The dormouse conservation handbookptes.org/.../2014/06/Dormouse-Conservation-Handbook.pdfThe...

Transcript of The dormouse conservation handbookptes.org/.../2014/06/Dormouse-Conservation-Handbook.pdfThe...

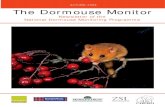

working towards Natural Englandfor people, places and nature

The dormouseconservation handbook

second edition

The dormouse conservation handbookSecond edition

byPaul Bright, Pat Morris and Tony Mitchell-Jones

Illustrated by Sarah Wroot

3The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

Foreword and acknowledgements 51 Introduction: dormice and issues they raise 9

1.1 General introduction 91.2 Organisational framework and support 10

2 Introduction to dormouse ecology 112.1 Understanding dormouse habitats and ecology 112.2 Dormice in other habitats 172.3 Problems with small population size 18

3 Finding signs of dormice and monitoring numbers 213.1 Predicting the presence of dormice 213.2 Finding evidence of dormice 213.3 Dormouse surveys – good practice recommendations 273.4 Monitoring 283.5 Marking dormice and taking samples 303.6 Estimating population density 30

4 Habitat management 314.1 Managing woods for dormice 314.2 The objectives of woodland management for dormice 314.3 ‘Conservation Woodlands’ 314.4 Coppicing for dormouse conservation 344.5 Managing ‘Forestry’ woodlands where dormice are present. 354.6 Management of Plantations on Ancient Woodland Sites (PAWS) 384.7 Managing problems caused by deer and stock browsing 404.8 Squirrels 414.9 Hedges and their management 42

4.10 Support for habitat management 43

5 Development and mitigation 455.1 Legal background and licensing 455.2 When is a licence required? 455.3 Possible impacts from development 465.4 Predicting likely impacts 465.5 Roles and responsibilities 465.6 Planning mitigation and compensation 475.7 Mitigation and compensation methods 485.8 Nest boxes 525.9 Hibernating dormice 52

6 Legislation, legal status & licensing 536.1 Relevant direct legislation 536.2 Interpretation and enforcement 536.3 Exceptions and licences 546.4 Incidental protection 546.5 Planning policy 55

Contents

4

7 Captive breeding and reintroduction to the wild 577.1 Captive breeding 577.2 Reintroductions and translocations 577.3 Progress so far 60

8 The National Dormouse Monitoring Programme 618.1 Monitoring Dormice at National and Regional Level 618.2 Other recording schemes 62

9 Conservation achievements and priorities 639.1 The UK Biodiversity Action Plan 639.2 Progress with the national action plan 639.3 Priorities for the next decade 64

10 Organisations & contacts 6510.1 English Nature 6510.2 The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 6510.3 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister 6510.4 Local Planning Authorities 6610.5 Developers and environmental consultants 6610.6 The Forestry Commission 6610.7 County Wildlife Trusts 6710.8 People’s Trust for Endangered Species and the Mammals Trust UK 6710.9 Local Biological Records Centres and the NBN 67

10.10 The Mammal Society 6810.11 Common Dormouse Captive Breeders Group (CDCBG) 6810.12 Other organisations 68

11 Case studies in development and forestry 6911.1 Developing National Cycle Route 45 in The Severn Valley, Shropshire 6911.2 Reconstructing a road junction 70

12 References 71

Nest box suppliers 73

Contentscontinued

5The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

Foreword and acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the many hundreds ofvolunteers who have helped with the study and monitoring of dormousepopulations over the past two decades. We also acknowledge thevaluable and extensive input from the Common Dormouse CaptiveBreeders Group, a number of ecological consultants, and fromrepresentatives of organisations that have been directly involved indormouse conservation, survey and mitigation work. A workshopattended by Nida Al-Fulaij, Neil Bemment, Caitriona Carlin, PaulChanin, Warren Cresswell, Fred Currie, Valerie Keeble, Roger Trout,Cathy Turtle and Michael Woods was very helpful in clarifying manyissues and identifying good practice. We are particularly grateful toRoger Trout of Forest Research for his very considerable input to thechapter on Habitat Management.

This handbook is endorsed by the Dormouse Focus Group (BAP group)as a contribution to the delivery of the Biodiversity Action Plan for thedormouse.

In October 2006, English Nature, Defra’s Rural Development Service andthe Landscape. Access and Recreation Division of the CountrysideAgency will come together to form a new agency, Natural England.Functions currently provided by RDS or English Nature, such as speciesadvice and licensing, will then be provided by the new agency.

Paul BrightPat MorrisTony Mitchell-JonesJanuary 2006

This considerably expanded second edition of the Dormouse

Conservation Handbook draws together much information on

the species that has been gathered since the first edition was

published in 1996. In particular, the introduction of a licensing

system for European protected species has highlighted the

need for guidance on mitigating the impact of development or

other operations on dormouse populations. Mitigation

studies are still developing, but we have included, wherever

possible, good practice guidance that should help determine

appropriate levels of survey and mitigation in a variety of

circumstances. Examples of successful mitigation are still

relatively rare and we would welcome further case studies as

they become available.

6

Key messages� There is only one native species of

dormouse in Britain, whose basicbiology is very different from thatof ordinary ‘mice’.

� Dormice are protected by lawbecause their numbers anddistributional range have declinedby at least half during the past 100years. This decline still continuesin some regions.

� Dormice are important becausethey are a ‘flagship species’; where dormice occur, the habitat is usually very suitable for a wide range of other species too.They are also important as‘bioindicators’ as they areparticularly sensitive to habitat and population fragmentation, so their presence is an indication of habitat integrity and sustainable populations of other sensitive species.

� Dormice normally occur in highlydiverse deciduous woodland.They are also frequently found inspecies-rich hedgerows and scruband they also occur in habitats suchas gardens and conifer plantations.

� Dormice hibernate on or under theground from about October untilMarch or April. They are thusaffected by ground disturbance inwinter and early spring.

� Dormice are vulnerable towoodland and hedgerowmanagement operations. In manyareas, deer or livestock are also amajor problem, compromisingregeneration and reducing shrublayer extent and diversity.

� The potential presence of dormiceshould be considered whendevelopment, habitat managementor land-use change is planned thataffects any type of woodland,hedgerow or scrub. A surveyshould be carried out at the earliestpossible opportunity as mitigation

measures may depend on theseason and may not be easilyaccommodated into workstimetables later. As the dormouse is a European protectedspecies, a licence may be requiredto permit activities that wouldotherwise be illegal.

� English Nature strongly advisesdevelopers to seek the services of aprofessional environmentalconsultant with appropriateexperience when contemplating adevelopment proposal that mightaffect dormice, or potentialdormouse habitat.

� When considering applications for planning permission, planningauthorities should take account ofthe presence of dormice and otherprotected species. They mayrefuse applications where adevelopment will have adverseeffects on protected fauna or flora,or if a suitable survey to assess the impact of a development onprotected species has not beencarried out. Local authoritiesshould request applicants toinstigate such a survey beforedetermination rather than adding it afterwards as a condition ofapproval.

� If disturbance to dormouse habitatcannot be avoided, mitigation toreduce or compensate for thisdisturbance is likely to be acondition of planning approval andmust be proportionate to theprobable impact of thedevelopment. Similar conditionsare likely to apply to a licence.

� Mitigation and subsequentwoodland management may haveto be carefully timed to protectdormice. Restoration of habitatcontinuity is particularly importantand should sometimes include landthat lies outside the area directlyaffected by operations. Sometimesa considerable period of time may

be necessary to carry out this work,particularly where planting isrequired that may not mature forseveral years. Arranging tomonitor the effects of mitigationand woodland management ishighly desirable, and often arequirement of planning permission

� Mitigation may involve thetranslocation of dormice, but thisshould be considered a ‘last resort’option because it is disruptive tonatural populations and suitablesites for releasing animals may notbe available locally. Moreover,establishing translocated dormicepopulations is a complex andexpensive operation that requiresspecialist supervision.

� Protected species legislationapplies independently of planningpermission. Licences may benecessary for operations that do not require planning permission but do affect dormice.

� This document gives genericadvice on woodland management,the assessment of developmentimpacts and the creation ofmitigation plans. It does not give a comprehensive explanation ofcurrent legislation, and readers may wish to seek their own legal advice.

