Tourist loyalty and mosque tourism: The case of the Mosque ...

The Mosque in the West Identity-as-Form: Sculturalanalysis... · The Mosque in the West 93 both as...

Transcript of The Mosque in the West Identity-as-Form: Sculturalanalysis... · The Mosque in the West 93 both as...

The Mosque in the West

91

Cultural Analysis 6 (2007): 91-112©2007 by The University of California.All rights reserved

Identity-as-Form:The Mosque in the West1

Nebahat AvciogluColumbia University

Institute for Scholars in Paris,France

So, are you designing minarets?" Inthe early nineties while practicingarchitecture in London I often

heard people ask me this question aftertelling them that I was Turkish. At first Idid not know how to take this joke,though I assumed it was a joke since itwas followed by a smile. The frequencyof the question was enough to reveal anunderlying discursive structure whoseprinciple has been described by EdwardSaid as an ideological construction ofculture as a source of identity geared to"differentiate 'us' from 'them,' almost al-ways with some degree of xenophobia."(Said 1994, xiii ). This ideological con-struct rests on a syllogistic intellectualand moral deduction based on an essen-tialist chain of signifiers, whereby mina-rets are seen as a common denominatorof Turkish culture as well as of Islam;and, in turn, a Turkish architect is seenas the correlative bearer of that formwherever she or he may be in the world.Apart from the baffling degree of arro-gance and blindness to other historiesthat this narrative reveals, what is explic-itly suggested (and reproduced) undera smile in this ahistorical, discriminating,and deterministic portrayal of an indi-vidual (architect), a culture (Turkish), aswell as a civilization (Islam), is a post-modern Orientalism under the guise ofcosmopolitanism. As Said has shown,Orientalism led the West to see Islam, orthe East, as static both in time and place,as "eternal, uniform, and incapable ofdefining itself" (Said 1995, 15). In addi-tion, by this artificial telos , workingagainst today's liberalism, all agency andcreativity are also disturbed according topre-set categories. The contradiction be-

"

AbstractThis article is a reconsideration of the ethi-cal conceptual framework developed byEdward Said in his book Orientalismwithin an art historical context. It focusesprimarily on the relationship between formand cultural identity in the architecture ofcontemporary mosques in Europe andNorth America to discuss key theoreticalissues and current methodological tenden-cies in cross-cultural art history. The aimis to explore the highly charged topic ofcontemporary mosque architecture andminority cultural identity through theprism of what I call the Saidian turn. Thearticle concludes by suggesting that oneof the virtues of the Saidian turn is tocontextualize 'otherness' not as a culturaldead-end burdened by an over-determin-ing sense of identity but as an opportu-nity to participate in a material and open-ended becoming.

Something in me mistrusts "identity."Orhan Pamuk, 1998, 489

Nebahat Avcioglu

92

tween current tendencies towards archi-tectural open-endedness, abstraction, orinternationalism, and the cultural au-thenticity or ethnic religious identity,subconsciously or consciously impliedby the above question deserves a closerscrutiny.

Challenges to alterity, assimilation, ormulticulturalism through the "uses" ofculture and tradition are not only asymptom of latent Orientalism, theyhave also become a general phenomenonof identity politics in the face of fragmen-tation and alienation, nurturing variet-ies of religious and nationalist funda-mentalism worldwide. Critical post-co-lonial theory has in this respect pointedout many similarities between colonialand post-colonial discourses of identityclaims; both are based on a system ofambiguities, contradictions, and separa-tions, aiming at a homogeneous order bymarginalizing or alienating one another.Identity, or a sense of existential belong-ing or subjective determination, is not acoherent path through unproblematic in-stances, but a contingent and precarioussense of constructions produced by setsof mediations and discourses, "opposedessences," and a "whole adversarialknowledge built out of those things"(Said 1995, 352; Said 1994, 60). In this ar-ticle my aim is to both historicize andcontextualize Said's claim thatOrientalism is the blind spot of identitypolitics through a reading and interpre-tation of metropolitan architectural cul-ture, and in particular, of the purpose-built mosques in Europe and NorthAmerica since the late nineteenth cen-tury.

Since the emergence of post-colonialstates, mosques funded mostly by petro-dollars present us with a visual discourseof an unprecedented kind that strivestowards a formulaic objectivity orsameness, particularly, but not exclu-sively, in the West.. This discourse, as Iwill show, invents along the way tradi-tions and even an architectural ontologyof sorts in which minarets have a particu-larly enduring appeal. My study focuseson this uneasy gesture of negotiatingMuslim identity within a poor repertoireof forms. It contends that identity poli-tics is a predicament that leads to not less,but more strict methods of self-defini-tions based on even lesser signs and cat-egories of distinctions. As I shall argue,more than a mere signifier,, the minaret,together with the dome, has become astructural metonym of Muslim identitythat can no longer be read in any othercontext than the one it predetermines,even though there exist in the Muslimcountries both old and new mosqueswithout minarets and domes. Hence therelevance of the question posed by myBritish acquaintances on this topic, sinceit is a product of a tendency to denydistinctionsand foreclose alterity,, or evenhybridity,, by reducing cultures (Turkishor/and Islamic) to the homogeneousstance of a visible sign such as a mina-ret. Such a regime of referential singu-larity not only sustains the category ofidentity as a logical boundary between'us' and 'them' but also reconfigures thecolonial trope, image-as-identity, into oneof post-colonial, identity-as-image.

Highlighting Islam (symbolized bythe minaret instead of the mosque itself)

The Mosque in the West

93

both as a cultural and national markerpoints towards the enduring force of re-ligion, rather religious distinction, in theawkward articulation of national identi-ties both in the East and the West. As therelationship between religion and na-tionalist politics is being evoked follow-ing political reconfigurations and the re-surgence of Islamism in the Muslimworld, we indeed find ourselves in themidst of intense debates that continue todraw ontological and essentialist distinc-tions between the West and the East, no-tably around the questions of secular-ism2 as exemplified by recent polemicssurrounding the Muslim veil both inFrance and in Turkey or the worldwideviolence caused by the offensive Danishcaricatures of the Prophet Mohammed.We may ask if Western European iden-tity is being redefined against Islam andnot just without it (Huntington 1997).The realm of the purpose-built mosquesin Europe and North America since the1950s, following decolonization, is oneamong other realms where the religiouspolemic is taken to its extreme by bothsides in forging political identities basedon poorly defined notions of Islamic civi-lization.

The idea that globalism produced vi-brant identities in the form of the hybridis an attractive one (Bhabha 1994). Yet,there is surprisingly little evidence in thearchitecture of mosques that resists thereproduction of idealized forms and theirdistribution. Nowhere has this predica-ment manifested itself more clearly thanas in the mosques founded by the Mus-lim minorities in Europe and NorthAmerica. In describing a new multina-tional world order, Gayatri Spivak iden-

tifies this tendency as "neo-colonialism,,"that is to say,, "a displaced repetition ofmany of the old lines laid down by colo-nialism" (Spivak 1989, 269). She contin-ues, "It is in this newer context that thepost-colonial diasporic can have the roleof an ideologue" unable to negotiate theiridentity outside the context of a colonialdiscourse (Spivak 1989, 269-292). An in-vestigation into the genesis of purpose-built mosques in the West provides uswith a case study of such displaced no-tions and uncanny repetitions of colonialstyles.

***Outside of the imperial context, WesternEurope is very new to the experience ofmulti-religious and multi-cultural exist-ence. The Middle East, on the other hand,as the cradle of all three monotheisticreligions, would be unthinkable withoutthe co-existence of synagogues,churches, and mosques however conten-tious that co-existence might still be. Thisdifference, as we shall see, also effects theappropriation of foreign architecturalforms into an indigenous context. Untilvery recently, according to sociologists,Muslims in Europe were usually per-ceived as transient immigrants, refugees,or negligible ethnic minorities, ratherthan as part of communities deservingtheir own places of worship or culturalinstitutions. In this sense the Orientalistcolonial discourse was a function or by-product of the distance between thedominant center and the dominated pe-riphery. Thus the early appropriations ofcultural forms from the East were basedon synoptic views of the history of Is-lamic architecture From the second half

Nebahat Avcioglu

94

of the eighteenth century onwards, themosque, with its dome and minaret, wassingled out as the stylistic/formalmetonym of the Muslim 'other.' It be-came a leitmotif in what is known as 'ex-oticism' or turquerie in architecture.Mosque-like buildings,, mostly based onthe Turkish model-- since the "Turk" it-self was a synonym for the Muslim'other'-- transfigured into garden orna-ments all over Europe (Figs. 1 and 2)Examples of this transfiguration includethe Turkish Mosque at Kew Gardens inLondon built in 1762, the Mosque at theSchloss Garten in Schwetzingen con-structed in 1776, and the Mosque at theArmainvilliers, near Paris, designed in1785. Needless to say none of these build-ings were functional. Although Frederickthe Great of Prussia went so far as tothink about establishing a workingmosque as part of his enlightenmentproject of religious tolerance, the foun-dation of such a mosque in Western Eu-rope has its much more humble originsin the late nineteenth century.

Fig. 1 The Turkish Mosque, Kew Gar-dens, London, UK, Sir William Cham-bers, 1762. Plans, Elevations, Sectionsand Perspective Views of the Gardensand Buildings at Kew in Surry Lon-don: 1763.

Fig. 2 The Mosque, Schloss Garten,Schwetzingen, Germany, Nicolas dePigage, 1775. Photograph by PeterRichter.

With the dawn of industrialism in theearly nineteenth century, however, theseornamental buildings were replacedwith functional ones clad in freely mixedarchitectural idioms of the East for play-ful aesthetic reasons. Although continu-ing to resemble mosques with theirdomes and minarets, they functioned asbathhouses (such as those at Leeds or atTsarskoye Selo in St. Petersburg c.1852),or as steam-driven pump stations (likethe one built at Potsdam near Berlinc.1842), and even as a cigarette factory(Figs. 3, 4 and 5). This last example, con-structed in Dresden, Germany in 1909 bythe architect Martin Hammitzschisseveral stories high and features a mix-ture of Middle-Eastern styles (Wefing1997, 18-20). Since 1998 there has beenan attempt by the Muslims living in thiscommunity to reclaim the building as amosque because it is said to carry keyreligious motifs such as the dome andminaret, even though no call to prayercould be allowed from the so-calledminaret, which actually functions as achimney.

The Mosque in the West

95

Fig. 3 Steam Driven Pump Station,Potsdam, Germany, Ludwig Persius,ca. 1842

Fig. 4 Turkish Bath, Tsarskoye Selo,St. Petersburg, Russia, MonighettiRossi, 1852

Fig. 5 The Tobacco Factory inDresden, Germany, MartinHammitzsch, 1907

What this brief genealogy shows is thatthis formal representation of the MuslimEast has had the effect of severing formsfrom any live context—which would bedynamic, changing, and innovative—formore than two centuries. The multifunc-tional possibilities of that form also re-sulted in it being the locus of an unam-biguous collapse of culture and religioninto each other: the temporal and thespiritual, the here and the there, the nowand the always, thus performing theOrientalist trope identified by Said, ac-cording to which "Islam was the essen-tial Orient" (Said 1995, 116). This over-loaded process promoted Islam orMuslimhood in the West as if it were anationality, with one culture, one lan-guage, one identity, one form, and so on.In this abstract and uncritical semioticoperation both the signifier—form—and

Nebahat Avcioglu

96

the signified—identity—are essentiallyeither reduced to empty shells, or on thecontrary hardened into ideological'mythemes', as the example of theDresden factory demonstrates.

If eighteenth-century exoticism wasintegral to the gradual opening up ofEurope to other cultures, Orientalism—that is to say carefully studied objectifi-cation, description, and representation ofthe other became a principle feature ofnineteenth-century imperial controlagainst the possibilities of hybridizationor heterogeneity at home (although hy-bridization did sometimes occur, as inthe case of the establishment of the Turk-ish bath more often than not they weresubjected to hostile and racist attacks).3

Thus, increasingly, standardized and ide-alized purpose-built metropolitanmosques of late nineteenth and earlytwentieth centuries, while perhaps put-ting an end to the form/function discrep-ancy of the earlier period, crystallized theimage into an identity once and for all. Itis beyond the scope of this article to pro-vide a detailed history of each and ev-ery mosque built in Europe. Instead, Iwill briefly point out the underlyingmechanisms that sustained colonial sub-jection during the construction processof some of these mosques, such as theShah Jehan Mosque in Woking near Lon-don (Fig. 6), the Great Mosque of Paris(Fig. 7) and the Hamburg Mosque (Fig.8). We will see that in each case the cho-sen style of architecture was usually de-termined by the colonial presence in thatregion; that there was always a drawnout process of decision-making and con-struction during which endless financial,political, and structural limitations were

imposed; and most tellingly, that almostin all cases, while the funding was for-eign, the architect was always local.

Fig. 6 Shah Jahan Mosque in Woking,Woking, UK, William Chambers, 1889

Fig. 7 The Great Mosque of Paris,Paris, France, 1926

Fig. 8 Imam Ali Mosque, Hamburg,Germany, 1973. Photograph by GregGulik.

The Mosque in the West

97

The first mosque dedicated to Mus-lim worship in Europe was built inWoking, 25 miles southwest of Londonin 1889, without any governmental con-tributions. It was a modest project pro-moted by the Orientalist GottliebWilhelm Leitner, who had been the prin-cipal of the Punjab College in Lahore(originally a Hungarian Jew, brought upin Istanbul), and financed by Shah Jehan,Begum of Bhopal, whom the British re-stored to power in India and after whomthe mosque is named. A minor architect,William Isaac Chambers, ostensibly de-signed this tiny structure, measuringonly 16 by 16 feet, with 'recognizable'Indian features. Its façade supposedly al-luded to the famous Badshaahi Mosquein Lahore and the Taj Mahal in Agra, butit was more than anything else an impe-rialist showcase, as Mark Crinson asserts,for "a studied synopsis or distillate ofknowledge about some object imaginedas utterly other" (Crinson 2002, 82).Crinson argues in favor of visibilitygranted to a functioning mosque, basedon Homi Bhabha's notion of the thirdspace, or the interstices, to show thatmeaning becomes more ambiguous in ametropolitan context: "its appearance ofrespect or sympathy for this cultural oth-erness is part of the management of con-sent essential to the dynamics of hege-monic power" (Crinson 2002, 82). With-out undermining the complex but slowtransformation taking place withinpower dynamics, it is equally importantto interrogate the aesthetic validation ofthe mosque's appearance and the con-text from which it emerged. Declarative,'self-evident' architecture of the otherwas the metropolitan conditionality;therefore what is seemingly the granting

of religious rights with functioningmosques turns into the peremptory en-forcement of display not visibility.

The specific entanglement of sucharchitecture with British imperialism,defying productive or creative hybrid-ity, is clearly discernible if we comparethe Woking Mosque with the CrimeanMemorial Church in Istanbul con-structed twenty years earlier. The churchwas built not only for the Christians liv-ing in Istanbul but specifically for the useof British minorities. What is more, un-like Woking, the Memorial Church wasdesigned in the most fashionable styleof architecture of the time by a nativeBritish architect, but financed by the Ot-toman government. Interestingly, al-though the English toyed with the ideaof granting a similar kind of aestheticautonomy to Muslim minorities (Egyp-tians in this case) living in London dur-ing the conception phase of the LondonCentral Mosque in early twentieth cen-tury, the same imperialist logic, as weshall see, prevented its implementation(Tibawis 1983,1-4).

A formal structural comparison be-tween the Woking Mosque and the TajMahal or Badshaahi Mosque has oftenbeen neglected (Crinson 2002, 82). Con-sidering the monumental differences intheir sizes, how and in what way theyare similar is a legitimate question. Ad-ditionally, the Taj Mahal is not even amosque. In fact, formally speaking, thereis an astonishing visual proximity be-tween the Woking Mosque and, not withthe above mentioned Indian buildings,but the ornamental Turkish Mosque atKew Garden built more than one hun-dred years earlier in 1762. by Sir William

Nebahat Avcioglu

98

Chambers (see Fig. 1). Perhaps it was nota sheer coincidence that even the archi-tects shared the same name. We find inboth cases not only a use of simple ar-chitectural rhetoric based on recogniz-able signposts in the shape of domes andminaret-like structures, but also the ex-act same central buildings covered witha dome and flanked by lower pavilionsand decorated with ogee arches, urns,and crescents. This shows that, in fact,when it comes to adapting alien formsinto a dominant culture, it is not theknowledge of the 'original' that holds theauthority but the precedent that sets thestandard for what is and is not aestheti-cally acceptable . Naturally, such an ad-mission would unsettle the Orientalists'claims that they are the "agents of au-thority" (Said 1994, 19) about the East;as, for example, Leitner saw himself tobe, as evidenced by his numerous schol-arly publications (Leitner 1889, 1868).Not acknowledging this fact is one of thepitfalls of Orientalism. This comparisonclearly demonstrates that a century ofpresumably increasing knowledge hadno impact on the way in which the East-ern models were observed and imple-mented.

Like the Woking Mosque, the GreatMosque of Paris also stands out as rec-ognizably different from its surround-ings. They are also very different fromeach other, carrying the signs of their re-spective colonies in the East. The Pariscomplex, designed by a group of Frencharchitects who took their aesthetic inspi-rations from architectural idioms acrossMorocco, Tunisia, Algeria, and the fa-mous Alhambra in Spain, was completedin 1926 with the help of North Africancraftsmen. Although the site, in this case,

was given by the French governmentfollowing intense negotiations whichbegan as early as 1895, most of the fund-ing that enabled the mosque's realizationcame from overseas. The MagazineL'Architecture identified the Parismosque not only as the hallmark of thewhole of the 'Orient' but also as the tri-umphal representation of the French inNorth Africa,, lest the man on the streetsof Paris have any doubt: "What is all this…may ask the twentieth-century Pari-sian man of the street, who by chancepasses through these environs. This en-semble [the mosque], on the other hand,brings back to those who have visited ourNorth Africa, or those who have tra-versed the far and prestigious Orient, fa-miliar impressions" (Bayoumi 2000, 272).Thus the tautological representation ofthe 'other' by its 'otherness' is the essenceof an alienation process that achieves acertain kind of imperialist subjection. TheHamburg Mosque in Germany, finishedin 1973, designed by the Schramm &Elingius Archtects, with financial contri-butions from the local Iranian commu-nity and religious institutions in Iran,was similarly replete with Orientalistassumptions with its dome and twominarets (Holod and Khan, 213-232).Although the mosque is tiled with tur-quoise revetments and has a modernflare its overall appearance has an un-canny resemblance to that of the Kewmosque. In addition, its process of con-struction, fraught with conflict and con-troversy, took more than 13 years to cometo fruition.

Such genealogy has important impli-cations for our understanding of post-colonial purpose-built mosques becausewhat emerges is not a rejection, but a con-

The Mosque in the West

99

tinuation of such formally authorised, yetequally disfranchising, modes ofdiasporic self-representation. Architec-ture is often seen as fundamental in as-suming the role of a moral and physicalsignifier in and for cultures. Thusmosques in the West have become the'official' repository of identity claimsfrom all sides (Muslims, immigrants, andhost nations), articulated as they arearound a pseudo-transparency of formto meaning. George Bataille's critique ofarchitecture as having "the authority tocommand and prohibit" is justified in adiscussion of colonial and post-colonialconditionality of identity-as-image(Bataille 1997, 21). Bataille reminds usthat "when architecture is discussed it isnever simply a question of architec-ture…. [the discourse] finds itself caughtfrom the beginning in a process of se-mantic expansion that forces what iscalled architecture to be only the generallocus or framework of representation, itsground … Architecture, before any otherqualifications is identical to the space of rep-resentation" (Hollier 1989, 31). Indeed asSaid has argued, the construction of co-lonial discourses about the 'other' hasoften been a way to claim a tight controlof that space of representation; andasHomi Bhabha has shown this colonialsense made the representation of theother spin "around the pivot of the 'ste-reotype'" (Bhabha 1994, 76). This alsoholds true of the architecture of the mod-ern mosques. Despite the buildings' re-liance on technology, materials, andskills, certain essentialism about thesemosques continues to hold the space ofIslam (or for that matter Muslim cul-tures) as fixed and presents it as eitherunchangingly distinct from the 'West' or

identical everywhere in the 'East.' Eventhe most recently built mosques havefailed to produce an alternative represen-tation.

