The ECG role in identifying the etiology of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy (TIC) ·...

Transcript of The ECG role in identifying the etiology of tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy (TIC) ·...

P.O. Box 2925 Riyadh – 11461KSATel: +966 1 2520088 ext 40151Fax: +966 1 2520718Email: [email protected]: www.sha.org.sa

CA

SE R

EPO

RT

Received 25 May 2011; revised 15 October 2011; accepted 23 October 2011.Available online 10 December 2011

⇑ Corresponding author. Tel.: +966 14777714x8765; fax: +966 14778771.E-mail addresses: [email protected] (M. Al Mehairi), [email protected] (S.A. Al Ghamdi), [email protected] (K. Dagriri),

[email protected] (A. Al Fagih).The ECG role in identifying the etiology oftachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy (TIC)

M. Al Mehairi a,⇑, S.A. Al Ghamdi b, K. Dagriri c, A. Al Fagih d

a–d Department of Adult Cardiology, Prince Sultan Cardiac Centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy (TIC) is a well recognized entity of heart failure (HF) and various mechanismsdue to tachyarrhythmias have been postulated to be responsible for impaired cardiac contractility. Previously reportedcases showed reversibility of such disorders whenever stable cardiac rhythm is maintained adequately and we reporton a 16-year-old boy who has been diagnosed to have TIC, which was misinterpreted initially as sinus tachycardiasecondary to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. A complete recovery of his left ventricular function wasachieved by radiofrequency catheter ablation and highlights the importance of a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG)assessment in such patients.

� 2011 King Saud University. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: ECG, Atrial tachycardia, Cardiomyopathy, Ablation

Case

A 16-year-old boy, with a six-month history ofcongestive heart failure, was referred from

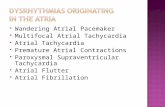

another hospital for medical management andpossible device implantation. On presentation toour hospital he was quite symptomatic and hada significant history of shortness of breath (SOB)at rest, orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnaldyspnea (PND). He had no evident history ofany preceding viral infection, drugs or alcoholaddiction that could be elicited. An electrocardio-gram (ECG) showed non-sinus tachycardia, with arate of 160 beats/min, and an inverted P-wave wasnoted at lead I, aVL, and upright P-waves at theinferior leads, suggestive of left atrial automaticfocus (Fig. 1).

1016–7315 � 2011 King Saud University.

Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

URL: www.ksu.edu.sa

doi:10.1016/j.jsha.2011.10.008

Despite optimal medical therapy for heart fail-ure at the time of admission, his echocardiographyrevealed a severely dilated left ventricle with ejec-tion fraction of 15% and severe functional mitralregurgitation.

Based on our ECG findings which are consistentwith ectopic atrial arrhythmia and amenable forradiofrequency catheter ablation (RFCA), heunderwent an electrophysiological study (EPS).An incessant form of left atrial tachycardia wasdetected during the study and a non-contact map-ping system (NAV-X-Endocardial Solutions, Inc.(ESI), St. Paul, Minnesota) was used to identifythe focus. A left atrial geometry was created, andthorough mapping was carried out using bothlocal activation and voltage mapping in

Figure 1. Pre-Ablation twelve leads electrocardiogram showed left atrial tachycardia, rate of 160 beats/min, note the inverted P wave at lead I,aVL, and upright P-waves at inferior leads and V1.

Figure 2. Three-dimensional left atrial geometry by non-contact mapping system (NAV-X-Endocardial Solutions, Inc. (ESI), St. Paul,Minnesota) showed the atrial tachycardia focus adjacent to the left superior pulmonary vein.

CA

SE REPO

RT

134 AL MEHAIRI ET ALTHE ECG ROLE IN IDENTIFYING THE ETIOLOGY

J Saudi Heart Assoc2012;24:133–136

reference to the coronary sinus (CS) catheter(Fig. 2). The area of interest was preceding CS

catheter by 58 msec, adjacent to the left superiorpulmonary vein, and a total of 10 min and 35 s of

Figure 3. Post ablation twelve leads electrocardiogram showed sinus tachycardia rate of 120 beat/min. Note the normalization of the P-wave axis.

CA

SE R

EPO

RT

J Saudi Heart Assoc2012;24:133–136

AL MEHAIRI ET AL 135THE ECG ROLE IN IDENTIFYING THE ETIOLOGY

radiofrequency energy was applied (50 W, tem-perature of 60 �C).

A complete recovery of sinus rhythm wasachieved afterward and his heart rate immediatelyreduced to 120 beats per minute (Fig. 3). A signif-icant functional capacity and general well beingimprovement were documented during followup and, with the help of anti-failure medications;cardiac function recovery was demonstrated byserial echocardiograms within six months of fol-low up.

Discussion

Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy is a welldescribed disorder that is related to various typesof arrhythmias [1–3]. Although atrial fibrillation isthe most frequent cause of ventricular dysfunctionin the adult age group, it may also be a conse-quence rather than a cause of heart failure [4,5].Unexplained systolic dysfunction is associatedwith any form of tachyarrhythmias, especially ina normally structural heart, and should be evalu-ated carefully. Many mechanisms have been dem-onstrated in experimental animal models toelucidate the pathophysiology of TIC at the levelof myocytes. Unmatched myocardial demand aswell as stiffened coronaries secondary to in-creased sympathetic tone could result in stunningphenomena [6–8]. Down regulation of beta-1-receptors [7–14], secondary to myocardial remod-eling and depletion of energy stores [12] with

consequent mishandling of calcium metabolismcan impact the myocardial contractility [8,9,15].Oxidative stress with an imbalance between pro-oxidant and antioxidant pathways was also foundto be another co-factor in the same process of TIC[10–16]. Various changes as a consequence of theafore-mentioned mechanisms described histologi-cally are such as myocyte hyperplasia and length-ening, myocardial fibrosis, impaired coronaryreserve and apoptosis [11].

The diagnosis of tachycardia-induced cardiomy-opathy requires a high index of suspicion, as theunderlying arrhythmia may not always be appar-ent. The paroxysmal nature of the events may ob-scure immediate diagnosis of abnormalarrhythmias as a cause of dilated heart. Similarly,a right-sided atrial ectopic tachycardia in a youngpatient is commonly misinterpreted as sinustachycardia. The tendency for ectopic foci inyoung patients to cluster near atrial appendagesor pulmonary veins and crista terminals may ren-der such rhythm indistinguishable from normalsinus rhythm [17]. In addition, P-wave morphol-ogy can distort the preceding QRS complex or Twave. Several studies have been published andfocused on 12-lead analysis of P-wave morphologyto determine the origin of the tachycardia. LeadsaVL and V1 are the most useful to distinguish be-tween right and left origin [18]. Right appendagefoci produces a normal frontal plane P-wave axis,but the vector of atrial depolarization in the hori-zontal plane is directed from anterior to posterior

CA

SE REPO

RT

136 AL MEHAIRI ET ALTHE ECG ROLE IN IDENTIFYING THE ETIOLOGY

J Saudi Heart Assoc2012;24:133–136

such that the P-wave in the right chest leads ispredominantly negative. Left- sided foci in theappendage and the left pulmonary vein are usu-ally quite obvious from the frontal plane, wherethe P-wave axis can be typically in the range of+90 to +180 degree. When it originates aroundthe crista terminals or right pulmonary veins, theP-wave can be hard to distinguish from sinustachycardia and other features of the ECG mustbe examined with great care [17,18].

In our patient a firm diagnosis of left atrialtachycardia was made on the basis of a standard12-lead ECG finding, which reveals a singleabnormal P-wave axis and inappropriate heartrate for the patient’s age, which was out of propor-tion to compensatory heart failure mechanism.

Conclusion

Recent advances in mapping and ablation of fo-cal tachycardia provide a safe and successful cura-tive therapy. However, recognition of suchtachycardia is the key factor for successful man-agement. A standard 12-lead surface ECG pro-vides a simple and non-invasive method that canhelp in determining the origin of tachycardia.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest todeclare.

References

[1] Cruz FE, Cheriex EC, Smeets JL, et al. Reversibility oftachycardia induced cardiomyopathy after cure ofincessant SVT. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;16:739–44.

[2] Grimm W, Menz V, Hoffmann J, et al. Reversal oftachycardia induced Cardiomyopathy following ablationof repetitive monomorphic RV outflow tract tachycardia.Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2001;24:166–71.

[3] Chugh SS, Shen WK, Luria DM, et al. First evidence ofpremature ventricular complex induced cardiomyopathy:a potentially reversible cause of heart failure. J CardiovascElectrophysiol 2000;11:328–9.

[4] Redfield MM, Kay GN, Jenkins LS, et al. Tachycardiarelated cardiomyopathy: a common cause of ventriculardysfunction in patients with atrial fibrillation referred forAV node ablation. Mayo Clinic Proc 2000;75:790–5.

[5] Calò L, De Ruvo E, et al. Tachycardia-inducedcardiomyopathy: mechanisms of heart failure and clinicalimplications. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown)2007;8(3):138–43.

[6] Moe GW, Montgomery C, Howard RJ, et al. Leftventricular myocardial blood flow, metabolism andeffects of treatment with enalapril: Further insights intothe mechanisms of canine experimental pacing-inducedheart failure. J Lab Clin Med 1993;131:294–302.Sasayama S, Asanoi H, Ishizaka S, et al. Continousmeasurement of the pressure volume relationship inexperimental heart failure produced by rapid ventricularpacing in conscious dogs. Eur Heart J 1992;13:47–51.

[8] Spinale FG, Clayton C, Tanaka R, et al. Myocardial Na, K-ATPase in tachycardia Induced cardiomyopathy. J MolCell Cardiol 1992;24:277–89.

[9] Yonemochi H, Yasunaga S, Teshima Y, et al. Rapidelectrical stimulation of contraction reduces the densityof beta-adrenergic receptors and responsiveness ofcultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Possibleinvolvement of microtubule disassembly secondary tomechanical stress.. Circulation 2001;101:2625–38.

[10] Mihm MJ, Yu F, Carnes CA, et al. Impaired myofibrillarenergetics and oxidative injury during human atrialfibrillation. Circulation 2001;104:174–82.

[11] Jovanovic S, Grantham AJ, Tarara JE, et al. Increasednumber of cardiomyocytes in cross sections fromtachycardia induced cardiomyopathy hearts. Int J MolMed 1999;3:153–5.

[12] Kloner RA, Deboer, LWV, Darsee JR, et al. Recoveryfrom prolonged abnormalities of canine myocardiumsalvaged from ischemic necrosis by coronary reperfusion.Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1981;78:7152–63. Eur Heart J1992;13:47–58.

[13] Spinale FG, Grine RC, Temple GE, Crawford FA, Zile MR.Alterations in the myocardial Vasculature accompanytachycardia induced cardiomyopathy. Basic Res Cardiol1992;87(1):65–79.

[14] Tanaka R, Fulbright BM, Mukherjee R, Burchell SA,Crrawford FA, Zile MR, et al. The cellular basisi for theblunted response to betaadrenergic stimulation insupraventricular tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. JMol Cell Cardiol 1993;25(10):1215–33.

[15] He J, Conklin MW, Foell JD, Wolff MR, Haworth RA,Coronado R, et al. Reduction in density of transversetubules and L-type Ca(2+) channels in canine tachycardiainduced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2001;49(2):298–307.

[16] Saavedra WF, Paolocci N, St John ME, Skaf MW, StewartGC, Xie JS, et al. Imbalance between xanthine oxidase andnitric oxide synthase signaling pathways underliesmechanoenergetic uncoupling in the failing heart. CircRes 2002;90(3):297–307.

[17] Josephson M, editor. Supraventricular tachycardias. In:Clinical cardiac electrophysiology: techniques andinterpretations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: LippincottWilliams &Wilkins; 2001. p. 169–271.

[18] Lee BK, Olgin JE. Ablation of focal atrial tachycardia. In:Huang SKS, Wood MA, editors. Catheter ablation ofcardiac arrhythmias. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2006(Chapter 10).