The Leeds-born Poet Laureate

-

Upload

richard-storer -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

0

description

Transcript of The Leeds-born Poet Laureate

Dr Richard StorerLeeds Centre for Victorian Studies

Leeds Trinity University

This small selection of writings by Alfred Austin was first produced for a talk which I gave at the Leeds Library on 29 April 2015. During this talk I gave an overview of Austin’s career, and some colleagues kindly assisted in reading some of the poems aloud. Together with the poems I also compiled a list of Austin’s books, almost all of which are held by the Leeds Library, included here with the poems. I would love to hear from anyone who has an interest in Austin – please do email me on [email protected].

2

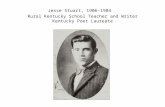

Alfred Austin, the Leeds-born Poet Laureate

Alfred Austin’s memories of his childhood in Leeds

I was born on the 30th of May 1835 at Headingley, then an outlying rural parish in the neighbourhood of Leeds, itself more like a very quiet provincial town than what is has since become under the manufacturing expansion of the last sixty years. My home, built by my Father shortly after his marriage, was thoroughly in the country; no other house intervening between it and the farther side of Woodhouse Moor. One small cluster of lowly buildings could alone be seen on the Moor, which I have heard my Father say he remembered as having been the Kennels for the local Hunt. No tall chimney, no volumes of smoke could be seen from our grounds, nothing to indicate the proximity of unpicturesque mills and furnaces. Adjoining meadows, the playground of my brothers, my sisters, and myself, widened our boundaries, that are now occupied by rows of suburban terraces and a church, or chapel, I am not certain which. But a regiment of Cavalry and a Battery of Artillery were then always stationed in Leeds; and it was on Woodhouse Moor that they executed, three or four times a week, their somewhat elementary manoeuvres. The glitter of the cavalry sabres or the sound of the first cannon-shot always aroused my interest; and I watched from the lawn with childish excitement the charging of the horses and the firing of the guns . . .

Wool-stapling, as followed by my Father, Grandfather, and Great-grandfather – the last two had passed away before I reached the age of memory – seemed to me at the time a singularly light occupation. We all had to be in the breakfast-room at nine o’clock; and Morning Prayers, read by my Father, always preceded the morning meal. When it was over, he lingered among the flowers, the poultry, and the pigeons, and not till about ten o’clock did he leave for Leeds, where, in Albion Street, his office and warehouses were. He invariably walked there and back, a distance of about two and a half miles each way; for, with the masculine habit of the day, he looked on driving in carriages, save for pleasure or very long distances, as suitable only to women. In those days, people dined at a much earlier hour than now; hence he was always home by five, frequently by four o’clock, and on Saturdays yet earlier. I mention these otherwise insignificant facts to show under what leisurely conditions business was then conducted. His remaining share in it consisted in periodical visits to London when the Wool-Sales took place, where he bought what his judgment told him the cloth manufacturers of the West Riding would be likely to require, warehousing what he bought, and selling to them the number of bales they needed. Such was the trade of Wool-stapling in those days . . .

3

From The Autobiography of Alfred Austin, Poet Laureate, 1835-1910 (1911), pp.3-4,8

4

Christmas, 1870

Heaven strews the earth with snow,That neither friend nor foe

May break the sleep of the fast-dying year;A world arrayed in white,Late dawns, and shrouded light,

Attest to us once more that Christmas-tide is here.

And yet, and yet I hearNo strains of pious cheer,

No children singing round the Yule-log fire;No carol’s sacred notes,Warbled by infant throats,

On brooding mother’s lap, or knee of pleased sire.

Comes with the hallowed timeNo sweet accustomed chime,

No peal of bells athwart the midnight air;No mimes or jocund waitsWithin wide-opened gates,

Loud laughter in the hall, or glee of children fair.

No loving cup sent round?No footing of the ground?

No sister’s kiss under the berried bough?No chimney’s joyous roar,No hospitable store,

Though it be Christmas-tide, to make us note it now?