Like a spinning top, since the eigh-teenth century the 'Oriental' stereotypethus became defined by its outline, as theessence of a radical difference that couldbe realized less ambiguously. This is in-deed pushed to the extreme in twenti-eth century modernist mosque architec-ture and has, in effect, produced whatSpivak has called a "collective hallucina-tion" (Spivak 1989, 280). This should notcome as a surprise, as recent literaturehas pointed out that modernist architectsassimilated the colonial ideology of dif-ference wholeheartedly into their move-ment by endowing pure abstract formswith the notions of authority and authen-ticity (Celik 1992, 58-77). Thus, insteadof discouraging any attempt at reducingan aesthetic artifact (such as a mosque)to one of its features (such as a minaret)which pushes the association chain allthe way to the collective identity (Mus-lim) that such an artifact is supposed tohypostatize, they have instead endorsed it.

Fig. 9 The Central London Mosque,London, UK, Sir Frederick Gibberd,1977. Architects' Journal, 22 October1969.

Nebahat Avcioglu

100

The Central London Mosque atRegent's Park, which took nearly half acentury to realize, is a case in point. Theproject was political and the Muslimsliving in London became directly partici-pating members. Encouraged by the Pa-risian example, it was promoted as earlyas the 1920s by the Egyptian ambassa-dor, Hassan Nashat Pasha, and LordLloyd, Secretary of State for the Colonies,but the diplomatic antagonism over theSuez Canal and budget deficits haltedthe work until the 1940s. Also around thistime the Egyptian government grantedland and total liberty for the construc-tion of the Anglican Cathedral in Cairo,a project to be designed by Adrian Gil-bert Scott. Hoping for reciprocal atti-tudes, the Mosque Committee made ademand for a plot from the British gov-ernment while at the same time commis-sioning the Egyptian architect GeneralRamzy Omar. Although the land wasgranted, Omar's traditional plan was fi-nally thrown out, yielding to a metropoli-tan cultural anxiety. The British opted fora competition hosted in 1969 to find an'appropriate' design. Out of fifty entriesmostly from Muslim countries, SirFrederick Gibberd's modernist designwon and the work began in 1974 (Fig.9). Gibberd's design placed a greateremphasis on the purity of forms andundifferentiated specificity of dome andminaret, although the project brief in-cluded a statement that no prayer callwould be allowed from the tower. Opt-ing for a highly modernist design insteadof the truly heterogeneous Muslimprojects, clearly suggests that the use andcirculation of cultural codes was a West-ern prerogative. The complex was finally

consecrated four years later in 1978. En-tirely funded by petro-dollars, additionalMuslim contributions were assigned tothe interiors; minbars were sent fromEgypt, tiles from Turkey, and carpetsfrom Iran (Tibawis 1983, 1-4). The Func-tionalists protested against the design asbeing an empty shell, though not on thebasis that it still looked traditional, butthat it lacked the movement's integrity:"Of course, you cannot put the decor toone side. It is not the fact that it is deco-rated that upsets us, or even that it is rec-ognizably traditional in appearance, butthe fact that there is no internal logic,which ties the decor to the structure be-hind it. This makes it (at least for archi-tects) a frivolous building" (Crinson 2002,88). Even though the comment is dis-guised as a modernist lamentation, it isnot really concerned with the problemthat function doesn't follow the form,since the existence of the minaret is leftunchallenged. The modernist believesthat Islamic cultures and traditions canbe represented in simple recognizableshapes, in effect facilitated by a decisivelink between archetypes and identitypolitics. Gibberd's design was later em-braced as the prototype for the GrandMosque of Kuwait City in 1984 (Fig. 10).The favorable approach would be to readthis mosque as an instance of hybridityor as a metaphor for border crossing, butMohammed Arkoun identifies it insteadas a 'symbolic statement of power' of arising new dynasty in Kuwait rather thanas a spiritual place of worship (Frishmanand Khan 1994, 271). Such a sharing ofvisual language with the former colonialpower is indicative of a global sharingof the language of power through the

The Mosque in the West

101

desire for immediate access to anoriginary identity or tradition throughrepresentation.

Fig. 10 Kuwait State Mosque, Ku-wait, Saudi Arabia, MuhammadSaleh Makiya, 1984. Photograph bythe architect.

The predicament here is not that mod-ernism has caused forms to collapse intosignifiers of whole cultures, and in par-ticular Eastern cultures (for example, anall-subsuming Islamic 'shape' in the formof a minaret or a dome), but that theseideas have somehow converged withsome of the Muslim views particularlyendorsed by those living outside Mus-lim countries, as an effect of socio-eco-nomic violence, displacement, exile, andin general, imperialism. In Spivak'swords, "s/he is more at home in produc-ing and simulating the effect of an olderworld constituted by the legitimizingnarratives of cultural and ethnic speci-ficities and continuities, all feeding analmost seamless national identity—aspecies of 'retrospective hallucination'"(Spivak 1989, 282). Indeed more andmore purpose-built mosques in Europeand North America, mostly funded bythe Wahabi sect (Sunni fundamentalistsfrom Saudi Arabia), do seem to strivetowards a "seamless national [Muslim]

identity" inspired and guided by the co-lonial sense that the dome and minaretwere the undisputed signs, not only ofIslamic cultures, but Islam itself.

Indeed when Ziaulhaq Zia, the chair-man of the Islamic Centre of OceanCounty in the United States, was askedto describe the project for a new mosquethe first thing he declared was: "We willhave a minaret" and "We will have a dome"(Everline 2004). Seen from this perspec-tive, the question "are you designingminarets?" can be decoded on the onehand as a colonial fantasy and on theother as a post-colonial diasporic desire.The missing element in all of these is that,in actual fact, neither the Koran nor Tra-ditions—the sayings of the Prophet—dictates a shape for a mosque or its ac-companying structures. Few Muslimswould even disagree with the idea thatthere is no need for a mosque to pray.Scholars have also argued that the mina-ret was essentially an invention of for-mal archaism (simply a tower imitatinga lighthouse) and that its use in a reli-gious context was almost accidental(adhan, the Muslim prayer, by chancetook place up in the tower). The Islamicart historian Jonathan Bloom's in-depthstudy of the minaret is unequivocal: "theminaret was invented, not early in thefirst century of Islam, but at the end ofits second century, … and that in the be-ginning it had little if anything to do withthe call to prayer" (Bloom 1989, 7). AsBloom has shown, only in the thirteenthcentury did the minaret become a com-mon element of a mosque and even thenit was entangled in aesthetic and politi-cal signs of representation; its style,which was extremely varied, advertised

Nebahat Avcioglu

102

distinction not unity (Fig. 11). Indeed thedogmatic shape of mosques, with notone but several minarets, belongs to thelegacy of the Sunni Hanafi School cham-pioned by the Ottomans, the longestlived Muslim imperial power.

Fig. 12 The Manhattan Mosque inNew York, U.S.A., Minaret by AltanGursel, 1991. Photograph by AliyePelin Celik.

Such formal reductionism, transcend-ing all questions of style, design, tech-nology, culture, history, or modernity, hasnow become the orthodox principle of asingular Muslim identity. In the sameway that Charles Jencks has identified

the self-conscious classical architecture,with its principal columns and entabla-ture, with European fascism (Jencks 1987,46), so do the dome and minaret becomethe universal properties of Islamic fun-damentalism. Even the intensely de-bated design of the Manhattan Mosquebuilt in 1991 gave in to this conventionof the dome and minaret (Fig. 12). OmarKhalidi, a historian of North Americancontemporary mosques, writes that"[a]fter a long and thoughtful debate thetwo groups [Muslim financiers and non-Muslim academic advisors] agreed on a'modernist' building, but with the Mus-lim Committee forcing the inclusion ofboth a minaret and a dome, neither of themfavoured by the architects and scholars"(Khalidi 1998, 324).4 Since the minaretand the dome were claimed as divineproperties of a mosque, any rejection ofthem was seen in opposition to Islam.Indeed for most practicing Muslims, and

Fig. 11 Minarets from Turkey, Yemen, Morocco, Xinxiang, China

The Mosque in the West

103

particularly those living in the West, eventhe sheer idea of a mosque lacking aminaret and/or a dome has now cometo present a challenge of an existentialkind. Jencks's view is pertinent: "the poli-tics of the self-conscious tradition [of ar-chitecture], as one could guess, are con-servative, elitist, centralist and pragmaticwith an occasional element of mysticalfundamentalism thrown in to catalyse,or brutalise the masses" (Jencks 1987, 46).After it was decided that there would bea minaret at the Manhattan mosque, itwas separately designed by the Turkish-American architect Altan Gürsel. Therationale for this decision could be thatthe pencil-shaped Ottoman/Turkishminaret easily translates into a modernshape, but in political terms, as more andmore contemporary mosques around theworld draw on this model, it providesthe most congenial sign of the MuslimUmma (the universal community ofMuslims) as well an identification withpower (the Ottoman Empire being thelast vestige of that memory).

This insistence on minarets has nowproduced surprising new results—aminaret without a mosque. In Turkey, ina small village called Ayvalik, near Izmir(Symirna) I encountered a ruined, thusunused, mosque with a brand new mina-ret attached to it, the foundation plaquereading 2005 (Fig. 13). When I inquiredabout the mosque itself and whether itwas scheduled for a repair I was told thatit is in the process of reparation but thatthey chose to build the minaret first. Evenwhen the mosque is finally restored,what is lost in this upside down processis an enduring sentiment of spirituality.When the spectator looks at this minaret

without a mosque, he or she invests itnot with less but greater politics, perhapsthe politics of the current TurkishIslamicist regime.5

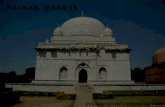

Fig. 13 Hayrettin Pasha Mosque,Ayvalik, Turkey, (converted church).Minaret dated 2005. Photograph bythe author.

There is no one methodology for un-derstanding the long catalogue of mina-rets from Manhattan to Ayvalik but it isclear that most contemporary mosquesno longer involve the makings of "a placeof worship and collective social activi-ties," but rather, as Oleg Grabar asserts,they are in the service of "a monument"symbolizing power as culture (Frishmanand Khan 1994, 245). The existence of aminaret in this case is a neutral, easilymanageable, generic trope, neatly tidy-ing so many different cultures, habits,climates, and traditions. Within such acontext it becomes apparent that legiti-

Nebahat Avcioglu

104

mizing narratives for building minaretsare not simply based on religion or his-toricity, but on sheer appearances, takenat face value, constructing a social andpolitical reality based purely on them-selves.

The problem with political Islam isthat it attaches so much value to thatform that even the outright Orientalistbuildings are recoded into consecratedones and reclaimed by Muslim minori-ties as their own. As Jencks states, "[t]heself-conscious tradition of architectureoften shows an attention to its own ac-tions which is so self-reflective as to beparalysing" (Jencks 1987, 46). TheDresden Turkish Tobacco Factory is acase in point (see Fig. 5). The attempt toclaim it as part of a Muslim cultural iden-tity, because of its dome and minaret-likechimneys, is indicative of this paradox.This is not to deny that such a recodingcould not be read as an appropriation ofpower on the part of the marginalized,but to suggest that it only serves an ideo-logical end that traps these communitiesin a perpetual state of minority and fore-closes their creative abilities. Within themetaphorical and symbolic field this fro-zen identity-as-image produces not cul-ture, but melancholy or fundamentalism.It cannot articulate difference; it only cre-ates a fictitious totality against theequally fictitious homogeneity of a hostnation.

Formal militancy, in a way, encour-ages a regime of resistance for the sakeof resistance. Indeed, in Europe andNorth America more and more mosquesare under greater scrutiny and newmosque projects are received with sus-picion. Marco Pastors, a city councillor

in Rotterdam, declared his protestagainst a new mosque which was re-cently completed in a quasi-fascist man-ner: "We want a European version of Islam,and that Islam must adapt to Europe, notEurope adapt to Islam. … [Y]ou have toearn the right to make very distinctivebuildings when you are new in a coun-try" (Knox 2004). What is in fact utterlyperverse about this statement is that ifthere is a version of Islam it is already theEuropean version. Based on these kindsof statements identity becomes a fallacy,a jail whose keys are in the pockets ofthe inmates, or as Adorno describes it,"the whole dispute resembles shadow-boxing" (Adorno 1978, 303).

There is an intrinsic difficulty tocope with open-endedness aboutcultures (in the Foucaldian sense of theterm, culture's lack of a 'pure' origin ormeaning or enclosed authority). As Saidstates : "… no one finds it easy to live un-complainingly and fearlessly, with thethesis that human reality is constantlybeing made and unmade, and thatanything like a stable essence isconstantly under threat" (Said 1994, 333).And he adds that "we all need somefoundation on which to stand; thequestion is how extreme andunchangeable is our formulation of whatthis foundation is" (Said 1994, 333). Thisquestion is important in order to preventa vicious circle of complicity in thehandling of predetermined, uncriticalclaims to identity. Equally to objectifydiscursive elements is to disentangleanalytically the ideological pre-requisites(ontological, political, and aesthetic)implicit in cultural products, and toconsider them as guiding themes in

The Mosque in the West

105

shaping one's critical stance towardsthem.

Edward Said's Orientalism has indeedforcefully thrown open Pandora's box forall of us. Scholars following the Saidianconcept contested the dominant norms(narrative) of history writing, interpre-tation, and cross-cultural interactionswithin the socio-political context of co-lonialism and post-colonialism (Celik2002, 21). But so far, contesting dominantforms (modalities) of representation re-mains unexplored. Challenges to domi-nant narratives have indeed expandedthe academic canon and even altered itshistorical interpretation. However, read-ing the proliferation of standardizedmosque architecture in the West as apost-colonial success story runs the riskof being partial to the 'other.' Consider-ing these mosques as autonomous state-ments of a single Muslim identity in theWest would also undermine the theoreti-cal issues that have identified represen-tation with power. In order to avoid ideo-logical pitfalls we must then pose thepertinent question of form, which hasbeen side-tracked by most scholars. InAdorno's words, "a work of art that iscommitted strips the magic from thework of art that is content to be a fetish,an idle pastime for those who would liketo sleep through the deluge that threat-ens them, in an apoliticism that is in factdeeply political" (Adorno 1978, 301).From this perspective it becomes clearthat a mosque without a dome or a mina-ret is not a threat to the processes of be-coming or identification. Only a discus-sion of creativity instead of identity canmake these mosques politically visible,and only then potentially existentiallyfulfilling.

This is not just a theoretical wishful-ness; alternative solutions, aestheticallycreative and non-conformist mosquesemploying modernizing elements, withor indeed without domes or minarets, doexist. Amongst them are the SherefudinMosque in Visoko, Bosnia, by ZlatkoUgljen (1980); the Plainfield Islamic Cen-tre in Indiana, USA, by Gulzar Haider(1981); the National Assembly Mosqueof Behruz and Can Cinçi, in Ankara, Tur-key (1989) (Fig. 14); Poulad Shahr inIsfahan, Iran, by Mohammad AliBadrizadeh (1991); Ilyas CavusogluCamii in Rize, Turkey, by Erhan Isözen(1993); the Nour Mosque in Gouda,Netherlands, by Gerard Rijnsdorp(1993); the Kazan Mosque in Russia, byRafik Bilyalov (1998); or the TuzlaMosque in Bosnia, by Amir Vuk (2000)(Fig. 15) to list just a few. Their forms arecontemporary and modern; here I amusing this adjective not as a Europeanprerogative but as a shorthand for a setof tendencies betraying an autonomythat, both thematically and formally, pre-sents an outward-looking cultural pro-ductivity. These mosques have none ofthe identity politics trappings; they arenot conceived as religious signposts. Themosque of the National Assembly inAnkara with its 'international' style, forinstance, takes its function as a mosquefor granted and aligns itself with a cul-tural discourse of secularism in a coun-try with a Muslim population. Thesemosques foster a sense of cultural con-text and artistic concentration, and canbe seen as not only contesting the modesbut also the dominant forms of represen-tation. This is akin to what Said saysabout the works of writers he admires,

Nebahat Avcioglu

106

such as Césaire and Walcott: "whose dar-ing new formal achievements are in ef-fect a re-appropriation of the historicalexperience of colonialism, revitalisedand transformed into a new aesthetic ofsharing and often transcendent re-for-mulation" (Said 1994, 353). One of thevirtues of the Saidian turn is tocontextualize 'otherness' not as a culturaldead-end, burdened by an over-deter-mining sense of identity, but as an op-portunity to participate in an open-ended becoming.

More recently, artists are focusing onexpressions of the Muslim way of life inthe West precisely in those terms.Bosnian-born artist Azra Aksamija, nowliving in the United States and Austria,resists the post-colonial identity-pasticheby promoting what she calls "nomadicmosques" (Aksamija 2005, 17-21) bywhich the Muslim practice of prayer canbe performed anywhere (Figs. 16 and 17).

Fig. 16 Dirndlmoschee [Dirndl DressMosque ], Azra Aksamija, 2005. Cour-tesy of the artist.

Fig. 17 Nomadic Mosque, AzraAksamija, 2005. Courtesy of the art-ist.

v

v

v

v

v

Fig. 14 Ilyas Cavusoglu Mosque,Rize, Turkey, Erhan Isözen, 1993.Photograph by the architect.

Fig. 15 Mosque of the BehrambegMadrasa, Tuzla, Bosnia-Herzegovina,Zlatko Ugljen and Husejn Dropic,1999. Photograph by Azra Aksamija

The Mosque in the West

107

According to Aksamija "…the design ofwearable mosques—clothing that can betransformed into prayer-environment…examines the notion of mosque spaceand investigates its formal limits"(Aksamija 2005, 17-21). This radicalwork also explores the themes of culturaldynamism and adaptability inherent toIslam as seen by the young Muslim art-ist: "[t]he religion of Islam" Aksamijawrites "is not understood as a static con-cept, which it often claims to be, butrather as a dynamic process that adaptsto specific geographical and cultural con-ditions" (Aksamija 2005, 17-21). Here, theexperience of the civilian massacres inBosnia and of post-9/11 politics in theUnited States places an awareness of Is-lam as a crucial space of today's globalpolitics (i.e. the need to flee or hide tosave one's life, the status of the displaced,misplaced, or refugee). But rather thanremaining frozen on a passive, victim-ized spot, Aksamija's work emphasizesthe creative dynamics of cultural de-ter-ritorialization under the figure of thenomad with her portable/wearablemosque. A mosque on the road as it werefor an undetermined becoming is ableto decode and recode and de-decode it-self with the changing landscape, poli-tics, and life in general. The signified ofthe line of flight leads not to de-politi-cize Muslim populations but to invigo-rate self-determination. In the words ofAksamija, the "success [of the project] iscontingent upon the actual wearing ofthe mosque, which can only take placeif the Muslims themselves recognize andaccept the basic ideological elasticity ofIslam" (Aksamija 2005, 17-21).

Notes1This is a revised and extended version of apaper delivered at the Conference Hommageà Edward W. Said held at the BibliothèqueNationale de France in Paris in September,2004. Research for this paper was carried outduring my Fellowship at the Columbia Uni-versity Institute for Scholars at Reid Hall inParis in 2005. More recent version of the pa-per was delivered at the symposium on TheMosque in the West organized by the AgaKhan Programme at MIT in April 2006.2The notion of secularism has now itself be-come an essentializing and chastising decoy,hiding the much more concrete issues of theuniversalist, global neo-imperialism, pre-sented either as democratic or as naturalhuman condition.3The reception of Turkish Baths in Londonin the 1860s is a case in point. One critic iden-tified the Turkish habit of washing as a bar-baric and enervating act. This is how he de-scribes it: "Turkish Bath vies with Mons. leGorilla (referring to Charles Darwin's bookOn the Origin of Species by means of NaturalSelection,1859) in attracting public attentionat the present time. This is not at all to bewondered at, seeing that the latter desires toclaim us as first cousins, while the former isgoing to assist in bringing us down to thelevel of the latter" (Avcioglu 1998, 66).4The scholars have included none other thenthe doyens of Islamic art and architectureOleg Grabar and Renata Holod (Khalidi1998, 324).5 One is immediately reminded of the poemread by the Turkish Prime Minister RecepTayyip Erdogan in 1997: "The minarets arebayonets/ the domes helmets/ the mosquesour barracks/ the believers our soldiers." Asthe first line suggests the minarets have nowbecome the proverbial political instrumentsrather than elements in an architecturalscheme.

v

v

v

v

v

v

v

Nebahat Avcioglu

108

Works CitedAdorno, W. Theodor. 1997. Functional-

ism Today. In Rethinking Architec-ture, A Reader in Cultural Theory.Edited by Neil Leach. Londonand New York: Routledge.

____. 1978. Commitment. In The Essen-tial Frankfurt School Reader. Editedby Andrew Arato and EikeGebhardt. New York: UrizenBooks.

Aksamija, Azra. 2005. NomadicMosque: Wearable Prayer Spacefor Contemporary Islamic Prac-tice in the West. Thresholds 32:17-21.

Avcioglu, Nebahat. 1998. Constructionsof Turkish Baths as a Social Re-form for Victorian Society: theCase of the Jermyn StreetHammam. In The Hidden Icebergof Architectural History. Edited byColin Cunningham and JamesAnderson. Papers from the An-nual Symposium of the Societyof Architectural Historians ofGreat Britain. London: 59-78.

Bayoumi, Moustafa. 2000. Shadows andLight: Colonial Modernity andthe Grande Mosquée of Paris.The Yale Journal of Criticism 13.2:267-292.

Battaille, George. 1997. Architecture. InRethinking Architecture, A Readerin Cultural Theory. Edited by NeilLeach. London and New York:Routledge.

Bhabha, Homi. 1994. The Location of Cul-ture. London and New York:Routledge.

Bloom, Jonathan. 1989. Minaret: Symbolof Islam. Oxford Studies in Is-lamic Art, VII. Oxford: OxfordUniversity Press.

Celik, Zeynep. 1992. Le Corbusier,Orientalism, Colonialism. As-semblage 17: 58-77.

___. 2002. Speaking Back to OrientalistDiscourse. In Orientalism's Inter-locutors: Painting, Architecture,Photography. Edited by JillBeaulieu and Mary Roberts.Durham, NC: Duke UniversityPress: 19-41.

Crinson, Mark. 2002. The Mosque andthe Metropolis. In Orientalism'sInterlocutors: Painting, Arch-itecture, Photography. Edited by JillBeaulieu and Mary Roberts.Durham, NC: Duke UniversityPress: 79-101.

Everline, Theresa. 2004. Made inAmerica: An MIT scholar's studyof the architecture of Americanmosques reveals a Muslim com-munity in search of itself. GlobeNewspaper Company, August 15.

Frishman, Martin and Hasan-UddinKhan, eds. 1994. The Mosque: His-tory, Architectural Developmentsand Regional Diversity. London:Thames and Hudson.

Hollier, Denis. 1989. Against Architecture:The Writings of George Bataille.Translated by Betsy Wing. Cam-bridge, MA: MIT Press.

Holod, Renata and Hasan-Uddin Khan,eds. 1997. The Mosque and theModern World. London: Thamesand Hudson.

v

The Mosque in the West

109

Huntington, P. Samuel. 1997. The Clashof Civilisations And the Remakingof World Order. London.

Jencks, Charles. 1987. Modern Movementsin Architecture, first published in1973, reprint of second edition.London: Penguin Books.

Khalidi, Omar. 1998. Approaches toMosque Design in NorthAmerica. In Muslims on theAmericanization Path? Edited byYvonne Yazbeck Haddad andJohn L. Esposito. USA: ScholarsPress.

Knox, Kathleen. 2004. Europe: buildingnew mosques encounter resis-tance. Radio Liberty , March 11.http://www.rferl.org.

Pamuk, Orhan. 1997-1998. White Sea isAzure. In Istanbul, un mondepluriel, Mediterraneans 10: 485-489

Said W. Edward.1994. Culture and Impe-rialism. Second edition. NewYork: Vintage Books.

____. 1995. Orientalism: Western Concep-tions of the Orient. Re-edition withAfterward, London: PenguinBooks.

Spivak, Gayatri. 1989. Who ClaimsAlterity? In Remaking History:DIA Art Foundation Discussions inContemporary Culture 4. Editedby Barbara Kruger and PhilMariani. Seattle: Bay Press: 269-292.

Tibawis, Abdul-Latif. 1983. The Historyof the London Central Mosqueand the Islamic Cultural Centre,1910-1980. In Die Welt des Islam,XXI: 1-4.

Wefing, Heinrich. 1997. VersteinertesRauchsignal, "Martin Ham-mitzsch 'Tabakmoschee Yenidze'in Dresden" Deutsche Bauzeitung,131: 18-20.

Nebahat Avcioglu

110

Nasser RabbatMassachusetts Institute of Technology,

USA

This article aspires to move the dis-course on contemporary mosquesin the West, both as architectural

objects and as framers of communalidentities, from its usual frames of refer-ence—taxonomic, typological, and sty-listic on one hand, and political, ideologi-cal, and polemical on the other—into theexpanses of critical theory. To achievethat end, in a review of importantmosque projects in Europe and NorthAmerica, the author discusses and testscurrent themes in cultural criticism, suchas the signs and boundaries of culturalterritories and cultural claims; the polar-ity of center and periphery, both origi-nal and derivative; and majority andminority. These themes were originallyformulated for the investigation of cul-tural and social politics and issues ofidentity in modern and post-colonialcontexts, but have successfully migratedin recent years to permeate the study ofcreative processes, such as architecture.

