The Petra Museum: A New Approach to Archaeological ... · of Petra, a showcase for Jordan, and an...

Transcript of The Petra Museum: A New Approach to Archaeological ... · of Petra, a showcase for Jordan, and an...

American Journal of ArchaeologyVolume 124, Number 2April 2020Pages 333–42DOI: 10.3764/aja.124.2.0333

The Petra Museum: A New Approach to Archaeological Heritage in JordanJohn D.M. Green

museum review

www.ajaonline.org

333

Open Access at www.ajaonline.org

Supplementary Image Gallery at www.ajaonline.org

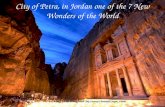

A new museum for the World Heritage Site of Petra in Jordan opened in April 2019, marking a new stage for archaeological museums in Jordan as well as providing a new showcase for Nabataean and Classical-period archaeology in the region. The museum is a welcome addition to Petra, providing a fresh approach to archaeological interpretation and museum design; presenting a number of objects for the first time; and most importantly, offering much greater accessibility for tourists and members of local communities alike. Al-though this museum has a dominant focus on the Nabataean and Roman-era city of Petra, covering the early centuries BCE and CE, the displays also tra-verse the wider history and archaeology of the surrounding region, ranging from Neolithic Bayda and Basta and Iron Age Tawilan to the Byzantine Petra Church, Crusader castles in Petra and Showbak, and the Islamic era. The mu-seum also presents important information about geology, climate, flora and fauna, agriculture, and lifestyles of the Petra region, thus going beyond ar-chaeology and providing relevant background from the area’s natural setting.1

The creation of a new museum for Petra has a long and complex history involving multiple stakeholders, architects, funding agencies, scholars, and designers. Over the years, archaeological collections from the site were stored and displayed in locations within the Petra Archaeological Park. The first museum in Petra opened in 1963 in a repurposed Nabataean rock-cut tomb carved into Jabal al-Habis. While charming and secure, and with excellent views overlooking the colonnaded street, the Petra Archaeological Museum, also known as the Cave Museum, was small and only accessible via steep steps, making it hard to reach for many visitors. In 1994, a more modern

1 In the preparation of this review, I have benefited greatly from the feedback of a num-ber of people involved in the development of the Petra Museum, in particular Koji Oyama and Midori Barada of the Japan International Cooperation Agency ( JICA); independent scholar and consultant Khairieh Amr; Ibrahim Farajat and Qais Tweissi of the Petra Devel-opment and Tourism Region Authority (PDTRA); Samia Khouri of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan; and Barbara A. Porter of the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR). I thank them sincerely for their contributions and the benefit of their experi-ence. Thanks also to JICA and the PDTRA for permissions to publish images of the mu-seum, and to the Department of Antiquities of Jordan for permission to publish images of displayed objects. An earlier review by the author appeared in The Art Newspaper (Green 2019). Figures are my own unless otherwise noted. Additional figures can be found with this review on AJA Online (www.ajaonline.org).

John D.M. Green334 [aja 124

facility opened at the western end of the colonnaded street adjacent to the Basin Restaurant, named the Petra Nabataean Museum. Both museums were at the weary endpoint of most visitors’ itineraries to the site of Petra or, for some, provided only a short stop in their climb to the ad-Deir monastery. From visitor ac-cessibility and collections management perspectives, the on-site locations of both museums were far from ideal. They closed in 2011 and 2014, respectively, as plans were put into effect by the Petra Development and Tourism Region Authority (PDTRA) to create a new and more accessible museum in the town of Wadi Musa. This process began with the opening of a new Visitor Center just inside the entrance gate in October 2014. Supported by funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the Visitor Center served as a museum for showcasing Pe-tra’s rich heritage until the completion of the new pur-pose-built museum nearby, which is under review here.

Five years in the making, the Petra Museum (fig. 1) was built with a grant equivalent to more than $7 mil-lion U.S. dollars from the Japan International Coopera-tion Agency ( JICA). The museum was inaugurated on 18 April 2019 by Jordan’s Crown Prince Hussein and the Japanese ambassador Hidenao Yanagi, along with PDTRA Chief Commissioner Suleiman Farajat.

Designed by Japanese architects Yamashita Sekkei and implemented by local engineering and architec-ture firm Maisam, the museum building is 1,800 m2 in total area, with 800 m2 of climate-controlled galleries presenting approximately 300 objects from the collec-tions of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan. The objects were drawn from the exhibit at the Petra Visi-tor Center, in addition to other collections in museum and storage facilities in Amman and in Petra itself. At the time of writing, some objects recently on loan to the “World Between Empires” exhibition at the Met-ropolitan Museum of Art in New York, were in the process of being incorporated into the new exhibits. About 50 of the objects displayed appear for the first time in a museum setting.

The museum’s location just outside the main en-trance to the Archaeological Park and Visitor Center makes it easily accessible at the end of a visit to the site, thanks to wide-ranging visitor hours that extend into early evening, though it can equally serve as an excellent previsit introduction to Petra. A shallow ornamental pool, as part of an open public space out-side the museum building helps emphasize the strong

theme of water in the displays (online fig. 1).2 A small shop can be found inside the museum at its exit. The museum is at one level, with an accessibility ramp lead-ing up to it, making it possible for wheelchair users to reach its entrance.

The Public Role of the MuseumThe creation of a new museum for Petra is part of

a broad initiative to improve and enhance resources, infrastructure, and services for the large number of tourists who visit Petra every year. Inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1985 and the Seven Wonders of the World list in 2007, the site has seen fluctuating numbers of visitors over the years, gradu-ally increasing to more than 826,000 in 2018 and ex-ceeding a million in 2019. Many travelers to Jordan may visit Petra as their primary destination, and there-fore, their experience of the country’s cultural heritage is limited largely to the town of Wadi Musa and the Petra Archaeological Park. The importance of this new well-located museum—as a gateway to the heritage of Petra, a showcase for Jordan, and an educational resource for visitors—must not be underestimated.

Another important aspect of the museum’s location is that it makes the rich heritage of Petra now much more accessible to local communities in Wadi Musa and surrounding towns, including Showbak, Tafila, Umm Seyhoun, Bayda, and the regional center of Ma’an. While Wadi Musa has become a major hub for tourism, the museum, which at the time of writing has free entry, serves as an important resource for the local community, including families and school groups. The message is clear in its position outside the gates of the Archaeological Park: this is a museum for everyone, not only foreign tourists.

The creation of the Petra Museum is significant for Jordan as a whole and especially for the southern part of the country. When the Jordan Museum opened to the public in Amman in 2008 (also a JICA-supported project), it represented the newest and most advanced purpose-built museum displaying archaeological ma-terial in the country. Another recent purpose-built archaeological museum, the Museum at the Lowest Point on Earth, opened in 2012 in Ghawr as-Safi in the Jordan Valley. Yet, in much of the rest of Jordan, archaeological collections continue to be displayed

2 See AJA Online for additional, online-only figures.

Petra Museum: A New Approach to Archaeological Heritage in Jordan2020] 335

and stored in historic stone buildings, largely because the buildings are already owned and managed by the Department of Antiquities. These structures present challenges in terms of space, accessibility, and climate control. By contrast, the Petra Museum is an aestheti-cally appealing, well-designed, purpose-built space that is attracting and can handle a large number of visi-tors. It therefore serves as an important model for fu-ture archaeological museums in the country and raises the standard of design, curation, and interpretation of archaeological heritage considerably.

The interpretive direction, themes, and selection of content for the museum were developed and co-written by an experienced team of Jordanian archae-ologists, with subsequent reviews and input at various stages by archaeological, cultural heritage, and mu-seum professionals. The final selection of objects was made by staff of the Department of Antiquities. Proj-ect directors and researchers of archaeological projects from many countries contributed images and related content for the new exhibits and multimedia features. Jordanian designers were involved in the creation of multimedia features and animations. Japanese project management staff and specialists from JICA played

an important role in coordinating various elements, including interpretive planning, research, exhibition design, and final steps bringing the museum to com-pletion. The bilingual English and Arabic text for the museum exhibits is clear, accessibly written, and not overwhelming for visitors who may choose to focus only on the introductory panels, learn details from in-dividual object labels, or delve more deeply into top-ics or subthemes represented on multimedia displays.

Thematic and Historical ApproachThe museum presents objects that range in date

from the earliest Stone Age communities to the pres-ent day. The collections are almost all archaeological and derive from excavations conducted from the mid 20th century to the present. A few ethnographic ma-terials are also on display, including textiles and jew-elry. From the outset, visitors learn that the ancient Nabataean name for Petra was Raqmu—and labels referring to Raqmu-Petra throughout the museum acknowledge the hybridity of Nabataean and classical culture and the non-Greek name of the city. This mu-seum expresses a clear desire to represent Petra’s local identity through the most recent archaeological finds

fig. 1. Exterior and front entrance of the Petra Museum, Wadi Musa (courtesy JICA).

John D.M. Green336 [aja 124

and inscriptions. The museum does not rely heavily on the classical sources that otherwise dominate the historiography of Petra.

Multiple thematic zones in the museum following a general chronological sequence are designed to en-courage visitor flow, with adequate space to stop and focus on particular artifacts or features—a sensible approach when dealing with a complex history. This arrangement allows dominant themes to be drawn out for each time period, with the peak periods of the Nabataeans in the first century BCE and first century CE providing the greatest opportunity for exploration.

The exhibits start with “Aqua Kaleidoscope,” focus-ing on water management in antiquity, its important role in this arid area, and the famed engineering and water harvesting techniques of the Nabataeans, who created channels, dams, and cisterns to provide for the city’s inhabitants. The museum lobby is infused with ambient music and an animated video showing rock-cut features in Petra as if they were filled with water. This provides a restorative and cooling effect on those arriving in the building, many of whom may well be tired and hot after hiking for miles through the site. Views through a large, double-height window open onto the attractive shallow ornamental pool that sur-rounds half of the museum. A number of quotidian artifacts, such as lead and terracotta pipe sections, are on display. The choice to emphasize water at the start of the museum is abundantly clear—water was (and still is) the most important commodity for Petra’s in-habitants. Very little of what you see in this museum or Petra itself could have been created without the skilled control of the ancient Nabataeans over this es-sential resource.

The following gallery, where the visitor is greeted by a colossal bust of the god Dushara from the Temenos Gate area, presents the “Foundations of Petra,” which provides a useful timeline from early prehistory to the present (online fig. 2). Geology, climate, and flora and fauna are introduced here, setting the scene for the im-portant role of water harvesting, farming, and pastoral life, as well as hunting, in this extreme landscape. Ex-hibits present prehistoric artifacts associated with the early farming villages of Neolithic Bayda and Basta, which date broadly to the ninth to the sixth millennia BCE. A number of mortars used in grain processing, stone points used in hunting, and ornaments worn by early inhabitants are presented.

A small section dedicated to the Iron Age and Persian-period kingdom of Edom features objects from

the sites of Tawilan and Umm el-Biyara and includes a display of gold jewelry from Tawilan. This section and other content make clear the distinction between ancient Edomites and the incoming Nabataeans from the south, while acknowledging that many of the trade routes used later by the Nabataeans were already estab-lished by the Edomites.

A large circular space forms the centerpiece of the museum, with sculptural and architectural elements from Nabataean and Roman Petra arranged around its perimeter (fig. 2). This is the most visually impressive and stimulating space in the building. Named “Active Nabataeans,” it features an appealing and informative animated video projected onto the floor at its center that illustrates key themes and historical events asso-ciated with the ancient Nabataeans. These range from their settlement in Petra in the fifth century BCE to the expansion of the incense trade routes in the Levant in the third century BCE and their peak of monumental building in the first centuries BCE and CE to eventual Roman annexation in the second century CE.

Sculptural elements on display include pieces that have been overseas on loan or in storage in Petra for several years, such as an important but fragmentary bronze sculpture of Artemis and a few pieces that have never been displayed before in a museum context, such as a winged Eros holding two winged lions (fig. 3).

Many will be familiar with famous sculptures from Petra’s Temenos Gate area and the Petra Great Temple that have appeared in traveling exhibitions in recent decades, including “Petra Rediscovered” at the Cincin-nati Art Museum,3 “Petra: Miracle of the Desert” at the Antikenmuseum in Basel, Switzerland,4 and “World Between Empires” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.5 Here, the open circular space allows room for the sculptures to breathe and be appreciated as works of art in their own right. But as with much of Nabataean sculptural art, the original architectural context is elusive; although useful multimedia screens provide graphics and some architectural overviews of the temples of Petra, it is still difficult for visitors to visualize how these impressive elements might have been displayed or received in antiquity—and this may be one important area for future consideration in this space.

3 Markoe 2003.4 Schmid et al. 2012.5 Fowlkes-Childs and Seymour 2019.

Petra Museum: A New Approach to Archaeological Heritage in Jordan2020] 337

fig. 2. “Active Nabataeans” gallery with floor projection and sculpture around the perimeter.

fig. 3. Sculpted block featuring Eros flanked by winged lions, first century CE, Petra. “Active Nabataeans” gallery.

John D.M. Green338 [aja 124

What is striking in this gallery is that visitors can see both iconic and aniconic styles side by side, from simple baetyls thought to represent al-Uzza or Isis (e.g., a stone idol from az-Zantur in Petra) with their simplified, stylized facial features, to an expressive Roman-era marble torso of Venus from Petra’s theater. This gallery is therefore a key venue for the discussion of Petra’s eclectic visual representations in sculpture, which evoke Graeco-Roman, Arabian, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian and Parthian styles. The circular de-sign of the space, however, denies the opportunity for an uninitiated visitor to explore Petra’s art historical diversity in any structured way.

The next set of galleries presents aspects of life and death. “Nabataean Zenith” focuses on the famous Trea-sury tomb at Petra (the Khazna) and explores recent archaeological findings from the Department of Antiq-uities excavations of the early 2000s that shed light on rituals and identity over time. For example, a projected animation shows the sequence in the construction of earlier tombs leading up to the creation of the Khazna monument and its now buried plaza (fig. 4). Displays show that the monuments were not only locations for burying the dead but also spaces used by the living for commemoration rituals. New information is presented for the first time in this public setting, including a fo-rensic reconstruction made from the skull of one of the Treasury tomb’s occupants (online fig. 3), helping to bring the past to life and assign an identity to the oth-erwise faceless Nabataeans. A reconstruction of Tomb 62A, the so-called Incense Tomb, includes a series of Nabataean fine ware painted bowls, which contained the remains of incense offerings, surrounded by silhou-ettes of family members, as well as the metal plaque that was affixed above the tomb chamber. Also on dis-play are the worn and fragmentary sandstone head of a lion and the muzzle of a horse, which once formed part of the Khazna complex and were found among the fallen debris below the tomb during excavations.

“Nabataean Life” features objects of daily use and elaborative elements from villas and domestic settings, including fresco paintings and architectural features from Wadi Musa. Dominating half of this space is an architectural cutaway reconstruction of a hypocaust system of the winter reception room from the first-century CE Nabataean mansion at az-Zantur, an im-portant villa in Petra excavated by Swiss archaeologists in the 1990s. A mosaic from Wadi Musa is installed beneath a glass floor, allowing visitors to walk over it and gain a sense of life in a Graeco-Roman style villa.

A large section of first-century CE wall painting, also from Wadi Musa, features bird imagery and hints at the diverse motifs that once decorated the more af-fluent homes. Also exhibited are a variety of other richly painted architectural fragments from the villa at az-Zantur. All this helps provide context and vibrant color to the past and offers a much needed domestic context to counterbalance the tombs and temples that otherwise dominate Petra’s archaeology.

The adjacent “Nabataean Expressions” gallery pres-ents more sculpture and inscriptions and delves into aspects of the Nabataean state and economy, as well as scripts and linguistics (online fig. 4). This is the most historically minded part of the museum, reflecting on the rise as well as decline of the Nabataean kingdom, which was closely tied to its trading partners. A series of important inscriptions shows the evolution and variety of scripts in use, from the Nabataean script de-rived from Aramaic, to Greek and, more rarely, Latin. Coinage, although presented in high-level graphics and on a multimedia screen, does not have its own specific display. Other aspects of the economy, including ce-ramic production, are briefly covered in this gallery, illustrated with late Nabataean pottery kiln wasters from Wadi Musa.

The “Waning of Petra” gallery refers to the period of Roman annexation and covers the Byzantine, Me-dieval (Frankish and Ayyubid), Mamluk, and Otto-man periods through a series of large window cases that present a lot of history in a relatively small space. Exhibited here for the first time, after its purposeful removal from the site due to the impact of erosion, is an important Greek inscription dated to the era of the Roman annexation of Petra in the early second cen-tury CE. It is one of the few inscriptions from the city itself that refers to its Greek name, “Petra Metropolis” (online fig. 5). Previously exposed on the colonnaded street of Petra, the inscription is an important addition to the museum, now safeguarded from the elements.

A visually appealing display (fig. 5) related to Late Roman and Byzantine Petra, features a large panther-handled marble vase dated to around 200 CE that was found in pieces in excavations of the Byzantine-era Petra Church, a building dated to the fifth to sixth centuries CE. In addition, this case presents one of two recently discovered (in 2016) and conserved statues from the North Ridge excavations.6 The famous “Petra

6 Morris 2018.

Petra Museum: A New Approach to Archaeological Heritage in Jordan2020] 339

fig. 5. Display featuring Roman and Byzantine objects in the “Waning of Petra” gallery.

fig. 4. Video projection showing chronological development of the Khazna in the “Nabataean Zenith” gallery.

John D.M. Green340 [aja 124

Papyri” found in the debris of the church in 1993 are not yet exhibited but may be added in the future, which would require a special display case to minimize light exposure (as has been used at the Jordan Museum in Amman, for example). The exhibits from Medieval and Islamic periods are somewhat sparse, and presum-ably they await the addition of material in storage or future discoveries, for example from nearby Showbak.

The final gallery in the museum is called “Revital-ization of Petra,” which focuses on the site’s story from rediscovery by European explorers in the early 19th century to the dozens of archaeological and conserva-tion projects being conducted across the Archaeologi-cal Park in recent times. A video presented alongside traditional dress and jewelry on the other side of the gallery is an effective feature that connects the liv-ing people of Petra with past and present traditions through a focus on the revival of local handicrafts, water management, and the significance of the site of Jabal Haroun—where stands the shrine of Aaron, brother of Moses—a place of religious significance for Jews, Christians, and Muslims. In its assessment of the history of exploration in Petra, a list of international and Jordanian projects gives a sense of the extensive history of archaeological work in the Petra region from the 1920s to the present, dominated initially by Brit-ish and American projects and then joined by French, Italian, and a wide range of others. As a snapshot, a panel at the end indicates the growth in the number of projects from the 1970s to the 1990s and early 2000s. The 1990s was a peak decade of archaeological explo-ration in Petra, especially at the Petra Great Temple, Petra Church, and Temple of the Winged Lions, and at Jabal Haroun, Wadi Farasa, and az-Zantur, to name just a few projects.

A few things that could have been highlighted in this part of the museum include a discussion of important archaeological excavation and site preservation initia-tives at Petra. With each turn of the trowel, sites are exposed, and this unfortunately makes them more vulnerable to the elements as well as to animal and ad-ditional human activity. Another aspect in need of pre-sentation is the problem of looting of archaeological sites in the Petra region and the illicit sale of antiqui-ties, which continues to this day. Within this museum filled with well-excavated and provenienced archaeo-logical objects, this aspect should receive more atten-tion—and if not here, then the theme of preservation of heritage needs more exposure for visitors elsewhere

at this World Heritage site. The topic is briefly covered in a short orientation film for tourists in the nearby Visitor Center, but more should be said about it.

Multimedia ContentThe added value of multimedia content cannot be

overstated, as the supplementary information allows for a “deeper dive” into many of the exhibition’s themes and subthemes. There are more than 20 multi media touchscreens throughout the museum as well as a smaller number of video displays, including projec-tions and television screens. The touchscreens do not serve as substitutes for standard graphics and labels in the galleries. Rather, their role is to provide more infor-mation if you have the time and desire to explore fur-ther. If you read everything available in the museum, including the touchscreen content, you will need a visit of several hours or multiple visits.

The multimedia touchscreens are neither obtrusive nor inconspicuous, and they provide supporting con-tent for the thematic zones of the museum. The con-tent is extensive, however, and for some visitors could be overwhelming. The museum, therefore, might also provide this content as an online educational resource for those interested in learning more before or after their visit. The screens could potentially be used to refer to or provide more detailed information about specific objects that they are placed next to—for ex-ample, exploring aspects of technology or art history, helping visitors appreciate how objects were made, or exploring the scientific analysis of artifacts. It may be noted that craft and technology were aspects strongly represented in displays in the Petra Visitor Center (2014–2019) that do not have much prominence in the new museum.

The history of the Nabataeans from written sources, which are largely Greek and Roman, is understated in the museum, with content focusing more on Petra’s local identity. It could, however, have been useful to include more about the ancient textual sources for Petra on a multimedia screen. Although much content is presented about the Romans, there is no mention of important relations between the Nabataeans and the neighboring Judaean kingdom in either the main gallery text or the multimedia touchscreens. Such epi-sodes in history are mute within the museum, though important within a broader historical narrative.

Apart from the multimedia touchscreens, perhaps the most striking use of visual technology in the

Petra Museum: A New Approach to Archaeological Heritage in Jordan2020] 341

museum is the video projection in the central area of “Active Nabataeans,” which tells the story of the Nabataeans and Petra between the fifth century BCE and the second century CE. Here, the timeline and essential elements are presented through animated silhouettes of figures from antiquity and illustrated images of artifacts with simple and concise captions. For example, for the fifth century BCE, the narrative unfolds in subtitles: “Arab Nomadic Tribes, the Naba-taeans, arrived from Arabia into Southern Jordan. They had a friendly encounter with the civilised Edomites. Welcomed, they began setting encampments in the area.” Subsequently, for the third century BCE: “The Nabataean nomadic tribes expanded their territory into Hawran, the Negeb and Sinai. The main traded products that brought in most of their wealth were frankincense and myrrh. They also traded in per-fumes.” For the second century BCE, the narrative states: “The Nabataeans established a kingdom with Raqmu, later known as Petra, as its capital. Through a spirit of democracy, while led by a royal family, . . . they settled in the city amid tranquility and abundance. . . . The Nabataeans became a regional power with a vested interest in protecting the trade routes they controlled.”

The approach is simple but effective, a kind of evo-lutionary nomad-to-kingdom narrative, though subse-quently dealing with the decline of Nabataea beginning in the second century CE. If visitors experience this video projection only, they will gain a general sense of the timeline and key defining features of Nabataean history and archaeology.

Presenting the Archaeology of Petra, and Potential for Increased Engagement

The museum’s presentation of recent discoveries highlights how scholarship on Petra and the Naba-taeans has evolved in recent years, incorporating dis-coveries made in the last two or three decades that are changing and refining a picture of the past. This is defi-nitely an archaeological museum, and the interpretive, curatorial, and design team should be congratulated on an excellent achievement. As with all museums, there are tweaks and label rewrites or redesigns that can be done in the future, and the addition of new objects is to be expected. At the time of writing, a new Petra Mu-seum guidebook was in press and will soon be avail-able for visitors.

Although the space is relatively small, the potential for this museum to become a hub for public educa-tion, outreach, and research engagement is high. The museum will evolve and develop in the future as ad-ditional staff and technical resources are integrated into its operations. Currently, it has limited storage space for artifacts and no dedicated conservation lab. Larger, purpose-built storage facilities are very much desired, and these aspects of collections management and preservation are a focus for the future, according to the recently published Petra World Heritage Site Inte-grated Management Plan.7 The nearby Visitor Center will support the new museum and the archaeological site, with a focus on temporary displays on ongoing research, excavation or conservation work at Petra.8

Investment in staff and resources related to educa-tion and outreach are also listed in future plans for Petra, which will be of great benefit for schools, mem-bers of local communities, and tourist visitors. Areas for museum education, temporary exhibitions, work-shop spaces, and conferences could be among some of the possibilities.

Some suggestions for the museum might include more prominent or immersive visualizations of Petra or of specific buildings and monuments, particularly for visitors who may not be physically able to get to all of Petra in person. For example, new technologies allowing 3D virtual reality viewing experiences could bring the past to life for visitors without taking up much space and could prove very popular.

A few categories of objects are either underrepre-sented or not yet on display. As mentioned above, coinage of the Petra region is only represented in a few places, yet it provides a great opportunity to focus on the development of the local economy as well as rep-resentations of rulers and sacred symbols over time. Only three of the series of well-known sculpted heads, associated with a palatial structure in nearby Bayda (Little Petra) and excavated in 2005,9 are exhibited in the new museum. As mentioned above, some of the “Petra Papyri” may be on exhibit in the future, though finding space will be a challenge.

Another opportunity for the future may be to de-velop object-focused interactive displays that explore

7 Cesaro and Orbasli 2019.8 Cesaro and Orbasli 2019.9 Bikai et al. 2008.

J.D.M. Green, Petra Museum and Archaeological Heritage in Jordan342

ancient craft and technology. This growing trend in many art and archaeology museums, using graphics and videos to help demonstrate sequences of produc-tion and creation of artifacts, allows the visitor to have a deeper understanding of craft techniques and the ef-forts of artisans in antiquity. Similar methods can be employed to present conservation stories related to the scientific study and preservation of objects.

Yet, these are small suggestions that would augment what is already a great success and achievement. The new Petra Museum is representative of several recent museums and visitor centers that have emerged in Jor-dan in recent years. With Jordan undergoing a cultural and tourism resurgence at the present time, the Petra Museum sets the tone for the future of archaeological heritage in Jordan and the wider region.10

John D.M. GreenAmerican Center of Oriental Research (ACOR)P.O. Box 2470 Amman [email protected]

10 Conflict of interest declaration: This review of new per-manent displays at the Petra Museum is based on visits by the author following its opening, augmented with information gathered from people involved in this major initiative. I declare that the views expressed in this review are my own and do not reflect the views of the American Center of Oriental Research (ACOR), the Petra Development and Tourism Region Author-ity (PDTRA), or the Department of Antiquities of Jordan. I de-clare that while I was not personally involved in the development of the new Petra Museum, my role as an employee of ACOR and as project director of the Temple of the Winged Lions Culture Resource Management Initiative brings me into close contact and collaboration with the PDTRA and the Department of An-tiquities in Jordan through a range of projects related to archae-ology, conservation, and cultural heritage management.

Works Cited

Bikai, P.M., C. Kanellopoulos, and S.L. Saunders. 2008. “Beidha in Jordan: A Dionysian Hall in a Nabataean Land-scape.” AJA 112(3):465–507.

Cesaro, G., and A. Orbasli, eds. 2019. Petra World Heritage Site Integrated Management Plan. Amman: UNESCO.

Fowlkes-Childs, B., and M. Seymour. 2019. The World Be-tween Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East. New York and New Haven: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press.

Green, J. 2019. “Petra’s Rich Heritage Goes on Show for All to See.” The Art Newspaper 313:30. www.academia.edu/39321108/_Petras_rich_heritage_goes_on_show_for_all_to_see_

Markoe, G. 2003. Petra Rediscovered: The Lost City of the Nabataean Kingdom. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Morris, M. 2018. “Conservation and Restoration of the Petra North Ridge Aphrodite Statues.” ACOR Newsletter 30.2:9.

Schmid, S., E. van der Meijden, A. Bignasca, and A.F. Voege-lin. 2012. Petra: Begleitbuch zur Ausstellung “Petra: Wunder in der Wüste. Auf den Spuren von J.L. Burckhardt alias Scheich Ibrahim.” Basel: Verlag Schwabe AG and Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig.