The Promised Land

-

Upload

axis-graphic-design -

Category

Documents

-

view

238 -

download

4

description

Transcript of The Promised Land

N e v i l l e G a b i e

The Promised Land

HOUSE OF FRASER HARVEY NICHOLS CINEMA DELUX BRASSERIE BLANC A WEAR ALDO ALL SAINTS AMANO CAFÉ AMERICAN APPAREL APPLE @MOSS BANK BARRATTS BENCH BLOOMSBURY BURTON CAFÉ ROUGE CARLUCCIOS CARPHONE WAREHOUSE CLAIRE’S COAL CHANDOS DELI CAFÉ CREW CRUISE CRYSTAL RIVERS CULT DWELL DOROTHY PERKINS ELLISS & KILLPATRICK ERNEST JONES ESPRIT EXPLORE LEARNING FAT FACE FOSSIL FRANKIE & BENNY’S FRASER HART FRED PERRY FRENCH CONNECTION G STAR GAME GERRY WEBER GHOST GIRAFFE GOURMET BURGER KITCHEN GOLDSMITHS GUESS GUESS ACCESSORIES H SAMUEL H & M HARVEY NICHOLS HARDY AMIES HENLEYS HOBBS HOLLAND & BARRETT HSBC HUGO BOSS ID EST BRISTOL

JANE NORMAN JD SPORTS JJB SPORTS KURT GEIGER LA SENZA LA TASCA LACOSTE LINKS OF LONDON LK BENNETT LOMBOK MILLIE’S COOKIES MOLTON BROWN MONSOON ACCESSORIZE NANDOS NATIONWIDE NEW LOOK NEW CUTSNEXT OAKLEY OASIS OLLIE & NICPATISSERIE VALERIE PICCOLINO PRAVINS PRET A MANGER PRINCIPLES PUMA RADLEY REISS REPUBLIC RIVER ISLAND SCHUH SHAKEABOUT SOHO CAFÉ SONY CENTRE STARBUCKS SWAROVSKI TAMPOPO TED BAKER THE BODY SHOP THE ENTERTAINER THE PERFUME SHOP THE WHITE COMPANY THOMAS SABO THOMAS PINK TM LEWIN 3 STORE TRANSFORM YOUR IMAGES URBAN OUTFITTERS VODAFONE WALLIS WAREHOUSE ZARA ZAVVI ZIZZI YO SUSHI TOPSHOP / TOPMAN THOUGHTS COSTA HOTEL CHOCOLAT

The first shrines had begun to appear, wayside altars for passing shoppers,

places of pause and reflection for those making endless journeys within the

universe of the dome.

J. G. Ballard, Kingdom Come. First published in 2006 by Fourth Estate.

The secrets of human existence

‘What exactly does an artist in residence do on a huge building site for three years?’

Neville Gabie poses this question in the first lines of his Introduction to Canteen – A

Building Site Cookbook. The vinyl-coated volume provides over 60 recipes from all over

the world and is illustrated with brightly coloured images of food, ingredients, chefs,

kitchens, queues and diners. Hard hats and high-visibility jackets are ubiquitous but the

faces and hands are symbolic of the 59 nationalities which were represented on site –

the Cabot Circus building site.

From mid-2006 until the end of 2008 Neville Gabie worked within the context of this

37-acre building site in the centre of Bristol. As an artist, amongst surveyors, architects,

engineers, contractors, sub-contractors, concreters and representatives of many other

trades, he made permanent as well as temporary work. ‘Work’ is a general enough

term to sum up all his activity and yet says nothing of its motivation, impetus, form or

meaning. His practice, as we would say in the art world, has for many years centred

on working responsively to specific locations or situations and Cabot Circus was no

exception. The Cookbook documents elements of a work – a project which Gabie

devised by asking site workers to submit favourite recipes. Over a period of months

these were translated, selected, duly prepared by chefs from local restaurants, and

then served back to groups of workers on the site. Gabie had identified early on in his

residency that meal breaks provided the only brief moments of social activity within the

long working day. Feeling that food defines our cultural heritage, he saw these meals

as a way of involving people who made up the large temporary and often itinerant

workforce around him. In his diary-like blog he captures something of these meals as

events as well as logistical challenges:

Sunday 4 May 2008 – Held in the car park site the Braai was planned to coincide

with the last concrete pour as a moment of celebration. We made the meal

open to all and cooked for 120 people. When the queues began to assemble on

the sixth floor of the car park I began to panic but it was a fantastic afternoon.

The Braai included two whole spit roast lambs, Boerewors, Mielle Tarts, roast

potatoes and Durban Banana curry salad. Not only was the meal great but

the preparations were spectacular too and it began by taking all the cooking

equipment up to the sixth floor using a skip and the site crane.

This work, for which the Cookbook is an appropriately stylish but practical document,

says so much about Neville Gabie as an artist. He has always been drawn to place and

human responses to location. From the outset, as a student at the Royal College of Art

(1986–88) he began making work on a site off the Finchley Road which was used for

dumping rubbish. By day it was used by fly-tippers leaving domestic detritus, by night it

was occupied by tramps, who used the discarded household objects to create temporary

homes for themselves. Gabie even then was interested in how spaces became potent

and politicised, changed by their users and occupants. In 1995/96, returning to his native

South Africa as part of an artist exchange, he made a series of works which reflected on

how those forced to be itinerant take all their possessions, their homes, with them. This

more recent recipe project has close parallels in how he identified a way of expressing a

site through its workforce, and through the cultures they bring with them.

Neville Gabie’s skill lies in how he uses opportunities to make work. As Artist in

Residence, appointed by InSite Arts on behalf of Bristol Alliance, he was commissioned

but, unusually, given no specific brief. (Separately, InSite Arts was developing a public art

programme which would produce a series of permanent works by other artists.) So Gabie

was free to respond to Cabot Circus as a place – its context and meaning. Having always

been interested in responding to such contexts beyond the studio, his preoccupation

was likely to centre upon establishing a relationship to this particular environment and

to consider its physical, cultural and emotional significance. As Lewis Mumford, urban

historian, sociologist and architectural critic, noted, ‘The city as a purely physical fact has

been subject to numerous investigations. But what is the city as a social institution?’1

Gabie is unusual in how he often involves people in the making of his work. He works

collaboratively, whether with other artists or, as in this instance, site workers. In fact,

realising that Cabot Circus in both physical size and number of workers (over 2,000) was

almost too large and complex, he quickly identified that it offered huge potential to other

artists beyond himself. ‘As one voice I could not do justice to what was here, nor did I

feel I could ignore aspects of the development which ought to be considered.’2 Applying

for additional funds from Arts Council England, together with Sam Wilkinson of InSite

Arts, he facilitated and invited a further eight artists to become involved. This project

became known as BS1. Thus this way of working, generously identifying and sharing

opportunities, is part of his artistic practice. In Liverpool he had done something similar.

From a Momart Residency at Tate Gallery Liverpool in 1999/2000, he had developed

what was to become a four-year project with other artists. Starting out by occupying

a flat on his own in Kenley Close, a 1960s’ tower block in Sheil Park north of the city,

he then, together with artists Leo Fitzmaurice and Kelly Large, proceeded to invite ten

further artists to live in other surrounding flats for six weeks. The block was destined for

demolition in what is now a familiar prophetic cycle of renewal. Sheil Park had originally

been a ‘new town’ development, a solution to poor living conditions symbolised by

run-down Victorian terraces. Optimism of the post-war era envisaged mod cons for

everyone. The sites for this type of modern living had now themselves become a byword

for all that was bad. The residents were once again to be moved and rehoused.

For Neville Gabie this context raised a series of questions – how did it feel to be a

resident who was about to go through such change; to watch personal memories

be destroyed; to never again have the dramatic high-rise views; to be resettled but

dislocated from all that one knew and felt familiar with? His project Up In The Air led

to Further Up in the Air, which again he developed with Leo Fitzmaurice, where 18

nationally and internationally known artists and writers occupied a neighbouring block,

Linosa Close, over a two-year period. Kenley had by this time been demolished and the

community of Linosa was preparing to leave. The personality of an artist always comes

out in his work and for Neville Gabie it is his interest in people and his innate humanity

which surfaces. Once again taking away the focus on bricks and mortar, he befriended

Linosa Close’s caretakers, Chris and Colin, and built relationships with residents as well

as with his creative visitors. The Chair of the Liverpool Housing Action Trust supported

the initiative, later commenting: ‘Much of it is the sort of work that many people would

consider “difficult”, but not the remaining tenants and the surrounding community who

welcomed the artists, worked with them and then adopted the roles of curators and

invigilators, explaining and guiding the numerous visitors round the block with their usual

proprietorial and cheerful manner. The work was varied and thought provoking, centred

as it was on the nature of the community in which it was based.’3

Further Up in the Air enabled artists to develop their work freely, creating extraordinary

memorials to this once lively social hub and its new regeneration context. As Paul Kelly of

the LHAT commented at the time, ‘From a community development perspective a new

way of involving artists within community settings has emerged.’4

Although trained as a sculptor, Neville Gabie has never focused purely upon the object

but upon the object’s associations, its links to human activity, to human narratives. He

admits the sites he decides to work with ‘are not arbitrary or randomly selected, but

fit together, being places in a state of physical or social flux. The nature of locations

I choose to work in demands flexibility. Working in a range of media from sculpture

to film and photography, projects are usually developed over a sustained period of

involvement…’ His work physically fits no particular description but the contexts he

decides to place himself in perhaps do. As Martha Rosler has commented ‘Consider

the city once again. It is more than a set of relationships and a congeries of buildings,

it is even more than a geopolitical locale – it is a set of unfolding historical processes.’5

It is these processes that Gabie over the years has immersed himself in. He finds

himself offered and applying for commissions and residencies within so-called public art

contexts. These have enabled him to work in ways that suit but also come with a host

of other associations and rationales. Traditionally, art in the public realm has been placed

or introduced for ‘reasons of aesthetic enhancement, memorialisation or simply because

introducing art into everyday life has been seen as an inherently good thing. However

since the early 1980s public art has been advocated as contributing to the alleviation of

a range of environmental, social and economic problems locating it squarely within the

process of regeneration. Since the 1980s public art has been increasingly implicated

in processes such as the rejuvenation of decaying urban spaces, the development of

flagship projects of urban regeneration, the stimulation of central city economies and

the enhancement or transformation of urban images.’6 Neville Gabie is ambivalent about

being associated with such motivation and re-imaging. ‘I’ve got nothing against the grand

gesture which is so prevalent in contemporary art… But for me the life and death things,

the real big issues, are to be seen equally in the mundane, the ordinary, the everyday

experience. You don’t need the big gesture. And, anyway, the big gesture can undermine

the real meaning.’7 Much of his work is about making meaningful projects, where

process as much as the resultant work gives or leaves impact. His series of thoughtful

publications, created in partnership with designer Alan Ward, are often the only physical

trace of his working practice, yet people’s experience and memories of the live activity

will endure.