7The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

Widespread populations

Scattered populations

Inventory record

Reintroduction site

Figure 1 Dormouse distribution. Originally dormice were widespread over most of England and Wales, but they are now found only in the shaded areas. Circles show records from the national dormouse inventory, collected since 1990.Stars show sites of reintroductions carried out as part of the Biodiversity Action Plan. This map can help to predict thelikelihood of finding dormice in an area.

8

9The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

1 Introduction: dormice and issues they raise

entirely absent from Scotland. Themost northerly location is nearHexham in Northumberland, with atleast three more sites in Cumbria.Dormice are now either absent orvery thinly distributed in mostmidland and many southerncounties. In Wales dormice havebeen found in a few widelyseparated areas in every countyexcept Anglesey (Jermyn,Messenger & Birks 2001).Although it is still uncommon, thedormouse appears to be relativelywidespread in southern Englishcounties but, because of itsspecialised habitat requirements, it is never as numerous as woodlandrodents such as the wood mouseApodemus sylvaticus and bank voleClethrionomys glareolus. Even incounties where it is widespread, thedormouse has a very patchydistribution. It is particularlyassociated with deciduouswoodland, but also occurs widely inspecies-rich hedgerows and scruband sometimes in other woodyhabitats. The total adult populationis now thought to number about45,000 (Battersby 2005), distributedamong a variety of widelyfragmented sites.

Hazel dormice are sensitive toweather and climate, both directly and indirectly, throughtheir specialised feedingrequirements. They areparticularly affected by habitatdeterioration and fragmentationand also by inappropriate habitat

management. For these reasons,they are highly vulnerable to localextinction. They are consequentlygood bioindicators of animal andplant diversity: where dormice arepresent, so are many other lesssensitive species. The successfulmaintenance of viable dormousepopulations is a significantindicator of an integrated andwell-managed countryside. Theircontinued presence is thereforehighly desirable.

Dormice have full legalprotection, and their presencemust be taken into account whenhabitat changes are likely as aresult of development or changesin woodland management.

This publication is intended to bea practical guide for specialists.Its purpose is:

1 To provide guidance forwoodland managers and others wishing to promotedormouse conservation byactive management of suitable sites and habitats.

2 To provide guidance fordevelopers, foresters and other land managers, whoseactivities may impinge ondormouse habitats.

3 To provide a range ofspecialised references andcontact points for those who wish to know more.

The hazel dormouse is a distinctivenative British mammal that isinfrequently seen owing to its rarityand nocturnal habits. It is rarelycaught in traps or by predators suchas cats and owls, so it is easilyoverlooked even where present.Moreover, it spends most of itsactive time high off the ground andpasses at least a third of the year inprofound hibernation, again makingit unlikely to be seen by the casualobserver. Nevertheless, thedormouse is widely known from itsappealing photographs and itsoccurrence in children’s storybooks (notably Alice’s Adventuresin Wonderland). Formerly it wasalso found by woodland workersduring coppicing and hedge layingoperations, who would often takethese attractive animals home toshow to their children. Thedormouse is therefore a familiarspecies, despite being rarelyencountered in the wild. Like thedolphin, it has the advantage ofbeing an attractive animal with no‘negative’ aspects to its lifestyle.

Over the last 100 years, the hazeldormouse has declined in bothnumbers and distribution. Recentsurveys suggest that it has becomeextinct in about half its formerdistributional range, including sixcounties where it was reported to bepresent by Rope (1885). There arenow fewer than ten known sitesnorth of a line between the Wirraland the Wash (including recentreintroductions), and dormice are

1.1 General introduction

Dormice form a distinctive family of rodents (the Gliridae), which are found widely across

Europe and Africa, with one species in Japan. They are not common anywhere, and by

international agreement they are protected throughout Europe (the Japanese species has even

been designated a protected ‘National Icon’). Two species occur in Britain, the edible dormouse

Glis glis, a squirrel-sized, non-native species that has become a minor pest since its introduction

in 1902, and the hazel dormouse Muscardinus avellanarius – the subject of this manual.

10

1.2 Organisationalframework and support

In the context of dormouseconservation management and the licensing of activities likely to affect this species, the keystatutory organisations are English Nature, the CountrysideCouncil for Wales (CCW), theForestry Commission, relevantsections of Defra (and the WelshAssembly Government) and LocalAuthorities, particularly theirplanning departments. However,dormice also receive considerablesupport from non-governmentalorganisations, many of which areengaged in dormouse survey,conservation and monitoringactivities. Considerable scopeexists for fruitful co-operation withthese bodies, perhaps avoidingunnecessary duplication of effortand actively advancing theconservation of dormice. Furtherdetails of organisations involved indormouse conservation are givenin Chapter 10, and details of legalprotection in Chapter 6.

11The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

In order to understand the potentialeffects of management ordevelopment work on dormice andto help plan effective managementor mitigation measures, it isessential to understand the ecologyof these animals. It is not possibleto offer ‘one size fits all’prescriptions for action in everycircumstance. Instead, byunderstanding the principlesunderlying dormouse ecology, and the reasons why they havebecome nationally rare, it shouldbe possible to adjust proposals tofit local situations. English Natureand Planning Authority staff mayalso find this approach helpful.Specialist consultants should gaindeeper insights through their ownfieldwork or by attending suitabletraining sessions (organised by The People’s Trust for EndangeredSpecies and/or The MammalSociety). However, this section isnot intended to be a comprehensivereview of dormouse biology andsources of more detailedinformation are listed in thebibliography (Chapter 12).

Only part of the 1.3 million ha ofwoodland in England and Wales iscurrently known to have dormiceand some (for example, wet carror woods at high altitude) are veryunlikely to be suitable. Coppicewoodland is generally perceived

as potentially optimal for dormicebut represents only 20,000 ha ofthe 700,000 ha of ancient or semi-ancient woodlands. Afurther 160,000 ha of ancientwoodland was converted duringthe 20th century to plantations ofconifer (50 per cent), broadleaf(28 per cent), or mixed woodland(22 per cent). Plantations that arenot recorded as ancient woodlandsites make up another 300,000 ha,and consist mostly of conifers.Dormice can inhabit Plantationson Ancient Woodland Sites(PAWS) and also new plantations,even quite small ones, especially ifthey are strongly linked to othersuitable habitat including scrub,bramble or gorse.

The dormouse is a nocturnalanimal that lives mainly indeciduous woodland and scrub,where it feeds among the branchesof trees and shrubs. Except forhibernation, it rarely descends tothe ground and is reluctant tocross open spaces, perhapsbecause of the danger posed byowls and other predators. It feedson a wide variety of arborealfoods (Richards and others 1984),including flowers (nectar andpollen), fruits (berries and nuts)and some insects (especiallyaphids and caterpillars). They willalso eat buds and young leaves,

but cannot efficiently digest largeamounts of mature leaves as theylack a caecum in their digestivesystem. In the autumn there isabundant food in the form ofberries and nuts, but these are notgenerally ripe before aboutAugust. So, in the early summer,the dormouse must move from onetree species to another as thedifferent flowers becomeavailable. When these are over,but fruits are not ready, there is aperiod of potential food shortage.At this time, insects may becomeimportant in the diet, but insects(particularly aphids andcaterpillars) are also consumed atother times. It follows that a highdegree of diversity among tree andshrub species is desirable in orderto ensure that an unbrokensequence of foods is availablethroughout the summer. Certaintree species are particularlyvaluable as providers of food atdifferent times of year (see Table1). Hazel appears to be animportant provider of insects, andits nuts form the main food usedto fatten up for hibernation.Where hazel is scarce or absentsmaller fruit seeds, such as thosefrom hornbeam or blackthornsloes (Eden & Eden 2003) maysuffice, but offer less food inexchange for the gnawing neededto open them.

2 Introduction to dormouse ecology

Although traditionally associated with hazel, dormice actually occur in a wide variety of woody

habitats, ranging from ancient semi-natural woodlands with hazel coppice and standard oaks,

to species-rich scrub. They are also increasingly reported living in hedgerows, areas of

plantation conifers and rural gardens. They may even be found occasionally in heathland Culm

grassland and other habitats where these occur close to woodland. Some of these sites may

well comprise sub-optimal habitat, with low densities of dormice present, but others often

harbour significant numbers. Their absence should not be assumed simply on the basis of a

‘non-typical’ habitat.

2.1 Understanding dormouse habitats and ecology

Hazel Where present, this is the principal source of food (nuts) for fattening up prior to hibernation. Hazel also supports many insects, including caterpillars, which are potential dormouse food. Hazel forms a continuous understorey of sprawlingpoles, easy for arboreal activity and is a very valuable (but not essential) species for the dormouse.

Oak

Honeysuckle

Bramble

Sycamore

Ash

Wayfaring tree

Yew

Hornbeam

Broom

Sallow

Birch

Sweet chestnut

Blackthorn

Hawthorn

Conifers

Other species such ascherry, crab apple, holly, ivy.

An important source of insect food (including caterpillars). Dormice also eat oakflowers, but acorns are of little value.

The plant’s finely shredded bark is the preferred nesting material used by dormice.Honeysuckle flowers also provide food at a time when few other things areavailable, with berries later. The climbing strands also offer convenient routes intothe trees and provide dense shelter in which to nest.

Its flowers and fruits are very important dormouse foods and tend to be available for a long period (especially where the site has slopes which vary the amounts ofsunlight on the shrubs) and the thorns provide good protection for nests.Bramble often flowers late, when many other species are over and dormice also eat the berries and seeds in autumn. Dormice seem to thrive where blackberries are abundant, even in the absence of hazel. Bramble is best if scattered amonghazels and trees.

A valuable source of insect food and pollen. A useful tree: dormice can survive inhabitats with many sycamores. However, sycamores cast a dense shade whichreduces the understorey. Thus sycamores should be kept few and scattered, perhapscoppiced to prevent seeding and to reduce the extent of shading.

Ripening seeds (‘keys’) are eaten whilst they are still on the tree, but ash supportsfew food insects. The canopy does not cast a dense shade, but generally ashwoodlands are not good habitat.

Fruits in late summer when little else may be available. Dormice eat the seeds andprobably also the flowers.

The fruits are a favoured food and dormice will make special excursions to reachthem, but the seeds are not eaten.

Seeds are small and hard, but dormice eat them. The advantage is that they are toosmall to be attractive to squirrels, so they may form an alternative food wheresquirrels have taken most of the hazel nuts. Fruiting is erratic.

Flowers are eaten in early summer.

Unripe seeds are eaten from the flowers in early summer. Sallow also supports manyinsects.

The catkins are over too early in the year to be much use to dormice, but they can eatthe seeds. These are too small to attract squirrels and may provide support wheresquirrels compete for hazel nuts.

Chestnuts are an excellent food source and dormice may also eat the flowers.

Fruits (kernels) are eaten but the flowers come too early in the year. Denseblackthorn thickets tend to be avoided where alternative shrubs are available.

Flowers are an important food in the spring. The fruits are eaten occasionally.

Little is known about the use made of these trees by dormice, but they often supportmany aphids and caterpillars – potential dormouse food. The trees may also provideshelter from the wind and rain in exposed sites.

Little is known about the value of these trees to dormice, but it is likely that they willeat the pollen (stamens) and perhaps fruits. Ivy is a useful source of food insects andits evergreen tangles among tree branches are often used for summer nesting sites.

Table 1 Trees and shrubs of value to dormice

12

In addition to hazel, oak, brambleand honeysuckle are especiallyvaluable food sources, butdormice can survive without atleast one of them if an appropriatesubstitute is available. Most gooddormouse sites will have most ofthese species, but the absence ofany, or even all, of them is notevidence that dormice are alsoabsent. Nevertheless, theassociation between dormice andhazel is particularly strong and isrecognised by the animal’s Latinname ‘avellanarius’, which means‘hazel’. The majority of dormousesites include hazel, but this doesnot mean that dormice occur onlywhere it is present. On thecontrary, they can sometimes befound living among other woodyspecies, even conifers. They alsooccur in species-poor habitats suchas areas of secondary growthdominated by sycamore. Howeverthese sites often constitute sub-optimal conditions in which thepopulation is likely to have arrivedrelatively recently and may not besecure in the long term as thehabitat matures. The occurrenceof dormice in such sites, and evenoccasionally in gardens, shouldnot imply that these are corehabitats, nor distract from the needfor appropriate conservationmanagement elsewhere.

Dormice do not normally travelfar from their nest (usually lessthan 70 m), so the different treesand shrubs necessary to maintain asequence of foods through theseasons must be present within asmall area. This implies that avery mixed habitat is desirable.Dormice are highly arboreal, so itis also important that the animalsshould be able to move easilyfrom tree to tree without comingto the ground, and that they shouldbe able to climb between theunderstorey and canopy withoutdifficulty. A continuous shrublayer is ideal, especially wherethere are a few larger canopytrees. It is essential that the treecanopy does not cast too muchshade. Heavy shading means the

understorey will fail to fruitvigorously and may even besuppressed, reducing or removingkey sources of dormouse food.As a rule of thumb, if visibility in high summer at eye level ismore than about 20 m, the shrublayer is likely to be thinning out,and deteriorating as dormousehabitat. Conversely, the bestwoodland habitats are usually indense understorey thickets (wherevisibility is severely restricted),especially those incorporatinghazel. Dense thickets offer three-dimensional arboreal routesthrough the habitat, providingaccess to the tree canopy and avital alternative to activity on theground. Scrub and sprawlinghedgerows often meet thesecriteria and benefit from fullexposure to sunshine, maximisingpotential dormouse food and oftensupporting substantial populations.

Thus it is important that thephysical structure of the habitat isappropriate as well as providing asufficient variety of woody plantsto supply a succession of foods aseach becomes seasonallyavailable. Although tall, shadedspindly growth can sometimessupport dormice, it is a poorhabitat for them compared to anopen tree canopy over well-litdense shrubs which is ideal.The best canopy trees are oaks,with hazel and bramble providingthe best understorey so long asshading is not heavy enough tocompromise their fruiting. Radiotracking studies suggest that innorthern sites, the vegetation isless productive, forcing thedormice to enlarge their homerange in order to obtain sufficientfood. This uses up more energyand adds to the problems they facefrom inclement weather conditionsand lower ambient temperatures.

Although they may weave their ownnests (up to the size of a grapefruit)in bushes and shrubs, dormiceprefer to use more robust restingplaces such as hollow tree branches,squirrel dreys and old bird nests.

13The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

Tree hollows tend to be scarce inBritish woodlands particularly incoppice, in young plantations and in the vigorous undergrowth thatprovides the best feeding areas fordormice. Hence there is a need forolder trees and shrubs with hollowsand rotten branches to be available.Hollow tree stumps and coppicestools may also be used ashibernation sites. Nest boxes are aparticularly attractive substitute fornatural tree holes and, where boxesare provided, a high proportion ofthe dormouse population may usethem. Provision of nest boxes canincrease the local populationdensity, suggesting that theavailability of nest holes may beone of the factors that limitdormouse numbers. However, nestboxes are not normally used forhibernation.

Summer dormouse nests have alsobeen found in bat boxes and birdnest boxes. Where such boxes areprovided for the conservation ofrare bird and bat species, it wouldbe advisable to either increase thenumber of boxes to ensure thatthere is a surplus or put outdormouse nest boxes as well.

Dormice have a patchydistribution, even within the same woodland. This may beassociated with patchiness in food supplies, but might also be a result of social or territorialbehaviour. Male dormice areterritorial in the breeding period(May to September) and mayattack each other, so thepopulation tends to be spreadthinly. Even the best habitats maynot support more than about fouradult males per hectare. Femalesgive birth to (usually) four or fiveyoung, from early June untilSeptember (but mainly in July orAugust). The young remain withtheir mother for up to two months,delaying her production of asecond litter. If young are borntoo late in the summer they maybe unable to reach a viable weightof 15g by late October beforehibernation is forced upon them.

14

Maintain and enhance speciesdiversity in the shrub layer.Some mature trees standamong shrubs, providing accessto the tree canopy.

Log piles providesummer and winternesting sites.

Dense regrowthof spindly treesshould bethinned toreduce shading.

Dense regrowthof spindly treesshould bethinned toreduce shading.

Corridor of trees and uncut shrubs

links coppice blocks.

Areas of maturecoppice, ideally12-20 years old.

Coppiced sycamore provides abundant insect food without scattering seeds everywhere.

Dead hedgingsurroundsregrowing coppicestools to protectthem from deer.

Figure 2 Features of good dormouse habitat management. The best habitat for dormice is in actively coppiced ancientwoodland that maintains a rich herb and shrub layer below an open canopy.

15The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

Honeysuckleleft in place.

Bramble regrowth providesflowers and fruit over an

extended period.

Tree branches meet at narrow pointsalong rides, allowing dormice to

cross without descending to the ground.

Ivy left on trees.

Some clusters of treeshave linked canopies.

Newly cut coppice besideestablished coppice.

Standards are generally widelyspaced to avoid shading theunderstorey.

16

It is unlikely that such smalljuveniles will survive the winter,having run out of fat reserves beforeeffective feeding becomes possibleagain in the spring. Thus, althoughsome females may breed twice in aseason, it is unlikely that they willraise more than one litter per year.The age of the young – in days –may be estimated by taking theirmean weight (up to 8 g), subtracting1 and dividing by 0.16 (see Chapter 8). Sometimes femalesmay aggregate their families into a crèche, with up to nine youngpresent at once. Individual malesmay share the same nest box withthe same female in two successiveyears, implying a long-term pairbond and perhaps more complexsocial behaviour than is normal forsmall rodents.

During the winter, when little foodis available, dormice save energy bygoing into hibernation. Havingspent all the summer in trees andshrubs, they now descend to theground and stay there all winter. A small tightly woven nest is madeand the animals usually spend thewinter there alone. They hibernateunder logs, under moss and leavesor among the dead leaves at the baseof coppice stools and thick hedges.Dormice choose a moist place tohibernate, where the temperaturewill remain cool and stable and thehumidity high. Cool conditions arevital as metabolic processes areslowed at lower temperatures andfat reserves will then last longer.Damp conditions are also necessarybecause water vapour is lost duringthe animal’s breathing. Hibernatingin a moist place will ensure theanimals do not desiccate during thewinter, as they do not wake up anddrink regularly.

Hibernation begins when thenights become cool in the autumnand there is little food left in thetrees, generally around the time ofthe first frosts. Larger dormice(weighing up to 40 g) appear toenter hibernation earlier, whilesmaller animals continue to feeduntil later in the autumn. These

may remain active until Decemberin mild years, especially in thesouth of England. Once inhibernation dormice do not usuallyleave their nests until thefollowing spring (other hibernatorssuch as bats and hedgehogs oftenmove about and feed during thewinter months). Dormice do notnormally hibernate successfully in nest boxes because thetemperature inside is too variable.

During cool or wet periods insummer, dormice may spend severalhours a day in a state of torpor. Inearly summer, more than nine hoursper day may be spent in torpor,although by autumn the averagetime is less than half an hour. Theanimals become moribund andinactive as the body cools, with theirnormal temperature (similar to our own) falling to little above thatof their surroundings. The torpidanimal is tightly rolled up with thetail curled over its belly and face.Torpor economises on energy

expenditure, but at the cost ofdelaying breeding, often until longafter other woodland mammals havealready raised young. Early in theseason, dormice may go torpid inflimsy nests, from which they areeasily dislodged by the wind. It isnot uncommon to find a torpidanimal lying on the ground in theopen, on a footpath for example. Insuch cases the animal is best movedto nearby shelter and allowed towake up and look after itself.

Dormice are highly sensitive to theweather and on cold nights willabandon their nocturnal feedingearly. A 5 °C fall in air temperaturemay result in feeding activity beingcurtailed by an hour or more. Inaddition, dormouse fur is very fineand poorly suited to throwing offwater droplets, so rain and drizzleare a danger to these animals,whereas mice and voles, with adifferent fur structure, are betteradapted to cope. In the autumn,when nights are cold (below 9 °C

Figure 3 Hibernation nest. After being arboreal all summer, dormice retreat tothe ground to hibernate. They weave a tight ball of grass or other fibrousmaterial and pass the entire winter hibernating in the same place. Hibernationsites are chosen that are cool and moist, such as under moss or leaf litter, incoppice stools or under brushwood.

17The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

at midnight), dormice will oftencompensate for reduced nocturnalactivity by coming out during theday. The unpredictable Britishclimate thus affects dormicedirectly, but it also has indirecteffects through their food supply.Warm sunshine stimulates the flowof nectar, helps to ripen fruits andspeeds the growth of insects, allproviding richer food supplies.Conversely, cool, cloudy conditionsretard the production of dormousefood. In some years the majority ofsummer days may be dominated bycool, wet ‘westerly’ weatherconditions, probably affecting theability of female dormice to raisetheir young and also reducing theviability of independent juveniles.This may limit their success,especially in northern areas at theedges of their natural distribution,on higher ground and in moreexposed sites. In such places goodhabitat management becomes evenmore important.

It is likely that a succession of badyears, with inclement weather andpoor breeding success, has created aseries of historical bottlenecks inthe dormouse population. Thiswould be particularly dangerous forsmall isolated groups of animals,whose numbers may then bereduced to a non-viable level,resulting in local extinction. This islikely to have happened more oftenin the north of England than thesouth (where weather conditions aregenerally more favourable), and it isin the north that the greatestcontraction in dormouse distributionhas occurred and where dormice arestill declining. The same principlesapply in microcosm to hilly sites.Habitats on south facing slopes arelikely to be better for dormice thanthose with a shaded, northerlyaspect. Narrow valleys, particularlywith a north-south orientation wheredaily exposure to direct sunshine isbrief, are likely to be inferiorhabitats compared to more gentleslopes. However, a varied localmicrotopography may beadvantageous because the diversityof conditions and variation in

exposure to sunshine will result inextended fruiting and floweringseasons, providing dormice withmore feeding options.

2.2 Dormice in other habitats

The best conditions for dormice areto be found in extensive ancientsemi-natural woodland, where therehas been time for shrub speciesdiversity to develop, and wherecoppicing of hazel is carried out ona long rotation. This appears toconstitute the species’ core habitat,especially where shrubs flourish inclearings and around woodlandedges. However, this does notmean that dormice occur nowhereelse, nor does it imply that otherhabitats are necessarily poor.Indeed, some types of scrub, youngplantation and hedgerow offerexcellent conditions, partly becausethey are unshaded and highlyproductive. Such sites maytemporarily even have moredormice than an equivalent area ofancient semi-natural woodland.Occasionally dormice are found ingorse scrub, heathland and even inalder trees among reeds. They havealso been found in gardens amonghoneysuckle or hibernating inclumps of pampas grass. However,these unusual occurrences shouldnot distract from focussing on whatis normal. At the same time, theexceptions indicate a need to beaware that dormice do occur in awide variety of sites and the needfor survey and consideration shouldnot be overlooked simply becausethe habitat comprises somethingother than ancient semi-naturalwoodland. Moreover, theoccurrence of dormice in ‘non-typical’ habitats may indicate thepresence of a thriving population ofthese animals in adjacent areas.

2.2.1 Scrub

In some areas dormice can be foundflourishing in scrub (Eden & Eden1999), but such habitats tend to berelatively ephemeral (beingsucceeded by high trees in time).Scrub also often develops as a

successional advance on previouslyopen ground when, for example,grazing ceases. Where such sitesare isolated by open ground, theyare less likely to become colonisedby dormice, irrespective of theirhabitat quality. Moreover, wheresuccession takes place on openground, the trees or shrubs tend tobe of similar age and grow at highdensity. For some years, this mayform good dormouse habitat, but intime, competition for light and spaceamong the shrubs and saplings oftenresults in tall, spindly growth. Afterabout 10 to 15 years, this may beginto offer poor potential for dormiceand the dense shade cast by thetaller trees may reduce the viabilityof the understorey. Nevertheless,scrub can provide excellentconditions for dormice.

2.2.2 Conifers and plantations

Despite the importance of shrubdiversity and abundant sunlight,dormice are sometimes discovered(frequently so in some areas) in therelatively uniform conditions ofplantations, particularly where theseconstitute Plantations on AncientWoodland Sites (PAWS). Surveysindicate that dormice may occur inup to 85 per cent of PAWS that have hazel present. Often thedormice occur where conifers havebeen planted into existing deciduouswoodland or scrub and they may bepersisting despite increased shadingas the conifers grow. Plantationsthat are at the scrubby pre-thicketstage or have not been ‘cleaned’(that is, broadleaves removed duringthinning) probably have a muchhigher chance of having dormousepopulations. However, some sitesappear to support dormice in thevirtual absence of deciduous treesand shrubs. It is difficult to see how they manage, but certainsoftwood species may well supportsufficient insects (aphids andcaterpillars for example) to sustain a small dormouse population in theabsence of more conventional food.It is also possible that dormice canmake use of sap as a food source insuch habitats.

It is important not to assume thatdormice will be absent fromplantations and conifer-dominatedhabitats (especially where somedeciduous species are present).Nevertheless, nationwide, theirpresence is unusual and isespecially unlikely in uplandconifer plantations. It is currentpolicy for conifers to be removedfrom many ancient woodland sitesand the possibility that dormicemay be present should not beoverlooked. Suggestions forappropriate survey andmanagement are described later.

2.2.3 Hedgerows

Dormice also live permanently insome hedgerows which provide acontinuity of foods throughout theactive season. If they areunshaded, hedgerow shrubs oftenfruit well and thus offer abundantfood for dormice. Hedges are also

important dispersal routes, a vitallifeline linking dormousepopulations in small copses. Thebest hedges are those with a highshrub diversity, a feature ofancient hedgerows, although somerecent hedges may also be verydiverse. Hedges need to be cutregularly if they are to remaintight and stock-proof, but cuttingevery year drastically reduces theavailability of flowers and fruits(for example hawthorn) that areborne on new wood. Even cuttingat 5-year intervals may removemost of the fruiting hazel.However, unmanaged hedgesbecome outgrown and oftendevelop gaps, reducing their valueas dispersal routes. Probably thebest compromise is to cut onlyshort sections of hedge at a time,or perhaps alternate sides of thehedge at 3 to 5 year intervals(though this may not be practicalin many circumstances).

2.3 Problems with smallpopulation size

Dormice live at low numbers,even in the best habitats. In early summer there are typicallyonly 3 to 5 (but sometimes up to10) adults per ha in deciduous and conifer habitats. The National Dormouse MonitoringProgramme suggests an average of between 1.75 and 2.5 adults per ha based on 83 sites in various habitats, with the lowestdensities in the north of England(1993 to 2000 inclusive; Bright & Sanderson, pers. comm.).Across the country, including sub-optimal habitats, the averagepopulation density is only about2.2 per ha. Thus small woods will contain few dormice, perhaps not enough to constitute a viable population unless the site is connected to a larger area of habitat.

18

Species Habitat Mean spring density(individuals per ha)

Source

Table 2 Small mammal population densities (pre-breeding numbers of adults per ha). Autumn densities may be severaltimes higher.

Optimal habitat (diversedeciduous woodland withabundant scrub and vigorousunderstorey)

4 to 10 adults Bright, pers. comm.DormouseMuscardinusavellanarius

Oak dominated woodland, with hazel

2 adults, increasedby 48 per cent byappropriatemanagement

Bright & Sanderson,pers. comm.

Dormouse

Scrub unknownDormouse

Conifer woodland 1 to 3 adults Trout, pers. comm.Dormouse

Hedgerow 1.3 adults Bright & MacPherson,2002

Dormouse

Deciduous woodland 40 plus Corbet & Harris, 1991Wood mouse(Apodemussylvaticus)

Woodland Up to 130 Corbet & Harris, 1991Bank vole(Clethrionomysglareolus)

Nobody knows how few is too few,but clearly a ‘population’ of lessthan about 20 animals, only half ofthem females, is very vulnerable tochance extinction as a result ofaccidents, inbreeding or poorbreeding success. Small woods ofless than 20 ha often provideexcellent habitat (because of lackof shading and large areas ofshrubby edge habitat), but if theyare not linked to other sites nearbythey probably contain too fewdormice to sustain a permanentlysecure population. Even with good

habitat, surveys show that woodssmaller than 20 ha are less likely tocontain dormice than larger sites,unless they are linked to otherareas of suitable habitat.Fragmentation of large sites istherefore damaging and it isimportant that if small patches ofwoodland are created as a result ofdevelopment projects or roadconstruction, for example, thenremnant woodlands should belinked by woodland strips orhedgerows to facilitate dispersaland effectively increase the

continuous population of dormice.Isolated woods, even quite largeones, are likely to lose their dormicein time. Species-rich hedgerowsoffer good habitat and may be anessential means of dispersalbetween woodland sites, reducingthe isolation effect of small woods,as well as providing suitablehabitat for permanent occupation.However, dormice will cross openground occasionally, so it shouldnot be assumed that small siteslack dormice simply because theyare isolated.

19The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

Table 3 Major threats to dormice.

3 Loss of woodland habitat Many areas of diverse ancient woodland have been felled andreplaced by farmland, roads and urban developments. Replantedwoodland has fewer tree and shrub species present, and thesetrees and shrubs will be of a similar age. Planted coniferssometimes support dormice.

2 Heavy shading and lack ofthinning

Canopy trees compete for the light, suppress the understorey andcreate a dark woodland with tall spindly trees and little dormousefood; generally an unsuitable habitat for dormice.

1 Decline in coppice management Ultimately results in heavy shading, suppression of regrowth anddeath of the understorey where the dormouse obtains most of its food at certain times of the year.

7 Climate change andunpredictable weather

Variable and unsuitable weather reduces breeding success andsurvival, making extinction more likely if other factors are less thanideal. This is likely to be a particularly sensitive problem innorthern counties, at sites with higher elevations and in exposedsites. Bad weather, leading to poor breeding success seriouslythreatens small isolated populations. Three bad years in a row maybe sufficient to cause local extinction. The effects of future climatechanges are difficult to predict.

6 Deer and squirrels Browsing by deer (and domestic stock) damages shrubs that providedormouse food. In extreme cases suppression of woody regenerationresults, leading to the elimination of dormice. Squirrels compete forfood, but how seriously this affects dormice is not known.

5 Loss of species-rich, infrequently-cut hedgerows

Destroys habitat suitable for permanent occupancy. Removes important food-producing dispersal corridors between woodland sites.

4 Habitat fragmentation andconsequent isolation woods

Large areas of woodland have been progressively dissected intosmaller and smaller copses, by roads and other developments.These woodland fragments often contain too few dormice to beconsidered viable populations. The remaining habitat is left inisolated blocks, often with no woodland or hedgerow connectionsthat would allow the dispersal and exchange of animals betweenlocal populations. Populations of dormice in isolated sites arelikely to suffer from inbreeding in the long term.

20

3.2 Finding evidence ofdormice

The presence of dormice shouldbe assumed in any areas of woodyhabitat (including plantations,hedgerow and scrub) within theirrange (see Figure 1), particularly inthe south of England.

Where development or land-usechange is proposed, only in verylimited circumstances will it beacceptable to submit mitigationplans based on little or no surveywork. An example would be wherethe habitat is both clearlyinappropriate and where thedevelopment’s impact is likely to benegligible. Surveys should normallybe undertaken to detect actualpresence or demonstrate likelyabsence. No area of woodlandshould be presumed to lack dormice,except very small unsuitable copsesof less than 10 ha in extent whichhave poor habitat and are separatedby at least 500 m from the nearest

suitable habitat. However, sincedormice are known to occur in sometypes of amenity woodland, coniferplantations and scrub, as well asdeciduous forest, the surveyprocess should not be eliminatedsolely on the grounds that thehabitat is ‘unsuitable’.

Where local surveys areundertaken in order to find newlocalities, enquiries among catowners, farm workers and throughthe local newspaper may elicituseful information. Pictures ofdormice should be used in order toavoid following up reports basedon mistaken identification. Owlpellets rarely contain dormouseremains (less than 1 per cent of allowl prey items in Britain), butskulls can be easily identified asthe teeth have distinctivetransverse ridges, not knobblysurfaces as in mice, or bold zigzagpatterns as in voles. Dormice alsohave four cheek teeth, not three asin mice and voles. Where specific

sites need to be surveyed, suitablemethods should be employed.

3.2.1 Traps and baiting points

Dormice do not normally entersmall mammal traps (for example,Longworth traps), even where theseare set in trees. American Shermantraps, baited with apple, are moresuccessful (but expensive) and wiremesh cage traps are better still(Morris & Whitbread 1986). Traps can also be made from plastic rainwater pipe (details fromthe Vincent Wildlife Trust).However, traps must be visited atleast once every day (unlike nestboxes or nest tubes). Trapping isboth time consuming and relativelyunproductive, as dormice live atlow population densities. It istherefore an inefficient survey tool and not recommended.Trapping requires a licence from the appropriate authority (English Nature or the Countryside Council for Wales).

3 Finding signs of dormice andmonitoring numbers

For sites within the distribution range of the dormouse, the only certain way of determining

their presence is by survey, using the methods described below. Dormice have been found in

small woods (even down to 2 ha where other suitable habitat is adjacent) and in woodland

traditionally considered as unsuitable, for example conifer plantations on new sites. These

populations should be encouraged, especially on the fringes of the UK dormouse range. In

some areas, dormouse survival is apparently dependent on conifers in the absence of other

woodland. Dormice could potentially occur in any woodland area, but certain factors affect

that likelihood. This simple guidance is important both for sites with primarily timber-growing

objectives (where normal cost-effective forestry operations will necessarily be carried out) and

for sites with primarily wildlife conservation objectives. In the absence of an existing survey,

a preliminary judgement based on the information in Table 4, supplemented by local

knowledge, may be made. Dormice may be found in woods with several poor characters or

are regularly moving in from an adjacent good habitat. If dormice are known to be present in

all, or part, of a contiguous habitat, they are also likely to be present in neighbouring areas of

connected woodland, scrub etc. (even where these appear to be suboptimal habitat).

3.1 Predicting the presence of dormice

21The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

22

Table 4 Factors affecting the probability of dormice being present on a woodland site within their known range. Thisincludes ancient woodland sites, Planted Ancient Woodland Sites (PAWS) and modern broadleaved or conifer plantations

Increasedprobability

Decreasedprobability

� Large woods: area over 50 ha – very likely; at least 20 ha – likely; between 2 and 20 ha –possible.

� Adjacent to ancient woodland or PAWS (including conifer), scrub or early successional stagewoodland, including conifer.

� Wide range of broadleaved species present, including some fruiting, either in patches, scatteredor at the edge.

� Wide range of ages of trees.

� Species-rich shrub layer, especially with hazel, honeysuckle or bramble.

� Species-rich edge strip or ride sides.

� Thick, wide hedgerow connections to nearby suitable woodland.

� Contains hazel or sweet chestnut coppice – ideally managed in small coupes.

� No thinning history (for conifers).

� Small wood, especially if mostly conifer.

� Old conifer plantation subject to multiple thinning.

� Isolated from other woodland or adjacent only to older conifer plantation already subjected tomultiple thinning.

� Little or no shrub understorey.

� No fruiting broadleaved trees.

� High local deer population suppressing most regeneration.

� Presence of cattle, sheep or pigs.

� Seasonally waterlogged ground.

� Derelict coppice or clear-felled in very large coupes (that is, blocks of woodland) relative to thewoodland area.

� Site more than 300m above sea level.

Figure 4 Dormouse skull and teeth. Dormice have a typical rodent skull with four molar teeth. The transverse ridges are distinctive.

23The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

Smoothed edge

Vole or mouse

Baiting points can be set up (forexample, in cardboard milk cartonsfixed to trees and supplied withpieces of apple). Dormice mayfeed here and leave distinctivedroppings which are usually largerand more crinkly than those ofother small rodents. The problemis that positive identification offaecal pellets requires experienceand is not fully reliable. Milkcartons are not very durable andthe apple bait needs frequentrenewal. This survey method isnot recommended.

3.2.2 Gnawed hazel nuts

The best way to establish dormousepresence at a site is to look forgnawed hazel nuts (see illustrationfor diagnostic features). Althoughthis is obviously impractical wherehazel is absent, it is worthsearching any adjacent areas withhazel to see if dormice are nearbyand thus likely also to be present onthe site under investigation.Several species of rodents openhazel nuts, but only the dormouseleaves a smooth round opening.Dormouse tooth marks will befound around the rim of the hole,smoothing it out, with a few toothmarks on the nut surface. There areno transverse tooth marks acrossthe rim of the nut shell. Dormousetooth marks may be visible to thenaked eye, but use of a magnifyingglass is recommended. Mice andvoles also gnaw holes in nuts, but

To conduct a systematic searchselect an area of heavily fruitinghazel and search a square ofground measuring 10 m x 10 mfor 20 minutes. If no dormousenuts are found, repeat the processin another part of the site. Thereis an 80 per cent probability that,if dormice are present, thecharacteristically gnawed nuts will be found by the time threesuch squares have been searched(Bright, Mitchell & Morris 1994).If five squares fail to yielddormouse nuts, it is about 90 per cent certain that dormice arenot present, although this is stillnot proof of absence from the site, especially in the north where dormice are particularlysparse. Heavy nut consumptionby squirrels can result in ‘falsenegatives’, so where relatively few nuts (less than 100) are found that have been opened byspecies other than squirrels – andnone have yet been found openedby dormice – it is appropriate toincrease survey effort by searching up to a further fivesquares.

An alternative way of achievingan adequate sampling intensity(W. Cresswell, pers. comm.), is to collect 100 hazel nuts that have been opened by smallrodents (voles and mice, butavoiding caches made by thesespecies and also ignoring nutsopened by squirrels). If thissample contains no nuts that have been opened by dormice it is highly probably that dormiceare not present.

Fresh hazel nuts show tooth marks much more clearly thanolder ones. It is thus best to carry out nut searches from aboutmid-August (when the nuts firstaccumulate on the ground), andpreferably before Christmas.Hazel nuts will persist on theforest floor for over a year, butgradually decay so that toothmarks become progressively lessdistinct and it is harder to decidewhich species gnawed the nut.

these are generally irregular inshape and have a different patternof surrounding tooth marks.However, most hazel nuts areopened by squirrels which shatterthem and leave a sharp, jagged andirregular opening to the nut.Squirrels will also split nuts in halfor slice off portions of the shell,leaving a large (usually oval) hole.Small round holes (only 2 mmdiameter) are the work of weevilsburrowing out. Nuthatches andother birds may peck holes in nuts,but they are irregular in shape andoften splintered at the edges, notsmooth. Where whole slices of nutshell have been removed, tiny pores(like pin pricks) are often visible inthe cut edges. This is clearevidence that the nut was notopened by the gnawing action ofsmall rodent teeth, which tends toobliterate these minute pores.

Dormice gnaw nuts up in thecanopy, dropping shells to theground below. Their nuts willtherefore tend to be scattered andmore often found below the hazelcanopy rather than close to thebase of a tree or shrub. Mice andvoles often collect nuts intocaches, dormice do not. Casualsearching for nuts is oftensufficient, but a systematic searchmakes it easier to be confident thatan absence of shells is due toabsence of the animals rather thanaccidental failure to find thecharacteristically gnawed nuts.

Dormouse

Figure 5 Gnawed hazel nuts. Dormice leave a smooth round hole with fewtoothmarks on the surface. Mice and voles may also leave a round hole, butwith transverse toothmarks on the cut edge.

24

Searches carried out after aboutEaster may need increased searcheffort to be effective, owing to theincreasing proportions of nuts inwhich the characteristic toothmarks cannot be recognised withconfidence.

Sometimes there is too littleheavily-fruiting hazel to conductthe kind of surveys describedabove In these cases it isappropriate to check otherlocations more suitable for nutsearches that are connected to the site by features along whichdormice would be expected tomove (for example, hedgerows).Should these prove to harbourdormice, then a precautionaryapproach should be taken to thesite being investigated. Thisapproach has particular meritwhen dealing with lineardevelopment schemes such aspipelines or new roads, which may affect large numbers offeatures such as hedgerows,patches of scrub and belts ofwoodland, all of which could beused by dormice and are difficultto sample by nut searches.

3.2.3 Nests

Where hazel is absent, other signsof dormice must be sought, suchas nests. Dormice may sometimesbe discovered asleep in old birdnests, tangles of ivy or masses ofconifer needles trapped amongbranches. They also weave theirown nests. Typically theseare grapefruit-size and oftenfound in brambles or otherlow-growing shrubs and aremost likely to be found inthe autumn. Dormousenests are woven fromstrips of honeysucklebark, or similar material,and frequently havewhole leavesincorporated into theouter layers. These areoften collected freshand are either green orfaded to grey. The nestsare spherical and lack an

obvious entrance hole. Thisdistinguishes them from a wren’snest or harvest mouse nest, both ofwhich have a distinct entrancehole and are normally mademainly of shredded grass. Harvestmouse nests incorporate theshredded leaves of the grass stemsto which they are attached and aretennis-ball size. Unlike dormouse

Figure 6 Summer nest. These are sometimes built in low brambles or othershrubs. They are about the size of a grapefruit, have no obvious entrance holeand usually have a covering of leaves over the woven honeysuckle core.

Figure 7 Hair tube taped to a branch. When an animalsqueezes through the baited tube it leaves hairs attachedto the sticky tape that covers the holes in the roof. One ofthese is peeled back to show the hairs attached.

nests they do not usuallyincorporate tree leaves. Searchingfor nests is time consuming andoften unsuccessful – even wheredormice are known to be present –as they mainly use other places torest (for example, tree holes) anddo not often construct nests oftheir own. Thus, failure to findwoven nests should not be used asevidence of absence.

3.2.4 Hair tubes

Hair tubes are simple to use andcheaper than nest boxes (seebelow). They can be made fromplastic sink-outlet pipeapproximately 3 to 4 cm diameter.Two 25 mm square openings mustbe cut in the 'roof' with a saw andchisel, then adhesive tapestretched across each opening withthe sticky surface facing inwards.The tubes, baited with jam orpeanut butter, are then fixed tohorizontal branches using string,cable ties or sticky tape.

As the dormice (or other smallmammals) squeeze through the

25The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

tube to get at the bait, they leavehairs stuck to the sticky tape.After a few days, the tapes can becollected. Hair samples may beacquired from mice, voles andshrews, not just dormice, and amicroscope is needed to tell themapart. This is not difficult, withpractice, and will be made easierby having comparative samplesmounted on glass microscopeslides. Dormouse hairs tend to bevery fine, much thinner than miceor voles. Under the microscopeeach hair has a ‘uniserate’ medulla(inner portion) that looks like aladder of single blocks. Shrewhairs look similar but are darkerand thicker. Mouse and vole hairshave a multiserate medulla, withseveral adjacent rows of blocks upthe middle of each hair (SeeFigure 8).

The success rate of hair tubes islow. Fewer than 10 per cent oftubes may catch dormouse hairs,even where the animal isabundant. Their advantage is thatthey may yield results within aweek, whereas nest boxes need tobe put up and left, often formonths, before they are found andused by dormice. Hair tubes arealso easier to set up among thebranches of dense shrubs andtightly trimmed hedges. They arealso cheap, so large numbers canbe put out, increasing theprobability that dormice will bedetected. Because of their lowsuccess rate, hair tubes should beused in large numbers. A densityof at least twice that for nest boxes is recommended (seebelow). Their relative inefficiency suggests that this isnot a good survey method andabsence of hairs in the tubescannot be accepted as evidencethat dormice are not present

3.2.5 Nest boxes

Wooden nest boxes, similar to bird boxes, but with the entrancehole facing the tree, are readilyused by dormice and offer ameans of detecting the animals in

the absence of gnawed hazel nuts. They are also an importantconservation tool and evidentlyboost the local dormousepopulation density (Morris andothers 1990). Those put up nearhoneysuckle are more likely to be occupied.

Although nest boxes will revealthe presence of dormice, they areoften not used immediately.Sometimes they remain empty forseveral years. Often the first signswill be nests rather than theanimals themselves. Dormousenests are woven with a ‘roof’(even inside a nest box), and theyfrequently incorporate greenleaves collected from the treecanopy above. These tend to fadeto a greyish colour as they dry out,distinctly different from darkbrown dead leaves collected fromthe ground by other species.

Figure 8 Small mammal guard hairs.Shrew hairs (top) are uniserate withdistinctly rectangular cells. The hair isblack and very fine. Dormouse hairs(centre) are also uniserate, but withmore rounded cells. The hairs are fineand sandy coloured. Mouse and volehairs (bottom) are thicker and have amultiserate medulla.

SpacingBars

Entrance

3 cm

A wire loop holdsthe box onto thetree

A wire hook onthe back of thebox holds the lidin place (not shown)

Front of roof projects forwardthe same distance as spacers

Figure 9 Nest box. Dormouse boxes are like bird boxes, but with the entrancefacing the supporting tree or branch. Spacing bars above and below theentrance allow easy access to the entrance hole, which is about 35mm indiameter. The dimensions of the box are not critical. Boxes should be attachedusing a wire sling, making it easy to take them down for inspection.

Wood mice (and yellow-neckedmice) will also make nests in theboxes, but these are not wovenand have no ‘roof’. When fresh,the nests of mice comprise a loosemass of dead brown leaves thatbecomes reduced to an untidycarpet of brown leaf fragments inthe bottom of the nest box. Birds(mostly great and blue tits) alsouse nest boxes and make a dish-like nest with no top. Their nestsare usually composed mostly ofmoss, hair and feathers, materialsthat the dormouse rarely uses.Invertebrates may use the nestboxes too, including slugs, moths,bumblebees, woodlice and,occasionally, hornets.

Nest boxes need to be used inlarge batches to be an effectivesurvey method. Fifty or moreboxes are recommended, and they should be put up in a grid, spacedabout 20 m apart. A single linealong the edge of a wood mayachieve a higher occupancy rate(due to better quality edgehabitat), but cannot give a reliablepopulation density estimate.Similarly, putting clusters ofboxes in ‘good places’ willenhance occupancy rates andincrease the probability ofdetecting the presence ofdormice, but reduce the potentialfor scientifically validcomparisons between sites.Since they are expensive, nestboxes should be consideredmainly as a means ofpopulation monitoring ratherthan as a survey tool. Furtheradvice on nest boxes canbe found in section 3.4.

Inspecting nest boxes(and nest tubes) requiresa licence from EnglishNature or the CountrysideCouncil for Wales in areas where dormice are already knownto be present. If boxes or tubesare put out speculatively to detectpresence, this in itself does notrequire a licence, but a licence isessential once the first dormousehas been found.

26

Plywood tray slides into box

Platform projects from tube

End block seals tube

Nestchamberarea

Doorstep

Figure 10 Nest tube. The tube is tied tightly to the underside of a suitablebranch with wire. The plywood tray, with attached end stop, slides into theouter tube. Tubes are readily adopted as nest sites by dormice, providing arelatively cheap and easy way of detecting their presence.

3.2.6 Nest tubes

Nest tubes are an inexpensivemeans of detecting dormice inhabitats where nut searches areunlikely to be effective. Nesttubes were first designed for use(in a larger form) with edibledormice, which found them asattractive as much more expensivewooden nest boxes (Morris &Temple 1998). Hazel dormice willreadily use a smaller version,occasionally for breeding as wellas daytime shelter. The smallertubes are made from stiff double-walled black plastic sheet, 5 x 5cm in cross section and 25 cmlong. A small plywood tray isplaced inside, projecting 5 cmbeyond the tube’s entrance toallow the animals' easy access.The opposite end of the tube issealed with a wooden blockmounted on the tray. Tubes can bemade easily but are also available

for purchase from The MammalSociety. They can be suspendedby wire or tape, fixed firmlyunderneath horizontal limbs,where they resemble a hollowbranch. The tubes can be emptiedwithout removing them by placinga plastic bag over the closed endand pushing in the wooden trayfrom the open end of the tube.This will usually dislodge anyoccupant or nest.

Being relatively inexpensive, morenest tubes can be put out thanwooden nest boxes, enhancing theprobability of detecting scarcedormice. They are also lighter tocarry and their slimmer shapemakes them easier to position indense hedgerow shrubs. Theirdisadvantage is that they probablywill not last longer than a fewyears, whereas nest boxes madefrom outdoor plywood maysurvive for a decade or more.

27The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

Being small, they are also lesssuitable than nest boxes forbreeding purposes. Nest tubesshould therefore be considered asan excellent tool for surveys, butnot for long-term populationmonitoring.

For survey work, small numbersof tubes are likely to missdormice, even where they areknown to be present. It isrecommended that at least 50tubes be used to sample a site,spaced at about 20 m intervals(Chanin & Woods 2003). Theyshould also be left in place forseveral months. Nest tubes aremost frequently occupied in Mayand August/September. Timingtheir deployment is thereforeimportant. Setting them out inApril may get early results, whilesetting them out in June may beless immediately successful. It isbest to leave them out for theentire season, from Marchonwards, for checking inNovember. In one survey in SouthWestern England sampling foronly three months (July, Augustand September) detected half thenumber of new nests and resultedin a third of the sightingscompared to a similar survey

made in a full season (Chanin &Woods 2003). See Table 5.

It is possible to set out 100 nesttubes in a single day, provided thattheir siting has been pre-determined and they do not needto be carried far. Checking shouldtake place at monthly or bi-monthly intervals, and under goodconditions 150 tubes could bechecked in one day. The tubesshould be inspected for thepresence of dormice and also forsigns of recently constructeddormouse nests. A long-handledmirror may be helpful in pricklyhedges. Numbering the tubes andsetting them out in order at regularspacing makes this survey methodmuch easier. Data recording canalso be simplified (for example, byhaving pre-prepared data sheetswith numbered grids or lines tonote the contents of each tube).

Using 50 nest tubes as a standardand Table 5 as an index of the‘value’ of different months forsurveying, a score can be devisedas an indicator of the thoroughnessof a survey. Thus, 50 tubes leftout for the whole season scores 25 (the sum of the indices for all 8 months), but 25 tubes left out in

April and May scores only 2.5 (1 + 4, divided by 2 because onlyhalf as many tubes are used).This search effort may sometimesbe enough to detect dormice, butassumed absence should not bebased on a search effort score ofless than 20. This would beobtained by using 50 tubes fromJune to November inclusive(Chanin & Woods 2003).

3.3 Dormouse surveys – goodpractice recommendations

Although it is virtually impossibleto prove that dormice are absentfrom any area of appropriatehabitat within their natural range,an adequate survey will giveconfidence that any significantpopulations have been detected.For environmental assessment ordevelopment sites, surveyproposals should be based on therecommendations in Table 6. Thefollowing is a recommendedapproach to a survey:

1 Check whether the site fallswithin or close to the knownrange of the dormouse (seeFigure 1).

2 Check for the existence ofdormouse records with the local biological records centreor on the National BiodiversityNetwork (NBN)www.searchnbn.net.

3 Check with the site owner tosee if they know whetherdormice are present.

4 If the presence of dormice ispossible, carry out a surveyusing a recommended methodat an appropriate intensity.

5 If dormice are found, submitdata to the local biologicalrecords centre.

Month Index of probability

April 1

May 4

June 2

July 2

August 5

September 7

October 2

November 2

Table 5 Index of probability of finding dormice present in nest tubes in anyone month

28

3.4 Monitoring

Nest boxes are readily used bydormice and provide the onlypractical means of monitoringdormouse populations.

A suitable nest box design is shown in Figure 9. The exact size isnot critical. The boxes are bestmade from marine ply or anotherrot-resistant wood. Make holes inthe floor of the boxes to allowdrainage. Cheaper boxes can be

made using softwoods, though thesewill often deteriorate rapidly. A lifeof three to five years is normal forcheap boxes, whereas boxes madeusing more resistant woods will lastfive to 10 years. Cheaper temporaryboxes are suitable for site surveys,but longevity is important wherepopulation monitoring is theobjective. The wood must not betreated with oily or odorouspreservatives. County WildlifeTrusts, bat groups and the RSPBmay know where to contact local

nest box manufacturers.Sponsorship may be obtained forindividual nest boxes or whole sets.Boxes can be put up at any time ofyear, but ideally should be in placeby May to allow use in the summer.In some areas, the first ones may beoccupied within a month of beingput up, in other places occupationmay not occur until the second year.If three summers pass without useby dormice, then the animals areprobably not present or the boxeshave been badly sited.

Choice

1

Method

Search for gnawedhazel nuts

Recommendations

Most efficient method. Gives quick results, but only where hazel is present.Most useful over winter. Search at least five 10 m x 10 m quadrats; more ifsquirrels have opened most of the nuts (see Section 3.2.2).

Table 6 Survey methods and good practice

Finding dormice in conifer plantations

Sites may be pure conifer or include a wide diversity of habitat, including broadleaved perimeters or mixed-speciesplantings or isolated remnants of a previous broadleaved component within, around or adjacent the plantation.

� If hazel is present it should be inspected for gnawed hazelnuts by the normal survey method.

� Within a conifer Planted Ancient Woodland Site (PAWS), locations near glades – where shrubs are associatedwith a thin canopy – or where there are contiguous broadleaved edges or internal groups are the most likelysites. Analysis of the habitat components near 1000 nest boxes (from 20 conifer sites) shows that presence ofdormice in boxes was closely related to the presence and amount of the shrub layer.

Finding evidence of dormice where no hazel exists may take months or even several years and requires theerection of nest tubes or nest boxes. To determine presence, choose the most likely locations. It may beappropriate to look where PAWS is adjacent to other suitable habitat. If dormice are found nearby in adjacentwoodland or scrub, they are likely also to be in, or at least using, the plantation. Include nearby young scrubbyplantations and other succession habitats containing bramble/gorse/bracken/old-heather and hedges.

6 Trapping Labour intensive. Needs a licence. Low ‘hit rate’. Not recommended.

5 Nest searches Not recommended as a survey method, but nests may well be found whenclearance is in progress.

4 Hair tubes Cheap; limited to summer months; requires hair identification skills. Low ‘hit rate’. Very difficult to quantify search effort. Not recommended.

3 Nest boxes As for nest tubes, but much more expensive and better suited to long-termmonitoring. Use a search effort score of 20 or more (see Section 3.2.5).

2 Nest tubes Good method, especially where hazel absent. Only useful March–November.Likely to take several months at least. Use a search effort score of 20 or more(see Section 3.2.6).

29The dormouse conservation handbook - second edition

It is recommended to clean out all nests at the beginning of eachsummer. Remove bird nests assoon as the chicks have fledged to reduce the risk of infestationwith mites. Wet nests and dampmaterial from the previous yearshould also be removed as theymay harbour nematode parasitesand also hasten decay of the box.Only fresh, dry dormouse nestsshould be left in the nest boxes.Dilapidated boxes should berepaired or replaced before thedormouse season begins aboutMarch or April. It may be helpfulto mark paths with tags to makethe boxes easier to find.

When checking nest boxes, use asmall rag or plastic bag to plugthe entrance hole or cover it withone hand, then open the lidcautiously. If there is a nestinside, close the lid, lift the boxdown and open it inside a largeplastic bag. Any dormice foundshould be sexed and weighed.Unlike other small rodents,dormice rarely bite and so can behandled between palm andfingers, rather than by the scruffof the neck. Take particularcare not to handle them by thetail, as the skin is easily strippedoff and does not regrow.

For long-term monitoring, fifty ormore boxes are recommended.Where estimates of populationdensity (numbers of animals perhectare) are required, they shouldbe put up in a grid spaced about20 m apart, giving a density of 30boxes per hectare. The boxesshould be numbered sequentiallywith weatherproof ink to helplocate them and to permitaccurate record keeping.Numbering the boxes before theyare put up, then setting them outin order, is more efficient thatputting them up first then tryingto find them to number them.Putting boxes out in more-or-lessstraight lines and standardintervals also makes it easiertrying to find them again. It is agood idea to make a map,

showing where each numberedbox is located and what tree typeit is in. The most convenientheight for nest boxes is about 1.5to 2 m off the ground. Higherboxes may be more secure fromvandalism or other interference,but are no more likely to be usedby dormice.

The boxes should be sited inhazel or other shrubs and youngtrees that are linked to theadjacent understorey. Avoidisolated trees or bushes. Attacheach box to a stout branch,suspended in a loop of wire so itcan be easily lifted down andemptied into a large plastic bag.Garden wire or galvanised strandwill do, but plastic covered singlecore copper wire is best as it isslightly elastic and easier tomanipulate. Avoid having theentrance hole pointing upwards asthis allows rain to get inside. Theentrance hole should face the tree,facilitating access by dormice andmaking it more difficult forunintended occupants to enter. It does not matter which compassdirection the box faces.

Check nest boxes at least twice ayear (May and October) to recordany animals present. Howevermonthly checks will provide moreand better quality information,particularly on breeding. Studieshave shown that monthly visits do not disturb the animals unduly, but more frequent visitsare not recommended. Any new(pink) nestlings present in a nestbox should be counted and leftundisturbed. If necessary, theycan be weighed as a batch and the average nestling weightcalculated. Nestling weights can be used to estimate theirapproximate age (see Figure 12).Unlike some mammals, dormicedo not eat or desert their young,provided that disturbance is notexcessive. Nevertheless, youshould avoid disturbing youngfamilies unless detailed studiesare being made of breedingbiology.

Female

Male

Figure 11 Sexing dormice. This canbe more difficult than for othersmall rodents, particularly withyoung dormice. The difference tolook for is the distance between theanus and genital papilla(penis/vagina) which is longer inmales than females. In males, thetestes may be apparent in thebreeding season, but they are notvery prominent.

30

Inspecting nest boxes requires alicence from English Nature or theCountryside Council for Wales(CCW) where dormice are knownto be present. All data fromschemes using 50 or more nestboxes should be submitted to the National DormouseMonitoring Programme,administered by the People’s Trust for Endangered Species.

3.5 Marking dormice andtaking samples