The Relationship Between Form and Formlessness in Mandalas (Sung Min Kim)

-

Upload

tera-gomez -

Category

Documents

-

view

168 -

download

4

description

Transcript of The Relationship Between Form and Formlessness in Mandalas (Sung Min Kim)

-

The Relationship Between Form and Formlessness

in Mandalas

Interpreting the Aesthetic Power of Buddhist Mal}qaias

on the basis of the philosophy of vlik in Trika Saivism

A Thesis submitted to Jawaharlal Nehru University for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

In

Arts & Aesthetics

Sung Min Kim

School of Arts & Aesthetics

Jawaharlal Nehru University

New Delhi-ll0 067

2008

-

24th Jan. 2008

Declaration by the Candidate

This thesis titled "The Relationship Between Form and Formlessness in MalJtjalas:

Interpreting"the Aesthetic Power of Buddhist MalJtjaias on the basis of the philosophy

of viik in Trika Saivism" submitted by me for the award of the degree of Doctor of

Philosophy, is an original work and has not been submitted so far in part or in full, for

any other degree or diploma of any University or Institution.

Ph. D. student School of Arts & Aesthetics Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi

-

School of Arts & Aesthetics JAWAHARLAl NEHRU UNIVERSITY

New Delhi- 110 067, India

Certificate

Telephone: 26742976, 26704177 Telefax: 91-11-26742976 E-mail: [email protected]

This is to certify that the thesis entitled, "The Relationship Between Form and

Formlessness in Ma'!4a1as: Interpreting the Aesthetic Power of Buddhist Ma1Jqalas on

the basis of the philosophy ofviik in Trika Saivism", submitted by Sung Min Kim, the

School of Arts & Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, for the award

of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, is her own work and has not been submitted so

far in part or in full for any other degree or diploma of this or any other university.

We recommend that this thesis be placed before the examiners for evaluation.

s' ...... ~ .. -. '_A f> ~ -' .- '-' ',' ,; . ;,S: '(F ,',i=.< 4 .... ::. - fcs

Proi!:B~:E>av~:MtikhgijF' 3ity (Dean)

Prof. H. S. Shivaprakash (Supervisor)

-

Prologue

It was fifteen years ago when I witnessed the great ritual of Heruka ma1Jrjala in

Leh, t~e centre of Ladakh in India in 1992. I was then an art student, and my trip to India was triggered by a very vague question about the meaning of artistic creations. My

encoun~er with the ritual of the ma1Jrjala was unexpected, and indeed overwhelming. First of all, the ritual of the ma1Jrjala that was accompanied by the mantra recitation and

the mu.dras had shaken my senses with their strong aural and visual powers. I was enraptured in the current of colourful visuals and penetrating sounds throughout the ritual that continued more than a week. Above all, the final dissolution of the ma1Jrjala

into a flowing river after such an elaborate ritual around the building-up of the colourful

forms seemed to have given me the answer why I had to travel in India: I thought I have

seen t~e true form of arts. The impression of the ma1Jrjala ritual was so strong that I wanted to write an essay about it, when I returned to Korea. However, I could not h,!-ndle the topic in spite that I had written down the notes with technical descriptions during the ritual. The subject was too formidable to be dealt with in an essay. Moreover I did not have even an idea about the background and the philosophy of the ma1Jrjala.

However, my perspnal experience of the ma1Jrjala spoke itself about the profundity of

the ma1Jrjala. I started looking up the books to know about their symbolic and religious

meanil1;gs. During my M.A. study, when I was mainly concerned with the question of

the relation between the concepts and the forms, I attempted to write about the ma1Jrjala

for the M.A. dissertation. Even though I had learnt some symbolic meanings of the ma1Jrjala, they were too fragmentary to give me the confidence that I had learnt

anythil1g. At the same time, I had been influenced by the idea of 'the meaninglessness of the ritual', which seemed to tell me that knowledge of some symbolic meanings of the

ma1Jrjala ritual is futile.

Finally, I present my understandings of the ma1Jrjala in the form of a Ph. D. thesis

carri,eq, qut under ~he supervision of Prof. H.S. Shivaprakash in the School of Arts & Aestl)eti~s, lawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. He~e, I deal with the visual forms of ma1Jrjalas and their meaning beyond the religious or symbolic meanings. Since

-

my interest on the ma1'}tjaia started from the overwhelming experience when I had no

knowledge of the ma1'}tjaia, my thesis focuses on the question about the nature and

aesthetic power of the ma1'}tjaia that is conferred to the viewer during the aesthetic

experi~nce. It is only thanks to Prof. H. S. Shivaprakash that my quest for the mea~iI1gful visuals has been encouraged and possibly taken into the fruit of thesis.

I must above all express gratitude for the help and critical comments received from

Dr. EI1J&t FUrlinger. From the initial stage of the conception till the final refinement of

the ~i~ings, he shared his knowledge about the subject and provided me with treasuries of research sources. Conversations with him stimulated me to carryon the research with

enthus~a,sm and gave me the chance to look at the subject from the different angles .. His critical comments helped me in organizing my fragmentary thoughts into a structure., I

thank Dr. Bettina Baumer in having read through my unripe synopsis and given me helpful ,?omments. Also, I must express thankfulness to her for introducing the field of

Trika Saivism to Il)e and for helping me out in comprehending the verses from the old texts. I must equally express my gratefulness to Dr. Christian Luczanits for giving me a

number ofpractica,l guidance in regard to the researches on the sites ofTabo and Alchi. I appreciate his scholarly quality and great generosity that was proved by his de~ailed comm~nts on my unorganized draft. I am grateful to Prof. Lokesh Chandra for his generous help in the matter of textual understanding of Buddhist ma1'}tjaias. He

generously shared his erudition and years of researc~es on the ma1'}tjaias. I should not forget to thank th,e late Prof. Ramachandra Gandhi for helping me in relating my research with the creative activity of paintings. His questions about my paintings and academic interest stirred me to bring forth the question about the relationship between forms and the formless from the dormant state of the consciousness. I thank Dr. Kapila Vatsyayan whose presence and writings have been a continuous inspiration for my research. I thank Dr. Lolita Nehru for teaching me how to write and how to organize ideas.

I must express my gratefulness to Geshe Tsewang Dorje of the Ngari Institute of Buddhi,st Dialectics in Ladakh for accepting my request for the personal teaching on the practic~ pf tantric visualization. His compassionate teachings were extremely helpful in understanding the descriptions of the practice given in the old texts. I also thank Genla

11

-

Takpa Jigmet of the Spituk monastery for sharing his understanding of visualization. I

thank monks of the Tabo monastery, especially Lama Urgyen Angrup for explaining me

the revived ritual of Vajradhatumru;

-

Contents Page No.

Prologlle Contents iv List of Plates vii List of Tables and Illustrations x Abbreviations xii

Introduction 1

Part I

Perceptible Forms and Symbolic Meanings of Buddhist Ma1Jt/aias

Contents of the Part I 1. Examining Bud,dhist Ma1Jt/aias of Tabo and Alchi on the basis of

graphic and textual sources 1.1. Vajradhatu~m~9a1as 1.2. Dharmadhatu-VagIsvara maQ9alas 1.3 .. Mm:ujaias, in the Sumtseg of Alchi: a combined form of architectural and

painting ma1}ejaias 104. Relationship between textual sources and graphic ma1}ejaias

2. Symbolism 2.1. What we learn from the doctrinal expositions of ma1Jejaias 2.2. Entrance to the ma1}ejala ground 2.3. Divinitie~ of the ma1}fjalas of Yogatantras 2.4. Symbolic association of ma1}ejalas with the Buddhist notions of

trikiiya and triguhya

3. Levels of Forms implied in the Discourses on Ma1Jt/aias 3.1 ;What characterizes the form of ma1}ejaias? 3.2. Dimensions of Colours in ma1}ejalas 3.3. Levels of Forms as revealed in the discourses of Buddhaguhya

4. Practice of Visualization 4.1. Description of Visualization 4.2. Concepts extracted from the visualization

iv

23

27 28 42

50 61

66 66 67 69

80

84

84 85 90

97 97

102

-

5. Non-dualism of Forms and the Formless in the Practice and Th_eory of Ma1J4alas

5 .1. Non-dualism of forms and sunya 5.2. Transformation of sunya into perceptual ma1Jq.a/as

6. Summary and Questions

Part II

107 107 111

112

Viik: Transformation between the Perceptible and the In-perceptible

Contents of the Part II 116 1. Association of ma1J4alas with the concept of vak 120

1.1. Tantric Background of ma1Jq.a/as 120 1.2. Buddhist practice of syllables 123 1.3. Tantric conception of the Highest Divinity in the nature of sound 127 1.4. Association of the Goddess Prajiiaparamita in Alchi with viik 135

2. The Doctrine of Vak in Trika Saivism 147 2.1. General Survey of Viik 147 2.2. Introduction to the Four Levels of Viik 151 2.3. Studies of the Four Levels of Viik 156

3. Vak in Mantra Practice 186 3.1. Hierarchic Levels among Mantras 186 3.2. Oly! Ucciira 188

4. Pariiviik and S/l.nya 193 4.1. Referenc~s to Sunya in the Trika Philosophy 193 4.2. Pariiviik in comparison with the notions of the Absolute in

Vijiianavada Buddhism 200 5. The Doctrine of Vak as a Theoretical Basis for Understanding the

Aesthetics of Ma1J4alas 214 5.1. Non-dualism of the two poles in the doctrine ofviik 214 5.2. Why are ma1Jq.a/as distinguished from ordinary visuals? 217 5.3. Three forms ofvaikharf, madhyamii andpasyantf

: sthUla, sukma and para 220 5.4. Transformation of forms explicated in the doctrine ofviik 223

6. Conclusion 231

v

-

Part III

Aesthetic Power and Spirituality of the Visuals of Buddhist Ma1}4aias

ConteI!ts of the Part III 1. R~ddinition ofma1J4alas from the perspective ofthe vok theory.

1.1. What themGlJ4ala is and what is meant by the marp!ala : vacaka and vacya

1.2. The problem of the vacya and the vacaka in malJtjalas

2. Ma1Jt/alas of Alchi interpreted as the gross form ofpaJyantTvllk 2.1. Nature ofJhe Pasyantf vak 2.2. Speculation on the exposition of the Sthil/a Pasyantf 2.3: MGl:uJa/as,and nada

3. Visu,al elements of the gross paJyantT: How are ma1Jt/alas of Alchi the gr.oss form of paJyantl?

3.1. Large scale of the malJtja/as enfolding the viewer 3.2. Geometric Layout 3.3. Geometric Basis of Figures 3.4. Sensuousness of Distinct Parts 3.5. Five Primary Colours and Their Multiple Tones 3.9. Conclusio,n: The Fusion of the Distinct and the Indistinct

in the MalJtjalas of Alchi

4. Aest~etic Power of the ma1Jt/alas of Alchi 4.1. Aesthetic power: the sthUla pasyantf in resemblance to the Divine

Consciousness 4.2~ Determinants of the Aesthetic experience of MalJtjalas 4.3. Spirituality of Aesthetic Seeing of MalJtja/as 4.4. Conclusion: Spirituality of Aesthetic Perception of MalJtjala

Conclusion

Bibliography

vi

234 236

236 238

241 241 243 246

249 250 252 270 285 289

293

296

296 297 299 308

309

313

-

List of Plates'"

1. Sumtseg as a tiu:ee-story stupa, Alchi 2. Valr~dhatu-mwtC;lala, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 3. Mahavairocana, Vajradhatu-mwtC;lala, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo. 4. Ak~obhya of the Vajradhatu-mwtC;lala, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 5. An)itabha of the Vajradhatu-mwtC;lala, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 6. Panel of Amitabha, over the entrance doorway of the dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang,

Tabo 7. Vaj,radhatu-mwtC;lala, dukhang, Alchi 8. Inner zone, Vajradhatu-mwtC;lala, dukhang, Alchi 9. Ak~obhya chamber, Vajradhatu-maQC;lala, dukhang, Alchi 10. Ratnasarp.bhava chamber, Vajradhatu-mwtC;lala, dukhang, Alchi 11. Amitabha chamber, Vajradhatu-mwtC;lala, dukhang, Alchi 12. Amogasiddhi chamber, Vajradhatu-maQC;lala, dukhang; Alchi 13. Dharmadhatu-VagIsvara-mwtC;lala, partial view, dukhang, gTsug.;.lag-khang, Tabo 14. Central divinity, Dharmadhatu-VagIsvara-mwtC;lala, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang,

Tabo 15. Four U~QI~as, Amitabha, Amoghasiddhi, PaQC;lara and Tara, Dharmadhatu-

VagIsvara-mwtC;lala, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 16. Ak~obhya, Dharmadhatu-VagIsvara-mwtC;lala, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 17. Ratnasarp.bhava, Dharmadhatu-VagIsvara-maQC;lal?, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang,

Tabo 18. MamakI, Dharmadhatu-VagIsvara-mwtC;lala, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 19. Locana, Dharmadhatu-VagIsvara-mwtC;lala, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 20. Dharmadhatu-vagIsvara-mwtC;lala, dukhang, Sumda 21. Dharmadhatu-vagisvara-mwtC;lala, dukhang, AI~hi 22. Stupa, interior, sumtseg, Alchi 23. Maitreya, sumtseg, Alchi 24. Avalokitesvara, sumtseg, Alchi 25. MafijusrI, sumtseg, Alchi 26. Sakyamuni's life painted on the dhoti of Maitreya, sumtseg, Alchi 27. Scenes on the dhoti of Avalokitesvara, sumtseg, Alchi 28. Siddhas' yogic practices painted on the dhoti of Mafijusn, sumtseg, Alchi 29. Ak~obhya on the right side of the Maitreya's alcove, sumtseg, Alchi 30. Mafijusn on the left side of the Maitreya's alcove, sumtseg, Alchi

vii

-

, 31. Ak.50bhya surrounded by his miniature images, Maitreya's alcove, sumtseg, Alchi 32. Amitabha surrounded by his miniature images, Avalokitesvara's alcove, sumtseg,

Alchi 33. Prajnaparamita as Tara, on the left wall of the Avalokitesvara's alcove, sumtseg,

Alqhi 34. M41iature images of Maiijusn, ManjuSn's alcove, sumtseg, Alchi (published in the

G~Rper & Poncar 1996, p. 96) 35. Sakyamuni Buddha as Vairocana over the Maitreya's alcove, second story, sumtseg,

Alchi 36. Prajn,aparamita as Mahavairocana and Five Buddhas, rear wall, second story,

sWl,ztseg, Alchi.(published in the Goepper & Poncar 1996, Pl" 168-9) 37. Fiv.e, Buddhas in their particular paradises, rear w~l, second story, sumtseg, Alchi 38. Ma1J{j.ala (M 1). left side of the left wall, second story, sumtseg, Alchi 39. Ma1Jrj.ala (M 2), right side of the left wall, second story, sumtseg, Alchi 40. Vajrl:lsattva and two Buddhas in feminine appearance, ma1Jfj.ala (M 4), right side of

the. rear wall, second story, sumtseg, Alchi 41. M01Jtj.ala (M 5), left side of the right wall, second story, sumtseg, Alchi 42. Ma1Jfj.ala (M 6), right side of the right wall, second story, sumtseg, Alchi (published

in the Goepper .& Poncar 1996, p. 200) 43. Ma1J{j.ala ofM~jusn, rear wall, third story, sumtseg, Alchi 44. CeJ)~al divinity, ma1Jfj.ala of Mafijusn, rear wall, third story, sumtseg, Alchi 45. M.a1J.4ala of Mahavairocana, left wall, third story, sumtseg, Alchi 46. Central divinity, ma1Jfj.ala of Mahavairocana, left wall, third story, sumtseg, Alchi

(published in the Goepper & Poncar 1996, p. 219) 47. Ma1Jq.ala of Prajiiaparamita, right wall, third story, sumtseg, Alchi (published in the

Goepper & Poncar 1996, p. 221) 48. Cen~al divinity, Ma1Jfj.ala of Prajiiaparamita, right wall, third story, sumtseg, Alchi

(puplished in the Goepper & Poncar 1996, p. 220) 49. City. walls and gates in the narrative scenes of Sudhana's Pilgrimage, dukhang,

gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 50. Nru:rative scene depicting Sudhana's meeting with the master RatnacuQa, dukhang,

gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 51. Prajiiaparamita as Mahavairocana, rear wall, second story, sumtseg, Alchi (published

in the Goepper & Poncar 1996, p. 169) 52. Prajiiaparamita-ma1Jfj.ala, dukhang, Alchi 53. Central image, Prajiiaparamita-ma1Jfj.ala, dukhang, Alchi

viii

-

54. Prajfiaparamita-ma1J4ala, interior of the small twin-stupa, Alchi 55. Prajfiaparamita-ma1J4ala, Maitreya Hall, Mangyu 56; Central camber, Prajfiaparamita-ma1J4ala, Maitreya Hall, Mangyu 57. Zen drawing ofa circle, Seokjeong, 1980 (published in Choi 1998, p. 217) 58. Yantra of the goddess ChamUl:u;la, Rajasthan, 19th cent. Ink and colour on paper

(pubFshed in Khanna 1979, p. 45) 59. Small twin-stupa, in front of the sumtseg, Alchi 60. Inner stupa, small twin-stupa, in front of the sumtseg, Alchi 61. Mahavairocana chamber, Vajradhatu-maQQala, dukhang, Alchi 62. Tara chamber, Vajradhatu-maQQala, dukhang, Alchi 63 ~ Ma1J4ala, left wall, dukhang, Mang)"J

. 64.'Image painted over the Sudhana's Pilgrimage, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 65: Central image of the ma1J4ala (M 6), right wall, second story, sumtseg, Alchi 66. 'Wave lines and 'spiral patterns painted on the halo, Vajrahasa, Vajradhatu-maQQala,

. south wall, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 67\ Panel ofSaradhvaja, Sudhana's Pilgramage, dukhang, gTsug-lag-khang, Tabo 68. Repainted image, central chamber of the ma1J4ala (M 3), left wall, second story,

smntseg, Alchi \.