In this he has been affected by how little critical writing or evaluation of the ‘art’

produced by public art programmes there is, other than that provided by its advocates

and promoters. An artist is positioned by his or her style of practice, and in Neville

Gabie’s case his practice often positions him outside the usual critical frameworks of

galleries and museums, whether public or commercial. Artists who are flexible and

pursue less conventional ways of making art have found it hard to both set out their

rationale and then achieve a process of validation for their work. This is particularly

curious when the practice is linked to involving people in this self-professed age of

developing audiences. As the urban geographer Tim Hall has noted, there has been little

discussion of who the audiences of public art are, and even less discussion as to what

their actual experience of the art is.

So Neville Gabie’s projects are a creative mix of the temporary, which gives rise to

tangible experience, and the more permanent, which becomes a lasting testament to

something specific in society. Several further works at Cabot Circus provide potent

examples. Cabot Circus Cantata, still being performed, is a moving musical description of

how today’s society is culturally diverse and the labour market constantly on the move.

This work is once again collaborative in nature, from the site workforce being cajoled

into singing songs, through to composer and conductor David Ogden together with the

City of Bristol Choir transcribing and singing a selection of fifteen of them. The idea

came to Gabie when he heard someone singing as they worked. He realised they were

not alone in doing this; different languages, different songs were being performed daily

across the building site. ‘Hearing a tiny single voice in the midst of this chaos made me

stop.’8 The performances, in the shell of one of the recently completed buildings, again

in nearby St James Priory and by loudspeaker as a concert for those working on site,

were made more poignant by the active participation of some of the original contributors.

Raymond Henry, a banksman, Santokh Singh, a concrete labourer, and one or two others

performed their own selected songs. To see robust builders, full of emotion for the

homes and countries they miss, is both memorable but also evidence of what the current

labour market does to society. As the artist simply states, ‘These moments of exchange

were the essence of the project.’9

Another project, which might appear more physically conventional, is that of A weight

of stone carried from China for you. It takes the form of a 150 kg granite kerbstone, now

sited on Penn Street within the Cabot Circus development. The work’s title literally

describes its provenance. Gabie researched and then travelled to where all of the sites’s

kerbstones were to be quarried and cut. His intervention was to have carved the location,

quarry, date and stone type in Mandarin along its length. He then proceeded to bring the

stone back to Bristol by hand truck. His perseverance with projects is well known but this

excerpt from his blog provides a vivid description:

Saturday 30 June 2007 – To my great surprise the two drivers who brought me

from Xiamen also came to help me onto the train. I had no idea how much I would

need their help. We arrived at Beijing railway station in the pouring rain and I was

in for a shock. The station was packed, the noise was immense and there was not

a single sign I could read. Mr Xue, all 5ft4” of him, but as strong as an ox, pushed

the stone on its trolley into the station, up escalators, along corridors, down

stairways through crowds of people and eventually manhandled it onto the train.

The trolley was worse for the experience, but without him to move the stone and

Sarah to find out where to go, I think I would have ended up in Beijing forever.

When the train finally rolled out of the station I was an emotional wreck. Foolishly

I thought things would now be plain sailing for six days and six nights to Moscow,

but I could not have been more wrong.

The title of the work sums up so much: ‘…for you’ expresses simply Gabie’s approach.

His works relate to people whether they are part of the making or not. In the final stages

of Further Up in the Air, he and Leo Fitzmaurice compiled a book of artists’ proposals in

order to reveal each contributor’s thinking processes. Gabie’s involved flying kites with

cameras – he wished to reunite residents with their former views across the city. Here

at Cabot Circus he wanted to reunite future users of the shopping centre with the people

and processes of its making. Many of his works take time to validate the present and the

past while looking forward to a fresh future.

100% Ford Mondeo is another more permanent memorial to the creation of Cabot

Circus. Buying a car from a Bristol resident on eBay, Gabie had it melted down to provide

reinforcing bars for one and a half columns in the centre’s new car park. Intrigued and a

little surprised by the level of positive commitment to recycling that he found with some

of the site’s biggest construction companies, Gabie expresses in this work something of

where our society is at with wanting to achieve a more sustainable future. Once again his

blog enables us to experience the process of making the work:

Saturday 25 August 2007 – The 680 kgs of Ford Mondeo arrived at Celsa in

Cardiff on the back of a skip truck. The next stage is melting the car down and

casting the steel into billets. My first worry was how to track the Ford through

the whole process, but in fact it was very easy. As soon as the metal from the

car was lifted into the cast pot it is given a cast number which will stay with this

batch of steel forever. The whole plant in Cardiff is sophisticatedly computerised

with every bit of steel tracked throughout the whole process. What an amazing

place! Dressed in heavy [and very hot] woollen fire retardant clothing, earplugs,

boots and helmet, I went into the plant. Even with the earplugs the noise, smoke

and flames are overwhelming. We tracked the car being melted and cast into steel

billets. From here the billets will be taken to the rod-mill.

100% Ford Mondeo can be seen on the third and fourth floors of the car park and

answers the question Patricia Phillips posed in her now well known essay Out of Order:

The Public Art Machine:10 ‘What is it that public art can uniquely do?’ Phillips felt that

the notion of ‘public’ was not only a special construct but the very nature of ‘publicness’

came not merely from location but from the nature of engagement. Neville Gabie goes

so far as to admit that he doesn’t really understand the term ‘public art’ and how it is

used. He feels his work is always a journey, reflecting the communities it is part of. Like

Phillips, he sees art as an investigation, a social discussion of the experiences of many,

not just the artist. He has for many years returned to taking photographs of the makeshift

goalposts different communities create in order to knock a ball about. He admits, ‘You

see… it’s not just the taking of the photos of the goalposts. In some ways they are just

an excuse to wander aimlessly around cities, exploring their undersides, the hidden bits,

the streets waiting to be demolished, the secrets of human existence.’11

Tessa Jackson

Notes

1 Lewis Mumford, ‘What is a City?’, Architectural Record, LXXXII (1937), n. p.2 Neville Gabie, BS1, InSite Arts, 2009, p. 5. 3 Paula Ridley in Further Up in the Air, Further A Field, 2003, p. 158.. 4 Paul Kelly in Further Up in the Air, p. 158. 5 Martha Rosler, ‘Fragments of a Metropolitan Viewpoint’, in If You Lived Here… The City in Art, Theory and Social Activism, ed. Martha Rosler and Brian Wallis, New Press, 1991, pp. 31–40. Also quoted in The City Cultures Reader, ed. Malcolm Miles and Tim Hall, with Iain Borden, Routledge, 2003, p. 119.6 Tim Hall, ‘Opening Up Public Art’s Spaces: Art, Regeneration and Audience’, in Cultures and Settlements, Intellect Books, 2003, also quoted in The City Cultures Reader, ed. Miles and Hall, p. 110.7 Neville Gabie, quoted in Bill Drummond, ‘Bill Shankly Was Wrong’, in Neville Gabie, Playing Away UK, Oriel Mostyn, 2004, n. p. 8 Neville Gabie, Cabot Circus Cantata, InSite Arts, 2008, n. p. 9 Gabie, Cabot Circus Cantata. 10 Patricia Phillips, Out of Order: The Public Art Machine, Artforum, 1989.11 Gabie, quoted in Drummond, ‘Bill Shankly Was Wrong’, in Gabie, Playing Away UK, n. p.

Tessa Jackson has worked in key positions within the British cultural sector, as a curator and gallery director and as a senior cultural policy-maker. Since 2002 Tessa has divided her time between running her own consultancy, International Cultural Development, and her role as founding Artistic Director/Chief Executive of Artes Mundi, Wales’ International Visual Art Prize. She is currently Acting Chief Executive of Iniva (Institute of International Visual Arts).

Where is the public in public art?

The pioneering work of Neville Gabie

Art is everywhere and has always been everywhere, for thousands of years. But in 2009

it could be argued that art has never had such global currency as it does today. There are

more artists than ever before, more studio blocks, creative clusters and quarters, more

higher education degrees in art, museums and galleries are springing up everywhere, the

art market has been booming (at least until recently), while the explosion in international

biennale culture on every continent since the early 1990s has been astonishing to

witness. Equally, public interest in art and artists, particularly among younger people, has

never been more acute. Art is popular everywhere.

Interest in art, and especially in contemporary art, is at an all-time high, with people

of all backgrounds visiting museums and galleries in record numbers (in the UK, more

people now go to museums and galleries than go to football matches). Tate Modern is

celebrated as the most popular museum of modern and contemporary art in the world,

with over five million visitors – many of them under the age of 30 – recorded each year,

while many more millions visit Tate online. Interestingly, recent reports suggest that,

despite the current economic slump, attendance figures at museums and galleries, and

at theatres and classical concerts, are so far holding up rather than collapsing. Does art

become more important, more vital, during times of economic hardship and recession?

But of course people are not just ‘visitors’ or ‘audience members’, to be passively fed

products or cultural content. Increasingly, they are also active agents in the world of

art. They want to participate. As well as witnessing and consuming the arts, people

are simultaneously doing it for themselves, enthusiastically embracing ever more

cheaply available technologies, actively creating their own art on many platforms and

then distributing their individually or collaboratively fashioned products and ideas,

often freely but sometimes as socially networked microbusiness operations, across

the globe in milliseconds. These are very exciting times. Compared to twenty or even

ten years ago, the British cultural and creative landscape has shifted so much that it is

almost unrecognisable, leading Sir Nicholas Serota, Director of Tate and one of our most

astute champions of contemporary culture, to declare that the country not only looks

different but it ‘feels’ different too. A further example of the UK’s recent cultural and

creative renaissance lies in the remarkable flourishing of the creative industries, which

consistently show one of the highest rates of growth year on year, of any sector within

the British economy.

In the UK today public art too has become something of an industry. Public art is

everywhere. We have witnessed over the last generation the proliferation of artists

who now call themselves ‘public artists’, college and university courses specialising in

public art, public art commissioning agencies, public art magazines and websites and

thinktanks, and, most dramatically of all, the widespread production of public art across

the nation. Public art is now a multi-million-pound business. Most urban communities

in the UK, and many rural communities too, have some form of public art in their public

realm – it is almost an expected aspect of contemporary development. Some of this

public art is average at best and some of it very good indeed. The best-known public

artwork in the UK today, and perhaps the most loved, is Antony Gormley’s The Angel

of the North in Gateshead, which captured the popular imagination soon after it was

unveiled in 1998. The fact that Google alone returns nearly 16 million matches for The

Angel of the North attests to the enormous and unprecedented interest this large and

iconic sculpture has created in the last eleven years.

My key question here is: where is the public in public art?

