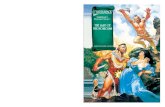

The Last of the Mohicans c. 1919

description

Transcript of The Last of the Mohicans c. 1919

The Last of the Mohicansc. 1919

N. C. Wyeth

[1882 – 1945]

Newell Converse Wyeth c.1920

Newell Convers Wyeth (October 22, 1882 – October 19, 1945), known as N.C. Wyeth, was an American artist and illustrator.

Wyeth in his studio, 1903 or 1904

Newell Convers Wyeth was born in Needham, Massachusetts on October 22, 1882. His grandparents were Swiss immigrants and N.C. himself grew up on a farm surrounded by immigrant values and customs.

He attended Mechanic Arts High School in Boston through May 1899, concentrating on drafting.

With his mother's support he transferred to Massachusetts Normal Art School, and there instructor Richard Andrews urged him toward illustration.

His mother, Henriette Zirngiebel Wyeth, encouraged his artistic talent while conversely, his father Andrew Newell Wyeth II, called an artist's life "shiftless, almost criminal."

When two of his friends were accepted to Howard Pyle's School of Art in Wilmington, Delaware and Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, Wyeth was invited to try to join them in 1902.

Howard Pyle was the "father" of American illustration, and Wyeth immediately meshed with his methods and ideals.

Pyle’s approach included excursions to historical sites and impromptu dramas using props and costumes, meant to stimulate imagination, emotion, atmosphere, and the observation of humans in action—all necessities for his style of illustration.

Pyle stressed historical accuracy and tinged it with a romantic aura.

But where Pyle painted in exquisite detail, Wyeth veered toward looser, quicker strokes and relied on ominous shadows and moody backgrounds.

Wyeth’s exuberant personality and talent made him a standout student.

A robust, powerfully built young man with strangely delicate hands, he ate a lot less than his size implied.

He admired great literature, music, and drama, and he enjoyed spirited conversation.

Only five months after starting Pyle’s art school, A painting of a bucking bronco for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on February 21, 1903 was Wyeth's first commission as an illustrator.

That year he described his work as "true, solid American subjects–nothing foreign about them." Wyeth found early success producing illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post.

It was a spectacular accomplishment for the 21-year-old Wyeth, after just a few months under Pyle’s tutelage.

In 1904, the same magazine commissioned him to illustrate a Western story, and Pyle urged Wyeth to go West to acquire direct knowledge, much as Zane Grey had done for his Western novels.

In Colorado, he worked as a cowboy alongside the professional "punchers," moving cattle and doing ranch chores.

He visited the Navajo in Arizona and gained an understanding of Native American culture.

When his money was stolen, he worked as a mail carrier on horseback to gain back needed funds.

He wrote home, "The life is wonderful, strange—the fascination of it clutches me like some unseen animal—it seems to whisper, 'Come back, you belong here, this is your real home.' "

On a second trip two years later, he collected

information on mining and brought home costumes and artifacts, including cowboy and Indian clothing.

His early trips to the western United States inspired a period of images of cowboys and Native Americans that dramatized the Old West.

His depictions of Native Americans tended to be sympathetic, showing them in harmony with their environment, as demonstrated by In the Crystal Depths (1906).

His three trips between 1904 and 1906 to the western United States inspired a period which produced illustrations of cowboys and Native Americans that dramatized the Old West.

Wyeth's travels were inspired by those of renowned American West artist, Frederic Remington, whom he had admired as a child.

Wyeth's pictures of Native Americans from this period show their unique and solitary relationship to nature.

One of his most popular was of a woodland Indian, titled, The Moose Call, painted in 1904.

Pictures from the "Indian in His Solitude Series" were printed in a 1907 issue of Outing magazine.

c.1907 In the Crystal Depths

Winter c. 1909

The Hunter c. 1907

N.C. Wyeth in his Western “Rig," 1904

Upon returning to Chadds Ford, he painted a series of farm scenes for Scribner's, finding the landscape less dramatic than that of the West but nonetheless a rich environment for his art: “Everything lies in its subtleties, everything is so gentle and simple, so unaffected.”

His painting Mowing (1907), not done for illustration, was among the most successful images of rural life, rivaling Winslow Homer's great scenes of Americana

Howard Pyle In 1894 he began teaching illustration at the

Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry in Philadelphia (now Drexel University),

After 1900 he founded his own school of art and illustration called the Howard Pyle School of Illustration Art.

The term the Brandywine School was later applied to the illustration artists and Wyeth family artists of the Brandywine region (later called the Brandywine School)

Pyle is considered the Father of Illustration.

Pyle was one of the country's most renowned illustrators.

Wyeth was the star pupil of artist Howard Pyle and became one of America's greatest illustrators.

Howard Pyle His 1883 classic The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood remains in print to this day, and his other books, frequently with medieval European settings, include a four-volume set on King Arthur that cemented his reputation.

He wrote an original novel, Otto of the Silver Hand, in 1888.

He also illustrated historical and adventure stories for periodicals such as Harper's Weekly and St. Nicholas Magazine.

His novel Men of Iron was made into a movie in 1954, The Black Shield of Falworth.

Howard Pyle (March 5, 1853 – November 9, 1911)

Pirates fight over treasure Howard Pyle

illustration

While studying with Pyle, Wyeth met his future wife, Carolyn Bockius, whose family lived three blocks from the Pyle Studios on Gilpin Avenue.

According to Wyeth's biographer, "By all accounts she was the prettiest girl in Wilmington."

N.C. Wyeth

In 1906, Wyeth married Carolyn Brenneman Bockius of Wilmington.

The couple lived for a short time in the city, but moved in 1908 to Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, 10 miles north of Wilmington along the Brandywine Creek.

Chadds Ford had been the site of Pyle's summer school, and the rolling hills and sycamore trees of the Brandywine Valley had already exerted a profound influence on Wyeth, subduing his enthusiasm for the rough and tumble west.

In 1911, the Wyeths purchased 18 acres of property in Chadds Ford, not far from a Revolutionary War battlefield.

The proximity appealed to the artist's abiding love of history.

Immediately the Wyeths set about to build a house and studio.

They would raise five talented children on this property.

The valley landscape would become almost sacred to the displaced New England

N.C. Wyeth created a stimulating household for his talented children Andrew Wyeth, Henriette Wyeth Hurd, Carolyn Wyeth, Ann Wyeth McCoy, and Nathaniel C. Wyeth.

Wyeth was very sociable, and frequent visitors included F. Scott Fitzgerald, Joseph Hergesheimer, Hugh Walpole, Lillian Gish, and John Gilbert.

According to Andrew, who spent the most time with his father on account of his sickly childhood, N.C. was a strict but patient father who did not talk down to his children.

His hard work as an illustrator gave his family the financial freedom to follow their own artistic and scientific pursuits. Andrew went on to become one of the foremost American artists of the second half of the 20th century, and both Henriette and Carolyn became artists also; Ann became an artist and composer. Nathaniel became an engineer for DuPont and worked on the team that invented the plastic soda bottle. Henriette and Ann married two of N.C.'s protégés, Peter Hurd and John W. McCoy.

N.C. Wyeth is the grandfather of artist Jamie Wyeth and musician Howard Wyeth.

N.C. Wyeth The Studio

Chadds Ford Landscape-July 1909

By now, he had left Pyle, and commissions were coming in quickly.

His hope had been that he would make enough money with his illustrations to be able to afford the luxury of painting what he wanted; but as his family and income grew, he found it difficult to break from illustration.

In 1911, the publishing house of Charles Scribner's Sons engaged Wyeth to illustrate Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island, his first commission in Scribner's popular series of classic stories.

The 17 paintings that make up the set are masterpieces of American illustration.

One More Step, Mr. Hands by N.C. Wyeth, 1911, for

Treasure Island

Their size and scale, unusual in illustrations

of the period, give the paintings a heroic quality that is apparent even in the greatly reduced reproductions.

Within the set of illustrations, Wyeth brilliantly mixed subject matter.

Action and character study are united in each painting to further the narrative beyond the text.

Treasure Island -The Hostage

In every canvas, Wyeth's superb sense of color and his ability to mix painterly passages with authentic detail prove him a master of the art.

Complex compositions and his skillful use of intense light contrasted with deep shadow contribute to a palpable dramatic tension inherent in the paintings and not dependent on the text.

These pictures made the Wyeth-illustrated edition of Treasure Island a favorite of generations of readers.

The success of Treasure Island insured Wyeth a long career with Scribner's, illustrating in succeeding years many classic stories.

Wyeth’s most famous titles Kidnapped (1913), The Black Arrow (1916), The Boy's King Arthur (1917), The Mysterious Island (1918), The Last of the Mohicans (1919), The Deerslayer (1925), The Yearling (1939).

Robin Hood

He also created illustrations for other publishers, for books Robin Hood (Philadelphia: David McKay,

1917); Robinson Crusoe (New York:

Cosmopolitan, 1920); Rip Van Winkle (Philadelphia: David

McKay, 1921); Men of Concord (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin,

1936); Trending Into Maine (Boston: Little, Brown,

1938).

During the Golden Age of Illustration

During his lifetime, Wyeth created over 3,000 paintings and illustrated 112 books

25 of them for Scribner's, which is the work for which he is best-known.

Another source creates him with nearly 4,000 works over a period from 1903 to 1945.

N. C. Weyth

The Last of the Mohicans

An American adventure tale by James

Fenimore Cooper, became an instant best-seller when it was published in 1826.

Its popularity continued, and by 1919, when N. C. Wyeth illustrated a new, deluxe edition of the book, Cooper’s story had become a fixture in American boyhood.

It has since fallen out of fashion, but its importance to American literature is firmly established:

the protagonist, Natty Bumppo (called Hawkeye), a white scout raised by American Indians, is the first of many enterprising pioneer heroes to overcome the perils of the frontier.

And even though The Last of the Mohicans had been illustrated before, Wyeth’s pictures did much to create an enduring image of the American Indian as a “noble savage.”

George Catlin: Boy Chief, Ojibbeway

Seminole Chief Osceola

Cover Illustration

Wyeth’s teacher Howard Pyle had taught him to work only from experience.

To prepare for The Last of the Mohicans,

Wyeth made two trips to the Lake George region of New York, where the novel is set.

New York State

Lake George, NY

Lake George, New York

Lake George, NY

He tramped through the woods and cooked over an open fire to gain an understanding of the wilderness and to allow the features of the landscape to impress themselves on his mind.

Inspired by the crystal-clear summer atmosphere of the Adirondacks, Wyeth bathed his pictures in sky-blue tones that lend an air of tranquility to a violent and tragic story.

It was not possible for Wyeth to make the same careful study of the American Indians who figured in the novel.

Cooper himself had confessed that when he wrote The Last of the Mohicans, he had never spent time among American Indians, and that most of what he knew of their lives and customs had been gleaned from books or from stories passed down from his father.

The novel takes place in 1757, during the French and Indian War,( or the 7 years War) when the British and French fought over land that had long been home to Eastern Woodlands tribes.

Wyeth was yet another generation removed from those historical events;

like most Americans of his time, he possessed only the vaguest understanding of the original American peoples.

Describing the clothing

He wears a rough cloth or animal skin skirt Leather strap across his chest A thin belt holding his knife and tomahawk An arm band A feather in his hair Body paint

How does his clothing tell who he is?

In the early 1900’s, this was how most Americans thought American Indians might have dressed.

The weapons suggest that he is a warrior without a gun.

How does Wyeth emphasize the form of this warrior?

Wyeth makes him large Dark against a light background Outlines him in black Surrounds him with a cloud that echoes his

shape.

Although rooted in history,

The Last of the Mohicans was

Cooper’s invention.

To criticism that the characters were unrealistic, Cooper replied that the novel was intended only to evoke the past.

The illustrator took the artist’s poetic license one step further.

This image, which appears on the cover of

the book, was apparently inspired by Cooper’s character Uncas, Hawkeye’s faithful friend and one of the last Mohicans:

“At a little distance in advance

stood Uncas, his whole person thrown powerfully into view. The travelers anxiously regarded the upright, flexible figure of the young Mohican, graceful and unrestrained in the attitudes and movements of nature.”

Cooper stresses the American Indian’s identification with the natural world

Wyeth accordingly portrays Uncas in harmony with the landscape, framed by a formation of clouds.

He retains other elements of Cooper’s description as well, notably the account of Uncas’s

dark, glancing, fearful eye, alike terrible and calm; the bold outline of his high haughty features, pure in their native red…the dignified elevation of his receding forehead, together with all the finest proportions of a noble head, bared to the generous scalping tuft.

To capture the commanding presence of the character, Wyeth adopted a low viewpoint, so that the powerful body of Uncas appears larger than life as he advances right to the edge of the canvas, the unspoiled American landscape spread out below and behind him.

What does Wyeth suggest about the health and character of this American Indian? Wyeth shows him to be strong, healthy,

muscular, and standing straight. The intense stare of his eyes, his downturned

mouth, and the set of his shoulders suggest that he is determined alert, serious, and ready to act.

Look at the cloud surrounding the character… The cloud gives him a special

character.

It acts as his nimbus or aura.

In other respects, Wyeth alters Cooper’s portrayal of Uncas.

Differences

The Uncas whom Wyeth pictures is bare-chested, covered in war paint, and crowned with a feather.

Cooper points out in the novel that Uncas’s “person was more than usually screened by a green and fringed hunting shirt, like that of the white man.”

Differences

Even though the plot of The Last of the Mohicans depends upon the American Indians

carrying muskets alongside European soldiers,

Wyeth portrays Uncas with a dagger, a tomahawk, and a bow and arrow—weapons of pre-colonial warfare and the customary attributes of an Indian brave.

Differences

While Cooper suggests the complexity of the character,

Wyeth generalizes and romanticizes the Indian hero’s appearance.

In this way, Wyeth conforms to his era’s understanding of American Indians, which was tightly bound to the ideal of an untamed wilderness.

Despite his fame as an illustrator,

Wyeth yearned to be known as a painter.

The distinction between painting and illustration was an important one, with illustration carrying a pejorative connotation that Wyeth felt keenly all his life.

Even though the commissioned work earned him income to support his family, he tried to escape the confines of textual limitations with personal paintings that included landscapes, still lifes, and portraits.

N.C. Wyeth, Still Life with Onions

By 1914, Wyeth loathed the commercialism upon which he became dependent, and for the rest of his life, he battled internally over his capitulation, accusing himself of having “*&@#$ myself with the accursed success in skin-deep pictures and illustrations.”

He complained of money men "who want to buy me piecemeal" and that "an illustration must be made practical, not only in its dramatic statement, but it must be a thing that will adapt itself to the engravers' and printers' limitations.

This fact alone kills that underlying inspiration to create thought.

Instead of expressing that inner feeling, you express the outward thought… or imitation of that feeling."

Wyeth's works also contains religious paintings. In 1923 he was commissioned by the Unitarian Layman's League to do a series of paintings titled "The Parables of Jesus.“

His most magnificent religious work is considered his triptych (consisting of three hinged panels) painted for the Chapel of the Holy Spirit at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C.

Jesus, surrounded by a host of heavenly angels, seems to be welcoming his believers: "Come Unto Me, All Ye that Labor and Are Heavy Laden, and I Will Give You Rest."

Wyeth also did posters, calendars, and advertisements for clients such as Lucky Strike, Cream of Wheat, and Coca-Cola,

He did paintings of Beethoven, Wagner, and Liszt for Steinway & Sons.

N.C. Wyeth, American Red Cross Poster

He painted murals of historical and allegorical subjects for the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, the Westtown School, the First National Bank of Boston, the Hotel Roosevelt, the Franklin Savings Bank, the National Geographic Society, and other public and private buildings.

During both World Wars, he contributed patriotic images to government and private agencies.

N.C. Wyeth at work on mural

One of largest single murals in the United States, painted in 1932, is Apotheosis of the Family, which contains likenesses of Wyeth's own family members.

It is 19 feet high by 60 feet long and mounted in five sections. It spans the entire south wall of the Wilmington Savings Fund Society Building in Wilmington, Delaware.

Apotheosis of the Family

Wyeth worked rapidly and experimented constantly, often working on a larger scale than necessary, befitting his energetic and grand vision, which often harked back to his ancestral past.

He could conceive, sketch out, and paint a large painting in as little as three hours.

By the 1930s, he restored an old captain’s house in Port Clyde, Maine, named "Eight Bells" after a Winslow Homer painting, and took his family there for summers, where he painted primarily seascapes.

Museums started to purchase his paintings, and by 1941, he was elected to the National Academy and exhibited on a regular basis.

In 1945, N.C. Wyeth and his grandson (Nathaniel C. Wyeth's son) died in an accident at a railway crossing near his Chadds Ford home.

At the time of his death, Wyeth was working on an ambitious series of murals for the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company depicting the Pilgrims at Plymouth, a series completed by Andrew Wyeth and John McCoy.

His non-illustrative portrait and landscape paintings changed dramatically in style throughout his life as he experimented first with impressionism in the 1910s.

By the 1930s veering to the realistic American regionalism of Thomas Hart Benton and Grant Wood, painting with thin oils and occasionally, egg tempera.

From lyrical landscapes in an Impressionist style to powerful portraits of fishermen that recall the work of the American Regionalist artists, Wyeth experimented throughout his career with a wide variety of subjects and styles.

However, he never did attain the personal satisfaction or public recognition that he sought.

In a 2002 episode of the TV show Antiques Roadshow, a Wyeth painting in excellent condition, believed to be titled When He Comes He Shall Rule the World, was appraised to be worth as much as $250,000.

The painting was done to illustrate a story in Harper's Monthly magazine called The Lost Boy, by Henry van Dyke.

Ladies' Home Journal, "The Son Of Man" (1927)

Scribner's, "The Sheriff" (1912)

(1914)

McCall's, "The Midnight Revel" (1924)

Ladies' Home Journal, cover (1924)

Scribner's, "Lascar" (1907)

Ladies' Home Journal, "The Legend Of Kogal And Azin" (1927)

Collier's, "Balloon Attack" (1919)

Printer's Ink Monthly (1934)

Coca-Cola, "Through All The Years From 1886" (1938)

Coca-Cola, "Get The Feel Of Wholesome Refershment" (1936)

Coca-Cola, "It's The Refreshing Thing To Do" (1937)

Scribner's, "Football" (1910)

Aunt Jemima (1920)

Scribner's, "Aide De Camp" (1907)

Scribner's, "The Stable At The Inn" (1912)

New Story Magazine (1914)

Scribner's, "The Moose Hunter, The Midnight Call" (1912)

Scribner's, "The Balloon Corps" (1908)

Paul Jones Whiskies (1935)

Paul Jones Whiskies (1935)

The Red Cross Magazine (1919)

I shall never forget the sight. It was like a great green

sea., 1918,

Scottish Chiefs

Woman's Day, "The Yearling" (1947)

Guide and Hunter, 1925

John Paul Jones

John Alden and Pricillia

Treasure Island

![Cooper, James F. ''The last of the Mohicans''-En-Sp James F. ''The last … · The Last of the Mohicans [1757] by James F. Cooper [Etext #940] 1997 INTRODUCTION It is believed that](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/5e9ec746efa12b17760223a0/cooper-james-f-the-last-of-the-mohicans-en-sp-james-f-the-last-the-last.jpg)