the relationship between helping alliance and outcome in outpatient

Transcript of the relationship between helping alliance and outcome in outpatient

Alcohol & Alcoholism Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 241-249, 1997

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HELPING ALLIANCE AND OUTCOMEIN OUTPATIENT TREATMENT OF ALCOHOLICS: A COMPARATIVE

STUDY OF PSYCHIATRIC TREATMENT AND MULTIMODALBEHAVIOURAL THERAPY

AGNETA OJEHAGEN*, MATS BERGLUND1 and LARS HANSSON

Department of Neuroscience, Division of Psychiatry, University Hospital of Lund, S-22185 Lund, Sweden and 'Department ofAlcohol Diseases, MalmS General Hospital, Malmo, Sweden

{Received 24 June 1996; in revised form 7 November 1996; accepted 11 November 1996)

Abstract — During the last decades, a positive relation between a good alliance and a successfultherapy outcome has been demonstrated across a variety of different therapeutic modalities. Therelationship between alliance and drinking outcome in long-term treatment of alcoholics (12 months ormore) has not, as far as we know, been presented. In the present study, alcoholics were randomized totwo outpatient treatment programmes; multimodal behavioural therapy (MBT) and psychiatrictreatment based on a psychodynamic approach (PT). As part of the study, analyses were performedconcerning differences in alliance between the two treatment models (MBT, n = 17; PT, n = 18), andconcerning the relationship between alliance and treatment outcome. A Swedish version of the HelpingAlliance Questionnaire was used to measure alliance. All therapy sessions were tape-recorded. Anindependent researcher rated the patient's and therapist's contribution to the alliance at the thirdsession (early alliance). Early patient and therapist alliances were not related to sociodemographic dataor initial measures of alcohol severity, psychiatric symptoms, or personality structure in either therapy.Early therapist alliance was better in MBT in comparison with PT. For MBT patients, a significantpositive correlation was found between early patient alliance and mood dimensions at 6 months. Therewere no significant positive correlations between early alliance and drinking outcome during thecourse of treatment and in the third year after start of treatment. Mood and drinking outcome alsoshowed low correlations. In conclusion, an initial positive alliance seems insufficient to reduce alcoholmisuse. The relationship between early alliance and improvement in alcohol misuse needs to be furtherinvestigated.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades the role of alliance inpsychotherapy has received special attention.The construct of therapeutic alliance has beendescribed in several ways, but most constructsinclude some of the following components: (1) thepatient's affective relationship to the therapist; (2)the patient's capacity to work purposefully intherapy; (3) the therapist's empathic understand-ing and involvement; (4) patient-therapist agree-

•Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

ment about the goals and tasks of therapy (Gaston,1990). The positive relation between a goodalliance and a successful therapy outcome isreasonably well documented across a variety ofdifferent therapies (Horvath and Luborsky, 1993),although the average overall effect size(ES = 0.26) is not very large (Horvath andSymonds, 1991). The helping alliance in treatmentof substance use disorders has been addressed byLuborsky and coworkers in a methadone main-tenance sample (Luborsky et al., 1985). Theyfound that early alliance (third session) waspositively related to outcome measures of ASI(Addiction Severity Index), i.e. drug use, employ-

241

1997 Medical Council on Alcoholism

Dow

nloaded from https://academ

ic.oup.com/alcalc/article-abstract/32/3/241/136456 by guest on 05 April 2019

242 A. OJEHAGEN et al.

ment status and psychological functioning (meanr s = 0.65) after 7 months. The duration of theintervention in that study was 12-16 weeks.However, the relationship between alliance anddrinking outcome in alcohol use disorders in long-term treatment, i.e. 12 months or more, has notbeen presented as far as we know.

In comparison with general psychotherapy, theobjectives in alcoholism treatment are twofold: toreduce the alcohol abuse and to achieve animprovement in other areas, i.e. mental healthand social adjustment.

Although the concept of therapeutic alliancewas originally grounded in psychoanalytic theory,there is little reason to believe that the quality ofalliance, as it is currently defined, is moreimportant in analytically oriented interventionsthan in other modalities of therapy. On thecontrary, a better alliance has recently beenfound in cognitive and behavioural therapy, incomparison with psychodynamic-interpersonaltherapy (Raue et al., 1993).

In the present study, alcoholics were random-ized to two outpatient treatment programmes;multimodal behavioural therapy (MBT) (Lazarus,1981), and psychiatric treatment based on apsychodynamic approach (PT) (Luborsky, 1984).Both treatment programmes have been describedin a previous paper (Ojehagen et al., 1992). Themain results of the randomized part of the studyand the influence of psychopathology on clinicaloutcome have been reported in previous articles.There were no significant outcome differencesbetween the two treatment models during thecourse of treatment or in the third year after startof treatment (Ojehagen et al., 1992). A favourabledrinking outcome was predicted by a better initialpsychiatric status and fewer psychiatric symptomsat intake (Ojehagen et al, 1991).

In this part of the study three issues in patientswho completed therapy will be addressed: (1) isthere a difference in early alliance between MBTand PT?; (2) is the level of early alliance related tomood outcome during treatment?; (3) is the levelof early alliance related to drinking outcomeduring treatment and in the third year after startof treatment?

Two other issues are also addressed: (1) areinitial patient characteristics related to the level ofearly alliance?; (2) are mood dimensions anddrinking outcome related during the first year?

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

The series consisted of all subjects whoattended an outpatient alcoholism treatmentstudy at the Department of Psychiatry, UniversityHospital, Lund from July 1983 to June 1985. TheMedical Ethics Committee of the University ofLund approved of the study, and the subjects hadgiven their consent to participate in writing.Inclusion in the programme was preceded bytwo sessions together with a senior psychiatristwith at least one week between the sessions. Thepatient could be either an in- or outpatient at thefirst session, but had to be an outpatient at thesecond session, when he/she made the decision toenter the programme. The patient had to be soberat both sessions. No other exclusion criteria wereused. Seventy-two patients, 60 men and 12women, accepted participation in the study aftertwo information sessions with a senior psychia-trist, whereas 57 did not join the programme(Ojehagen et al., 1992). The acceptors had a meanage of 37 ± 9 years, 74% were married orcohabiting, 68% were regularly employed and57% had 10 years of education or more. Half ofthe sample had previously been treated foralcoholism (Ojehagen et al., 1992). The subgroupof patients included in this investigation of earlyalliance (n = 35) did not differ significantly fromthe others in measurements used in this study.

A factorial design was used in which subjectswere randomized to psychiatric treatment based ona psychodynamic approach (n = 36) or multi-modal behaviour therapy (n = 36), and to 1 or 2years in treatment. The treatment programmeswere not based on manuals.

Twenty-five patients (35%) did not completetherapy; three of them had died, four moved toanother area and 18 (seven in PT) left therapyprematurely. Forty-seven patients completed treat-ment, and 43 of them were followed up 36 monthsafter start of treatment (Ojehagen et al., 1992). Ofthese 43, only patients with complete sets of moodassessments (before treatment and three, six and12 months after start of treatment) were includedin the analysis (MBT, n = 17; PT, n = 18).Nineteen of these patients had 1 year of treatment,and 16 patients had 2 years of treatment. Threepatients in MBT and one in PT were women.

The number (mean ± SD) of treatment sessions

Dow

nloaded from https://academ

ic.oup.com/alcalc/article-abstract/32/3/241/136456 by guest on 05 April 2019

HELPING ALLIANCE AND OUTCOME IN ALCOHOLISM TREATMENT 243

(MBT: 24.7 ± 1.7; PT: 24.6 ± 1.7) did not differbetween the therapies, and was not related todrinking outcome. Nor did number of treatmentsessions differ between 1 and 2 years of treatment(Qjehagen et al., 1992).

Therapists

In MBT, there was one therapist, while therewere three therapists in PT. A change of therapistoccurred for one-third of the patients during thefirst half of the study period, because ofpregnancy. The therapists did not differ signifi-cantly concerning education and training. Theywere all trained in the specific type of treatmentgiven (Qjehagen et al., 1992).

Methods

Initial ratings were performed by the seniorpsychiatrist at the second information session. Theself-rating instruments were all presented byindependent research assistants before the random-ization procedure. The intake- and outcomemeasures except for the measure of helpingalliance and mood dimensions below have beendescribed in detail in a previous paper (Qjehagen etal., 1992).

Helping alliance. A Swedish version of theHelping Alliance Questionnaire (Morgan et al.,1982) translated by B.-A Armelius and M. Phelanwas used to measure alliance. The concept 'help-ing alliance' is operationalized into 20 items. Itcontains two parts, one measuring the therapist'scontribution to the alliance, and the other thepatient's contribution. Each item has a negativeand a positive pole, 1-10, where 10 is the mostpositive value. All therapy sessions were tape-recorded. From these tape-recordings, an indepen-dent rater with experience as a therapist rated thepatient's and therapist's contribution to thealliance at the third session (early alliance) andat the third to last session of the therapy (latealliance) for patients who completed treatment(n = 43). In this paper, only the assessments of theearly alliance are presented. The rater did notknow when the session took place during therapy.This rater and a second rater made independentassessments of 10 sessions with an interraterreliability of r s = 0.58 (P < 0.05).

Intake measures

The Comprehensive Psychopathological RatingScale (CPRS). The CPRS, an interview-basedsymptom scale, was used to evaluate psycho-pathological symptoms (Asberg et al., 1978).

Drug Taking Evaluation Scale (DTES). Byinterview, the severity of abuse, social function-ing, social belonging, and psychic status wereassessed in the four sub-scales of DTES (Holstenand Waal, 1980). These subscales consist of nineoperationally defined steps, where scores 1-3denote normality and higher scores signifyincreasing severity of symptoms or dysfunction.

DSM-III. The patients were asked about thepresence or absence of all items included in thedefinition of alcohol dependence (AmericanPsychiatric Association, 1980).

Problem Drinking Scale (PDS). The PDS is aninterview-based measure of the severity of alco-holism consisting of 16 items (Vaillant, 1983).

The Swedish version of the Alcohol UseInventory (AVI). This is a self-rating question-naire, which is based on the Alcohol UseInventory (Wanberg et al., 1977), and standar-dized on a sample of more than 600 Swedishalcoholics (Berglund et al, 1988).

Outcome measures

Interviews and self-ratings were administeredby independent research assistants 3, 6, 12, 24 and36 months after the start of treatment. In thisstudy, self-ratings of mood at 3, 6 and 12 monthsand measurement of drinking outcome at 6,12 and36 months will be used.

Mood dimensions. A Swedish Mood AdjectiveCheck List (MACL), a self-rating questionnaire(Sjtiberg et al., 1979; BokstrSm et al., 1991),comprising 71 mood-related adjectives groupedinto six bipolar dimensions, was used. Thesedimensions are: pleasantness/unpleasantness(happy, sad, etc.); activation/deactivation (active,drowsy, etc.); extroversion/introversion (talkative,silent, etc.); calmness/tension (calm, nervous,etc.); positive/negative social orientation (coop-erative, unreasonable, etc.); and control/lack ofcontrol (self-confident, insecure, etc.), with thedimensions before the slanting strokes represent-ing positive tones. The dimensions pleasantness/unpleasantness, activation/deactivation and calm-ness/tension are regarded as basic mood dimen-

Dow

nloaded from https://academ

ic.oup.com/alcalc/article-abstract/32/3/241/136456 by guest on 05 April 2019

244 A. OJEHAGEN et al.

sions, whereas the other three dimensions areconsidered to be more closely associated withsocial relations and situations. The presentation ofthe adjectives is randomized. The possible rangefor each dimension is 1—4. A high value denotes apositive tone. The MACL questionnaire wasadministered by the research assistant beforetreatment and 3, 6 and 12 months after the startof treatment.

Drinking outcome. The number of abuse dayswas registered. Abuse days were defined as dayswith a consumption of >4 drinks (1 drink — 3.8 clof 40% liquor) during continuous drinking, or >6drinks on occasional drinking days (Sobell andSobell, 1978).

During the periods of follow-up, the number ofabuse days was used as a measure of drinkingoutcome. The same cut-off points for favourableoutcome as in our previous studies were used(Nordstrom and Berglund, 1987; Ojehagen et al.,1988). A maximum of 7 abuse days at 6 monthfollow-up periods and 14 abuse days during 1 yearfollow-up periods was considered a favourableoutcome.

In this sample, corroboration of positive drink-ing outcome during the third year was made byrelatives and/or through liver enzyme measure-ments (Ojehagen et al., 1992).

Statistics

The Mann—Whitney {/-test was used as a non-parametric test for differences between subgroups,and when appropriate Student's Mest andANOVA were used in the analyses of differencesbetween means. Spearman rank correlations werealso performed. A stepwise logistic regressionanalysis was used in analyses of the relationshipbetween alliance and drinking outcome. Thesoftware used for statistical analyses was SPSSfor Windows, Version 6.0 (Norusis, 1993).

RESULTS

Comparison between the two therapies regardingearly alliance

Multimodal therapy (MBT, n = 17) had sig-nificantly better early therapist alliance in com-parison with psychiatric treatment (PT, n = 18)according to Mann-Whitney 17-test (MBT:mean ± SEM = 67.2 ± 1.0; PT: 61.3 ± 1.0;

P < 0.01). There were no significant differencesbetween the two therapies regarding early patientalliance (MBT: 62.5 ± 1.4; PT: 60.1 ± 1.2).

An ANOVA showed no differences in earlytherapist or patient alliance with regard to lengthof therapy, nor were there any significant interac-tions between mode of therapy and length oftherapy.

Within the respective therapies, there weresignificant correlations (P < 0.001) betweenearly patient and therapist alliance (r$ = 0.81 inMBT and r s = 0.81 in PT).

Early alliance (patient or therapist) was inneither of the two therapies related to socio-demographic data (sex, marital and occupationalstatus), nor initial measures of severity of alcoholmisuse and psychopathology (DTES, PDS, AVI orCPRS) (n = 35).

Early alliance in relation to mood dimensionsduring treatment

There were no significant differences withregard to the six mood dimensions betweenpatients in the two therapies before, or at 3, 6and 12 months after the start of treatment.

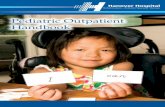

In Fig. 1, correlations are presented betweenearly patient alliance and mood dimensions beforetreatment, and after 3, 6 and 12 months in MBTand PT; Fig. la concerns three basic mooddimensions (pleasantness, activation and calm-ness), and Fig. lb concerns three mood dimen-sions associated with social relations andsituations (extroversion, positive social orientationand control).

In MBT, there were significant positive correla-tions between early patient alliance and threemood dimensions after 6 months (in Fig. la:pleasantness +0.53; in Fig. lb: extroversion+0.48, and control +0.56; P < 0.05). The correla-tions between early therapist alliance and mooddimensions were similar to the correlationsbetween mood and early patient alliances, butdid not reach a significant level [in MBT thetherapist correlations to basic mood dimensionswere: pleasantness +0.27, activation +0.09,calmness +0.16; and to mood dimensions asso-ciated with social relations and situations: extro-version +0.31, positive social orientation +0.14,control +0.32 (not significant)].

Dow

nloaded from https://academ

ic.oup.com/alcalc/article-abstract/32/3/241/136456 by guest on 05 April 2019

HELPING ALLIANCE AND OUTCOME IN ALCOHOLISM TREATMENT

0,6 i .

245

0 4

0.0

-0.2

A- o-

A"

(a)6

Months12

O Pleasantness - PT D Activation - PT A Calmness - PT• Pleasantness - MBT • Activation - MBT A Calmness - MBT

0.6 r

i-O.20- •

(b)

6Months

O Extroversion - PT• Extroversion - MBT

• Positive social orientation - PT• Positive social orientation - MBT

A Control - PTA Control-MBT

Fig. 1. (a) Correlations between early patient alliances and basic mood dimensions.Dimensions (pleasantness, activation, calmness) were assessed at the start of treatment and after 3, 6 and 12 months in

multimodal behavioural therapy (MBT) and psychiatric treatment (PT). There was a significant positive correlation after 6months in MBT between alliance and pleasantness (P < 0.05).

(b) Correlations between early patient alliances and mood dimensions associated with social relations and situations.Dimensions (extroversion, positive social orientation and control) were assessed at the start of treatment and after 3, 6

and 12 months in multimodal behavioural therapy (MBT) and psychiatric treatment (PT). There were significant positivecorrelations after 6 months in MBT between alliance and extroversion and control (P < 0.05).

Early alliance in relation to drinking outcomeIn Table 1, correlations between early patient

and therapist alliances and drinking outcome inthe first and second half-year, and in the third yearafter start of treatment are presented separately for

MBT and PT. There were no significant positivecorrelations between early alliances and drinkingoutcome. Some correlations were, however,strongly negative. A stepwise logistic regressionanalysis with alliance and psychiatric status as

Dow

nloaded from https://academ

ic.oup.com/alcalc/article-abstract/32/3/241/136456 by guest on 05 April 2019

246 A. OJEHAGEN et al.

Table 1. Spearman rank correlations between eariy patient and therapist alliances in drinking outcome

Drinking outcome

First half-yearSecond half-yearThird year

Patient

-0.42-0.04-0.52»

MBT (n = 17)Eariy alliance

Therapist

-0.210.02

-0.23

Patient

-0.08-0.25-0.23

PT (n = 18)Early alliance

Therapist

-0.14-0.39-0.44

Correlations were applied for the above measures in the first and second half-year, and in the third year after start oftreatment in multimodal behavioural therapy (MBT) and psychiatric treatment (PT).

*P < 0.05.

independent variables was also performed, whichshowed no significant associations with drinkingoutcome.

Correlations between mood dimensions anddrinking outcome during the first year

Correlations between drinking outcome in thefirst half-year and mood dimensions at 6 months,and between drinking outcome in the second half-year and mood dimensions at 12 months, in MBTand PT respectively, in all 24 correlations, wereperformed. In PT, there was a positive correlationbetween drinking outcome in the first half-yearand activation at 6 months (+0.48, P < 0.05),whereas other correlations were positive but notsignificant. The correlations in MBT were gen-erally low.

DISCUSSION

When interpreting the results of the presentstudy, some shortcomings should be kept in mind.The sample groups were too small for drawingsafe conclusions. The attrition from treatment isanalysed in a previous article (Ojehagen et al.,1992). In the present paper, we focused onalliance in relation to outcome among treatmentcompleters. An intention-to-treat analysis of allsubjects randomized would give additionalaspects on the importance of alliance. This willbe analysed in a separate paper. In randomizedtreatment studies, some patients probably will bemismatched, and therefore it would be especiallyinteresting to investigate alliance in relation toattrition. Furthermore, the therapist factor is notstandardized; there were no treatment manuals

and the number of therapists differed between thetwo treatment types. A greater number oftherapists should perhaps have been used toprevent confounding of therapist effects with thecomparison of MBT with PT. In particular, thesingle therapist in MBT confounds therapisteffects with the treatment effect. However, ourfindings of a better alliance in MBT are inaccordance with another recent study, thus point-ing to a positive relationship between alliance andMBT beyond the therapist factor (Raue et al.,1993). The interrater reliability of the helpingalliance was only performed in a few patients, andcorrelation coefficients were rather weak. Finally,this study recruited socially stable alcoholics, with74% being married or cohabiting and 68%regularly employed, and it is reasonable to assumethat our findings are representative only ofsocially stable alcoholics.

In this randomized study, comparisons of help-ing alliance between two long-term alcoholismtreatment models were performed that have notbeen presented previously. Both mood and drink-ing outcome were assessed several times, whichfurther strengthens the design.

Our main results were that early therapistalliance was better in MBT in comparison withPT. A significant positive correlation was shownbetween early patient alliance and mood dimen-sions at 6 months in MBT. There were nosignificant positive correlations between earlyalliance and drinking outcome.

A better alliance in cognitive and behaviouraltherapy in comparison with psychodynamic-inter-personal therapy has recently been reported (Raueet al., 1993), and might be explained by

Dow

nloaded from https://academ

ic.oup.com/alcalc/article-abstract/32/3/241/136456 by guest on 05 April 2019

HELPING ALLIANCE AND OUTCOME IN ALCOHOLISM TREATMENT 247

differences in therapist style and treatment struc-ture. These differences, also present in our study,were however not related to drinking outcome inthe whole sample (Qjehagen et al., 1992).

One difference between MBT and PT concernsthe timing of treatment, i.e. in MBT mosttreatment sessions took place during the first halfof the treatment period with booster sessionsthereafter, whereas sessions were individuallydistributed in PT. There were to be 30 sessionsin both treatment programmes, and the finalnumber of sessions did not differ between thetherapies (Qjehagen et al., 1992). The meta-analysis including 20 alliance studies performedby Horvath and Symonds (1991) found nocorrelation between alliance and treatment length(6—52 sessions). The early alliance differencesconcerned therapist alliance only, which maymirror the more active approach of MBT, andwhich might have influenced the level rating ofthe MBT therapist alliance.

Behavioural cognitive therapy techniques havebeen shown to be more successful than dynami-cally-orientated therapies in subjects with a moresevere psychopathology/sociopathy and vice versa(Cooney et al., 1991; Litt et al., 1992). Similarresults have been found in this study, i.e. in PTpatients a favourable drinking outcome in the thirdyear was more strongly related to a betterpersonality structure (i.e. DTES scores < 3 ,which denotes normality) than in MBT patients(Qjehagen et al., 1992). In comparison with PT,which was based on a psychodynamic approach,the MBT programme focused on finding copingstrategies, which may apply more to patients witha less good personality structure. These patientsare often in need of strong support and structure,which might partly explain the positive correlationbetween early patient alliance and mood at 6months in MBT patients. Perhaps also techniquesin building a good alliance are more apparent inbehavioural-orientated therapies. Gaston (1990)reported that, within treatment conditions, thealliance uniquely contributed to outcome, with anincreasing variance accounted for as the therapyprogressed, especially in behaviour and cognitivetherapy as compared to brief dynamic therapy. InMBT treatment, alliances and mood outcomeduring treatment had no relation to favourabledrinking outcome.

In the present study, no positive relations of

early alliance with favourable drinking outcomeduring the first and second half-year, or in thethird year in any of the treatment programmeswere found. On the contrary the correlation todrinking outcome in the third year was signifi-cantly negative in MBT. Thus, the predictivevalue of early alliance to outcome reported fromother studies could not be corroborated. Thesestudies mostly concerned psychotherapy and weremostly not evaluated in a long-term perspective. Inmodem alcoholism treatment studies, a follow-upperiod of 2 years after start of treatment iscommon, since stability of improvement is ofimportance. The negative correlation ought to bereplicated in further studies. Maybe alliance earlyin therapy is not predictive of drinking outcome incomparison with other determinants of outcome.Factors influencing alliance, i.e. patient character-istics and therapy technique remain to be furtherinvestigated (Henry et al., 1994).

Luborsky et al. (1985) analysed the alliance inmethadone-maintained drug dependent patientsand found significant positive correlationsbetween alliance and a number of outcomemeasures at 7 months, including drug use,employment status, and psychological functioningaccording to ASI (Addiction Severity Index).Methadone-maintenance therapy is a highly struc-tured treatment with daily administration ofmethadone, and is a considerably less intenseform of alcoholism treatment (1-2 sessions/month); this could be one explanation for thedivergent results.

Another difference between our study and thatby Luborsky et al. (1985) concerns the method ofrating the helping alliance. In Luborsky's studythe therapists and patients rated the alliance afterthe third session, whereas in our study the ratingswere made by an independent researcher based ontape-recordings. The drinking outcome measure inour study also differs, i.e. our measure of drinkingoutcome is categorical, favourable versus unfa-vourable, unlike the ASI measure used byLuborsky.

Horvath and Symonds (1991) found that clients'and observers' ratings of alliance appeared to bemore correlated with all types of outcomesreported than therapists' ratings. In general, thealliance measures appear to better predict out-comes tailored to the client (i.e. target complaints)than broad-range symptomatic change (Horvath

Dow

nloaded from https://academ

ic.oup.com/alcalc/article-abstract/32/3/241/136456 by guest on 05 April 2019

248 A. OJEHAGEN et al.

and Symonds, 1991).Furthermore, the process of improvement con-

cerning alcohol misuse and improvement in otherareas is not clearly known (Ojehagen et al., 1986).For example, in this study, mood during treatmentwas only to some degree related to drinkingoutcome during treatment, but not to outcome inthe third year after start of treatment.

Apparently helping alliance is positively corre-lated to mood after 6 months, especially in certaintypes of therapy. This is of importance in under-standing different treatment processes of change.Therefore the relationship of alliance to patients'mood during alcohol treatment, and the relation ofmood to drinking outcome (Bokstrom et al., 1991)should be addressed in further studies.

In conclusion, the relationship between earlyalliance and improvement in alcohol misuse needsto be further investigated. An initial good allianceseems insufficient to reduce alcohol misuse. Theabsence of a positive relationship between allianceand drinking outcome stresses the need for furtherinvestigations of the process of change inalcoholism treatment.

Acknowledgements —This study was supported by TheSwedish Council for Planning and Coordination ofResearch, The Swedish Council for Social Research, TheSwedish Medical Research Council and funds from LundUniversity.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnosticand Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rdedn. American Psychiatric Association, Washington,

. DC.Asberg, M., Montgomery, S. A., Penis, C, Schalling, D.

and Sedwall, G. (1978) A Comprehensive Psycho-pathological Rating Scale. Ada Psychiatrica Scan-dinavica, Supplementum.

Berglund, M., Bergman, H. and Swenelius, T. (1988)The Swedish Alcohol Use Inventory (AVI), a self-report inventory for differentiated diagnosis inalcoholism. Alcohol and Alcoholism 23, 173-178.

Bokstrom, K., Balldin, J. and LSngstrdm, G. (1991)Individual mood profiles in alcohol withdrawal.Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research15, 508-513.

Cooney, N. L., Kadden, R. M., Litt, M. D. and Getter, H.(1991) Matching alcoholics to coping skills orinteractional therapies: Two-year follow-up results.Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology 59,598-601.

Gaston, L. (1990) The concept of the alliance and itsrole in psychotherapy: theoretical and empirical

considerations. Psychotherapy 27, 143-153.Henry, W. P., Strupp, H. H., Schacht, T. E. and Gaston,

L. (1994) Psychodynamic approaches. In Handbookof Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 4th edn,Bergin, A. E. and Garfield, S. L. eds, pp. 467-508.Wiley, New York.

Holsten, F. and Waal, H. (1980) The Drug TakingEvaluation Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica61, 275-305.

Horvath, A. O. and Luborsky, L. (1993) The role oftherapeutic alliance in psychotherapy. Journal ofConsulting Psychology 61, 561-573.

Horvath, A. O. and Symonds, B. D. (1991) Relationbetween working alliance and outcome in psy-chotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of ConsultingPsychology 38, 139-149.

Lazarus, A. A. (1981) The Practice of Multi-modalTherapy. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Litt, M. D., Babor, T. F., DelBoca, F. K., Kadden, R. M.and Cooney, N. L. (1992) Types of alcoholics, II.Application of an empirically derived typology oftreatment matching. Archives of General Psychiatry49, 609-614.

Luborsky, L. (1984) Principles of PsychoanalyticPsychotherapy. A Manual for Supportive ExpressiveTreatment. Basic Books, New York.

Luborsky, L., McLellan, T., Woody, G. E., O'Brien, C.P. and Auerbach, A. (1985) Therapist success and itsdeterminants. Archives of General Psychiatry 42,602-611.

Morgan, R. W., Luborsky, L., Crits-Christoph, P. et al.(1982) Predicting the outcomes of psychotherapy bythe Penn Helping Alliance rating method. Archivesof General Psychiatry 39, 397-402.

Nordstrom, G. and Berglund, M. (1987) Type 1 and type2 alcohoh'cs (Cloninger & Bohman) have differentpatterns of successful long-term adjustment. BritishJournal of Addiction 82, 761-769.

Norusis, M. J. (1993) SPSS for Windows, 6.0. SPSS Inc.,Chicago.

Ojehagen, A., Skjaerris, A. and Berglund, M. (1988)Prediction of posttreatment drinking outcome in a 2-year out-patient alcoholic treatment program. Afollow-up study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experi-mental Research 12, 46-51.

Ojehagen, A., Berglund, M., Appel, C.-P., Nilsson, B.and Skjaerris, A. (1991) Psychiatric symptomsin alcoholics attending outpatient treatment.Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research15, 640-646.

Ojehagen, A., Berglund, M., Appel, C.-P., Andersson,K., Nilsson, B., Skjaerris, A. and Toftenow-Wedlin,A.-M. (1992) A randomized study of long-termoutpatient treatment in alcoholics. Psychiatric treat-ment versus multimodal behavioral therapy, and 1versus 2 years of treatment. Alcohol and Alcoholism27, 649-658.

Raue, P. J., Castonguay, L. G. and Goldfried, M. R.(1993) The Working Alliance: a comparison of twotherapies. Psychotherapy Research 3, 197-207.

SjSberg, L., Svensson, E. and Persson, L.-O. (1979) Themeasurement of mood. Scandinavian Journal of

Dow

nloaded from https://academ

ic.oup.com/alcalc/article-abstract/32/3/241/136456 by guest on 05 April 2019

HELPING ALLIANCE AND OUTCOME IN ALCOHOLISM TREATMENT 249

Psychology 20, 1-18. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA andSobell, M. B. and Sobell, L. C. (1978) Behavioral London.

Treatment of Alcohol Problems. Plenum Press, New Wanberg, K. W., Horn, J. L. and Foster, M. F. (1977) AYork. differential assessment model for alcoholism. The

Vaillant, G. E. (1983) The Natural History of Alcohol- scales of the alcohol use inventory. Journal ofism. Causes, Patterns and Paths to Recovery. Studies on Alcohol 38, 512-543.

Dow

nloaded from https://academ

ic.oup.com/alcalc/article-abstract/32/3/241/136456 by guest on 05 April 2019