The Expansion of the Kingdom of Amurru According to the Petrographic Investigation of the Amarna...

Transcript of The Expansion of the Kingdom of Amurru According to the Petrographic Investigation of the Amarna...

The Expansion of the Kingdom of Amurru According to the Petrographic Investigation ofthe Amarna TabletsAuthor(s): Yuval Goren, Israel Finkelstein and Nadav NaʾamanSource: Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 329 (Feb., 2003), pp. 1-11Published by: The American Schools of Oriental ResearchStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1357820 .

Accessed: 01/10/2014 23:01

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

The American Schools of Oriental Research is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extendaccess to Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Expansion of the Kingdom of

Amurru According to the Petrographic Investigation of the Amarna Tablets

YUVAL GOREN

Institute of Archaeology Tel Aviv University

P.O.B. 39040 Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv 69978

Israel ygoren @post.tau.ac.il

ISRAEL FINKELSTEIN

Institute of Archaeology Tel Aviv University

P.O.B. 39040 Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv 69978

Israel

NADAV NADAMAN Department of Jewish History

Tel Aviv University Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv 69978

Israel nnaaman@ post.tau.ac.il

A petrographic investigation of the Amarna tablets has been carried out by the authors since 1997. Over 300 tablets have so far been examined, including 14 letters sent by the rulers of Amurru. The petrographic data makes it possible to trace the ter- ritorial expansion of the kingdom of Amurru in the days of Abdi-Ashirta and Aziru. The Amurru letters fall into four distinct petrographic groups. The first includes two letters, which were sent from the mountainous area east of Tripoli, the core area of the kingdom. The second includes four letters, which were probably dispatched from the city of Ardata in the foothills. Five letters were sent from Tell CArqa. This seems to indicate that after consolidating his reign, Aziru transferred his capital to Irqata in the CAkkar Plain. Finally, three of Aziru's letters were sent from the Egyptian center of Sumur.

No Amurru letter was sent from the city of Tunip, which was also captured by Aziru. The analysis of the letter of the citizens of Tunip supports the identification of this impor- tant city at Tell CAsharneh northwest of Hama. This city was too remote from the main arena of Aziru's operations, which was focused on the Lebanese coast.

he early history of the kingdom of Amurru has been examined by many scholars ever since the discovery of the Amarna letters

(for detailed summaries, see Klengel 1969: 178- 299; Izre'el and Singer 1990; Singer 1991: 135-95). Amurru was initially a small highland kingdom sit- uated in the mountainous regions on the western slopes of Mount Lebanon and along Nahr el-Kebir. During the Amarna period, the kingdom gradually expanded. In its high days it covered the territory

between Tripoli on the Lebanese coast and the Middle Orontes area of western Syria. Amurru first emerged under a certain Abdi-Ashirta, who was able to expand his territory and conquer cities in his neighborhood. After his death the kingdom was led by his son Aziru, who continued his father's offen- sive and expanded the territory of his realm to the Orontes basin.

Several problems related to the "Amurru file" in the Amarna archive, such as the sequence of some

1

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2 GOREN, FINKELSTEIN, AND NADAMAN BASOR 329

of the events depicted by the letters, have been re- solved in scholarly research. Other issues, such as the location of the capital of Amurru's rulers at var- ious stages of their careers and the sequence of events in the time of Aziru, are still being debated. Another major question is the identification of the city of Tunip, mentioned in four of Aziru's letters (EA {=El Amarna} 161, 165-67) and in a letter sent by the citizens of Tunip to the Pharaoh (EA 59). Research on these problems has reached an impasse which may be broken only by new data.

These questions were put high on the agenda of our project of petrographic investigation of the Amarna letters, which has been ongoing since 1997. In the course of the project we conducted miner- alogical and chemical analyses of samples from over 300 tablets kept in museums in Berlin, London, Ox- ford, and Paris, including the tablets related to Amurru and Tunip.1 In this article we report the re- sults concerning the Amurru letters. Tunip will be discussed elsewhere.

METHOD

Various physical and chemical techniques are employed for analyzing the composition of ceramic artifacts. The former identify the minerals in the clay and temper and define the fabric of the sherd. The latter use diverse analytical techniques to measure the concentrations of the elements in the clay. In an- alyzing pottery, petrography is the physical method of choice, whereas neutron activation analysis (NAA) is the most commonly used chemical method. Petro- graphic analysis is particularly effective for exam- ining coarse, poorly fired ceramics, while NAA is generally considered to be more accurate for prove- nance determinations, being fully quantitative and thus more precise. Usually, petrography is applied to

a large number of items, and the results are used to select samples for further chemical analysis. When cuneiform tablets are analyzed, the sampling must be nondestructive and only restricted analyses can be applied. Consequently, chemical methods may seem more appropriate because of the smaller sam- ple that they require.

When the objective is to assign a provenance to an artifact, the quality of the interpretation depends on the availability of comparative materials. Clay types used to produce tablets are not necessarily the same as those from which vessels are manufactured. This may preclude the use of routine chemical pro- cedures in which a database containing the ele- mental composition of standard pottery from known sites is compared with the samples examined. Con- versely, petrography has the advantage of being in- dependent, since the results can be interpreted on the basis of detailed and usually available geological data (and comparative material from investigations of pottery assemblages). Therefore, petrography has been selected as a primary method for our research and has been applied on over 300 Amarna tablets.

Micropalaeontological study of the clay matrix was also deployed, using the foraminifera index to identify the age (and hence the possible geological formation and origin) of the clay. Foraminifera con- stitute one of the main groups of the unicellular organisms Protozoa. The main bulk live in marine environments, although there are also some inland and freshwater species. Marine foraminifera are di- vided into two main groups: those living in the water mass (planctonic) and those living on the sea floor (bentonic). Our identifications were made in the Geo- logical Survey of Israel. In many cases they either confirmed or oriented the petrographic and chemical interpretations into a narrower range of options.

CERAMIC ECOLOGY AND PETROGRAPHIC REFERENCES

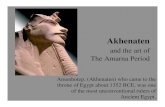

The area where the Amurru correspondence takes place may be enclosed by a schematic rectangle that lies between the Tripoli-Tartous line in the west, and the Tell Nebi Mend (Qedesh)-Aleppo line in the east (fig. 1). This area may be divided into four broad geographic and geologic units, each with a few subdivisions: (1) The coast: from Tripoli to Nahr el-CArqa; the CAkkar Plain from Nahr el-CArqa to Simerian; and from the northern limits of the CAkkar

'We wish to thank B. Salje and J. Marzahn from the Vorder- asiatisches Museum in Berlin; J. Curtis, S. Bowman, C. Walker, and A. Middleton from the British Museum; P. R. S. Moorey and H. Whitehouse from the Ashmolean Museum; and A. Caubet and B. Andr6-Salvini from the Mus6e du Louvre for their invaluable

help. The ICP analyses were made in the Geological Survey of Israel. This study was supported by the Center for Collaboration between Natural Sciences and Archaeology of the Weizmann Institute of Science, and the Fund for Internal Researches of Tel Aviv University. We thank I. Freestone, S. Gassner, M. Huges, A. Middleton, N. Porat, I. Segal, A. Shimron, and L. Smith for their useful comments on specific topics discussed in this article.

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2003 THE EXPANSION OF THE KINGDOM OF AMURRU 3

C)

Tell Asharneh (Tunip) SP

Hama

c..OTartous LI

Tell Kazel (Sumur)

AKKAR PLAIN Tell Nebi Mend

Tell 'Arqa (Qidshu) (Irqata)

Tripoli (Ullasa?) (laa Tell Ardeh

(Ardata)

THE MOUNTAINOUS REGION

0 30km

Fig. 1. Map of the land of Amurru with sites mentioned in the text.

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

4 GOREN, FINKELSTEIN, AND NADAMAN BASOR 329

TABLE 1. Petrographic Grouping of the Amurru Letters

Inclusions Sender's EA Matrix LB YB AM CT GQ LS MS VG VM QZ SF SP Location

60 LCC *** * * Mountains east 157 LCC * *** * of Tripoli

61 NGM *** ** *

62 NGM * ** * *** Ardata

156 NGM * *** *

159 NGM *** ** *

100 NGM *** ** *

161 NGM @ @

164 NGM @? @ @

169 NGM *** **** Irqata

170 NGM @ @ @ @

171 NGM *** ** **

165 QCC *** *** * ** * * 166 QCC @ @ @ Sumur

167 QCC *** *** * ** * *

168 LSP * ** ** *** Gaza

Legend Matrix types: LCC = Lower Cretaceous clay, PLM = Palaeogene marl, NGM = Neogene marl,

QCC = Quaternary coastal clay, LSP = Loess soil of southern Palestine. Inclusion types: LB = Lower basalt (Cretaceous), YB = Younger olivine basalt and dolerite

(Miocene-Pleistocene) and its derived minerals, AM = Amphiroa algae fossils (Pleis- tocene-Holocene), CT = chert, GQ = geode quartz, LS = limestone and calcite, MS = mollusk shell fragments, VG = volcanic glass, VM = vegetal material, QZ = quartz, SF = shale fragments, SP = serpentinized minerals.

Frequency: *** dominant, ** frequent, * scarce, @ undetermined (small samples).

up to Tartous. (2) The western mountainous range: the northern part of the Lebanon Mountains; the Tell Kalah volcanic area; Jebel Ansariyeh and the Shin volcanic plateau. (3) The inner valleys: the northern Beqac and the area of Homs; the Middle Orontes Valley and the Ghab. (4) The eastern mountainous range: the Salamiyeh Plateau and Jebel Zawiye. Different geological environments that are expected to yield different petrofabrics characterize each of these geographical units.

No petrographic work has been published so far on sites in the region, such as Tell Kazel, Tell CArqa, Hama, and Tell Mishrife. We were able to examine old collections of pottery from the region. When combined with the geological data, these collections supplied a reasonable dataset that allowed us to draw many important conclusions.

An important source of data is the geological mapping of the area, drawn first by Dubertret (1949;

1951a; 1951b) and later supplemented by others (Ponikarov 1964: sheets I-36-XXIV; I-37-XIX; Ponikarov et al. 1967; Kozlov, Artyemov, and Kalis 1966; Shatsky, Kazima, and Kulakov 1966; San- laville 1977; Sanlaville et al. 1993). On the large scale, it enables us to distinguish among various geographical zones within this broad area: the Oron- tes basin and the northern Beqac, Mount Lebanon, the Jebel Ansariyeh ridge, and the coastal plain. Within each area the lithological landscape is varie- gated enough to permit a higher resolution of differ- entiation among smaller units. Thus, the geological mapping supplied the basic information that can be correlated with the petrographic data obtained from the tablets.

In certain cases the geological literature supplies detailed information that may be used for even more precise identification of places mentioned in the Amurru correspondence. This applies, first and fore-

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2003 THE EXPANSION OF THE KINGDOM OF AMURRU 5

most, to the coastal plain, and especially to the CAkkar Plain and the mouth of Nahr el-Kebir (Sanlaville 1977; Kozlov, Artyemov, and Kalis 1966). Published data containing micropalaeontological identifications, combined with very detailed geological literature concerning the lithostratigraphy of the Palaeogene (Luterbacher 1986; Krasheninnikov, Golovin, and Miravyov 1996) and the Neogene (Dubertret 1945; Buchbinder 1975), supply enough information to set the clay types used by the scribes in their chrono- stratigraphic context.

RESULTS

Petrographically, the Amurru letters can be di- vided into four groups (see table 1). In other words, they were dispatched from four different places.2

Letters Sent from the Mountainous Area East of Tripoli

The first group of letters to be discussed includes EA 60 and 157. The former was sent by Abdi-Ashirta and the latter by Aziru.

The matrix of these tablets is argillaceous and devoid of carbonate minerals, yellow to yellowish- orange in plane-polarized light (PPL) with speckled to striated b-fabric3 and strong optical orientation. It is mottled with common bodies of clay in various colors sizing up to 250 [im, seemingly the alteration products of various minerals, constituting nearly 5 percent of the matrix. These include yellow through orange to dark red clay, frequently optically active, tuff and iddingsite. Opaque minerals, usually angu- lar at the finer fraction and subrounded to spherical at the coarser, are also widespread, forming about 3-4 percent of the matrix, sizing up to 60-70 pm. Some of the larger opaque or nearly opaque particles are oolitic. Silt, essentially of quartz but with acces-

sory plagioclase (sometimes twinned), forms approx- imately 2-3 percent of the matrix. Dark reddish-tan, ferruginous shales that are frequently microlami- nated and silty (approximately 2-3 percent) appear as massive bodies reaching millimeter size. Other shale fragments are of yellowish clay, with speckled b-fabric.

The inclusions are composed of the following:

* Basaltic minerals: Dominant, including rounded globules of glassy phases, yellow to orange in PPL, fibrous with undulose extinction in crossed polarizers, sizing up to 100 lim. These are most likely serpentinized minerals. Few clinopyroxene crystals and very few iddingsite particles also appear.

* Alkali basalt: A few fragments of finely crystal- line alkali basalt (up to 350 [pm) of trachytic tex- ture with elongated and oriented plagioclase laths. The pyroxene is partly or entirely serpentinized.

* Vegetal material: These include fragments of plant tissues.

The petrographic features of EA 60 and 157 are characteristic of Lower Cretaceous clay and shales, with many of the attributes unique to these forma- tions. This petrographic group has been discussed in detail by Greenberg and Porat (1996) and Goren (1992; 1995; 1996). The presence of basalt and/or tuff in the inclusions suggests a nearby exposure of the basal Lower Cretaceous volcanics, whereas the presence of diversified shales points to the use of shales from the Lower Cretaceous sandstone units. Trachytic textures and an alteration of the olivine into chlorite characterize the basalts of the Lower Cretaceous section (Mimran 1972; Amiran and Po- rat 1984), as opposed to the Miocene-Pleistocene basalts (to be discussed below in the Irqata section).

The lower formations of the Levantine Lower Cretaceous lithological section outcrop widely in Mount Lebanon, along the slopes of Mount Hermon and less frequently in the Anti-Lebanon. Geologi- cally, they are included in the Lower Cretaceous basal unit, namely the Gras de Base or Cl units (e.g., Dubertret 1949), recently termed the Chouf Sandstone Formation (Walley 1997).

The presence of basalt and pyroclastic material among the inclusions may be related to the proxim- ity of the clay source to an exposure of the Lower Cretaceous or Upper Jurassic volcanic complex (ba- salte cr6tac6, equivalent to the Tayasir volcanics of Israel). These layers are widely exposed in Mount

2The only Amurru letter that does not belong to any of the four groups discussed below is EA 168. It belongs to a group of tablets that were made in the southern coastal plain, most proba- bly at the important Egyptian administrative center of Gaza (Goren, Finkelstein, and Na'aman in press).

3b-fabric: birefringent fabric, the optical behavior of the clay minerals within the matrix when they are found in parallel align- ment, hence causing the matrix to behave as a birefringent matter between crossed polarizers. Speckled b-fabric: random birefrin- gent zones of a few microns in size. Striated b-fabric: elongated birefringent streaks (after Whitbread 1995: 382-83).

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

6 GOREN, FINKELSTEIN, AND NADAMAN BASOR 329

Lebanon. The distribution of the Aptian formations in Lebanon is limited to a belt that extends between Mount Hermon in the south and the CAkkar Plain in the north, covering the upper parts of Mount Leba- non and their slopes (Dubertret 1962). A narrow stripe of this formation is exposed along this ridge, from Merj CAyyun northeastward. The largest expo- sure appears in the area between Zahle in the Beqac and Aaley on the western slopes of Mount Lebanon. In the Anti-Lebanon, a stripe is exposed between Rashiya el-Fukhar and the Zebedani. However, the volcanics appear in significant exposures only in Mount Lebanon, north of the Beirut-Zahle line.

