independent variable for this

study. Appendix C shows the details of the measures that we chose for the main part of the

research and for the demographic characteristics.

To measure the main dependent variable (eWOM), two adapted scales from Eisingerich,

Chun, Liu, Jia, & Bell (2015) were applied using seven-point Likert scales (1= ‘very unlikely, 7=

‘very likely’). The scales consisted of three items for eWOM about a message (e.g. To what

extent is it likely that you would ‘like’ this message on Facebook?) and four items for eWOM

about an organization (e.g. To what extent is it likely that you would say positive things about

the company on social sites such as Facebook?). Both scales were reliable (eWOM message α =

.78, eWOM organization α = .81).

Perceived CSR motives were measured with the seven-point Likert scale (1= ‘totally

disagree’, 7= ‘totally agree’) adapted from Ellen et al., 2006. The scale included 4 items: two

items for values-driven motives (e.g. I think Philips invests in socially responsible initiatives

because they feel morally obliged to help) and two items for egoistic motives (e.g. I think Philips

17

invests in socially responsible initiatives because they have a hidden agenda). This scale had

acceptable reliability (values-driven motives α = .69, egoistic motives α = .65).

CSR fit was measured with a seven-point Likert scale from Lafferty (2007) (1=’very

incompatible’, 7=’very compatible’; 1= ‘doesn’t make sense at all’, 7= ‘makes a lot of sense’;

1= ‘not believable at all’, 7= ‘very believable’) with an item as ‘Based on the Philips Facebook

post I have just read, I feel the partnership between Philips and the cause they support is…’. The

reliability of this scale was very good (α = .87).

The scale from Newell and Goldsmith (2001) was transformed into a seven-point Likert

scale to investigate the moderating variable - message credibility (1= ‘totally disagree’, 7=

‘totally agree’). The scale consisted of four items (e.g. Based on the Philips post on Facebook I

think Philips makes truthful claims) and was reliable (α = .86).

To measure identity attractiveness, we took the scale from Kim et al. (2001), following

the recommendations of Bhattacharya and Sen (2003) and adapted it to a seven-point Likert

scale (1= ‘totally disagree’, 7= ‘totally agree’). This scale included four items (e.g. Philips is a

very attractive organization). The reliability of the scale was acceptable (α = .72).

Several variables were controlled for in the current study as they might provide

alternative explanations for the hypothesized effects. Our first control variable was familiarity

with a company/brand. As we used an existing brand, participants could have an opinion about

this organization that could influence respondents’ opinion about the message and eWOM

intentions. To measure familiarity we used three items (e.g. To what extent are you familiar with

Philips?) on a seven-point Likert scale (1=‘not familiar at all’, 7= ‘very familiar’; 1=‘never’,

7=‘very frequently’; ‘Yes’ or ‘No’).

The second control variable was identification with a company/brand (C-C

identification). With some organizations stakeholders feel closer and, therefore, they are more

likely to talk more passionately about those companies (Fournier, 1998). In other words, if

stakeholders identify with a company, they will more likely spread WOM or eWOM. Thus, C-C

18

identification could have an impact on eWOM intentions and also on perception of CSR motives.

We applied a seven-point Likert scale from Leach et al. (2008) (1= ‘totally disagree’, 7= ‘totally

agree’). The scale consisted of three items (e.g. I feel a bond with Philips) and the reliability was

very good (α = .89).

We finally controlled for Facebook usage of our participants because that could also

influence eWOM intentions. People who do not use Facebook that often could be less likely to

engage in eWOM in general. A seven-point Likert scale (1= ‘totally disagree’, 7= ‘totally

agree’) based on Ellison et al. (2007) was applied. The scale included three items (e.g. Facebook

is part of my everyday activity) and was reliable (α = .76).

19

4. Results

4.1 Manipulation check

In order to investigate if manipulations of CSR motives and CSR fit worked in Philips

Facebook posts as we expected, we used one-way ANOVA to analyze both manipulations. The

test showed that there was no significant difference between conditions on values-driven and

egoistic CSR motive perceptions. For values-driven items, the analysis revealed the following

F(1, 206) = .417, p= .519 and for egoistic items it showed F(1, 206) = .004, p = .948. Thus, the

manipulation for CSR motives did not work and the effects of CSR motives should be

interpreted with caution.

The test for CSR fit demonstrated that there is significant difference between conditions

with perceived high CSR fit (M = 4.91; SD = 1.25) and low CSR fit (M = 4.21; SD = 1.39) (F(1,

206) = 14.308, p < .001). Therefore, the manipulation for CSR fit worked successfully.

4.2 Hypothesis check

In order to test if communicated values-driven CSR motives lead to more positive

eWOM than egoistic CSR motives (Hypothesis 1), we used one-way ANOVA. The analysis

showed that the difference between the effect of values-driven CSR motives conditions (M=2.81,

SD = 1.36) and egoistic CSR motives conditions (M = 2.74, SD = 1.4) on positive eWOM was

not significant (F(1, 206) = .13, p = .71). Thus, the Hypothesis 1 was not confirmed. In other

words, communicating values-driven motives did not lead to more positive eWOM than

communicating egoistic motives.

To examine the Hypothesis 2, one-way ANOVA test was conducted. The results

illustrated that there was no significant difference between the effect of high CSR fit (M = 2.84,

SD = 1.29) and low CSR fit (M = 2.71, SD = 1.46) on positive eWOM intentions (F(1, 206)=

.44, p = .50). Therefore, the hypothesis that higher CSR fit lead to more positive eWOM, than

low CSR fit was not confirmed.

20

Hypothesis 3 about an interaction effect was also tested with one-way ANOVA. We

wanted to understand if values-driven CSR motives and high CSR fit lead to more positive

eWOM, than 3 other combinations of factors. The test revealed that there was no significant

difference between conditions (F(1.16, 394.2) = .20, p = .89). This means that values-driven

CSR motives and high CSR fit (M = 2.86, SD = 1.32) did not lead to more positive eWOM, than

values-driven CSR motives and low CSR fit (M = 2.76, SD = 1.41), egoistic CSR motives and

high CSR fit (M = 2.82, SD = 1.27) or egoistic CSR motives and low CSR fit (M = 2.66,

SD=1.52). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was not confirmed.

We also examined H1, H2 and H3 dividing eWOM scale into eWOM about the Facebook

message (eWOM message) and eWOM about Philips company in general (eWOM organization).

However, one-way ANOVA tests showed that results were not significant for H1, H2 and H3.

Figure 2. Mediation effect of identity attractiveness for eWOM message

In Hypothesis 4 we assumed that the relationships between CSR motives, CSR fit and

eWOM were mediated by identity attractiveness. In order to test this hypothesis we used

PROCESS model 4 by Andrew F. Hayes that allows checking mediating effect in one model.

Figure 2 shows the mediation model for eWOM about a message. As can be noticed, CSR

motives and CSR fit did not have a significant effect on identity attractiveness while identity

attractiveness was positively related to eWOM message. The direct effect of the conditions (CSR

motives and CSR fit) on eWOM message was not significant (D1 (b = - .27, SE = .26, 95% BCa

CI [- .79, .25]); D2 (b = .06, SE = .27, 95% BCa CI [- .47, .59]); D3 (b = - .11, SE = .26, 95%

BCa CI [- .64, .41]). The indirect effect with the mediation of identity attractiveness was also not

Identity

attractiveness

CSR motives

(egoistic vs. values-driven)

CSR fit

(high vs. low)

eWOM

message

D1 b= .14, p= .44

b= .34, p< .001

D2 b= -.08, p= .66

D2 b= -.18, p= .31

21

significant (D1 (b = .04, SE = .06 95% BCa CI [- .05, .19]); D2 (b = - .02, SE = .07, 95% BCa

CI [- .17, .10]); D3 (b = - .06, SE = .06, 95% BCa CI [- .23, .03]).

Figure 3 demonstrates the mediation model for eWOM about an organization. CSR

motives and CSR fit did not have a significant effect on identity attractiveness while identity

attractiveness was positively related to eWOM message. The direct effect of the conditions (CSR

motives and CSR fit) on eWOM message was also not significant (D1 (b = .04, SE = .27, 95%

BCa CI [- .48, .58]); D2 (b = - .11, SE = .27, 95% BCa CI [- .65, .43]); D3 (b = - .12, SE = .27,

95% BCa CI [- .66, .41]). The indirect effect with the mediation of identity attractiveness was

not significant as well (D1 (b = .05, SE = .06 95% BCa CI [- .05, .19]); D2 (b = - .02, SE = .07,

95% BCa CI [- .17, .12]); D3 (b = - .06, SE = .06, 95% BCa CI [- .24, .04]).

Figure 3. Mediation effect of identity attractiveness for eWOM organization

Thus, there was a positive relation between identity attractiveness and eWOM message as

well as eWOM organization, however, there was no relation between CSR motives, CSR fit and

identity attractiveness. Therefore, identity attractiveness did not mediate the relations between

CSR motives, CSR fit and eWOM. Thus, Hypothesis 4 was not confirmed.

In Hypothesis 5, we assumed a moderating effect of message credibility between the

relationships of CSR motives, CSR fit and identity attractiveness. To test Hypothesis 5 we used

PROCESS model 1 (Hayes, 2013). The analysis revealed that overall model was significant

(F(7,200) =16.37, p < .001, R2= .36). Message credibility (trust) was a significant predictor of

identity attractiveness (b = .41, t(200) = 4.11, p< .001). Analysis also revealed that the

Identity

attractiveness

CSR motives

(egoistic vs. values-driven)

CSR fit

(high vs. low)

eWOM

organization

D1 b= .14, p= .44

b= .36, p< .001

D2 b= -.08, p= .66

D2 b= -.18, p= .31

22

interaction effect of CSR motives, CSR fit and message credibility was not significant (Iteration

1 b= .06, t(200) = .43, p= .66; Iteration 2 b= .09, t(200) = .71, p= .47; Iteration 3 b= .15, t(200) =

1.09, p= .27). Message credibility did not seem to function as a moderator in the relations

between CSR motives, CSR fit and identity attractiveness. Thus, Hypothesis 5 was not

confirmed.