Many would suggest that the public has very little to do with public art – that much

public art, even today, is art that is imposed top-down upon the public without their

involvement or consent. (The common joke is that it is the kind of art that arrives on a

lorry in the middle of the night, only to be discovered at daybreak by the people who

have no choice but to live with it from then on.) Other commentators argue that much

public art is less important than gallery art and is merely the facile decoration, tidying

up or prettification of public or commercial spaces or, worse still, a cynical means by

which developers gain planning permissions more easily. Many also suggest that the

widespread professionalisation of public art has in many cases served only to distance

people further from the complex processes of commissioning and producing works

intended to stimulate, inform and animate our understanding and enjoyment of the public

realm. If this is the case, does such art in fact deserve the name of public art?

It is hard not to appreciate the irony of this situation. Much public art, alongside

community art, emerged precisely as a reaction against the perceived elitism,

impenetrability and complacency of the conventional gallery system, sparked by artists’

desire not to be contained or restricted by the requirements and the culture of the ‘white

cube’ and by the desire of cultural practitioners to extend the reach of art into everyday

life, into the streets and civic buildings, into the public realm, accessible to all.

This urge to broaden the reach of the arts is stronger today in the UK than it has ever

been. I’m interested in art for the many and not for the few, but also in art by the many

and not by the few. It is my passionate belief that, in this era of burgeoning everyday

rather than expert creativity, of accelerating mass collaboration in cultural production,

of co-creation in space- and city-making and of the increasing co-imagination and co-

design of our public services, artists, creative practitioners and cultural institutions will

need to shift urgently from outmoded, top-down twentieth-century (or even nineteenth-

century) ways of thinking and doing in order to create richer, deeper, longer-term, more

sophisticated, more productive, more plural and more playful and joyful relationships

with communities of all kinds; relationships that resist the impositions and patronising

one-way conversations of the past and instead foreground partnership, contestation,

negotiation and genuine dialogue in the making of art and public space of the very

highest quality. Change is irresistible. Those working in the arts can no longer inhabit a

bubble of complacent thinking or put up defences against the pressures from the mass.

New connections now need to be made between professional and amateur, expert and

lay, novice and veteran and, crucially, between the so-called margins and the centre and

between the local and the global – creating what the Scandinavians call the ‘glocal’ – if

we are truly to realise the enormous power of art, culture and creativity to transform our

lives and our communities. The encouraging thing is that publics of all kinds are hungry,

as never before, to be more closely involved in the making of the spaces that surround

them and that in some sense control their lives.

As an outstanding example of this urgently needed new approach to art-making and

close public involvement and collaboration we should look to the inspiring work of

Neville Gabie and particularly his innovative projects in Bristol during the development of

Cabot Circus.

Public art was envisaged as being integral to this ambitious scheme from its inception

and artists were commissioned to create new site-specific work responding to the

spaces being created, the history of the site and of Bristol, and the social and economic

context of the development, in order to create a lasting relationship between the works

and their location within the public realm, the site as a whole and the wider community.

Public art is generally assumed to be work that will have a long-term presence,

joining the plethora of statues, monuments and memorials in our communities whose

provenance stretches back over many centuries. But arguably some of the most

interesting and impactful public art today, including much of Neville’s work, is more

ephemeral, created with no intention of permanence.

Neville was appointed artist in residence at Cabot Circus in 2006. Most unusually, the

community he was charged to engage over the following 30 months of construction

consisted of the people working on the building site itself, people who would normally

be disregarded or ignored when it comes to art commissioning. As a child at school

I was taught that Sir Christopher Wren built St Paul’s Cathedral – which would have

been a staggering, practically superhuman achievement had it been true. But, of

course, the cathedral was actually built by a generation of craftsmen and labourers of

all kinds, the majority of whom are nameless, unknown and lost to history. In involving

the construction workers from the very beginning Neville demonstrated once again the

unshakeable generosity, curiosity about people and fierce democratic spirit that runs as a

seam through all of his work.

At any one time there were around four thousand workers on site, with many different

areas of expertise, professions and backgrounds. Over the whole construction period

more than twenty thousand people worked at Cabot Circus, making the site a mini-

city in its own right, focused on the remaking and refashioning of a larger city. Even

more remarkable was the fact that there were 59 different nationalities represented

within the workforce, with workers drawn from every continent, reflecting not only the

extraordinary diversity of the UK today – London now being the most diverse city in the

world, with over 300 languages spoken every day by London schoolchildren – but also

the global nature of the contemporary construction industry.

This rich context of diversity and global connection soon became the theme of Neville’s

residency, as he stated: ‘Bristol is a city with international connections – and this has

become even more evident with a development of this scale. Cabot Circus highlights

how much we rely on a global community, but it also highlights the responsibility we

have to the rest of the world. Something that should not be taken for granted.’

Neville spent time on site initially observing, documenting what was going on through

photography and film, trying to make sense of the incredibly complex processes at play,

finding his way around the labyrinth of the site, setting up his studio on site and, most

importantly of all, slowly and gently introducing himself to the workforce, which took

time given the high-pressure nature of the construction site – who would want someone

as irrelevant as an artist holding them up when there is a proper job to be done?

But over time Neville’s presence became accepted, not least due to his consistent

charm, modesty, generosity and above all his curiosity about other people and the lives

they have to lead. People on site were also curious about him and his unconventional

role. As a result, exchanges and conversations became richer and more regular. As he

developed a better understanding of what was happening on site Neville noticed that,

as people worked, they also often sang songs, some bawdy, others melancholy. This

led to the artwork Cabot Circus Cantata. Neville talked to people about their songs and

ultimately teamed up with the composer David Ogden to record songs from across

the site from security guards, concreters, secretaries, canteen staff, electricians and

foremen, most often not in English but rather in their own languages. David Ogden

reflected, ‘Many of the songs sung by the workers came from the heart. They are

reminders of their homeland, of their families and friends back home and so were sung

with great feeling and nostalgia.’ In the next stage of the project Neville and David

linked up with the renowned City of Bristol Choir, who went on to perform Cabot Circus

Cantata, a specially composed musical score developed from 25 of the workers’ songs.

The first performance of Cantata was on the construction site for the workers before

performances were given around the city. A beautiful book and DVD were then created

and released.

In the subsequent Canteen project, Neville encouraged site workers to contribute

recipes from their homelands, which were then transcribed and the meals cooked on

site in enormous and joyful banquets for the workers. The recipes and the feasts were

subsequently documented and brought together in a unique cookery book. What I glean

from Neville’s work in Bristol, and especially from these two projects, is a sense not

only of the huge rewards to be gained from bringing artists and communities into much

closer connection, but also of the extraordinary, yet still largely untapped, resource that

communities of all kinds represent as true partners in the creation of art – again of all kinds.

People are essential components of Neville’s work: they are collaborators, they inspire

and intrigue and surprise, and for Neville their cultures and their achievements, grand or

modest, are to be acknowledged and celebrated rather than ignored. People are in some

senses the material with which Neville fashions his purposeful art. This process is never

easy or straightforward. The long-term building and maintaining of relationships with a

large number of people, who start out as strangers, from initially unfamiliar backgrounds

and speaking different languages, requires a particular set of skills and understanding

from an artist – and Neville has clearly honed his immeasurable skills with people to

deliver his consistently successful outcomes.

Is Neville’s work public art? In the end I wonder whether this question matters.

The cultural and corporate sectors are only at the foothills of understanding the potential

of collaboration with the communities they normally define as their ‘audiences’ or

‘customers’, but I’m certain that much greater collaboration, co-design and cooperation

is the only possible choice. I look forward to a surprising, rewarding and hopefully slightly

dangerous twenty-first-century journey ahead for us all. And I am convinced that Neville

Gabie will continue to be at the forefront of this movement to connect – or to reconnect –

art, artists and communities in warm, generous and sophisticated ways that shift hearts

and minds.

Peter Jenkinson

Born in Essex of English and Irish heritage, Peter Jenkinson has worked for over 20 years in the cultural sector, passionately advocating and acting for deep and lasting change across the cultural and political landscape. In his current role as an independent cultural broker he works across a diverse portfolio of disciplines and sectors including broadcasting, public policy, regeneration, arts, creative industries and leadership development. Prior to this Peter has had a distinguished and award-winning career working across the arts and culture, including his role as founding director of the Creative Partnerships programme and the initiation and delivery of the world-class £21 million New Art Gallery Walsall. His key areas of interest include the critical roles of creativity, innovation, diversity and broader cultural literacy across society as well as a commitment to building social justice and intelligent democracy.

A weight of stone carried from China for you

Imagine a journey to fetch a single granite kerbstone from China, bringing it back

to Bristol overland by truck, train and ferry. Think of it being hacked from a

mountaintop boulder, cut into a neat rectangular block, strapped to a sack-truck

and pushed towards England.

The granite kerbstones used in the redevelopment of Cabot Circus came from

one quarry in Fujian Province, South East China. To consider the network of

people, process, distance and sustainability involved in supplying even the most

mundane parts of the jigsaw, making the journey between quarry and Penn Street

with one stone seemed essential. Tracing the long distance via Xiamen, Beijing,

Mongolia, Siberia, Moscow, Belorussia, Warsaw, Cologne, Calais, and Dover

created an opportunity to consider the web of links generated through trade. Now

the kerbstone, 90 × 20 × 30 cm, weighing roughly 150 kg and identical to the

surrounding stones in all respects apart from a simple text, lies in the

street in Broadmead.

Imagine for a moment you are standing on a mountaintop in China.

Imagine the smell of the plants and the noise of insects in sub-tropical heat.

Quarryn 24-40-111 e117-50-403

28th June 8am – Xiamen n 24-28-792 e118-04-70512.20Pm service station n26-14-925 e119-32-7196.30Pm service station n28-52-805 e121-13-41311.05Pm service station n31-12-547 e120-40-399

29th June 5.45am service station n35-10-214 e118-14-7328.45am Service station n36-56-850 e116-41.69811.20am service station n38-14-321 e116-43-785

30th June Beijing railway station

1st July 12.10pm Changchun n43-54-582 e125-19-103

3rd July10.10am Ulan-Ude n51-50-492 e107-34-8836.10pm Irkutsk n52-16-903 e104-15-667 10.30pm Zima n53-53 e102-02

4th July 11.30am Krasnoyarsk n56-00-451 e092-49-9236.10pm mariinsk n56-12-703 e087-44-590

2nd July4.05am manzhouli n49-34-989 e 117-26-572 n49-34-989 e 117-26-5725.03pm Borzya n50-23-388 e 116-31-110

9th July 6.30am Cologne n50-56-542 e006-57-455 5.45pm Calais n50-57-185 e001-46-506 9.45pm Dover n51-07-570 e001-19-591

6th July 8.30pm moscow n55-47-437 e037-44-883 moscow – ‘I wIll take the tone for a walk.’

8th July 5.20pm warsaw n52-15-086 e021-03-098

Bristol N 51-27-492 W 002-35-205

100% Ford Mondeo

Imagine a car supporting a building. A car used to build a car park.

A car purchased from Paul on eBay, then driven from his home in Bristol to a scrap-

yard in Newport. Stripped down, de-polluted and shredded into 680 kg of ‘frag’

before being transported to Celsa Steelworks in Cardiff. Tracked carefully through

fire as molten steel, through cooling, reheating and the roll-mill before finally

emerging as 32 mm re-bar. After a 114-mile round trip the Ford Mondeo R310

RCF returned to Bristol, now as reinforced steel, enough to support one and a half

concrete columns in a new multi-storey car park.

Sometimes it can be the most informal of conversations that influences a work –

in this instance a conversation on-site with a steel erector who casually mentioned

that all the steel being used to build the car park at Cabot Circus was recycled.

BS1 – NY10016 – BS1A PROPOSAL

Imagine digging a hole in New York to find a piece of Bristol.

Geoff The Stapleton Road itself was still quite a good shopping area but then of course you came up through West Street, Old Market and Castle Street and I just remember Castle Street which was a very busy area. The shops opened late on a Saturday evening and the whole place would be buzzing on Saturday till quite late with everyone in to do their shopping… Everything was there…

Then I can remember the night of the really big raid when Castle Street and all of this area was demolished… Beyond that there was this huge red glow and flames. You could still see quite clearly the fires in the Castle Street area.

Pat There was three terraces originally. We were Upper and there was Middle and Lower Terrace but Lower completely went in the bombing.

Jean …and the original tree, that is there…

Pat The only one – we used to play in it as kids…

Jean …and we scattered mum’s ashes around there because she was born there as well.

Pat Yes, mum was born there and Jean was but I wasn’t.

Jean That was our playground…

Leslie I always remember all these places, Castle Street and everything like that, especially on a Saturday night with all the barrow boys all up through in the gutter and all the shops and as there was no refrigeration in them days and the butcher shops and things like that, they would stand outside and offer you so and so for so many pence and all that because they had nowhere to store it. Of course we were kiddies then and we would wander about quite a lot around here. I also went to school in Castle Street. In Castle Green School. It was separated then, boys and girls, and the boys’ entrance was off Castle Street… I was called up in ’39 straight away when the war broke out…

Margaret …they had to buy Christmas presents for the family and all that. And they bought all their Christmas presents, left them in the store and didn’t want to take them home… and the store was bombed. It was bombed the night that they left all their Christmas presents in there. Lost all their coupons and everything…

Terry Everything was bombed from Masons’ [printing works] up to the top of Union Street… We weren’t very old but from our houses you could look straight over town, you could look all the way down here. We weren’t very old but in my mind we was all looking down there as Bristol was being bombed – Broadmead – all down that area was just all flames and the sky was red as anything and it just sticks in your mind, that particular night does.

Pete [Bristol City Council] But it is all this stuff – this photograph here in 1940 of Castle Street… I mean all that rubble has to go somewhere. But who is going to do it and how do they clear it?

Neville I know it’s a fanciful idea but I do like the idea of excavating a street in New York to reveal the history of another city, Bristol, on the other side of the world. Somehow this material dislocation seems so closely to reflect the huge shifts in population which perhaps began in the early 1900s, and were what made cities like New York… One of the things I was trying to find out was the kind of materials used in the buildings. Were they brick or stone?

Pete You have got timber-framed structures on the actual Castle Street frontage and then behind it looks like you have got stone structures, so this could be your Pennant rubble…

a PROPOSal

Much of the east River Drive was built on fill or on pile-supported relieving platforms. The section near bellevue Hospital (between east 23rd Street and east 30th Street) was filled with rubble from bombed british cities carried as ballast in wartime ships, and was dubbed ‘bristol basin’ at the time.

www.nycroads.com/roads/fdr

at 6pm on 24th November 1940 bristol experienced its first blitz. The raid lasted six hours and destroyed historic buildings, churches and a quarter of the medieval city, including the main shopping area which is known today as Castle Park.

www.bristolblitzed.org

Imagine lifting up a section of tarmac or paving slab in a New York street, imagine delving beneath and just below the surface uncovering the history of another city on the other side of the Atlantic.

Soon after the bombing of Bristol in 1940, rubble cleared from the city centre was used as ballast for warships on their return to the USA. What began as the fabric of Bristol ended up being used to reclaim a section of the East River in New York between East 23rd Street and East 30th Street. Known locally as the ‘Bristol Basin’, the now four-lane Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive was pile-driven on Bristol rubble lining the banks of the river.

There is a sense that this dislocation of substance mirrors a diaspora of people through war and economics. So, working with a city archaeologist, and in an act of restitution, I propose excavating a section of the basin to retrieve and return a symbolic weight of Bristol’s history to its own streets.

How will we know what is from Bristol and what is not? The materials used to build the historic mediaeval streets are well known. The type of brick and stone local to Bristol will, I imagine, still be at odds with their current location.

NOTES

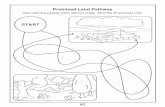

The Promised land

The Promised Land was filmed at the opening of Cabot Circus Shopping Centre on the

25th September 2008. Except for titles and credits the filmed footage is unedited.

a weight of stone carried from China for you

By locating the grid references on Google Earth it is possible to track the exact route

of the journey. Several additional images from the journey have also been uploaded to

Google Earth from the relevant locations. http://earth.google.com

The kerbstone is visible on the central avenue crossing Penn Street and entering

Cabot Circus.

