The Fish that Time Forgot

-

Upload

michael-kallok -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

5

description

Transcript of The Fish that Time Forgot

26 Minnesota Conservation VolunteerBy Michael A. Kallok Photography by Mike Dvorak

-

-

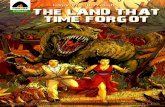

The FishThat

Time

Forgot

-Catching this muskie doesn’t take the legendary 10,000 casts, but it does take 10,000 steps to get there and back.

28 Minnesota Conservation Volunteer November–December 2008 29

These words lodged fast in my memory amid small talk bouncing between fishing guides at a restaurant near International Falls. Like precious ore, they tumbled in my imagination for years until the idea of going there became too shiny to resist.

Shoepack Lake and its muskel-lunge (Esox masquinongy) have long lured, thrilled, fascinated, and—somewhat famously—disappointed anglers with their diminutive size. This reputation did nothing to tar-nish the glimmering promise of a remote body of water teeming with the fish of 10,000 casts.

Without a floatplane, getting to Shoepack has never been easy. A strong northwest wind could swamp my plan to paddle across Lake Kabetogama. Like the 17-foot beat-up aluminum canoe jutting over the windshield, that pos-sibility hung overhead for 250 miles as my fishing partner Mike Dvorak and I headed north from the Twin Cities to Kabetogama. This border-water town of 156 residents offers a last chance for supplies before St. Louis County Road 122 ends at the watery doorstep of Voyageurs National Park.

It seems fitting that you need a boat to access Minnesota’s only national park. Voyageurs’ most prominent land-mass is the Kabetogama Peninsula, 75,000 acres of roadless wilderness

surrounded by the vast interconnect-ed waters of Rainy, Namakan, and Kabetogama lakes. Shoepack Lake, one of 26 inland lakes on the penin-sula, sits roughly in the middle of it.

In 2006 the discovery of spiny water fleas in Rainy Lake led to a ban on floatplane traffic to all of the peninsu-la’s inland lakes. Because this invasive critter can hitch a ride on boats from infested waters, the park also prohibits privately owned watercraft on the pen-insula lakes. Instead the National Park Service rents canoes and rowboats on many of them.

The keys to the canoe we’d reserved on Little Shoepack Lake wouldn’t be

Previous pages: Few anglers make the hike to Shoepack Lake, but those who do are rewarded with willing muskie and solitude.

Center: Shoepack Lake’s water vividly reflects the changing sky and the pen-insula’s stately white pines. Top right: Pale corydalis grows from outcrops of granite and schist after fire swept through here in 2004.

available until noon, so we ducked in to the nearby Bait N’ Bite Café.

Young Man’s Trip. We find a table near the wall that separates the bacon

and eggs half of the business from the hiss of aerators pushing oxygen into minnow tanks. Allen Burchell, 67, and Ed Town, 82, join us. They are old- timers who made their living on and around Lake Kabetogama in one way or another as commercial fishermen, guides, and resort owners. Fishing sto-ries flow as liberally as the coffee here, and I’m looking forward to hearing a few from Shoepack Lake.

“I wish I was going with you guys,

-

-

•

Kabetogama PeninsulaShoepack Lake 48° 30’N, 92° 53’W

“Getting there isn’t easy, but Shoepack Lake is full of muskie.”

30 Minnesota Conservation Volunteer November–December 2008 31

Top: A network of trails to lakes on the eastern end of the peninsula begins at the northern shore of Eks Bay on Lake Kabetogama. The trail to Little Shoepack Lake leads over a series of steep gradients.

Bottom: Fishing guides Ed Town (left) and Allen Burchell reconnect with memories of Shoepack Lake and its muskie at the Bait N’ Bite Café in Kabetogama.

but Shoepack Lake is a young man’s trip,” Burchell says. “It always has been.” Tucking his thumbs under his suspenders, he leans back in his chair to gauge our reaction.

Town confirms the statement with a nod and adds, “The black flies and mos-quitoes can just about eat you up.”

He first visited Shoepack Lake nearly 70 years ago. Like Burchell, he returned there occasionally with people who, like me, had heard stories about a little lake full of muskies in the middle of Kabetogama Peninsula.

“I’ve never caught a big muskie in Shoepack Lake,” says Town. “A lot of peo-ple tell you they catch big ones, but I’m telling you the truth.”

Shoepack Lake muskies rarely, if ever, attain 40 inches in length—a trait, I would learn, inextricably tied to the lake’s isolation.

Setting Out. We launch our nine-mile journey to Shoepack by loading our canoe into the water at the Ash River Visitor Center. The calm of this mid-June morning appears to have settled in for the day, but urgency crackles across the parking lot like lightning ahead of a cold front. Vacationers, eager to break free from the blacktop, hustle fishing rods, coolers, and camping gear into seaworthy-looking runabouts and back them down the concrete boat ramp. As we slip out past the end of the dock, our loaded canoe feels insignificant on the 26,000-acre expanse of Lake Kabetogama.

A gentle breeze tousles sequined waves across the lake surface and whisks away my

pretrip visions of froth-spitting whitecaps curling over the bow. A large wake from a supply barge is the only hazard we face dur-ing our two-hour paddle to the peninsula.

A set of stairs on the north bank of Eks Bay clearly defines the trailhead. Perched safely on dry land, white-throated sparrows are singing the praises of their northern home—sooo seeeeeee dididi dididi dididi. Not far from this peninsula, citizens across the border might argue the tune is “Oh Sweet Canada, Canada, Canada.”

We secure the canoe to a big red pine and set out on the first leg of our two-mile hike. It leads over a series of steep gradients that divide the peninsula. From Jorgens Lake, we walk northwest. The trail becomes narrow and noticeably less traveled as we move down toward low marshes and tiny tributaries that feed Little Shoepack Lake. We crest three bea-ver dams along the portage. After the establishment of Voyageurs National Park in 1975, these engineers regained diligent control over the water levels of the penin-sula’s inland lakes.

Stepping out from the dark canopy of the forest onto a sun-drenched ledge of rock, we find the sturdy aluminum canoe we had reserved to cross Little Shoepack Lake.

Shielded From Pike. The granite and schist of the Kabetogama Peninsula was formed more than 2.6 billion years ago. Red and white pines grow to dizzying heights in the thin soil on top of this rocky land, cut and polished by countless

-

-

32 Minnesota Conservation Volunteer November–December 2008 33

rains and at least four glaciations. These same forces also shaped the peninsula’s 26 inland lakes. Of these, muskie swim in only two.

We unlock the canoe and launch it onto the first muskie lake, Little Shoepack Lake—a narrow half-

mile corridor of water. At its north-ern end, we portage along a tight, unnavigable creek that connects to our destination, Shoepack Lake.

The remoteness of Shoepack shel-tered its muskie from human exploita-tion. And 10,000 years ago, the penin-sula’s geography kept them safe from a different threat: northern pike (Esox lucius). Abundant in Rainy Lake and nearly every other lake on the pen-insula, northern pike hatch earlier

than muskie. Had they reached the relatively small 300-acre confines of Shoepack Lake, they likely would have long ago consumed and outcompeted its muskies.

The lake’s single outlet stream flows several circuitous miles north

before it spills out into Rainy Lake as a film of water over a steep 160-foot granite outcrop known as “bear slide.” When the waters that covered the peninsula receded during the end of the last ice age, the precipitous rock slide provided an effective bar-rier to pike, and it continues to do so today. For 10,000 years, this place has been hard to get to.

At the end of a 200-yard portage, I feel exhilarated to be standing on

the bank of Shoepack Lake, which has existed for too long in my imagi-nation. Regulations here require anglers to release all muskie less than 40 inches. This has, in effect, turned Shoepack Lake into a catch-and-release fishery. Few muskie anglers are willing to make the trek for fish that could hardly be consid-ered trophies. Only 35 people visited Shoepack Lake in 2007.

The lake takes its name from a type of boot used by loggers. Looking at Shoepack Lake’s outline on the map, I can see it does resem-ble a boot. We had arrived at its south-pointing toe—a shallow bay ringed with reeds. We set out in the canoe toward the ankle in search of the rowboat also maintained by the park service. Our presence startles a common merganser, and it utters a series of low, incredulous croaks—whuuut? whuuut? whuuut?

We find the rowboat on a fin-ger of land near the lake’s largest island. Across the lake, a promon-tory of rock appears as an obvious campsite, and we hastily pitch our tents there. We had spent six hours reaching the lake, and it is now after 7 p.m. Enough light will hang on the horizon for several hours of fishing. We’re anxious to test the water.

First Glimpse. The muskies that live here occupy a unique footnote in the history of Minnesota fisheries man-

-

Left: From Jorgens Lake, the trail leads across three beaver dams to Little Shoepack Lake. The construction or failure of beaver dams can have a significant effect on water levels. A dam failure at Shoepack Lake’s outlet in 2001 reduced the lake’s surface area from more than 500 acres to about 300 acres.

Top: A portage trail near the outlet of Little Shoepack Lake winds along and over the small creek that emp-ties into Shoepack Lake. Bottom: As viewed from the campsite, the sun sets over Shoepack Lake.

-

34 Minnesota Conservation Volunteer November–December 2008 35

agement. In the early 1950s, the DNR set out to stock more of Minnesota’s lakes with muskie. Shoepack Lake was singled out as a brood stock source. Its ravenous muskie had an established reputation for recklessly ambushing anglers’ offerings.

From 1953 to 1960 and again from 1964 to 1972, DNR fisheries crews took musk-ies from Shoepack Lake. In the beginning they caught muskies by hook and line and airlifted them in milk cans to a hatchery in Park Rapids. In later years the crews used trap nets and delivered fertilized eggs to the hatchery. But after two decades of using progeny from Shoepack Lake, the DNR heard muskie anglers complain-ing that muskie in lakes stocked from Shoepack were too small. In the 1980s the DNR abandoned use of Shoepack strain muskie for Leech Lake strain, which regu-larly attain 50 inches or more in length.

A lake full of muskie notoriously willing to bite is a compelling reason to attempt to catch one on a fly rod, and it is a goal Dvorak and I are enthusiastic about achieving. Rowing out from the campsite, we prepare our first offerings for Shoepack’s muskies—large streamer flies designed to imitate the sucker and perch that are their prime forage. We cast these bulky flies without grace; but retrieving line foot by foot delivers an undulating motion to the long feathers, synthetic fibers, and tinsel that have been lashed to hooks with stout thread and epoxy. Confident that these flies will quickly induce a strike, I’m baffled when success is not immediate. From my fly box I produce

a black popper with a foam head as big as the cap on a one-gallon milk jug.

A series of violent false casts are required to conduct this less-than-aero-dynamic creation through the air before it plops down beside a snarl of timber near shore. A sharp pull on the fly line forces the popper’s buoyant head under-water with a loud “Bloop!”

I grin at this devious noise and relish the drip of adrenaline it delivers each time it’s reproduced.

Bloop! … Bloop! … Bloop!Five feet away, a surge of water lashes

like a tongue of lightning and crashes savagely into the side of the popper. Line sprints along the bank. The fish is invis-ible just a foot below the tannin-steeped water. Feeling resistance, it cartwheels out of the water, giving us our first glimpse of a Shoepack Lake muskie. Alongside the boat its glowering yellow eyes are a vibrant contrast to the dark emerald-iridescence of its body. The fish is small by the standards of any self-respecting muskie angler. But it’s hard not to admire this predator’s ferocious strike.

It is the first of four muskies we will hook on fly rods and release that evening. We hoot and high-five each time a fish is landed. During the day they’re difficult to catch, even with conventional tackle, but during the three hours leading up to twilight, Shoepack’s muskie oblige.

Admirers of Fish. Our campsite sits atop a bare rock outcrop with bands of pink-hued granite. Pale corydalis and

A park service rowboat provides a stable platform to cast from and catch Shoepack Lake’s infamous muskie.

-

36 Minnesota Conservation Volunteer November–December 2008 37

Bicknell’s geraniums raise their lanky stems and offer their pastel flowers to the sun. The fire that swept through here in 2004 didn’t diminish the beauty of this place. Clusters of towering white pines also managed to avoid the ravages of fire and, before the establishment of the park, logging. They are testament to this place of survivors.

Across this dark water, the ever-changing sky is reflected vividly. Peering beneath its surface—even with polarized sunglasses—is difficult, leaving room to imagine a big muskie at the end of the next cast. Some people say they catch big ones here. We do not. But on the second evening we find evidence that others have admired these fish. Behind the dorsal fin of a feisty 27-inch muskie, a thread of plastic holds a cylindrical tag the size of a matchstick. Carefully rubbing the grime from the tag, I see a three-digit number printed on bright yellow plastic. The next muskie, a dark, battle-scarred 30-inch fish, also carries a tag. Later that night, we sit by the campfire and ponder who tagged these fish—and why.

True Measure. After returning home from Shoepack Lake, I called the Department of Natural Resources Fisheries office in International Falls and learned the musk-ies were tagged by Nick Frohnauer in 2001. During his three-year graduate study of Shoepack’s muskie, Frohnauer and his crew tagged 672 muskie. Our fish, tag numbers 259 and 426, had grown only 3 inches in seven years, further

proof that Shoepack’s muskie, isolated for 10,000 years at the northern edge of their range, had evolved to grow slowly and live long.

In two days on Shoepack Lake we caught 10 muskies. Not one was longer than 30 inches, but it seems foolish to suggest a

ruler can measure these shadows that have prowled beneath this water since the end of the last ice age—as oblivious to having been admired as they are to having been forsaken. Ancient forces tucked the water these fish inhabit away like treasure. In the end, I found to briefly hold its stunning emeralds had been a privilege. nV

They may be small, but these muskie still exhibit all the ferocity of their larger kin. This one ambushed a large black popper called the “muskie boiler.”

-

* www.mndnr.gov/magazine See an animated

slide show of the journey to Shoepack Lake.

According to study data, this female muskie, number 259, was tagged by a fisheries researcher May 8, 2001. The fish was 27 inches long. When caught and released June 20, 2008, it was 30 inches long.