We therefore suggest that the origin of these two tablets should be sought in the mountainous area southeast of the cAkkar Plain, but not in or around it. Lower Cretaceous exposures, including outcrops of the basalte cr6tac6, occur along the slopes of the Jebel Neghas, about 10 km southeast of Arde (Du- bertret 1949).

In sum, the mountainous area east of Tripoli is the most likely source for the clay of these two tablets.

Letters Sent from Ardata

This group of letters includes EA 61 and 62, which were sent by Abdi-Ashirta, and EA 156 and 159, which were dispatched by Aziru.

The matrix of these tablets is carbonatic, light yellowish-tan in PPL, containing infrequent badly preserved foraminifers and more commonly their fragments. It is rather silty (about 2 percent) and very rich in opaque iron minerals that appear at a range of sizes from a few micrometers to about 30- 40 gm. Under higher magnifications (> 200X) the matrix is fibrous, with speckled b-fabric and weak optical orientation. Foraminifera are abundant in the matrix; they include the following benthonic and planctonic genii: Bryozoa, Bulimina, Catapsydrax, Globigerina, Globigerinoides, Globorotalia, and Or- bulina. Apart from occasionally added vegetal mate- rial, the inclusions appear to be naturally detrital within the reworked clay of the matrix and not inten- tionally mixed by the artisan. These include frequent (and sometimes dominant) limestone and calcite as rounded grains, sizing up to around 250 rtm. Quartz appears as a secondary component, usually as sub- angular grains sizing up to 100 rim.

By its petrofabric and palaeontology, the matrix of these tablets indicates the use of Neogene marl.

Such marls, dating to the Miocene or the Pliocene, do not appear in the Levant south of the Lebanese coast. In Lebanon, their outcrops are restricted mainly to exposures east and south of Tripoli (Dubertret 1951b) and to a lesser extent in patches between Tripoli and Beirut. Notable among them is the out- crop of Nahr el-Awdeh, including the site of Tell Arde (ancient Ardata), which is the only significant mound near any of these exposures that is found in an entirely sedimentary area (as opposed to Irqata, to be discussed below). Tell Arde is a medium-sized site of about 3.5 ha located 8 km from the coast; it overlooks the area east of Tripoli (for the site, its location, and trial excavations, see Salam6-Sarkis 1972; 1973; Izre'el and Singer 1990: 119-20, with earlier literature).

Because Tell Arde is situated over 12 km down- hill from the nearest Lower Cretaceous exposure of Mount Lebanon (see the first group above), we sug- gest a distinction between the group of tablets de- scribed here, which was probably sent from Ardata, and the first group discussed above (EA 60 and 157), which was dispatched from the neighboring mountainous area.

Letters Sent from Irqata

This group includes EA 161, 164, and 171, which were sent by Aziru; EA 169, possibly dispatched by Bacluya, Aziru's elder son (Na'aman 1996: 256); and EA 170, sent from Bacluya and Bet-ili to Aziru in Egypt.4 Significantly, this group also includes EA 100, which was sent by the elders of Irqata, identi- fied with Tell CArqa in the CAkkar Plain-the most important Bronze Age mound between Tell Kazel (Sumur) and Tripoli (possibly the location of Ul- lasa;5 for the excavations of Tell CArqa, see Thal- mann 1991, with earlier literature).

The matrix of these tablets is carbonatic, yellow- ish-tan in PPL, rich in cloudy, badly sorted carbon- ate micrite (about 20 percent). It is extremely rich (approximately 7 percent) in opaque to reddish-tan iron minerals that appear at a range of sizes from a

4Several scholars suggested that the same scribe wrote EA 169 and 170 (Moran 1992: 257, n. 1, with additional references). The petrographic data seems to support this hypothesis, although the sample size of EA 170 does not allow a semi-quantitative analysis of the inclusions.

5Galling 1954: 100; for other suggestions see Klengel 1970: 12, 25-26 n. 32; Liverani 1998: 201-2 n. 115. For Late Bronze remains in Tripoli, see Salam&-Sarkis 1973: 94.

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2003 THE EXPANSION OF THE KINGDOM OF AMURRU 7

few micrometers to about 30-40 Vtm, which are an- gular; the translucent minerals tend to be spherical and rounded. Iron minerals also appear as infillings within foraminifers. EA 169 and 171, the best and largest samples belonging to this petrographic group, feature abundant benthonic and planctonic foramin- ifera of the following genii: Bolivina, Bulimina, Glo- bigerina, Globigerinoides, and Globorotalia; they all belong to the Neogene to Holocene ages. The inclusions are composed of moderately sorted sand, dominated by alkali olivine basalt and dolerite, sizing up to 1.2 mm. Secondary components include sub- rounded, micritic, and sparitic limestone, up to 800

gtm in size. Added vegetal material is uncommon.

In terms of the clay used, this group presents marl with typical cloudy micrite fragments that densely occupy it. The inclusions are typified by a signifi- cant basic igneous content, usually of basalts and sel- dom of dolerite, together with limestone and some quartz.

The lithological combination that is presented here may be limited specifically to the CAkkar Plain near the Nahr el-Kebir channel, the only area where Pliocene marine deposits and volcanics appear to- gether (Kozlov, Artyemov, and Kalis 1966: 33). The only significant site in this area is Tell CArqa.

Tell CArqa is situated in the southern flank of the CAkkar Plain, near Nahr el-CArqa which drains the mountainous area to the southeast of the plain. The site is located on a plain of Pliocene argils and marl, near the lower terrace of quaternary colluvium that collects its materials from the Turonian and Cenomanian calcareous formations and the volcanic terrain east of Halba (Sanlaville 1977: 25, 243-80, map 1). The Nahr el-CArqa channel collects sediments from the plateau to the east and the plains north and south of Tell CArqa. In these areas, Cenomanian- Turonian limestone series, Senonian chalk and chert, Lower Cretaceous sandstones and marls, and Juras- sic limestones are exposed. To the northeast, Pliocene volcanics contribute the basalt component.

Based on these petrographic traits and on the fact that EA 100, which belongs to this petrofabric, was sent by the elders of Irqata, we are inclined to assign the tablets of this group to Tell CArqa.

Letters Sent from the Egyptian Center of Sumur

This group includes EA 165, 166, and 167, which are identical petrographically and were sent by Aziru. It also includes EA 96, the letter of an Egyp-

tian army commander to Rib-Hadda of Gubla, and EA 103, a letter sent by Rib-Hadda to the Pharaoh.

The matrix of these tablets is argillaceous, carbon- atic, orange-tan to tan in PPL with scarce foraminifers. Opaque minerals are rather common (approximately 2 percent), sizing up to 100 Vtm. Quartz silt occurs (approximately 1 percent) together with a smaller amount of plagioclase. The carbonate crystals within the matrix are dense (15 percent), usually sizing around 10 gm but occasionally reaching 20 gim-30

gtm. The matrix includes the following foraminifera:

Brizalina spathulata, Globigerina, and Globorotalia; they all belong to the Pliocene to Pleistocene age. The inclusions are composed of frequent rounded fragments of fossiliferous coastal limestone (beach- rock) and more commonly separate fossils, sizing up to 650 [tm. The fossils consist predominantly of articulated fragments of the calcareous corallinean algae Amphiroa, together with some mollusk shell fragments. Chert is also common, usually appearing as rounded, smoky to brown stained replacement chert with local intergrowth of chalcedony, reach- ing millimeter size. Subrounded to subangular frag- ments of micritic limestone with common localized brownish staining, and subangular to subrounded quartz grains (including fragments of geode quartz with common liquid and mineral inclusions) appear as secondary components. Angular grains (up to 380 gim) of serpentinized mineral crystals, most likely alteration products of mafic minerals (pyroxene or olivine), appear in minor quantities.

In the Levantine coast corallinean algae of the genus Amphiroa occur in Quaternary bioclastic sed- iments of the Pleshet, Hefer, and Kurdane formations of Israel (Buchbinder 1975; Almagor and Hall 1980; Sivan 1996). So far no equivalent geological termi- nology has been formalized for the coast of Lebanon, but similar traits are recorded from the contemporary and analogous beachrocks and sands found there (Sanlaville 1977: 161-77; Almagor and Hall 1980; Walley 1997). In the eastern Mediterranean this alga appears only in beach sediments dating from the Pleistocene and onward (Buchbinder 1975). On the basis of its dominance within the inclusions of EA 165-67, we can suggest that this group should be related with Quaternary beach deposits.

The other components represent different units within the Levantine lithostratigraphic section. Chert is almost always related to formations of Santonian- Campanian or Eocene age, and geode quartz is typ- ical of the Cenomanian-Turonian transition. The

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8 GOREN, FINKELSTEIN, AND NAAMAN BASOR 329

igneous mafic minerals (serpentine, olivine, pyrox- ene) and the volcanic rock fragments that appear as detrital but rather large grains can represent Pliocene- Pleistocene basalt flows, or earlier Lower Cretaceous basalts that are generally scarcer in extent.

In sum, the source of the materials for the tablets of this group should be sought in an area where ex- posures of chalk appear together with Pleistocene-to- recent beach deposits of mainly calcareous character, chert and occasional basalt exposures. While in the southern Levant the coastal sediments are dominated by quartzitic sand, which originally comes from the Nile, in the northern coast of Israel (from Akko northward) this type of sand diminishes and the sediment becomes increasingly calcareous. A sys- tematic examination of thin sections made from Ho- locene coastal sand from various localities along the coast indicates that quartz is the dominant compo- nent as far north as Haifa Bay. North of Akko the beach sand is composed almost exclusively of car- bonates (Nir 1989: 12-15). This implication is sig- nificant, because it indicates that our samples should be related a priori to the coastal area north of Akko. Furthermore, Pliocene marine deposits appear only on the Lebanese coast.

Other components within the inclusion assem- blage may further limit the possibilities. In the Le- vantine lithostratigraphy, chert is related either with Senonian or Eocene exposures. Such exposures are found predominantly between Tyre and Sidon, and again north of Tripoli. When serpentine and weath- ered volcanic rock fragments appear, they can be linked to an inland area where volcanic rock types are exposed. The only area where Quaternary beach de- posits, Senonian or Eocene chert, and mafic minerals of volcanic origin may appear together is the coastal area of the CAkkar Plain between Tripoli and Tartous. The mafic minerals were most likely dragged there from the basaltic flows of Nahr el-Kebir, where vol- canic elements are embedded in the local sediments. Therefore, the origin of the tablets belonging to this group should be sought in the area of the cAkkar Plain, not far from the seashore.

Considering the archaeological evidence, the only significant site in this area, where Late Bronze re- mains are reported, is Tell Kazel. The area to its north is characterized by Pliocene brown alluvial soils, limestone, chert and basalt pebbles, and Qua- ternary marine deposits (Kozlov, Artyemov, and Ka- lis 1966: 43-44; Sanlaville 1977: 270-84, map 1).

Basalts appear on the ridges east of the plain, and their derived minerals and alteration products are drained by Nahr el-Abrash which passes near the site. Thus, the combination of all the petrographic elements, the textual evidence, and the archaeologi- cal background point to Tell Kazel as the most likely origin of this group of tablets. Tel Kazel is widely accepted as the location of the ancient city of Sumur (for the excavations of the site, see Badre et al. 1990; 1994; for the location and history of Sumur, see Klengel 1995).

This conclusion is supported by EA 96, written by an Egyptian army commander, and EA 103, sent by Rib-Hadda of Gubla. Both belong to this group petrographically, and both include textual evidence for having been dispatched from Sumur.

HISTORICAL CONCLUSIONS

The petrographic data makes it possible to trace the political developments in Amurru and its territo- rial expansion in the time of the Amarna correspon- dence. The earliest letters, including those of Abdi- Ashirta and the early letters of Aziru, originated from two closely related locations: the mountainous area east of Tripoli and the city of Ardata in the foot- hills east of Tripoli. We therefore suggest that in the early days of the Amarna period, the seat of Abdi- Ashirta was located in the mountainous area east of Tripoli, and that this was the core area of the king- dom of Amurru. No significant Late Bronze site has been recorded thus far in this area. EA 60 and 157 could have been sent from a small mountain strong- hold-possibly the hometown and place of origin of the family. This confirms the notion that Amurru was initially a small highland kingdom situated on the slopes of Mount Lebanon, on both sides of Nahr el-Kebir, and inhabited by farmers, pastoral groups, and uprooted elements (Liverani 1965a; 1965b; Klengel 1969: 245-53; Mendenhall 1973: 130-35).

EA 61, 62, 156, and 159 were sent from the city of Ardata (Tell Arde), which was located in the foot- hills, not too far from the Egyptian harbor-center of Ullasa (modern Tripoli). Initially, Ardata was governed by its own ruler (EA 139:15; 140:12). It was then captured by Abdi-Ashirta (EA 88:5; see EA 75:30-31) and held by his heir, Aziru, in his early years (EA 104:10). In light of the petro- graphic analysis, we suggest that Ardata was the

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2003 THE EXPANSION OF THE KINGDOM OF AMURRU 9

capital of Amurru during the later years of Abdi- Ashirta and the early years of Aziru. The fact that both Abdi-Ashirta and Aziru dispatched letters from both the mountainous area and Ardata indicates that the Amurru correspondence in the Amarna archive starts after the takeover of Ardata.

EA 161, 164, 169, 170, and 171 were sent from Irqata (=Tell CArqa). It seems that after consolidating his reign, Aziru transferred his capital to Irqata, which was initially governed by a local ruler named Aduna. He was murdered at the initiative of Abdi- Ashirta (EA 75:32-33; 139:15; 140:10) who took possession of the city (EA 62:13, 17, 22; 88:6). After the death of Abdi-Ashirta, the elders of Irqata sent a letter to the Pharaoh in which they explained their deeds and expressed their loyalty to Egypt (EA 100; for interpretation of the letter, see Moran 1992: 173 n. 6). The loyalty of Irqata to Egypt is also mentioned in a letter sent by Rib-Hadda of Gubla (Byblos) at roughly the same time (EA 103:11-13, 34-36). How- ever, shortly afterward Irqata was seized by Aziru. This is indicated by EA 109:9-15: "Now the sons of Abdi-Ashirta . . have taken the cities of the king and the cities of his mayors, just as they please; they are the ones that [took Irqa]ta (sic!) for themselves.6 And you did nothing about their [actions] when you heard that they have taken Ullasa." The capture of Irqata by Aziru is confirmed by the letters of Ili- rapih, Rib-Hadda's successor at Gubla (EA 139:15; 140:10).

Irqata served as Aziru's capital until the end of the Amarna period. Letter 170, sent by Aziru's brother and son while Aziru was in Egypt, was dispatched from this city. EA 161-probably Aziru's latest let- ter written after his return from Egypt and after his conquest of Tunip-was also sent from Irqata.

According to the "General's letter," Irqata func- tioned as the headquarters of the army that held the territory of the kingdom of Amurru against an im- pending attack of Egyptian troops (Izre'el and Singer 1990: 117-21). Ardata was probably an advance post of the general's troops, thus located near the southern border of Amurru. The letter was written not long after the end of the Amarna period, thus reflecting

the post-Amarna stage in the political development of the kingdom of Amurru. It is not clear whether Irqata was still Amurru's capital at that time, or whether Aziru moved his capital to another, more secure place. The answer to this question might be found in future petrographic research, when the later letters of Amurru discovered in Ugarit and Hattusha will be analyzed.

EA 165, 166, and 167 were sent by Aziru from Sumur.7 These three letters were written at the same time to the Pharaoh and to two high officials in his court. Aziru might have arrived there to meet Hatip, the Egyptian messenger, and on that occasion wrote these letters. Soon afterward he went to Egypt, ac- companied by Hatip, probably by a ship that sailed from Sumur (see EA 168). The paucity of letters sent from Sumur indicates that although Aziru con- quered the city, he avoided turning it into his perma- nent seat. Aziru might have visited Sumur on other occasions (e.g., the situation described in EA 161: 11-16), but his letters were written from his resi- dence at Irqata.

