THE PARAGENESIS OF PYROPHANITE FROM SIERRA DE COMECHINGONES, CÓRDOBA, ARGENTINA · 2007. 6. 6. ·...

Transcript of THE PARAGENESIS OF PYROPHANITE FROM SIERRA DE COMECHINGONES, CÓRDOBA, ARGENTINA · 2007. 6. 6. ·...

-

155

The Canadian MineralogistVol. 42, pp. 155-168 (2004)

THE PARAGENESIS OF PYROPHANITE FROM SIERRA DE COMECHINGONES,CÓRDOBA, ARGENTINA

FEDERICA ZACCARINI § AND GIORGIO GARUTI

Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Via S.Eufemia, 19, I-41100 Modena, Italy

ARIEL ORTIZ-SUAREZ AND ANDRES CARUGNO-DURAN

Departamento de Geología, Universidad Nacional de San Luis, Chacacabuco, 5700 San Luis, Argentina

ABSTRACT

Pyrophanite (MnTiO3) has been discovered for the first time in Argentina, associated with metamorphosed Fe ore in theSierra de Comechingones, Province of Córdoba. The Fe ore mainly consists of magnetite, and contains large grains of Ti-richmagnetite, showing a complex unmixing assemblage composed of pyrophanite, manganoan ilmenite, an aluminous spinel, andhematite. The gangue minerals associated with the oxides are, in order of decreasing abundance, clinopyroxene, garnet, titanite,amphibole, clintonite, calcite, chlorite, quartz and rare epidote. Electron-microprobe analyses show extensive solid-solution amongthe end-members pyrophanite, ilmenite, and geikielite (MgTiO3). The unmixed assemblage may have been derived from oxida-tion of a former Mn–Mg-rich magnetite–ulvöspinel solid solution, under metamorphic conditions. The lack of Mn in the silicategangue associated with the Fe ore excludes the possible influence of Mn-rich fluids during metamorphism, and suggests that Mnwas an important constituent of the original oxide protolith. Geothermometry applied to the chlorite associated with the oxidesyielded temperatures as low as 300–350°C, possibly consistent with the closure of the metamorphic system. However, texturaland mineralogical evidence suggest that the temperature of metamorphism was much higher, and possibly reached a stage ofpartial melting.

Keywords: pyrophanite, magnetite, ilmenite, clintonite, chlorite, Sierra de Comechingones, Argentina.

SOMMAIRE

Nous avons trouvé la pyrophanite (MnTiO3) en association avec un minerai de fer métamorphisé à Sierra de Comechingones,province de Córdoba; c’est la première fois que ce minéral est signalé en Argentine. Le minerai, à prédominance de magnétite,contient aussi des grains grossiers de magnétite titanifère qui fait preuve d’une démixion complexe, menant à un assemblage depyrophanite, ilménite manganifère, un spinelle alumineux, et hématite. Les minéraux de la gangue associés aux oxydes sont,classés selon leur abondance, clinopyroxène, grenat, titanite, amphibole, clintonite, calcite, chlorite, quartz et, plus rarement,épidote. Les analyses à la microsonde électronique révèlent une étendue marquée de solution solide impliquant les pôlespyrophanite, ilménite, et geikielite (MgTiO3). Cet assemblage de démixion pourrait avoir été dérivé d’une oxydation d’unprécurseur comme une solution solide magnétite–ulvöspinelle riche en Mn et Mg, sujet à des conditions métamorphiques.L’absence de Mn dans la gangue silicatée associée au minerai de fer semble exclure l’influence d’une phase fluide riche en Mnau cours du métamorphisme, et semble plutôt indiquer que le manganèse était important dans l’oxyde précurseur. Lagéothermométrie fondée sur la chlorite indique des températures de l’ordre de 300–350°C, peut-être réalistes pour le stade ultimedu métamorphisme. Toutefois, d’après les critères texturaux et minéralogiques, la température de métamorphisme étaitconsidérablement supérieure, et aurait peut-être même atteint un stade de fusion partielle.

(Traduit par la Rédaction)

Mots-clés: pyrophanite, magnétite, ilménite, clintonite, chlorite, Sierra de Comechingones, Argentine.

