The decision to extract: Part 1 - Interclinician agreement...Angle referred to extraction only as "a...

Transcript of The decision to extract: Part 1 - Interclinician agreement...Angle referred to extraction only as "a...

The decis ion to extract: P a r t 1 - In te rc l in ic ian agreement

Sheldon Baumrind, DDS, MS, ~ Edward L. Korn, PhD, b Robert L. Boyd, DDS, MEd, c and Raymond Maxwell, DDS d San Francisco, Calif., and Bethesda, Aid.

As part of an ongoing prospective clinical trial of conventional orthodontic treatment, the decision making patterns of a representative group of orthodontic clinicians were examined. Data were available for 148 subjects (100 adolescents and 48 adults) who had presented at the University of California San Francisco Graduate Orthodontic Clinic requesting treatment for correction of a Class I or Class II malocclusion. The records for each subject were evaluated independently by each of five members of the clinical faculty, making available a total of 740 independent patient evaluations. With regard to the primary decision as to whether extraction or nonextraction treatment was to be preferred, agreement among clinicians was higher than had been anticipated. In almost two thirds of the cases, the decisions of all five clinicians were in agreement as to whether extraction or nonextraction was the preferred treatment modality. (This figure included 59 cases of complete agreement for extraction therapy (40%) and 38 cases of complete agreement for nonextraction therapy (26%)). In only 51 cases (34%), did the reviewing clinicians disagree as to whether extraction or nonextraction was the preferred modality of treatment. The clinicians were also asked to indicate their opinions as to whether orthognatic surgery was likely to be a part of the ultimate treatment course for each individual subject. Nine percent of the 740 patient evaluations contained a clinician judgement that surgery would be a probable or definite component of the orthodontic treatment plan. For 29% of the adult subjects (14 cases) and 23% of the adolescent subjects (23 cases), one or more of the five examining clinicians believed that adjunctive surgical intervention would probably or definitely be appropriate. These high values were unexpected, particularly because the sample had been prescreened by a single clinician to exclude subjects who might require orthognathic surgery. Clinician agreement of Angle classification was also evaluated. Disagreements were observed in 14 adult subjects (29%) and 27 adolescent subjects (27%). Little association was observed between clinician agreement on Angle classification and clinician agreement on whether or not to extract. (AM J ORTHOD DENTOFAC ORTHOP 1996;109:297-309.)

W i t h the possible exception of the deci- sion whether or not to treat, the most crucial decision in the delivery of routine orthodontic care is whether to extract in the permanent dentition. Clinician attitudes concerning extraction have dif- fered in different historical periods. The relatively promiscuous extraction practices of the late 19th century "tooth regulators," dictated largely by tech- nique limitations, 1 gave way in the first third of the present century to the extraction-aversive strategies of Angle and his associates) '3 Although more

Supported by NIDR-NIH grant no. DE08713. aProfessor, Growth and Development, Radiology and Orthopedic Sur- gery, University of California, San Francisco. UMathematical Statistician, Biometric Research Branch, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, Md. CAssociate Professor and Chair, Division of Orthodontics, Department of Growth and Development, University of California, San Francisco. dResident in Orthodontics, Division of Orthodontics, Department of Growth and Development, University of California, San Francisco. Copyright © 1996 by the American Association of Orthodontists. 0889-5406/96/$5.00 + 0 8/1/50010

modulated positions continued to be held by Case 4 and others, by 1930 extraction in the permanent dentition was so anathematized among the parti- sans of the dominant Angle school as to become all but unmentionable. Thus, in the forward of Strang's Textbook of Orthodontia, 5 Anna Hopkins Angle referred to extraction only as "a certain mooted procedure" and elsewhere during this his- torical period, the literature frequently described tooth extraction euphemistically as "reduction in the total number of dental units."

The publications of Grieve 6'7 and Tweed 8'9 dra- matically reversed the predominant thinking of American orthodontics in the mid 1940s. Extrac- tions in the permanent dentition rapidly became the most common treatment strategy for the cor- rection of Class I and Class II malocclusions and, as Brodie remarked ruefully, "soon the air was filled with bicuspids."10 In the period since 1960, two major positive factors and one negative one

297

298 Baumr ind et al. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics March 1996

have tended to shift the balance toward more conservative strategies. The positive factors are (1) improved apparatus for modulating the expression of each patient 's inherent growth potential during childhood and adolescence through the use of extraoral traction and functional appliances, 11-22 and (2) the development of satisfactory techniques for attaching brackets directly to the teeth, 2325 thus avoiding the mechanical increase in dental arch length formerly associated with the interproximal interposition of several thicknesses of band mate- rial. The negative factor that has also helped shift the balance away from extraction therapy during the past decade has been increased fear of mal- practice litigation on the part of practitioners. Dur- ing that period, severe pressures originating outside the specialty have caused many excellent clinicians to become guarded in their t reatment plans and have lead to the development of a new subindustry called "risk management . 26-28 It seems unlikely that such pressures have overall beneficial effects to the public.

Notwithstanding historical debates 4'7'9"z9-32 and current risk containment concerns over the issue of orthodontic extraction, there has thus far been little rigorous investigation of the manner in which clinicians actually make the decision of whether to extract or not. This article reports on patterns of agreement observed among one group of skilled clinicians in deciding whether or not to extract in the permanent dentition for a representative group of adolescent and adult patients. Subsequent pub- lications will report on the reasons given by the clinicians for their decisions and on the associa- tions between the clinicians' decisions and sets of objective measurements made on cephalograms, study casts, and facial photographs. The data are taken from the records of the UCSF arm of a joint prospective study now in progress at that institution and the University of the Pacific School of Den- tistry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All subjects who were considered for treatment at the Graduate Orthodontic Clinic of the Department of Growth and Development at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) between Oct. 15, 1989, and Oct. 15, 1991, were evaluated for inclusion in a longitudinal prospective study investigating the effects of extraction in the routine orthodontic treatment of adolescent and adult subjects. Potential subjects were evaluated after preliminary consultation and records taking by a team consisting of a clinical instructor and a second-year

orthodontic resident. All patients who met the protocol criteria were offered the opportunity to participate in the study. Preliminary eligibility criteria for inclusion in the sample were (1) presence of a Class 1 or Class II malocclusion that would benefit from full orthodontic treatment but for which partial treatment or orthog- nathic surgical intervention were considered inappropri- ate; (2) age appropriateness, i.e., more than 20 years of age for patients in the adult cohort and between 10 and 15 years of age for patients in the adolescent cohort. (Here the term adolescent is used in a somewhat idiosyn- cratic sense to include all subjects for whom growth is an important factor in treatment planning with the excep- tion of those for whom development was insufficiently advanced for it to be ethical to ask a clinician to make a decision whether or not to extract.) (3) Presence of a normal complement of permanent teeth in or nearing eruption; (4) normal health as evidenced by the absence of chronic illness; and (5) no history of prior orthodontic treatment.

Random assignment of "borderline patients" to ex- traction or to nonextraction treatment was an important part of the study protocol. For this purpose, it was necessary to define the concept of borderline in opera- tional terms. For purposes of the study, we defined a borderline patient as one for whom different skilled orth- odontists, when given the opportunity to examine the clinical records independently, disagreed as to whether extraction or nonextraction therapy was the optimum treatment. The protocol, which has been reported else- where, 33 also stipulated that each patient would be treated at a university clinic under the supervision of a clinical instructor who concurred with the course of treatment to which the subject had been randomized.

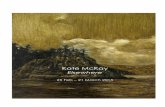

Before defining the treatment plan for each subject, the protocol was explained to each potential subject and informed consent was obtained. Then, all records (in- cluding head films, dental x-ray films, study casts, facial and intraoral photographs, cephalometric tracings, and all written chart materials) were examined independently by each of five orthodontic specialists who were members of a larger pool of clinical instructors. Each instructor recorded his treatment preferences and the reasons for them on a separate "Clinician's Case Analysis Form." The design of this form underwent some modifications early in the study but had reached a definitive state by its sixth month. (See Fig. 1.)

Each clinician made his examinations separately and without consultation with the other clinicians, thus yield- ing an independent judgment as to whether extraction or nonextraction treatment was preferable in each indi- vidual case. By analyzing the five such independent judgements available for each case, we could evaluate empirically the between-clinician concordance or discor- dance in the decision making process. Note that this approach measures the clinicians' actual decision making performance under clinical conditions. We consider this approach to be superior to the alternative method of

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Baurnr ind et al. 299 Volume 109, No. 3

~ r , brre Patient# _L _J_/~:?~ !) - Date __

Adult Adolescent (Youth)

P,e~en~s Narm ~.~ o '~,~) s,~nn~ F~,~ ~ ._ I. .,

Deparlment of Growth and Development Graduate Orthodontic Clinic - Prospective Odhodontic Study

DE#08713

Form 0004.1 4/4/90

CLINICIAN'S CASE ANALYSIS FORM

I Please review the record for this patient and answer the following questions. Please do not discuss this patient with the other case evatuators until all evaluators have cornpleled their independent reviews.

1. The patient's Angle classification patient is:

[ ] ck~ss,.t [ ] ~ ~a't, [ ] Class 1[.2

2. I believe this patient would be best treated with a plan that:

[ ] Includes extractions other than third molars.

Please indicate probable preferred extraction pattern:

D, her(, ,cats, t

~ D o e s ~ include extractions (except possilby third molars).

Please estimate the likelihood that extraction may be incQcated later.

~ High/y Improbable

[ ] Possible but not probable

[ ] Quite possible (mare than 3 chances in 1 O)

3. Treatment for this patient:

[ ] Should inlcude odhognathic surgery. [ ] Should not inlcude odhognathic surgery.

6. My decision to extract or not extract is based on the following considerations in approximate order of tmpodanc.e:

bl ~ - J ~ J r 0 J

(Please seal this form Into the accompanying envelope before returning It to the resident.)

Fig, 1, Clinician's case analysis form.

examining written or verbal statements in which clini- cians summarize their theoretical positions in general.

In November 1991 the evaluation of the intake infor- mation for the subjects already enrolled in the UCSF sample was commenced. In this article, we report enu- merative data and statistics on the clinician's decisions for the 148 subjects who had been enrolled by that date.

R E S U L T S

Seven hundred and forty discrete clinical treat- ment decisions are reflected in the raw records of this study. A number of previously unquantifiable issues concerning decision making in orthodontic treatment can be addressed with this information. In this section, we first outline the characteristics of both the sample and the panel of examining cli- nicians. Then we report our principal findings on a case-by-case basis with respect to four issues: (1) between-clinician agreement concerning the

primary decision to extract or not to ext ract / (2) between-clinician agreement concerning extraction pattern (i.e., which teeth the clinicians believed should be removed when they deemed extraction to be indicated), (3) the incidence of recommendations for collateral surgical intervention, (4) the incidence of between-clinician disagreement on Angle classifi- cation.

Characterist ics of the sample

To recruit a representative sample of subjects, all patients for whom orthodontic records were taken at the two CSF clinics during the recruitment period were evaluated for inclusion in the sample. Initially, 1323 records were gathered, of which 252 appeared to have met the screening criteria for inclusion. On further examination, two sets of rec- ords were found to have been duplicated. Removal

300 Baumrind eta[. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics March 1996

Table I. R e c r u i t m e n t o f the e x p e r i m e n t a l s a m p l e

Subtotal I Totals % of Subjects

A. Summary Number of subjects available for 1323 a

assessment Number of subjects acceptable 252 Number of subjects declined to 82 b

participate Number of subjects lost to logistical 22 c

problems Number of subjects included in 148

sample Number of subjects not considered 1069

acceptable

B. Distribution of reasons for nonrecruit- ment of 1062" potential subjects 1. Age inappropriate

a. Less than 10 years old 227 b. Between 14 and 20 years old 316 c. Other 1 ~ 544

2. Insufficient eruption of permanent 228 teeth

3. Missing or extracted permanent 120 teeth

4, Adjunctive surgery considered likely 92 5. Limited treatment

a. Single phase of a two phase 26 treatment

b. Required partial treatment only 24 c. Retention, retreatment or 18

observation d. Transfer in 12 80

6. Not treated 42 7. Miscellaneous other

a. Transferred to craniofacial 9 b. Transferred to other orthodontist 5 c. Unrepresentative treatment risk 6

(perio problem or short roots) d. Could not understand consent 1 21

form (language problem)

C. Total number of reasons 1127

51% 21%

11%

9%

6% 4%

2%

106%**

*No reasons are available for seven potential subjects. **More than one reason for exclusion was cited for nonrecruitment of some potential subjects. Explanations for Table I changes: a. 1325 less two duplicate records. b. Approximately half these subjects declined to consider an extraction alternative under any circumstances. c. Includes otherwise acceptable subjects for whom it was impossible to obtain five independent clinical assessments in a timely manner. d. Includes one otherwise acceptable subject aged 62.5. This patient was deleted post hoc because she was more than 20 years older than any other subject in the selected sample.

of t he dup l i ca t e s y i e l d ed a f inal ros te r of 250 sub- jects , o f w h o m 82 d e c l i n e d to p a r t i c i p a t e a n d 20 w e r e d r o p p e d b e c a u s e of diff icul ty in o b t a i n i n g five i n d e p e n d e n t e v a l u a t i o n s of the i r r eco rds w i t h i n a r e a s o n a b l e t i m e f r ame . T h u s the f inal s a m p l e con- t a i n e d 148 subjects . T h e r e a s o n s for t h e exc lus ion f rom the s a m p l e o f t h e r e m a i n i n g 1173 p o t e n t i a l

sub jec t s a re l i s ted in T a b l e I. ( T h e p r o p o r t i o n of subjec ts dec l i n ing to p a r t i c i p a t e was c o n s e q u e n t i a l (33%), t e n d i n g to con f i rm the p r e d i c t i o n by P a q u e t t e , J o h n s t o n e t a l ? 4 t ha t diff icul ty w o u l d b e e n c o u n t e r e d in r e c r u i t i n g i n f o r m e d subjec ts in to a p rospec t ive s tudy of o r t h o d o n t i c t r e a t m e n t . T h e ma jo r i ty of the subjec ts who d e c l i n e d to b e r an -

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Baumr ind et al. 301 Volume 109, No. 3

Table I I . Demographics of the full sample

Adolescent cohort Adult cohort (Age < 15 years) (Age > 20 years)

A. Age at presentation (Mean _+ SD) Males 12.8 _+ 1.2 28.6 _+ Females 12.5 +- 1.2 26.8 _+

All 12.6 _+ 1.2 27.6 -4- B. Distribution by sex

Males 44 22 Females 56 26

TOTALS 100 48

C. Distribution by ethnicity White 25 20 Hispanic 40 10 Black 13 6 Asian 16 9 Middle Eastern 6 2 Native American 0 1

TOTALS 100 48 D. Distribution by angle class*

Class I 63 31 Class II, Division 1 35 13 Class !I, Division 2 2 4

TOTALS 100 48

Totals

5.0 6.2 5.7

66 82

148

45 50 19 25 8 1

148

94 48 6

148

*As designed by the majority of the judges. Subdivisions and tendencies have been pooled with major categories. **Pooling inappropriate.

domized to t rea tment indicated that they would not accept extraction therapy under any conditions. We believe our relative success in building an accept- able sample size in the presence of subject bias was based on our ability to demonstrate to most sub- jects that no subject would be randomized without objective evidence that there was true uncertainty as to which t reatment was preferable in his or her particular case.)

Demographics for the 148 subjects included in the sample are summarized in Table II. Approxi- mately a third of the subjects in the sample are adult, somewhat more than half are female, and Class I malocclusions outnumber Class I I malocclusions by a count of 94 to 54. These ratios are fairly similar to corresponding values reported in other contempo- rary orthodontic surveys. 35-37 The proport ional mix among different ethnic groups differed between the adolescent and adult cohorts to a degree that was marginally significant (p < 0.10, Fisher 's exact test 38 for 6 x 2 table). Nonblack subjects of Hispanic ori- gin constituted two fifths of the adolescent cohort but only a fifth of the adult cohort. The high repre- sentation of growing Hispanic subjects probably re- flects recent shifts in population pat tern in Califor- nia and almost certainly would not have been seen had this study been per formed 10 years ago.

Characteristics of the clinician panel

In addition to choosing an appropriate sample of subjects, we a t tempted to obtain a set of clini- cians representative of the clinical specialists to whom we expect the results to generalize. To satisfy the design requirement of having five independent evaluations for each subject, it was necessary at UCSF to involve a total of 14 members of the clinical teaching staff. The credentials of these clinicians (who did not include any of the authors) are summarized in Table III . Like the great major- ity of clinicians who trained in their age cohorts, all were male. In terms of ethnic background, 10 are whites of European extraction, 2 are of A s i a n parentage, 1 is black, and 1 was born in Africa of parents who came from India. Although clinicians who received their specialty education at UCSF are overrepresented, we believe that these 14 clinicians reflect quite well the distribution of education and experience of contemporary university-trained orthodontic specialists whose primary commitment is to clinical practice.

PRINCIPAL FINDINGS

Findings, with respect to the four issues previ- ously enumerated, are summarized separately for

302 Baumr ind et al. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics March 1996

Table III. Characteristics of the judges

Judge Years in no. Specialty training at orthodontic practice

1 USC 2 UCSF 3 UCSF 4 UCSF 5 UCSF 6 U Oklahoma 7 UCSF 8 Royal Dental Col-

lege/Copenhagen 9 UCSF

10 UCSF 11 UCSF 12 UCSF 13 UCSF 14 UCSF

Years as Board eligible clinical instructor or certified

29 25 C 7 6 E

28 27 C 5 4 E 8 5 C 5 5 C 8 7 C

23 23 C

33 13 C 19 19 C 33 30 C 44 44 C 12 10 C 4 2 E

USC, University of Southern California. UCSF, University of California San Francisco.

adolescents and adults in Table IV. Each row displays data for a single case. The 148 cases in the sample have been regrouped and renumbered in terms of the level of judge agreement with respect to the primary decision of whether to treat by extraction or not.

The columns of Table IV are grouped into sections, each dealing with one of the four principal issues. Referenced to the data in the table, we now consider those issues in order.

Distribution of nonextracUon and extraction decisions (Table IV, section 1)

The observed distribution of nonextraction and extraction decisions is summarized in Table IVA and IVB. The data reveal a strong tendency toward consensus among the clinicians with regard to the central decision of whether or not to extract. It may be seen in the table that for approximately two thirds of the subjects in each cohort, all five exam- ining clinicians arrived independently at the same decision as to whether extraction or nonextraction was the bet ter treatment strategy. Unanimous agreement among five clinicians, occurred in 97 cases of 148 (66%), whereas 3:2 or 2:3 splits occurred in only 26 (18%). (In the adult cohort, unanimous decisions for extraction were more than twice as common as those for nonextraction. Within the adolescent cohort, the corresponding ratio was closer to four to three.) This strong consensus was frankly unexpected by at least one of the authors (S.B.), although some other orthodon- tists may be less surprised.

Agreement on extraction pattern (Table IV, section 2)

When the clinicians agreed to extract, they also tended to agree strongly on extraction pattern (i.e., which teeth should be removed). The most common patterns of extraction were four premolars, two pre- molars, three premolars, and one lower inciser. These patterns accounted for all but 37 of the 433 extraction decisions. Incidences for the four most common patterns are arranged in subcolumns in section 2 of Table IV. Incidences of the 37 other patterns are specified in Table IV, section 1. All five clinicians specified the same extraction pattern for 12 of the 23 adult subjects for whom they agreed to extract (Table IVB, 3). In 8 of these 12 cases, all five clinicians advocated the removal of four premolars. Of itself, this finding may not seem too surprising, given that this is the most common extraction pat- tern and that, for the present purposes, all combina- tions of first and second premolar removal were grouped together. But the fact that all five clinicians also independently proposed removing premolars in Case 134, three premolars in Case 135, and one lower incisor in Cases 136 and 137 does seem re- markable. For the remaining 11 adult subjects unanimously designated for extraction, four of five clinicians agreed on extraction pattern in six cases and three of five clinicians agreed in four cases. In only one case (Case 148) did fewer than three clini- cians agree on a common pattern.