It is noteworthy that no Amurru letter was sent from Tunip. Although Aziru captured the city, at least in the Amarna period it did not serve as his capital. The petrographic study of the Amarna let- ters confirms the identification of Tunip with Tell CAsharneh northwest of Hama (Courtois 1973: 55 n. 5; Klengel 1995; Liverani 1998: 298 n. 42; Na'aman 1999; Goren, Finkelstein, and Na'aman in press). Tunip was therefore too remote from the ma- jor arena in which Aziru operated. For military and economic reasons, the coast of Lebanon remained his main concern. The post-Amarna "General letter" fully illustrates this.

In sum, the petrographic analysis proves to be an indispensable tool for analyzing certain aspects of the history of Amurru that cannot be approached by conventional historical research. It enables us to es- tablish the sequence of political centers of the king- dom of Amurru and its development from a small mountainous entity, ruled from a highland strong- hold, to a large territorial kingdom extending up to the Orontes Valley, whose capital remained near the coast, not far away from the dynasty's hometown and place of origin.

6Moran (1992: 183) and Liverani (1998: 212) restored in line 12 [Arda]ta. But according to EA 104:10 Ardata was already in the hands of Aziru. Restoring it [Irqa]ta is in line with EA 103:11-13, 34-36, which indicates that Irqata fell into the hands of Aziru at a somewhat later time.

7Izre'el and Singer (1990: 138; Singer 1991: 152) proposed that the three letters were sent from Tunip.

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

10 GOREN, FINKELSTEIN, AND NADAMAN BASOR 329

REFERENCES

Almagor, G., and Hall, J. K. 1980 Morphology of the Continental Margine of

Northern Israel and Southern Lebanon. Israel Journal of Earth Sciences 29: 245-52.

Amiran, R., and Porat, N. 1984 The Basalt Vessels of the Chalcolithic Period

and Early Bronze Age I. Tel Aviv 11: 11-19. Badre, L.; Gubel, E.; al-Maqdissi, M.; and Sader, H.

1990 Tell Kazel, Syria: Excavations of the AUB Mu- seum, 1985-1987, Preliminary Report. Berytus 38: 9-124.

Badre, L.; Gubel, E.; Capet, E.; and Panayot, N. 1994 Tell Kazel (Syrie), Rapport pr61iminaire sur les

4e-8e campagnes de fouilles (1988-1992). Syria 71: 259-346.

Buchbinder, B. 1975 Stratigraphic Significance of the Alga Amphi-

roa in Neogene-Quaternary Bioclastic Sedi- ments from Israel. Israel Journal of Earth Sciences 24: 44-48.

Courtois, J.-C. 1973 Prospection archeologique dans la moyenne

vall6e de l'Oronte (El Ghab et Er Roujd-Syrie du nord-ouest). Syria 50: 53-99.

Dubertret, L. 1945 Carte geologique au 50.000e feuille de Ham-

diye. Beirut: Ministere des Traveaux Publics. 1949 Carte geologique au 200.000e feuille de Trip-

oli. Beirut: Ministere des Traveaux Publics. 1951a Carte ge'ologique au 50.000e feuille de Bey-

routh. Beirut: Ministere des Traveaux Publics. 1951b Carte geologique au 50.000efeuille de Tripoli.

Beirut: Ministere des Traveaux Publics. 1962 Carte geologique Liban, Syrie et bordure des

pays voisins. Paris: Mus6e National d'Histoire Naturelle.

Galling, K. 1954 Das Deutsche Evangelische Institut fiir Alter-

tumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes im Jahre 1953. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Pallis- tina-Vereins 70: 97-103.

Goren, Y. 1992 Petrographic Study of the Pottery Assemblage

from Munhata. Pp. 329-60 in The Pottery As- semblages of the ShaCar Hagolan and Rabah Stages of Munhata (Israel), by Y. Garfinkel. Les Cahiers du Centre de recherche frangais de Jerusalem 6. Paris: Association Pal6orient.

1995 Shrines and Ceramics in Chalcolithic Israel: The View through the Petrographic Micro- scope. Archaeometry 37: 287-305.

1996 The Southern Levant in the Early Bronze Age IV: The Petrographic Perspective. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 303: 33-72.

Goren, Y.; Finkelstein, I.; and Na'aman, N. In press Inscribed in Clay: Petrographic Investigation

of the Amarna Tablets. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University.

Greenberg, R., and Porat, N. 1996 A Third Millennium Levantine Pottery Produc-

tion Center: Typology, Petrography, and Prov- enance of the Metallic Ware of Northern Israel and Adjacent Regions. Bulletin of the Ameri- can Schools of Oriental Research 301: 5-24.

Izre'el, S., and Singer, I. 1990 The General's Letter from Ugarit: A Linguis-

tic and Historical Reevaluation of RS 20.33 (Ugaritica V, No. 20). Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv University.

Klengel, H. 1969 Geschichte Syriens im 2. Jahrtausend v.u.Z.,

Vol. 2: Mittel- und Siidsyrien. Deutsche Akad- emie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Institut fiir Orientforchung, Ver6ffentlichung 70. Berlin: Akademie.

1970 Geschichte Syriens im 2. Jahrtausend v.u.Z., Vol. 3: Historische Geographie und allgemeine Darstellung. Deutsche Akademie der Wissen- schaften zu Berlin, Institut fuir Orientforchung, Ver6ffentlichung 40. Berlin: Akademie.

1995 Tunip und andere Probleme der historischen Geographie Mittelsyriens. Pp. 125-34 in Immi- gration and Emigration within the Ancient Near East, eds. K. van Lerberghe and A. Schoors. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 65. Leuven: Peeters.

Kozlov, V. V.; Artyemov, A. V.; and Kalis, A. E 1966 The Geological Map of Syria, Scale 1:200,000,

Sheets I-36-XVIII, 1-37, XIII (Trablus, Homs), Explanatory Notes. Moscow: Technoexport.

Krasheninnikov, V. A.; Golovin D. I.; and Miravyov, V. I. 1996 The Paleogene of Syria-Stratigraphy, Lithol-

ogy, Geochronology. Geologisches Jahrbuch 86: 3-136.

Liverani, M. 1965a Implicazioni sociali nella politica di Abdi-

Ashirta di Amurru. Rivista degli Studi Orien- tali 40: 267-77.

1965b I1 fuoruscitismo in Siria nella tarda eta del bronzo. Rivista Storica Italiana 77: 315-36.

1998 Le lettere di el-Amarna 1-2. Brescia: Paideia.

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2003 THE EXPANSION OF THE KINGDOM OF AMURRU 11

Luterbacher, H. P. 1986 Paleogene. Paper presented at a conference on

Planktonic Foraminifera as Stratigraphic Tools: Workdesk on Planktonic Foraminifera, Febru- ary 17-22, 1986, TUibingen.

Mendenhall, G. E. 1973 The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the

Biblical Tradition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University.

Mimran, Y. 1972 The Tayasir Volcanics, a Lower Cretaceous

Formation in the Shomeron, Central Israel. Geological Survey of Israel Bulletin 52: 1-9.

Moran, W. L. 1992 The Amarna Letters. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University. Na'aman, N.

1996 Ammishtamru's Letter to Akhenaten (EA 45) and Hittite Chronology. Aula Orientalis 14: 251-57.

1999 Qarqar = Tell CAsharneh. Nouvelles Assyri- ologiques Brt'ves et Utilitaires 1999, no. 4: 89- 90.

Nir, Y. 1989 Sedimentological Aspects of the Israel and

Sinai Mediterranean Coasts. Jerusalem: Geo- logical Survey of Israel (Hebrew).

Ponikarov, V. P., ed. 1964 The Geological Map of Syria, 1:200,000 (20

sheets with geological cross sections and ex- plenatory notes). Moscow: Technoexport.

Ponikarov, V. P.; Kazmin V. G.; Mikhailov, I. A.; Razva- liayev, A. V.; Krasheninnikov, V. A.; Kozlov, V. V.; Sulidi-Kondratev, E. D.; Mikhailov, K. Y.; Kulakov, V. V.; Faradzhev, V. A.; and Mirzayev, K.

1967 The Geology of Syria, Explanatory Notes on the Geological Map of Syria, Scale 1:500,000, Vol. 1: Stratigraphy, Igneous Rocks and Tec- tonics. Damascus: Syrian Arab Republic, Min- istry of Industry, Department of Geological and Mineral Research.

Salam6-Sarkis, H. 1972 Ardata-Ard6 dans le Liban-Nord: Une nouvelle

cite Canan6enne identifi6e. Milanges de l'Uni- versiti Saint-Joseph 47: 123-45.

1973 Chronique archeologique du Liban-Nord II: 1973-1974. Bulletin du Musee de Beyrouth 26: 91-102.

Sanlaville, P. 1977 Etude ge'omorphologique de la region littorale

du Liban. Section des etudes g6ographiques 1. 2 vols. Beirut: Universit6 Libanaise.

Sanlaville, P.; Besangon, J.; Copeland, L.; and Muhe- sen, S.

1993 Le Pale"olithique de la valled" moyenne de l'Oronte (Syrie): Peuplement et environnement. BAR International Series 587. Oxford: Tempus Reparatum.

Shatsky, V. N.; Kazima, V. G.; and Kulakov, V. V. 1966 The Geological Map of Syria, Scale 1:200,000,

Sheets I-37-XIX, 1-36, XXIV, Explanatory Notes. Moscow: Technoexport.

Singer, I. 1991 A Concise History of Amurru. Pp. 134-95 in

Amurru Akkadian: A Linguistic Study, Vol. 2, by S. Izre'el. Harvard Semitic Studies 41. Atlanta: Scholars.

Sivan, D. 1996 Paleogeography of the Galilee Coastal Plain

during the Quaternary. Report of the Geological Survey of Israel GSI/11/96; PhD dissertation, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Geological Survey.

Thalmann, J.-P. 1991 L'Age du Bronze 'a Tell CArqa: bilan et perspec-

tives (1981-1991). Berytus 39: 21-38. Walley, C.

1997 The Lithostratigraphy of Lebanon, A Review. Lebanese Science Bulletin 10: 81-108.

Whitbread, I. K.. 1995 Greek Transport Amphorae: A Petrological and

Archaeological Study. Fitch Laboratory Occa- sional Paper 4. Athens: British School at Athens.

This content downloaded from 220.233.185.93 on Wed, 1 Oct 2014 23:01:40 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions