The First Maus (1972). Spiegelman can imagine his father’s experience in Auschwitz only by...

-

Upload

hilary-shaw -

Category

Documents

-

view

221 -

download

0

Transcript of The First Maus (1972). Spiegelman can imagine his father’s experience in Auschwitz only by...

The Generation of Postmemory

Marianne HirschBy Christenson Hannah, Diamantopoulou Angie, Nicolescu Andrei, Whiting Johnny

Overview• Hirsch looks upon the aspects of postmemory. In particular

Hirsch examines using oral recollections and photography as an intergrading part of postmemory recollections.

• Postmemory: the term describes the relationship of the second generation to events, which are often traumatic, that happened before their birth, but are so powerful and have been transmitted to them so deeply, that they seem to become their memories.

• The Postgeneration, or “hinge generation”, maintains the “sense of living connection”. At the same time, that sense is being eroded.

Overview• The “guardianship” of a traumatic event, such as the

Holocaust –Hirsch’s focus in this text –is at stake. Could this “guardianship” be connected to the “legacy” that the archives are supposed to save?

• The way in which a trauma can remind one of another trauma transcends the bounds of traditional archives.

• There is a need for aesthetic and institutional structures, which the historical archive lacks; archives of oral history, photographs, testimonies, performances, films, novels, etc.

Memory and Postmemory• There is a distinction between memory and postmemory.

Postmemory is not, in fact, real memory, but rather the transmission of the actual memory, which occurs when a trauma is so strong that the descendants of those who experience it connect deeply to the memory.

• The postgeneration “remembers” through stories, images and behaviors that they experienced as they grew up.

• The trauma has effects on the postgeneration, and that is the reason why it is affected by postmemory. The trauma becomes inter- and trans-generational.

Holocaust and Postmemory• Photography, whether it is done by

perpetrators, bystanders or the victims themselves, offers access to the event and can assume iconic and symbolic power.• The generation of postmemory

relies primarily on photography as the medium of trans-generational transmission of trauma.• Family is used as a space of

transmission, and having these familial relations allows the postgeneration to receive knowledge of past events, which then can be transmuted into history.

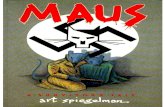

The First Maus (1972). Spiegelman can imagine his father’s experience in Auschwitz only by relating it to this public image, which was added to the family album and made personal by the arrow pointing to “Poppa”.

Photography As A Form of Memory• Photography, as a medium of postmemory, clarifies the connection

between familial and affiliate postmemory and the mechanisms by which public archives and institutions have been able both to re-embody and to re-individualize “cultural/archival” memory.

• Photographs enable us in the present not only to see and to touch that past, but also to try to reanimate it by undoing the finality of the photographic “take.”

• C. S. Peirce defines photographic images as more than purely indexical or contiguous to the object in front of the lens; they are also iconic, exhibiting a mimetic similarity to that object. Holocaust photographs are the fragmentary remnants that shape the cultural work of postmemory.

Thousands of wedding rings confiscated from Jews at Buchenwald concentration camp by the

Germans to salvage the gold, May 1945.

Woman with children in German death camp Auschwitz in Poland during Second World War. Documentary photos of the crimes of Eichmann, murderer of the Jews. Facist criminals like Eichman did not even halt for the elderly and the children. Here, children and an old woman on the way to the death barracks of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Communicative And Cultural MemoryHirsch also reflects upon Jan Assmann’s work Das Kulturelle Gedächtnis, in which Jan Assmann distinguishes a collective remembrance, “communicative” memory and “cultural” memory:

Communicative memory –biographical, factual, located within a generation of contemporaries who witness an event as adults, and who can pass on their bodily and affective connection to that event to their descendants.

Cultural Memory – memories from the areas, places, presented in buildings, landmarks etc; an institutionalized hegemonic archival memory.

Family and Memory• The language of the family is the language of the body;

nonverbal and non-cognitive acts of transfer happen within the family, often in the form of symptoms. Thus, the postgeneration wanted to assert its own victimhood.

• The children of those directly affected by collective trauma inherit a horrific, unknown, and unknowable past that their parents were not meant to survive.

• The scholarly and artistic work of the postgeneration makes it clear that the memories were mediated by public images, no matter how intimate the familial knowledge is.

The Holocaust and Feminist TheoryHirsch brings the examples of two works, Spiegelman’s Maus, and Sebald’s Austerlitz. While the two works have many similarities, Maus features a father and his son, while in Austerlitz feature a man and his mother. In Austerlitz, the protagonist is part of the “1.5 generation”, and so was a child survivor. While he remembers nothing from his childhood in Prague, he is obsessed with trying to find remnants of his mother.

Maus (1987)

Austerlitz (2001)

The Holocaust and Feminist Theory• This mother-child relationship and the severed bond between

them, prominent in many works, is a trope because of representing trauma at its most fundamental.

• It is important to “perceive and expose the functions of gender as a ‘pre-formed image’ in the act of transmission”.

• On one hand, dominant tropes such as this should be scrutinized carefully, as they can shift the attention from the rest of the traumatic event to just the familial loss. On the other hand, the postgeneration needs such tropes to rely on, because they are familiar and familial, and therefore more personal.

The End