The public trust and the First Americans

Transcript of The public trust and the First Americans

title: ThePublicTrustandtheFirstAmericansauthor: Knudson,Ruthann.;Keel,BennieC.

publisher: OregonStateUniversityPressisbn10|asin: 0870710257printisbn13: 9780870710254ebookisbn13: 9780585271309

language: English

subject

IndiansofNorthAmerica--Antiquities--Collectionandpreservation--Congresses,IndiansofNorthAmerica--Antiquities--Lawandlegislation--Congresses,Archaeology--Moralandethicalaspects--UnitedStates--Congresses,Culturalproperty,Protectionof--Un

publicationdate: 1995lcc: E77.9.P621995eb

ddc: 973.1

subject:

IndiansofNorthAmerica--Antiquities--Collectionandpreservation--Congresses,IndiansofNorthAmerica--Antiquities--Lawandlegislation--Congresses,Archaeology--Moralandethicalaspects--UnitedStates--Congresses,Culturalproperty,Protectionof--Un

Pagei

ThePublicTrustandtheFirstAmericans

Pageii

THECENTERFORTHESTUDYOFTHEFIRSTAMERICANSTheCenterfortheStudyoftheFirstAmericansisanaffiliateoftheDepartmentofAnthropologyatOregonStateUniversity,establishedinJuly1981byaseedgrantfromMr.WilliamBingham'sTrustforCharity.ItsgoalsaretoencourageresearchaboutPleistocenepeoplesoftheAmericas,andtomakethisnewknowledgeavailabletoboththescientificcommunityandtheinterestedpublic.Towardthisend,theCenterstaffisdevelopingresearch,publicoutreach,andpublicationsprograms.

TheCenter'sPeoplingoftheAmericaspublicationprogramfocusesontheearliestAmericansandtheirenvironments.TheCenteralsopublishesaquarterlynewspapercalledtheMammothTrumpet,writtenforbothageneralandaprofessionalaudience,aswellasanannualjournal,CurrentResearchinthePleistocene,whichpresentsnote-lengtharticlesaboutcurrentresearchintheinterdisciplinaryfieldofQuaternarystudiesastheyrelatetothePleistocenepeoplingoftheAmericas.

ManuscriptSubmissionsBOOKSTheCentersolicitshigh-qualityoriginalmanuscriptsinEnglish.Forinformationwriteto:RobsonBonnichsen,CenterfortheStudyoftheFirstAmericans,DepartmentofAnthropology,OregonStateUniversity,Corvallis,OR97331orcall(503)737-4596.

CURRENTRESEARCHINTHEPLEISTOCENEResearcherswishingtosubmitsummariesinthisannualserialshouldcontacteditorBradleyT.Lepper,OhioHighSchool,1982VelmaAvenue,Columbus,OH43211-2497orrequestInformationfor

ContributorsfromtheCenter.ThedeadlineforsubmissionisJanuary31ofeachcalendaryear;earlysubmissionissuggested.

MAMMOTHTRUMPETNewofdiscoveries,reportsonrecentconferences,bookreviews,andnewsofcurrentissuesinvited.ContacteditorDonHall,CenterfortheStudyoftheFirstAmericansat(503)745-5203.

ADDITIONALLY...AuthorsareencouragedtosubmitreprintsofpublishedarticlesorcopiesofunpublishedpapersforinclusionintheCenter'sresearchlibrary.Exchangesofrelevantbooksandperiodicalswithotherpublishersisalsoencouraged.PleaseaddresscontributionsandcorrespondencetotheCenter'slibrary.

Pageiii

ThePublicTrustandtheFirstAmericans

RuthannKnudsonBennieC.Keel

Editors

Pageiv

ThepaperinthisbookmeetstheguidelinesforpermanenceanddurabilityoftheCommitteeonProductionGuidelinesforBookLongevityoftheCouncilonLibraryResourcesandtheminimumrequirementsoftheAmericanNationalStandardforPermanenceofPaperforPrintedLibraryMaterialsZ39.48-1984.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

ThepublictrustandtheFirstAmericans/RuthannKnudson&BennieC.Keel,editors.p.cm.PaperspresentedatthePublicTrustSymposiumattheWorldSummitConferenceonthePeoplingoftheAmericas,heldattheUniversityofMaine,Orono,May24-28,1989.Includesbibliographicalreferencesandindex.ISBN0-87071-025-7(alk.paper)1.IndiansofNorthAmericaAntiquitiesCollectionandpreservationCongresses.2.IndiansofNorthAmericaAntiquitiesLawandlegislationCongresses.3.ArchaeologyUnitedStatesMoralandethicalaspectsCongresses.4.Culturalproperty,ProtectionofUnitedStatesCongresses.5.UnitedStatesAntiquitiesCongresses.I.Knudson,Ruthann.II.Keel,BennieC.,1934-.III.CenterfortheStudyoftheFirstAmericans(OregonStateUniversity).IV.PublicTrustSymposium(1989:UniversityofMaine)E77.9.P62199595-7423973.1dc20CIP

Copyright©CenterfortheStudyoftheFirstAmericans1995AllrightsreservedPrintedintheUnitedStatesofAmerica

Pagev

ToHannahMarieWormington1914-1994

"Inthefuture,asinthepast,thegatheringofinformationwilldependtoagreatextentoncooperationbetweenavocationalandprofessionalarchaeologists"H.M.WormingtonColoradoArchaeologicalSociety,1978

Pagevii

FOREWORDDennisStanford

ThisvolumefocusesontheconceptthatthearchaeologicalremainsoftheFirstAmericansarepartofapublictrusttobeprotectedandusedtothebenefitofallpeople:thegeneralpublic,avocationalarchaeologists,NativeAmericans,andprofessionalarchaeologistsalike.Aswithalltrustrelationships,therearemutualresponsibilities.Avocationalarchaeologistsknowthelandanditsresourcesperhapsbetterthandomostprofessionalarchaeologists,whospendmostoftheirtimeteaching,inmuseums,ormanagingpublicandprivateorganizations.Inthisforeword,therelationshipbetweentheavocationalandprofessionalarchaeologistisemphasized.

Thereiscurrentlydistrustamongamateurs,professionalarchaeologists,andNativeAmericanswherepartnershipsareneededtomeetpublictrustresponsibilities.RecentU.S.archaeologicalprotectionlawshaveinhibitedcooperationamongthesegroups,andeffortsneedtobemadetoreestablishconnectionsforinventory,analysis,andinterpretation.Partnershipsarebasedonearnedrespectandmutualexpectations.Forexample,thegeneralpublicaswellasarchaeologistsneedtorespectthespiritualqualitiesofancientNativeAmericansitesandartifacts.AndscientificanalysisofFirstAmericans'physicalremainscanprovidemuchneededinformationimportanttoaddressingmodernNativeAmericanhealthissuesandsupportingadditionalNativeAmericanunderstandingoftheirpast.

Paleoindianstudiesaremultidisciplinaryandrequireavarietyofscientificexpertiseandsignificantlocalknowledge.MostPaleoindiansiteshavebeenfoundandreportedbyavocationalarchaeologistsandinterestedlandownersorbygeologistsinthecourseoftheirresearch.

Oncetheyhavebeenfound,itistheresponsibilityoftheprofessionalarchaeologisttoinsurethatthearchaeologicalinformationis

Pageviii

carefullyrecovered,analyzed,synthesized,reportedinbothtechnicaljournalsandpopularpublications,andmanagedforfuturegenerations.ItistheresponsibilityofalltoseethattheFirstAmericansitesareprotectedfromdevelopmentordestruction.Throughapartnershipinthepublictrustallgroupshaveanopportunitytoparticipateinthepastandhelpbringthepastbacktolifeasanunderstandingofwhoweare,wherewecamefrom,andwhywearethewayweare.

Pageix

PREFACETheWorldSummitConferenceonthePeoplingoftheAmericaswasheldattheUniversityofMaine,Orono,May2428,1989.TheconferencewassponsoredbytheCenterfortheStudyoftheFirstAmericans,thenlocatedwithintheUniversity'sInstituteforQuaternaryStudiesandnowanintegralpartofOregonStateUniversity,Corvallis.MostoftheconferenceconsistedofpresentationsaboutcurrentresearchontheearliestpeopleintheAmericas,butwithintheconferencethePublicTrustSymposiumwasdevotedtounderstandingthepubliccontextinwhichthatresearchisconducted,andinwhichFirstAmericansresourcesareused,preserved,ordestroyed.Thisvolumeincludesthesymposiumpresentations,plusasummaryoftheconferenceresearchpresentations(Bonnichsenetal.)andafinaloverviewonthetopicofthepublictrustandtheFirstAmericans(KeelandCalabrese).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTSManypeoplecontributedtothePublicTrustSymposiumfromwhichthepapersincludedinthisvolumewerederived,andtothetransitionfromasetofspokenideastoacraftedbook.RobsonBonnichsen,DirectoroftheCenterfortheStudyoftheFirstAmericans(CSFA),organizedandchairedtheFirstWorldSummitConference,initiatedtheideaofthePublicTrustSymposiumandhassupporteditspublication.Theeditorsparticularlyappreciatehissupport,andthatofotherCSFAstaffmembersinOrono(LouiseBennett,JudithCooper,andJohnTomenchuk)andCorvallis(PattiGood,RebeccaFoster)from1988untilpublicationofthisvolume.Incomplement,thecontributionsofallsymposiumparticipantsandvolumeauthorsare

alsoacknowledgedwithappreciation.PapersinthisvolumebyBense,Devine,Douglas,Fowler,Gallant,Knudson,Le

Pagex

Master,Magne,McGimsey,Watson,andWilliamswerepresentedorallyinthesymposium.ThepaperherebyMcManamonandKnudsonisbasedonanoralsymposiumpresentationofthesamenamebyGeorgeS.Smith,FrancisP.McManamon,andRichardC.Waldbauer.ThepapersherebyBonnichsenetal.andbyKeelandCalabresewerewrittenspecificallyforthisvolume,andarebasedonotherconferencediscussionsandthesymposiumpresentations.

TheU.S.NationalParkService(NPS)sponsoredthePublicTrustSymposiumandprovidedtravelfundsfromtheU.S.DepartmentoftheInteriorOfficeoftheDepartmentalConsultingArcheologist(ODCA;BennieC.Keel,thenDCA),Washington,DC,underaNPS-UniversityofMaineCooperativeAgreement(CA1600-5-0005)administeredbytheScientificStudiesProgram,NPSNorthAtlanticRegionalOffice,Boston.ThisODCAsupportprovidedtravelexpensestotheconferenceforJudithA.Bense,JohnG.Douglas,RoyGallant,LeslieStarrHart,RuthannKnudson,DennisC.LeMaster,CharlesR.McGimsey,III,GeorgeS.Smith,PattyJoWatson,andSteveWilliams.TheCSFAprovidedtravelsupportforHeatherDevineandMartinP.R.Magne.Expensesofothersymposiumparticipantsweresupportedbytheirhomeinstitutions.

RuthannKnudson'sparticipationpriortoApril1990wasacontributionofKnudsonAssociates,ofwhichsheistheprincipal,exceptforthepreviouslyacknowledgedODCAtravelsupport.HersubsequentinvolvementinthedevelopmentofthisvolumehasbeenacontributionoftheODCAandNPSArcheologicalAssistanceDivision(FrancisP.McManamon,DCAandDivisionChief),andKnudsonAssociates.JeanAlexander,RuthannKnudson,andJoAlexandertechnicallyeditedthevolume.BennieKeel'sinvolvementintheplanningofthesymposiumandpreparationofthisvolumehasalsobeensupportedbytheNPS,througheithertheODCAortheSoutheastArcheologicalCenter,Tallahassee.F.A.Calabrese's

participationinthisvolumehasbeensupportedbytheNPSMidwestArcheologicalCenter,Lincoln.Subventionofthisvolume'sprintingcostswasprovidedbytheODCA.

