the Digestive Tract - Carolina Curriculum

Transcript of the Digestive Tract - Carolina Curriculum

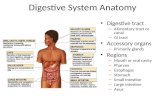

OVERVIEWIn Lesson 1, students discussed what they knowabout human body systems and the majororgans of the body. In this lesson, they focus onthe digestive system. They explore how foodmoves through the digestive tract by means ofperistalsis. This inquiry provides a foundationfor the next five lessons, in which students willinvestigate what happens to food as it movesthrough the mouth, esophagus, stomach, smallintestine, and large intestine.

BACKGROUNDThe purpose of digestion is to break foods downinto a form that can be absorbed into the blood-stream and transported to the cells of the body.Digestion is not a single activity but a series ofprocesses. These processes can be mechanicalor chemical.

• Mechanical digestive processes include thetearing and grinding action of the teeth, themixing and mashing action of the tongue, thechurning of food by the muscles that line thewalls of the digestive tract, and the breakingdown of large fat droplets into smaller onesthrough the action of bile.

• Chemical digestive processes are a seriesof actions whose purpose is to break downthe chemical bonds in nutrients so that they can be absorbed into the bloodstream.Chemical digestion is accomplished by thedigestive enzymes.

The distinction between mechanical andchemical digestion is not always clear-cut. Youmay simply tell students that mechanical diges-tion prepares food for the more complex processof chemical digestion.

2Moving Throughthe Digestive Tract

STUDENT OBJECTIVES Discuss the purpose ofthe digestive processes.

Build a model of thedigestive tract.

Explore how food movesthrough the digestive tract.

Explore the function ofmucus in the digestivetract.

Inquiries 1Periods 2

CONCEPTS Food passes through thedigestive system by theprocess of peristalsis.

Food must be brokendown mechanically andchemically before it can pass into thebloodstream and bedelivered to the cells.

The digestive tract islined with mucus, aslippery secretion thathelps food pass throughthe system and protectsthe inner walls of thedigestive tract.

LESSON

STC/MS™ HU M A N BO D Y SY S T E M S 11

SAMPLE

12 STC/MS™ HU M A N BO D Y SY S T E M S

LESSON 2 MO V I N G TH R O U G H T H E DI G E S T I V E TR A C T

The human digestivetract (see Figure 2.1) is a single, convoluted tubethat is about 8 to 10meters (m) long. Its wallsare composed of an innerlayer of circular musclethat is surrounded by alayer of longitudinal muscle.(The stomach has a thirdlayer composed of diagonalmuscle.) These muscularlayers are held togetherby connective tissue andare covered and protectedby epithelial tissue.

The circular and longi-tudinal layers of musclework together to producewavelike motions thatpush food slowly throughthe digestive tract andhelp break it down intosmaller and smaller parti-cles. This wavelike motion iscalled peristalsis. Althoughthe force of gravity has aminor role in the passage offood through the digestive tract,peristalsis provides the major push.The peristaltic contractions are sostrong that food would even continueto move forward through your digestivetract if you were standing on your head!

Another muscular activity that is essential to digestion is provided by the sphincters.These rings of thickened muscles facilitate thepassage of food from one area of the digestivetract to another. They usually ensure that foodcontinues to move in one direction. Sphinctermuscles are found at the openings of the diges-tive system, that is, at the lips and anus. Othersphincter muscles are located at points wheretwo digestive organs meet (for example,between the esophagus and the stomach).

Food enters mouth

Pharynx (back of mouth) Esophagus. The journey from

the mouth to the stomachtakes approximately 6 seconds.

Within 2 hours, the pyloricsphincter opens to releasechyme, a little at a time,into the small intestine.

The stomach fills as food isswallowed. Food may remain inthe stomach up to 41⁄2 hours.

Within 4 to 12 hours, digestednutrients are being absorbedinto the bloodstream.

Within 18 hours,excess water passesback into the blood-stream, leaving solidwaste (feces).

Appendix

The solid waste usuallytakes between 12 and 24hours to move through thelarge intestine and to beeliminated through the anus.

Figure 2.1 Simplified illustration of the human digestive

tract and the digestive processes

SAMPLE

STC/MS™ HU M A N BO D Y SY S T E M S 13

LESSON 2 MO V I N G TH R O U G H T H E DI G E S T I V E TR A C T

Several accessory organs (see Figure 2.3),including the liver, pancreas, and gall bladder,complement the organs of the digestive tract.The salivary glands, located in the mouth, arealso accessory organs of digestion. Althoughstudents will not study these organs throughinquiry in this module, they will read aboutthem and learn about their role in digestion.

By the time food substances reach the largeintestine, digestion and absorption of nutrientshave already been completed. All that remains is undigested waste. When these waste materialsenter the large intestine, they contain a largeamount of water and electrolytes (watery solu-tions of acids, bases, or salts). The major activity that takes place in the large intestine is the absorption of water and electrolytes intothe bloodstream.

The sphincters control the passage of foodfrom one area to another. For example, thepyloric sphincter (see Figure 2.2) helps regulatethe passage of food into the small intestine.

Mucus, a slippery secretion that coats theinner walls of the digestive tract, also facilitatesthe movement of food. In addition, mucus pro-tects the stomach and small intestine frombeing damaged by acidic gastric juices andother digestive enzymes.

Most digestive activity occurs in the duode-num, the first 25 centimeters (cm) of the smallintestine. The entire small intestine is about 6 to 8 m long. Many complaints about stom-achaches, as well as the digestive noises wecommonly refer to as “stomach growling,” areactually the result of discomfort or movementin the small intestine.

Figure 2.2 The stomach has three layers of

muscle: longitudinal, circular, and diagonal.

The inset at the left shows a transverse

view of the pyloric sphincter.

Pyloricsphincter

Esophagus

Outer layer of longitudinal muscles

Middle layer ofcircular muscles

Inner layer ofdiagonal muscles

Duodenum

SAMPLE

14 STC/MS™ HU M A N BO D Y SY S T E M S

LESSON 2 MO V I N G TH R O U G H T H E DI G E S T I V E TR A C T

been dispatched to planet Earth by scientists in another galaxy. The spies’ job is to learn as much as they can about human anatomy and physiology.

Peppi and Bollo can shrink or expand in sizeat will, and they take advantage of this remark-able trait to enter the body of a human. Duringtheir journey, they discuss what they see; Peppiis the teacher and Bollo is an eager learner.

Episodes of “Spies” appear periodicallythroughout this module. The story reinforcesand supplements many of the concepts yourstudents will investigate and discuss in class.Please help students understand that althoughthe story reads like science fiction, the infor-mation it presents about the human body isbased on facts.

As more water is absorbed, the undigestedwaste in the large intestine becomes more concentrated. Dead bacteria make up aboutone-third of these semisolid remains, or feces.Other living bacteria feed on the undigestedwastes and often produce intestinal gases,called flatus. The feces remain in the rectumuntil they are eliminated through the anus.

In this lesson, students simulate the peri-staltic action of the digestive tract by moving an oiled tennis ball through a 10-m plastic tube.The oil on the tennis ball simulates the effect of the mucus.

At the end of Lesson 2 in the Student Guideis a reading selection entitled “Spies: AllSystems Go!” This is the first episode of a serialreader that recounts the adventures of Peppiand Bollo, two imaginary creatures who have

Figure 2.3 The accessory organs of digestion

Liver

Gall bladder

Duodenum

Common bile duct andpancreatic duct emptyinto the duodenum.

Esophagus

Pancreas

Stomach

Small intestine

SAMPLE

STC/MS™ HU M A N BO D Y SY S T E M S 15

LESSON 2 MO V I N G TH R O U G H T H E DI G E S T I V E TR A C T

probably not plan any administrative tasks dur-ing this lesson. If your class period is 45 to 50minutes long, decide on a cutoff point for thefirst half of the inquiry. For example, you mayfind that students will be able to complete thebrainstorming and to mark their plastic tubingduring a 45- or 50-minute class.

Getting Started

1. Direct students’ attention to the questionsyou have recorded on newsprint. Tell stu-dents to take a few minutes to brainstormanswers to these questions. They shouldrecord their answers on a new page in theirscience notebooks.

2. Ask a spokesperson from each group toshare the group’s responses with the class.Record all answers on newsprint. The classwill take a second look at these questionsat the end of the lesson.

Inquiry 2.1Moving Right Along

PROCEDURE

1. Ask students to follow along as youreview the Procedure for this inquiry inthe Student Guide. Emphasize the following points:

A. The numbers in Table 2.1 of their guideindicate the length of each organ, notthe cumulative length of the organs. For example, the esophagus is 25 cm long and the stomach is 22 cm long. Studentsshould place the first mark 11 cm from the opening of the tube. Using that mark as a starting point, they should then measure 25 cm and make a second mark

MATERIALS FOR LESSON 2

For the teacher1 trash bag (large) 1 container of vegetable oil2 pieces of newsprint or transparencies*1 black marker

For each group of 4 students1 plastic box with lid1 polyvinyl tubing, 9.3 m 1 pair of scissors1 black marker1 tennis ball (soaked in vegetable oil and

placed in a small plastic storage bag withfold-and-close top)

1 plastic storage bag with fold-and-close top1 measuring tape, 150 cm 1 plastic resealable storage bag, large,

22.9 × 30.5 cm (9″ × 12″)

*Needed, but not supplied

PREPARATION

1. Prepare a transparency of Figure 2.2 in theStudent Guide (SG). The figure depictshow to mark the plastic tube.

2. Write the following questions on newsprint.Leave space under each question to enterstudents’ responses.

A. How do you think food moves through thedigestive tract?

B. What do you think happens to food as itmoves along the digestive tract?

C. Why do you think the digestive tract getsnarrower at some places?

NOTE This inquiry takes about 90 minutes tocomplete. Regardless of whether your studentswill complete it in one 90-minute period or two45- to 50-minute class periods, you should

SAMPLE

the questions in Procedure Step 7 as they proceed.

NOTE Consider displaying one of the tubes on awall in your classroom. Encourage students torefer to it as they progress through this part ofthe module. Make sure the organs are clearlylabeled. The opportunity to see the tube givesstudents an appreciation of the length of thedigestive tract.

REFLECTIONS

1. Discuss the answers to the two sets ofquestions that appear in “Getting Started”and Procedure Step 7 of the Student Guide.

SG “Getting Started”A. How do you think food moves throughthe digestive tract? (Food moves throughthe digestive tract by the squeezing actionof circular and longitudinal muscles.Students may suggest that they simulatedthis squeezing action because their handssqueezed not only down the tube but alsoaround it.)

B. What do you think happens to food as it moves through the digestive tract?(The food is broken down into smallerand smaller particles. The breakdown iscaused by digestive juices as well as bythe squeezing action of the muscles.)

C. Why do you think the digestive tractgets narrower at some places? (Thesenarrow places are called sphincters. Theyare muscles that control the passage offood through the digestive system. Theyalso help make sure that food movesthrough the system in only one direction.Sphincter muscles are found betweenorgans. They are also found at the twoopenings of the digestive tract, the lipsand the anus.)

for “Esophagus.” Beginning at the markthey have made for the esophagus, theyshould then move on to “Stomach.” Theyshould continue this process until theyhave made the mark for the end of therectum.

B. When putting the ball in the tube, stu-dents should not touch the ball directlywith their fingers. They should manipulatethe ball through the bag. If their fingersget greasy, they will find it very hard tosqueeze the ball through the tube.

C. Students should keep the tube horizontalat all times.

D. Each student in a group of four shouldsqueeze the ball through approximately 2 m of the tube. This will give everyonean opportunity to participate.

E. The student at the far end of the tubeshould have a plastic bag into which tosqueeze the ball.

2. Explain the cleanup procedures.

A. At the end of a 45- or 50-minute class,have students put the tubing in the largeplastic storage bag. Have them write theirnames on the bag with the marker, givethe bag to you, and return their plasticboxes to the materials center.

B. At the end of the inquiry, have studentsdispose of the plastic tubing in the largetrash bag and return their other suppliesto the materials center.

3. Have a volunteer from each group pick upmaterials for the inquiry.

4. Have students start the inquiry, begin-ning with Step 2 in the Procedure of theStudent Guide. Remind them to discuss

16 STC/MS™ HU M A N BO D Y SY S T E M S

LESSON 2 MO V I N G TH R O U G H T H E DI G E S T I V E TR A C T

SAMPLE

STC/MS™ HU M A N BO D Y SY S T E M S 17

LESSON 2 MO V I N G TH R O U G H T H E DI G E S T I V E TR A C T

comes from the Greek words osein(meaning “to be going to carry”) andphagein (meaning “to eat”). Then havethem try to find other words in Englishthat contain the root words.

■ Science

2. Have students find out why snakes caningest and swallow objects whose diametergreatly exceeds their own. Have theminclude images where possible.

■ Health ■ Science

3. Ask students to research how laxativesand antidiarrhetics work.

■ Science

4. Ask students to devise a means of addingsimulated sphincters to the model of thedigestive tube that they used duringInquiry 2.1. What common household oroffice objects could they use to narrowthe passages between organs?

ASSESSMENTBecause this is an introductory lesson, it is recommended that you grade students on thebasis of how well they contributed to the classdiscussion, how they cooperated in theirgroups, and how much effort they made toanswer the written questions.

PREPARATION FOR LESSON 3Directions for preparing and distributingchemicals may be found in the materials kit.Check the Materials List and Preparation sec-tion for Lesson 3 and prepare the containers offoods and chemicals you will need. Label anycontainers that are not already marked.

SG Procedure Step 7A. What does the tennis ball represent?(The tennis ball represents swallowedfood.)

B. Why do you think the tennis ball wassoaked in oil? (The vegetable oil simulatesmucus, a slippery substance that coats thelining of the walls of the digestive tract.Mucus permits food to move more easilyand protects the lining of the digestivetract from the digestive enzymes.)

2. Ask students how the tennis ball is differ-ent from food as it moves through thedigestive tract. (The ball stays the samesize. Food particles would get smaller, andtheir chemical composition would change.)

3. Ask students to think about what theywould like to learn about digestiveprocesses, the organs of digestion, andfood and nutrition. Have them write thequestions in their science notebooks.Note that you will revisit the lists at theend of this part of the module.

HOMEWORK

Period 1Ask students to read “Spies: All Systems Go!”at the end of Lesson 2 in the Student Guide.

Period 2Ask students to read the first section of“Nutrients: You Just Can’t Live Without ’Em,”on page 20 in Lesson 3 of the Student Guide.

EXTENSIONS

■ Language Arts

1. Have students research the derivations and meanings of the names of the digestiveorgans. For example, the word “esophagus”

SAMPLE