§ Present address: Institute of Geological Sciences, University of Leoben, Peter Tunner Straße 5, A-8700 Leoben, Austria.E-mail address: [email protected]

-

156 THE CANADIAN MINERALOGIST

mentary units and Cretaceous to Tertiary volcanic units(Gordillo & Lencinas 1979).

Pyrophanite was discovered in mafic–ultramaficrocks of Sierra de Comechingones (southern Sierras deCórdoba) at latitude 32°26' South and longitude 64°34'West (Fig. 2). The mineral is part of an oxide assem-blage constituting lenses of Fe ore associated with apolymetamorphic sequence of serpentinite, amphibolite,gneisses, minor marble and pegmatite dykes (Guereschi& Baldo 1993, Guereschi & Martino 2002, 2003). Gab-bros and granites are the only intrusive igneous rocks inthe area. The pyrophanite-bearing samples were col-lected in one small pit (5 � 2 m) dug for exploration.Unfortunately, field relationships of the orebodies withtheir host rocks are not exposed in the pit and could notbe unequivocally established by surface exploration ofthe surrounding area because of the strong metamorphicoverprint and intense deformation.

ANALYTICAL METHODS

Eleven polished sections and five thin sections wereobtained from eight samples of the Fe ore, and werestudied by both reflected and transmitted light micros-copy. Pyrophanite and the associated minerals wereanalyzed with an electron microprobe at the Universityof Modena and Reggio Emilia, using an ARL–SEMQinstrument, operated at an excitation voltage of 15 kVand a beam current of 15 nA. The detection limits foreach element sought, as well as corrections for the in-terferences, were automatically established with the up-dated version 3.63, January 1996, of the PROBEsoftware (Donovan & Rivers 1990). Natural albite, mi-crocline, clinopyroxene, olivine, chromite, ilmenite andspessartine were used as standards. The K� X-ray lineswere used for all the elements of interest. The ferric ironcontent of oxide minerals was calculated from ideal sto-ichiometry.

PETROGRAPHY OF THE FE ORE

On the scale of the hand sample, the Fe ore consistsof oxides arranged in millimetric bands alternating withthe gangue minerals in a proportion of about 50% byvolume. Results of the microscope study show that theore-mineral assemblage is dominated by magnetite, ac-companied by ilmenite, pyrophanite, green spinel andrare hematite, whereas sulfides are absent. The gangueminerals associated with the oxides are, in order of de-creasing abundance, clinopyroxene, garnet, titanite,amphibole, clintonite, calcite, chlorite, quartz and rareepidote. The oxide–gangue relationships indicate equi-librium recrystallization of the mineral assemblage un-der metamorphic conditions, with formation of mosaictextures, development of near-120° triple junctions (Fig.3A). The texture also displays reciprocal inclusions ofoxides and silicates and an atoll-shape intergrowth of

INTRODUCTION

Pyrophanite, MnTiO3, is a rarely encountered mem-ber of the ilmenite group. It was discovered in the man-ganese ore of the Harstig mine, Pajsberg, Sweden(Hamberg 1890). By the end of the forties, only twoother localities were found, in Brazil (Derby 1901, 1908)and in Wales (Smith & Claringbull 1947). At present,more than thirty occurrences are known world-wide, andin most of them, pyrophanite is associated with sedi-mentary or metamorphosed manganese deposits.Pyrophanite has also been discovered in epithermal andhydrothermal manganese deposits. Furthermore,pyrophanite was found associated with metamorphosedzinc- and manganese-rich deposits. Occasionally it hasbeen encountered in banded iron formation. Pyrophanitemay also occur associated with gneisses, granitic rocks,alkaline complexes and carbonatites. It has also beenreported to occur in serpentinites and even in meteor-ites (Petaev et al. 1992, Krot et al. 1993).

