The Effectiveness of Classroom-Based Supplementary Video

Transcript of The Effectiveness of Classroom-Based Supplementary Video

THE EFFECTIVENESS OF CLASSROOM-BASED SUPPLEMENTARY VIDEO PRESENTATIONS IN SUPPORTING EMERGENT LITERACY

DEVELOPMENT IN EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION

* Associate Professor, Department of Instructional & Learning Technology College of Education, Sultan Qaboos University. ** Assistant Professor, Department of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Education, South Valley University, Egypt.

ABSTRACT

This study investigated the impact of supplementary video presentations in supporting young children's emergent

literacy development. Videos were produced by teachers using prototype software developed specifically for the

purpose of this study. The software obtains media content from a variety of resources and devices, including webcam,

microphone, PowerPoint slides, drawing board, and typing board in a simplified manner. Videos were supplemented to

children who were identified as at risk to be viewed at home individually or with their parents. Participants were teachers

and children in a full-day kindergarten in the Sultanate of Oman. Teacher Rating of Oral Language and Literacy (TROLL)

scale and parent interviews were administered to measure the literacy skills and development of children in early

childhood classrooms, and to understand children's reactions to the use of classroom video presentations respectively.

The results of TROLL indicated that no improvement had happened in the total score of oral language and literacy of the

treatment group children (12) compared to the control group children. However, the treatment group children's

language use was improved significantly. Results from interviews showed that children liked video presentations

prepared by their teachers, and parents found these videos useful for their children's literacy development.

Keywords: Early Childhood Education, Emergent Literacy, Video Presentation, Multimedia.

ALAA SADIK * KHADEJA BADR **

By

INTRODUCTION

Although literacy development occurs throughout a

lifetime, the early childhood years are crucial for laying a

foundation for language learning and later school

success (Invernizzi, Landrum, Teichman, & Townsend,

2010; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 2002). Therefore,

experiences in early childhood classrooms and at home

contribute significantly to a childs language and

emergent literacy abilities. Researchers in the field agree

that emergent literacy is made up of several key skills.

These skills of emergent literacy are phonemic awareness,

word recognition, concepts about print, alphabetic

principle, and comprehension. Phonemic awareness, for

example, is recognized as an understanding that speech

is composed of units, and the ability to perceive and

manipulate the units of speech (Gunn, Simmons, &

Kameenui, 2000).

The rapid development in educational computer

applications has offered new and efficient tools in

teaching emergent literacy (Parette, Hourcade, Dinelli

and Boeckmann, 2009). Multimedia in particular is being

used with increasing frequency in early childhood

education to develop children's literacy skills. Presentation

software, for example, are increasing in popularity and

providing powerful tools for the creation of learning

materials and accessible information in several formats.

When used appropriately in early childhood education,

these tools can support and extend traditional literacy

classes in valuable ways (National Association for the

Education of Young Children, 1996).

Microsoft PowerPoint, as a multimedia authoring and

presentation tool, has become the dominant

presentation tool in early childhood settings because it is

both readily available and easy-to-use by teachers

(Grabe & Grabe 2007). PowerPoint allows teachers to

create and manipulate presentations in a wide variety of

contexts that can enhance a childs interest and

RESEARCH PAPERS

21li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

engagement (Mills & Roblyer 2006). It helps teachers to

clearly identify the main points of a lesson or activity while

still providing the details through presentation (Loisel &

Galer, 2004). In addition, teachers can incorporate

multiple types of media formats (e.g., clipart, photo,

drawing, sound, and video) that cannot be easily

integrated together into one single medium. Young

learners are also attracted to PowerPoint because of the

graphical, transactional, aesthetic, and interactive

features it provides. Chiasson & Gutwin (2005) believe that

children's goals while learning with computers are

typically education or entertainment rather than

productivity.

PowerPoint and emergent literacy development

In a series of studies on using PowerPoint to support the

development of learners in early childhood education,

Parette and his colleagues at Illinois State University tell us

that well-designed and teacher-guided PowerPoint

presentations help young children, particularly those at

risk for reading difficulties, to build confidence and to work

and feel comfortable with the lesson format the teacher

has designed for them (Parette, Blum, Boeckmann &

Watts, 2009; Parette, Quesenberry & Blum, 2010). Parette

and his colleagues also conducted a series of studies

focused on the use of PowerPoint in teaching emergent

literacy skills for young children. They found that the

popularity of PowerPoint and availability of LCD digital

projectors greatly enhance the group teaching potential

of PowerPoint presentations. They engage children in

various learning activities that contribute to the

development of their vocabulary meaning skills,

phonological awareness, comprehension of stories,

alphabet and print awareness, and story sense (Parette,

Wojcik, Stoner & Watts, 2007; Parette, Hourcade,

Boeckmann & Blum, 2008).

For example, the teacher might use the animation

features to make slides more engaging for children, and

control the appearance of each letter in a word so that it is

isolated and can be linked with the sound that

corresponds to it. In addition, a single letter could appear

on the slide, followed by the sequential appearance of

other letters, until an entire word is created, illustrating left-

to-right sequencing in the construction of words and the

reading process (Parette, Blum & Watts, 2009).

However, although there is interest in the utility of

PowerPoint to teach emergent literacy skills for young

learners, it is only used by the teacher inside classrooms,

and it needs to be paired with the use of an LCD projector

and large screen. In other words, PowerPoint slide content

and visual features are not a substitute for the guidance a

teacher should deliver. If young learners are not seeing

and listening to the teacher, then learning from the slides

at home or in isolation will be less valuable or impossible.

Research indicated that self-regulation plays a role in

young learner interaction with learning materials which

requires considerable knowledge, skill, and motivation.

According to Zimmerman (1990, 2002), the key emphasis

of self-regulation (self-control, self-satisfaction, self-

observation, self-judgment, and self-evaluation) is on how

learners manage their time and control the environment

in which they engage in learning. Boekaerts (1995)

indicated that learners not only have to self-regulate their

cognitive activities, but may also have to self-regulate

their emotional and motivational states. Overall, there is

empirical evidence that young learners are not able to

use multimedia or presentation programs which give

them the opportunity to control the type, sequence,

length, and amount of information (Young, 1996).

Benefits of classroom-based PowerPoint video

presentations

Parette, Blum, Boeckmann & Watts (2009) suggested that

regardless of such concerns and problems related to the

use of PowerPoint with young learners, it is no longer an

issue of whether to use PowerPoint or not. Instead,

teachers must focus on how they can best use it inside

and outside the classroom (Parette, Blum, Boeckmann &

Watts, 2009). Parette and his colleagues provided

valuable suggestions to further benefit from PowerPoint in

enhancing children's learning. They recommended that

teachers may work with families to produce and share

learning materials for home use. These materials should

be made from class slides and in an easy to use and

follow format.

RESEARCH PAPERS

22 li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

There is increasing interest in providing children with

classroom-based audio-visual materials, and video is

demonstrated to be an expanding channel for young

children learning (Sturmey, 2003). It is believed that

children who have more literacy video materials

available to them in the home will have higher language

outcomes compared to children with fewer or no

materials available (Halle, Calkins, Berry & Johnson, 2003).

The literature emphasizes the importance of considering

the potential unique possibilities that a video presents

when deciding how to support young learner

development (Cunningham & Friedman, 2009). Martin

(1990) found that watching video is considered as a basis

for mental activity, because children already have

considerable practice with it in non-school settings. In

addition, it is socially acceptable and widely used and

supported by multimedia cell phones and portable

media players, and therefore it can be a powerful link

between the classroom and home.

Moreover, Schwartz and Hartman (2007) argued that

video is a more forgiving and powerful learning medium

when it is embedded within a larger context of use. It does

not have to be stand-alone, like a television program.

Children can start, rewind, forward, and pause the video

to address their specific needs. It can be used in many

ways to encourage learning interactions and create

engagement, even though the video itself may not

contain the new information children are supposed to

learn. In addition, Close (2004) believes that children's

vocabulary could be enhanced by age-appropriate and

quality video content, including exposure to new and

familiar words, frequent exposure, possibilities for

interaction, and some adult co-viewing. Close

concluded that co-viewing with adults is not necessary for

vocabulary development when children are viewing

high-quality and age-appropriate video content and are

confronted with familiar words and their meanings.

The Professional Development in Autism Center (2006)

reviewed research carried out to investigate the

effectiveness of video lessons and concluded that there is

strong evidence for the use of video in developing a wide

variety of skills to a large number of young learners,

including social interaction behaviors, academic skills,

communication skills, and daily living skills. For example, a

study by Kinney and colleagues which examined the use

of computer video models to teach generative spelling to

children with autism revealed that viewing video models

of the teacher writing and spelling words helps children to

rapidly learn how to spell words (Kinney, Vedora & Stromer,

2003).

1. Problem of the study

Although early childhood education teachers use

multimedia presentations inside their classrooms to

engage children and enhance their literacy skills, children

who are at-risk or have lower literacy skills require more

home intervention to acquire emergent literacy skills using

more supportive and individualized multimedia content.

However, despite the fact that technology has put digital

video equipment and applications in the hands of

teachers, producing classroom-based video materials

for home intervention requires more skill and know-how

than just having the right equipment (Longman & Hughes,

2006). Therefore, the need was emphasized to assist

teachers to produce and supplement their children with

quality classroom-based video content. This video should

be effective in improving children's emergent literacy skills

and appropriate for their needs and desires.

2. Research questions

This study seeks to answer the following two questions:

·Do supplementar y classroom-based video

presentations support children's emergent literacy

development?

·How are children's reactions toward video

presentations produced by their teachers?

3. Purpose of the Study

The main purpose of this study was to examine the

effectiveness of video presentations prepared by the

classroom teachers in supporting early literacy

development in childhood education. Therefore, the

need was emphasized to assist teachers to produce, use,

and assess the effectiveness of their classroom-based

video presentations. To achieve this purpose, a

presentation recording system for early childhood

RESEARCH PAPERS

23li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

classrooms was developed. This system accommodates

the requirements of producing video materials for young

learners, and allows the children to re-experience the

content they learned in the classroom.

4. Significance of the study

Producing and supplementing video content for young

children to access outside the classroom has received

considerable endorsement from parents and early

childhood educators. Developing and evaluating

classroom-based video presentations allows children the

ability to review class material at their own pace at home,

in surroundings in which they are comfortable, as many

times as required and in the format that suits their interests.

In addition, another group of children who are thought to

derive learning support from the availability of video

recordings are those with disabilities or medical

conditions. This study sought to gain a better

understanding of the development, use, and evaluation

of classroom-based video presentations from both a

practical and pedagogical perspective.

5. Methodology

5.1. Participants

The participants were teachers and children in a full-day

kindergarten in the Sultanate of Oman, with 52 children (4-

6 years) enrolled. There were three classrooms in the

kindergarten with 15–18 students per class. The teachers

were all female and had an average of 4 years of

teaching experience. The kindergarten curriculum

focused intensively on early Arabic and English reading

skills, such as concepts of print, phonemic awareness,

alphabetic principle, comprehension, and the

interpretation of text. Literacy instruction occurred for

approximately two hours per day. Classroom lessons

included instructional materials and activities that

covered alphabetic instruction, phonological awareness

activities, and word reading. Each lesson included at least

one alphabetic activity and one phonological awareness

activity.