Pagexi

CONTENTS

ForewordDennisStanford

vii

PrefaceandAcknowledgments ix

I.PublicStewardshipofFirstAmericansResources

TheFirstAmericansandtheNationalParkServiceLeslieStarrHart

3II.ThePublicTrust

ThePublicTrustandArchaeologicalStewardshipRuthannKnudson

9

III.ResearchGuidance

FutureDirectionsinFirstAmericansResearchandManagementRobsonBonnichsen,TomD.Dillehay,GeorgeC.Frison,FumikoIkawa-Smith,RuthannKnudson,D.GentrySteele,AllanR.Taylor,&JohnTomenchuk

30

IV.TheLegalEnvironment

TheLegalStructurefortheProtectionofArchaeologicalResourcesintheUnitedStatesandCanadaJohnM.Fowler

75

Archaeology'sWorld:TheLegalEnvironmentinAsiaandLatinAmericaCharlesR.McGimseyIII

87

GovernmentSupportofArchaeologyinCanadaMartinP.R.Magne

93

AnEnvironmentOutofBalanceDennisC.LeMaster

106

Pagexii

V.PublicEducation

PublicArchaeologicalInformationfromU.S.GovernmentSourcesFrancisP.McManammon&RuthannKnudson

117

SchoolCurriculumandArchaeologyHeatherDevine

127

PublicEducationthroughPublicMediaRoyA.Gallant

140

Public-PrivatePartnershipsinArchaeologyJudithA.Bense

145

VI.Funding

FederalU.S.Funding:FirstAmericansResearchPattyJoWatson

160

SeekingPrivateFundingforAmericanOriginsStephenWilliams

167

FederalU.S.Funding:ResourceandLandManagementSupportJohnG.Douglas

173

VII.Summary

StewardshipofFirstAmericansResourcesBennieC.Keel&F.A.Calabrese

187

ListofContributors 207

Index 209

Page1

IPUBLICSTEWARDSHIPOFFIRSTAMERICANSRESOURCES

first,adj.1.beingbeforeallotherswithrespecttotime...American,adj.5....aninhabitantoftheWesternHemisphere.

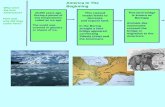

FirstAmericansarethesubjectofpublicfascinationandscholarlyresearch,thatresearchincludingthedevelopmentofmodelsofpasthumanadaptationtochangingworldclimatesandecosystems.Theirarchaeological,geological,andpaleoenvironmentalremainsarenonrenewableoncegone,theyaregoneforever.AcriticalfactoringleaninginformationabouttheFirstAmericansthepeople,theirlifeways,andtheirworldistheinterrelationshipsamongtheseremainsandthecontextsinwhichtheinformationisfound.NothingissimpleaboutunderstandingtheFirstAmericans.

ThisvolumewasdevelopedoutofasymposiumonpublicresponsibilitiesforprotectionofFirstAmericansresources,includingdiscussionsof

theconceptofthatresponsibility;

relationshipsamongresearchersworkingonFirstAmericansresourcesthatareoftenpubliclymanaged,andthoseresourcemanagers;

thelegalbasisforprotectingFirstAmericansresourcesintheAmericasandrelatedmaterialsinAsia;

opportunitiesforeducatingthepublicabouttheFirstAmericansandtheirinformationvalues;and

howtopayforFirstAmericansresearchandprotectionofresources.

Page2

FirstAmericansresources,betheyarchaeologicalornonculturalpaleoenvironmentalsites,collections,orrelatedrecords,arenonrenewableandfinite.Theuseoftheseresourcesmustbecarefullymanaged,conservingwhileatthesametimeexploitingthemtocreatepublicinformation.Aroundtheworld,avarietyofprivateandpublicindividualsandorganizationsmanagetheuseofFirstAmericansmaterials.ThePublicTrustSymposiumwascosponsoredbytheNationalParkServiceandtheCenterfortheStudyoftheFirstAmericans,andfocusedonthepublicnatureoftheseresourcesandthevariousaspectsinvolvedinitswiseuseapublicethicofstewardship,thepubliccontextinwhichresearchisconducted,thelegalenvironmentofresourcemanagement,andpubliceducationaboutandfinancialsupportforresearchandmanagement.TheNationalParkService'sconcernsaboutFirstAmericansresourcestewardship,asexpressedbyLeslieStarrHart,reflecttheneedofmostlandmanagersforinformationaboutFirstAmericansresearchandhowtoprotectFirstAmericansresourcessothatthosemanagerscanbebetterpublicservants.

RUTHANNKNUDSONBENNIEC.KEEL

Page3

TheFirstAmericansandtheNationalParkServiceLeslieStarrHart

TheNationalParkServicerequeststechnicalguidanceregardingtheroleofindigenouspopulationsinFirstAmericansresearch,methodsforachievingcooperationandinformationexchangeamongfederal,tribal,stateandprivatesectorsinArcticresearch,andwaystoenhanceongoinganddevelopinginternationalscientificexchanges.

FederalManagementNeeds

TheU.S.NationalParkService(NPS)'scosponsorshipoftheinternationalmulti-disciplinaryWorldSummitConferenceonthePeoplingoftheAmericas,specificallyofthePublicTrustSymposium,isveryappropriate.Itisobviousthatthesynthesisofscientificinformationandthedelineationofprioritiesresultingfromthesedeliberationswillassistusnotonlyinmanagingarchaeologicalresourcesonourparklandsbut,perhapsmoreimportantly,inoureffortstoprovideleadershipandcoordinationforfederal,tribal,state,andlocalagenciesinmanaging,interpreting,andpreservingthearchaeologicalresourcesthatarethefocusofthismeeting.

(1)Theinvolvementofindigenouspopulations(localresidents)inthedevelopmentandimplementationofresearchinareasthatmayhavedirectbearingontheirabilitytocontinueasubsistence-basedwayoflife.Manyofthesepeople,livinginremoteareas,representcultures''onthebrink";however,theypossessanevolvedcompetencyforsurvivalinastressedenvironmentthatwewoulddowelltoconsiderandlearnfrom.

(2)TheongoingdevelopmentandimplementationofbasicandappliedresearchundertheArcticResearchandPolicyActof1984.

ThisActstressesthecoordinationofArcticresearch,throughinteragencyfederal/stateandprivatesectorcooperationwithrespecttoplanninganddatasharing.Itcould,

Page4

andshould,includeresearchrelatedtothepeoplingoftheAmericas.

(3)Theenhancementofongoinganddevelopinginternationalexchangesamongscientistsandscholars.AlaskahasbeenthebeneficiaryofglasnostwiththeformerUnionofSocialistSovietRepublicsinaverypositivemannersince1987.WehopetoexpandthesecooperativeendeavorsintothecircumpolarandFennoScandiaregionsandbeyond.

BeingassociatedwiththeFirstWorldSummitConferenceprovidesacertainsenseofhistory.OnecannothelpbutwonderwhateffectthiswillhaveontheglobalvisionofAmericanorigins.Fortrulythisisaglobalquestion,onethatoverridesthegeopoliticalboundariespresentlydividingtheplanet.TheseboundarieshaveattimescloudedissuesrelatingtohumanoccupationoftheAmericas,butareovercomebycooperationandexchangeofinformationamongthosewhoseresearchaddressesthepeoplingoftheAmericasinAsia,NorthAmerica,andCentralandSouthAmerica.Althoughtheconferenceisdividedalongthesetraditionallines,Itrustthattheseorganizationalconstructswillprovideacommonground,anacademiclandscape,ifyouwill,onwhichtherecanbeafruitfulexchangeofideasandaconsensusofdirection.

Asamanager,Iamverypleasedtoseethattheconferencenotonlyaddressesquestionsconcerningcurrentresearchanddatagaps,theestablishmentofprioritiesforfutureresearch,thelegalenvironmentforaddressingarchaeologicalresourcemanagement,andfundingforthisresearch,butalsoissuesrelatedtotheprotectionoftheresourceasexemplifiedinconferencetopicsconcerningpubliceducation,preservationofthepublictrust,andthestewardshipofthearchaeologicalrecordthroughouttheAmericas.GiventhefactthatthemajorityofthearchaeologyconductedintheAmericasisfundedbythepublic,itisclearthatthepublichasabigstakeinarchaeology.It

isalsoclearthatprotectionoftheresourcerequirestheactiveparticipationofthepublic.Increasingthepublic'sawarenessofandappreciationforarchaeologywillnodoubtresultinincreasedprotectionofthearchaeologicalresourcebasethroughouttheAmericas.

Page5

Beforewecaneffectivelyprotect,study,andmanagethearchaeologicalresourcebase,wemustdeterminehowbigitisandwhatitconsistsof.EstimatesbyfederalagenciesintheUnitedStatesindicatethatthereareapproximately425,000knownarcheologicalsitesonfederallymanagedU.S.lands.Takeintoconsiderationthatthesesameagenciesreportthatapproximately93percentoftheirlandhasnotbeenexaminedforarchaeologicalsitesandthesizeoftheactualarchaeologicaldatabasewillbeseentobetremendouslyunderstated.Buteventhisconservativeestimate,ofcourse,doesnotincludethestateandprivatelandswhichmakeupapproximatelytwo-thirdsoftheUnitedStates.IfthislevelofsurveyisindicativeofeffortsinotherpartsoftheAmericas,andIthinkitlikelyis,thenwehavealongwaytogointermsofdefiningthearchaeologicalresourcebase.NodoubtmanyofthesitesstillundiscoveredcouldaddressquestionsrelatingtothepeoplingoftheAmericasandoureffortstounderstandthistopicwouldbeenhancedbyresearchdesignedtolocateandinventorythesesites.

InventoryEnhancement

Since1971,U.S.federalagencieshavebeenmandatedtoinventorytheirlandsforarchaeologicalresources.A1988amendment(P.L.100-555)totheArchaeologicalResourcesProtectionActof1979mandatesfederalagenciesto"developplansforsurveyinglandsundertheircontroltodeterminethenatureandextentofarchaeologicalresourcesonthoselands[andto]prepareascheduleforsurveyinglandsthatarelikelytocontainthemostscientificallyvaluablearchaeologicalresources."Althoughmandated,nofundshavetodatebeenallocatedforextensivearchaeologicalinventory(cf.LeMaster,thisvolume).Insteadthechargehasbeentoinventorywithinexistingprogramsandbudgetstodomorewithless.ItisnotsurprisingthatlessthansevenpercentoffederallandsintheUnitedStateshavebeen

surveyedforarchaeologicalsites.Thearchaeologicalresourcesofanevensmallerpercentageof

Page6

AmericanlandsoutsideoftheUnitedStateshavebeeninventoried.

InsettingprioritiesandmakingrecommendationsforarchaeologicalinventoryintheAmericasandotherappropriategeographicalareas,considerationshouldbegiventocooperativeacademic-governmentresearchefforts,perhapsintheformofjointprojectsorstudiesinvolvingscientistsfrommanycountries.TheNPSsupportsthesetypesofcooperativeefforts,andendeavorstoprovideaccesstoNPSlands,information,technicalandlogisticalsupport,andfundingforthesetypesofstudiesatboththenationalandinternationallevelstotheextentthattheycanbearticulatedwithinexistingprograms,responsibilities,andmissions.

Knowing,understanding,andprotectingthearchaeologicalresourcesoftheAmericasisourpermanentandundividedobligationandoneofourmostimportantresponsibilities.Thiswillrequirethecooperationofthosewhostudytheresource,thosewhomanagetheresource,andthosewhoultimatelysupporttheseeffortsthepublic.

Page7

IITHEPUBLICTRUSTTheissueofownershipundoubtedlyhasperplexedtheanimalkingdomsinceitsearliesthistory.Perhapsitisasoldasthekingdomitself.Weknowthatanimalscompeteforspaceandresourcesatthefundamentallevelofexistence.Verysimpleformsofanimallifecompeteforterritoryandprotecttheirspacebymechanismsrangingfromsimpletocomplex.Asanimallifebecomesmoreevolved,complexbehaviorsprotectingtheownershipofterritoryanditsresourcesmovefromtheindividualtothegroup.Tobesure,wearetaughtthatthesebehaviorsaremechanismsforsurvivalandcanbeinterpretedasoperatingatabiologicallevel.Undoubtedly,humanityhasthemostevolved,involved,andcontradictoryconceptsofownershipandproperty.

Anthropologicalstudiestellusthatconceptsofownershipcanincludenotonlythematerialbutthenonmaterial.Weknowthatinsomesocietiesrealestate,houses,businesses,ideas,andconceptscanbeprivatelyheld,butthattherearealsosocietieswherethesesameitemsareownedbythegrouporthestate.Elsewhereonthefaceoftheearthindividualsownorhaveownedspirits,songs,dances,magicalincantationsandthelike,butasindividualspossesslittlematerialwealth.

Page8

Inourlifetimeswehaveseentwopolitico-economicsystemsdominatetheworld.Interestingly,theysharefundamentaldifferencesintheownershipofproperty,especiallypropertythatiswealth-producing.Atthismomentwearelivinginmostinterestingtimesasoneofthesesystemspeacefullyreanalysessomeofitsfundamentaldoctrines.Timewillprovideuswithsomeveryinterestingeventsandsolutionsinthisregard.

Universally,irrespectiveoftheprevailingpoliticalsystem,thepast,thecommonhistoryofanation,isrecognizedasthecommonpropertyofthegroup.Tobesure,howthathistoryisdevelopedandthepurposesforwhichthepastisusedvary,asdoestheownershipofthematerialremainsofthepast.Consideringthecomplexityofconceptsofpropertyandownership,furthercommentsherewillberestrictedtothegeneralareaofarchaeology.

Insomenationstherelicsofthepastarethepropertyofthestate,whereasinothersownershipoftheculturalrelics(andothermaterialevidenceofthepast)belongstothelandowner,pureandsimple.However,thiselementaldichotomyinownershipisrare,aspapersinthisvolumeshow.Aswithotherhumanendeavors,wetendtocreateallkindsofexceptionsandcomplexity.

ThefollowingpaperbyKnudsonespousesanideaofauniversalpublictrustforthepastanditsmaterialmanifestations.Herideasarenotcompletelyoriginal.Archaeologistshavefollowedtheircallingoutoftheirpersonalintellectualneedsorwants;mostofushavenottakenuptheshovelandtroweltobecomerichandfamous.Isuspectthatonlyafterembarkingonthestudyandpracticeofourtradedidwerecognizethatwewerecontributingtothegrandenterpriseofcreatingknowledgeabouttheundeniablecommonthreadofourhumanness.WeareindebtedtoKnudsonforaclearpresentationofthePublicTrustDoctrine.Hopefully,herdiscoursewillserveasadocument

withwhichwecanpersuadeotherstoacceptamoreresponsiblevisionoftheirstewardshipofthepast.

BENNIEC.KEEL

Page9

ThePublicTrustandArchaeologicalStewardshipRuthannKnudson

Inmostmodernsocieties,archaeologicalresourcesareconsideredtobepartofaworldwidepublictrust,beingjointandseverallyownedbythemembersofthehumancommunitywhoallhaverightstotheirheritageinformationandresources.Inthisperspective,allpeoplethushavestewardshipresponsibilitiesfortheserightsandtheseresources,andneedtounderstand,affirm,andimplementthisethic.FirstAmericansarchaeologicalresourcesareaparticularlyimportanttrustelement,becauseoftheirrarityandtheuniqueinformationtheycontainabouthumans'adaptationtoapristineNewWorld.Ultimately,governmentshavearchaeologicalstewardshipresponsibilitiestoactonthepublic'sbehalf.Theseresponsibilitiesmeritclarificationandimplementation,buttheethicalresponsibilitybelongsfirsttotheaveragecitizen.

Beginningwithaleapoffaith,asdoallethicalpositions,Iassertthatarchaeologicalresourcesarepartofaworldwidepublictrust,andthattheyshouldbeused,conserved,and/ordestroyedonlyfollowingconsiderationofthatstewardshipresponsibility.Somesystemsofculturalvaluesdenythisassertion(seeLayton1989),whichIrespect,butthisdiscussionfocusesonwhatIbelieveisadominantworldwidepattern.Underthisscenario,archaeologistshavearesponsibilitytooperateasarchaeologicaltrustees,asdoothermembersofthepublicandprivateworld.ThisisparticularlytruewhendealingwiththeremainsoftheFirstAmericans,whicharerare,oftennotsurfaceevident,andholdirreplaceableinformationaboutourspecies'adaptationtoapristine"NewWorld."

AConceptualFramework

In1986Iinitiatedadiscussionofcontemporaryculturalresourcemanagementwiththequestion,"Whoownsanarchaeologicalsite?"(Knudson1986:395).TherewasnoobviousanswerintheUnitedStates,norindeeddidthereappeartobeoneelsewhereintheworld.Inmakingacomparative

Page10

studyofworldculturalresourcemanagementsystems,Cleere(1984:127)notedthattheprogramsofthosecountriesdiscussedinhisvolumegenerallylackedproperlyconceivedarchaeologicalconservationpolicies.ThisisdespitethefactthattheUnitedNationsEducational,ScientificandCulturalOrganizationadoptedinternationalprinciplesonarchaeologicalexcavationsin1956(UNESCO1985).Cleere'sworkreflectedthelackofanyconsistentethical,muchlessanyformallegal,nationalpoliciesacrosstheworld.

Thisquestionofownership,andconsequentstewardshipresponsibilities,isforemostanethicalissuebut,aswithmostquestionsofrightandwrongandthebalanceofpublicandprivaterights,itsimplementationisalegalquestion.Alegalsystemissimplya(usuallyincomplete)codificationofanethicalvaluesystem.ThispaperdiscusseshowtheUnitedStateshaslegallyaddressedmybasicethicalaffirmation.Subsequentpaperswilladdressarchaeologicalresourcemanagementintheethicalandlegalcontextsofothernations.

Thebasicpropositionsunderlyingarchaeologists'responsibilityforpoliticalparticipationareauniversalethicofpublicarchaeologicalvalues:

(1)Thereisaworldwidemoralconsensusthatthelong-termconservationofasignificantportionofourculturalpastisgoodforthehumancommunity.Asacorollary,lossofournonrenewableheritageresourcebaseengenderssignificantsocialcost(Knudson1984:245).

(2)Thelong-termgoalisconservationofaheritageresourcebaseforthegoodofthehumancommunity,forthepreservationofknowledgeandobjectsastheyholdvalueforlong-termculturalcoherence.Itisnotconservationofanindividualsiteorbuildingperse,orfocusonaspecificresearchtopicoutofcontextofitsrelationshiptotheoverall

culturalneedsofthehumancommunity(Knudson1984:246;cf.Knecht1994).

(3)Whileanimportanthumanvalue,culturalresources(Knudson1986,forthcoming)areonlyoneaspectofahumansocialandeconomicsystem,andallresourcemanagementdecisionsaremaderelativetothebroadersystem;toignorethisbroadpubliccontextisunethical.Thus,archaeologicalresourcesshouldbemanagedwithinamoreinclusivecontext

Page11

ofculturalresourcesand,further,withinthecontextofnational,state,andlocalpublicmulti-resourcepoliciesandprograms(Knudson1984:246).

ThissetofpropositionsdevelopedoutoftheSocietyforAmericanArchaeology's1980BasicPrinciplesofArchaeologicalResourceManagement(Knudson1982).Implicitwithintheseprinciplesisapublictrustconcept.SuchaconceptisalsoimplicitinMcGimsey's(1972:5)seminaldiscussionofpublicarchaeology,andindiscussionssuchasFowler(1986),GradyandLipe(1976),Mayer-Oakes(1989),Schaafsma(1989),TainterandLucas(1983)inWoodall(1989),andZelaya(1981).HavingaconceptlabelornamethePublicTrustisanextremelyimportantmnemonicforproselytizing.Andwemustproselytize,becauseuntilthereisaclearpublicethicalconsensusaboutarchaeologicalvalueswecannotstopthelootinganddestructionofresourcesbydevelopmentforces.

ChristopherChippindalehasnotedthatthisconceptisnotonewithwhichtheBritisharefamiliar,largelybecauseofthestrongmodernpresumptioninEuropeanlawthatlandowners'rightsaretemperedbymanyotherinterests(Chippindale1983).Thatunfamiliarityandlegaldifferenceshouldnotdetractfromtheuniversaladoptionoftheethicandterm.IntheUnitedStates,then-SecretaryoftheInteriorManuelLujan,Jr.(1991)promulgatedANationalStrategyforFederalArchaeologyinwhichhestated,"[Thearchaeologicalpaleoenvironmental]recordisapublictrusttobeunderstoodandevaluatedtohelpshapeourpresentresponsestochangingenvironments."

ThePublicTrustDoctrineinU.S.Law

AsaU.S.citizen,Ihavebeenraisedtorespectthesanctityofprivatepropertyrights,withtheassumedcorollarythatarchaeological

resourcesarethepropertyofthelandowner.ButFirstAmericansresourcesaretoovaluabletoallofustobetreatedaseitherprivatecommoditiesortreasure.OverthepastfewyearsIhavediscoveredthatunderU.S.waterqualitylawsthepublicinterestoftenprevailsoverconstitutionalFifth

Page12

Amendmentpropertyrights.WhynotforFirstAmericansarchaeologicalresourcesaswell?

Since1986,IhaveattemptedtoidentifytheconceptualbasesunderlyingtheUnitedStates'apparentlycontrastinglegalrequirementsforthemanagementofarchaeologicalandwaterresources.ThisattempthasledmetothePublicTrustDoctrine(PTD),anappropriateethicforworldwidearchaeologicalresourcemanagement,thougharelativelyinchoatesetofprincipleswithnoclearconstitutionalbasis.

Lipe(1984:2)hascogentlypointedoutthatarchaeologicalculturalresourceshavevalueonlyasthosevaluesareassignedbyhumanbeings,andthatnotallsuchresourceshave,muchlessareassigned,equallyhighvalue.Archaeologicalresourcesaremostfrequentlyassignedscientific,humanistic,andspiritualvalues(Knudson1991).ThePublicTrustprincipleassertstherightofthewholehumancommunitytopreserveallresourcesuntilavaluejudgmenthasbeenmadeinamannerthatbestservesthepublic'sbroadinterests.

ThefollowingdiscussionofthePTDincludesamorearticulatestatementofaworldwidePublicTrustprinciple,anethicalprescriptforallprivateorpublicindividualsororganizationswhohavesomeinteractionwitharchaeologicalresources.Theacceptanceandimplementationofthisethicalvalueisthefocusofthisdiscussionandsymposium,firstingeneralandsecondarilyinrelationtotheFirstAmericans.Itsexplicitlegalcodificationisasubsidiaryissue,asistheissueofcompensationofprivaterightsinassertingapublicgood.

Heritageintoday'sworldisanownedpast(seeMcGuire1989).Itcomprisesbothmaterialproperty,withactualvalueinanantiquitiesmarket,andinformationaboutpatrimonyandenvironmentaladaptation.Wemustfirstaskwhoownsthisheritage,andthen,secondarily,whocaresforit.