The author's examination of the de-sign and building of mosques in the Westoffers a prime opportunity to questionthe validity of geographic, historical, re-ligious, and national boundaries as dis-ciplinary dividing lines. Styles of build-ing design in the eighteenth and nine-teenth centuries constructed as frivolousexercises in stylistic exoticism resulted invarious buildings in Europe masquerad-ing as pseudo-mosques. In the variousWestern cities where new Islamic com-munities grew beginning in the 1950s,these pseudo-mosques became formal

"precedents" for the design of modernmosques seeking roots. Burdened byEurocentric administrative limitationsand ideological passions forced uponthem for a variety of reasons, these com-munities sought conformity, historicity,and authenticity in the architectural vo-cabulary of their places of worship awayfrom their Islamic home.

These developments in the West,however, are not independent from whathappened in the Islamic World in the last30-40 years, where architecture under-went a series of complex transforma-tions. Indeed, the romantic conceptionof an exotic, colorful, and religiouslydriven Islamic architecture, which wasoriginally propounded by WesternOrientalists in the nineteenth century,was challenged by new visions with thegradual collapse of the colonial rule bythe middle of the twentieth century. Theindependence movements which be-came ruling political parties in the colo-nized Islamic countries, brought withthem the more vocal and aggressive con-cepts of modernity and nationalism torepresent the architecture of their newlyconstituted states. This period, however,was short lived, succeeded and some-what supplanted by the no less passion-ate discourse on religion as identitymarker that sprang forth in the 1980s, pri-marily as a backlash to the failure of thenationalist rhetoric to encompass thecultural aspirations of the vast majorityof the common people in many countriesof the Islamic world.

This process (badly understood bymost), evolved intermittently during the1980s and 1990s in the vast majority ofthe Islamic countries and gave rise to an

Response

The Mosque in the West

111

ideology that saw Islam as identity. Theshift has been promoted by at least twoeconomically and politically dissimilar,though ultimately mutually reinforcing,social groups.

First was the reemergence of a fun-damentalist political movement in manyIslamic countries after an apparent dor-mancy of some thirty years. Spurred bythe triumph of Khomeini's Iranian Revo-lution of 1979, and vaguely conceived asa response to the perceived failures of thenational states to face up to foreign in-terference, economic corruption, andmoral decadence, the fundamentalistmovement sought a return to more au-thentic political and social foundationsto govern the Muslim Nation. Despite itsrelentless and violent attacks on what itsees as the depravity of all Western cul-tural constructs, especially those aimedat the Islamic world, the fundamentalistmovement showed surprisingly littleinterest in the conceptual contours ofvarious aspects of Islamic cultures, in-cluding Islamic architecture.

The second group to emerge in the1980s was made up of the elite of manyrecently formed nation-states of the Gulfregion, which experienced an unprec-edented prosperity and a concomitantsocioeconomic empowerment in the af-termath of the oil boom of the 1970s.Their new wealth, deeply religious andconservative outlook, and fervent questfor cultural identity combined to createa demand for a contemporary yet iden-tifiable Islamic architecture. Sincerely attimes and opportunistically at others,many architects responded by engagingin the design of various historicist styles,all modern and all dubbed "Islamic,"

sponsored by these elite groups acrossthe Islamic world or wherever new Is-lamic communities happened to congre-gate, mostly in the West.

These three phases of architecture inthe modern Islamic world—theOrientalist/colonial, nationalist, andneo-Islamist—share the same historicistdiscourse on "Islamic Architecture." Theydiffer only in the historical segment theyselect as their main reference. TheOrientalists see the dawn of Islam as thebeginning of Islamic architecture and thebeginning of the colonial age as its end,and consider all preceding or contempo-rary traditions external to it. They con-struct a continuous narrative that runsparallel to the Western architectural tra-dition but almost never intersects withit until it dissolves with the onset of mo-dernity.

Both nationalists and neo-Islamistsaccept the paradigm of cultural au-tonomy but emphasize different histori-cal trajectories. The nationalists stress thepoint in time when their putative na-tions—i.e. Turkish, Iranian, Arab—roseto prominence under Islam or brokeaway from its hegemonic grip, and con-struct their history selectively from thatmoment to the present, which they in-variably see as resurgent. They some-times search for anchoring roots in thedistant, pre-Islamic past and postulatesome latent continuity between that pastand the awakening of their nation to itstrue identity in the modern age.

The neo-Islamists, too, construct apreferred historical trajectory, which is amedley of Golden Ages stretching fromthe high Caliphate in the 8th century tothe Gunpowder Empire in the 16th cen-

Nebahat Avcioglu

112

tury. They hold that age as the fountain-head from which their architecture de-rives, yet still, in the present moment,attempt to rebuild that romantically re-membered architectural utopia usingpurely postmodern compositional andformal techniques and leaving out allthat they consider aberrant, or, to usetheir favorite term, jahili, (ignorant, aterm that usually refers to the pre-Islamicperiod in Arabia). As a result, both na-tionalists and neo-Islamists conceive"their" architecture from exclusionaryperspectives, which they unwittinglyinherited from their Orientalist predeces-sors and which resulted in the tradi-tional, rigid, and almost caricature-likearchitecture of their places of worshipboth in the Islamic World and the West.

The publication in 1978 of EdwardSaïd's seminal book Orientalism markeda turning point in the conception of Is-lamic studies in the West, but its influ-ence on design in the contemporaryworld was mostly indirect and hard togauge. Progressive architects working inthe Islamic world did begin, around thattime, to breach the artificial boundariesof their heritage and explore new designideas, but their experiments were limitedand lacked popular appeal. They chafedunder bureaucratic restrictions and theinfluence of populist movements. Per-haps their most formidable opponentwas the dominant paradigm of the en-tire discipline of architecture, which le-gitimizes a theoretically reflective andhistorically evolving Western architec-ture while casting the architecture ofother cultures as outdated and unable tobeget modern living expressions.Changing these conditions, in my opin-

ion, depends to a large extent on the sat-isfaction of two interrelated require-ments. First, these progressive architectsbuilding new mosques must resolve thetensions inherent in the discourse of con-temporary architecture and diffusedover such binary oppositions as " re-gional vs. international", "transcenden-tal vs. historical," "traditional vs. mod-ern," "vernacular vs. designed", or " staticvs. dynamic." The second requires West-ern architects and town planners andadministrators, in their capacity as primearbiters of the discipline, to reflect thethoughts and work of their newly asser-tive interlocutors from the Islamic world.