No! only human hate,And fear, and death, and fate,

And fierce hands locked in fratricidal strife;The distant hearth stripped bareBy the gaunt guest, Despair,

Pale groups of pining babes round lonely-weeping wife.

5

Can it be Christmas-tide?The snow with blood is dyed,

From human hearts wrung out by human hands.Hark! did not sweet bells peal?No! ‘twas the ring of steel,

The clang of armed men and shock of murderous bands.

Didst Thou, then, really come? –Silence that dreadful drum! –

Christ! Saviour! Babe, of lowly Virgin born!If Thou, indeed, Most High,Didst in a manger lie,

Then be the Prince of Peace, and save us from Hell’s scorn.

We weep if men denyThat Thou didst live and die,

Didst ever walk upon this mortal sphere;Yet of Thy Passion, Lord!What know these times abhorred,

Save the rude soldier’s stripes, sharp sponge, and piercing spear?

Therefore we, Father, plead,Grant us in this our need

Another Revelation from Thy throne,That we may surely knowWe are not sons of woe,

Forgotten and cast off, but verily Thine own.

Yet if He came anew,Where, where would shelter due

Be found for load divine and footsteps sore?Here, not the inns alone,But fold and stable groan

With sterner guests than drove sad Mary from the door.

6

And thou, ‘mong women blest,Who laidst, with awe-struck breast,

Thy precious babe upon the lowly straw,Now for thy new-born SonWere nook and cradle none,

If not in bloody trench or cannon’s smoking jaw.

Round her what alien rites,What savage sounds and sights –

The plunging war-horse and sulphureous match.Than such as these, alas!Better the ox, the ass,

The manger’s crib secure and peace-bestowing thatch.

The trumpet’s challenge direWould hush the angelic choir,

The outpost’s oath replace the Shepherd’s vow;No frankincense or myrrhWould there be brought to her,

For Wise Men kneel no more – Kings are not humble now.

O Lord! O Lord! how long?Thou that art good, art strong,

Put forth Thy strength, Thy ruling love declare;Stay Thou the smiting hand,Invert the flaming brand,

And teach the proud to yield, the omnipotent to spare.

Renew our Christmas-tide!Let weeping eyes be dried,

Love bloom afresh, bloodshed and frenzy cease!And at Thy bidding reign,As in the heavenly strain,

Glory to God on high! on earth perpetual peace!

7

Versailles [Reprinted from Interludes (1872)]

From The Human Tragedy (1862 / 1876 / 1885)

[Godfrid, the hero of The Human Tragedy, remembers his lost faith and finds himself falling in love with the simple and devout Olympia, who worships daily at a shrine to the Madonna]

The tenderness which drenches the lone mind,

Insensibly as dew distilled at night,

Made him, of late, cast many a look behind

Of fondness towards a Creed abandoned quite.

He felt his hands clasped by a parent kind

In infant prayer; he saw each dear old rite;

He heard the hymns of childhood, and he breathed

The scent of flowers with sacred incense wreathed.

For not in scorn, but he, bowed down and blenched,

Had passed out from the Temple. Ere he went,

With secret tears the altar-steps he drenched,

Aware he sped to utter banishment.

From home, hearth, heaven, reluctant heart he wrenched,

The stern exiler of his past content;

Bidding adieu to Faiths which, well he knew,

Cease not to comfort, ceasing to be true.

Thus with mute wisdom seated in his mind,

And tenderness chief tenant of his heart,

He left the wasteful, turbid strifes behind,

In which the understanding ne’er take part;

And, by his very loneliness inclined8

To welcome a new anodyne for smart

Not yet quite old, he found his footsteps halt

Where Spiaggisascura fronts the waters salt.

There found he all the disenchanted crave:

Beauty, and solitude, and simple ways;

The quiet-shining hills, the long lithe wave,

Now white-fringed fretting into rough-curved bays,

Now swirling smoothly where the flat sand gave

A couch whereon to end its stormy days;

Plain folk and primitive, made courteous by

Traditions old; and a cerulean sky.