4.3 Additional analysis

To test the strength of relationships between control variables (C-C identification,

Facebook usage, familiarity with a company/brand), the dependent variables (eWOM

organization; eWOM message) and independent variables (CSR fit; CSR motives; message

credibility; identity attractiveness) a correlation Table 1 was created.

Correlations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

1. eWOM (message)

2. eWOM (organization) .68**

3.CSR motives (values-driven) .11 .18**

4.CSR motives (egoistic) -.25**

-.29**

-.32**

5. CSR fit .37**

.33**

.41**

-.29**

6. Message credibility .28**

.35**

.47**

-.45**

.50**

7. C-C identification .36**

.47**

.18**

-.23**

.23**

.43**

8. Identity attractiveness .22**

.24**

.31**

-.16* .33

** .59

** .47

**

9.Facebook usage .15* .18

** .16

* -.04 .10 .17

** .07 .09

10. Familiarity (Do you follow Philips

on Facebook?)

-.10 -.25

** -.09 .08 -.07 -.07 -.18

** -.06 -.20

**

11. Familiarity (How often do you buy

Philips products?)

.06 .07 .01 .03 -.01 .10 .39

** .26

** .12 -.11

12. Familiarity(To what extent are you

familiar with Philips?)

-.04 -.01 .10 -.00 .00 .22

** .27

** .28

** .05 -.15

* .50

**

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Table 1.Correlations

Table 1 shows that there was a positive correlation between C-C identification and

eWOM (message r = .37, p< .01; organization r = .47, p< .01) as well as between C-C

23

identification and message credibility (r = 0.43, p < .01). In other words, the more people

identify with a company, the more positive eWOM will be and the higher message credibility

will be. A positive correlation was found between familiarity with a brand and C-C identification

(r = .39, p < .00), identity attractiveness of a company (r = .26, p < .01). There was a negatively

correlation between egoistic CSR motives and eWOM about organization (r = -.29, p < .01) and

eWOM message (r = -.26, p < .01). Both eWOM were also positively correlated with CSR fit

(message r = .37, p < .01; organization r = .33, p < .01) and with trust (message r = .28, p < .01;

organization r = .35, p < .01). A positive correlation was found between CSR fit and message

credibility (r = .51, p < .01).

A multiple regression was conducted to test the influence of independent variables and

control variables on eWOM about the message as this can help us to find some new interesting

results. After we have added variables to the model, the effect of the strongest predictors was

still significant (Table 2). The general model was significant (F(7, 200) = 9.85, p < .001) with

R2

of .257. The analysis showed that С-С identification (β= .27, t(207) = 3.98, p < .01) and CSR

fit (β = .31, t(207) = 4.29, p < .01) significantly predicted eWOM message. Thus, we can

conclude that the more consumers identify with an organization, the more positive eWOM they

will spread and the higher perceived CSR fit is, the more positive eWOM (message) will be,

after controlling the effect of all other variables. Egoistic CSR motives also significantly

predicted eWOM message (β= - .13, t(207) = - 2.05, p < .05). In other words, the more

consumers perceive motives as egoistic, the less likely that they will spread positive eWOM

about a message.

One more regression model was created in order to check the effect of the same

independent variables on eWOM about a brand. A significant regression equation was found

(F(7, 200)= 13.03, p < .001) with R2 of .313). The results demonstrated that C-C identification

and perceived CSR fit are significant predictors of eWOM organization (C-C identification β =

.38, t(207) = 5.79, p < .01); fit: (β = .21, t(207) = 2.91, p < .01) after controlling the influence of

24

all other variables. Egoistic CSR motives significantly predicted eWOM message as well (β= -

.13, t(207) = - 2.01, p < .05). Thus, we can expect that the more consumers perceive motives as

egoistic, the less likely that they will spread positive eWOM about an organization.

Model 1 eWOM

message

Model 1

eWOM

organization

Determinants t t

C-C identification .27 3.98** .38 5.79**

Facebook usage .10 1.91 .11 2.14*

Perceived fit .31 4.29** .21 2.91**

Perceived values-driven motives -.13 -1.75 -.04 -.58

Perceived egoistic motives -.13 -2.05* -.13 -2.01*

Identity attractiveness -.00 - .03 -.09 -.81

Message credibility -.02 -.20 .06 .54

R2 .25 .31

F 9.85*** 13.03***

Df 207 207

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Table 2. Hierarchical Regression to predict eWOM

Finally, based on the regression analysis and correlations between C-C identification,

identity attractiveness and eWOM, we checked the mediation effect of C-C identification (Figure

3). The PROCESS model 4 (Hayes, 2013) was used. We assumed that the relationship between

identity attractiveness and eWOM about the organization was mediated by C-C identification.

Analysis revealed that identity attractiveness had a significant effect on C-C identification

(b= .75, SE = .00, 95% BCa CI [ .56, .58] and C-C identification had a significant effect on

eWOM (b = .44, SE = .00, 95% BCa CI [ .30, .57]. The direct effect of identity attractiveness on

eWOM was not significant (b = .04, SE = .69, 95% BCa CI [- .17, .25]. Therefore, C-C

25

identification fully mediated the relations between identity attractiveness and eWOM about the

organization.

Figure 4. Mediation effect of C-C identification

Identity attractiveness

C-C identification

eWOM

organization

b = .04, p= .69

b = .75, p < .001 b = .44, p < .001

26

5. Discussion & Conclusion

5.1. Findings

The current study was conducted to investigate to what extent CSR motives and CSR fit

influence consumers’ intention of spreading positive electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) about a

company and the role of identity attractiveness and message credibility in this relationship.

Based on the existing literature, several assumptions were examined in order to answer the main

research question.

In Hypothesis 1, we assumed that values-driven CSR motives perceived by consumers

lead to more positive eWOM, than egoistic CSR motives. The idea was based on Ellen et al.,

(2006) who found that egoistic CSR motives will lead to more negative reactions from

stakeholders (eWOM in our case) while values-driven CSR motives will cause more positive

response (eWOM) (Ellen et al., 2006). However, Hypothesis 1 was not confirmed, so

communicating values-driven motives did not lead to more positive eWOM than communicating

egoistic motives. It means that for participants there was no difference between communicating

values-driven or egoistic CSR motives when it comes to eWOM. An explanation why the

hypothesis was not confirmed could be that according to results of Ellen et al. (2006),

stakeholders show the most positive reaction to companies with both other-centered and self-

centered CSR motives. In other words, if consumers attribute both motives to company’s CSR

activities, they will have more positive intentions (e.g. eWOM) than those who attribute either

only other-centered or self-centered motives. The current study was focused on one sided CSR

messages. In one case, we used one communication with only other-centered motives (values-

driven) and in another, the communicated motives were self-centered (egoistic). It could be that

for consumers the difference between values-driven and egoistic motives is not that critical in the

context of eWOM intentions while they could react much more positively to two-sided messages

(with acknowledging both other-centered and self-centered motives). Although, consumers are

usually skeptical and could perceive business cynically, they could expect that a company can

27

follow their own goals as well as society needs (Ellen et al., 2006). It could be that stakeholders

would perceive a company as more honest and thus, will respond more positively, if this

company communicates about both CSR motives. Forehand and Grier’s (2003) found that the

negative impact of stakeholders’ skepticism could be reduced by acknowledging organization

benefits and it will also help to increase the credibility of company’s CSR message. This means

that stakeholders could be less skeptical about CSR activities and therefore, could respond more

positively if a company communicates about its social motives (other-centered) as well as admits

its own benefits (self-centered). One more explanation of our results could be that manipulation

for CSR motives did not work. In other words, participants did not experience the difference

between two conditions: Facebook posts with communicated values-driven CSR motives and

egoistic CSR motives. We used world famous brand in our experiment and this could have

influence on the final result. Most respondents probably already had an impression about this

company. Thus, just one post could not have a strong influence on people’s positive or negative

opinion about Philips or their CSR program.

Recent research has proved that stakeholders expect high fit between the cause and

organization’s business (Cone, 2007). In addition, high fit leads to more positive feelings about

the causes of a company and more positive attitude toward it (Hoeffler & Keller, 2002; Ellen et

al., 2006). Thus, in Hypothesis 2 we assumed that higher CSR fit leads to more positive eWOM,

than low CSR fit. This prediction was not supported by our study and Hypothesis 2 was not

confirmed. For participants there was no difference if CSR fit between the social issue and

organization business was high or low when we talk about eWOM intentions. We assume that

the major reason could be that the impact of CSR fit is not that obvious. On the one hand, most

literature argued that high CSR fit leads to more positive response from stakeholders. On the

other hand, some researchers concluded the opposite. For example, there is an assumption that

was proved by Bloom et al. (2006) that sometimes the low CSR fit communication may actually

lead to more positive reaction of consumers. The explanation for that could be that low-fit cause

28

can differentiate an organization as more sincere in its motive and, therefore, stimulate the rise of

the effectiveness of its CSR communication (Bloom et al., 2006). Although, high fit makes it

more obvious why a firm engages in CSR activities and gets benefits from that, it could also lead

to the feeling of opportunism (Ellen et al., 2006). In other words, consumers could have doubts

about the honesty of an organization with high fit as well as about its goals. In addition, high fit

could evoke stakeholders’ skepticism and could even lead to more negative response to CSR

messages (Drumwright, 1996). It could mean that for stakeholders and their eWOM intentions it

does not matter if the CSR fit is high or low as in both cases they could have doubts about the

purposes of a company. In general, the effect of CSR fit on eWOM intentions of stakeholders

could be more complex than it was expected. We also assume that for participants it could be

difficult to base their opinion about a company or their CSR program only on one message. One

Facebook post probably can not form or influence the perception of a brand. There is also a lot of

space for consumers’ skepticism about CSR activities.

In Hypothesis 3, we assumed that values-driven CSR motives and high CSR fit lead to

more positive eWOM, than values-driven CSR motives and low CSR fit, egoistic CSR motives

and high CSR fit or egoistic CSR motives and low CSR fit. Hypothesis 3 was not confirmed. The

explanation of this could be that in general the impact of CSR motives and CSR fit on eWOM is

not clear. We assume that the effect of CSR motives would be not that strong if one-sided

messages (with only communicated other-centered or self-centered motives) are used as

stakeholders demonstrate the most positive response to firms with both other-centered and self-

centered CSR motives (Ellen et al., 2006). In addition, the effect of high and low CSR fit could

be controversial as some studies discovered the negative effect of high CSR fit (Bloom et al.,

2006). Therefore, it could be that even if CSR fit is high and communicated motives are values-

driven, stakeholders could be still skeptical and the effect is still not strong enough to lead to

positive eWOM.

29

CSR activities have a direct influence on organization’s identity attractiveness (Marin &

Ruiz, 2007). In addition, consumers will more likely spread pWOM if they feel closeness with

an organization and inclusiveness (Eberle et al., 2013). Thus, a company will be more attractive,

if stakeholders perceive that they share the same values with this company and stakeholders will

engage in positive eWOM sooner. Therefore, we supposed that the relationship between CSR

motives, CSR fit and eWOM would be mediated by identity attractiveness (Hypothesis 4). Our

study showed that communicated CSR motives and CSR fit did not affect identity attractiveness

of a company while identity attractiveness had impact on eWOM. In other words, identity

attractiveness did not mediate the relationship between CSR motives, CSR fit and eWOM. Thus,

Hypothesis 4 was not confirmed. As the results showed, CSR motives and CSR fit did not have

impact on identity attractiveness of the company. The influence of CSR fit could be controversial

as some studies proved the negative effect of high fit (Drumwright, 1996; Bloom et al., 2006)

while the effect of CSR motives is not clear as one-sided messages could be not enough

influential (Ellen et al., 2006). Thus, we assume that for stakeholders it is not that critical which

CSR motives an organization communicates and if the CSR fit is high or low. It could be that the

most important for consumers is the fact that company engages in CSR in general when it comes

to eWOM. In previous studies it was found that there is a relationship between CSR practices

and positive behavioral responses of stakeholders (Mohr and Webb, 2005; Bhattacharya and Sen,

2001). In addition, Marin & Ruiz (2007) proved that CSR projects directly influence identity

attractiveness of a firm. In other words, consumers could have a more positive attitude and show

supportive behavior (eWOM) only because a company has a CSR program as this is more

significant for them than communicated CSR fit or CSR motives. One more reason that we used

to explain previous hypotheses as well could be that one post is not that powerful to affect

customers view. In other words, only one CSR message of Philips that our participants read

probably could not influence their opinion about CSR program and impact the identity

attractiveness of the company.

30

Hypothesis 5 stated a moderation effect of message credibility as we assumed that it

moderates the relationship between CSR motives, CSR fit and identity attractiveness. According

to Eberle et al. (2013), the more company's message is perceived as credible, the more likely it is

that stakeholders will have positive attitude towards the information there and it is more likely

that they will demonstrate supportive behavior such as eWOM. Our hypothesis was not

confirmed as message credibility did not moderate the relationship between CSR motives, CSR

fit and identity attractiveness. Nevertheless, according to our results, message credibility directly

affected identity attractiveness of a company. It means that identity attractiveness is higher if

organization message is perceived as truthful. Therefore, it could be that message credibility has

influence only on attitude toward a company (Choi and Rifon, 2002) and organization reputation

(Goldsmith et al., 2000; Eberle et al., 2013) as it was proved in previous studies. In other words,

message credibility could only have influence on identity attractiveness. At the same time, could

be that there is no impact of message credibility on the relationship between CSR motives, CSR

fit and identity attractiveness in general as stakeholders could be skeptical about CSR motives

and CSR fit. It means that if, for example, motives are values-driven and CSR fit is high, the

credibility of a message still does not make the effect of CSR motives and CSR fit stronger or

weaker. One more reason could be that there was no effect of CSR fit and CSR motives on

identity attractiveness. Thus, even if the message is perceived as credible, the effect of conditions

on identity attractiveness is still not noticeable.