In spite of the impressive number of new reports ofpyrophanite, only a few of them give a detailed descrip-tion of its composition and the phase relations of themineral. To the best of our knowledge, pyrophanite hasnever been found in Argentina. In this paper, we reportthe first information about pyrophanite from Sierra deComechingones, Province of Córdoba, and provide anextended set of electron-microprobe data on pyrophaniteand the associated oxides and silicates, along with ob-servations on paragenesis and phase relations. The com-position of pyrophanite from Sierra de Comechingonesis compared with chemical data from other occurrencesworldwide reported in the literature. The data obtainedare used to better define the chemical–physical condi-tions in the metamorphic rocks of Sierra deComechingones that led to the formation of pyrophaniteand its associated minerals.

GEOLOGICAL BACKGROUNDAND INFORMATION ABOUT THE SAMPLES

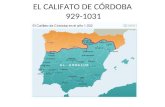

The Sierras de Córdoba (Fig. 1) is located in centralArgentina between latitude 30° and 33° South. Its gen-eral geological setting corresponds to a low-angle sub-duction zone in which a series of basement blocksup-welled during the Andean orogenesis (Isacks 1988,Jordan & Allmendinger 1986). The crystalline basementis mainly composed of different metamorphic rocks,such as migmatites, gneisses, minor marble and am-phibolites, intruded by Paleozoic granites with smallamounts of mafic–ultramafic rocks units (Gordillo &Lencinas 1979). The metamorphic rocks are related tovarious events that took place between the Precambrianand the lower Paleozoic (Kraemer et al. 1995) or be-tween the Cambrian and the Ordovician (Rapela et al.1998, Sims et al. 1998). Occasionally, the basementrocks are covered by Upper Paleozoic to Cenozoic sedi-

-

PYROPHANITE FROM CÓRDOBA, ARGENTINA 157

the oxide minerals with lobate boundaries, as a result ofmetamorphic cocrystallization (Fig. 3B).

Magnetite is the most common oxide, followed inorder of abundance by Ti-rich magnetite. The latter isclearly distinguished from normal magnetite because ofits lower reflectance and because of the ubiquitouspresence of exsolution lamellae of ilmenite-series min-erals and aluminous spinel. Pyrophanite and ilmeniteoccur exclusively associated with Ti-rich magnetite inthe form of lamellae and as a partial corona at the rim ofgrains of Ti-rich magnetite (Fig. 4). The aluminousspinel systematically occurs in the coronas, the textureindicating that the mineral is part of the exsolution as-semblage, although it has been observed also as freegrains in the gangue matrix of the Fe ore. Hematiteforms lamellae in normal magnetite, arranged in ageometric pattern reflecting (111) crystallographic

planes of the mineral host, as typical in “martite” re-placement textures (Fig. 3B). Clinopyroxene, typicallywith a mosaic texture, is the major constituent of thegangue (Fig. 3A). Garnet appears either as idiomorphiccrystals (Fig. 4B) or large poikilitic plates includingclinopyroxene and oxides (Figs. 4C, D). Garnet alsooccur included in the oxides (Figs. 4A, B, D, E). Titaniteusually occurs as large lobate grains associated with theoxide minerals (Fig. 3B). Calcite, quartz, chlorite andclintonite are encountered as minor or accessory miner-als randomly distributed in the gangue matrix.

THE COMPOSITION OF PYROPHANITEAND ASSOCIATED MINERALS

The pyrophanite has reflected-light properties verysimilar to those of ilmenite. It shows a distinct

FIG. 1. Simplified geological sketch-map of a portion of the Sierras de Córdoba showingthe location of the investigated area (based on Kraemer et al. 1995).

-

158 THE CANADIAN MINERALOGIST

bireflectance from bluish grey to grey and strong anisot-ropy varying from grey to brownish grey. Internal re-flections were not observed. One can distinguish the twophases only on the basis of chemical data. Representa-tive results of electron-microprobe analyses ofpyrophanite, ilmenite and the other associated oxides arepresented in Table 1. Reciprocal variations of the majoroxides MnO, FeO and MgO are shown in Figure 5. Theoxides MnO and FeO show clear negative correlationas a result of a complete range of solid solution fromilmenite (Fe0.9Mn0.1)TiO3 to pyrophanite (Fe0.2Mn0.8)TiO3, the compositional variation being independent of

their location, be it in lamellae or coronas. Their Mgcontent is invariably lower than 6 wt% MgO, and noneof the compositions enters the field of geikielite(MgTiO3). The highest Mg contents (> 4 wt% MgO)are found in one group of intermediate compositionsbetween manganoan ilmenite, (Fe0.7Mn0.2Mg0.1)TiO3,and ferroan pyrophanite, (Fe0.3Mn0.4Mg0.3)TiO3. Thereason for the behavior of Mg is not understood, al-though it would appear to be independent of texturaldevelopment.

Magnetite is pure Fe3O4 with trace amounts of Ti(

-

PYROPHANITE FROM CÓRDOBA, ARGENTINA 159

magnetite has Ti contents varying from 1.06 up to morethan 15 wt% TiO2. Compositions of the green spinel arereferable to the general formula (Fe,Mg)Al2O4 havingFe > Mg (hercynite) or Mg > Fe (spinel sensu stricto).Hercynite usually is enriched in Ti and Mn with respectto spinel, and both minerals contain appreciable amountsof Zn (1.79–3.21 wt% ZnO).

The results of electron-microprobe analyses ofgangue silicates are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Theclinopyroxene has the composition of augite with 1.75–2.32 wt% TiO2, but no K and Na. The garnet displays

an intermediate composition between andradite andgrossular, with low Mn (

-

160 THE CANADIAN MINERALOGIST

CHLORITE THERMOMETRY

Chlorite, in most of the investigated samples, occursas lamellar aggregates intergrown with the ore minerals(Figs 3B, 4), suggesting a common origin. Composi-tional variations of trioctahedral chlorites are believedto reflect physical–chemical conditions of crystalliza-

tion. In particular, the amount of IVAl substituting for Siin the tetrahedral site is temperature-dependent, increas-ing with depth in hydrothermal, diagenetic or metamor-phic systems. The thermometric significance of theanalyzed chlorite is not affected by alkali contamina-tion (Frimmel 1997), usually less than 0.1 atom % Ca +Na + K. Treatment of the chlorite data with the equa-

FIG. 4. Reflected-light (plane-polarized) microphotographs of the pyrophanite lamellae and coronas associated with Ti-richmagnetite. The long side of the pictures is 0.55 mm. 1: pyrophanite, 2: Ti-free magnetite (in some cases with hematitelamellae), 3: aluminous spinel, 4: garnet, 5: chlorite.

-

PYROPHANITE FROM CÓRDOBA, ARGENTINA 161

-

162 THE CANADIAN MINERALOGIST

tion of Cathelineau (1988) yielded results in the range351–393°C. This range of temperature is shifted towardslightly lower values (300–320°C) if the equation ofKranidiotis & MacLean (1987) is used.

COMPARISON WITH PYROPHANITE DATAIN THE LITERATURE

The compositions of minerals of the pyrophanite–ilmenite series from Sierra de Comechingones are plot-ted in terms of FeO–MnO–MgO (Fig. 6), and comparedwith compositions of pyrophanite and coexisting il-menite and geikielite taken from the occurrences listedin Table 4, for which chemical data are available. TheMg-poor compositions from Sierra de Comechingonesplot along the pyrophanite–ilmenite join together withmost compositions from the literature, confirming theexistence of a complete solid-solution between the twoend members, at negligible or very low contents of thegeikielite component (

-

PYROPHANITE FROM CÓRDOBA, ARGENTINA 163

and magnesian ilmenite, locally reaching the composi-tion of pyrophanite and geikielite, are formed by reac-tion of ultramafic rocks with hydrothermal fluids (Liipoet al. 1994a).

The pyrophanite and manganoan ilmenite from Si-erra de Comechingones are metamorphic minerals. Thetextural relationships suggest that both phases and theirTi-rich magnetite host formed by unmixing from a

(Fe,Ti)-oxide precursor, the composition of which isprobably referable to a member of the magnetite–ulvöspinel solid solution, although with substantial sub-stitution of Mn and Mg for Fe2+, and containing minoramounts of Al and Zn. According to experimental data(Buddington & Lindsley 1964), the solubility of il-menite in magnetite is too limited to account for theformation of lamellae assemblages such as those de-

-

164 THE CANADIAN MINERALOGIST

scribed here, by simple subsolidus exsolution. The largevolume of ilmenite lamellae inside magnetite requiresthat the magnetite–ulvöspinel precursor underwent oxi-dation-induced reactions under metamorphic conditions.

The presence of Mn and Mg in the magnetite–ulvöspinel precursor led to the formation of pyrophaniteand manganoan ilmenite containing appreciable

geikielite component at Sierra de Comechingones. Inother occurrences associated with metamorphosed ma-fic–ultramafic rocks, it has been proposed that Mn andMg might have been added to the oxide-forming sys-tem from an external source by metamorphic diffusionor reaction with hydrothermal fluids. In our case, thecomposition of the gangue silicates suggests that such a

FIG. 6. Compositions of pyrophanite and manganoan ilmenite of Sierra de Comechingones plotted in the system FeTiO3–MnTiO3–MgTiO3. Compositional data from the literature are shown for comparison (see Table 4 for references). Fields ofpyrophanite (P), ilmenite (I) and geikielite (G) are shown.

-

PYROPHANITE FROM CÓRDOBA, ARGENTINA 165

-

166 THE CANADIAN MINERALOGIST

process may hold for Mg, but does not fit for Mn, sincethis element is present only in andradite–grossular atconcentrations lower than 1.03 wt% MnO. Therefore,we suggest that Mn was probably present in the Fe ox-ide of the original protolith. The nature of the protolithat Sierra de Comechingones and its metamorphic evo-lution are so far unclear, and will be the subject of fur-ther investigation.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

1) Metamorphosed Fe ore in Sierra de Comechin-gones, Argentina, contains pyrophanite and manganoanilmenite as exsolution lamellae inside Ti-rich magne-tite. The Ti-rich magnetite coexists, at the thin sectionscale, with Ti-free magnetite.

2) The microprobe-derived compositions presentedhere, together with literature data, document the exist-ence of extensive solid-solution among the end mem-bers: pyrophanite (MnTiO3), ilmenite (FeTiO3), andgeikielite (MgTiO3).

3) Textural and compositional relationships supportthe hypothesis that the unmixing assemblage pyro-phanite–magnetite may have been derived by equilibra-tion of a precursor Mn–Mg-rich magnetite–ulvöspinelsolid solution.

4) The lack of Mn in the silicate minerals associ-ated with the Fe ore seems to exclude the possible in-flux of Mn-rich fluids during metamorphism, andsuggests instead that Mn was an important constituentof the original oxide protolith.

5) The lowest temperatures, obtained from chlorite,vary from 300 to 351°C, possibly consistent with theclosure of the metamorphic system. However, texturaland mineralogical evidence suggest that the metamor-phic temperature was much higher and possibly reacheda stage of partial melting. The high-temperature Mn–Mg-rich magnetite–ulvöspinel solid solution that wasthe precursor to the exsolution assemblage pyrophanite– manganoan ilmenite – Ti-rich magnetite possiblyformed from such a molten fraction, coexisting with aresidual Ti-free magnetite (R.F. Martin, pers. commun.).

6) This is the first documented occurrence ofpyrophanite and clintonite in Argentina.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Prof. Carlos Costa,Universidad Nacional de San Luis (Argentina), for sup-port during the field activities. We greatly acknowledgethe constructive comments by Alexandre Cabral andRaul Lira. Special thanks are due to Robert F. Martinfor his useful suggestions and revision of the Englishtext. The Italian authors are grateful to the MIUR(COFIN 2001, Leader: Prof. C. Cipriani) for financialhelp.

REFERENCES

ACHARYA, B.C., RAO, D.S. & SAHOO, R.K. (1997): Mineral-ogy, chemistry and genesis of Nishikhal manganese ores ofSouth Orissa, India. Mineral. Deposita 32, 79-93.

BROUSSE, R. & MAURY, R.C. (1976): Paragenèse mangané-sifère d’une rhyolite hyperalcaline du Mont-Dore. Bull.Soc. Fr. Minéral. Cristallogr. 99, 300-303.

BUDDINGTON, A.F. & LINDSLEY, D.H. (1964): Iron–titaniumoxide minerals and synthetic equivalents. J. Petrol. 5, 310-317.

CABRAL, A.R. & SATTLER, C.D. (2001): Contrasting pyro-phanite–ilmenite solid compositions from the ContaHistoria Fe–Mn deposits, Quadrilatero Ferrifero, MinasGerais, Brazil. Neues Jahrb. Mineral., Monatsh., 271-288.

CASSIDY, K.F., GROVES, D.I. & BINNS, R.A. (1988): Manga-noan ilmenite formed during regional metamorphism ofArchean mafic and ultramafic rocks from Western Aus-tralia. Can. Mineral. 26, 999-1012.

CATHELINEAU, M. (1988): Cation site occupancy in chloritesand illites as a function of temperature. Clay Minerals 23,471-485.

CRAIG, J.R., SANDHAUS, D.J. & GUY, R.E. (1985): PyrophaniteMnTiO3 from Sterling Hill, New Jersey. Can. Mineral. 23,491-494.

DASGUPTA, S., FUKAUAKI, M. & ROY, S. (1984): Hematite–pyrophanite intergrowth in gondite, Chikla area, SausarGroup, India. Mineral. Mag. 48, 555-560.

DERBY, A.O. (1901): On the manganese ore deposits of theQueluz (Lafayette) District, Minas Geraes, Brazil. Am. J.Sci. 162, 18-32.

________ (1908): On the original type of the manganese oredeposits of the Queluz District, Minas Geraes, Brazil. Am.J. Sci. 175, 213-216.

DONOVAN, J.J. & RIVERS, M.L. (1990): PRSUPR – a PC basedautomation and analyses software package for wavelengthdispersive electron beam microanalysis. Microbeam Anal.,66-68.

FERGUSON, A.K. (1978): The occurrence of ramsayite, titan-låvenite and fluorine-rich eucolite in a nepheline-syeniteinclusion from Tenerife, Canary Islands. Contrib. Mineral.Petrol. 66, 15-20.

FRIMMEL, H.E. (1997): Chlorite thermometry in the Wit-watersrand Basin: constraints on the Palaeoproterozoicgeotherm in the Kaapvaal Craton, South Africa. J. Geol.105, 601-615.

GASPAR, J.C. & WYLLIE, P.J. (1983): Ilmenite (high Mg, Mn,Nb) in the carbonatites from the Jacupiranga Complex,Brazil. Am. Mineral. 68, 960-971.

-

PYROPHANITE FROM CÓRDOBA, ARGENTINA 167

GORDILLO, C. & LENCINAS, H. (1979): Las Sierras Pampeanasde Córdoba y San Luis. II Simposio de Geología RegionalArgentina. Academia Nacional de Ciencias I, 577-650.

GUERESCHI, A.B. (2000): Estructura y petrología del basamentometamórfico del flanco oriental de la Sierra de come-chingones, pedanías Cañada de Alvarez y Río de LosSauces, departamento Calamuchita, provincia de Córdoba,Argentina. Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Nacional deCórdoba, Córdoba, Argentina.

________ & BALDO, E.G. (1993): Petrología y geoquímica delas rocas metamórficas del sector centro-oriental de laSierra de Comechingones, Córdoba. 12° CongresoGeológico Argentino y 2° Congreso de Exploración deHidrocarburos (Mendoza) 4, 319-325.

________ & MARTINO, R. (2002): Geotermometría de laparagénesis Qtz + Pl + Bt + Grt + Sil en gneises de altogrado del sector centro-oriental de la Sierra de Come-chingones, Córdoba. Rev. As. Geol. Argentina 57, 365-375.

________ & ________ (2003): Trayectoria textural de lasmetamorfitas del sector centro-oriental de la Sierra deComechingones, Córdoba. Rev. As. Geol. Argentina 58, 61-77.

HAMBERG, A. (1890): Über die Manganophylle von der GrubeHarstingen bei Pajsberg in Vermland. 10. Über Pyrophanit,eine mit dem Titaneisen isomorphe Verbindung derZusammensetzung MnTiO3, von Harstigen. Geol. Fören.Stockholm Förh. 12, 598-604.

HARTOPANU, P., CRISTEA, C. & STELA, G. (1995): Pyrophanite ofDelinesti (Semenic Mountains). Rom. J. Mineral. 77, 19-24.

HOLLER, W. & GANDHI, S.M. (1997): Origin of tourmaline andoxide minerals from the metamorphosed Rampura AguchaZn–Pb–(Ag) deposit, Rajasthan, India. Mineral. Petrol. 60,99-119.

HORVATH, L. & GAULT, R.A. (1990): The mineralogy of MontSaint Hilaire, Quebec. Mineral. Rec. 21, 284-359.

ISACKS, B. (1988): Uplift of the central Andean plateau andbending of the Bolivian Orocline. J. Geophys. Res. B93,3211-3231.

JORDAN, T.E. & ALLMENDINGER, R.W. (1986): The SierrasPampeanas of Argentina: a modern analogue of RockyMountain foreland deformation. Am. J. Sci. 286, 737-764.

KRAEMER, P.E., ESCAYOLA, M.P. & MARTINO, R.D. (1995):Hipótesis sobre la evolución tectónica neoproterozoica delas Sierras Pampeanas de Córdoba (30°40' – 32°40').Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina 50, 47-59.

KRANIDIOTIS, P. & MACLEAN, W.H. (1987): Systematics ofchlorite alteration at the Phelps Dodge massive sulfide de-posit, Matagami, Quebec. Econ. Geol. 82, 1898-1911.

KROT, A.N., RUBIN, A.E. & KONONKOVA, N.N. (1993): Firstoccurrence of pyrophanite (MnTiO3) and baddeleyite(ZrO2) in an ordinary chondrite. Meteoritics 28, 232-252.

LEE, D.E. (1955): Occurrence of pyrophanite in Japan. Am.Mineral. 40, 32-40.

LINDH, A. & MALMSTROM, L. (1984): The occurrence and for-mation of pyrophanite in late-formed magnetite porphy-roblasts. Neues Jahrb. Mineral., Monatsh., 13-21.

LIIPO, J.P., VUOLLO, J.I., NYKANEN, V.M. & PIIRAINEN, T.A.(1994a): Pyrophanite and ilmenite in serpentinized wehrlitefrom Ensilia, Kuhmo greenstone belt, Finland. Eur. J. Min-eral. 6, 145-150.

________, ________, ________ & ________ (1994b):Geikielite from the Naataniemi serpentinite massif, Kuhmogreenstone belt, Finland. Can. Mineral. 32, 327-332.

MARCHESINI, M. & PAGANO, R. (2001): The Val Gravegliamanganese district, Liguria, Italy. Mineral. Rec. 32, 349-415.

MASON, B. (1976): Famous mineral localities: Broken Hill,Australia. Mineral. Rec. 7, 25-33.

MELCHER, F. (1995): Genesis of chemical sediments inBirimian greenstone belts: evidence from gondites and re-lated manganese-bearing rocks from northern Ghana. Min-eral. Mag. 59, 229-251.

MENZIES, M.A. & BOGGS, R.C. (1993): Minerals of theSawtooth batholith. Idaho. Mineral. Rec. 24, 185-202.

MITCHELL, R.H. (1978): Manganoan magesian ilmenite andtitanian clinohumite from the Jacupiranga carbonatite, SaoPaulo, Brazil. Am. Mineral. 63, 544-547.

MÜCKE, A. & WOAKES, M. (1986): Pyrophanite: a typical min-eral in the Pan-African province of western and centralNigeria. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 5, 675-689.

NAYAK, B.R. & MOHAPATRA, B.K. (1998): Two morphologiesof pyrophanite in Mn-rich assemblages, Gangpur Group,India. Mineral. Mag. 62, 847-856.

PALENZONA, A. (1996): I nostri minerali: geologia e mineral-ogia in Liguria, aggiornamento 1995. Rivista Mineral.Italiana 2, 149-172.

PERSEIL, E.A., GIOVANOLI, R. & VODA, A. (1995): Evolutionminéralogique du manganèse dans les concentrations deOita (Monts de Bistrita). Carpates Orientales, Roumanie.Rom. J. Mineral. 77, 11-18.

PETAEV, M.I., ZASLAVSKAYA, N.I., CLARKE, R.S., OLSEN, E.J.,JAROSEWICH, E., KONONKOVA, N.N., HOLMBERG, B., DAVIS,A.M., USTINOV, V.I. & WOOD, J.A. (1992): The Chaunskijmeteorite: mineralogical, chemical and isotope data, clas-sification and proposed origin. Meteoritics 27, 276-277.

PORTNOV, A.M. (1965) Pyrophanite from northern Baikalia.Dokl. Acad. Sci. USSR, Earth Sci. Sect. 153, 126-138.

________ (2001): Mineralogy of the Burpala alkaline massif(north of lake Baikal). Mineral. Rec. 32, 42.

-

168 THE CANADIAN MINERALOGIST

RAO, D.S., ACHARYA, B.C. & SAHOO, R.K. (1994): Pyrophanitefrom Nishikal manganese deposits, Orissa. J. Geol. Soc.India 44, 91-93.

RAPELA, C.W., PANKHURST, R.J., CASQUET, C., BALDO, E.,SAAVEDRA, J., GALINDO, C. & FANNING, C.M. (1998): ThePampean Orogeny of the southern proto-Andes: Cambriancontinental collision in the Sierras de Córdoba. In TheProto-Andean Margin of Gondwana (R. Pankhurst & C.Rapela, eds.). Geol. Soc. London, Spec. Publ. 142, 181-217.

SASAKI, K., NAKASHIMA, K. & KANISAWA, S. (2003):Pyrophanite and high Mn ilmenite discovered in the Creta-ceous Tono pluton, NE Japan. Neues Jahrb. Mineral.,Monatsh., 302-320.

SIMMONS, W.B., JR., PEACOR, D.R., ESSENE, E.J. & WINTER,G.A (1981): Manganese minerals of Bald Knob, NorthCarolina. Mineral. Rec. 12, 167-171.

SIMS, J.P., IRELAND, T.R., CAMACHO, A. , LYONS, P., PIETERS,P.E., SKIRROW, R., STUART-SMITH, P.G. & MIRÓ R. (1998):U–Pb, Th–Pb and Ar–Ar geochronology from the southernSierras Pampeanas, Argentina: implications for thePalaeozoic tectonic evolution of the western Gondwanamargin. In The Proto-Andean Margin of Gondwana (R.Pankhurst & C. Rapela, eds.). Geol. Soc. London, Spec.Publ. 142, 259-281.

SMITH, W.C. & CLARINGBULL, G.F. (1947): Pyrophanite fromthe Benalt mine, Rhiw, Carnavonshire. Mineral. Mag. 28,108-110.

SNETSINGER, K.G. (1969): Manganoan ilmenite from a Sierranadamellite. Am. Mineral. 54, 431-436.

SUWA, K., ENANI, M., HIRAIWA, I. & YANG, T. (1987): Zn–Mnilmenite in the Kuiqi granite from Fuzhou, Fujian prov-ince, East China. Mineral. Petrol. 36, 111-120.

TSUSUE, A. (1973): The distribution of manganese and ironbetween ilmenite and granitic magma in the Osumi Penin-sula, Japan. Mineral. Petrol. 40, 305-314.

ULRYCH, J. & LANG, M. (1985): Accessory pyrophanite in gran-ite and manganojacobsite in dioritic amphibolite from theManicaragua Zone, central Cuba. Chemie der Erde 44, 273-280.

VALENTINO, A.J., CARVALHO, A.V., III & SCLAR, C.B. (1990):Franklinite – magnetite – pyrophanite intergrowths in theSterling Hill zinc deposits, New Jersey. Econ. Geol. 85,1941-1946.

WINTER, G.A, ESSENE, E.J. & PEACOR, D.R. (1981): Carbon-ates and pyroxenoids from the manganese deposit nearBald Knob, North Carolina. Am. Mineral. 66, 278-289.

ZAK, L. (1971): Pyrophanite from Chaevaletice (Bohemia).Mineral. Mag. 38, 312-316.

Received August 29, 2003, revised manuscript acceptedDecember 3, 2003.