. . . But now the spot endeared to him before

By fair simplicity and lonely grace,

Had to his heart grown dearer more and more,

Since he had gazed upon Olympia’s face,

Had seen her with up-raisëd eyes adore

The sinless Mother in the sacred place,

And carried in his arms her garlands sweet,

Swift down the hill following her fawnlike feet.

He thought how good, how restful it would be,

How cool of shade when fierce suns glare and scorch,

What placid heaven from a plunging sea,

If he within the little temple’s porch

Might dwell in reverent quietude, while she,

Purer of heart, still fed the altar’s torch,

And live, despite his doubt, to her almost

9

As near as she to Heaven’s angelic host.

[Reprinted from The Human Tragedy (final version: 1885), Act II, Stanzas 50-54,57-58]

10

from The Door of Humility

He who hath roamed through various lands,And whereso’er his steps are set,The kindred meaning understandsOf spire, and dome, and minaret;

By Roman river, Stamboul’s sea,In Peter’s or Sophia’s shrine,Acknowledges with reverent kneeThe presence of the One Divine;

Who, to the land he loves so wellReturning, towards the sunset hourWends homeward, feels yet stronger spellIn lichened roof and grey church-tower;

Round whose foundations, side by side,Sleep hamlet wit and village sage,While loud the blackbird cheers his brideDeep in umbrageous Vicarage.

******

O rival Faiths! O clamorous Creeds!Would you but hush your strife in prayer,And raise one Temple for our needs,Then, then, we all might worship there.

But dogma new with dogma oldClashes to sooth the spirit’s grief,And offer to the unconsoledPolyglot Babel of Belief!

[Reprinted from The Door of Humility (1906), pp.27-28, 123]

11

Grandmother’s Teaching

Grandmother dear, you do not know; you have lived the old-world life,Under the twittering eaves of home, sheltered from storm and strife;Rocking cradles, and covering jams, knitting socks for baby feet,Or piecing together lavender bags for keeping the linen sweet:Daughter, wife and mother in turn, and each with a blameless breast,Then saying your prayers when the nightfall came, and quietly dropping to rest.

You must not think, Granny, I speak in scorn, for yours have been well-spent days,And none ever paced with more faithful feet the dutiful ancient ways.Grandfather’s gone, but while he lived you clung to him close and true,And mother’s heart, like her eyes, I know, came to her straight from you.If the good old times, at the good old pace, in the good old grooves would run,One could not do better, I’m sure of that, than do as you all have done.

But the world has wondrously changed, Granny, since the days when you were young;It thinks quite different thoughts from then, and speaks with a different tongue.The fences are broken, the cords are snapped, that tethered man’s heart to home;He ranges free as the wind or the wave, and changes his shore like the foam.He drives his furrows through fallow seas, he reaps what the breakers sow,And the flash of his iron flail is seen mid the barns of the barren snow.

He has lassoed the lightning and led it home, he has yoked it unto his need,And made it answer the rein and trudge as straight as the steer or steed.He has bridled the torrents and made them tame, he has bitted the champing tide,It toils as the drudge and turns the wheels that spin for his use and pride.He handles the planets and weighs their dust, the mounts on the comet’s car,And he lifts the veil of the sun, and stares in the eyes of the uttermost star.

‘Tis not the same world you knew, Granny; its fetters have fallen off;The lowliest now may rise and rule where the proud used to sit and scoff.No need to boast of a scutcheoned stock, claim rights from an ancient wrong;All are born with a silver spoon in their mouths whose gums are sound and strong.And I mean to be rich and great, Granny; I mean it with heart and soul:At my feet is the ball, I will roll it on, till it spins through the golden goal.

12

Out on the thought that my copious life should trickle through trivial days,Myself but a lonelier sort of beast, watching the cattle graze,Scanning the year’s monotonous change, gaping at wind and rain,Or hanging with meek solicitous eyes on the whims of a creaking vane;Wretched if ewes drop single lambs, blest so is oilcake cheap,And growing old in a tedious round of worry, surfeit, and sleep. You dear old Granny, how sweet your smile, and how soft your silvery hair!But all has moved on while you sate still in your cap and easy chair.The torch of knowledge is lit for all, it flashes from hand to hand;The alien tongues of the earth converse, and whisper from strand to strand.The very churches are changed and boast new hymns, new rites, new truth;Men worship a wiser and greater God than the half-known God of your youth.

What! Marry Connie and set up house, and dwell where my fathers dwelt,Giving the homely feasts they gave and kneeling where they knelt?She is pretty, and good, and void I am sure of vanity, greed, or guile;But she has not travelled nor seen the world, and is lacking in air and style.Women now are as wise and strong as men, and vie with men in renown;The wife that will help to build my fame was not bred near a country town.

What a notion! To figure at parish boards, and wrangle o’er cess and rate,I, who mean to sit for the county yet, and vote on an Empire’s fate;To take the chair at the Farmers’ Feast, and tickle their bumpkin ears,Who must shake a senate before I die, and waken a people’s cheers!In the olden days was no choice, so sons to the roof of their fathers clave:But now! ‘twere to perish before one’s time, and to sleep in a living grave.

I see that you do not understand. How should you? Your memory clingsTo the simple music of silenced days and the skirts of vanishing things.Your fancy wanders round ruined haunts, and dwells upon oft-told tales;Your eyes discern not the widening dawn, nor your ears catch the rising gales.But live on, Granny, till I come back, and then perhaps you will ownThe dear old Past is an empty nest, and the Present the brood that is flown.

13

*********

14

And so, my dear, you’ve come back at last? I always fancied you would.Well, you see the old home of your childhood’s days is standing where it stood.The roses still clamber from porch to roof, the elder is white at the gate,And over the long smooth gravel path the peacock still struts in state.On the gabled lodge, as of old, in the sun, the pigeons sit and coo,And our hearts, my dear, are no whit more changed, but have kept still warm for you.

You’ll find little altered, unless it be me, and that since my last attack;But so that you only give me time, I can walk to the church and back.You bade me not die till you returned, and so you see I lived on:I’m glad that I did now you’ve really come, but it’s almost time I was gone.I suppose that there isn’t room for us all, and the old should depart the first.That’s as it should be. What is sad, is to bury the dead you’ve nursed.

Won’t you have bit nor sup, my dear? Not even a glass of whey?The dappled Alderney calved last week, and the baking is fresh today.Have you lost your appetite too in town, or is it you’ve grown over nice?If you’d rather have biscuits and cowslip wine, they’ll bring them up in a trice.But what am I saying? Your coming down has set me all in a maze:I forgot that you travelled here by train: I was thinking of coaching days.

There, sit you down, and give me your hand, and tell me about it all,From the day you left us, keen to go, to the pride that had a fall.And all went well at the first? So it does, when we’re young and puffed with hope;But the foot of the hill is quicker reached the easier seems the slope. And men thronged round you, and women too! Yes, that I can understand.When there’s gold in the palm, the greedy world is eager to grasp the hand.

I heard them tell of your smart town-house, but I always shook my head.One doesn’t grow rich in a year and a day, in the time of my youth ‘twas said.Men do not reap in the spring, my dear, nor are granaries filled in May,Save it be with the harvest of former years, stored up for a rainy day.The seasons will keep their own true time, you can hurry nor furrow nor sod:It’s honest labour and steadfast thrift that alone are blest by God.

15

You say you were honest. I trust you were, nor do I judge you, my dear:I have old-fashioned ways, and it’s quite enough to keep one’s own conscience clear.But still the commandment, ‘Thou shalt not steal’, though a simple and ancient rule,Was not made for modern cunning to baulk, nor for any new age to befool;And if my growing rich unto others brought but penury, chill, and grief,I should feel, though I never had filched with my hands, I was only a craftier thief. That isn’t the way they look at it there? All worshipped the rising sun?Most of all the fine lady, in pride of purse you fancied your heart had won.I don’t want to hear of her beauty or birth: I reckon her foul and low;Far better a steadfast cottage wench than grand loves that come and go.To cleave to their husbands, through weal, through woe, is all women have to do:In growing clever as men they seem to have matched them in fickleness too.

But there’s one in whose heart has your image dwelt through many an absent day,As the scent of a flower will haunt a room, though the flower be taken away.Connie’s not so young as she was, no doubt, but faithfulness never grows old;And were beauty the only fuel of love, the warmest hearth would soon grow cold.Once you thought that she had not travelled, and knew neither the world nor life:Not to roam, but to deem her own hearth the whole world, that’s what a man wants in a wife.

I’m sure you’d be happy with Connie, at least if your own heart’s in the right place.She will bring you nor power, nor station, nor wealth, but she never will bring you disgrace . They say that the moon, though she moves round the earth, never turns to him morning or nightBut one face of her sphere, and it must be because she’s so true a satellite;And Connie, if into your orbit once drawn by the sacrament sanctioned above,Would revolve round you constantly, only to show the one-sided aspect of love.

You will never grow rich by the land, I own; but if Connie and you should wed,It will feed your children and household too, as it you and your fathers fed.The seasons have been unkindly of late; there’s a wonderful cut of hay,But the showers have washed all the goodness out, till it’s scarcely worth carting away.

16

There’s a fairish promise of barley straw, but the ears look rusty and slim:I suppose God intends to remind us thus that something depends on Him.

17

God neither progresses nor changes, dear, as I once heard you rashly say: Your schools and philosophies come and go, but His word doth not pass away.We worship Him here as we did of old, with simple and reverent rite:In the morning we pray Him to bless our work, to forgive our transgressions at night.To keep His commandments, to fear His name, and what should be done, to do – That’s the beginning of wisdom still; I suspect ‘tis the end of it too.

You must see the new-fangled machines at work, that harrow, and thresh and reap;They’re wonderful quick, there’s no mistake, and they say in the end they’re cheap.But they make such a clatter, and seem to bring the rule of the town to the fields:There’s something more precious in country life than the balance of wealth it yields.But that seems going; I’m sure I hope that I shall be gone before:Better poor sweet silence of rural toil than the factory’s opulent roar.

They’re a mighty saving of labour, though; so at least I hear them tell,Making fewer hands and fewer mouths, but fewer hearts as well:They sweep up so close that there’s nothing left for widows and bairns to glean;If machines are growing like men, man seems to be growing a half machine.There’s no friendliness left: the only tie is the wage upon Saturday nights:Right used to mean duty; you’ll find that now there’s no duty, but only rights.

Still stick to your duty, my dear, and, then, things cannot go much amiss.What made folks happy in bygone times will make them happy in this.There’s little that’s called amusement, here; but why should the old joys pall?Has the blackbird ceased to sing loud in spring? Has the cuckoo forgotten to call?Are bleating voices no longer heard when the cherry-blossoms swarm? And home, and children, and fireside lost one gleam of their ancient charm?

Come, let us go round; to the farmyard first, with its litter of fresh-strewn straw,Past the ash-tree dell, round whose branching tops the young rooks wheel and caw;Through the ten-acre mead that was mown the first, and looks well for aftermath,Then round by the beans – I shall tire by then, - and home up the garden-path,Where the peonies hang their blushing heads, where the larkspur laughs from its stalk – With my stick and your arm I can manage. But see! There, Connie comes up the walk.

18

[First published in Soliloquies in Song (1882)]

19

from The Tower of Babel (1890)

[A Child’s Prayer in Shinar]

Almighty Being, That dost dwell

In the high Heavens apart,

Alone, and inaccessible

Save to the seeing heart;

Shelter our herds, increase our flocks,

Ripen the swelling grain,

Breathe life into the barren rocks,

And send the timely rain.

Grant to my father length of days,

And to my mother give

A spirit meek, that in Thy gaze

She humbly still may live!

Cause me to feel, through good, through ill,

How poor a thing am I,

And, when I have fulfilled Thy will,

Resignedly to die.

20

Jameson’s Ride

‘Wrong! Is it wrong? Well, may be:But I’m going, boys, all the same.Do they think me a Burgher’s baby,To be scared by a scolding name?They may argue, and prate, and order;Go, tell them to save their breath:Then, over the Transvaal border,And gallop for life or death!

Let lawyers and statesmen addleTheir pates over points of law;If sound be our sword, and saddle,And gun-gear, who cares one straw?When men of our own blood pray usTo ride to their kinsfolk’s aid,Not Heaven itself shall stay usFrom the rescue they call a raid.

There are girls in the gold-reef city,There are mothers and children too!And they cry, “Hurry up! for pity!”So what can a brave man do?If even we win, they’ll blame us:If we fail, they will howl and hiss.But there’s many a man lives famousFor daring a wrong like this!’

So we forded and galloped forward,As hard as our beasts could pelt,First eastward, then trending northward,Right over the rolling veldt;Till we came on the Burghers lyingIn a hollow with hills behind,And their bullets came hissing, flying,Like hail on an Arctic wind!

21

Right sweet is the marksman’s rattle,And sweeter the cannon’s roar,But ‘tis bitterly bad to battle,Beleaguered, and one to four.I can tell you, it wasn’t a trifleTo swarm over Krugersdorp glen,As they plied us with round and rifle,And ploughed us, again – and again.

Then we made for the gold-reef city,Retreating, but not in rout. They had called to us “Quick! For pity!”And He said, “They will sally out.They will hear us and come. Who doubts it?”But how if they don’t, what then?“Well, worry no more about it,But fight to the death, like men.”

Not a soul had or supped or slumberedSince the Borderland stream was cleft;But we fought, ever more outnumbered,Till we had not a cartridge left.We’re not very soft or tender,Or given to weep for woe,But it breaks one to have to renderOne’s sword to the strongest foe.

I suppose we were wrong, were madmen,Still I think at the Judgment Day,When God sifts the good from the bad men,There’ll be something more to say.We were wrong, but we aren’t half sorry,And, as one of the baffled band,I would rather have had that forayThan the crushings of all the Rand.

22

[Published in The Times, Saturday 11 January, 1896, p.9].

23

Lines recited by Mrs Beerbohm Tree on the Opening of Her Majesty’s Theatre

Leaving life’s load of dullness at the door,

You come to dwell in Fairyland once more.

Puck, Ariel, Pegasus, imp, fairy, sprite,

All that can lend illusion and delight,

Quick to come forth and frolic as you bid,

Behind that curtain cunningly are hid.

We have the Muses nine, the Graces three,

And all the Passions – under lock and key.

Which would you summon? Laughter, terror, tears?

Call each in turn, and promptly it appears.

Magical medley! Kings upon their throne,

And Queens – though never one to match our own;

Bewildered Innocence, taxed with every crime,

And heroes entering in the nick of time;

Love scorning rank, wealth, ease, for Beauty’s sake,

And Pity sobbing till its heart must break;

Villains triumphant till the final act,

Wit, pathos, humour – everything, in fact,

Romantic, generous, fanciful, ideal:

Romance is only the diviner Real.

Away, the worldling’s mock, the cynic’s sneer!

Imagination holds dominion here,

Whose radiance draws mean mists of lower air

To its own height, to dissipate them there.

Will life ill-pleased, you come not here to see

24

Man as he is, but as you’d have him be,

Tender, yet strong, at infamy aghast,

And woman fond and faithful to the last;

Angels that guard, and Furies that requite,

A heavenly world where everything’s put right.

Should falsehood triumph, still the stage must strive

To keep man’s faith in nobleness alive,

Make him to baser things a little blind,

And with wise hopefulness console mankind.

For this we put on motley to the view,

And travesty ourselves, to comfort you.

Yet there is One, whose venerated name

We humbly borrow, and will never shame;

Who needs no tinsel trappings nor disguise

To shine a Monarch in the whole world’s eyes;

Waits for no prompter for the timely word,

And, when ‘tis uttered, everywhere is heard;

Plays, through sheer goodness, a commanding part,

Speaks from the soul, and acts but from the heart.

Long may she linger, loved, upon the scene,

And long resound the prayer, ‘God save our Gracious Queen.’

[Reprinted from Victoria the Wise (1901), pp.21-23. Under the management of Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Her Majesty’s Theatre was completely rebuilt in the 1890s. It re-opened on 28 April 1897 and became one of the leading London theatres, known for its spectacular productions of Shakespeare and historical dramas – also as the first home of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA), which Tree established. Austin attended the first night, as did the Prince of Wales. Perhaps as a favour to Austin, Tree later put on a production

25

of his final verse drama Flodden Field at the theatre in 1903 – the only public performance of any of Austin’s plays]

Sorrow’s Importunity

When Sorrow first came wailing to my door,

April rehearsed the madrigal of May:

And, as I ne’er had seen her face before,

I kept on singing, and she went her way.

When next came Sorrow, life was winged with scent

Of glistening laurel and full-blossoming bay:

I asked, but understood not, what she meant,

Offered her flowers, and she went her way.

When yet a third time Sorrow came, we met

In the ripe silence of an Autumn day:

I gave her fruit I had gathered, and she ate,

Then seemed unwillingly to go away.

When last came Sorrow, around barn and byre

Wind-carven snow, the Year’s white sepulchre, lay.

‘Come in’ I said, ‘and warm you by the fire.’

And there she sits, and never goes away.

[Reprinted from The Conversion of Winckelmann (1897), pp.88-89]

26

As Dies The Year

The Old Year knocks at the farmhouse door.October, come with your matron gaze,From the fruit you are storing for winter days,And prop him up on the granary floor, Where the straw lies threshed and the corn stands heaped:Let him eat of the bread he reaped;He is feeble and faint, and can work no more.

Weaker he waneth, and weaker yet.November, shower your harvest down,Chestnut, and mast, and acorn brown;For you he laboured, so pay the debt.Make him a pallet – he cannot speak – And a pillow of moss for his pale pinched cheek,With your golden leaves for coverlet.

He is numb to touch, he is deaf to call.December, hither with muffled tread,And gaze on the Year, for the Year is dead,And over him cast a wan white pall.Take down the mattock, and ply the spade,And deep in the clay let his clay be laid,And snowflakes fall at his funeral.

Thus may I die, since it must be,My wage well earned and my work-days done,And the seasons following one by oneTo the slow sweet end that the wise foresee; Fed from the store of my ripened sheaves,Laid to rest on my fallen leaves,And with snow-white souls to weep for me.

[Reprinted from English Lyrics (1890), pp.171-172]

27

Conclusion of The Poet’s Diary: ‘The Poet’ looks back on the 19th century . . .

‘Have you observed,’ I said, ‘that whenever one wants to cite something wise and true, one has to go either to the ancients or to the eighteenth century for it? The succeeding one, the one from which we have just emerged, was, I think, the most vainglorious of all the centuries, characteristically encouraging vainglory in others, and providing people with a number of “Masters” whose teaching is already being questioned, and an Olympus of Divinities that even the blindest now perceive to have been False Gods. All exaggeration, it has often been observed, is followed by reaction, the warm fit by the cold one: and people are now tending towards the other extreme, since suffering from the disillusion that attends excessive enthusiasm, and lament that there are no statesmen, no poets, no philosophers, no painters left. No less than the individual, society has its seasons of pessimism; and it is passing through one at present. On n’est jeune qu’une fois is a concise but scarcely a true aphorism. For my part, I have been old several times, but somehow have always got more or less young again.’

‘And so, my dear Poet,’ said Lamia in her tender way, ‘will it ever be with you. All your life you have been in love with beautiful things; with fair, noble women, with winsome children, hills, forests, streams, open commons, and secluded gardens; with poetry, painting, architecture, sculpture, Spring, Summer, Autumn, aye, and even Winter; with sunlight, moonlight, starlight, all the glorious unbought endowments of Heaven. You will be in love with them to the last; and they who are in love, as you have so often told me, can never be old. Even at the hour of parting and farewell, such may recite what you have called

AN EVENING PRAYER

When daylight dies, the throstle stillSings on, and through deep dusk doth trill Some faint unfinished bars;Then sudden drops into his nest, As though he had forgot the rest, And sleeps beneath the stars.

And when the heavenly HarvesterTo me shall say, ‘In days that were

28

What you did sow, come now and reap,’May I with some late-lingering strainBe my own nurse to my own pain, And sing myself to sleep!’

Books by Alfred Austin

All [except those in smaller type] held by the Leeds Library

1858 Five Years of It

Austin’s first novel, about a young law student, who aspires to be a poet

1861 The Season : A SatireSatirical poem, in the style of Pope, on London society

[1862The Human Tragedy]

First version of Austin’s epic narrative poem, in the style of Byron’s Don Juan

1870 The Poetry of the Period

Collection of critical essays on contemporary poetry, claiming that Browning and Tennyson are over-rated. Browning responded fiercely in his poem Pachiarotto (1876), lampooning Austin as ‘Banjo-Byron’ and ridiculing him for his short stature.

1871 The Golden Age: A SatireSatirical poem on contemporary society

[1872Interludes] Austin’s first volume of shorter lyrical and occasional poems

1873 Rome or DeathAn extension of The Human Tragedy, in which the main characters are caught up in Garibaldi’s failed campaign to annexe the Papal States to Italy in 1867

1874 The Tower of Babel Austin’s first verse drama, based on the Bible story

[1876 Tory Horrors]

Political pamphlet, responding to Gladstone’s Bulgarian Horrors29

30

1876 The Human TragedyA longer version of the 1862 poem, incorporating Madonna’s Child, Rome or Death, and a final Canto in which the characters are caught up in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War (1870) and the end of the Paris Commune (1871)

1881 Savonarola: A TragedyVerse drama set in Renaissance Florence

1882 Soliloquies in SongNarrative and lyric poems

1885 At the Gate of the ConventNarrative and lyric poems

[1885 The Human Tragedy]

Final version of the 1862/1876 poem, revised and shortened, with long introductory essay

1887 Prince Lucifer Verse drama

1889 Love’s WidowhoodNarrative and lyric poems

1890 English LyricsA collection based on Austin’s previous volumes of lyric poems, edited with an introduction by William Watson – this volume helped to establish Austin’s credentials as a candidate for laureate

1892 Fortunatus the PessimistVerse drama

1894 The Garden that I LoveFirst in a series of prose works, containing reflections on gardening and other topics, and introducing the four characters of Lamia, Veronica, ‘The Poet’ and the narrator; based on Austin’s household and his garden at Swinford Old Manor, Kent. The popular success of this series probably also helped towards Austin’s appointment in 1896.

1895 In Veronica’s GardenSequel to The Garden that I Love

31

1896 England’s DarlingVerse drama about Alfred the Great’s victory over the Danes

1897 The Conversion of WinckelmannNarrative and lyric poems

1898 Lamia’s Winter QuartersThe characters from The Garden that I Love holiday in Italy

1901 Victoria the WiseA collection of Austin’s poems addressed to or celebrating Queen Victoria

1902 Haunts of Ancient PeaceThe characters from The Garden the I Love travel round rural England

1902 A Tale of True LoveNarrative and lyric poems

1903 Flodden FieldVerse drama about the Battle of Flodden. This was the only one of Austin’s plays to be briefly staged, at His Majesty’s Theatre in The Haymarket, London, in June 1903.

1904 The Poet’s Diary: edited by LamiaContinuation of The Garden that I Love series, but more about Austin’s memoirs of Italy than his garden – a kind of rehearsal for his Autobiography. Lamia had become such a popular character by this time that the book was published without Austin’s name appearing on the book.

1906 The Door of Humility Narrative poem in four-line stanzas, on the tension between love and religious faith

1910 The Bridling of Pegasus: Prose Papers on Poetry

Collection of critical essays on literary topics

1911 The Autobiography of Alfred Austin, Poet Laureate, 1835-1910.

32

Two-volume autobiography, considerably padded out by the inclusion of many of Austin’s special correspondent reports for The Standard from Rome, Paris and Berlin in 1870-1871.

33