5.2. The Solution

5.2.1. Motivation

The review of the literature and existing classroom

technologies revealed that choosing an appropriate

system for producing video presentations is not easy.

There is a wide range of what is known as "conversion",

"presentation recording", or "lesson capture" technologies

available and used today. These technologies range from

very simple converter software (convert PowerPoint

presentation to standard video or Flash video) to highly

sophisticated capture stations with multiple cameras and

dedicated computers. The majority of these solutions are

sophisticated applications designed for university settings

and intended for large‐scale distribution. None of these

solutions (e.g., Camtasia Studio, authorPoint, Wimba, etc.)

has been developed specifically with early childhood

teachers' and children's needs in mind.

Therefore, early childhood teachers will not be able to

integrate any of these technologies into their classroom

practices. Wilson (2010) agreed that "even when a basic

level of sophistication has been decided on, there are

many offerings with very similar feature sets that make

choosing one somewhat difficult" (p.1). This situation has

placed an emphasis on the need to develop a simple but

usable solution specifically for producing effective video

materials for young children. The solution should leverage

existing technology that can be directly administered by

teachers without the need of significant support services

and accommodate the technical differences among

teachers along with the pedagogical and psychological

principles of multimedia design for young children.

5.2.2. Assumptions and principles of design

The general design principles of the system are derived

from the authors' experiences and grounded in results

from the literature in early childhood education,

multimedia learning, and software design. In addition,

many existing solutions, as mentioned above, are

reviewed and analyzed to learn from their characteristics

in the design of the proposed solution. The review

revealed many important principles, guidelines, and

features for consideration in designing the proposed

solution. Examples of these findings are below.

The first finding from this body of research is that

overcoming the limits of a childs working memory

RESEARCH PAPERS

24 li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

(cognitive load theory) requires presenting part of the

information being taught in a visual mode and part of it in

a verbal mode (Homer, Plass, & Blake, 2008; Mayer, 2001).

Presenting lesson information in both visual and verbal

formats helps children to construct their own knowledge

and retrieve information more easily in the future. Mayer

(2001) provided a practical set of research-based

principles that can help reduce cognitive load in

PowerPoint-based video materials. These principles are

the Signaling Principle, the Segmenting Principle, the

Modality Principle, the Multimedia Principle, and the

Coherence Principle. For example, Mayer argued that

learners understand a multimedia explanation better

when the words are presented as narration rather than on-

screen text (the Modality Principle). These guidelines and

principles were considered in the design of the video

presentation.

A second finding emphasized the concept of video

presence and personalized narration within multimedia

environments. Research indicated that although

displaying the video of the teacher along with the slides

creates a visual distraction, taking children's attention

away from the visual information in the slides, the

presence of the in teacher view is important to give

children a sense of interacting with the teacher (sense of

social presence) while watching the video lesson and

may improve learning outcomes for children, even

though it adds to the cognitive load (Homer, Plass, & Blake,

2008; Mayer & Moreno, 1998). Gunawardena (1995)

found that social presence is necessary to improve,

support, and personalize children in technology-based

learning environments. Therefore, the video of the

teacher, along with the visual presentation of slides were

combined together in the video presentation layout.

A third finding highlighted many issues related to the

technical design of video production solutions. Zhu &

Bergom (2010) indicated that the skill level required to

produce videos and make them available should be fairly

minimal without the need for significant support services.

In addition, the solution should make videos available as

soon as possible after a class without further manipulation

or editing before they are available for viewing, since

most children need to watch the video for a few hours of a

given lesson (Wilson 2010). Copley (2007) and Dey, Burn &

Gerdes (2009) emphasized that the system must

combine audio, video (via digital camera or webcam),

and slides simultaneously into a single video frame

(Copley, 2007; Dey, Burn & Gerdes, 2009). Overall, the

solution should combine PowerPoint slides, freehand

drawing and typing, and the teacher's audio and video

into a single video frame that children can view outside of

class. The output should be produced in a standard and

high-quality output format capable of running on any

computer, mobile device, or standard home DVD player.

With the above principles and requirements in mind, the

authors have carefully designed the architecture of the

system. Consequently, the main intention of the

development phase was to find and build the

appropriate recording technique that acquires and

synchronizes the PowerPoint slides and teacher's video

presence simultaneously. The primary output of this phase

was a complete code, a fully functional beta version of

the entire software (called RealShow). To determine

whether the prototype met the needs and expectations of

teachers, and in order to collect user-performance and

satisfaction data, a series of tryouts were conducted using

one-to-one and small groups of teachers (5) at different

local kindergartens. The computer experience of the

volunteers varied. During tryouts, the researcher collected

and recorded the problems, comments, and suggestions

of the teachers.

5.2.3. Description of the solution

The software obtains media content from a variety of

resources and devices, including webcam, microphone,

PowerPoint slides, drawing board, and typing board in a

simplified manner. The technique involves opening

regular PowerPoint slides in a window and capturing the

presentation in real time while the teacher describes and

explains the content. This window shows and manipulates

the presentation the same way as if it was opened and

treated in the full-screen mode. The teacher can navigate

forward and back through slides, and employ other

features, including slide transitions, text and graphic

animation, slide timing, mouse movement, audio effects,

RESEARCH PAPERS

25li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

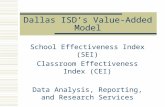

embedded video, and pen annotation (Figure 1).

The same window is used as a camera viewer to show the

teacher's view using a digital camera or laptop built-in

webcam and microphone. More than one camera might

be connected to give views of other objects or toys. The

teacher can generate professional-looking videos by

switching between multiple camera views, which is

important for creating attractive video materials. A

window, which works as a whiteboard, was integrated to

help teachers write and draw using a graphic tablet and

digital pen with a USB interface instead of a mouse. This

window allows the teacher to toggle between slides,

whiteboard, and different webcams while recording,

which simplifies the capture process. Figure 1 shows the

architecture diagram of the system when capturing a

lesson. Recording the presentation captures what the

teacher is displaying in the window synchronously. As soon

as the teacher loads the presentation into the window, she

can start the recording process with a single click of a

button, allowing her to immediately share the record with

children and parents (Figure 2).

5.3. Evaluation instruments

5.3.1. Teacher Rating of Oral Language and Literacy

(TROLL) scale

In this study, the need was emphasized to use an

instrument to identify children who are most in need of rich

language and literacy support in order to catch up to their

peers in this regard. The same instrument would be

implemented to detect changes that occurred as a result

of the intervention effort and keep track of children's

literacy growth. This instrument should rely on a teacher's

professional judgment of a child's development. In

addition, it should allow teachers to track a childs interests

in various English and Arabic language and literacy

activities, which is difficult to capture using direct

assessment tools.

The review of the literature revealed that the Teacher

Rating of Oral Language and Literacy (TROLL) is one of the

optimal tools in this regard. TROLL is a rating scale

developed by Dickinson (1997). TROLL was developed to

provide teachers with a way to measure the literacy skills

and development of children in early childhood

classrooms. No training is required for using TROLL. It is

designed so that classroom teachers can easily track the

language and literacy development of their students.

Based on the results of the instrument field testing, it

requires 5–10 minutes for each child and, with a little

planning, can be completed without disrupting

classroom activities. Skills assessed include language,

reading, and writing abilities.

TROLL covers many of the early reading and writing skills. It

contains three subscales: (i) language use, (ii) reading,

and (iii) writing. Introductory questions determine the

language the child speaks and his or her comprehension

and production abilities. The tool has 25 items, each

measured on a scale that varies slightly by item. Total

RESEARCH PAPERS

26 li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

Figure 1. Media capture and acquisition technique in RealShow

Figure 2. The main user interface of RealShow with PowerPoint presentation

scores are calculated simply by adding individual scores

on these 25 scales; total scores vary from a minimum of

24 to a maximum of 98. These total scores provide

teachers with both an indication of an individual child's

development relative to other children and a means to

chart an individual child's growth.

The psychometric properties of the instrument were

examined at the Center for the Improvement of Early

Reading Achievement, University of Michigan, by

Dickinson, McCabe & Sprague (2001). The instrument was

found reliable and has strong internal consistency. The

alphas for separate language, reading, and writing

subscales by age ranged from .77 to .92, representing

strong internal consistency. Its validity has been

established in numerous ways; TROLL correlates

significantly with scores on the Peabody Picture

Vocabulary Test and the Early Phonemic Awareness Profile

given to the same children by trained researchers.

To make TROLL available to the intended Arabic-speaking

teachers, the instrument was translated into Arabic by a

bilingual university instructor and then independently re-

translated back into English by a second bilingual

instructor to confirm the accuracy of the translation.

5.3.2. Parents' interview

To understand children's reactions to the use of classroom

video presentations and parents' perception of the

importance of videos to their young children, telephone

interviews were carried out with parents during and at the

end of the implementation, since children are regarded

as being limited informants. The main intention if

interviewing parents during the implementation was to

increase their awareness, observation, and interaction

with children. Although many parents did not like to be

involved, interviews led to more parental investment in the

process and provided valuable information, particularly

with those who had the ability to supervise their children.

The interviews with parents addressed the following

questions related to children's home use of classroom

video presentations.

1. How many videos does your child watch each week?

2. How many times does he/she watch each video?

3. Does he/she talk about video presentations to you?

4. What is the overall reaction of your child towards the

videos?

5. To what extent does he/she like the videos?

6. To what extent is he/she stimulated by the videos?

7. Does he/she find the videos easy to understand?

8. Do you believe that the videos are useful?

9. Do you find the videos supportive?

10. Do you believe that the videos improve your child's

overall learning?

11. What kinds of skills do you think he/she learns from

videos, if anything?

5.4. Procedure and Implementation

The kindergarten administration was contacted and was

supportive of the study, and provided access to the

teachers and children. Firstly, teachers were interviewed

to gain information on their educational philosophy,

computer experiences, and beliefs in relation to

computer use in early childhood education. In addition,

teachers were trained for one week to produce effective

PowerPoint presentations, using MS PowerPoint 2003/2007,

or to modify their own slides for the purpose of promoting

children's oral language and literacy skills. Person-level

orientation and group workshops were found to be

appropriate approaches to train teachers on how to use

RealShow and prepare 10-minute video presentations.

Based on research on multimedia (Mayer, 2001; Close,

2004), teachers were advised to prepare and record

PowerPoint presentations that include the following:

minimal visual or auditory stimuli, a balance between new

and familiar words, interesting material for adults to

encourage co-viewing, use of some sophisticated

language, content that offers possibilities for interaction

and participation through songs and questions, simple

narratives, language-rich content, and the age-

appropriateness of the presentation (Figure 3).

In addition, the use of supplementary video materials was

based on what is known as “home literacy programs”,

which focus on parent-child interaction and co-viewing

as a means of enhancing the literacy and language

RESEARCH PAPERS

27li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

development of the child. These kinds of programs

assume that the same techniques used in classroom-

based settings would be as successful in home-based

settings and generally have positive results for participants

(Saint-Laurent & Giasson, 2005). A variety of techniques

can be successful at promoting children's literacy skills;

these include engaging in book reading and providing

parents with literacy development materials, which have

been proven to have long-lasting effects on children's

cognitive and literacy skills (Halle, Calkins, Berry & Johnson,

2003).

In this study, parents were contacted by phone and

advised to encourage their children to view the videos at

home, and that co-viewing the videos with parents is

necessary for the purpose of the study. These videos were

coupled with further video-based activity sheets that

systematically encouraged children to apply what they

are viewing or just viewed in the video. Activities required

children, for example, to listen to words spoken aloud by

the teacher while looking at letters and pictures

representing those words and making judgments about

whether they had a common onset or rhyme. Other word

activities required children to combine and recombine

onsets and rhymes to make real words.

RealShow was installed on teachers' portable computers.

These computers were equipped with built-in webcams

and graphic tablets for hand drawing and writing.

Secondly, prior to the implementation, the teachers of the

two classes (n=52) were asked to rate their children's

native language competence. Total scores were

calculated simply by adding individual scores on the 25

items. These total scores provided the teachers with both

an indication of an individual child's level relative to other

children, along with a means to chart an individual child's

level. Table 1 displays what different scores on TROLL

indicate about a child's overall level.

For example, a score of 47 indicates that the child is

making progress that is average for four-year-olds. A TROLL

total score that corresponds to particular percentiles was

computed by converting the raw scores of the total

sample to percentiles. Therefore, children who scored 38

and below (n=12) were considered as they need extra

involvement in literacy activities. Only those children

(treatment group) were provided with video presentations

for further involvement and home use.

The teachers and children of the treatment group were

monitored for 16 weeks (Spring 2011) to guide the

teachers and researchers to ascertain data in relation to

children learning and their reactions to video

presentations. Classes were taught by the same teachers

using the same curriculum. The teachers reported

following the same daily routine for their two classes. The

only difference was that treatment group children

rece i ved reco rded Powe rPo in t -based v ideo

presentations prepared by the teacher, allowing them to

spend extra time engaged in language‐related

demonstrations. This type of design eliminates many

potential threats to internal validity related to teacher and

group variables which are often seen in field studies

assessing the effectiveness of supplementary materials

(Troia, 1999).

RESEARCH PAPERS

28 li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

Figure 3. Sample video presentation produced by the teacher

Relative standing

on the TROLL

TROLL

scores

Recommendations/Meaning

10 th percentile 29 Child is scoring very poorly relative to his/her peers. Discuss concerns with parents.

25th percentile 38 Extra involvement in extended conversations

and other literacy activities.

50th percentile 47 Child is performing at an average level.

75th percentile 59 Child is performing above average.

90th percentile 63 Child should be encouraged to read and write at advanced levels in school and at home.

Table 1. Teacher ratings of children on TROLL and its meaning

RESEARCH PAPERS

29li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

6. Results

6.1. TROLL

Examination of pre-test mean scores revealed that there

were significant differences between the children at-risk

(treatment group) and the remaining children (control

group) in the three TROLL sub-scales and the TROLL total

score (Table 2). Children at-risk had a mean score of

36.80 (SD = 2.31), a score that falls at or below the 25th

percentile. The remaining children (not at-risk) received a

mean score of 46.32 (SD = 4.38). The T-test revealed a

significant difference between the scores of the children

of the two groups in the total score and the language use,

reading, and writing sub-scales.

Teachers administered the TROLL four months later at the

end of the year to 57 children aged 3-5 years. All children

(n=52) were rated by their teachers using TROLL to

compare the literacy development of the treatment

group children (n=12) to their control group classmates

(40). The post-median scores of the treatment and control

groups indicated that, overall, there were significant

differences still between the two groups in the total TROLL

score, indicating that no improvement had occurred in

the oral language and literacy of the treatment group

children compared to the control group children.

Further examination of the mean differences in the three

sub-scales revealed that the post-median for the

treatment group in the language use subscale was

improved to 11.65 and there was no significant difference

between the two groups (p>0.05), indicating that the

children of the treatment group were beginning to be

involved with video presentations and start conversations,

communicate their experiences, and asking questions.

However, significant differences were noticed in the other

two sub-scales. The mean scores were significantly lower

for the treatment group than the control group, indicating

that no improvement was made in the treatment group

children's reading and writing abilities. Table 3 presents the

post-test language use, reading, writing, and total mean

scores on TROLL for the children in the treatment and

control groups.

6.2. Parents' interview

In order to understand the impact of pre-recorded video

presentations on young children's literacy development,

eight (father or mother) out of twelve families of the

treatment group children were interviewed. Data were

collected through open ended interviews which were

conducted to obtain information about the children's

reactions toward the videos and the families' perceptions

of their children's acquisition of early literacy skills. The

researchers helped family members by asking about

specific experiences, such as the number of videos the

child watches each week, number of times the child

watches each video, reaction of the child towards the

videos, the extent to which the child likes the videos, and

whether parents believe that the videos improve the

child's literacy or not. The responses to the interview

questions are organized, analyzed, and coded to

address the second research question. However, since

many responses contained multiple beliefs, the number

of codes assigned to each passage varied. Responses

are categorized into three groups: frequency of watching

the videos (questions 1 & 2), reactions toward the videos

(questions 3, 4, 5, 6 & 7), and usefulness of video

presentations (questions 8, 9, 10 & 11), and according to

the type of feedback (general or distinctive), as shown in Scale/Sub-scale Treatment

Group (n=12) Control Group (n=40)

Mean

difference

t

Mean SD Mean SD

Language use(out of 24)

8.91

1.3789

11.25

1.9578

2.34

3.84*

Reading (out of 32)

12.25 1.0552 15.45 1.5843 3.20 6.55*

Writing (out of 42)

14.91

0.7929

19.62

2.6572

4.70

6.02*

Total (out of 98)

36.8 2.3143 46.32 4.3875 10.24 7.73*

Table 2. Pre-test mean scores of treatment and controls groups in TROLL

Scale/Sub-scale Treatment Group (n=12)

Control Group (n=40)

Mean

difference

t

Mean SD Mean SD

Language use (out of 24)

11.65 1.8257 11.66 1.9942 .0166 .026

Reading (out of 32) 12.91 1.2401 15.82 1.5994 2.9083 5.784*

Writing (out of 42) 15.16 0.9374 20.00 2.7174 4.8333 6.018*

Total (out of 98) 39.75 2.4908 47.47 4.5741 7.7250 5.581*

Table 3. Post-test mean scores of treatment and controls groups in TROLL

RESEARCH PAPERS

Table 4.

Overall, feedback from interviewees showed that children

liked to watch video presentations prepared by their

teachers every day and more than one time for each

video. In addition, they found videos interesting enough to

talk about with their parents. Responses from parents also

indicated that children felt the video presence of the

teacher attractive and simulating. Parents believe that

video presentations were useful and affected their

children's language development and curiosity positively.

In addition, parents highlighted many viewpoints related

to their own perception toward the usefulness of videos to

their children, along with their children's reactions toward

the videos. One parent addressed that “my child was able

to benefit from watching the video lessons better than

other video movies seen on the TV”. In addition, two

parents noticed that videos increased their children's

vocabularies. One parent indicated that “I think that

videos have really helped to increase my child's

vocabulary”. Another parent added that “These videos

are helpful if my child views the video with me to interact

with him while the video is running”.

At the same time, many concerns were highlighted by

parents regarding the time spent in watching video

presentations in front of the computer or TV screen

compared to other types of activities. A parent argued

that “My child can watch these video shows for a long time

but he seems to have trouble paying attention to other

activities like reading or speaking with me”. Another parent

argued that the number of video presentations her child

should watch every week is too much. She argued that “it

was better if the teacher could provide the child with one

video presentation at the end of each week to revise the

lessons he learned”. In terms children's reactions toward

the videos, one parent commented that although her

child liked to view video materials prepared by his own

teacher, she did not like her child to look at the TV or

computer screen most of the time.

7. Discussion, Implication & Conclusion

Although very little has been published in the literature

about the use of supplementary video lessons prepared

by the teacher in early childhood education, findings

from this preliminary study point to its effectiveness. This

study examined the effectiveness of a new approach of

video presentations prepared by the class teacher to

supplement children who had low early literacy and

language skills on children with emergent literacy

development. The aim of these video presentations was

to support young learner 's emergent l i teracy

development and develop their knowledge of letters and

sounds, along with knowledge of narrative and

storytelling. These videos were prepared using a tool

30 li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

Results General patterns (frequency) Distinctive viewpoints (frequency)

1. Frequency of watching the videos

1. Child watched videos 3-4 times a week (8).

2. Child liked to watch each video times a week (8).

presentation 1-2

1. These videos increased my child’s use of the TV screen (1).

2. Too much watching time can interfere with physical activities (1).

3. My child is too young to watch all these videos (1).

2. Reactions toward the videos

1. Child liked to talk about video parents (3).

presentations with

2. Child has a positive reaction towards the videos (3).

3. Child liked to watch the videos (4).

4. Child was attracted by the videos (5).

5. Child found the videos easy to understand (5).

1. My child liked to watch the same video repeatedly (2).

presentation

2. My child was reciting bits of dialogue or while viewing (1).

singing the songs

3. My child liked the content and construction of the show (2).

4. I do not like my child to look directly at the television screen (1).

3. Usefulness of video 1. The presentation videos are useful to my child (8).

2. The videos support my child’s literacy development (7).

3. The videos improve my child’s overall learning (8).

4. My child was taught how to listen and the video (3).

read from

5. My child learned how to talk about in the class (4).

what he/she learned

1. My child understood the video content other videos (1).

better than

2. These videos increased my child’s vocabularies (2).

3. The video was more beneficial when it with me (2).

my child viewed

Table 4. Analysis of interview results (n=8)

called RealShow, developed by the authors specifically

for the purpose of this study. The kindergarten classes

available for this study provided an opportunity to

investigate the effectiveness of video presentations in

closely matched treatment and control settings.

Comparisons were made between the treatment group,

who received the supplemental video presentations, and

a control group, without further support. Two groups were

used to provide assurances that group differences were

due to the use of teachers' video presentations with the

treatment group children, and not down to other

potentially confounding variables. The differences

between the treatment group and the control group on

the post-test total score indicated that the treatment

group children did not benefit from the supplementary

video presentations. However, a closer look at the mean

scores of the language use subscale revealed that the

treatment group children's language use was

encouraged by the quality content offered by the videos.

Better scores for the treatment group on the language use

sub-scale indicated that viewing supplementary video

presentations prepared by the teacher encouraged

children to ask questions about topics that interest them,

begin conversation with either parents or the teacher, tell

parents about events that happened in the classroom, or

recognize and produce rhymes. In emergent literacy

instruction, the results of this study indicate that producing

video presentations using RealShow holds promise for the

development and enhancement of emergent literacy

skills.

This result suggests that when children were exposed to

video content at home, they might benefit from parent

co-viewing. Interviewees confirmed that co-viewing the

videos with their children promoted their talk and made

verbal responses more frequent. The literature also

indicates that co-viewing of informative videos with

children is encouraging and useful to children. It was

found to enhance children's ability to ask questions and

talk with adults, which contributed significantly to

children's level in language use (Roberts and Howard,

2004). These findings are consistent with the extant

literature describing the importance of using multimedia

presentations in early literacy development (Parette,

Blum, and Watts, 2009; Parette, Quesenberry, and Blum,

2010).

Although young children who are at-risk may require

intervention to acquire emergent literacy skills, the

findings indicate that learning from supplementary video

presentations may be beneficial not only for children who

are struggling, but also for typically developing children.

Therefore, it is essential to continue examinations into how

it can be used as an effective tool for emergent literacy

development. For example, video presentations could be

produced by teachers to target specific emergent

literacy skills, or utilized to individualize learning and

engage children using strategies, such as questions and

songs. This use can support a wide range of literacy skills in

early childhood education, such as vocabulary

development, comprehension, and phonological

awareness skills in young children (Zucker, Moody, and

McKenna, 2009).

Overall, the findings are very encouraging and warrant

additional research aimed at determining the potential

contr ibut ion that the classroom-based v ideo

presentations may have on early literacy skills in young

children. Although the study had several limitations that

must be considered in light of the results, including the

lack of an adequate number of children in the treatment

group and possible interpretation problems resulting from

home-based treatment, instructional decisions about

producing and supplementing young children with video

presentations must be made on the face validity of the

technology (Parette et al., 2009).

While having a video can provide children with the

experience of viewing their teacher present material, this

can become a static pedagogical method. The

challenge for teachers is to push the tool to its limits,

providing more than a static form of video information to

children and creating interactive videos through which

children will be engaged and challenged to learn.

Therefore, teachers should consider the interactive

possibilities that a PowerPoint video lesson presents when

deciding how to package, deliver, and present video

presentations to children (Osborn, 2010).

RESEARCH PAPERS

31li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

Since successful technology integration is dependent on

the teachers' acceptance and knowledge of technology,

training teachers to produce and supplement children

with remedial video materials should be encouraged to

make them feel comfortable with the use of technology

and to further investigate the long-term effects of video

presentations on children's expressive language. In

addition, further investigations are needed to observe

children's use of video presentations at home, and

encourage the use of interactive video features in literacy

development.

References

[1]. Boekaerts, M. (1995). Self-regulated learning: Bridging

the gap between metacognitive and metamotivation

theories. Educational Psychologist, 30(4), 195-200.

[2]. Chiasson, S., Gutwin, C. (2005). Design Principles for

Children's Software., Technical Report HCI-TR-05-02,

Computer Science Department, Univers i ty of

Saskatchewan.

[3]. Close, R. (2004). Television and language

development in the early years: a review of the literature.

National Literacy Trust, London.

[4]. Cunningham, A. & Friedman, A. (2009). Captivating

Young Learners and Preparing 21st Century Social Studies

Teachers: Increasing Engagement with Digital Video. In I.

Gibson et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of Society for Information

Technology & Teacher Education International

Conference 2009 (pp. 1797-1803). Chesapeake, VA:

AACE.

[5]. Dickinson, D., McCabe, A. & Sprague, K. (2001).

Teacher Rating of Oral Language and Literacy (TROLL): A

Research-Based Tool. A research-based tool. Center for

the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement,

University of Michigan.

[6]. Dickinson, D. (1997). Teacher Rating of Oral

Language and Literacy. Center for Children & Families,

Education Development Center.

[7]. Grabe, M., & Grabe, C. (2007). Integrating

technology for meaningful learning (5th ed.). New York:

Houghton Mifflin.

[8]. Gunawardena, C. (1995). Social presence theory

and implications for interaction and collaborative

learning in computer conferences. International Journal

of Educational Telecommunications, 1(2), 147–166.

[9]. Gunn, B. G., Simmons, D. C., & Kameenui, E. J. (2000).

Emergent literacy: Synthesis of the research.

[10]. Halle, T., Calkins, J., Berry, D. & Johnson, R. (2003).

Promoting language and literacy in early childhood care

and education settings. Child Care and Early Education

Research Connections (CCEERC). Columbia University,

New York.

[11]. Homer, B., Plass, J., & Blake, L. (2008). The effects of

video on cognitive load and social presence in

multimedia-learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 24

(3), 786–797.

[12]. Invernizzi, M., Landrum, T., Teichman, A., &

Townsend, M. (2010). Increased Implementation of

Emergent Literacy Screening in Pre-Kindergarten. Early

Childhood Education Journal, 37(6), 437–446.

[13]. Kinney, M., Vedora, J. & Stromer, R. (2003).

Computer-presented video models to teach generative

spelling to a child with an autism specturm disorder.

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 5(1), 22-29.

[14]. Loisel, M. & Galer, R. (2004). Uses of PowerPoint in the

314L Class. Computer Writing and Research Lab, White

Paper Series: #040505-3.

[15]. Longman, D. & Hughes, M. (2006). Whole Class

Teaching Strategies and Interactive Technology: towards

a connectionist class. Paper presented at the British

Educational Research Association Annual Conference,

University of Warwick, 6-9 September.

[16]. Martin L. (1990). Detecting and defining science

problems: A study of video-mediated lessons. In Moll, L.

(Ed.), Vygotsky and education: Instructional implications

and applications of sociohistorical psychology,

Cambridge (pp 372–402): Cambridge University Press,

MA,.

[17]. Mayer, R. (2001). Multimedia-learning. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

[18]. Mayer, R. & Moreno, R. (1998). A split-attention effect

in multimedia-learning: evidence for dual processing

RESEARCH PAPERS

32 li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

systems in working memory. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 90(2), 312–320.

[19]. Mills, C. & Roblyer, D. (2006). Technology tools for

teachers. A Microsoft Office tutorial (2nd ed.). Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Merrill Prentice Hall.

[20]. Moody, A. (2010). Using Electronic Books in the

Classroom to Enhance Emergent Literacy Skills in Young

Children. Journal of Literacy and Technology. 11(4), 22-

52.

[21]. National Association for the Education of Young

Children (1996). Technology and Young Children—Ages

3 through 8. A position statement of the National

Association for the Education of Young Children,

Washington, DC: NAEYC.

[22]. Osborn, D. S. (2010). Using video lectures to teach a

graduate career development course. Retrieved from

http://counselingoutfitters.com/vistas/vistas10/Article_35.

[23]. Parette, P., Wojcik, W., Stoner, B. & Watts, H. (2007).

Emergent writing literacy outcomes in preschool settings

using AT toolkits. Presentation to the Assistive Technology

Industry Association (ATIA) Annual Meeting, Orlando, FL.

[24]. Parette, P., Hourcade, J., Boeckmann, N. & Blum, C.

(2008). Using Microsoft PowerPoint to Support Emergent

Literacy Skill Development for Young Children At-Risk or

Who Have Disabilities. Early Childhood Education Journal,

36(3), 233–239.

[25]. Parette, P. Hourcade, j. Dinelli, M. and Boeckmann,

M. (2009). Using Clicker 5 to Enhance Emergent Literacy in

Young Learners. Early Childhood Education Journal, 36(4),

355-363.

[26]. Parette, P., Blum, C., Boeckmann, N. & Watts, H.

(2009). Teaching Word Recognition to Young Children

Who Are at Risk Using Microsoft PowerPoint Coupled With

Direct Instruction. Early Childhood Education Journal,

36(5), 393–401.

[27]. Parette, P., Blum, C. & Watts, H. (2009). Use of

Microsoft PowerPoint and direct instruction to support

emergent literacy skill development among young at risk

children. In Vilas, A., Martin, A., Gonzalez, J. & Gonzalez, J.

(Eds.), Research, reflections and innovations in

integrating ICT in education (Vol. 2; pp. 864-868).

Badajoz, Spain: FORMATEX.

[28]. Parette, P., Quesenberry, C., & Blum, C. (2010).

Missing the boat with technology usage in early childhood

settings: A 21st century view of developmentally

appropriate practice. Early Childhood Education

Journal, 37(5), 335–343.

[29]. Professional Development in Autism Center (2006).

Video Modeling. University of Washington, Research Brief

#2, Retrieved from http://depts.washington.edu/pdacent

[30]. Roberts, Susan and Howard, Sue (2004). Watching

Teletubbies: television and its very young audience, in

Marsh, J. (ed.) Popular Culture, Media and Digital

Literacies in Early Childhood, London: Routledge Falmer.

[31]. Saint-Laurent, L., & Giasson, J. (2005). Effects of a

family literacy program adapting parental intervention to

first graders' evolution of reading and writing abilities.

Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 5(3), 253-278

[32]. Schwartz, L., & Hartman, K. (2007). It is not television

anymore: Designing digital video for learning and

assessment. In R. Goldman, R. Pea, B. Barron, & S. J. Derry

(Eds.), Video research in the learning sciences (pp. 349-

366). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

[33]. Sturmey, P. (2003). Video Technology and Persons

with Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. Journal

of Positive Behavior Interventions, 5(1), 3-4.

[34]. Troia, G. (1999). Phonological awareness

intervention research: A critical review of the experimental

methodology. Reading Research Quarterly, 34(1), 28-52.

[35]. Whitehurst, J., & Lonigan, J. (2002). Emergent

literacy: Development from prereaders to readers. In S. B.

Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook of early

literacy research (pp. 11-29). New York: The Guilford Press.

[36]. Wilson, M. (2010). Lecture Capture Overview.

ComETS 2010 Symposium, Iowa State Memorial Union,

February 18.

[37]. Young, D. (1996). The effect of self-regulated

learning strategies on performance in learner controlled

computer-based instruction. Educational Technology

Research and Development, 44(2), 17-27.

RESEARCH PAPERS

33li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

[38]. Zimmerman, J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and

academic achievement: an overview. Educational

Psychologist, 25(1), 3-17.

[39]. Zimmerman, J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated

learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64-72.

[40]. Zucker, T., Moody, A., & McKenna, M. (2009). The

Effects of Electronic Books on Pre-Kindergarten-to-Grade

5 Students' Literacy and Language Outcomes: A

Research Synthesis. Journal of Educational Computing

Research, 40(1), 47-87.

[41]. Zue, E. and Bergom, I. (2010). Lecture Capture: A

guide for Effective Use. Occasional Papers, No. 27, Center

for Research on Learning and Teaching, University of

Michigan.

RESEARCH PAPERS

34 li-manager’s Journal o Psychology, Vol. No. 3 ln Educational 5 November 2011 - January 2012

Alaa M. Sadik works as an Associate Professor of instructional technology at South Valley University, Egypt, and currently on leave (2006-present) to work at Department of Instructional & Learning Technology, College of Education, Sultan Qaboos University, Sultanate of Oman. He received his Ph.D. degree in Educational technology from the Institute for Learning, the University of Hull, United Kingdom, in 2003. He is interested in the integration of computer and Internet applications in education to improve teaching and learning particularly in developing countries.

Khadeja Badr works as an Assistant Professor of Educational Psychology, Faculty of Educational, at South Valley University, Egypt. She received her Ph.D. degree from South Valley University in learning disabilities at pre-school education. She is interested in the preparation of pre-school children for reading and writing, and visual and auditory procession disorders.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS