The Greening of Cincinnati: Adolph Strauch's Legacy in...

Transcript of The Greening of Cincinnati: Adolph Strauch's Legacy in...

20

The Greening ofCincinnati: AdolphStrauch's Legacy inPark Design

Queen City Heritage

Blanche Linden-Ward

In 1852 fate proved permanently beneficialto the making of picturesque landscapes in Cincinnati andto the history of American landscape design.The thirty-two-year-old Prussian landscape gardener, Adolph Strauch(1822-1883) missed his train connection in Cincinnati enroute from the Texas frontier to see Niagara Falls. Strauchhad not intended to visit the "Metropolis of the West."But temporarily stranded in the strange city, he recalledhaving met a local resident, Robert Bonner Bowler, whoseappreciation for fine picturesque designed landscapes, thejar din anjjlais, Strauch had helped heighten in 1851 whileguiding Americans through the London Crystal PalaceExhibition and various notable English gardens. Strauchretrieved Bowler's calling card from his pockets and con-tacted the civic leader, who greeted him warmly andseized the opportunity not only to welcome the unexpect-ed visitor to Cincinnati but to persuade Strauch to cancelthe rest of his travel plans.

Wealthy Cincinnatians immediately recog-nized Strauch as a world-class designer and were intent onnot losing him. Strauch had impressive credentials thatsuggested large possibilities for application of his talents inCincinnati. He began his career as protege of PrinceHerman von Piickler-Muskau, the great European parkreformer, a benevolent aristocrat who transformed hisSilesian estate around the town of Muskau into landscapedgrounds that later served as "precedents for metropolitanpark systems" in Europe and America. Puckler counseledthe young Strauch to further his horticultural expertise atthe Schoenbrunn and Laxenburg Hapsburg imperial gar-dens and in England in the great eighteenth-century pas-toral gardens.1

To attach Strauch to Cincinnati, Bowler, hiswell-placed friends, and other leading citizens, founders ofthe Cincinnati Horticultural Society who aspired to culti-vate a taste for nature, literally and figuratively, gaveStrauch private commissions to design the grounds of

their suburban estates in the new "Eden of the Cincinnatiaristocracy," the "romantic village" of Clifton on the hillsnorth of their burgeoning city. Strauch designed theirestates to create the impression of a large, rambling, singleproperty by eliminating fences and other visible lines andby sculpting sweeping lawns punctuated by carefullyplaced bosks of trees framing palatial homes and definingdistant views. He gave the new suburb a unified pastorallandscape preceded in America only by Cincinnati's own

Glendale (1851), New Jersey's Llewellyn Park (1853), andLake Forest, Illinois (1857). In 1870 one observer described"the present perfect state" of Clifton's development basedon years of labor directed by Strauch to create "the gentleslopes, the gradual rise and fall of the surface. . . .Deepravines have been filled, elevations cut down, and inequali-ties reconciled." Strauch also helped his horticulturist

Blanche Linden-Ward, a visit-ing scholar in AmericanStudies at Tufts University,received her Ph. D. in Historyof American Civilization fromHarvard University.

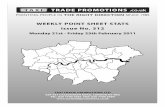

In 1870 the park commission-ers hired Adolph Strauch asParks Superintendent.Strauch, who had served aslandscape gardener andsuperintendent of SpringGrove Cemetery since the

1850s, continued as thecemetery's superintendent.(Adolph Strauch, CHS PrintedWorks Collection)

Spring 1993 The Greening of Cincinnati 21

clients assemble "a valuable collection of evergreens, gath-ered from various countries of the globe" as well as manyrare shade and ornamental trees.2

At Bowler's "Mount Storm" property onLafayette Avenue, Strauch created an English park-likelandscape complete with a lake, waterfall, and neoclassical"eyecatcher" copied after the Temple of Love in the PetiteTrianon at Versailles. It crowned a hill atop a reservoir thatsupplied water to the horticulturist's extensive greenhousesand created a fine setting for the 1860 reception of LordRenfew, Edward Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII,and for Emperor Dom Pedro of Brazil. Strauch alsoworked on Robert Buchanan's forty-three-acre"Greenhills" (1843), Henry Probasco's thirty-acre"Oakwood" (1859-66), George Krug Schoenberger's forty-seven-acre "Scarlet Oaks" (1867-71), and George W. NefFs"The Windings" (1869). At these estates, reached by wind-ing avenues and drives through the undulating topogra-phy, themselves providing "a sequence of carefullydesigned, gradually unfolding views" for those arriving bycarriage, Strauch maximized dramatic distant vistas overthe Millcreek Valley with "its varied spectacle of village andfarm, cultivated fields and distant forest-covered hill," apanorama to the west which these gentlemen had alreadypreserved by the founding of Spring Grove Cemetery.3

These men were especially anxious to takeStrauch to Spring Grove, Cincinnati's "rural" cemeterycreated in 1845 to rival the nationally famous prototypes ofBoston's Mount Auburn (1831) and New York's Green-Wood (1838). As directors of the cemetery, Buchanan andProbasco expected to hear praise for their romantic funer-ary landscape designed by local architect Howard Daniels.Instead, Strauch gave them perceptive, frank, and incisivecriticisms, saying that parts of the cemetery had in less thana decade taken on the cluttered and undesirable "appear-ance of a marble yard where [monuments] are for sale."Strauch told them that in 1843 the great Scottish landscapetheorist John Claudius Loudon had declared that a ceme-tery "properly designed, laid out, ornamented with mau-soleums, tombs, columns, urns, tastefully planted withappropriate trees and shrubs, and the whole properly kept,might become a school of instruction" in elements of land-scape design as well as a place of "neatness, order, and highkeeping" that elevates public taste and serves as a measureof civilization's quality. Impressed by these ideas,Buchanan and his friends hired Strauch as Spring Grove'slandscape gardener in October 1854, and in 1859 appointedhim superintendent. Strauch promised to unify the land-

scape aesthetics through "scientific management" and toestablish "the aesthetics of the beautiful" as described bythe English theorist Edmund Burke.4

Strauch called his entirely innovative reformthe "landscape lawn plan." There were no exact prece-dents in terms of aesthetics intended to create a park-likefunerary landscape; even Loudon had not been able to cre-ate such a pastoral ideal in a cemetery. Strauch aspired tocreate a synthesis of the "picturesque" and the "beautiful"through a series of regulations as well as design of thegrounds. "A rural Cemetery," he believed, "should formthe most interesting of all places for contemplative recre-ation; and everything in it should be tasteful, classical, andpoetical."5

He transformed swampy areas around theoriginal cemetery core into five acres of spring-fed pic-turesque lakes. By the 1860s Strauch had made SpringGrove an attractive promenade, a 412 acre "arboretum"adorned by fine sculpture, architecture, and waterfowl,making it not only the largest cemetery in the world butone that attracted international recognition of his land-scape "artistry" and horticultural expertise. By 1875 he hadexpanded the grounds to 594 acres, including large areas ofwoodland preserve. Spring Grove attracted national atten-tion in subsequent decades as leaders of many existing andnew cemeteries accepted his aesthetic reforms for creationand maintenance of a park-like appearance for funerarylandscapes. Frederick Law Olmsted proclaimed SpringGrove "the best [cemetery in the United States] from alandscape gardening point of view" shortly after he haddiscovered the art of landscape design.6

Spring Grove was Cincinnati's first park-likeopen space, run by a nonprofit corporation but open tothe public with limited restrictions. Under Strauch, itbecame a major urban amenity, used by locals and visitorsas a "pleasure ground" and touted by boosters as "a beau-tiful park for the living." By 1860 under Strauch's influenceon suburb and cemetery design, one Philadelphia horticul-turist judged Cincinnati "a center for correct taste in ruralarchitecture, landscape gardening, and the various arts thatare associated with suburban and rural life . . . a long wayin advance of Philadelphia, New York, or Boston."7

Although Cincinnati was still very young,barely six decades from its urban frontier beginnings, rapiddevelopment left little other room for perserving, creating,or cultivating green public open spaces — spaces to reflectwhat the internationally renowned landscape architectAndrew Jackson Downing had recently termed "rural art

22

and rural taste." Through his popular magazine TheHorticulturist, Downing spread the vogue for "pic-turesque" and "beautiful" landscapes in suburban loca-tions; and he was the first to call for creations of naturalis-tic public parks of similar design in the middle of the denseurban fabric. Such landscapes were proclaimed important,civilizing forces as antidotes and counterpoints to thecrowded and disorderly physical environments characteris-tic of contemporary urbanization. As in other antebellumcities, urban real estate development had proceeded at ahaphazard, unregulated, break-neck pace, leaving littleroom for the sort of green open spaces that were termedthe "lungs" of the city, breathing room for burgeoningpopulations.8

Generally, urban populations relied on theirnew "rural" cemeteries as antidotes to the crowding, over-development, and pollution of antebellum cities. Indeed,the example of landscape design and popularity of thesecemeteries inspired the mid-century public park move-ment. Downing lobbied in 1849 for the creation of publiclandscapes aesthetically similar to the naturalistic cemeter-ies. He wrote President Millard Filmore about the desir-ability of turning Washington's Mall into a picturesquelandscape like those of Mount Auburn and Spring Grove:"At the present moment the United States, while theyhave no public parks, are acknowledged to possess the

Queen City Heritage

finest rural cemeteries in the world."9

Downing's efforts resulted in funding for a683 acre Central Park in New York City. Indeed, ifDowning had not died at age thirty-six in a steamboataccident on the Hudson River in 1852, he undoubtedlywould have designed Central Park along with his architectpartner Calvert Vaux. Instead, Vaux asked the writerFrederick Law Olmsted, inexperienced in landscape designbut newly appointed to superintend the park construction,to join him in the design competition. Their GreenswardPlan (1858) won the competition, followed among the fourfinalists by the entry of former Cincinnatian HowardDaniels, by then experienced in designing a dozen "rural"cemeteries after laying out Spring Grove. The city ofBaltimore hired Daniels in 1860 to design its new 600-acreDruid Hill Park, preserving a beautiful old section ofwoodlands north of the central city.10

The park-making impulse rapidly spread toother cities in the 1860s as urban boosters proclaimedgreen open spaces necessary public amenities and civilizingforces. The civic elite also realized that parks increasedadjacent real estate values and salvaged parcels of land thatmight be or become unsightly nuisances. Urbanists like theNew York art critic Clarence Cook proselytized for parks,also citing the precedents of "rural" cemeteries. In 1869Cook wrote, "These cemeteries . . . became famous over

By the 1860s Strauch had international recognition formade Spring Grove Cemetery his landscape artistry andan attractive promenade, a412 acre "arboretum"adorned by fine sculpture,architecture, and waterfowl,and had attracted

horticulture expertise. (CHSPhotograph Collection)

Spring 1993 The Greening of Cincinnati 23

the whole country and thousands of people visited themannually. They were among the chief attractions of thecities to which they belonged. No stranger visited . . .these cities for pleasure or observation who was not takento the cemeteries . . . . [that] were all the rage, and sodeeply was the want felt which they supplied, and so trulybeautiful were they in themselves, that it was not to bewondered at if people were slow to perceive a certainincongruity between a graveyard and a place of recre-ation." People were simply "glad to get fresh air, and asight of grass and trees and flowers with, now and then, apretty piece of sculpture, to say nothing of the drive to allthis beauty, and back again, without considering toodeeply whether it might not be better to have it all with-out the graves." As in other cities, the example of SpringGrove in Cincinnati suggested formation of the first parks,and Strauch applied his landscape skills to the latter as tothe former.11

After the distraction of the Civil War, theurban public park movement swept the nation. CentralPark was completed, and Brooklyn commissioned Vauxand Olmsted to create the 550-acre Prospect Park (1865-1873) on land set aside in the 1850s around a municipalreservoir. Beginning in 1867 Philadelphia laid outFairmount Park, 2,740 acres of grounds overlooking theSchuylkill River that were preserved from other develop-ment that might have imperiled the public water supply.H. W. S. Cleveland laid out Milwaukee's Juneau Park in1873. Earlier Strauch had traveled to eastern cities and toEurope to inspect and gather information on other ceme-teries as well as public parks, zoological gardens, and col-leges campuses, models that could be used for future pro-jects. Strauch used his position as Spring GroveSuperintendent to advocate creation of other pastorallandscapes in the Cincinnati area.12

Cincinnati was in dire need of public parks.In 1860 "an average of 30,000 people lived in each squaremile [of the central city], making Cincinnati one of themost densely populated cities in America." By 1875 abouta quarter million people crowded the "city proper," adense population in about twenty-four square miles in theurban basin, hemmed in by an amphitheatre of hills toform "the compactest city in the United States." Thedecade after the Civil War was an era of immense andintense transition in the once dominant "Metropolis of theWest," as new railroads permitted Chicago to usurp itsregional dominance as an entrepot.13

The Queen City was slower than other cities

to create major public parks for these reasons and becauseof political wrangling and journalistic criticism of the"park scheme" to be undertaken under public auspices.Cincinnatians, like most urban Americans, were accus-tomed to benefiting from development of "public" ameni-ties under private auspices. In 1867 some of the civic-minded suggested that the work of turning the Mill Creekbottom into a "pleasure ground" be undertaken by thecity itself, a project that would have been unprecedented.Indeed, the Spring Grove Cemetery corporation coveredmost of the costs for developing a parkway, Spring GroveAvenue, running north from the urban core up theMillcreek Valley to the cemetery. The project involvedconsiderable planting of trees and filling of the banks notonly to beautify the approach to the cemetery but to pre-vent injury to the avenue from flooding. Spring Grove'smanagement also wanted "to convert the rough hillsideoverlooking the cemetery [and near Trustees' new Cliftonhomes] into a thing of beauty, utilizing the splendid cas-cade formed by the wasteway of the Miami Canal," mak-ing lakes, water jets, and fountains like those Strauch hadadded within the cemetery grounds. Spring Grove trusteeshoped "to prevent hog-pens, distilleries, starch factories,slaughterhouses, bone-boiling establishments, or stink fac-tories of any kind" from appearing in the parkway stripthey fashioned and wanted to preserve as a corridorbetween the city and their cemetery. They also con-tributed to the building of roads adjacent to the cemeteryby helping in the construction of Mitchell Avenue linkingthe cemetery to Avondale and Clifton, and GroesbeckAvenue from College Hill to the north, and in the build-ing of the portion of Winton Road along Spring Grove'sboundaries. M

The first successful crusade to create largerpublic parks in Cincinnati began when a newspaper articlein 1870 declared that parks "are economical institutions forany city:"

They serve a multitude of purposes. Theirestablishment gives a metropolitan character to a place,greatly increasing its importance abroad. They tend toenhance the value of real estate, not only in their immediatevicinity, but everywhere within the corporation limits. Thisindirectly, and directly too, augments the prosperity of theplace, as it gives an imputus to every kind of business, byinviting capitalists, business men, and manufacturers fromother places to settle among us and invest their money. . . .They tend to enlarge the ideas of the people to develop withinthem a broader and higher comprehension of the beauties of

24 Queen City Heritage

nature, a more refined taste and higher appreciation of art,and, above all, to chasten, purity, and enlarge the moralnature; to render the mind clear, to strengthen and invigo-rate the body, and, in short, to give, tone, activity, power andbeauty to the entire being, moral, spiritual, mental, andphysical.Park proponents kept up the agitation in 1871, declaring,"Parks are among the improvements of all modern cities.They are a part of the great whole which makes a cityinteresting to its inhabitants, to the strangers who come toit for residence or business. They are thoughtful provisionsfor the happiness of the people for centuries to come. Theypromote health and good order of the population, and nocity can well neglect them."15

Through the late 1860s and the early 1870s,Cincinnati newspapers featured articles praising publicparks in other major cities, especially in Europe — NewYork's Central Park, the new Buttes-Chaumont andMontsouris in Paris, the Volksgarten in Vienna. Voicesfavoring similar ventures in Cincinnati hoped to stir boost-erism through competition, to instill a desire for parks likethose in other world class cities. Other sites in the metro-politan area had been considered for parks. In 1867 W. F.Hurlbert proposed that the Common Council purchaseJudge D. H. Este's property to the north of the city, pastSpring Grove Avenue and the junction of the Hamiltonand Dayton as well as the Marietta and CincinnatiRailroads. A large omnibus took an entourage of civic offi-cials to Millcreek township to inspect the 579 acres of landwith bluffs and "a romantic little ravine through a naturalforest." Strauch described to the group how he coulddesign fine drives, lawns, and a lake on the property thathad a varied terrain much like that of Spring Grove; andthe Gazette reported that "the practiced eye of the land-scape gardener danced in ecstasy" at the possibilities of thesite. Another park was proposed in the hills of MountHarrison to the west of the city, but it was judged imprac-tical because of difficult if not impossible access up thesteep slopes. The City Council Finance Committee, how-ever, refused to allocate money for such a purchase so farfrom the city and outside of its corporate limits. 16

In 1870 Cincinnati had a few public recre-ational grounds, located in the urban basin. Predating thelarge public park movement, they were not particularlygrand showplaces for urban pride. The Eighth-Street Parkwas "simply a fenced-in graveled walk bordered by turf andprotected by shade trees" running down the center of thestreet between Vine and Elm. The so-called City Park was

only "an inclosed green plat ornamented with trees,shrubs, flower beds, and a fountain" on the east front ofthe city buildings. Water Works Park, the oldest in the city,on Third Street east of Pike, had nice views of the OhioRiver to the east of the city but was tiny and largely aban-doned. Hopkins Park, part of the old fort in the East Endeast of Sycamore Street, was simply a "small lawn onMount Auburn" donated to the city in 1866 by dry goodsmerchant and real estate developer L. C. Hopkins, whoprovided that it should "forever be kept free from build-ings, and, within two years from the conveyance, should betastefully laid out and planted with durable trees andshrubbery, and . . . inclosed with a substantial and neatiron rail fence." Lincoln and Washington Parks in the westand northern parts of the city were modest enclaves, littlemore than green public squares, not pastoral places in thesense of the mid-nineteenth-century parks movement.17

The eighteen-acre Lincoln Park was morelike the green public squares in Philadelphia or New York'sBryant Park; and the city failed to seize an opportunity toenlarge it in the late 1860s. Washington Park, dedicated in1861, was even smaller with only ten acres, bounded byRace, Elm, Twelfth, and Thirteenth streets, adjacent to thenew Exposition Building or Art Hall erected by theIndustrial Exposition Commissioners to the west and usedby various local associations and societies for festivals, theproceeds going to charity. Between 1855 and 1863, the cityobtained this land, formerly occupied by Episcopalian,United Methodist, Evangelical Lutheran, and Presbyterianburials grounds, the city's original and major graveyardsand bordered by the old pesthouse.

Although the original proposal for the cre-ation of larger public parks called for the establishment of atwelve-member board of nonpolitical, nondenominational"citizens of wealth . . . above being affected by any pecu-niary interest," nine Park Commissioners were appointedin 1870 by the mayor and confirmed by the CommonCouncil with authority to employ superintendents, engi-neers, clerks, and laborers. The commission consisted ofEnoch T. Carson, Jacob Elsas, Truman B. Handy, WilliamHenry Harrison, George Klotter, T. D. Lincoln, JosephLongworth, and ex-mayor Charles F. Wilstach, with ElliottH. Pendleton, a member of the Cincinnati HorticulturalSociety, as President. They hired Strauch as Parks'Superintendent in 1870 at a salary of $1,200 per year,although he continued in his full-time post as SpringGrove's Superintendent. Strauch favored the hiring ofJoseph Earnshaw, an English-born surveyor experienced in

Spring 1993 The Greening of Cincinnati 25

work on Spring Grove since its founding, as ParksEngineer; and of W. B. Folger, as Secretary. Strauch pro-vided general landscape plans involving the placement ofroads, ponds, structures, and plantings. He appointedforemen to carry on the "scientific" maintenance systemfirst implemented at Spring Grove. Earnshaw oversaw con-struction.18

The choice of Park Commissioners premisedsome difficulties, since some members, representing theinterests of urban wards, were generally opposed to under-taking under public auspices large, new projects removedfrom easy proximity to their constituents. ParkCommissioners also often split over allegations of excessivecost, political corruption, special interests that might profitfrom increased property values, and charges of lazy work-ers living off the public payroll but loafing on the job. Asearly as 1870, Wilstach, a "pioneer" in the effort to expandthe urban green space of Washington Park, judged it"inexpedient to undertake to provide additional parks"removed from the urban masses. William Henry Harrisonthought the city had "too much of this kind of real estateon hand — so much in fact that it was damaging the value

of down-town property." Jacob Elsas "thought the citywas well enough provided with parks already," after thefirst acquisition of land for Eden Park. CommissionPresident Elliott Pendleton remained the most vocal andactive park proponent.19

The Cincinnati Gazette criticized Mayor S.S. Davis, elected in 1871, for appointing his "politicalfriends alone" to the Park Commission, especially WilliamStoms to replace Joseph Longworth, making the ParkBoard "a mere political machine." Although "most of thepeople of the suburbs were directly interested in the city"and indeed formed an urban cultural elite intent on creat-ing new institutions, they were considered ineligible forPark Commission service because they had moved beyondmunicipal boundaries and were no longer "electors of thecity." Urban politicians felt their interests diverged fromthose who had moved to Clifton and other outlying areasand were not ready to think about urban development inlarger metropolitan terms.20

Despite these odds, Cincinnati created itsfirst naturalistic landscape in the manner of the public parkmovement at the 207 acre (216 acres by 1875) Eden Park.The city had leased with the option to buy the MountAdams property, the "Garden of Eden," from JosephLongworth and others in 1866 for $850,000 as a site forconstructing waterworks. The original proprietor,Nicholas Longworth, had tried to persuade Cincinnati toacquire the land for public purposes as early as 1818 andagain in 1846 when the city balked at the price of $1,400an acre. By the late 1850s, the property had appreciated to$10-14,000 an acre. Just as New York chose a site occupiedby a municipal reservoir for Central Park and Brooklynallocated a similar site for Prospect Park, Cincinnati finallydecided to devote for park purposes the land surroundingtwo massive new reservoirs with a capacity of 100 milliongallons of water pumped up by an engine. Unlike thecases in New York, Strauch designed the reservoirs toblend into the landscape, to resemble "natural lakes,"concealing sturdy machicolated walls and a system engi-neered to permit the draining of one while the otherremained in operation. That project alone cost $4.25 mil-lion but promised to provide a week's supply of water forthe city, enough to be tapped for emergencies like fires.21

Opened on July 1, 1870, Eden Park com-manded dramatic views over the smokey urban basin andthe Kentucky hills across the Ohio River. Located to theeast between the urban basin and the suburban EastWalnut Hills, bounded by Columbia Avenue on the east

Eighth Street Park, .844 acreof land and donated to thecity by the Piatts in 1817, wasnot formally dedicated until1868. (CHS PhotographCollection))

26 Queen City Heritage

and Gilbert Avenue on the west, it was a twenty minutecarriage drive from the post office. Strauch's landscape gar-dening plan preserved most of the trees on the site (pri-marily elm, maple, larch, beech, and evergreens) and care-fully arranged others as single specimens or in clusters toframe and accentuate views. Strauch ordered the gradingof some of the most abrupt slopes but retained many deepravines and steep hills characteristic of the local topogra-phy. He constructed "graceful," curving drives "openingup an ever-changing view of the city," the distantKentucky hills, and the suburbs of Mount Adams, MountAuburn, and Walnut Hills — "a panorama of great scopeand rare beauty." Eden Park featured a small deer parknear the entrance closest to the city. Strauch hired JamesBain as Assistant Superintendent to carry out his system of"scientific" landscape maintenance at Eden Park.Pendleton praised Strauch's work for transforming "thatwhich was unsightly into a 'thing of beauty.'"22

On the highest hill, 420 feet above the riverand set in an extensive lawn, Strauch called for a largerough-hewn stone building with expansive porches calledthe "Casino," "Shelter," or "Weather House" that cost$14,000. It provided visitors with ice water and toilets; itsexpansive porches offered an ideal vantage point for viewsover the panorama and an ornate Victorian Band Pavilionbelow in the park, surrounded by a concourse largeenough to accommodate crowds of carriages that con-vened for concerts. Other park structures were theSummer House and the preexisting Jake Newforth's wine-house, a sixty-foot-long hall with a second floor balconyand more good views. A large wooden bridge and ParkAvenue were under construction in 1875.

As at Spring Grove (and unlike the Vaux andOlmsted plan for Central Park), Strauch refused to create aseparate system of paths. He encouraged visitors to walk atwill over the grassy greensward he planted up the hillsidesand among the groves. The lack of a pedestrian path sys-tem annoyed some Cincinnatians. Women, in particular,found paths particularly desirable given the encumbrancesof voluminous skirts. Critics of Eden Park found it defi-cient and difficult of access for women and children "forwhose tender lungs the uses of breathing places have beenmost poetically sung," particularly until the MountAuburn incline opened in 1876, easing the pedestrianascent up the hillside.23

The most controversial Eden Park buildingwas the grand Romanesque archway at the entrance near-est the city designed by the local architect James W.

McLaughlin. The structure of blue ashlar limestonetrimmed with Ohio freestone was two stories high, 184 feetlong by thirty-five feet wide with an arch twenty-eight feetwide and thirty-five feet high. It had two (25'x55') roomslighted by windows, used for offices, and water closets forvisitors. It spanned the abrupt rise of hills at the entranceand doubled as a bridge with a carriage drive atop, anotherfine vantage point for distant views. But ParkCommissioners complained of defective, stained stone thathad to be whitewashed to appear fine; and the Gazettejudged it "a monument of folly in a stone structure thatcuts off not the entrance, but a most beautiful view fromthe entrance for a space of about 40 rods." Even afterStrauch squelched an even more grandiose early archwayplan that would have cost $200,000, many critics thought it"too extravagant a scale" for the site and demanded fur-ther size reduction which lowered its cost from $42,000 to$26,000. Still, initial park improvements came to $150,000,with the total for Eden Park's development nearing $1.5million by 1872. And it was far from finished.24

In response to criticisms that Eden Park wasnot easily accessible to Cincinnatians living in urban neigh-borhoods, Park Commissioners ordered work done on

Strauch improved LincolnPark by building a miniaturelake with a small waterfall, adiminutive island in the mid-dle, and a rustic grotto.(Illustrated Cincinnati, CHSPrinted Works Collection)

Spring 1993 The Greening of Cincinnati 27

older parks. Strauch installed improvements in LincolnPark, making a miniature lake with a small waterfall, adiminuative island in the middle, and a rustic grotto builtby its side in 1873 — picturesque elements common in thefar more expansive eighteenth-century English gardens.Still, Lincoln Park remained "unexceptionable in everything except its size." The overly romanticized engravedview of this part of Lincoln Park and the fanciful descrip-tion of it as "a scene like fairy land" in one guidebookmight lead foreigners to expect something on the scale ofEngland's famed Stourhead gardens. Strauch, who intro-duced swans and other "rare foreign aquatic birds" toSpring Grove, made them a feature here too; and he plant-ed Lincoln Park with new trees and beds of geraniums,fuschsia, verbenas, and other flowers in the summer, morelike Boston's Public Garden than New York's Central Park.Fine residences surrounded it, proof to the more practical-minded that urban parks functioned to raise and maintainreal estate values.25

Washington Park also received attention."Majestic Victorian pillars" were installed to mark the mainentrance on Race Street. German children from the Over-the-Rhine area used this accessible urban park adorned sim-ply by "several very fine trees, a fountain, and benches" andthe German community held its annual Schutzenfest here.Kenny praised such parks for "their beauty in the educationof the eye and taste, for relaxation from toil, and . . . forproviding an occasional supply of pure oxygen for the lungsso liable to become vitiated by the smoke-laden atmosphereof a great city." By 1876 plans were underway for construc-tion of a great municipal Music Hall next to the park onElm Street.26

Still, a cacophony of voices resounded incriticism and promotion of park-making. The Gazette lam-basted Mayor Davis for promoting "monstrous schemes"to purchase Deercreek Valley and Hamar Point forenlarged parks. Stoms called Cincinnati "the poorest forparks of any place in the United States" and quicklybecame a target of controversy for his outspoken advocacyof acquiring a piece of land dubbed the Roman Nose toround out Eden Park to Gilbert Avenue, a purchaseopposed by Longworth. Enoch Carson favored enlargingLincoln Park in his neighborhood, and Jacob Elsas agreedto vote for it if Carson would back his favorite project,adding Deer Creek to Eden Park, a project in whichPendleton might profit. These examples seemed to violatethe principal that no Board member vote on park projectsin which he held a personal interest. Conflicts of interest

and petty jealousies created a particularly difficult politicalenvironment for the making of new parks in Cincinnati,still champions of the making of pastoral public spacesremained undaunted.27

Despite intense criticism, improvements pro-gressed as Commissioners managed to start Cincinnati'ssecond pastoral park, the 170 acre Burnet Woods nearClifton to the north. It was formerly the estate of JudgeJacob Burnet, property about a mile long and over a quar-ter-mile wide, cut by many ravines and gullies. JosephLongworth said to leave it as it was, preferring to have thecity devote its resources to developing Eden Park, butthose advocating a large new park for the northern sectionof the city won out. In December 1871, the Park Boardsplit six to three in a vote to lease the property for parkpurposes for $3,000 per acre or $360,000 for the entiregrounds. Although the Commissioners proposed that thecity subdivide and sell a thin 9.5 acre strip of land on thesouth for the private building of fine houses facing thepark, thus recooping $100,000 to $150,000 for the ParkFund, the Common Council was reluctant to enter the realestate business and such residential development did notbecome part of the program.28

Burnet Woods, the only remaining piece ofwoodland in the city limits, had "a delightful grove ofbeech trees in the north half, and it is of varied surfacealternately lawn and grove for the remainder. Nature hasdone a great deal to fit it for such. A few paths and roads,or without either, it would be at once ready for the publicenjoyment." The ancient indigenous trees, "forest giants,"were considered "the only ones of any considerable bodynow left us" and hence worthy of preservation. Fewimprovements, except perhaps a simple rustic fence aroundthe grounds, were envisioned. Because of "the naturalbeauty of its scenery," judged "very remarkable," BurnetWoods seemed both a perfect "picnic" park with expansesof natural blue grass and a "woodland" park for a respite innature from city congestion. The adjacent Riddle estatehad deep ravines and sharp ridges "comparatively uselessfor private occupation" but fit for "splendid publicgrounds" and potential enlargment of the park.29

Strauch and Earnshaw collaborated on thedesign of Burnet Woods to refine grades, lay out avenues,and maximize views, work estimated at a cost of $200,000.By 1872 Strauch had started work on an avenue fromRiddle Road on Clifton Avenue, winding through the parkto Ludlow Avenue on the northeast corner, and leadingdirectly into the suburb of Clifton, creating a drive that the

28 Queen City Heritage

.CINCINNATI ra 1 8 7 2 .

3 i SQUARE MILES.

POPULATION 180 000

LUDLOW

wealthy estate owners there might either consider a dis-tinct amenity for them or a dangerous conduit easingaccess to their tranquility for the urban masses.30

Many Clifton residents, especially HenryProbasco and his friends, opposed the Burnet Woodsacquisition as threatening to disturb their quiet and "bringout people from the city" — "crowds of people onSunday" via "a street railroad" line that they anticipatedwould be built. When acquired, the site was only accessi-ble by carriage ascending Vine Street Hill or CliftonAvenue to Calhoun Street, a half-hour's drive from thecity. The press thought the park served "this class of car-riage-robe gentry" rather than the "common people,""the uncarriaged multitude" for which Burnet Woods was"almost inaccessible and nearly useless." Pedestrian accesswas very difficult. One determined visitor wrote of the dif-ficult trip to get there on foot, first taking the FreemanStreet horse-car, then climbing the Bank Street hill, arriv-

ing "pretty well fagged out."31

The demand for "grander public spaces for anew form of public promenading — by carriage" spreadthrough the 1840s and 1850s as carriage ownership became"a defining feature of urban upper-class status." Carriageownership was one mark of "Society" membership,according to Nathaniel Willis, elite New York editor of theHome Journal; and the question of providing parks forfashionable carriage promenades, in Cincinnati as in othercities, revealed questions of class conflict posed in responseto creation of supposedly "public" parks that were notreadily accessible to or designed for the mass of the pedes-trian population accustomed to the scale of the old walk-ing city.32

Strauch ordered some grading, filling ofdeeper ravines, and sodding to improve the existing"green sward" in Burnet Woods, "converted into gracefulslopes and rounded hillocks by the hand of man." He cre-

Using a map of Cincinnati in1872 which showed thecrowded conditions in thelower parts and the thinlypopulated spaces in theupper parts, a writer to theeditor argued that peopleshould have better access to

Eden Park. (Map courtesyB. Linden-Ward)

Spring 1993 The Greening of Cincinnati 29

ated a pond, fed by a creek, where small pleasure boatswere for rent; but improvements stalled in 1873 becausethe city council refused further tax-levy funds, the$100,000 Strauch needed for planned improvements.Although Strauch urged the making of a large L-shapedsection of the southern grounds into a zoological andexperimental garden with a design selected from a compe-tition of "experienced landscape artists," the city refusedto undertake such projects. The zoo was developed on asite slightly to the north under the auspices of a privatevoluntary association. Burnet Woods was open to thepublic at the end of 1873.33

Cincinnati's public parks were to remainopen at all hours; but the Park Commission passed a num-ber of regulations limiting their use. It banned animals —cattle, horses, goats, sheep, swine, geese, and unleaseddogs — in the parks, setting up a pound in Eden Park fortrespassing stray animals, where they would be held for fivedays if not claimed, then sold at public auction. Dogs wereadmitted to parks only on leash. Other regulations stipulat-ed fines for injuring plants and constructions, for fortunetelling and gambling and for bearing firearms, throwingstones, and using fireworks. Music, parades, drills, andflags were forbidden unless authorized. Nothing was to beon sale in the park without explicit permission. No hackneycoach or carriage was to be on hire in the parks and couldonly enter to drop off passengers from outside, thus leav-ing clients to find their way back on foot. Trucks, wagons,and carts bearing commercial advertisements, even if offduty, were banned, thus eliminating park access by smallbusinessmen who only had such conveyances for their fewleisure hours with their families. Carriages could drive nofaster than six miles per hour. Yet walking on the lawnswas permitted and even encouraged, unless the turf wasnewly made.34

The work of the Park Commissioners some-times elicited support, and sometimes opposition. The Starwelcomed park improvements, limited as they were: "Afew years since — about 50 too late in the world's calendar— we waked up to the necessity of preserving a few acresof ground from being covered with houses." It declaredthat "The one good credible thing we have in Cincinnatito show a stranger is Eden Park." Citing the examples ofthe 1,000 acres in New York's Central Park, the 3,000 inPhiladelphia's Fairmount, and 900 in Baltimore's DruidHill, the Star urged park expansion as well as "cheap andrapid transit" to help the people get to them.35

Park Board President Elliott Pendleton cited

the examples of the fine parks in London, Paris, Dublin,New York, Phildelphia, and Brooklyn as models forCincinnati to emulate. Pendelton declared, "Each cityfinds the park useful in bringing the people together forhealth and pleasure, forming like sentiments, and develop-ing similar tastes, thus becoming a bond of union. Shallnot the Queen City, with all its natural advantages, havesomething which shall not only be enjoyed and admired,but the praises of which shall be sounded wherever its citi-zens travel?" Pendleton assured the public that park fundshad been "economically invested" to promote "health tothe body, strength to the mind and feeling to the heart" tobenefit each citizen. He emphasized the "sanitary" as wellas psychological influences of parks as a way to counteractmore practical-minded critics. As a major park proponent,Pendleton asked, "Who can over estimate their value?" —knowing that many voices, particularly those of commer-cial interests, definitely underrated them, underminingefforts to expand those existing or to create new ones. Hecountered opponents with the economic argument thatproperty values more than doubled near parks, showing"that park property, well bought, and honestly and eco-nomically managed, is a speculation to the city. The moneyspent is not thrown away, but simply transferred from thepockets of those who can afford it, into the hands of thosewho 'earn their bread by the sweat of their brows,' whilethe city reaps her advantage by the increased value andbeauty of her property."36

Many other voices, however, questioned thevalue of "municipal ruralizing." The Commercial generallyopposed parks as sink-holes for unnecessary public expen-ditures if not outright objects of bribery and corruption, areflection of the personal views of its editor, MuratHalstead. It charged that "a grand scheme for plunderingthe city . . . has been nursed with assiduity for years," "aplot to rob the people of Cincinnati" through park pro-jects, and "a pretense of public demands which do notexist." One article in the paper declared that "it does notmake much difference to the mass of voters whether parksare worth what they cost or not." But the "mass of voters"was dominated by relatively prosperous, property-holdingmen, a fraction of the public made up of women and chil-dren, many of the poorer sort, who might actually benefitfrom the parks if considered as more than picturesque des-tinations for drives of those who owned fine carriages.37

Commercial interests, fiscal conservatives,and pragmatists opposing new parks claimed they onlywanted to achieve municipal solvency, to keep city govern-

30 Queen City Heritage

ment from expending money on new, unprecedented pub-lic projects. It was already an era of skyrocketing taxes andassessments to fund the practical public improvements —street paving, sewers, gas lights — that drastically raisedthe carrying costs of real estate impacting most of ownersof smaller properties. Park proponents tended to be largeproperty holders and those with older money — thosewhose real estate values would appreciate because of parkdevelopment and offset increased taxes. Opponents wereoften small- to medium-sized businessmen, includingmany of the more prosperous German entrepreneurs —those whose present or future enterprises might be threat-ened by turning land that might be used for industry, par-ticularly of the dirty sort, into parks and those who wouldfeel increased levies for parks the most. Many predicted anenormous tax increase would result and fall heavily onsmall businesses. The city debt threatened to reach $35million; and some even predicted municipal bankruptcy.Park Commissioner T. D. Lincoln calculated thatCincinnati had "spent ten times as much for park propertyas New York, Baltimore, and Brooklyn, more than St.Louis or almost any other city." He judged further pro-jects "extravagant." "Four-fifth of all the parks in theworld have cost the cities owning them little or nothing,"declared another commissioner. Handy noted that manygreen spaces in other cities, especially in Europe, were"very old parks . . . founded before the city fairly grew uparound them."38

Such heated debate over "Progress versusParks" raged in many American cities. In Washington,Congressmen wrangled over proposals for taking over acentral section of the Mall, designed as a picturesque parkby Downing, to make room for a railroad terminal.Factional voices were even more intense in Cincinnatigiven the limits of local topography for easy expansion ofdevelopment and the growing frustrations of the businesssector after the Civil War as the city struggled to keep upwith the more rapidly rising fortunes of other midwesterncities. As early as 1877, proposals appeared for the conver-sion of Lincoln Park into a depot site for the SouthernRailway.39 Articles in the Commercial, reflecting the opin-ions of editor Murat Halsted, painted excessively negativespictures of the parks. Critics picked apart every detail ofpark design and use. One hostile observer scoffed at the"fine display of natural rock" resembling "grinning skele-tons" unearthed in Eden Park: "In a word, the Park . . . isan abortion. Though nature has been lavish in her gifts . . . ,the ruthless hand of man, in the name of desecrated art, has

robbed it of many of its beauties, and . . . will still furtherdenude it, if the present vandalism is allowed to proceed."This untutored eye ignored the fact that Central Park wasfamed for its rock outcroppings, indeed considered desirableto augment a picturesque landscape. Lincoln Park was fullof "street dirt, kitchen bones, horse litter, and dead cats."Eden Park attracted "improper women"; and the park-mak-ing project itself was characterized as "an infirmary or refugefor broken-down bummers, political mendicants, or othersincapable of doing a fair day's labor." The Commercial con-tended that "In our opinion [parks] are not of muchaccount. They have been used to run cities in debt on falsepretenses." Halsted envisioned Cincinnati as specializing in"national conventions," becoming "the social center andmusical metropolis of America." For him, somehow, parkswere not central to that agenda.40

Defenders of Cincinnati's park design quick-ly responded in defense of Strauch's familiarity withEuropean landscapes and Central Park, emphasizing thegenius and the conventionality of his "rural" design tasteput to work on Cincinnati parks. Still, some park criticscomplained that Eden Park and Burnet Woods had no for-mal design competition, as had been the case in NewYork's Central Park, and that designs and topographicalsurveys of the land were not put on public display.Strauch, although largely responsible for park improve-ments in the 1870s, had encouraged such competitions butrealized that the city was not committed enough to parkdevelopment to formalize the process in such a way, thatmany local interests wanted to keep the work of park-mak-ing purely local and under their control.41

Other voices echoed arguments of parkadvocacy often heard in other cities. Cincinnati was tohave "parks for the people," equally accessible to the poorand the less than genteel. Joseph Longworth, expelledfrom the Park Commission after just one year's service,continued to speak out in 1872: "The only hope we haveof reclaiming the vicious part of the community is by per-mitting them to use the innocent things God gave for allmen. I should like to see our parks infested at night withthe poor foot-loose population that have got no place tosleep." Longworth went further than most of the moralistselsewhere who simply postulated that parks would elevatethe "dangerous classes," and his opinions ran counter tomany more vocal Cincinnatians who repeatedly called formore stringent restrictions of behavior and park use to beenforced by watchmen and police.42

Pendleton faced intense opposition within

Spring 1993 The Greening of Cincinnati 31

the Park Commission itself, particularly from WilliamStoms, a "poetic and gushing old gentleman" who held acommission seat from 1871. In 1872 Stoms proposed sell-ing a part of Eden Park known as the Roman Nose. In1874 he issued a resolution that no more monies notalready under contract should be expended on parks, par-ticularly on Burnet Woods and Eden Park. Stoms alsoharassed Strauch's Assistant Superintendent James Bain atEden Park both personally and in the press with allega-tions of tyrannical control over workers, prompting Bain'sresignation in 1875. Strauch likewise resigned that year,although he volunteered to continue providing his designservices and advice free of charge.43

The persistence of these disagreements andfactors beyond local control intervened to curtailCincinnati's park-making. The Panic of 1873, a secondarypostwar economic depression, a relatively minor economicglitch nationally when Congress suspended the coining ofsilver, but which nevertheless lasted into 1879, fedincreased fiscal conservatism on the local level; and it pre-cipitated an era of municipal fiscal retrenchment across thenation. Cincinnati felt particularly squeezed by economicdecline as Chicago usurped its antebellum role as entrepotfor the midwest and west. Many wealthy Cincinnatians,"pillars" of the community, experienced devastating finan-cial reversals in the last decades of the century.Commercial interests, never enthusiastic about park devel-opment, became even more reluctant to allocate publicmonies for such purposes. Although the Cincinnati ParkCommission could have provided work for many of theunemployed as some local manufacturing fell upon hardtimes, the pre-existing controversy over park-making inthe commercial sector spelled an end to the first era ofpark development.44

Through the 1870s, many Park Commissionersremained reluctant to expand the young park system. As earlyas 1872 some declared that "we have all the parks we requireand all that the city in its present condition can afford. . . . Wemust remember that we have very wide streets in Cincinnatiand seven or eight market places that will be taken away andconverted into parks some day — into such parks as the oneof Eighth Street. We have already three times as much parkproperty as New York in relation to our population and tax-able property." Even Stoms predicted that Seventh Street"will be a park by itself some of these days." Opposition toadditional park-making stemmed from sensitivity to thecost of leasing or buying more land to form new parks orto expand existing ones, especially in the business portion

THE CITY'S NEW JEWEL.

*foo Avon dale

of the city; but projects for parks more distant from thecity met with even quicker rejection. With little discussion,commissioners rejected the proposal of Robert Mitchell ofAvondale that they purchase 1700 acres of outlying territo-ry beyond Spring Grove for park purposes at a cost rang-ing from $1,000 to $3,000 per acre, questioning whether itwould only serve those with fine horses and clothes versusthe "toiling thousands" who would have to pay a week'swages to get to it.45

In 1871 the city acquiredBurnet Woods, a long paral-lelogram, slightly irregular onthe northern end, boundedon the north by LudlowAvenue, the west by CliftonAvenue, the south by

Calhoun Street, and on theeast by a row of lots frontingon McMillan Street. TheCommercial called the newpark, "The City's New Jewel"and a "West EndComplement to our East End

Eden." (Map courtesyB. Linden-Ward)

32 Queen City Heritage

Similarly, most Park Commissioners turned adeaf ear to the urging by the Cincinnati Academy ofMedicine in 1872 that the Mill Creek Valley, a "feverbreeder," be taken for park purposes for the general "sani-tary benefit," to improve the city's air purity by preventingwinds from the west from picking up noxious effluvia fromslaughter-house refuse and sewerage there. Reclamationwould involve a strip of marshy bottom lands, one-half tothree-quarters of a mile wide, with the southern end nearDayton Street. The proposed park would have McLeanAvenue along its eastern boundary, judged a fine site for ahorse railroad that would connect with other lines in theWest End and those on Third and Seventh streets, makingthe park accessible to those at opposite ends of the city.Strauch proposed making a lake and a waterfall capable ofrunning mills on the site, referring to the damming of theSchuylkill River in Philadelphia to create the waterworksand mills next to Fairmount Park.46

Opponents of Millcreek park developmentcharged that advocates of the land reclamation had person-al financial interest in the project — "a fraud," "a most fla-grant humbug," and a "puerile" proposal. TheCommercial declared that "The purveyors of pig-pens forpark purposes are rampant." Opponents predicted that theswamps and inherently impure subsoil would continue tobreed fevers even if filled, although public health advocatesnoted that infill would serve not only as a deodorizer butto eliminate the primary problem, stagnant water. TheCommercial estimated that the cost of converting the MillCreek into park land would cost $2 million and involveunnecessary straightening of the stream to establish "apuddle there for pleasure boats." It suspected "public rob-bery where there is the pretense of public improvement."Referring to the costs for Eden Park, the newspaper pre-dicted formation of a "sink hole for millions in either endof the city."47

Debate also developed around the proposedpurchase of Harmer Square, or the "Flat-Iron," for $85,000from a family based in Philadelphia and for extension ofLincoln Park and purchase of Deer Creek as an addition toEden Park. Those pushing the addition of twenty-sevenacres to Lincoln Park as a "public necessity" noted theheavy use of that "beautiful oasis in the desert of bricks"by a class of Cincinnatians who needed recreationalgrounds in easy walking distance from their homes —20,000 pedestrians crowded onto insufficient benches oneJuly evening in 1872. Folks from that urban neighborhoodcould not afford the time nor the transportation costs to

get to Eden Park or Burnet Woods; but the Commercialdiscouraged expansion, noting that Commissioner EnochCarson stood to profit personally from the venture andbartered his support for other commissioners' pet projectsin exchange for their votes for his.48

Proponents of adding forty-five acres of theDeer Creek along Gilbert Avenue to Eden Park arguedthat their project would eliminate a "nuisance" by abolish-ing slaughter houses there and rehabilitating another"unwholesome Valley." Opponents pointed out that suchbusinesses were already moving to the Millcreek Valleywest of the city. Stoms led a petition campaign for the pro-ject that collected 5,000 signatures. Strauch proposed creat-ing a succession of lakes and ponds in the area, includingone at the entrance to Eden Park49

Opponents of the Deer Creek additionnoted that "the gulch" would need so much infill that itwould cost over a million dollars, bringing the cost of theexpanded Eden Park alone to $3.5 million. The project,some charged, would benefit those who wanted to extenda railroad line through that parcel of land and would takethe right-of-way once the city improved it. The "gentry"disliked the addition that would put Eden Park in more"convenient reach of the people who go there on foot." Inlate 1872 the Board voted five to four against the project.50

Reacting particularly to the Mill Creek and

The development of theincline planes in Cincinnatibrought easy access to thehilltops and Eden Park andBurnet Woods forCincinnatians who lived inthe crowded basin of the

city. (CHS PhotographCollection)

Spring 1993 The Greening of Cincinnati 33

Deer Creek proposals, the Commercial noted that removalof businesses from those areas for "absolutely unproduc-tive" parks "would ruin the city." The Deer Creek was "agreat and dirty job . . . linked with a chain of jobs extend-ing all around the city. To follow the example of theTammany thieves and put out 'improvement bonds'"would surely add "ten millions . . . to our city debt." TheCommercial preferred still-houses and slaughterhouses as"institutions that are of some value to Cincinnati," unlikeparks made by "the confiscation of the city" of potentiallyproductive property only "for the benefit of the twin sci-ences of civil engineering and landscape gardening." TheCommercial again accused Park Board members of "rascal-ity," "chicanery," and having monetary interests served bytheir "schemes to rob the City Treasury."51

By 1872 even the Gazette, which supportedof the Deer Creek addition to Eden Park, was willing to airother arguments by printing an opponent's letter whichconcluded that "There is a wild and ignorant notion thatparks pay a money profit, which men use as a cover for themost absurdly extravagant schemes . . . . Parks are a deadinvestment of all their cost, in pleasure . . . . The richestcitizen in Cincinnati would scoff at the idea of paying$50,000 an acre for buying and filling land in Millcreek andDeercreek valleys for his pleasure grounds." The Gazettecountered that the project would increase adjacent proper-ty taxes and lessen those in older parts of the city. Thepaper favored the Deer Creek addition as a way to openEden Park to those who could only reach it on foot, espe-cially the poor on the west side of the creek in Germanneighborhoods.52

Opponents of park-making and expansionraised issues of geographic equity, knowing that a new parkon one end of the city would incite demands by those inother sections. Extension of Eden Park would, opponentsargued, "create a demand in the West End for a park ofsimilar dimensions and that would involve the city inanother large and unnecessary expenditure." EnochCarson added, "the people suffered more from crowdedhouses than from want of parks." A substantial faction offragile Park Commissioners declared, "Each of these Parkjobs contains the germ of another. . . . Why not, in thename of common sense and reasonable economy, kill offthe whole brood of jobs of this kind and have done withthem?" Despite a citizen initiative through the CommonCouncil in favor of the Deer Creek project, the Park Boardrecommended against it.53

Diverse and conflicting interests shaped

much of the criticism of new parks. Opponents pointedout that most members of the working masses, the "coach-less thousands," could not escape the confines of the"walking city" in the basin in their rare leisure hours onSundays. Eden Park was "too far off for the poor" of thecity. Newspaper accounts depicting music concerts in EdenPark as elite social events may have discouraged some ofthe working class that might have been ambitious enoughto scale the heights to Eden Park on foot. One describedthe fine society convening for "the grand review" at con-certs in landaus, phaetons, barouches, tandems, chariots,buggies, and Irish jaunting-cars, with Pendleton arrivingwith his brother-in-law, the Reverend Schenck ofBrooklyn, "in his elegant four-in-hand with footmenbehind." The upper class used the park "to escape the din,the sooty smoke, and heat of a busy city." So great was thecrush of carriages of the elite around the bandstand thatthe surrounding concourse had to be expanded in 1872.54

Only Lincoln Park was judged "a favoriteplay ground for the children of the neighborhood." Abouta dozen rental boats plied the waters of its small lake, andthe park became "the resort of thousands" on summerevenings. Evening concerts there and in Washington Parkattracted crowds of ordinary Cincinnatians, most on foot.In winter throngs of iceskaters packed the frozen waters,enjoying a genteel sport of recent vogue. Like other parksdesigned by Strauch's generation, however, even thosewith more extensive terrain provided only for passive recre-ation, not for active play like baseball (although it was per-mitted on the lawns), despite the growing popularity andeven professionalization of that game in the city.55

Contentiousness over design, expansion, anduses of pastoral landscapes never arose in the cases of"rural" or garden cemeteries like Spring Grove, whichwere in fact only quasi-public, most founded and fundedby non-profit corporations and voluntary associations ofthe urban cultural elite. Although precedents and proto-types of the landscapes of many mid-nineteenth-centurypublic parks, garden cemeteries were formed under entirelydifferent auspices that did not require public monies ordebate over just how public "public" space should be.Through the squabbling over the parks, Adolph Strauchstaunchly maintained an impeccable reputation, not onlyfor the high quality of his local and increasingly nationallandscape design projects but for his insistance on remain-ing above the political fray, for doing his public service atthe end even without pay. Even the most rabid, partisan,journalistic critics of public parks had kind words for

34 Queen City Heritage

Strauch's accomplishments. In 1871 the Commercialpraised "his rugged sledge-hammer and incorruptible hon-esty" and in 1873 called him "honest and capable andunimcumbered by political allegiance to any ring or partyand therefore [able to] stand between political jack alls andtheir coveted and accustomed plunder." Journalists rav-aged the work of the architect, the engineer, and the EdenPark foreman; but they could not fault the simple taste andpublic spiritedness of Strauch.56

Pro-park voices were drowned out by antag-onists who managed to reduce park funding. Pendletonwas not as successful in his arguments as his more pinch-penny commercial opponents in discouraging furtherwork. The tax levy was reduced from $60,131 in 1871 to$43,750 in 1872, a sum inadequate for regular maintenance,estimated at $125,000 annually, let alone for completingplanned improvements. By the end of 1873, Pendletonjudged "the smallness of the levy for the use of the Boardin the past year amounted to almost a prohibition of anynew improvment in any of the parks," a phenomenon "tothe very great embarrassment of the park service." In 1874the Park Fund amounted to only $36,392 or .20 mills outof a total of 16.00 mills for public projects and services.Pendleton continued his crusade: "A driving park withoutdrives, walks, trees lakes, grottos, etc. fails to meet theobject for which it was commenced and the reasonableexpections of the public." He continued to protest that"Pleasure grounds must be established for the young,where suitable and proper means of recreation may beafforded, thus giving to the youth of the city an induce-ment to indulge in harmless amusements and to take exer-cise in the open air, thereby adding strength to their moraland physical character."57

Still, booster publications praising the devel-oping park system in the 1870s reveal none of the acrimonythat raged over park design and expansion and generallyexaggerated in boasting of the city's eight parks. D. J.Kenny's Illustrated Cincinnati (1875) recommended the"Grand Drive" through Avondale, the Zoological Garden,Burnet Woods, Clifton, and Spring Grove, returning tothe city via the boulevard through the Mill Creek Valley.He deemed Clifton "one of the garden-spots of America,"with "hill, dale, lawn, ravine, field, and forest, interspersedwith bright evergreens and shrubbery, blossom with shadynooks and sunny glades, in which nestle the roomy, coolverandas and graveled walks of the fine homes of Clifton."But Clifton was a private, elite suburban landscape; andonly the wealthiest could afford horse-drawn vehicles, let

alone spare the five hours estimated for the "GrandDrive."58

Burnet Woods and Eden Parks remainedCincinnati's major contributions of the era of the largepublic park mania. Kenny waxed particularly poetic inpraise of the city's Eden: "With all the emerald verdure ofthe turf at his feet, with the green foliage of the trees allaround him, and the sheen of the water, lit up by the set-ting sun, the traveler, as he wanders through these lovelywalks, . . . And then, as again and again, clearly and dis-tinctly, the sweet church bells ring out above the busy city,with its restless, swarming thousands, how easily might hefancy himself in some great temple of nature." Kennyrevealed one of the last gasps of romantic idealism that hadinformed the building of the first picturesque parks acrossthe nation, an ideology and a cultural perspective that wasbecoming rapidly anachronistic in the last quarter of thenineteenth century and that had never commanded a largeconstituency in Cincinnati, especially among those withauthority for park building.59

Kenny's rhetoric contrasted markedly withrancorous contemporaneous assessments of the parks in thelocal press based on economic pragmatism. Like mostbooster literature in other cities about the fine, new greenspaces as urban amenities, Kenny painted too much of a fic-tionalized, rosy picture, implying consensus that simply didnot exist in the arduous, contentious task of public park-making. Until recently, the story of the intense factionaldebates that raged in the making of America's first andunprecedented urban "pleasure grounds" touted as for thepeople simply has been ignored. The extensive contempora-neous booster and historical literature on park design hasfocused on landscape aesthetics and the heroic visiondesigners in the process of professionalization. It has skirtedlocal stories of contentiousness, squabbles played out inpublic meetings and the local press, and questions abouthow truly "public" these picturesque enclaves would be. Ithas ignored particularly local problems of demographicsand economics, especially in an age when the status and for-tunes of individual cities were so dependent on their rise orfall in the great "urban sweepstakes," the index of vicissi-tudes in local prosperity. In Cincinnati, the relatively declin-ing fortunes of the city compared to other boomingmetropolises underlay some of the reluctance to buildextensive new parks in the 1870s.60

Also, the original mechanism for park cre-ation was experimental and flawed in procedural terms,representative of the political chaos that characterized

Spring 1993 The Greening of Cincinnati 35

municipal governments struggling to provide unprecedent-ed municipal services. The Board of Park Commissionerswas divided internally from its inception. The city councilcould not act on park matters until the Park Board recom-mended specific projects for a vote; and after the fall of1872, the council voted no more appropriations for parks,leaving the commissioners bankrupt and forced to dis-charge many workers. The council and the Board ofImprovements also repeatedly infringed on ParkCommissioners' authority by selling, renting, or grantingprivileges for park use, decisions often ruled by arbitraryfavoritism. The much publicized contentiousness withinthe Park Commission prompted calls for the abolition ofthe board as early as 1872. The board itself seemed to beput on trial in 1874 in public hearings in the city councilinvestigating alleged corruption in the acquisition ofBurnet Woods. Although none was found, the procedingssounded a death knell for the board which issued its lastreport on January 1,1875.61

An act of the Ohio legislature abolished thePark Commissioners formally on March 17, 1876, placingCincinnati parks under the authority of a Board of PublicWorks, five commissioners, freeholders of the city to beelected to serve five-year terms each, with one seat chang-ing every year. The legislature mandated a Board of PublicWorks for all cities with populations over 150,000, not justfor Cincinnati, to replace Trustees of Waterworks, theBoard of Improvement, Commissioners of Sewers, thePlatting Commission, and the Park Commissioners. Eachnew commissioner received an annual salary of $3,500, hadto "devote their entire time and attention to the duties oftheir office," had to post a $50,000 personal bond, andcould be removed for malfeasance, inefficiency, or incom-petency. All contracts for work or materials for parks hadto be advertised publicly for ten days and then awarded bythe city to the lowest bidder. The reform reflected a gener-al attempt evident across the nation to formalize and makemore efficient centralization the development and deliveryof new public services.62

Creation of the Board of Public Works metwith mixed reviews, depending on existing attitudes aboutpark development. The Gazette had long criticized "theway the control of our municipal legislation by a sectionalminority, through an unequal system of wards, has givenschemes for private gain the advantage over considerationsof public welfare," a system that often squelched the park-making it advocated. The Enquirer criticized the newarrangement as a product of the Hayes legislature "in

humble imitation of the law under which Tweed broughtNew York to the verge of bankruptcy." It demanded thatthe new board restore Strauch to the superintendency ofparks because of "his qualifications, integrity, and theunfortunate causes attending his resignation," with harshwords for his successor Earnshaw.63

The Board of Public Works, its jurisdictionscattered over so many public services, did little to improveexisting parks let alone to create new ones. As early as1880, Henry Probasco observed that Burnet Woods was"already beginning to show evidence of neglect." Existingplantings suffered from "depredations," and few new treesor shrubs had been added. Probasco called for a privateendowment to remedy the public deficiencies, knowingthat additional city monies would not be forthcoming; butthose local philanthropists still able to contribute to thepublic good turned their attention to other new culturalinstitutions.64

Through the 1880s and 1890s, the furor hor-tensis, the mania for making pastoral landscapes, abated. In1882, twenty acres of Eden Park were taken for the ArtMuseum Association which opened its neoclassical build-ing in 1886. In 1888 Horticultural Hall was built inWashington Park for Cincinnati's Centennial Exposition,occupying a major part of that small green open space. In1889 and 1895, the University of Cincinnati moved to sitesin Burnet Woods, eventually taking about a half of theoriginal park. One rare new embellishment to the parksappeared in 1894 when the 172 foot Norman Gothic WaterTower was added to Eden Park, remaining a popular van-tage point until closed to public access in 1912.Nonetheless, by the turn of the century one booster esti-mated that Cincinnati averaged an acre of parks for every770 people, almost twice the public green space of someother large American cities. By 1900 there was "little callfor [additional] improvement upon the pristine attractionsof Burnet Woods or Eden Park, the largest of the publicpleasances of the city."65

Still, Cincinnati, unlike in many other met-ropolitan areas, did not have a park system, the extensivenetwork of parks and tree-lined parkways or boulevardsthat made green public open spaces part of the expandingurban complex, preserved from haphazard developmentand providing access to these amenities to larger portionsof the city's growing population. Indeed, arguments usedagainst new parks indicated a reluctance to undertake pro-jects that were being demanded on a dispersed metropoli-tan scale. In contrast, Chicago had planned a park system

36 Queen City Heritage

totalling 1,900 acres, including six parks averaging 250 acreseach, many linked to the urban core by parkways from 200to 250 feet wide. In 1871 Buffalo started a comprehensivedevelopment plan including a 300 acre suburban parkapproached by a parkway from the center city — a total of530 acres. The influential landscape architect H. W. S.Cleveland advocated a park system for Minneapolis-St.Paul in 1872. By the mid-1870s, St. Louis boasted 2,100acres of land set aside for development for public recre-ation, including of parcel of 1,350 acres; and it had alreadycompleted the 277 acre Tower Grove Park and begun con-struction of a twelve-mile-long parkway. San Franciscoreserved 1,100 acres of grounds, with over 1,000 acres in

Golden Gate Park overlooking the Pacific Ocean from athree-mile-long shore drive.66

Not until 1906 did the Cincinnati CityCouncil issue a $15,000 bond to commission a comprehen-sive study for an urban park system from noted Kansas Citylandscape architect George E. Kessler, inaugurating a newera in Cincinnati's park making. Kessler made recommen-dations that Strauch and the first generation of Cincinnatipark proponents had long advocated — further develop-ment of the dramatic natural hillside and hilltop topogra-phy surrounding the city in a systematic way, providingparks in various sectors of the metropolitan area linked bytreelined boulevards. Unfortunately, Strauch and his col-

fli

Many Clifton residentsopposed the acquisition ofBurnet Woods fearing"crowds of people" woulddisturb their quiet. (CHSPhotograph Collection)

Spring 1993 The Greening of Cincinnati 37

leagues were unable to achieve as much as they wishedbecause of political and economic problems particular tothe character and declining fortunes of the city in the1870s. But through development of various notable privateand public landscapes, they laid the foundation for thegreening of Cincinnati.

1. Roger B. Martin, "Metropolitan Open Spaces," in William H.Tischler, ed. American Landscape Architecture: Designers and Places(Washington, D.C., 1989), 165.2. Sidney Maxwell, The Suburbs of Cincinnati (New York, 1870),quoted in John Clubbe, Cincinnati Observed:Architecture andHistory (Columbus, Ohio, 1992), 304. Vaux and Olmsted did not pro-duce the much touted design for Riverside, Illinois until 1868-70.3. Clubbe, 311-13. Robert Buchanan founded the CincinnatiHorticultural Society in 1843 and under those auspices, led in found-ing Spring Grove Cemetery in 1845. Peter and William Neff headed acommittee of horticulturists that chose the original 166 acre site, theold Garrard farm about four miles north of the city. It cost $88 peracre, bringing the initial investment to $15,000. Spring Grove wasexpanded by 40 acres in 1847. Bowler's estate became Mt. Storm Parkin 1911 when acquired by the City of Cincinnati.4. John Claudius Loudon, On the Laying Out, Planting andManaging of Cemeteries; and on the Improvement of Churchyards(London, 1843), quoted in Adolph Strauch, Spring Grove Cemetery:Its History and Improvements (Cincinnati, 1869) , 9-10, 28. For a his-tory of the aesthetic origins of the American "rural" cemetery move-ment in the jardin anglais, see Blanche Linden-Ward, Silent City ona Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston's Mount Auburn Cemetery(Columbus, Ohio, 1989).5. Strauch, Spring Grove, 4-5. For an analysis of Strauch's work, seeLinden-Ward and Alan Ward, "Spring Grove: The Role of the RuralCemetery in American Landscape Design." Landscape Architecture75:5 (Sept/Oct. 1985), 126-31, 140. The "picturesque"had irregularlines, abrupt and broken surfaces, and more natural, wild plantgrowth, with ruins or rustic buildings as "embellishments." The"beautiful" was characterized by wider, more easily flowing curvesand soft surfaces in the form of expansive lawns framed by luxuriantbut more carefully tended vegetation, with decorative structuresoften of neoclassical architecture.6. Strauch's extensive correspondence included letters of recognitionfrom the U.S. Department of Agriculture (1862); the Commissionersof New York's Central Park (1865); the Zoological Society of London(1865); the Board of Managers of Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield,Illinois (1877) where President Abraham Lincoln was buried; theSociete Royale d'Agriculture et de Botanique in Paris (1878), invitinghim to be a judge on the 10th Exposition Internationaled'Horticulture; Chicago's Forest Home Cemetery (1880); the LandDepartment of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad (1881); the land-scape architect J.P.F. Kuhlman of San Francisco (1882); and AbneyPark Cemetery, London (1883). Strauch, Spring Grove 6, 7-8;Frederick Law Olmsted to Strauch, March 12,1875, OlmstedAssociates papers, Library of Congress, microfilm edition, reel 14.7. Philadelphia horticulturist quoted in Clubbe, 304; J.D. Kenny,Illustrated Cincinnati: A Pictorial Handbook of the Queen City(Cincinnati, 1875), 319. In 1874 Spring Grove had an estimated150,000 recreational visitors, not counting those attending funerals.8. Catherine H. Howett, "Andrew Jackson Downing, " in Tischler,ed., 30, 33.9. Andrew Jackson Downing, "Improving the Park Ground of theCity of Washington," letter to President Millard Fillmore, Winterthur