THE PLEASURES AND WONDERS OF GAMEPLAY, AS WELL AS ... · 4/17/2011 · and training, communication...

Transcript of THE PLEASURES AND WONDERS OF GAMEPLAY, AS WELL AS ... · 4/17/2011 · and training, communication...

THE PLEASURES AND WONDERS OF GAMEPLAY, AS WELL AS

THEIR DEEPER LESSONS, ARE BEING APPLIED IN FIELDS BEYOND ENTERTAINMENT

DIVERSE AS PSYCHOLOGICAL THERAPY, EXPERIENCE-BASED EDUCATION,

AND DESIGN PROTOTYPING. ^ - ^ ^

AKINGAGAMEF SYSTEM DESIGN

[By William Swartout and Michael van Lent]

July 2003/V

r-T-m&^^irf

i r. r. ^

i*

OUU) THE IDEAS AND DEVELOPMENT

lethods that make computer and^ideo games so successful as a com-" elling user experience and commer-ial market ilso be applied to

developing relatively serious-mindedjappli cat ions? There is no denying the|ippeal of computer and video games.In 2002, they accounted for $6.9 bil-lion in sales in the U.S. alone, accord-ing to the Interactive Digital SoftwareAssociation [3]. Their magnetic efFectpn children's attention is all too famil-iar to parents, particularly wh?h rhealternatives are homework and house-hold chores. But what is it about

games that makes them so appealing?And what lessons might be learnedfrom their construction that could beapplied to other applications? Here,we explore these questions, offeringseveral examples of how computergame ideas influence the architectureof systems not developed directly forentertainment.

For conventional software, design isusually driven by a specification or setof requirements, ln game design, thedriving force is the users experience.Game designers try to imagine whatplayers wilf experience as they worktheir way through the game, trying to

VIRTUAL REALITY CLASSROOM

FOR ATTENTION PROCESS

ASSESSMENT IN CHILDREN

(Al.HERT RlZZO/USC

INTEGIIATED MEDIA SYSTEMS

CENTER, LOS ANGEI.ES/

DIGITAL MEDIAWORKS, INC .,

KANATA, ONTAHIO, CANADA/

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL CORP.,

SAN ANTONIO, TX).

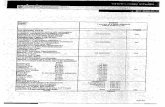

Figure 1. Screenshotftom Full SpectrumCommand highlightsembedded paths.

deliver the most exciting and com-pelling experience possible; forexample, in the recently releasedcomputer game Age of Mythol-ogy, Ensemble Studios' designers

began by calculating how long each game sessionshould take. When the game clock exceeds diis "ses-sion time limit" the quality of the game's built-in AIis dynamically scaled down, making the game easierto win, so the experience "doesn't drag out" [5].

Two key aspects of the players' experience are thegoals they pursue and the environment in which theypursue them. Game designers often seek to keep play-ers engaged by creating three levels of goals: short-term (collect the magic keys), lasting, perhaps,seconds; medium-term (open the enchanted safe),lasting minutes; and finally, long-term (save theworld), lasting the length of the g^me. The interplayof these levels, with the support of the environment,is crafted to draw players into the storyline of thegame. A good story is not simply a sequence of thingsthat happen but a careftilly constructed tapestry inwhich events are juxtaposed and emotions peak andebb. Designers purposely engage players' emotions asa way to immerse them in their games (see Whitton'sarticle in this section).

A good game is also highly interactive, deliberatelygenerating tension between the degree of control thestory imposes and the player's freedom of interaction.With no story and complete freedom of interaction,players do whatever they want, but their experiencecan be boring. On the other hand, if the story pro-vides too much control, the experience becomes morelike watching a movie than playing a game. Balancingthese two extremes is helped by the fact that a goodstoryline provides a strong context that actually limitsthe options a player might consider; they are the onlyones the game needs to allow. Gleveriy exploiting nar-rative to shape the players' experience, game designersgive players the perception they have free will, eventhough at any time their options are actually quitelimited.

Another (big) difference in game design is that,whereas most conventional software is designed tofunction in the real world, game software operates inan artificial game world designed entirely by its devel-opers. Software that operates in the real world musthandle all possible contingencies. Designers of suchsoftware have no control over the real world, so theironly option is to develop a complete solution. Gamedevelopers, on the other hand, design the world inwhich their software runs. It can be simplified or

3 4 July !00}/Vol 46. No 7 COMMUNICATIONS OFTHE ACH

made more complex, depending on the desired game-playing experience. Parts of the world may be mod-eled in great detail for a rich experience, while otherparts are only sketched out if they are intended tohave Iitde effect on the users experience. Such flexi-bility allows game developers to focus resources wherethey provide the greatest benefit, yielding faster andless-costly development.

These ideas have helped developers create immer-sive, compelling games in a cost-effective manner. Butthe goal of a game is entertainment. Could die sameideas be applied to applications with more serious-minded goals? We have identified two general classesof application that could benefit from a game-baseddesign approach. The first we call experience-basedsystems. In game design, the main focus is the user'sexperience. In identifying other applications thatmight benefit from a game-design approach, one setof applications to consider would be those that seek toinfluence users by putting them through some sort ofexperience. Such applications could involve educationand training, communication and persuasion, andexperience-based therapy. The second class involvesusing a game-based approach to construct a testbedfor emerging technologies. Games employ a devel-oper-designed world that may reflect the real worldwhile also simplifying it in many ways. A game worldmakes it possible to test emerging technologies in acomparatively rich environment before they are readyfor the ftill-scale complexities of the real world. Thegame world can also provide an environment in whicha number of technologies are integrated togetherwhile revealing interdependencies and emergingresearch issues.

Experience-based systems. All good computer andvideo games, ftom the simplest puzzle to the mostcomplex strategy adventure, share the ability to enticeplayers and immerse them in the game experience.Traditionally, immersion and entertainment go handin hand. Players are more willing to suspend their dis-belief for entertaining games—the deeper the immer-sion the more entertaining the experience. Gamedesigners thus craft every aspect of the players' experi-ence to support the desired effect and avoid breakingtheir sense of immersion; for example, simple scriptedvirtual characters that always behave believably aremore desirable than complex autonomous charactersthat occasionally make stupid mistakes, thus breakingthe sense of immersion.

Immersion is a powerful shortcut into users' mindswith potential non-game uses. In educational applica-tions, studies have shown that an immersive learningexperience "creates a profound sense of motivationand concentration conducive to mastering complex.

abstract material" [1]. Interactive, immersive experi-ence is also a powerftil tool for communication andpersuasion. Moreover, mental health professionalshave begun immersing patients in virtual experiencesto treat phobias and other mental disorders.

Experience-based education. One example of acomputer "game" built from scratch as an educationaltool is Full Spectrum Gommand (FSG), a trainingsystem developed by the University of Southern Cali-fornia's Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT) andQuicksilver Software for the U.S. Army. It draws onthe real-time strategy game genre to teach cognitiveskills, including decision making, synchronization,and leadership, to light infantry company comman-ders. Visually, it seems to users more Hke a commer-cial computer game than a training simulation with

CLEVERLY EXPLOITINGNARRATIVE to shape theplayers' experience,game designers give playersthe perception they have freewill, even though at anytime their options areactually quite limited.

real-time 3D graphics and a first-person-perspectiveplay style. However, the development team's owngaming background had a much greater influence onthe system than mere visual appearance.

FSC's training objectives emphasize combat inurban terrain. As a consequence, the developers mod-eled the urban sections in the map in much moredetail than the rural areas (compare the area aroundthe buildings with the open areas in Figure 1). This isin contrast to many conventional training simulatorsthat use a uniform terrain representation. As a result,the time spent commanding troops in urban combatis a far more complex, realistic, and challenging expe-rience than the time spent approaching the villagethrough the woods. Similarly, the AI and combatphysics simulations are careftilly tailored to be com-plex only where necessary to support the trainingexperience; for example, the AI behaves realistically in

COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM July 2003/Vol 46. No. 7 35

I hope this helpswith Diana.

What are the5Ws?

This isn t goingto help.

Figure 2. Thought bubbles inCarmen'5 Bright IDEAS(USC/ISI).

the game's urban environ-ment but is not generalenough to handle all possi-ble environments.

As with most real-time strategy games, FSC con-sists of a sequence of missions, each designed to sup-port a specific training objective. Traditional militarysimulations are also structured around instructor-designed missions. However, these missions includeextensive background stories with details on the his-tory of the situation and enemy personalities illus-trated with fictional images and profiles. Not onlydoes this context help immerse student officers in thetraining environment, the twists and turns of eachmission's narrative are designed to support the mis-sion's training objective. In early missions, when stu-dents learn the fundamentals, stories are fairlystraightforward. Later missions, seeking to challengemore advanced students, include many unexpectedtwists and third-act surprises that test their ability toreact quickly and keep a cool head under escalatingpressure.

Experience-based communicatioti. While educa-tional systems seek to impart knowledge or skills tousers, experience-based communication systems pre-

sent them with a specific viewpoint in hopes of influ-encing their beliefs and attitudes. Like Sinclair Lewis's1906 novel The Jungle, which detailed slaughterhouseconditions and resulted in extensive workplace safetyand food-hygiene reforms, experience-based systemspresent their users with the developer's viewpointunder the guise of entertainment. However, unlike anovel, experience-based systems communicate thatviewpoint from an interactive perspective.

One of the earliest examples of this fairly newapplication area is America's Army, a "strategic com-munication" game developed by the U.S. MilitaryAcademy's Office of Economic and ManpowerAnalysis 19]. America's Army is a "first-personshooter" game, based on the popular Unreal Tourna-ment game engine from Epic Games, that seeks toinform players about the Army's core values and sup-port recruitment. Like the training aids, America'sArmy is designed to communicate the desired mes-sage, including the consequences of good and badbehavior. The aspects of the game that appeal to thetarget audience (such as firing weapons and anti-ter-rorism missions) are central to the experience andmodeled in detail. It also includes the most realisticweapon models of any game we've seen, including the

36 July 2003/Vol. 46, No. 7 COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM

need to reload, weapons that jam, and snipers timingshots to their own (simulated) breathing. Aspects ofArmy life that may not appeal to the audience (suchas a strict command hierarchy) are not emphasized.

Experience-based therapy. In addition to educationand communication, experience-based systems arealso starting to be used in psychological therapy forsuch disorders as phobias and post-traumatic stress [2,8]. In exposure therapy, patients are immersed in vir-tual environments and exposed to anxiety-producingsiruiitions. The fidelity of the patients' experience iscareRilly controlled to increase realism as they becomeless sensitive. So, in early sessions a patient who fearsflying might watch a cartoonish representation oi aplane flight on a computer monitor. In later sessionsthe same patient might wear a head-mounted virtualreality display and earphones to be immersed in aphotorealistic environment. It is easy to imagineemploying a storyline along with these environmentsto help immerse patients and make the experienceseem increasingly real.

An example of a system that uses narrative exten-sively is Carmen's Brighr IDEAS 14], which uses inter-active pedagogical drama to help mothers of childrenwith cancer cope with the stress and turmoil such adisease can introduce into family life. In this system, auser first learns the backstory of Carmen, the motherof a pediatric cancer patient. Next, the user observesas Carmen discusses her concerns and problems witha simulated clinical counselor. The user can influenceCarmen's thinking by clicking on thought bubbles,like those in Figure 2. The drama unfolds based onthat interaction. The counselor discusses copingstrategies with Carmen, thereby showing them tousers so they can apply them in their own situations.

Like all powerful tools, the experience-based designapproach must be applied carefully. Without a care-fully designed experience and extensive testing, thesesystems could easily result in unwanted outcomes(such as negative training or increased phobia anxi-ety). Despite the promise of the early efforts, the bestapproaches to designing these experiences is still atopic of research and debate.

Future VisionA game's synthetic world and compelling scenariocan provide an insulating cocoon for testing new andemerging technologies before they are ready for real-world applications. The key idea is that instead ofintroducing new technologies into the complexity ofthe real world, the designers instead create an artifi-cial "game" world and introduce people and tech-nologies into that world. The fact that the artificialworld is under the control of developers changes

everything, because its content, as well as its sce-nario, can be manipulated to create a strong contextlimiting the range of possibilities the technologymust support.

Researchers in natural language processing haverecognized for some time that systems operating inthe context of a parricular task are much more feasi-ble, as the task itself provides constraints on the kindsof interactions that might occur. Adding the elementsthat make games compelling—storyline, engagingsetting, and constrained environment—carries thisnotion a step further.

The Mission Rehearsal Exercise system. A projectthat illustrates these ideas well is the MissionRehearsal Exercise system, also developed at ICT [6,7]. Its goal is to train U.S. Army lieutenants in crisis

SIMULATING REALITY isan approach that may or maynot be useful in creating abelievable experience.

decision making in a variety of situations that occur inreal-world peace-keeping and disxster-relief missions.Presented on a 30-foot-by-8-foot curved screen, thesystem places trainees in a simulated crisis (see Figure3). They interact with life-size virtual humans playingthe roles of local civilians, friendly forces, and hostileforces. These virtual humans use AI to understandwhat the lieutenant is saying, reason about the situa-tion, respond with appropriate speech and gesture,and model and exhibit emotions. Although the char-acters follow an overall scenario, their reactions arenot scripted; instead, they respond dynamically to theactions of trainees and events as they unfold in theenvironment.

The scenario currently in use is situated in a smalltown in Bosnia. It opens with a lieutenant (thetrainee) in his Humvee. He receives orders via radio toproceed to a rendezvous point to meet up with his sol-diers and plan a mission to assist in quelling a civil dis-turbance. When he arrives at the rendezvous point, heis surprised to find one of his platoon's Humvees hasbeen involved in an accident with a civilian car. A

COMMUNICATIONSOFTMEACM July 2003/Vol. 46, No 7 37

Figure 3. The MissionRehearsal Exercise system.

small boy is on the groundwith serious injuries; hisfrantic mother is nearby,

and a crowd is starting to gather. What should thelieutenant do? Stop and render aid? Proceed with themission? Different decisions produce different out-comes.

To support such a scenario, a range of technologiesmust be integrated into the virtual humans, includingspeech recognition, natural language understanding,dialogue management, natural language generation,speech synthesis, gesture generation, emotion model-ing, and task reasoning. Supporting them all is adaunting task made easier by the strong context pro-vided by the scenario, which limits the range ofresponses trainees are likely to make and in turn lim-its the size of the knowledge base needed to supportthe virtual humans' behaviors. For example, whenconfronted with the accident scene, trainees are likelyto ask what happened or about the health of theinjured child; they are unlikely to engage in casualconversation about, say, recent soccer scores.

Using the same scenario, with a commercial speechrecognizer and a simpler natural language under-standing system, Kevin Knight, a research facultymember a USC and his graduate students Michael

Laszlo and Rebecca Rees have taken this idea a stepfurther. They use the structure of the storyline to helprecover in the face of natural language failure. Forexample, at one point in the scenario, the appropriatenext step for the lieutenant to take is to secure theaccident site. If the natural language understandingsystem doesnt understand what the lieutenant says,the platoon sergeant (one of the virtual humans)might suggest that they secure the site. The naturallanguage problem is now easier, because it is focusedon recognizing a confirmation or rejection of this sug-gestion rather than a larger set of possible next moves.

If the system still fails to understand, it relaxes thecriterion for recognition. In a test with 12 subjects,each was able to complete the scenario, even thoughthe natural language recognition accuracy was onlyabout 65% and the utterance classification was onlyabout 70%. Thus, this approach allows the system'sdesigners to integrate technologies and get a feelingfor how a mature version of the system will operatebefore all the research is complete or the individualcomponents are fully robust.

ConclusionTo highlight the differences between conventionaland game systems, it is useful to consider simula-

38 July 200)/Vol. 46, No 7 COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM

tions, the class of system most ciosely related togames. In such a system, the uhimate goal is to cre-ate a virtual duplicate of teality for analysis, training,experimentation, or othet purposes. In a game, thegoal is to create a compelling experience fot theplayet. Simulating reality is an approach that may ormay not he useful in creating that experience. Thisdistinction yields several consequences. In simula-tions, hehavior (of, say, objects, vehicles, and people)should be as reahsric as possible. In games, hehaviorneeds to he believable and designed to support thedesired experience.

In simulations, the structure of the users goals(such as "attack the bridge") mimics real-lite goals. Ingames, goals (such as "slay the dragon") are selectedand designed to increase and maintain involvement.In simulations, the representation of the terrain andenvironment tends to be uniform and consistent,allowing the user to act freely within that environ-ment. In games, players have the illusion of freedomwhile following a designed experience; the designersvary the fidelity ot the representation, devoting theirgreatest effort to the parts most coupled to the users'experience.

Exploiting these design tricks, computer games cre-ate a compelling experience for practically any user

willing to play. Many of the resulting features ingames can he applied to relatively more serious-minded applications. For applications seeking toteach users through realistic experience, game designtechniques can make the experience much morememorahle. In a testhed environment, the contextand control afforded by game design techniques allowintegration of technologies and evaluation of the over-all experience, even with partial implementations. Per-haps its time to take the lessons of game designseriously. •

REFERENCES1. Dedc. C;., Salzman. M., and Loftin, B. 'riic development of a virtual

world for learning; Newtonian mechanics. In Multimedia. Hypermedia,and Virtual Reality. W Brusilovsky, P. Komniers, and N. Streir/, Eds.Springer Vcrlag, Berlin, 1996.

2, Hodges, L., Rothbauni, B.. Koopcr, R,, Opdyke, D., Meyer, T,, North,M., de Graff, J., and WHliford, J. Virtual environments for treating thefear of heights. IEEE Comput. 28.7 i^uVf 1995), 27-34.

.1. Interattive Digital Software Association; sec www,idsa.com/

4. Marsella, S., Johnson, W., and LaBote, C. Interactive pedagogical dramafor health interventions. In Proceedinp of the llth International Confer-ence on Artijicial Intelligence in Education (Sydney. Australia, July 20-242003).

5, Pottinger, D, The future of game AI, Game Develop. Mag. 7. 8 {Aug,2000), 36-39.

6. Rickel. J,, Marsella. S., Cratch, J., Hill. R.. Traum, D,, and Swartout, W.Toward a new generation of virtual humans for interactive experiences.IEEElmelti. Syst. /7.4 Ouly/Aug, 2002). 32-38.

7, Swartout, W.. Hill, R., Gratch, J,. Johnson, W., Kyriakakis. C . Labore,K,, Lindhcim, R., Marsella, S,, Miraglia, D,, Moore, B., Morie, J.,Rickel, J., Thiebaux, M., 'I'tich. L., Wliitney. R., and Douglas, J. Towardthe Holodeck; Integrating graphics, sound, character, and story. In Pro-ceeding oJ the 5th International (inference on Autonomous Agents {Mon-treal, Canada, May 28-June I). ACM Press, New York, 2001, 409-416.

8. Zimand, E., Anderson, P., Gcrshon, G., CJraap. K., Hodges. L,, andRothb.-ium, B, Viniial reality therapy: Innovative treatment for anxietydisorders. Primary Psychiatry 9. 7 (2002), 51-54.

9, Zytia, M., Hiles, J., Mayberry, A., Wardynski, C , Capps, M., Osborn,B., Shilling, R., Robaszewski, M,, and Davis. M. The MOVES Insti-tute's Army Game Project: Entertainment R&D for defense. IEEE Com-put. Graph. Appli. 23. I (Jan,/Feb, 2003). 28-36.

W I L L I A M S W A R T O U T ([email protected]) is Director of

Technology at the University of Southern CaJifornia's Institute forCreative Technologies in Los Aiigdes.M I C H A E L VAN L E N T (vanknt^'ict.usc.edu) is a research scientistat the University of Southern California's Institute for CreativeTechnologies in Los Angeles.

riit technology described here was developed with fiinds from [he U.S, Depanmeiitof the Army under contract numtn-r DAAD 1')-99-[")-0046, Any opinions, findings,and conclusions or rcctimnicndations expressed here are those of the authors and dotioi nctessarily reflect the views cif ihe U.S. Department of the Antiy,

Permissioti ro make digital i.r hard copies of all or pan ot" this work for personal orclassroom use is (;ranteti without fee provided rhar copies are not made or distributedtor profit or commercial advantage and that copies liear this tiotice and the full citationon the first ]M>;C. TO copv otherwise, to republish. to past on servers or to redistributeto lists, rpi iiires prior specific, permission and/or a fee.

O 2m?< ACM 0002-0782/03/0700 *5.0U

COMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACM |uly 2003/Vol 46, No 7 39