* The plates without the indications of the original publications in the above list have been given permission to publish in the thesis by the Western Himalayan Archive of Vienna (WHAV).

ix

-

List of Tables and Illustrations

[Ill. 1] Ground plan of the monastic complex of Tabo (C. Luczanits, based on a plan from Iqlosla 1979, p. 38; illustrated in Klimburg-Salter 2005, p. 9) [Ill. 2] Basic plan of the Dharmadhatu-Vagrsvara m~4ala in the dukhang, Alchi [Ill. 3] Ma1)#llas in the second story of the sumtseg in Alchi [Ill. 41 Dynamism.between Mahavairocana and Prajiiaparamita in the two ma1)fjalas of the third story of the sumtseg [Ill. 51* Drawing process of the geometric layout of the Guhyasamaja-m~4ala (il~ustrated by Don~'grub-rDo-rje in Rong-tha Blo-bzani-dam-chos-rgya-mtsho 1971) [Ill. 6] Analysis of the basic compositional lines in the inner zone of the Vajradhatu-mru;t4ala in the dukhang, Alchi [Ill. 7] Analysis of the basic compositional lines in the inner zone of the Vajradhadu-m~r;t4ala based on the references from the Vajravali (the ma1)fjala published in Chandra & Vira 1995, p. 63) [Ill. 8] Analysis of the compositional lines in the central chamber of the Vajradhatu-mar;t

-

[Table 6] Symbolic layers of Five Primary Colours as given in the Mahlivairocana-abJ,isaf!lbodhi Tantra

[Table 7] Correspondence between the four levels ofviik, three saktis and five saktis. [Table 8] Correspondence between the twelve stages of O ucciira and the four levels ofviik

xi

-

Abbreviations

OhA Dhvanyiiloka VV Vajriivali OhAL Dhvanyiilokalocana YRM Yogaratnamiilii OMS Dharmama1J4ala Sutra YH Yoginihrdaya HT Hevajra Ta~tra IPK !svarapratyabhijiiiikiirikii IpV /svarapratyabhijiiiivivrti Ipvv !svarapratyabhijiiiivivrtivimarsini LS Lankavatara Sutra MV Madhyiintavibhiiga MVBh Madhyiintayibhiigabhii~ya MVT Mahiivairocaniibhisafllbodhi Tantra NS Niimasafllgi1i NSP Ni~pannayogiivali NT Netra Tantr.a PHr Pratyabhijiiiihrdayam PS Pramiil:wsamuccaya PTV P ariitris ikii- Vivara1)a RGV Ratnagotravibhaga SO Sivadr~!i SM Siidhanamiilii SDPT Sarvadurgatiparisodhana Tantra SpK Spandakiirikii SpY Spandavivrti SS Sivasutras SSV Sivasutravimarsini ST Siiradii Tilaka STTS Sarvatathiigatatattvasafllgraha SvT Svacchanda Tantra TA Tantriiloka TrK Trirrzi ikii~kiirikii TS Tattvasafllgraha VBh Vijiiiina Bhairava VP Viikyapadiya VSU Viistusutra Upani~ad

xii

-

Introduction

The central question of the thesis is about the relation between visual forms and their inlaid meanings in a broad context. The research undertaken here is basically meant f9r exploring the metaphysical dimension of visuals with the question how the visible qimensions of forms are related to their invisible dimensions. The metaphysical

dimen~ions of visual forms are experiential, and their vital presence unfolds in the process of creatio~ or aesthetic relish. While we discuss about the inlaid meanings of visual forms, we are naturally confronted with the questions: what do we mean by the inlaid ~eanings? Are they symbolic meanings? Or, metaphoric meanings? From the preset, it should be discerned that there is a non-discursive meaning as well as discursive meanings that are charged in visual forms. 1 The non-discursive layer of visual forms may be illustrated by artists' inspirations ;that result in the creation of forms. Then, what are the relationships between the non-discursive layer and the discursive layers of visual forms? For the purpose of investigating into the nature of forms and their relationship to the formless source of the forms, the thesis focuses on Buddhist

ma,!q.alas, because they are profound and multi-layered in contents as much as they are

elaborate and affluent in forms. The term ma,!q.ala designates different objects accordi,ng to the context of references. It may refer to the system of bodily cakras where deities r~side; or the secret ritual meeting of tantric initiates and yoginis (melaka) where the partiCipants usually form a circle; or the ritual ma,!q.ala seen during the initiation; or

the ,one perceived in one's body in the process of tantric yoga. The ma,!q.ala considered

in the thesis is limited to those visual objects permanently represented in the monastic complex and seen by the public during the worship.

The Question of the Relationship between Forms and the Formless

In regard to the topic, the relationship between forms and the formless, let us consider some examples, before the problem of form and the inner contents of ma,!q.alas is to be

looked at. Somebody sees the contradiction in Buddhists' bowing down in front to the

1 Langer calls it 'essential import'. See Langer 1953: pp. 373-4.

1

-

Buddhc:t images and says that the Buddha resides in one's own mind not in the images.

However, it is not the physical form, but the spirit of the Buddha to which devotees bow down. The physical form of the Buddha is placed at the altar in order to remind people of the bodhicitta in their mind. Among the Buddhist cOIl1lllunity of East Asia, the portrait of Bodhidharma, who is the first patriarch of Zen tradition, is revered and

believ~d to have a spiritual power. Thus, monk painters of the Zen tradition often draw his por.traits. When they draw his portrait, it is not the beautiful face of Bodhidharma but the s,r.irit imbu~d in his face that they challenge to draw. These two examples typify the tru~ meaning of visual forms lying in the expression of what is formless. If we talk about th~ form in the. context of Buddhism, first of all, we are reminded of the great

affirm~tion: 'the rupa (form) is the sunya (void), and the sunya is the rupa'.2 The Sanskrit word mar;u!ala, meaning 'the circle' literally, is the combination of two words

'ma~4a ' .. (Tib.: dkyil) and 'la'(Tib.: kor), respectively denoting 'the chief divinity and the emanation'; or nirvii~a and salflSiira.3 Thus, we notice that the term itself contains the two counterparts of the formless Ultimate and multiple forms. The ritual of sand-

ma~4ala explicitly demonstrates that the multiplicity of colourful forms return to the stat~ of sunya in the final dissolution of the ma~4ala. One may raise a question: How is the sunya represented in the colourful forms of ma~4alas which are not meant to be

dissolve~? The first question which is often raised in regard to Buddhist ma~4alas is how the bodily figures and primary colours in ma~4alas can be consistent with the prime concept of sunya in Buddhism. There are ma~4alas permanently painted on the walls of ancient monasteries in the Western Himalayas. While facing colourful

ma~4alOf on the wall, we are in a difficult position to understand the non-dualism of forms and the formless affirmed in Buddhism. At first glance, ma~4alas seem contrary to the sunya. I, personally, had been struggling with the fact that Buddhist monasteries are fill~d with images, golden statues and colourful paintings, which, I felt, contradictory to the Buddhist teaching of' sunya'. Nevertheless, one thing was clear: if the ~mpl~yment of colourful forms were contradictory to the quest for the sunya, these

2 cr. Prajiiiipiiramitii Hrdaya-Siltra, trans. MUller 1894: pp. 147-8. 3 Th,e meaning has been explained in the DharmamalJ4aia Siltra of 8th cent. A.D. cf. DMS, trans. Lo Bue 1981.: p. 796.

2

-

forms would not h~ve become the perennial tradition. Thus, colourful forms are present in Buddhist monas,teries as a self-evidence of the non-difference between forms and the

formless. The thesis investigates the question about the colourful forms of ma1)4alas

and their relation to the siinya.

Reflection on the previous Researches on the Ma1J4alas

Tucci draws attention to the cosmic meanings inlaid in ma1)4aias and attempt to relate

those meanings with the human psyche from the perspective of the modern psychology.4

Though ma1)4alas are viewed in correspondence with the deepest level of the human

consciousness, the relationship between their cosmic affiliation and their visual

significance has ~een overlooked in his scope. Many attempts have been made to comprehend ma1)4alas primarily on the basis of ,their association with religious

practices, because they accompany the rituals and spiritual practices. In the field of religious studies, their significance has been read as the representation of doctrinal expositions,S and their ritual process and ritualistic function have been unravel~d.6 In these approaches, the visuals of ma1)4alas have been viewed within the frame of

traditional interpretations, chiefly as symbols with discursive meanings. But they are not

questioned in their sheer visual aspect. The visual aspect of ma1)4alas has been the

focus of art historical studies. In the field of art history, efforts have been made to trace

their formal development. 7 The deities of ma1)4alas have been identified on the basis of

the ancient manuals of the visualization,8 and the empirical ma1)4aias are compared

with possible textual sources.9 The previous researches in art history, while focusing on the visuals, appear excluding their inner contents in its scope. Thus, we notice that most

of the previous studies on ma1)4alas deal with either their religious and cosmic

meanings, or their physical forms. The relation b,etween the meanings and the forms in ma1J4alas has not been a topic of attention.

4 Tucci 1961. 5 Se~ Thunnan & Leidy 1997; Khanna 1979. fj : See Wayman 1992; Brauen 1997; BUhnemann 2003. 7 Se~ Malandra 1993; Leidy, in: Thunnan & Leidy 1997; Luczanits 2005. Ii See Chandra & Vira 1995; Snodgrass 1997: MaIlman 1975. (J See Klimburg-Salter 1999.

3

-

Buddhi~t ma1Jrjaias, though used in religious practices,. are not merely one of the religious paraphen:talia. Yet, they are neither the same as ord~ary works of arts that are free frqIp religious allegories. Being defined to be the object of religious arts, their inner conten~ and visual forms should be perceived all together. In this respect, Jung's

compr~~ension of ma1Jrjaias in the field of psychology is remarkable in unveiling the connec~jon betweep. forms and inner contents of ma1Jrjaias.10 Modem understanding of ma1Jrjalq,s as the mirror of our psyche has to be attributed to Jung's research. His

analysis" of ma1Jrjaias created by his psychotic patients demonstrates the ma1Jrjaias as

symbols constantly recurring in diverse cultures from the ancient to the contemporary. Jung qbserves that ma1Jrjaias appear in the process of individuation in case of his

patients, in order for the self-healing, and he speculates that they spring from an instinctive impulse. He writes that many patients realize the reality of 'the collective

uncons,c,ious' as ~. autonomous entity, and these ma1Jrjaias are governed by the same fundamental laws that are observed in the ma1Jrjaias from different parts of the world.

He use~ words su~h as 'instinctive impulse', 'transconscious disposition' or 'collective unconscious' to express the kernel of ma1Jrjaias as the archetype. Jung views the motif

of mawjaia as 'one of the best examples of the universal operation of an archetype,.ll

Jung's writings on ma1Jrjalas urge us to uncover that the ma1Jrjaias are primarily the

arclietypal space or the primeval space.

Although, Jung's researches on the ma1Jrjaias of psychotic patients unearth the

. fundamental meaning of ma1Jrjaias as the archetypal symbol, his psycho-analytical , . . interpr~tations of their visual symbols have little scope of application in regard to Buddhist ma1Jrjalas, because the cultural background of symbols depicted in particular

ma'.u!a~as have not been considered in his interpretations. The misapplication is exemplified by his interpretation of the burial ground as 'the horror' without the consideration of its tantric context. However, we need to pay attention to his

10 Ju~g 1973. 11 Jubg 1972: p. 69. From the conclusion of his article 'A Study in the Process of Individuation', transl~ted from "Zur Empirie des Individuationsprozesses", Gestaltungen des Unbewussten, (Psychologishe Abhandlungen VII) ZOrich 1950.

4

-

retrospective comments after his research on the malJif,aia symbolism: "Knowledge of

the cOmplon origin of these unconsciously preformed symbols has been totally lost to us. In ord~r to recover it, we have to read old texts and investigate old cultures so as to gain an understanding of the things our patients bring us today in explanation of their

psychic developm~nt.")2 His comment confirms that the research of Buddhist malJif,alas on the basis of the old texts may contribute to illuminate the common origin of the recurring archetype of malJif,aia. In Jung's time, the translations of old texts into the

Western languages had not been done as much as they are today. In the meanwhile, crucial tantras in r~lation to malJif,alas have been translated into English, which I have been tremendously benefited in carrying out my research.

Problem of Forms and the Formless in Buddhist mandalas in the context of the ~ , . .

religious practice

The religious meaning of Buddhist malJrjalas conceived by modern researchers may

be repre.sented by the words of Snellgrove. In his words, two essential concepts of the

malJrjala are implied: the centre and its transformations.

"The malJrjala, the primary function of which is to express the truth of emanation and return (saf!1Sara and nirvalJa) is the centre of the universe ... .Its core is Mt. Meru: it is the palace of the universal moharch, it is the. royal stupa; it is even the fire altar where one makes the sacrifice of oneself.,,)3

His words express the cosmic significance of malJrjalas. However, not all malJrjalas

are charged with cosmic meanings. Devending on the main divinity represented ill the

centr~, the purpose and the meaning of malJrjalas vary. For example, the malJif,ala of the Eight Nagas is for pacifying the venom of the snakes,)4 thus, the cosmic symbolism is hardly appropriate in this malJrjala. Buddhaguhya, in the commentary of the

12 Jung 1972: p. 100. The quotation is from the conclusion of the article 'Concerning Mandala Symbqlism', first published, as "Ober Mandalasymbolik", in Gestaltungen des Unbewussten (Psych'ologische Abhandlungen, VII), ZUrich, 1950. 1:3 Sneillgrove & Skorupski 1977, vol. I: p. 32, n.4. 14 Cf.SDPT, introductory ,commentary by Buddhaguhya, trans. Skorupski 1983: p. xxvii.

5

-

Sarvadurgatiparisodhana Tantra, remarks that each ma1Jrjala is designed for different

PUrpoS~S.lS Thus, we should be clear in the mind that the cosmic symbolism with the emphasis on the centre and its transformation is apt only when we deal with the m(J1Jrjaias of divinities who represent the Absolute. For instance the ma1Jrjaias of Tabo

and Alchi we are dealing with in the text are centred on Mahavairocana who represents the :Gr~a.t Illumina~ion of Enlightenment and the Absolute Bo.dy of the Dharma. Thus, thes,e ma1Jrjalas are charged with cosmic significance, involving such concepts as the

dharmadhlitu (Ultimate Dharma), the silnya (Void) or the bodhicitta (Awareness of 1 "~

Enlightenment).

L~t us look at how the forms and the formless Ultimate are conceived by the religious practitioners. For monks who practice with ma1Jrjala images, the external

". I

ma1Jrjaias are not real ma1Jrjalas. They are merely reflective images (pratibimba). The

real ma1Jrjaia, which is the 'Essence', 16 has to be internally explored. During the

intervi~w I carrie~ out in Ladakh in July 2007 in order to survey what actually irza1Jr!ala,s mean for the present Buddhist practitioners, Geshe Tsewang,17 a practitioner

of H~ruka ma1Jrjala, said:

"When the external ma1Jrjala is successfully internalized, the way how to practice ma1Jrjaia is revealed.,,18

His statement confirms that the complicated external forms are not all about the ma1J4,!la and there is the deeper dimension to be explored. Unless the real ma1J4aia is

tasted, one would not know what the ma1J4ala is, merely by looking at it. Geshe

Tsewang actually ~sed the expression of 'tasting a ma1Jrjala' indicating the inner sensual experience of a, ma1Jrjala. It is remarkable that a religious practitioner used a

terminology of Indian aesthetics in explaining his spiritual experience, having been unaware of what history the concept of 'tasting (rasa)' has gone through in Indian

15 Ibid. 16 The '!IaT}r/ala is called in Tibetan, 'dKyilkor' (the center and the circle), and also 'siiinpo' which means the essettce. 17 Geshe Tsewang Dorje is the director ofNgari Institute of Buddhist Dialenctices, in Leh in Ladakh. III Personal interview, in Leh, Ladakh, on 30th July, 2007.

6

-

aesthetios. The use of the m~taphor, 'tasting a malJq,a/a' by a religious practitioner is particularly significant in the present approach to Buddhist malJq,a/as.

MalJcJa!qs are used in the practice of visualization. However, not all the Buddhists are

eligibl~ to practice the visualization of malJq,a/as. One should be first of all initiated. According to the spiritual ability, the practitioners are assigned with particular malJq,a/as

that are categorized into four groups. These four cat~gories of malJq,a/as correspond to the fo~ categories of tantras: Kriya, Carya, Yoga and Anuttarayoga. Because the Anuttat:qyoga Tantras are the predominant stream of Tibetan Buddhism today, mainly the divinities of Anuttarayoga Tantras are taken up for the malJcJa/a practices. Thus,

only the spiritually advanced monks are said to be able to carry out the malJq,a/a

practice.

MalJeJa/as are understood as the form of siinyata, its reflective image (pratibimba):

the ess~nce of malJcJalas is the siinya, and their forms are the reflective images of the siinya. Realizing the siinya of the self should precede the visualization of the malJq,aia.

FroIl} siinya of the self, the deity is generated as the self. In visualization, a self becomes a divinity through the siinya and returns to the self through the siinya; the deity of the malJc!a~a appears in the siinya and disappears into the siinya. The practice of siinyata, bodhicitta and kariilJa should precede the practice of malJq,aias, and the Buddhist

practice of malJcJalas are meant to strengthen the realization of the Truth, that is siinya. 19

Thus, the Hevajra Tantra, an Anuttarayoga Tantra says,

"The bodhicitta which has both absolute and relative forms should be generated by means of the Mru~l(;lala Circle etc. (malJq,aiacakradi) and by the process of Self-empowerment (sviidhi~!'makramaio."21

19 Geshe Tsewang of Ladakh mentioned emphatically in a personal interview (4. Aug. 2007) that the ma~4alh}practice should be based on silnya, bodhicitta and karil~a. 20 The ~ommentary, Yogaratnamiilii interpretes the term sviidhi~!iinakrama as the emanation of the Process\ofPerfection. cr. Farrow & Menon 1992: p. 215. . 21 HT n. 4. 35, tans. Farrow & Menon 1992: p. 215. The bodhicitta has been translated by Farrow & Menon j'nto 'Enlightened Consciousness', which I fmd inappropriate. I use the original term 'bodhicitta' un-translated.

7

-

The tfmtra succinctly explains about the essence of the ma~rjala. It te!l,ches th~t the maIJrjala is the essence having the nature of void (kha) and purifies the sense faculties,

thus the bodhicitta is cultivated through the malJrjala.22 MalJrjalas are said to be the

abode (pura1!l) of the essence of all the Buddhas (sarvabuddhlitmakam i 3 and bears the great bliss (mahat sukham).24 It is clearly noticed in the tantra that malJrjalas are

defi~ed to be the Essence (slira1!l), or the bodhicitta.2s At the same time they are the me~s to realize the Essence or the bodhicatta. Thus, we observe that in the religious practic~ ,the notions of the sunya or bodhicitta are symbolically implied in the visual images of Buddhist malJrjalas.

Buddhist MalJ4aias as Works of Arts

MQlJ4alas are regarded in the present thesis as works of arts, while their distinction

from ordinary works of arts is also observed. One may question whether we can deal

with malJrjalas under the category of arts in spite that they are meant to serve the

purpose in religious rituals. The question may be, at the first hand, argued back on the basis. th~t the separation between the religion and arts is a modem invention, which

acco~l?~ied the rise of individualism and the emancipation of arts in the West free from the power of the Christian chur~hes. The isolation of arts from religion in the modern concept of arts should be discerned as the freedom from the religious authority, not the denial of religion as a source of artistic inspiration. Even today, the validity of religion as the source of artistic activities remains intact. Secondly, we should notice that malJrjalas are created by artists or monk-artists, yet not by ordinary monks. Above

all, it is revealing that the malJrjalas have been permanently depicted on the walls in the

monasteries in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Especially when they are painted permanently on the wall, they should be considered in their visual dimensions because they are meant to be the focus to be looked at by ordinary devotees. Thus, they are placed in a

22 cr. HT. II. 3. 27. "The Circle (calera) is an assembly (nivaha1{l) and having the nature or the Space element \ (khadhatu), it is that which purifies (viSodhanam) the sense objects (vi~ayii) and other aggregates." Trans. Farrow & Menon 1992: p. 191. 2;j I

cr. HT 11.3.25. Trans. Farrow & Menon 1992: p. 190. 24 ~

cr. HT 11.3.26. Trans. Farrow & Menon 1992: p. 190. 25 cr. IQid.

8

-

different context from that of the initiation maTJf/.alas of tantric rituals. The initiation

maTJf/.alas are created temporarily to be the base of the internal visualization, which are

to be d,ismantled after the rituals are over. One generalizes on the basis of the

information about the initiation maTJf/.alas that maTJ4alas are secret and esoteric. On the

contrary to this &eneralization, the maTJf/.alas permanently painted on the walls of

mo~asteries are o~n and publicly exposed to be seen. Thus, our understanding of maTJf/.alas, at least in case of those permanently represented on the walls, can be dealt

with as works of arts, not restricted by their religious context.

Aesthetic Approach to Buddhist Ma1Jt/alas

In order to examine the relationship between the inner meanings and the visual forms of Buddhist maTJf/.alas, the thesis takes up their aesthetic dimension for the

exploration. For the aesthetic approach keeps us in the track of seeing both the inner contents and the external form in its scope. While I deal wi~ the aesthetic dimension of Buddhist maTJf/.alas in the thesis, they are essentially viewed in their aspect of being an

archetype beyond their association with religious practice. Their being the archetype is dete~inant for our aesthetic appreciation of maTJf/.alas beyond cultural, spatial or temporal boundaries.

I behold especially the fact that maTJf/.alas are appreciated even away from their

religious meanings. The fact should be emphasized that maTJf/.alas can be aesthetically,

or eve~ spiritually appealing without getting their contents and meanings known. This fact sPleaks itself about the importance of visuals of maTJf/.alas. Today artistically

executed maTJf/.ala~ are publicly displayed in exhibitions, and people appreciate them even without knowing their ritualistic context or symbolic indications. People are overwhelmed by the exquisite forms and bright colours. However, the appreciation of ma1Jf/.alas is different from that of ordinary pictures of portrait, still life or landscape,

etc., in ~at the exquisite forms of ma1Jf/.alas lead one to feel something transcendental or aweSpme. One may have such experiences even without worshipping divinities

delineated in the maTJf/.aias. These experiences would be better described in terms of the

9

-

reactiop of the heart, which we may call 'aesthetic rapture'. Such experiences

unambiguously indicate the inner meanings different from religious associations or discursiye interpretations of symbols. The non-discursive meaning inbuilt in tlJ,e visuals

of maTJ4aias is proved by the present use of maT}r!aias as a psychotherapeutic met40d in

the We,st. In this method, no meanings are instructed to patient~. Patients are to copy the maT}r!aias given to them, which is quite opposite to Jung's method encouraging the

active jrp.agination of patients. And in primary schools, children are given with drawing of maT}r!alas and asked to fill the drawing with the colours they like. Though the

, . contemporary applications of maT}r!alas in the West are doubtful in the matter of

whether such regulated imitations could bring the desirable result, they mirror the idea that th~ heart spontaneously responds to the visuals of maT}r!alas and they influence in molding the structure of the mind, whether consciously or unconsciously. The main question of the thesis is, thus, phrased as such: 'How do the visuals of Buddhist maT}tjalas appeal to the heart of people even away from their religio-symbolic

meanings?'

Scope of Empiri,cal Research: Ma1Jt/aias of Tabo and Alchi in the Western Himalayas from the 11th cent. A.D.

M.afJr!alas have been the perennial theme in the religious arts of India. Its symbolic

meaning~ are intensified through elaborated artistic language. especially within Hindu and Buddhist traditions. The forms of Buddhist maT}r!alas are traditionally laid down, on

the b~is of the vision attained at the state of the absorption into the non-conceptual world. The Buddhist maT}r!alas, in general, may be described in their geometric palace

with clear indications of the four cardinal directions. The divinities, either represented in anthr0nomorphic fQrms or in symbolic forms, are arrayed in the hierarchical order around the centre within the geometric palace. Here, Budd4as and bodhisattvas are conceived as spatial manifestations from the centre. However, as we will see in the main

, ,

text, th1 maT}r!alas of Tabo 40 not conform to our general image of Buddhist maT}r!alas.

They ~e neither based on the geometric structure, nor are their centers conspicuous. The visual forms ()f maT}r!alas vary. Thus, it is necessary to narrow down the scope of

10

-

the empirical examinations to particular examples.

The present thesis focuses on the ma1;u!aias in the monasteries of Tabo and Alchi in

the Western Himalayas, in order to approach the question of the r~lationship between the inn~r conte~ts and the visual forms, more particularly about how the Buddhist marj,r:ja!as appeal to the heart of people. even away from their religio-symbolic meanings.

The~e examples have been chosen because they display rare refineP1~nt and soph~s~ication in their forms as comparable with the classical arts and also because they are on~ of the earliest ma1J4aias extant in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. Ma1J.r:jaias are not isolated paintings in Tabo and Alchi, but central in the whole iconographic program and vital in creating the visual effect of the space.

The monasteri,es of Tabo and Alchi belong to the period of the Second Diffusion of Buddhism (phyi dar) in the Tibetan history that was carried out by the patronage of Puran-Guge in the Western Himalayas.26 As is also observed in other monasteries

establish~d under the same historical background, such as Nako, Duildkar, Sumda and Mangyu, Mahavairocana is the central theme of the iconographic program of the

monast.eries at this time. Cons~quently we encounter in these monas~eries the ma1J.r:jaias ':.

related to Mahavairocana. His .position as the central divinity characterizes the Yoga

Tantra ,class, thus these ma1J.r:jaias with the image of Mahavairocana at the centra are

justifiably viewed in association with what the Yoga Tantras say.

The ma1J.r:jaias of the dukhang in Tabo are well preserved. So far as the present

remain~ indicate, t4ere were only two ma1J.r:jaias represented in the dukhang in Tabo: the Vajradhatu-maQc;lala and Dharmadhatu-Vagisvara-MaQc;lala. The Vajradhatu-maQc;lala of Tabo made up of thirty-three clay sculptures is one of rare sculptural ma1J.r:jaias set in the

architectural space. Although the bibliography of Rin-chen-bzang-po (958-1055 A.D.) tells us :that he founded the monastery of Tabo, the inscriptions reveal that the monaster was founded by Yeshe 6, ca. 996 A.D .. The research on the inscription in the dukhang also reveals that the wall paintings as well as the sculptural ma1J.r:jaia of Tabo

26 Apart from Tabo and Alchi, these monasteries were established at this time.

11

-

may be assigned to ca. 1042 during the renovation of Jang Chup 0.27 The o,ldest structure of Alchi monastery, that is, the dukhimg is almost contemporary

to the d1:lkhang of Tabo, founded in the mid-II th cen~y by Kelden Sherap, a follower of Wn-

-

divinity. Though there is a fundamental difference between the aesthetic seeing and the

visualiZ'!-tion in re~ard to the way the visuals are processed, the visualization practice of mar;4a1as, systematically laid out by the tradition, demonstrates convincingly the innate

depth of marJ4alas, which could be related to the aesthetic immersion to them. For the

maJqr 9l;1estion of the present research, the religious practice of visualization also gives invaluable references to 'the sounds' that make up for the g&P between the ultimate state

I \ '.

in the nature of sunya and the manifested images of pratibimba.

The descriptions of visualization indicate that the levels in between the sunya and

mUltiple forms in ma7}rjalas are conceived in the nature of sounds, which is consistent

with the. fact that the practice of mantras has been the essential soteriological means in

realizing the formless Ultimate in the Yoga Tantras. The concept of subtle sound plays the central part in the tantric practices and holds a crucial key to interpret the tantric methods of salvation. The visuals of Buddhist ma7}rjalas have been elaborated in

association with the mantrayana practice, and they are always combined with mantras and muc{ras in tantric practices. Thus, the thesis looks into th~ notion of subtle sound that e~plains the qonceptual basis of the mantra practice. Specifically ~ts philosophy

formul~t~d in 'the doctrine of vak' may be taken as the guideline in approaching the questiohs of forms and the formless in ma7}rjalas.

The sound in spiritual traditions of India has been taken as the crucial factor in the descriptions of the cosmic revelation and the world manifes~ations. The term vak is traced b~ck as early as the IJgveda. Vak has been speculated as the principle of the divine m.anifestatiops and the multiple creations in the world. Sophisticated philosophy of vak is found in the Trika Saivism of Kashmir. The doctrine of viik in the Trika Saivism is an achievement brought about by the synthesis of diverse streams of spiritual tradition~: earlier Saiva tantras, Bhartrhari's philosophy of sound (sabda-brahman), the

VijfUinav~din's p~losophy of logic, and the non-dualistic vision represented in its pratyabhijna (rec()gnition) philosophy. The comprehensive philosophy of vqk in the Trika S~ivism demonstrates a systematic way to explain the non-dualism between all the phenomenal objects and the Supreme Divine, that is, Siva. It renders elaborate

13

-

expositions about the nature of worldly manifestations and their relation to the Ultimate

Orig~n. Thus, I take the texts qf Trika Saivism as the main source of understanding vlik. Since the doctrine of vlik mainly deals with the question regarding the relationship between the Un-t;nanifest Source and multiple creations, it is expected that the

co~prehension of vlik would impart the framework through which we can explain what mak~s $e visuals of Buddhist maTJtjalas appeal to the heart o~ people even away from thei~ dctrinal asso,ciated meanings. Moreover, its wide scope that ellcompasses the field of at(sthetics has been testified by the poetics of dhvani in the texts of Dhvanyliloka and its Locana.

The non-dualistic philosophy of the Trika Saivism is pronounced in profound stanzas in the Siva Siltra by Vasugupta. The logical argum~nts of its non-dualistic theology has been carried out by the Pratyabhijiia School, represented by Somananda (c. 900-950) and his disciple, Utpaladeva (c. 925-975). Abhinavagupta (c. 975-1025), who represents the culminating point of the Indian aesthetics with his theory of rasa and dhvani, is the descendent of these philosophers of th~ Kashmir, and he is the one who accoml?lished and synthesized the different streams of tantric traditions on the basis of the non-dualistic philosophy established by the Pratyabhijiia School. These key

I

personages of the Trika Saivism in Kashmir are contemporary to the period when the , . region qf Western Himalayas was in active interacti(;ms with Kashmir in terms of not only economy but also arts and religion. 29 Especially, Abhinavagupta is exactly , . contemporary to Rin-chen-bzang-po (958-1055) who translated a number of texts into Tibetan and motivated the foundation of monasteries along the Western Himalayas,

2fJ The presence of Kashmir artists in Western Tibet has been discussed at length by Tucci in his Transhima/aya (1973). He mentions about the artistic influence of Kashmir on Western Himalaya (1973). He refers to the importance of Mangnang and its paintings being done by a number of painters from Kashmir summoned by Rin-chen- bzang-po (pp. 91-93). He exemplifies it with illustrations ofa figure of a siidhu (PI. 114) in affinity to the one depicted on terracottas from Harvan in Kashmir, figures of divinities (BI. 122) and an ivory statue from western Tibet (PI. 12~. "Work such as this provides indisputable \evidence of Kashmir influence in Tibet in the lOth and 11 centuries and similar examples from a later period have been found at Alchi in Ladakh." (p. 92) He adds examples from Tsaparang (PI. 138), Thol1ng (PI. 136) and Tabo (PI. 129) as revealing their Kashmir origin. Snellgove a~so states .about the same point (1977: p. 16): "It may be taken for granted, and we think

quite rightly, Ithat the main source of artistic work in Western Tibet and Ladakh from the lOth to the 13 tb centuries was:; north-west India, and especially Kashmir, which was then still a Hind-Buddhist land, and which is often. specifically mentioned in Tibetan sources."

14

-

including those ofTabo and Alchi.

The Trika Sa,ivism, in its philosophical exegesis, makes up for the non-dualism

between the UltiIllate and the phenomena conceived by the Yogacara Buddhists. Especially, the conviction of the Pratyabhijiia School that Siva permeates everything and the 'recognition' (pratyabhijiia) of one's own identity (atman) as Siva leads one to the salyation reminds us of the Yogacann's exposition of Tathagatagarbha. Tucci has

recognized the validity of the Trika Saivism of Kashmir in understanding mQl)ijalas. In

his book on maT}4alas, he expressed his view that the Hindu yantras are "the

quintessential red~ction of the identical idea which the Buddhist maT}4alas are based on".30 Consequently, he draws upon the Hindu tantras even in interpreting the symbolic

meanings of the Buddhist maT}4alas. He interprets the five Buddha Families in parallel

with the five aspects of ParamaSiva or the five tattvas in the absolute plane: Sivatattva, Saktitattva, Sadasivatattva, Isvaratattva, Sadvidya. And the five aspects of Sakti are also referred in relation to the five Buddha Families.31 Most of all he pays attention to the concept of sound in understanding of maT}4aias, and he introduces the third chapter of

Abhinavagupta's Tantrasara to explain the symbolism of sound which lays the basis for the relation between the mantra and the emanation of images.32 Tucci's attention to the

texts of Trika Saivism encourages us to look up their philosophy in exploring the Buddhist maT}4alas. The vast cosmic vision of the Trika Saivism certainly renders

parallel concepts that can be compared or applied to those of the Buddhist maT}4alas, as ,

Tucci displays. The relationship between Kashimir Saivism and Tibetan Buddhism has drawn attention of eminent scholars, and has been explored in terms of the historr3, the religious practice,34 and arts. The cultural connection between Kashmir and the Western

Himalayas during the 10th to 13 th cent. A.D.35 is particularly relevant in regard to the empirical research of the Buddhist maT}4alas of Tabo and Alchi. The fact that the artists

30 Tucci 1961: p. 47. 31 Ibid.: pp.':50, 55-7. 32 Tucci 196) : pp. 61-3. :33 , See Klimgurg 1982. \ 34 See the artiCles Buhnemann 199~; Ruegg 2001; Sanderson 1994, 200 I. :l5 See Pal 1989.

15

-

had be~p brought from Kashmir to embellish these monasteri~s36 and their arts reflect the style of KashiIpir arts in these monasteries37 should not be ignored. However, it is

not the intention of the thesis that Buddhist ma1J4alas are interpr~ted in tenns of the philosqphy of the Trika Saivism at the level of symbolic or doctrinal meanings. The appFca;tjon of the philosophy of the Trika Saivism to the symbolic meanings of Buddhist ma1JtJalas is avoided, because the doctrinal or symbolic meanings have been

consciqusly endowed in the context of particular religious practices, thus they should be interpreted within the context. It should be clarified that the doctrine of vak is looked up in the thesis for the purpose of interpreting the aesthetic phenomena and structuring the

different levels of meanings and manifestations of ma1J4q./as from the aesthetic

perspective. Vale, primarily viewed as the principle or vehicle of transfonnation, is scrutinized in the thesis in its four aspects: paravak, pasyantf, madhyama and vaikharf.

Th,e doctrine of vak has its validity also in regard to the common origin of

ma1J4alas that Jung questions about. Let us briefly think of what is meant by 'the origin'.

From the religious perspective, the origin would be the Essence of the divinity, which is

36 The presence of Kashmir artists in Western Tibet is especially well com>borated by Rin-chen-bzang-po's biogr~phy where the name of a KaShmir artist is mentioned. Bhidhaka, and thirty-two are said to be brought b)i: him, as was requested by the King Yeshe O. 37 Pal, while illustrating stylistic variations and their chronological order .of mural paintings of Alchi, states that ','the style of the murals in the Dukhang and the Sumtsek is generally considered to derive from Kashmir wpich was undoubtedly the principal source for Western Tibetan artistic tradition at that time" (1982: p. 1':9). He presents paintings of Western Tibet rendered in Dukhang and Sumtsek as "the only surviving evidence for inferring what Kashmir paintings OIice looked like" (ibid), because no comparative paintings have survived from Kashmir. Luczanits states, "all the original paintings of Alchi and related monuments ',can be considered to have been made under the supervision of Kashmiri craftsmen, or at least the strong influence ofa Kashmir school." (1997: pp. 201-2)

In regard to the arts of Tabo, the style of Buddha figures in the west wall of Ambulatory corridor in the Main Temple of Tabo has been comparable with the metal sculptures attributed to lOth to 11 th century Kashmir. One of the closest comparisons would be between the Maitreya Buddha in Tabo (Klimburg-Salter 1997: figs. 181, 182) and the standing Buddha in Cleveland Museum (Klimburg-Salter 1982: PI. 27). Klimburg-Salter suggests two phases of artistic activity in. Tabo main temple: original in 996, and renovation in '1042. The 2nd phase consists of four different stylistic groups. She attributes the Group A (paintings in the Ambulatory and clay sculptures of ma1J.rj.aia in the assembly hall) to the true Kashmir-derived style, and presumes that the Group A and B (all the narrative paintings and the protectress in the Assembly Haip may have been undertaken by the Kashmir artists, as stated in Rin-chen-bzang-po's biography,(Klimburg-Salter 1997: p.Sl). She considers other groups of style derived from the Group A. Luczanitsdiscbrns that the style of thirty-three clay sculptures of the Vajradhiltu-mal}Qala is only partly comparable to \the contemporary Kashmiri style, while the sculptures of Alchi are recognized as the "direct influenc~ ofKashmiri art" (Luczanits 1997: p. 202).

16

-

manif~sted in the rrzalJq.alas. In respect to the visual dimension of malJq.alas, their origin is the artistic inspiration that gives birth to such forms. Probably Jung has not had thought of the arti~tic inspiration when he mention~d the origin of malJq.alas though it is

possib~e he considered the origin in religious terms as well. From the psychological per~pective of Jung, the origin of malJq.alas would mean the spiritual origin that would give bjrth to the inner symbolic meanings. However, these concepts are not to be separatep ultimat~ly. If the meanings and the forms are interrelated, the devotional sourge, the spiritual source, and the artistic source would be also interconnected, or even converge. The quest for the common origin of malJq.alas could bring altogether the

divinity, the deepest consciousness (or collective unconscious in Jungian term), and the artistic inspiration. The doctrine of vak portrays its highest level, paravak, to be the

artistic inspiration (pralibha) as well as the pure consciousness (sarpvid). And at the

same t~~e it is worshiped as 'Devi (the Primeval Goddess)'. Thus, it certainly contains \

the cru~ial'key in explaining the common origin ofmalJq.alas.

Primary Sources of the Research

T~e underst~dings of the doctrine of vak in the thesis haye been chiefly based on texts th~t represent the synthetic phase of the Trika Saivism, such as Abhinavagupta's Tantrliloka with Jayaratha's commentary and his Paratrisikii-VivaralJa. The verses from

the Spandakiirikii with one of its commentaries by Riijanaka Riima called Spandavivrti have been also consulted. For the logical expositions of vak, the invaluable sources are . Utpala

-

relevant verses on vak are painstakingly translated into English by Andre Padoux in his book 'vac: The Concept of the Word In Selected Hindu Tantra' ,40 which immensely benefits my research on vak.

In regard to the Buddhist ma1Jr.jalas, the thesis is based on the texts that belong to

the Yogatantra class, due to the nature of the examples of Tabo and Alchi. Especially, the commentaries of the major Yoga Tantras by Buddhaguhya help us in comprehending cryptic words of tantras. And his own composition on the ma1Jr.jalas presents us with the

discourse on ma1Jr.jalas integrated from different Yoga Tantras. Buddhaguhya lived in

the 8th cent. A.I? Taranatha mentions him as being very well acquainted with Kriya, Carya and Yoga tantras.41 The primary texts on the Buddhist iconography such as the Sadhanamala, VajravalT or Ni~pannayogavali, 42 are consulted only occasionally in order to compare the data from empirical examples with the conventional rules. The major texts consulted in the present research are described below.

* Mahavairocanabhisa1]1bodhi Tantra In the Tibetan tradition, the Mahavairocanabhisa1]1bodhi Tantra is classified as a

Carya Tpntra. Snellgrove mentions that it belongs to the early Yoga Tantras.43 In the summari~ed co~entary of the same Tantra, called the Pi1Jr.jartha, Buddhaguhya mentions only two classes of tantras, Kriya and Yoga, which implies that the four divisions of tantras are a later denomination. Buddhaguhya classifies the

Mahavairocanabhisa1]1bodhi Tantra in the category of ubhaya (dual), which combines

Pandey 1954. 40 Padoux 1992. 41 Cf. Skorupski. 1983: p. xxv, in the introduction to his translation ofSDPT. 42 "The Ni~pannayoglivai'i (NSP) and Vajrliva/'i (VV), two complementary works by Abhayakaragupta (1064-1125) were written around 1100 A.D .. Both texts describe in great detail twenty-six mal}Qalas from various Tantric traditions. NSP focuses on three-dimensional forms of these ma1Jtjaias for visualization

(bhiivyama1Jtj~la) and describes in detail the iconography of deities. VV explains the construction and ritual use of two-dimensional ma1Jtjaias, which are to be drawn (le/chyama1Jtjaia) on the ground." (Btlhnemann 2905: p. 5643). "According to Abhayakaragupta, the Vajrliva/'i, a practical guide to all the preliminary rit~s preceding the initiation into the mal}Qala, is the main text while the Ni~pannayoglival'i, which deals witp ma1Jtjalas in details, and the Jyotirmaiijar'i, which deals with the homa ritual exclusively, are supplementary." (Btlhnemann & Tachikawa 1991: p. xvi). 43 Cf. Snellgrove 1987: p. 196.

18

-

the orientations of both Kriyii and Yoga Tantras.44 While the, text provides us with a

profound philosophy of Mahavairocana and fundamental concepts of the mantrayiina, we encounter invaluable ma~rials that especially help in comprehending ma1J4alas of Mahava!rocana. The Tibetan text with Buddhaguhya's commentary has been translated

by Stephan Hodge.45 His translation entails the Pi1J4iirtha as well.

* Sarvatathiigatatattvasa""graha The text of Sarvatathiigatatattvasa""graha gives more direct references to the

Vajr~dh~tu-m~

-

Danapal,a's Chinese translation". 49 Thus, Giebel's' translation of the text of

Amoghavajra can be used for examining the Indo-Tibetan ma1J:tjalas of Tabo and Alchi. I have b,een benefited a great deal from Giebel's English translations as well as from those by Snellgrove.

Sa,rvqdurgatipariSodhana Tantra

The first translation of this Tantra from Sanskrit into Tib~~an was made sometime at the end of the eighth century A.D. and revised sometime before 863 A.D.sO Some informat,ion is available from Taranatha and Blue Annals, which refer to three Indian

co~entators: Buddhaguhya, Ananpagarbha (early 9th cent. A.D.) and his teacher VajraYarmanSI. E.in-chen-bzang-po (958-1055 A.D.) translated two works of this Tantra.

skdrupski's English translation' of the Tantra is b~ed on t4e Tibetan version which was tr~.slated from Sanskrit sometime during the first half of the 13th cent. A.D. by Lo tsa ba Chog, Chos rje dpaZ. Chapter II of the Tantra is especially useful for the study of Buddhist iconography and mal}tjalas. However, the descriptiQns of the divinities are confined to their mudrlis and locations, and colours, which are simple and unelaborated. Vajravarman's commentary gives detailed accounts on the basic mal}tjala of the TantraS2

and the divinities of mandalas. 1

* Dhamiamandala Sutra ., , Its original Sanskrit text has been lost. Its authorship is attributed to Padmakara by

Tucchi, l,lowever, Lo Bue clarifies that it is attributed to BuddhaguhyaS3 on the basis of the Tan/lfr (the ~econd part of the Tibetan canon). It is a philosophical poem of 386 verses. ~uddhaguhya states that he explains the mal}tjala's divinities and their palace from the substance of all the great tantras. The text is divided into eight sections:

49 Cf. STTS, trans. Giebel 2001: p. 7.(translator's introduction). 50 Skorupski 1983: p. xxiv, in the translator's introduction to the SOPT. 0;1 " :t_ ' From a short colophon at the end of a work by lUlandagarbha -who was a renowned scholar of the yoga tantras- vir learnt that Vajravarman came from Siilhala (Sri Lanka) and was Anandagarbha's teacher." ESkotupski1983: p. xxv). 0;2 \ . SOPT, trans; Skorupski 1983: pp. 311-312. 53 Buddhaguhya was contemporary to the Tibetan King Khri-srong-Ide-brtsan who ruled from 754 to c. 798. He is also t;ontemporary to Padmasambhava and Santar~ita. Cf. Lo Bue 1987: p. 788.

20

-

substance; categories; literal definition (vv.51-4); structure (vv.55-177); faults; virtue; example' and symbolism (vv.202-386). It lists and describes in ,great detail the essential constituents of the conventionalized fivefold scheme of mal;u!aia. Lo Bue states that it

gives the earliest known account of the conventionalized ma1J4aia as we know today.54

* Nam~sa1[lgfti The Namasa'Tlgfti reflects the popularity of devotional practice in the 8th cent. It

was.still popular in north-east India in the early 11 th cent. The text was translated into , Tibe~an during the first period of translation. 55 A commentary to the Namasa1[lgfti that has been affiliated to the Miiyajaia Tantra has laid the ritual of the ma1)q.aia of

Dharmadhatu-Vagisvara, which is one of the main ma1)q.aias in Tabo and Alchi. The

text has been understood as the devotional hymns for MafijusrI, and the title has been transhitep into 'Litany names of MafijusrI' . In contrast to the pr~valent understanding of the text, Chandra draws a new understanding of the text, on the basis of the titles of Chinese, Tibetan, and Sanskrit manuscripts. 56 He argues that the Namasa1[lgfti refers to

litany names of Advaya Paramartha (Mahavairocana in the context of the Yoga Tantra) recited by MafijuSrI.57 The text is a crucial source which tells the miture of the Ultimate, as it had been understood in the period when the ma1)q.aias of Tabo and Alchi were

established.

Overview

Part I of the thesis surveys the external forms and the symbolic meanings of

Buddhist ma1)q.alas. The physical dimensions of empirical examples are described with

special reference to those in Tabo and Alchi, and the relevant textual accounts are briefly looked upon. The symbolic meanings of the divinities are comprehended one the basis of the root tantra of the Yoga Tantras. From the symbolic dimension of ma1)q.alas

in association with the Buddhist tripartite, the discussion of various levels of forms is

54 cr. DMS, in the translator's introduction, Lo Bue 1987: p. 790. 55 cr. Davidson 1981, his introduction in the translation of the text NS. Also see Klimburg-Salter 1999: p. 317. Ii Gt; cr. Chandra 1993. H -1 b 3D2 57 cr. Ibid. pp. 391-4.

21

- conduce

-

Part I

P'1rceptible Forms and Symbol~c Meanings of Buddhist Mandalas . .

-

Part I Perceptible Forms and Symbolic Meanings of Buddhist MaIJ4aias

1. Examining Buddhist MalJQaias of Tabo and Alchi f?n the basis of Graphic and Textual sources

1.1. Vajradhatu-maQ

-

1.3.3.3.Distinct Features of the three ma1J4alas in the third story 59 1.3.4. Discourses from the Inscriptions: the ideal of siinya

and the triguhya of kiiya-viik-citta 60

1.4. Relationship between textual sources and graphic ma1)r;ic:1as 61 1.4 .1. Discussions in regard to the ma1)r;ialas of Tabo 61 1.4.2. Reflections on the relation between the texts and the graphic ma1)r;iala 64

2. Symbolism

2.1. What we learn from the doctrinal expositions of ma1Jr;ialas

2.2. Entrance to the ma1Jr;iala ground

2.3. Divinities of the ma1Jr;ialas of Yogatantras 2.3.1. Mahavairocana and Four Buddhas

66

66

67

69 69

2'.3.2. Five Buddhas: five kulas as five channels of emanation and absorption 73 2.3.3. Sixteen Bodhisattvas 75 2.3.4. Ma1)r;iala deities originating from Sarvatathiigata 79

2.4. Symbolic association of ma1)r;ialas with the Buddhist notions of trikiiya and triguhya 80 2..4.1. Three-divisional space and Buddhist concepts of tripartite 80 2.4.2. Ma1)r;ialas in correspondence to trikiiya and triguhya 81

3. Levels of Forms implied in the Discourses on Ma1)i/aias 84

3.1. What characterizes the form of ma1)r;ialas? 84

3.2. Dimensions of colours in ma1)r;ialas 85 3.2.1. Colours viewed as projection of consciousness in Buddhism 86 3.2.2. Intrinsic sensuousness of the colours and reflection of dharmadhiitu 86 3.2.3. Colours and mantras 87 3.2.4. Symbolic layers of colours 88

3.3. Levels of Forms as revealed in the discourses of Buddhaguhya 90 3.3.1. Three levels of ma1)r;ialas: svabhiiva, samiidhi and pratibimba 90 3.3.2 .. Fourfold shape of the ma1)r;iala palace 93

24

-

3-.3.3. Levels of forms experienced in ma1JcJalas 3.3.4. Subtle levels externalized in ma1JcJalas:

94

ma1JcJalas of kaya, vak and citta 94

4. Practice of Visualization 97

4.1. Rescription of Visualization 97 4.1.1. Description given by contemporary practitioners 97 4.1.2. Description given in the Sarvadurgatiparisodhana Tantra 98 4.1.3. Description given by Buddhaguhya 100 4.1.4. Description by MaftjusrImitra in his Upadda on the Namasarpgfti 101

4.2. Concepts extracted from the visualization 102 4.2.1. Association of the bodily form of a deity with the syllable 102

4.2.1.1. Vowels and consonants: bodhicitta and bfja 102 4.2.1.2. Prominance of the syllable A 103

4.2.2. Ma1JcJalas, mantras and mudras as a compound 104 4.2.2.1. Association of ma1JcJalas with mantras 104 4.2.2.2. Association of ma1JcJalas with mudras 105

5. Non-'~ualism of Forms and the Formless in the Practice and Theory of Ma1Jifaias 107

5.1. Non-dualism of forms and sunya 107 5.1.1. Sunya and ma1JcJalas 107 5.1.2. Non-dualism of sunya and rupa 109 5.1.3. Using forms in the expression of what is formless 110

5.2. Transformation of sunya into perceptual ma1JcJalas 111

6. Summary and Questions 112

25

-

[Ill. 1] Ground plan of the monastic complex

-

Front view

Back view

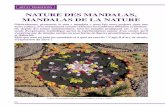

1. Sumtseg as a three-story stiJpa, Alchi

-

Part I.

Perceptible Forms and Symbolic Meanings of Buddhist

Ma1J4aias

1. Examining Buddhist Ma1Jl/aias of Tabo and Alchi on the basis of Graphic and Textual sources

The main temple 'dukhang' of Tabo (founded in 996. A. D.) consists of five parts: the entry hall, the assembly hall, the circumambulatory path and the sanctuary. (Ill. 1) For the present research, I look up only two mal)q.a/as in the assembly hall, although the

dukhang of Tabo is resplendent with valuable materials that require careful attention

from different disciplines of study. Some traces of orderly compositions that resemble

mal)q.a/as are excluded in the examination because of their unintelligible portions of the

composition. So we have a Vajradhatu-inaQ

-

conventional imagination of a ma1)tjaia in geometric composition. Many of them are

compositionally identical only with slight variations in the matter of colours and gender

of divinities depicted in them. I confine the scope of the examination to the ma1)tjaias of

dukhang and sumtseg, assigned respectively to 11th and early 13th century A.D. As is the case with dukhang of Tabo, ma1)tjaias of Alchi are related to the Vajradhatu-maI:lC;lala and Dharmadhatu-Vagrsvara-M~9ala. As far as the scholars have discovered, there are also ma1)tjaias in the DurgatipariSodhana tradition? Here the central divinity of the

ma1)tjaias is associated with Mahavairocana or Sarvavid-Vairocana. Apart from

Mahavairocana, Sakyamuni, MatljusrI and Prajfiaparamita frequently feature in these structures. Seven large ma1)tjaias are painted on the walls of the dukhang: two on each

of the sidewalls and two on the entrance wall, each of which is of over three metres in

diameter. Over the doorway is a small ma1)tjaia of Ak~obhya.

The three-story structure, sumtseg is located beside the dukhang. It accommodates

ten ma1)4aias on the second story and three on the third story. The sumtseg is an

architectural stilpa, which is traditionally adored as a form of the dharmakiiya. (PI. 1) And the inscription in the sumtseg reveals that it is the visualization of Buddhist teachings.3 A three-dimensional stilpa is placed at the center of the sumtseg. The design of the stilpa within another stilpa is also observed in the small twin-stilpa in front of the

sumtseg .... It should be noticed that the ma1)tjaias of the sumtseg are painted within the

stilpa, essentially participating in the expression of the dharmadhlitu.

1.1. Vajradhatu-mal)cJala

1.1.1. Tabo

1.1.1.1. Description

In the Assembly hall of the dukhang, the thirty-three clay sculptres are the predominant visuals. (PI. 2) The central statue of Mahavairocana (h. 110 cm) at the back

2 Ma~9ala No.3 and No.6 in the dukhang; See Snellgrove & Skorupski 1977: pp. 39-40. :J For the original Tibetan inscriptions and their English translation, see Snellgrove & Skorupski 1977: p.

48.

28

- 2. Vajradhatu-mal).

- 4. Ak~obhya of the Vajradhiitu-maI).

-

of the hall is four-bodied, placed on a throne that is formed by a s~ries of rectangular and ciz:qular platforms topped by a double lotus. (PI. 3) The frontal body of the central statue is now painted in gold on their faces and in silver on the bodies and the hands, yet the trac~s of the w,hite colour are not difficult to be noticed below the gold and silver layer. And three other bodies are clearly informative in revealing the original colour of

, '. .,

thd central statue in white. The four bodies of the central statue, divided by wooden , frames pf the back of the throne, are directed to the four quarters, and seated in the vajraparyankiisana with their hands in the form of dharmacakrapravartanamudrii. The

statue of Mahavairocana is positioned slightly higher than the level of the statues of the four Buddhas (h. 105 em) which are placed on the south and the north walls.

Thirty-two cl~y sculptures4 are positioned along the fqur walls. They are bound to the middle of the walls as if they are floating in the ethereal space. Except the four figures flanking the doors of the west and the east, each statue is backed by a perfectly round mandorla. The mandorlas are in high relief at the outermost rim with the pattern of flames.

The statues of the Four Kula Buddhas are distinctive; the inner circle of their mandorlas are painted in red; their mandorlas have additional rows of vajra; they are seated in the posture of vajraparyankiisana. They are identified on the basis of the

mudriis, the colours of the bodies and animals painted beneath them. Two statues on the south wall are Ak~obhya (PI. 4) and Ratnasrupbhava. The former is painted in blue and shows the bhumisparsamudrii. The white elephants are painted on both sides of his lotus seat. TJ:l@ latter is painted in golden-yellow. His right hand shows the varadiimudra, and figures of horses could have been painted beneath his lotus seat, yet in a defaced condition, it is difficult to recognize now. Their corresponding statues on the.north wall are Amitabha (PI. 5) and Amoghasiddhi. Amitabha is painted in red and shows the dhyiinamudra. Peacocks are drawn on the side of his lotus seat. Amoghasiddhi is

4 According to Tucci ( 1988 [1935]: p. 65) there were originally 37 figures which is the more usual number for the Vajradhatu-mal,l~ala. His logic is that the many of the stucco figures have been remade and when they were remodeled the original iconographical criteria were not preserved. Especially, four guardian figures are wider because they in part occupy space originally intended for four goddesses. However, the imagination of the four mudras ofSarvavid Vairocana being placed right at the beginning and end ofthe main hall doesn't appear appropriate.

29

-

painted in bluish green. He shows the abhayamudrli.On both sides of his seat are

painted a pair of garufja.

Then the remaining statues, except the four terrific statues at the doorways, have around their bodies the circular mandorla of the white gradually changing to the red or

the red gradually shifting to the white. A pair of statues is placed on both sides of each of the four Buddhas. So, in total, sixteen figures flank four Buddha figures. They show

different mudrlis in the modes as if they hold something. They are also seated on the

lotus seat, not in the vajraparyankiisana, but in sattvaparyankiisana (with only Qne foot visible over a tigh). Their body-colours are white, blue, red and dark-green. The colour scheme of these statues is not definable, though it is evident that a colour is determined depending on the iconographic convention of a deity.

The eight female figures are located in pairs to the side of the guardian figures

along th~ east and west walls. A pair of guardian figures is placed on the east wall, and another pair at the

entrance, '\0 the circumambulatory path. They are in ferocious appearance and their bodies are painted in blue, yellow and red.

These striking stucco images are placed in a level so as to look down to the visitor.

In this Vajradhatu-mru;tQala, the identification of the central image and the four Buddha images i~ not doubtable due to their clear representation of vehicles, mudrlis and body-colours. But the rest of images are possibly identified only when we rely on the textual