Although, our hypotheses were not confirmed, some additional results were revealed.

Firstly, identity attractiveness of a company positively affected eWOM. In addition, C-C

identification fully mediated the relationship between identity attractiveness of a brand and

intentions of spreading eWOM about an organization (not about the message). In other words, if

a company was attractive for consumers, they would more likely identify with this company and

that could lead to more positive eWOM about this organization. Our results supported the

previous findings that identity attractiveness influence the extent to which stakeholders are likely

31

to identify with an organization (Dutton et al., 1994) and that stakeholders who identify

themselves with a company are more likely to spread positive WOM (eWOM) about it (Eberle et

al, 2013).

Secondly, message credibility had a direct influence on identity attractiveness of the

company. This means that the more the post was perceived as credible, the more the company

seemed attractive to consumers. This finding confirmed the results of previous studies which

stated that message credibility positively influence firm’s reputation (Goldsmith et al., 2000;

Eberle et al., 2013) as well as the attitude towards a message and an organization (Choi and

Rifon, 2002).

Thirdly, while Hypothesis 2 was not confirmed, the effect of perceived CSR fit on

eWOM about a company and on eWOM about a message was found after controlling for other

factors. It means that if consumers saw the fit between the issue and business, it is more likely

that they would spread positive eWOM about a brand or/and a company’s message. Our study

proved the results from other researches that high CSR fit reduces the suspicion (Fein, 1996),

makes company’s interests more clear (Ellen et al., 2006) and support more positive feelings

about the purpose and the brand in general (Hoeffler & Keller, 2002).

Finally, although communicated CSR motives did not affect eWOM intentions, the effect

of perceived egoistic CSR motives on eWOM about a message and an organization was found

after controlling for other variables. This means that if participants perceived motives as egoistic,

they will spread less positive eWOM. The current research supported the findings of Ellen et al.

(2006) that consumers react negatively to egoistic CSR motives.

In the current study we assumed that CSR message and communicated information there

(CSR fit, CSR motives) have influence on eWOM intentions of stakeholders. It was supposed

that different attitudes toward CSR message could evoke different behavior in social media. The

results of this research did not support this idea. Thus, what if CSR message does not have

influence on eWOM intentions in general?

32

Most of the times, consumers spread WOM or eWOM to express their extreme

satisfaction or dissatisfaction with a product (Maxham and Netemeyer, 2002) or their opinion

about a new product (Bone, 1995). It could be that a message about organization CSR project

does not enough motivate stakeholders to spread eWOM as the information in that message does

not evoke that strong emotions. For example, there could be no difference if communicated CSR

motives are values-driven or egoistic as they are not influential enough to stimulate stakeholder

to spread eWOM in general. Probably, consumers would be more motivated to engage in eWOM

about CSR activities of a company on social media if a CSR post is more outstanding, attracts

more attention or informs stakeholders about something that impresses them.

In addition, there is one critical difference between WOM and eWOM that can have

effect on consumers’ intentions. WOM is usually spread in private conversation where the direct

observation is difficult and it is ephemeral (Jalilvand, Esfahani and Samiei, 2010). Thus, people

could feel more free to share their opinions and thoughts. In contrast to WOM, eWOM is

directed to a big audience, spreads more widely and rapidly as well as is available anytime

(Jeong and Jang, 2011). Therefore, it could be that stakeholders see more social risks and are

more careful with engaging in eWOM in general as everyone can see what they post or what

they “like” on social media. In our case, stakeholders could have less intentions to spread eWOM

about a company or CSR message as it could be observed by a lot of people and stakeholders

could feel less comfortable, more responsibility for their words.

5.2. Practical implications

Results of the study have practical implications for organizations. For customers there

seen to be no difference between communicating values-driven or egoistic CSR motives.

However, perceived egoistic CSR motives could have negative influence on eWOM intentions.

Thus, it could be more effective to create two sided messages (communicate both other-centered

and self-centered motives). It could make stakeholders feel that a company is more honest and

they will have more positive behavioral intentions such as spreading positive eWOM.

33

As perceived CSR fit has influence on eWOM intentions, it is important for companies to

communicate about CSR fit between the cause that company supports and its business. If

consumers understand why an organization do CSR (the fit seems logical and clear) and perceive

CSR fit as high, it is more likely that they will spread positive information about a brand and

about CSR post on social media.

Message credibility does not have the influence on the relationship between CSR

motives, CSR fit and identity attractiveness of a company. However, message credibility directly

influences identity attractiveness of an organization. Thus, it is critical for companies to pay

attention to make trustful and credible messages about their CSR activities as then the identity

attractiveness of a brand will be higher. For example, it could be achieved by creating two-sided

messages where a company also acknowledges its benefits as according to Forehand and Grier’s

(2003) admitting benefits could help to increase the credibility of company’s CSR message. If

customers believe the information that they receive, company seems more attractive to them. In

addition, if a brand is attractive, consumers will more likely identify with this organization as

well as that could lead to positive eWOM intentions. It means that if stakeholders feel the

belonging to the company and its values, they will more likely to share company’s CSR

information on social media (e.g. Facebook), to post positive comments or to “like” them.

5.3. Limitations and future research

Some limitations of the current research should be mentioned as well. Firstly, although,

our messages were created basing on Ellen et al. (2006) items and pre-tested, in the main study

the manipulations for CSR motives did not seem to work properly. That could be a reason why

our hypotheses were not confirmed. Secondly, for the experiment we chose an existing brand

(Philips) and this fact might have influenced the results. On the one hand, it is a well-known

brand and people are familiar with it. On the other hand, people’s opinions about Philips could

be biased and they could have already formed their positive or negative impression about the

34

company. We assume that as participants probably already had their opinion about Philips, just

one Facebook post that we used in the experiment could not have strong influence on them.

For future researches, it could be interesting to conduct a replication study where

manipulation for CSR motives would work successfully. Also, it could be possible to develop

the same study but with a non-existing brand (we used an existing company) to test the

difference between the results. We assume that this factor could have influence on participants’

attitudes and answers.

This study also demonstrated that there could be difference between communicated and

perceived CSR fit and CSR motives. In our research perceived egoistic motives had negative

influence on eWOM while communicated egoistic motives did not have effect on eWOM. Also,

perceived CSR fit had impact on eWOM intentions. Although, it was not the main focus of the

current research, in the future it could be interesting to investigate the difference between the

effects of communicated as well as perceived fit and motives on stakeholders’ intentions. We

suppose that perceived motives and fit would have stronger influence than communicated.

In our research we used only one-sided messages, namely one communication with other-

centered motives (values-driven) and one communication with self-centered motives (egoistic).

It could be useful to test messages with both other-centered and self-centered motives as well as

with different combinations of them. It could be that two-sided communication will have more

impact and will lead to more positive eWOM than one-sided. In addition, we made an

assumption that one message could not be enough to form or influence stakeholders’ opinion. In

the future studies, it is possible to show participants several posts instead of one as that can have

stronger effect on their perception of a CSR program.

Also, it would be possible to emphasize on the duration of a CSR program in further

studies. Short term programs could lead to stakeholders feeling that a company participates in

CSR only to satisfy others expectations (Ellen et al., 2006) and that could evoke skepticism as

well as cause negative impression. Thus, it could be better to communicate about a long term

35

CSR project in experiment posts to reduce participants’ skepticism, and the general impression

about a company would be more positive. Then, the effect of CSR communication could be

stronger and participants will have more eWOM intentions.

5.4. Conclusion

To sum up, this study showed that for stakeholders there was no difference between

values-driven and egoistic CSR motives as well as high and low CSR fit on eWOM intentions.

Identity attractiveness was not a mediator between CSR motives, CSR fit and eWOM. Message

credibility did not moderate the relationship between CSR motives, CSR fit and eWOM.

36

6. References

Ahearne, M., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Gruen, T. W. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of customer-

company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. Journal of Applied

Psychology,90(3), 574.

Ahluwalia, R. (2002). How prevalent is the negativity effect in consumer environments?.Journal of

Consumer Research, 29(2),270–279.

Bhattacharya, C. B., &Sen, S. (2003). Consumer–company identification: A framework for

understanding consumers relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 76–88.

Bickart, B., & Schindler, R. M. (2001). Internet forums as influential sources of consumer information.

Journal of Interactive Marketing, 15(3), 31–40.

Bloom, P.N., Hoeffler, S., Keller, K.L., & Meza, C. (2006). How social-cause marketing affects

consumer perceptions. MIT Sloan Management Review, 47, pp. 49–55.

Bone, P. F. (1995). Word-of-mouth effects on short-term and long-term product judgments. Journal of

Business Research,32, pp. 213–223.

Brown, T. J., & P. A. Dacin (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer

product responses, Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84.

Choi, S., &Rifon, N. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of web advertising credibility: A study of

consumer response to banner ads. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 3(1), 12–24.

Cone (2007). Cause evolution survey. Available from: http://www.coneinc.com/content1091, (accessed

19 May 2008).

Cone Inc. (2014). Cone communications digital activism study. Retrieved from

http://www.conecomm.com/stuff/contentmgr/files/0/d57319dec5d8afe4010bf0560a7e4d46/files/

2014_cone_communications_digital_activism_study_final.pdf.

Dahlsrud, A. (2008). How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions.

Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15(1), 1–13.

37

Drumwright, M. E. (1996). Socially responsible organizational buying: Environmental bluying as a

noneconomic buying criterion, Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 1–19.

Du, S., &Vierira, E. T. (2012). Striving for legitimacy through corporate social responsibility: Insights

from oil companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 110(4), 413–427.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S., (2007). Reaping relational rewards from corporate social

responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. International Journal of Research in

Marketing, 24(3), 224–241.

Du, S., Bhattacharya, C.B., & Sen, S. (2010). Maximizing business returns to corporate social

responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. International Journal of Management

Reviews, 12(1), 8–19.

Dutton, J. E., J. M. Dukerich, & J. M. Harquail (1994). Organizational images and member

identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 239–263. doi:10.2307/2393235.

Eberle, D., Berens, G., & Li, T. (2013). The impact of interactive corporate social responsibility

Communication on Corporate Reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 118(4), 731-746.

Eisingerich, A. B., Chun, H., Liu, Y., Jia, H., & Bell, S. J. (2015). Why recommend a brand face-to-face

but not on Facebook? How word-of-mouth on online social sites differs from traditional word-

of-mouth. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(1), 120-128. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2014.05.004

Ellen, P.S., Webb, D.J., & Mohr, L.A. (2006). Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions

for corporate socially responsible programs. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,

34(2), 147–157.

Ellison, N.B., Steinfield, C.,& Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Social capital and

college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun, 12, 1143–

1168.

Fein, S. (1996). Effects of suspicion on attributional thinking and the correspondence bias. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 70(6), 1164–1184.

38

Fombrun, C., &Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy.

Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258.

Fombrun, C., Gardberg, N. A., & Barnett, M.L. (2000). Opportunity platforms and safety nets: corporate

citizenship and reputational risk. Business and Society Review, 105, pp. 85–106.

Forehand, M. R., &Grier, S. (2003). When is honesty the best policy? The effect of stated company

intent on consumer skepticism. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 13(3), 349–356.

Fournier, S. (1998). Consumer and their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research.

Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 343–373.

Gilbert, D. T., & Malone, P. S. (1995). The correspondence bias. Psychological Bulletin, 117(1), 21–38.

Goldsmith, R., Lafferty, B., & Newell, S. (2000). The impact of corporate credibility and celebrity

credibility on consumer reaction to advertisements and brands. Journal of Advertising, 29(3),

43–54.

Gruen, T. W., Osmonbekov, T., &Czaplewski, A. J. (2006). eWOM: The impact of customer-to-

customer online know-how exchange on customer value and loyalty. Journal of Business

Research, 59(4), 449–456. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.10.004

Hayes, A. F. (2013). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New

York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., Walsh, G., &Gremler, D. D. (2004). Electronic word-of-mouth via

consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the Internet?

Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18, 38–52.

Herr, P. M., Kardes, F. R., & Kim, J. (1991). Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute

information on persuasion: An accessibility-diagnosticity perspective. Journal of Consumer

Research, 17(4), 454.

Hoeffler, S., & Keller, K. L. (2002). Building brand equity through corporate societal marketing.

Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 21(1), 78–89.

39

Jalilvand, M. R., Esfahani, S. S., &Samiei, N. (2010). Electronic word of mouth: Challenges and

opportunities. Procedia Computer Science, 3, 42–46. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2010.12.008.

Jeong, E., & Jang, S. (2011). Restaurant experiences triggering positive electronic word-of-mouth

(eWOM) motivations. Int. J. Hosp. Manag, 30, 356–366.

Kim, C. K., D. Han, & S. B. Park (2001). The effect of brand personality and brand identification on

brand loyalty: Applying the theory of social identification. Japanese Psychological Research,

43(4), 195–206.

Laczniak, R. N., Decarlo, T. E., &Ramaswami, S. N. (2001). Consumers’ response to negative word-of-

mouth communication: An attribution theory perspective. Journal of Consumer Psychology,

11(1), 57–73.

Lafferty, A. (2007). The relevance of fit in a cause-brand alliance when consumers evaluate corporate

credibility. Journal of Business Research, 60, 447–453.

Leach, C. W., van Zomeren, M., Zebel, S., Vliek, M. L. W., Pennekamp, S. F., Doosje, B., Ouwerkerk,

J. W., & Spears, R. (2008). Group-level self-definition and self-investment: A hierarchical

(multicomponent) model of in-group identification. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 95(1), 144-165. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.144

MacKenzie, S., & Lutz, R. (1989). An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude

toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 48–65.

Marin, L., & Ruiz, S. (2007). "I need you too!" Corporate identity attractiveness for consumers and the

role of social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 71(3), 245-260.

Marín, L., Cuestas, P.J., & Román, S. (2016). Determinants of consumer attributions of corporate social

responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 138(2), 247–260.

Maxham, J. G., &Netemeyer, R. G. (2002). A longitudinal study of complaining customers' evaluations

of multiple service failures and recovery efforts. Journal of Marketing, 66(4), pp. 57–71.

Mohr, L. A., &Webb, D. J. (2005). The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer

responses. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(1), 121–147.

40

Newell, S., & Goldsmith, R. (2001). The development of a scale to measure perceived corporate