100% Ford Mondeo

The Ford Mondeo concrete columns are visible on levels three and four of the Cabot

Circus car park.

bS1 – NY 10016 – bS1

It was not until this book was in preparation that my attention was drawn to a work

by Hans Schabus of which I was completely unaware. Titled Log Book of Ballast and

commissioned by Liverpool Biennial in 2006, this piece recorded a journey Schabus

made to the east coast of America to retrieve one of the stones taken from Liverpool in

the nineteenth century for ballast on ships crossing to the USA and subsequently used

to pave streets in Savannah, Georgia. While my proposal was developed independently

in response to the specific context of the Bristol site, and with the input of Bristol-based

archaeologist James Dixon, the obvious similarities between the projects require me to

acknowledge Hans Schabus’s work from Liverpool.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As an artist working within the context of a vast, privately funded city-centre

redevelopment such as Cabot Circus, I learned that an absolutely essential ingredient in

maintaining integrity and objectivity, in steering a path through the complexity of clients,

architects, delivery teams and site contractors, is the network of personal relationships

one develops over time.

Among these relationships, none was more valuable to me than that with Sam Wilkinson

of InSite Arts, Bristol Alliance’s consultant for the whole scheme. Sam protected my

interests when I needed time, fought tirelessly on my behalf, putting across concepts

unfamiliar to a client more used to commissioning permanent work, and gave me the

confidence to pursue my ideas. What has been achieved at Cabot Circus is a tribute to

that relationship, and to Sam I owe the biggest debt of gratitude for having the faith to

appoint me in the first place and for maintaining that commitment throughout.

For a project lasting three years, a relationship built on trust and mutual respect is the

foundation of success. The development and management team of Bristol Alliance were

fantastic in their support and to them I owe my thanks.

In this particular set of works three other individuals played key roles: Kevin Hives,

formerly of Stonepave Ltd; Alex Small of Celsa; and James Dixon, a Bristol-based

archaeologist.

It was with some apprehension that I first approached Kevin Hives about the idea of

going to China and bringing back a single kerbstone from quarry-face to building site;

I imagined howls of derision. On the contrary, he embraced the idea enthusiastically,

accompanying me on the first leg of the journey to China and arranging for me to see

every part of the process – which included negotiating with the Chinese government

to secure my access to the quarry. We spent five extraordinary days in China before

departing in a truck to Beijing. As I travelled back across Russia, I continued to receive

regular text messages from Kevin, checking on my progress. What seemed like an

unlikely idea was achieved largely with Kevin’s support and that of his team in China:

Leah, Rachael, Rayleigh and Sara.

Speaking to a site worker in Bristol, I discovered by chance that all the reinforced steel

used to construct the car park at Cabot Circus was recycled scrap supplied by Celsa, a

Spanish company based in Cardiff. At Celsa I met Alex and, once again, when I proposed

tracking the recycling of a car through the whole process he very willingly gave me his

full support. Celsa’s plant in Cardiff is one of the most modern steel-producing facilities

in Europe. Every product is made from recycled scrap and computer tracking means that

from the moment the scrap enters the site it can be followed through each stage back

to the building site. Alex arranged for me to film the Mondeo as it passed through each

part of the process, arranging night visits to the foundry when necessary. The hardest

part in scrapping the car and keeping it integral was the ‘fragging’ process, when the

car is ripped to shreds in seconds. Simms Metals were equally supportive, clearing the

conveyor belt, normally solid with scrap, so that the Mondeo could be put through the

process on its own. As with all these projects, something that begins with a simple idea

depends on the motivation of many people becoming involved to make it viable. This

in part reflects the positive mutual relationships that have to exist to make possible a

redevelopment of the size of Cabot Circus.

Some time into my project in Bristol I met James Dixon, an archaeologist working

on a PhD part-funded by Bristol Alliance and with an interest in the recent history of

Broadmead. Together we walked around the city, James drawing my attention to details

of design and the hidden corners I would otherwise have completely missed. In one of

our conversations he mentioned the fact that rubble from Bristol bombsites was used as

ballast in warships returning to America. So was born the concept of a project we hoped

to develop together. The fact that it remains a proposal does not lessen its importance,

and I would like to thank James for his help in developing it thus far.

Having spent so much time hidden behind the hoardings I have found it a great help to

have advocates like Tessa Jackson and Peter Jenkinson. They have encouraged and

supported my work throughout, and I want to thank them both for the time they have

given to writing the texts for this publication.

Since most of the work I have made in relation to Cabot Circus has been ephemeral

or performance-based, the associated publications are the legacy and to some extent

the work itself. It has been a privilege to work on all four publications with Alan Ward

of Axis Graphic Design. His commitment and involvement – from cooking recipes to

photographing a street in New York, from the numerous visits to Bristol to the endless

redesigning of layouts – have gone far beyond any reasonable expectations. I hope the

publications will be a lasting testimony to the project.

Likewise, Oogoo Maia has helped me with all aspects of filming, editing and production

of the DVDs. It has been a pleasure working with him.

If I have learnt anything during the last three years, it is the value of collaboration. So I

wish to thank the above and all the countless others who have played their part in making

these works possible. Thank you.

Neville Gabie

July 2009

The Promised land

First published in September 2009

by InSite Arts,

300 Burdett Road, London, E14 7DQ

07917 153555

ISBN 978-0-9561407-0-8

© 2009 InSite Arts, The Artist and Authors

Photography © Neville Gabie. Additional

photography, Paul Grundy pp. 8 & 63, Alan Ward

pp. 49, 51, 59 (bottom) & 64

All rights reserved. No part of this book may

be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording,

or otherwise without prior written permission of the

publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A British Library CIP record is available

Book design:

Alan Ward at www.axisgraphicdesign.co.uk

Editor: Helen Tookey

Print: Editoriale Bortolazzi Stei, Verona

Video editing: Oogoo Maia