Inourcontemporarylegalisticworldcommunity,stewardshiprightsandresponsibilitiesareexplicitlytiedtopropertyrights.Thislinkageofownershipandstewardshipisincontrasttosometraditionalculturalvaluesystems(forinstance,NezPercemutualcross-utilizationstewardshiprightsandresponsibilities[Walker1967]).Thepublicnatureofarchaeologicalresources,andtheobligationofgovernments,private

Page13

individuals,andorganizationstofulfilltheirresponsibilitiesastrusteesofthesepublicresources,meritsbroaderrecognitionandaffirmation.

In1970,JosephSaxpublishedaseminalpaperonthePTDinU.S.naturalresourcelaw.Naturalresourcelawisdifferentfromenvironmentallawinthattheformerusuallyreferstotheresourceconsumerandthelattertotheresourceprotector(Freedman1987:66).Archaeologicalresourcemanagement,likemineralsmanagement,fallsbetweenthesetwocategorieswhenitisdirectedtotheconservativeconsumptionofanonrenewableresourcebase(cf.Lipe1974,Thompson1974).U.S.federalarchaeologicallaws(e.g.,AntiquitiesActof1906,ArcheologicalandHistoricPreservationActof1974,ArchaeologicalResourcesProtectionAct)areenvironmentalratherthannaturalresourcelaws,prescriptivereactionstothreatsofdamageanddestruction.Thereisnoarchaeologicalresourcelawthatisaproactivestatementofmanagementpolicy(seeDouglas,thisvolume).

Sax(1970:476)pointedoutthatwhilethePTDhaditsoriginsintheRomanJustinianCodeandinMagnaCartapropertyrightsinrivers,seas,andtheshore,

OfalltheconceptsknowntoAmericanlaw,onlythepublictrustdoctrineseemstohavethebreadthandsubstantivecontentwhichmightmakeitusefulasatoolforgeneralapplicationbycitizensseekingtodevelopacomprehensivelegalapproachtoresourcemanagementproblems(Sax1970:474).

BasicallythePTDisamixtureofideasthathavebeensetforthinU.S.caselawsince1821(Stevens1980:199),focusingonSax's(1970:484)concept

...thattherearecertainintereststhatareintrinsicallysoimportanttoeverycitizenthattheirfreeavailabilitytendstomarkthesocietyasoneof

citizensratherthanserfs;toprotectthese,itisnecessarytobeespeciallywarysonoindividualorgroupacquirespowertocontrolthem.

Page14

Sax(1970:485)wentontonotethatprivateuseofthesepubliclysignificantresourcesisoftensoinappropriatethatanindividuallandsurfacetitleownercanonlyhaveusufructownershipofthoseresources,andhencemustrecognizethepublicnatureofarchaeologicalresourceswhichhappentobeonthisproperty.Huffman(1986:571)arguesthatthismaybetrueforwaterbecauseofitsmigratorynature,butprobablyisnotapplicabletononmigratoryresources.However,noonehasexploredtheconcept'slegalapplicationtoheritageresources,muchlessitsexplicitethicalstatement.

Propertyis''thatwhichispeculiarorpropertoanyperson...anaggregateofrightswhichareguaranteedorprotectedbythegovernment"(Black1979).Theessenceofpropertylawisrespectforapropertyholder'sreasonableexpectationsthatherorhisrightscanbeexercised(Reich1964,Sax1980:186-187).Itisassertedherethattheworld'sentirepopulationhasarighttoinformationaboutitshumanheritage(cf.CaliforniaHeritageTaskForce1984:24,DiStefano1988)andthereforeallmembersofthehumancommunityarejointandseverallyownersofallarchaeologicalresources,nomattertheownershipstatusofthedepositionalcontextofthoseresources.Itisthusalogicalcorollarythateachgovernmentorprivateindividualwithlegaljurisdictionoverthephysicalcontextofarchaeologicaldepositshasatrustresponsibilitytoprotectthejointownershiprightsoftheentirehumancommunity.Afurthercorollaryisthatallsitediscoverershavesucharesponsibility.

ThePTDisnotexplicitlyrecognizedintheU.S.Constitutionoritsoriginalsupportingdocuments(Huffman1986:579,Kammen1986).ItsimplicitstatementhasbeentiedtotheNinthAmendment"TheenumerationintheConstitution,ofcertainrights,shallnotbeconstruedtodenyordisparageothersretainedbythepeople"asa"righttoadecentenvironment"(Freedman1987:32-35,Sloan

1979:63;cf.Adler1988).

ThePTDhasalsobeentied(Sax1980,Wilkinson1980:311)tothePropertyClauseoftheU.S.Constitution(Art.IV,Sec.3,Para.2):

TheCongressshallhavePowertodisposeofandmakeallneedfulRulesandRegulationsrespectingthe

Page15

TerritoryorotherPropertybelongingtotheUnitedStates....

However,thePropertyClausehasbeenonlyinfrequentlyappliedtotheregulationofprivateproperty(Reed1986,Shepard1984),andmoreoftensuchregulationhasreliedonwhatisgenerallyknownasthe"policepower"toregulatepublicnuisances(Grad1971:1-15,Humbach1987:561,Sax1964).

Inaddition,theFourteenthAmendment

...NoStateshallmakeorenforceanylawwhichshallabridgetheprivilegesorimmunitiesofcitizensoftheUnitedStates;norshallanyStatedepriveanypersonoflife,liberty,orproperty,withoutdueprocessoflaw;nordenytoanypersonwithinitsjurisdictiontheequalprotectionofthelaws(Sec.1).

hasbeencitedasabasisforthePTD.

Somestates(California,NewJersey,Illinois,Wisconsin,Florida,Louisiana,Massachusetts,NorthDakota,andOregon)haveexpresslycodifiedthePTDinrelationtospecifiednaturalresources(Huffman1986:572,Wilson1984).InLouisiana,thisspecificallyincludesthe"healthful,scenic,historicandaestheticqualityoftheenvironment"(Freedman1987:230).

Untilrecently,therehadbeenlittleexplicitlegalconfrontationbetweenthePTDandthetakingissueorJustCompensationClauseoftheFifthAmendment(Bosselmanetal.1973,thoughseeReagan1988,U.S.DepartmentoftheInteriorSolicitor1979).ThatAmendmentstatesthatnopropertyshallbetakenforpublicusewithoutduecompensation.Thereclearlyhavebeenethicalconfrontationsbetweenthetwoperspectives,asinarchaeologicalminingofprivatelands.Similarly,thereareconflictsbetweensurfaceownershiprightsandtherightsofAmericanIndiansinthedispositionofIndianhumanremainsandassociatedfuneraryitems(Price

1991:23-24).

Humbach(1987:551-553)pointsoutthattherearetwotypesofpropertyintereststhatcanbetaken:propertyrights(legaladvantageanownerhasbecauseoflegaldutiesimposedonothers[e.g.,notrespass])andpropertyfreedoms(legaladvantageofbeingabletodowhatonewantsonone'sproperty).

Page16

TheSupremeCourthasrarelyrequiredcompensationoffreedomtakingssuchasmayoccurthroughgeneralzoning,althoughExecutiveOrder12630statesthatsuchgovernmentalactionsmayrequirecompensation(Reagan1988:347).However,newscholarlyattentionisbeingpaidtothesocialbenefitsofcommonownershipofnaturalresources(McCayandAcheson1987),andthetradeoffsinbalancingpropertyrightsandjustice(Goldfarb1988,Sagoff1988).FormerU.SSupremeCourtJusticeWilliamJ.Brennan,whowasmostinfluentialinrulingsonhistoricbuildingpreservationvs.privatepropertyrights,heldtothefollowinglanduseproposition:

Althoughtheindividual'srighttodevelopanduseprivatepropertymaybeseverelylimitedbyrightsofthecommunity,theindividualinalleventsisentitledtoanexpectationofreasonableeconomicuseandmustreceivecompensationforlossofvalueifaregulationgoestoofar(HaarandKayden1991:15).

Andfurther:

Wemustdistinguishthoseproperty"rights"thatrelatetotheuse,enjoyment,privacy,therighttoenforcetrespass,andtherighttodisposeofandinheritlandfromthe"right"togainthehighestandimmediatedollarreturnbasedonexpectancyorspeculativevalue(Collins1991;cfWeber1991).

Thereisundeniableethicalandlegaltensionbetweenthesetwoconcepts,andeachgovernmentalandprivatelandownerdecisionaboutresourceusemustinvolveacase-specificbalancingofcompetinguses(Stevens1980:223).ThereisaneedtoreconcilethePublicTrustwithacommunity'srighttothebenefitsofprivateownership(Wilson1984:897).But,asJohnGardner(1960:23)hasnoted:

Ourpluralisticphilosophyinviteseachorganization,institution,orspecialgrouptodevelopandenhanceitsownpotentialities.Butthepriceofthattreasuredautonomyandself-preoccupationisthateachinstitutionconcern

itselfalsowiththecommongood.Thisisnotidealism;itisself-preservation[italicsintheoriginal].

Page17

ApplicationofthePTDtoU.S.historicarchitecturalpropertieshasbeenaspecialissuesincetheSupremeCourtPennCentralcasein1978,whichrenderedadecisionthat

...standsforthepropositionthattherightsincidenttopropertyownershiparenotabsolute,butaresubjecttoreasonableregulationforthebenefitofthecommunitywithoutthenecessityofrequiringthepublictopaymonetarycompensation[Doheny1993:8].

Recently,JosephSaxhasaddressedtheapplicationofthePTDtothepreservationofhistoricproperties,assertingthat"Propertyrightsclaimsdonotstandasasignificantbarriertoprotectionofculturalproperties"(Sax1993:137).WhenU.S.courtsconsidertheconflictbetweenindividualfreedomandthevaluesofacommunitywitheitherasharedcultureordiversecultureswithinthelargersociety,overtimetheyhavequietlysupportedtheprotectionofheritagevalues.

TheU.S.courtscontinuetorefinethejudicialinterpretationoftheFifthAmendmentJustCompensationClause(Harper1994,Roddewig1993),andtherecontinuestobeconsiderablemisunderstandingintheUnitedStatesofthedifferencebetweenpropertyrightsandpropertyvalues(Rypkema1993).ThebuiltenvironmentcommunitywithintheU.S.historicpreservationprogramhasrecentlyarticulatedmorecarefullyitsbeliefintheappropriatenessofapplyingthePTDtothatprogram.Recentpapersrelatehistoricpreservationtocivicresponsibilitiesforstewardship,managingtheimpactofchangeonpeopleandtheirenvironmentandvalueconflictsbetweenindividualsandcommunity(Beaumont1993);toopenspaceprotection(DehartandFrobouck1993);andtoqualityoflife(Lewis1993).TodatethesediscussionshaveaddressedtheapplicationofthePTDonlytosubmergedarchaeologicalresources(Dentonetal.1993),andnotbroaderissues,muchlessthearchaeologicalresourcesofindigenouspeople(cf.Brush1993).AllFirstAmericansscholarsandother

enthusiastshavearesponsibilitytoparticipateintheapplicationofthePublicTrustconcepttothefullrangeofcultural(Hufford1990,1994)andnaturalheritageresources,includingthebuiltenvironment.

Page18

InOctober1993,a"carefullyplanned,no-holds-barredstrategysession"washeldinSundance,Utah,toaddressthetakingsissue,theparticipantsbeingwesternU.S.statelegislators,environmentalandconservationleaders,environmentallobbyists,andunionleaders(MacWilliamsCosgroveSnider1994).WhileFirstAmericanspreservationconcernswerenotdiscussedspecifically,theSundanceConferenceandcoalitionareanappropriatesociopoliticalforuminwhichtoaddressthoseconcerns.

Beforearchaeologicalsitesonpublicorprivatelandscanconsistentlybethesubjectofpublicdecisions,theirmembershipwithinaninalienablepublictrustmustberecognizedbybotharchaeologistsandnon-archaeologists.Thischangemustbecomplementedbyachangeinthepublic'sperceptionofarchaeology'sintrinsicnatureandvalues.

Stewardship

StewardshiphasbeenusedtostandforarchaeologicalsiteprotectionandconservationintheUnitedStatesforatleastthepasttwodecades;itmayhavebeencommonearlier,butIwasnotfamiliarwithit.Thedictionarydefinesstewardas"apersonwhomanagesanother'spropertyorfinancialaffairs,orwhoadministersanythingastheagentofanotherorothers"(Stein1975:1289).Inusingtheterm,archaeologistsimplicitlyaffirmthatarchaeologicalresourcesaresomeone'spropertywithoutdealingexplicitlywiththeconceptsofownershiprightsandresponsibilities.Thesemustbeaddressedbeforethequestionofwhomanagestheproperty,andhowisittobedone,canbeadequatelyaddressed.

Myinitialassertionincludedtheconceptofapublictrust,notjustapublicinterest.Identifyingsomethingasbeinginthepublic'sinterestisastatementofacollectiveethic,buthasnoenforcementmechanism.Whoaregoingtobethestewardsofthispublicinterest?

TheconceptofaPublicTrustrequiresanagentofaction,atrusteeofthepublicinterest.

Page19

WhileIbelievearchaeologicalresourceshavemorescientific,humanistic,andspiritualvaluethangenerallyisperceived,theirapparentinertnessandinabilitytodoworkmeansthattheaveragecitizenseesthemascuriositiesbutnotasignificantfactorintradeoffsthatdohaveeconomicbenefit(Knudson1989a).Atpresent,theaveragecitizenisunlikelytobeastewardofarchaeologicalresourcesorthepublicrightsrelatedtothem.InthelongrunthereprobablyisaneedforlegalcodificationofthePublicTrustconceptasitappliestoarchaeologicalresources.First,though,archaeologistsandotherconcernedcitizensmustaffirmandarticulatetheconceptofpeopleaspublictrustees,toenhanceinformalstewardship.Acceptanceofthisethicwillinturndevelopaconstituencyforapossiblynecessaryfuturepoliticalcampaign.And,secondarilybutbeforecodification,theeconomicbenefitsandcostsofarchaeologicalmanagementandconsumptionmustbearticulatedtoprovideavalidbasisfordebatesovertradeoffsandcompensation(Schmid1989;cf.Cantor1991,ChappelleandWebster1993,Lutz1993,Tietenberg1992;seeKnudsonforthcoming).

ManuelLujan,Jr.,U.S.SecretaryoftheInteriorfrom1988to1992,establishedaten-pointagendaforthedepartmentunderthethemeofSTEWARDSHIP(Greenberg1989).Thefocuswasoriginallyonnaturalresources,butin1991theSecretarypromulgatedhisNationalStrategyforFederalArcheology(Lujan1991),complementinghisearlieragenda.Itisimperativethatthearchaeologicalcommunitycontinuetoeducateitspoliticalleadersabouttheneedtokeepastewardshipfocusonourculturalresources.

Mostimportanttoeffectivearchaeologicalstewardshipisthepublic'sperceptionofthepublictrust,includingprivatelandowners'participationinarchaeologicalresourcemanagementacrossthecountryandworld.Conservationofarchaeologicalsitesinplace,orcollectionofinformationandartifactsexcavatedtoallowother

resourceuses,whileconsideringtheprivateinterestsofrelatedindividuals,isresponsibleexecutionofapublictrust.Itcanbringbenefitsbycontributingscientificknowledge(oftenaboutissuessuchas

Page20

wastemanagementmethodsanddesiredfutureecosystemconditionsaswellasaboutculturalheritage),heritagecontinuities,goodpublicrelations,recreation,ortourismopportunities.

FirstAmericansResourceswithinthePublicTrust

FirstAmericansarchaeologicalresourcesareanirreplaceablerecordofhumanadaptationtoapristinenaturalNewWorld,onenotmodifiedbyoilspills,nuclearwaste,municipallandfills,oracidrain.Interdisciplinarystudiessuchasthosedescribedthroughoutthisconferenceprovideauniquerecordofhumantechnologicalandsocioculturalgrowthanddevelopmentandpaleoenvironmentalconditions.TheycanprovideasignificantdatabaseforbetterunderstandingrelationshipsbetweenpeopleandtheirenvironmentintheArtic,whichhasbeenidentifiedasatopprioritybytheCommitteeonArcticSocialSciences(1989).Theycanprovidesimilarinformationinotherenvironments,andinthebroadeststudiesofglobalclimaticandecologicalchange(cf.EarthSystemSciencesCommittee1988,MaloneandCorell1989:33).Nuclearwastemustbedisposedoftobesafefor10,000years;mostpeoplehavenoconceptof10,000years,muchlesshowtodesignengineeredsystemsthatprovidethatsafety.Archaeologicalstudiescandoworkinareassuchasthese,ifarchaeologistsunderstandthequestionsthatneedtobeaddressed,andcanhelptosearchforsomeanswerswhiledoingpersonallysatisfyingresearch.

FirstAmericansresourcesarerelativelyrare,oftennotsurfaceevident,andoftendonotincludesuchspectacularfeaturesorartifactsthattheyacquireanimmediatepublicfanclub.TheycanbeconservedonlywithinaPublicTrustconcept.

Page21

SummaryandConclusions

Archaeologicalresourcesarepartofapublictrust,beingjointandseverallyownedbythemembersoftheuniversalhumancommunity.Affirmativestewardshipofallarchaeologicalmaterialsmustincludearchaeologicaleducationofthegeneralpublic,politicians,NativeAmericans,andotherinterestgroupsinadditionto,ifnotbefore,thephysicalmanagementofthesitesandartifacts.

Archaeologyalsoneedstoberecognizedaspartofthegeneralenvironmentalmanagementequation,becauseofitspublicnatureaspartofatrustmanagedbybothprivateindividualsandgovernments,beforetherearenositesleftaboutwhichtoworry(Knudson1989b).Atthesametime,theU.S.FifthandFourteenthAmendmentsconcerningpropertyrightsneedtobeaddressedinspecificmultiresourcemanagementdecisionsthatinvolvearchaeology.U.S.societyisbasedonthegenerationofwealththroughtheuseofnaturalresourcesthatarethemselvesalsoelementsofthepublictrust;resourcemanagementisthusalwaysabalancingofcompetinggoalsandinterests.

Acknowledgements

IamindebtedtoRogerRyman,retiredManager,LandandEnvironment,ShellPipeLineCompany,whofirstforcedmetoconfronttheissueofarchaeologicalsiteownershipandmanagementresponsibilitywhenIwasworkingwithhimontheCortezPipelineproject.StevenE.James,VicePresident,Woodward-ClydeConsultants,ledmetotheconceptofthePublicTrustDoctrine.TheUniversityofIdahoCollegeofLawLibrarywasinvaluableinmybackgroundresearchonthedoctrine,andArthurD.Smith,Jr.,AssociateDeanoftheCollege,wasaninterestedsupporterofthatresearch.Subsequentparticipationinthe1990CulturalConservation

ConferencesponsoredbytheAmericanFolklifeCenter,U.S.LibraryofCongress,Washington;the1991annualmeetingoftheNationalAssociationofEnvironmentalProfessionalsinBaltimore;and1992-1993discussionsonpropertyrightsandhistoricpreservationwithPreservationActionandtheNationalTrustforHistoricPreservation,Washington,havebeeninvaluableinassistingmetounderstandthecontextofhowthePTDcanbeimplemented.

Page22

ReferencesCited

Adler,M.J.

1988WeHoldTheseTruths.TheCommonwealth82:108-111.

Beaumont,C.E.

1993PropertyRightsandCivicResponsibilities.HistoricPreservationForum7(4):30-35.

Black,H.C.

1979Black'sDictionary(5thed.).WestPublishingCompany,St.Paul.

Bosselman,F.,D.Callies,andJ.Banta

1973TheTakingIssue.CouncilonEnvironmentalQuality,Washington.

Brush,S.B.

1993IndigenousKnowledgeofBiologicalResourcesandIntellectualPropertyRights:TheRoleofAnthropology.AmericanAnthropologist95:653-686.

CaliforniaHeritageTaskForce

1984CaliforniaHeritageTaskForce.AReporttotheLegislatureandPeopleofCalifornia.CaliforniaHeritageTaskForce,Sacramento.

Cantor,R.

1991

BeyondtheMarket:RecentRegulatoryResponsestotheExternalitiesofEnergyProduction.Proceedingsofthe1991ConferenceoftheNationalAssociationofEnvironmentalProfessionals,editedbyD.B.Hunsaker,Jr.,andG.F.Kelman,pp.G51throughG61.NationalAssociationofEnvironmentalProfessionals,Washington.

Chappelle,D.E.,andH.H.Webster

1993ConsistentValuationofNaturalResourceOutputstoAdvanceBothEconomicDevelopmentandEnvironmentalProtection.RenewableResourcesJournal11(4):14-17.

Chippindale,C.

1983TheMakingoftheFirstAncientMonumentsAct,1882,anditsAdministrationunderGeneralPitt-Rivers.JournaloftheBritishArchaeologicalAssociation136:1-55.

Cleere,H.

1984WorldCulturalResourceManagement:ProblemsandPerspectives.InApproachestotheArchaeologicalHeritage,editedbyH.Cleere,pp.125-131.CambridgeUniversityPress,Cambridge.

Page23

Collins,R.C.

1991LandUseEthicsandPropertyRights.JournalofSoilandWaterConservation46(6):417-418.

CommitteeonArcticSocialSciences

1989ArcticSocialScience:AnAgendaforAction.CommitteeonArcticSocialSciences,PolarResearchBoard,CommissiononPhysicalSciences,Mathematics,andResources,NationalResearchCouncil,Washington.

Dehart,H.G.,andJ.A.Frobouck

1993PreservingPublicInterestsandPropertyRights.HistoricPreservationForum7(4):36-46.

Denton,S.,C.A.Shafer,andL.L.Leighty

1993ThePublicTrustDoctrine:HowMayItApplytoShipwrecksandOtherUnderwaterCulturalResources?InGreatLakesUnderwaterCulturalResources:ImportantInformationforShapingOurFuture,editedbyK.J.VranaandE.Mahoney,AppendixC.DepartmentofParkandRecreationResources,MichiganStateUniversity,EastLansing.

DiStefano,R.

1988Editorial.ICOMOSInformation,No.3(1988).

Doheny,D.A.

1993PropertyRightsandHistoricPreservation.HistoricPreservationForum7(4):77-10.

EarthSystemSciencesCommittee,NASAAdvisoryCouncil

1988EarthSystemScience:AProgramforGlobalChange.NationalAeronauticsandSpaceAdministration,Washington.

Fowler,D.F.

1986ConservingAmericanArchaeologicalResources.InAmericanArchaeologyPastandFuture,editedbyD.J.Meltzer,D.D.Fowler,andJ.ASabloff,pp.135-162.SmithsonianInstitutionPress,Washington.

Freedman,W.

1987HazardousWasteLiability.TheMichieCompany,Charlottesville,Virginia.

Gardner,J.

1960Leadership:aSampleroftheWisdomofJohnGardner.HubertH.HumphreyInstituteofPublicAffairs,UniversityofMinnesota,Minneapolis.

Goldfarb,W.

1988LitigationandLegislation:TakingandthePublicTrustDoctrine.WaterResourcesBulletin24:1133-1134.

Page24

Gard,F.P.

1971EnvironmentalLaw.MatthewBender,NewYork.

Grady,M.,andW.Lipe

1976TheRoleofPreservationinConservationArchaeology.AmericanSocietyforConservationArchaeologyProceedings1976:1-11.

Greenberg,R.M.(editor)

1989StewardshipofAmerica'sPublicLandsandNaturalResources.CRMBulletin12(1):24.

Haar,C.M.,andJ.S.Kayden

1991LandmarkJustice.TheInfluenceofWilliamJ.BrennanonAmerica'sCommunities.ThePreservationPress,Washington.

Harper,L.A.

1994ANewViewofRegulatoryTakings?Environment36(1):205,39-40.

Huffman,J.L.

1986TrustingthePublicInteresttoJudges:ACommentonthePublicTrustWritingsofProfessorsSax,Wilkinson,Dunning,andJohnson.DenverUniversityLawReview63:565-584.

Hufford,M.

1990ReconfiguringtheCulturalMission:AReportontheFirstNationalCulturalConservationConference.FolklifeCenterNews7(3-4):3-7.

(editor)

1994ConservingCulture:ANewDiscourseonHeritage.UniversityofIllinoisPress,Urbana.

Humbach,J.A.

1987ConstitutionalLimitsonthePowertoTakePrivateProperty:PublicPurposeandPublicUse.OregonLawReview66:547-598.

Kammen,M.(editor)

1986TheOriginsoftheAmericanConstitution.PenguinBooks,NewYork.

Knecht,R.

1994ArchaeologyandAlutiiqCulturalIdentityonKodiakIsland.SocietyforAmericanArchaeologyBulletin12(5):8-10.

Knudson,R.

1982BasicPrinciplesofArchaeologicalResourceManagement.AmericanAntiquity47(1):163-166.

Page25

1984EthicalDecisionMakingandParticipationinthePoliticsofArchaeology.InEthicsandValuesinArchaeology,editedbyE.L.Green,pp.243-263.TheFreePress,Collier-Macmillan,NewYork.

1986ContemporaryCulturalResourceManagement.InAmericanArchaeologyPastandPresent,editedbyD.J.Meltzer,D.D.Fowler,andJ.B.Sabloff,pp.395-413.SmithsonianInstitutionPress,Washington.

1991TheArchaeologicalPublicTrustinContext.InProtectingthePast,editedbyG.S.SmithandJ.E.Ehrenhard,pp.3-8.CRCPress,BocaRaton,Florida.

Forthcoming.CulturalResourcesinthe1990s.InAdvancesinScienceandTechnologyforHistoricPreservation[AdvancesinArchaeologicalandMuseumScienceSeries],editedbyR.A.Williamson.PlenumCorporation,NewYork.

Layton,R.(editor)

1989ConflictintheArchaeologyofLivingTraditions.UnwinHyman,London.

Lewis,T.A.

1993PropertyRightsandHumanRights.HistoricPreservationForum7(4):47-51.

Lipe,W.D.

1974

AConservationModelforAmericanArchaeology.Kiva39:213-245.

1984ValueandMeaninginCulturalResources.InApproachestotheArchaeologicalHeritage,editedbyH.Cleere,pp.1-11.CambridgeUniversityPress,Cambridge.

Lujan,Jr.,M.

1991ANationalStrategyforFederalArcheology.PolicyStatement,SecretaryoftheInterior,U.S.DepartmentoftheInterior,Washington.(Reprinted,SAABulletin10:10,15[1992].)

Lutz,E.(editor)

1993TowardImprovedAccountingfortheEnvironment.TheWorldBank,Washington.

MacWilliamsCosgroveSnider

1994TheSundanceConference.RockyMountainStates''Takings"StrategyMeeting.AmericansfortheEnvironment,Washington.

Malone,T.R.,andR.Corell

1989MissiontoPlanetEarthRevisited.Environment31:6-11,31-35.

Page26

Mayer-Oakes,W.J.

1989Science,Service,andStewardship--ABasisfortheIdealArchaeologyoftheFuture.InArchaeologicalHeitageManagementintheModernWorld,editedbyH.F.Cleere,pp.52-58.UnwinHyman,London.

McCay,B.J.,andJ.M.Acheson(editors)

1987TheCultureandEcologyofCommunalResources.UniversityofArizonaPress,Tucson.

McGimsey,C.R.III

1972PublicArchaeology.SeminarPress,NewYork.

McGuire,R.H.

1989ArchaeologyandtheVanishingAmerican.FirstJointArchaeologicalCongress,Abstracts:141.Baltimore,Maryland.

Price,H.M.,III

1991DisputingtheDead.U.S.LawonAboriginalRemainsandGraveGoods.UniversityofMissouriPress,Columbia.

Reagan,R.

1988ExecutiveOrder12630--GovernmentalActionsandInterferenceWithConstitutionallyProtectedPropertyRights.March16,1988.AdministrationofronaldReagan,1988:347-350.

Reed,S.W.

1986ThePublicTrustDoctrine:IsItAmphibious?JournalofEnvironmentalLawandLitigation1:107-122.

Reich,C.

1964TheNewProperty.YaleLawJournal73:33ff.

Roddewig,R.J.

1993HistoricPreservationandtheConstitution.HistoricPreservationForum7(4):11-22.

Rypkema,D.D.

1993PropertyRights/PropertyValues.HistoricPreservationForum7(4):23-29.

Sagoff,M.

1988EnvironmentalProtectionandPropertyRights.ForumforAppliedResearchandPublicPolicy3:75-84.

Sax,J.L.

1964TakingsandthePolicePower.YaleLawJournal74:36-76.

1970ThePublicTrustDoctrineinNaturalResourceLaw:EffectiveJudicialIntervention.MichiganLawReview68:471-566.

Page27

1980LiberatingthePublicTrustDoctrineFromItsHistoricalShackles.U.C.DavisLawReview14:185-194.

1993PropertyRightsandPublicBenefits.InPastMeetsFuture:SavingAmerica'sHistoricEnvironments,editedbyA.J.Lee,pp.137-143.ThePreservationPress,Washington.

Schaafsma,C.F.

1989SignificantUntilProvenOtherwise:ProblemsVersusRepresentativeSamples.InArchaeologicalHeritageManagementintheModernWorld,editedbyH.F.Cleere,pp.38-51.UnwinHyman,London.

Schmid,A.A.

1989Benefit-CostAnalysis:APoliticalEconomyApproach.WestviewPress,Boulder,Colorado.

Shepard,B.

1984TheScopeofCongress'ConstitutionalPowerUnderthePropertyClause:RegulatingNon-FederalPropertytoFurtherthePurposesofNationalParksandWildernessAreas.BostonCollegeEnvironmentalAffairs,11:479-538.

Sloan,I.J.

1979EnvironmentandtheLaw.OceanaPublications,Inc.,DobbsFerry,NewYork.

Stein,J.(editor-in-chief)

1975TheRandomHouseCollegeDictionary,rev.ed.RandomHouse,Inc.,NewYork.

Stevens,J.S.

1980ThePublicTrust:ASovereign'sAncientPrerogativesBecomethePeople'sEnvironmentalRight.U.C.DavisLawReview14:195-232.

Tainter,J.A.,andG.J.Lucas

1983EpistemologyoftheSignificanceConcept.AmericanAntiquity48:707-719.

Thompson,R.H.

1974InstitutionalResponsibilitiesinConservationArchaeology.InProceedingsofthe1974CulturalResourceManagementConference,editedbyW.D.LipeandA.J.Lindsay,Jr.,pp.13-24.MuseumofNorthernArizona-TechnicalSeriesNo.14.

Tietenberg,T.

1992EnvironmentalandNaturalResourceEconomics.3rded.HarperCollinsPublishersInc.,NewYork.

Page28

UnitedNationsEducational,ScientificandCulturalOrganization(UNESCO)

1985[1983]RecommendationonInternationalPrinciplesApplicabletoArcheologicalExcavations.InConventionsandRecommendationsofUnescoConcerningtheProtectionoftheCulturalHeritage,pp.101-115.UnitedNationsEducational,ScientificandCulturalOrganization,Paris.

U.S.DepartmentoftheInteriorSolicitor

1979TheExtenttoWhichtheNationalHistoricPreservationActRequiresCulturalResourcestobeIdentifiedandConsideredintheGrantofaFederalRight-of-Way.MemorandumtotheSecretaryoftheInterior,December6,1979.U.S.DepartmentoftheInterior,Washington.

Walker,D.E.,Jr.

1967MutualCross-UtilizationofEconomicResourcesinthePlateau:AnExamplefromAboriginalNezPerceFishingPractices.WashingtonStateUniversityLaboratoryofAnthropologyReportsofInvestigationNo.41.

Weber,L.J.

1991TheSocialResponsibilityofLandOwnership.JournalofForestry89(4):12-25.

Wilkinson,C.F.

1980

ThePublicTrustDoctrineinPublicLandLaw.U.C.DavisLawReview14(2):269-316.

Wilson,H.J.

1984ThePublicTrustDoctrineinMassachusettsLandLaw.BostonCollegeEnvironmentalAffairsLawRev.11(4):839-899.

Woodall,J.N.(editor)

1989Predicaments,Pragmatics,andProfessionalism:EthicalConductinArcheology.SpecialPublicationNo.1.SocietyofProfessionalArcheologists,OklahomaCity.

Zelaya,J.L.

1982TheOASasPreserveroftheCulturalHeritage.InRescueArcheology:PapersfromtheFirstNewWorldConferenceonRescueArcheology,editedbyR.L.WilsonandG.Loyola,pp.11-17.ThePreservationPress,Washington.

Page29

IIIRESEARCHGUIDANCEThefocusoftheFirstWorldSummitConferenceonthePeoplingoftheAmericaswascurrentresearchinFirstAmericansstudies,andthosepapersarepresentedindetailinfourotherproceedingsvolumes.AsecondconferencethemewasthepubliccontextinwhichFirstAmericansresourcesarestudied,used,managed,anddestroyed.ThefollowingpaperbyBonnichsenetal.isasummaryofcurrentandfutureFirstAmericansresearchneedsinthatcontextofpublicmanagement.

BENNIEC.KEEL

Page30

FutureDirectionsinFirstAmericansResearchandManagementRobsonBonnichsen,TomD.Dillehay,GeorgeC.Frison,FumikoIkawa-Smith,RuthannKnudson,D.GentrySteele,AllanR.Taylor,&JohnTomenchuk

FirstAmericansresearchhascomeofageandprovidesprimarydataimportantforunderstandinglocal,regional,andglobaldynamicsandlinkagesamongpastclimates,ecologies,andhumanadaptations.Bettersitereportsandanalyticalhypothesesneedtobedeveloped,alongwithstandardizedclassificationanddescriptivetechniques.Bioanthropologicalstudiesneedtomakebetteruseoftheavailablesampleofearlymodernhumanskeletalmaterial,andtodevelopmoreaccuratemodelsofbiologicalrelationships.Additionalmethods,relyingonstatisticsandvariouskindsoftypologies,areneededtodealwithlinguisticresemblancestoevaluaterelationshipsamongindigenousAmericanandAsianpopulations,andSouthAmericanlanguagesneedtobedocumentedmorefully.Thetraditionallinkbetweenscholarlyandpublicarchaeologyneedstobere-established,becausepubliclandandresourcemanagementisthecontextforFirstAmericansresourcemanagementandresearchinNorthAmericaandothernations.PublicoutreachandarchaeologicaleducationarevitalelementsinconservationandcontinuedstudyofFirstAmericansresources,andtheNativeAmericancommunityshouldbemoreinvolvedinFirstAmericansstudy.ThecomingofageofFirstAmericansresearchinvolvesaffirmativepartnershipswithotherpublicandprivatestewardsoftheheritagepublictrust.

Aswestandatthethresholdofthetwenty-firstcentury,ourworldisa

globalvillage.Sophisticatedinformationtechnologiesprovidedbysatelliteimagery,electroniccommunication,andcomputertechnologyareprofoundlyaffectinghowweperceive,analyze,andcomprehendtheworldaroundus.Intheglobalvillage,wearebecomingmoreawareofourindividualresponsibilitiesasscholarsofpubliclyvaluedarchaeologicalinformation,andasmanagersofpubliclyvaluedarchaeologicalmaterials.

Withthedevelopmentofspace-agetechnology,wearenownotonlycapableofgaininganevenmorecomprehensiveunderstandingofhowtheearthanditsculturesfunction,butalsoofprobingtheremotepastanddevelopingamorerealistic

Page31

understandingoftheoriginanddispersalofmodernhumans.Centraltothisendeavorisarchaeology'sgreatunansweredquestionofwhenandhowtheAmericaswereinitiallypeopled.Adefinitiveanswertothisglobalproblemisnotyetinhand,thoughanumberofsignificantscientificadvanceshavebeenmadeoverthelasttwodecades.Yetmostpeopleareunawareoftheseadvances.

Developingandintegratingintosocietyscientificknowledgeaboutourhumanheritageinvolvesresearch,conservation,andpubliceducation,aswellaspublicpolicytoguideandintegratethesecomponents.Asamajorstepinthisprocess,theCenterfortheStudyoftheFirstAmericans(CSFA)convenedtheFirstWorldSummitConferenceonthePeoplingoftheAmericasduringMay1989(Summit'89)tosynthesizescientificknowledgeaboutearlyAmericanorigins.ScientificresearchspecialistsfromAsia,NorthAmerica,andSouthAmericaparticipatedintheconferenceandhavecontributedpapersforfoureditedvolumesrelatingtomethodandtheory,theIceAgeprehistoryofNorthAmericaandSouthAmerica,andtheIceAgeenvironmentsandtheprehistoryofAsia(BonnichsenandSteele1994,Bonnichsenetal.forthcoming(a)and(b),BonnichsenandDillehayforthcoming).WithinSummit'89,asymposium,"ThePublicTrustandtheFirstAmericans,"focusedonthepubliclegalandeducationalenvironmentsnecessarytosupportresearchontheAmericas'earliestculturalheritage,conserveFirstAmericansresources,andeducatetheworld'speoplesaboutthisuniquelegacy.Thisvolumeincludesthespecialsymposiumproceedings,andthispapersummarizesthescientificandpubliccontextoftheconferenceinwhichthediscussionsofpublicresponsibilityoccurred.

Scientificresearchdrivesthedevelopmentofnewknowledge.Yetoften,asinthecaseofFirstAmericansstudies,manyimportantresultsarenotdisseminatedtootherscientists,integratedintoresourcemanagementpractices,ormadeavailabletothepublicandschool

educators.BuildingfromresultsofinformationdevelopedinconjunctionwithSummit'89,thepurposeofthispaperisto:(1)outlinepotentialfutureresearchdirectionsimportanttounderstandingtheoriginandspreadofIceAgepeoplesandtheirculturesintotheAmericas;

Page32

(2)discusspublicstewardshipissuesimportanttopreservingandconservingfragileFirstAmericansculturalandnaturalresources;and(3)outlinetheneedforenhancedpubliceducationprogramstoinformtheworldabouttheimportanceofourhumanheritage.

ScholarlyFrontiers

Recentworldevents,particularlytheopeningofChinaandtheendoftheColdWar,makethisanopportunetimetoformulateaglobalvisionofFirstAmericansstudiesthatembracesAsia,NorthAmerica,andSouthAmerica.

DevelopmentofknowledgeaboutearlyAmericanhumanpopulationsisimportanttotheanthropologicalsubdisciplinesofsocioculturalanthropology,archaeology,linguistics,andphysicalandappliedanthropology.DataprovidedbyFirstAmericansresearchareessentialforthedevelopmentoftheoriestoexplainthemechanismsinvolvedinthedispersalofhumanpopulationsandvariationamongbiologicalpopulations,languages,andsocioculturalpatternsinferredfromthearchaeologicalrecord.TheyareimportanttoNativeAmericans'identificationofheritagevaluesforincorporationwithineducationandculturalmaintenanceprograms.FirstAmericansresearchprovidestheframeworkforunderstandinglaterperiodsofenvironmentaladaptationandculturaldevelopmentinAmericanprehistory,history,andcontemporarysociety.

Thefieldofearly-humanresearchintheNewWorldhascomeofage.FirstAmericansresearchdoesnotsimplycontributetoanthropologicalorhistoricalproblems;itprovidesprimarydataimportantforunderstandinglocal,regional,andglobalissuesrelevanttoexplainingthedynamicsandlinkagesamongpaleoclimatic,geologic,paleoecologic,andhumanadaptivesystemsandchangesintheselinkedsystemsthroughtime.

Page33

ArchaeologyandQuaternarySciences

Ratherthanadvocatingasingleperspectiveormodel,weoutlinephilosophicalconsiderationsimportanttodevelopingasystematicknowledgeofAmerica'searlyprehistory.Archaeologicalfieldresearch,whichproducestheprimaryscientificdataforreconstructingAmerica'searlyculturalheritage,hasbecomeincreasinglysophisticatedinusingamultidisciplinaryapproach.BydrawingupontheallieddisciplinesofarchaeologyandtheQuaternarysciences,researchersnowhaveamultiplicityofspecializedtoolsattheirdisposalforreconstructinghowpeoplelivedinpastenvironments,aswellasthemeansforinvestigatinghumanresponsetorapidlychangingenvironmentalcircumstances.

MuchnewinformationdocumentingregionalenvironmentalandarchaeologicalrecordsfromAsia,NorthAmerica,andSouthAmericaisnow,orsoonwillbe,available(Agenbroadetal.1990,BonnichsenandDillehayforthcoming,BonnichsenandSorg1989,BonnichsenandSteeleforthcoming,BonnichsenandTurnmire1991,Bonnichsenetal.forthcoming(a),Bonnichsenetal.forthcoming(b),Bryan1986,Carlisle1988,DillehayandMeltzer1991,Dillehayetal.1992,MeadandMeltzer1985,NunezandMeggers1987,StanfordandDay1991,TankersleyandIsaac1990).Despitethisgrowingvolumeofqualityinformation,ourunderstandingofearlyAmericanprehistoryremainsamazinglysketchyandeventhebestdefinedregionalpatternsarepoorlyknown.Forexample,theCloviscomplexoftheUnitedStateshasreceivedgreaterscientificattentionthananyotherearlyregionalpatterninthecountry,andpopularwritershavecharacterizedthispatternasproducedbyspear-wieldingmammothhunters.Yetwedonothaveafirmunderstandingof(1)theantecedentsofthispattern,(2)theorganizationaldynamicsofClovissocioculturalgroups,(3)thefactorsresponsibleforregionalvariationofflutedpointassemblages,

(4)whetherClovisrepresentsoneorseveralculturalgroups,or(5)whatledtothedemiseortransformationofthispatterntootherforms.

EarlyAmericanarchaeologicalcomplexesareusuallydistinguishedbyuniqueanddiagnosticprojectilepointstyles.

Page34

Thesestylesareassumedtohavebeenproducedby,andthustoarchaeologicallyidentify,differentsocioculturalgroupsofprehistoricpeople.SuchcomplexesincludetheNenanaofAlaskawithitslanceolateprojectilepoints(Goebeletal.1991),thePaleoarcticpatternwithwedge-shapedmicrobladecores(Clark1991),theGoshenwithitsconcave-basedlanceolatepoints(Frison1991),theWesternPluvialLakewithitslonglanceolatepoints(Bryan1991),theElJobowithitsbullet-shapedlanceolates(Bryan1991,Gruhn1991),andthefishtailpointcomplexwithitsstemmedflutedpoints(Politis1991).However,ourunderstandingoftheorganizationalanddistributionalvariabilityofthesevariouscomplexesispoor,asisourunderstandingofthesimplecoreandflaketoolpatternsofSouthAmerica(Bryan1991,Gruhn1991).ItshouldcomeasnosurprisethatrelationshipsamongregionalarchaeologicalrecordsareoftenambiguousandhavemitigatedagainstwidespreadacceptanceofgeneralmodelsofhumanmigrationwhichseektoexplainthepeoplingoftheAmericas.

SeveralimpedimentshavestoodinthewayofdevelopingasystematicknowledgeoftheFirstAmericans.Ithasbeendifficultforwidelydispersedresearchers,isolatedbylanguagebarriers,tobeawareofandtoassimilateresearchresultsfromoutsideoftheirownnations.Researchisoftenguidedbydissimilarstandardsandresultsareoftennotcomparablefromonereporttothenext.Availablefinancialresourcesareunevenlydistributedamongnations.Consequently,researchonthepeoplingoftheAmericashasdevelopedinanunevenandpiecemealfashion.

AbroaderperspectiveisneededtooffsetacommonbiasinPaleoindianresearchabiastowardviewingchronologiesandotherideasdevelopedintheU.S.SouthwestandGreatPlainsasappropriateasabasisforinterpretingrecordsfromotherareas.ScholarstraditionallyhaveapproachedthepeoplingoftheAmericasby

attemptingtoexplainlocalandregionalarchaeologicalrecords.Ratherthanextrapolatingresultsfromoneareatoanother,thecaseforAmerica'searliestculturalheritageshouldbedevelopedbyencouragingtheproductionofqualitysitereportsfrommanyareaswithdetaileddatapresentationthatdrawonthefullcomplementofallieddisciplines

Page35

embracedbytheQuaternarysciencesincludinganthropology.QualitysitereportsarevitalfordevelopingasystematicknowledgeofLatePleistocenearchaeologicalandenvironmentalrecordsfromAsia,SouthAmerica,andNorthAmerica.Thesedatacan,inturn,besynthesizedandusedforconstructingviablemodelsofearlyAmericanprehistory.

Abasicproblemwithearlyhumansresearchisthatitistoodependentuponinductiveinterpretation.Althoughthiscomplaintmayseemold,astrongargumentcanbemadeformoreproblem-orientedresearchthanthatdonebymostFirstAmericanscontributors.Thegoalofunderstandingtheorganizingprinciplesresponsibleformigration,colonization,adaptation,andpossiblelinkageswithnaturalenvironmentalchangesisafarmoredifficultandtime-consumingtypeofsciencethanisdevelopingaphasesequenceorexcavatingasinglesitepresumedtoberepresentativeofacultureorsubculture.Toviewacultureasamobileniche-fillingsystemcallsforarchaeologiststostructuretheirresearchwithinaproblemframework.

Well-formulatedhypothesesabout(1)thedynamicsgoverningtherise,operations,anddemiseofpastsocieties;(2)thecausesresponsibleformigrationandcolonization;and(3)linkagesbetweenenvironmentalandculturalchangesareneededtofocusandinvigoratethisfieldofinvestigation.Thiswillalsorequireafocusonspecific,usuallylocal,problemsorsetsofcloselyrelatedproblemsofsignificance.Becauseofthemultidisciplinarynatureofdataatarchaeologicalsites,eachofusmustbeawareofproblemsofconcerntootherscientistsandofthedatademandsofaddressingthoseproblems.Thedevelopmentofviablemultidisciplinaryresearchdesignsfordatarecoverymustbetemperedbythekindsofdatapresent,availabletimeandmoney,andthedesiretoobtainandreportrepresentativesamplesofalltypesofdatapresentatasite.And,ifpossible,thedatademandsofas-yet-undefinedfutureproblemsmust

beanticipated.

Anumberofneedsmustbemetinfulfillingthegoalofpreparingbettersitereportsanddevelopinghypothesesimportantforinterpretinglocal,regional,andglobalproblems.

Page36

1.Toevaluatetheappropriatenessofassumptionsemployedinmakinginferencesaboutspecificarchaeologicalsitesandthenaturalenvironmentsinwhichtheyoccurred.Forexample,itwouldbeusefultoevaluatetheappropriatenessofbasicassumptions,suchas:(1)therewasauniversalPaleoindianstage;(2)therewerevastmigrationsduringthePleistocene/Holocenetransition;and(3)theinitialpeoplingofBeringiarequiredanUpperPaleolithicleveloftechnology.

Intheprocessofdevelopinganaloguesforinterpretingthepast,wemustbekeenlyawarethatthedynamicsandlinkagesamongtheearth'soceanographic,atmospheric,climatic,glaciologic,geologic,andbioticsystemshavenotbeenconstantthroughtime(RuddimanandWright1987).Contemporarypaleoclimatologicalresearchsuggeststhatthelinkagesamongtheearth'senvironmentalsubsystemswerediscretelydifferentduringglacialandinterglacialtimes(BroekerandDenton1990a,1990b).Thetransitionfromglacialtointerglacialperiodsisthoughttohavebeenabruptandtohavebeensynchronousworld-wide.Theprecisemechanismsresponsiblefortransitionsbetweenglacialandinterglacialenvironmentalsystemsarenotfullyunderstoodandarebeingresearchedactively.

OfparticularimportancetothepeoplingoftheAmericasistheissueofhowhumansrespondtoabruptclimatechange.ThechangeatthePleistocene/Holoceneboundaryispostulatedtohavehadadramaticimpactontheworld'slandscapes.Theamountofavailableglacialicewassignificantlyreduced;sealevelsrose,drowningformershorelines;temperatureandprecipitationpatternschanged;theamountanddistributionofsurfacewaterwasgreatlyaltered;andthestructuresofplantandanimalcommunitiesweresignificantlymodified.AlthoughconsiderableeffortisbeingmadetounderstandthedynamicsofhowthelastIceAgeended,wealsoneedtounderstandhowglacialandinterstadialperiodsbeginandterminate.Therecanbelittledoubtthattheselinkedeventsdramaticallyaffected

thewayshumansrelatedtothenaturalenvironment.

Page37

ArchaeologicalresearchonhumanadaptationstoHoloceneenvironmentsprovidesuswithawealthofinformationonthearrayofadaptivepatternsdevisedinresponsetothemostrecentinterglacialenvironment.However,ourknowledgeofhumanadaptationstoglacialandinterstadialenvironmentsislimitedbyasparseandfragmentaryarchaeologicalrecord.

Welackmodernanaloguesforunderstandinghowhumansrespondedtoglobalenvironmentalchangesduringthetransitionsbetweenglacial,interglacial,andinterstadialperiods.AlogicalbeginningfocusforFirstAmericansresearchisonhumanresponsetoglobalclimaticchangeattheendofthelastIceAge.Fortunately,thelateAsiaticUpperPaleolithicandlateIceAgeAmericanarchaeologicalrecordsprovideunparalleledopportunitiestoexaminehumanresponsetoglobalenvironmentalchangeatopicofcontemporaryrelevance.

2.TointroducenewconceptsandanalytictechniquesmoreconsistentwiththecontentandstructureoftheLatePleistocenearchaeologicalsites.OneofthemajorweaknessesofFirstAmericansresearchistheminimalamountofsystematicsurveycarriedouttosearchforLatePleistocenesettlementandland-usepatterns.MostearlyhumanresearchinAsiaandtheAmericascanbecharacterizedasreactive,i.e.,wereacttothediscoveryofaninterestingsiteorartifactsratherthansystematicallyandproactivelysearchingforsuchsites.

AmajorthemeofFirstAmericansresearchshouldbetheinvestigationofvariables,bothenvironmentalanddemographic,thatmighthaveinfluencedhunter-gatherergroups'decisionsconcerningsiteplacementanduse,migration,andcolonization.ThearchaeologicalrecordpriortotheClovisperiod,beginningat11,500yearsBP,remainspainfullysparse.Westilldonothaveaclearunderstandingofwhythesegroupslocatedsiteswheretheydid,muchlesswheremoreearlysitesarelikelytobefound.Weneedtodevelopreliable

proceduresforisolatingdeterminantsofsitelocationusingempiricaldata.

3.Todevelopachronologicalframeworkofwell-datedarchaeologicalandassociatedenvironmentalremainsbasedonradiometricdates(Kra1988,1989a,1989b).ReneeKra'sInternationalRadiocarbonDataBaseisanimportantpioneereffort

Page38

tocompileexistingdataanduseastandardizedprotocolforevaluatingradiocarbondates.Thisworld-widecompilationofradiocarbondatescanbequeriedtoinvestigateavarietyoftopicsbygeographicalareaorbysubject.ItprovidesanimportantresearchtoolforinvestigatingQuaternarytopics,includingprehistoricarchaeologicalsitesandtheirenvironments.

Anadditionalbrightspotonthechronologicalfrontisthemethodologicaladvancerepresentedbyacceleratormassspectrometry(AMS).TheAMSmethodprovidesameansfordatingmuchsmallersamplesthanwaspreviouslypossiblewithconventional14Cmethods(Stafford1991;Taylor1991).Withthisnewtechnologywenowhaveasufficientlyprecisetechniquetotestnumeroustemporalhypothesesaboutmigration,colonization,andadaptationstopastenvironments.

4.TodeveloppaleoenvironmentaldatabasesfortheLatePleistoceneandHoloceneperiods.Theformulationoflocal,regional,andglobalhypothesesrelevanttoFirstAmericansstudiesrequiressynthesisandintegrationofinformationfromavarietyofdisciplines.Anincrediblewealthofnewinformationisnowavailable(RuddimanandWright1987).ComputertechnologycoupledwithdatabasesoftwareprovideameansforaccessingrelevantdatafromtheallieddisciplinesoftheQuaternarysciences.Theadvantagesofthedatabaseapproacharethatit(1)imposesstandardsinrecordingdata;(2)allowsbiasesinexistingdatatobeidentified;and(3)permitsmassivevolumesofdatatobeanalyzed,displayed,andintegrated.Electronicdatastorageprovidesthemeansfortestingawealthofhypothesesaboutculturalandenvironmentalrelationshipsonthelocal,regional,andglobalscales.

Inamajorongoingeffort,staffattheIllinoisStateMuseum,Springfield,aredevelopingpubliclyaccessibledatabasestoaccommodatepaleoecologicalinformation(WiantandGraham1987).Paradox,astandardrelationaldatabasesoftware,coupledwitha

GeographicalInformationSystem(GIS),accommodatesbothpaleobotanicalandfaunaldata.ApaleobotanicalDatabase-NorthAmericaandEuropeisbeingcompiledwiththeultimateobjectiveofreconstructingpaleoclimaticsystems.

Page39

Enteredvariablesincludegeology,14Cdates,sitelocation,andtreering,historic,andoceanographicdata.FaunMap,adatabasedevotedtovertebrateremainsfromNorthAmericaoverthelast40,000years,isapilotprojecttocompilesystematicallywhatisknownaboutlatePleistoceneandHolocenevertebratesinNorthAmerica.UsinganARC/INFOprogram,digitizedinformationcanbeplottedontomapssothatitispossibletoexaminethedistributionofspeciesbyindividualsorincommunitiesintimeseries.TheMineralsManagementServiceintheU.S.DepartmentoftheInteriorhasdevelopedacomputerized(indBASEIV)ArchaeologicalandShipwreckInformationSystemtoprovideinformationaboutsubmergedprehistoricsitesontheU.S.continentalshelfoffthecoastsofthelowerforty-eightstates.

5.Toinvestigatetherangeandnatureofarchaeologicalsitedata,withineacharea,thatwillelucidatethevariouskindsofbehavioral,organizational,andenvironmentalpatternspresent.TheArcheologicalSurveyofArkansas,withthesupportoftheU.S.ArmyCorpsofEngineers,hasdevelopedthedatabasesystemAutomaticManagerofArcheologicalSiteDatainArkansas(AMASDA).Thisdatabase,whichcoverstheNorthAmericanSouthernPlainseight-statearea,integrateswithGRASS,aGISrelationaldatabasedevelopedbytheCorpsofEngineers.Anumberofvariablesisincluded,suchasremotesensingdata,drainage,soils,geology,artificialboundaries,adaptationandbioarchaeologicaldata,andreportinformationaboutauthorandproject.AMASDAbibliographicalinformationisincludedwithintheNationalParkService'scomputerizedon-lineNationalArcheologicalDatabase(NADB)-Reportsofthegrey(i.e.,minimallyreproducedandavailable)literatureofU.S.archaeology(Canouts1991).Numerousreportsandoverlaymapscanbegeneratedbythisinnovativesystem.TheAMASDAsystemisnowbeingappliedtotheU.S.CentralandNorthernPlainsten-stateareabytheArmyCorpsofEngineers(Ewen

1993).Thissystemappearstobeideallysuitedforintegratingdatafromamuchlargerarea,andcouldbeadaptedtothetaskofintegratingculturalandenvironmentaldatafromAsia,NorthAmerica,andSouthAmericaimportanttounderstandingthepeoplingoftheAmericas.

Page40

6.Todevelopstandardizedclassificationanddescriptivetechniquesforreportingartifacts.Abriefglanceattheartifactsectionofmostsitereportswillattesttotheirscantandofteninadequatedescriptions.Thelackofuniversallyacceptedterminologyanddifferentstandardsforreportingartifactformaldimensions,technology,use-wear,andrawmaterialsusedinartifactproductionhavecreatedapersistentproblem.Poorlydevelopedlinedrawings,weaksupportingdescriptions,andcasual,inconsistent,andundescribedanalyticalproceduresareamongthemanyissuesthatnowdiminishthevalueofreportsandmakecomparisonsamongarchaeologicalassemblagesdifficult.Thesemethodologicalissuesmustbeaddressedifwearetoconductcrediblescienceandgeneratemeaningfulreconstructions.Asthingsnowstand,scholarswhoareseriouslyinterestedinFirstAmericansresearchmustexaminemostcollectionsfirst-handbytravelingtowherecollectionsarehoused.Thisapproachisextraordinarilyexpensive,time-consuming,andsubjective.

Morlan(1991)hasrecommendedtheestablishmentofaninternationalcommissiontodevelopauniformterminologyforarchaeologicalartifactdescription.Standardscanbemostreadilyachievedbytakingadvantageofnewadvancesinvideoandcomputertechnology.Itisnowpossibletostoreandmanipulateartifactimagesinthecomputer;variousimageenhancementandmorphometrictechniquesarenowavailableinsoftwarepackagesthatcanbeusedtoanalyzecomputerimagesofartifactsandtomeasuredimensionsandfeaturesofinterest.Theadvantageofavisualdigitalimagerysystemisthatartifactimagesfromimportantsitescanbestoredinadatabaseandelectronicallyreproducedforusebymanyinvestigators.AprototypeofthissystemisnowinoperationattheCSFA,anditappearstobeaviablesolutiontotheproblemofcomparingartifactsfromdistantpartsoftheworldingreaterdetailthanwaspreviouslypossible.Tomaximizethebenefitsofthisnewtechnology,thecommission's

mandateshouldalsoincludeadirectivetoformulatestandardsfordocumentingimages,developanetworktocollectimages,deviseaprotocoltoregulateaccesstodatabaseinformation,andcreateastandardizednomenclaturesystem.

Page41