Clinician consensus on extraction pattern for the analogous agreement group in the adolescent cohort may be examined in Table IVA, 3. For the 36 sub-

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Baumrind et aL 303 Volume 109, No. 3

Table IVA. Clinician decisions on extraction: full sample (distribution of clinician assessments by case)

A D O L E S C E N T C O H O R T N = 100

304 Baumr ind et al. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics March 1996

Table IVB. Extraction decisions: Distribution of clinician assessments

CASE #

lOl 102 103 104- 105 106 107 1(~. 1110 110 111 112 113 114, 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 125 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134- 135 1::)6 137 138 139 140 14-1 14.2 143 144 14.5 146 147 148

A D U L T C O H O R T (N - -48 )

SECTION 1 SECTION 2 SECTION:3 Ext vs Non-Ext DECISIONS Extraction PATTERN SURGERY

Decision Ratle~ DIstribution of Extraction PA'I'rERN6

NONLX TO EXT 4 bi 2 bi 3 bi 1 inc Other Probable Definite

1. AGR£EMENT NOT TO 5 t o o

EXTRACT

N = 1 0

4 tO1 N:=I 1 4

l t o 4 4 4

N = 5 -2 - - 2. DIS- 2

AGREEMENT 2 3 t o 2 2

N = 1 5 2 N = 6 2

3 2 to 3 N--3

3. AGREEMENT TO 0 tO 5

EXTRACT

N = 2 3

5 5

4

1

2

1

4 1 1 4 1 1 4 1 1 4 1

4 4

3 1 2 3 1 1 3 1 1 1 3 2 1 1

SECTION 4 ANQLE CLASS

Agreement Dis-Agreement

3 2 1 5 1 5 1 5

4 1 1 5

4 1 1 5

1 4 2.1 4 2.2 5 1 4 1 4

2.2 5 4 1 r 1 3; 1

1 5 4 1

1 5 3 2 4

1 4 1 5 1 5 1 5 1 5

1 4 1 5 1 5 1 5 1 5 1 5

2.1 4 2.1 4 2.1 4 1 5

3 Not Available

4 1 3 2 2 3

1 4 1 5 1 5

2.1 4 Not Available

t 1 , 2 3

TOTALS A. 204 33 23 3

TOTAL8 B. 79 29 22 12

TOTALS A+B 283 6Q 4,5 15

# For the purposes of this article, all Cases have been renumbered sequentially.

12 21 12 72 28

15 8 22 29 19

37 29 34 101 47

jects in this group, all five clinicians suggested the same extraction pattern in 21 cases, four clinicians of five concurred in six cases, and three of five agreed in seven cases. In only two cases (Cases 99 and 100) did fewer than three clinicians agree on a common ex- traction pattern.

Among the 59 subjects for whom five clinicians agreed unanimously on extraction in the adolescent and adult groups taken together, more than two alternative extraction patterns were suggested in only nine cases (Cases 97 through 100 in the adolescent cohort and Cases 144 through 148 in the adult cohort).

Decisions on surgery (Table IV, section 3)

Despite the fact that the subjects in the sample had been preselected at preliminary consultation on the basis that they were not candidates for orthognathic surgery, the examining clinicians con- cluded that such an outcome was at least probable in 9% of the 740 individual clinician decisions. The total of 63 surgery-positive responses (34 "definite" indications plus 29 "probable" indications) was distributed over 37 sub jec t s -14 (29%) in the adult cohort and 23 (23%) in the adolescent cohort. For 16 of these 37 subjects, more than one clinician iden- tified surgical intervention as a probable or definite

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics Baumrind et al. 305 Volume 109, No. 3

Table IVC. Distribution of other extraction solutions

ADOLESCENT COHORT (N=100)

1. Decision 2. Disb'ibution of Extraction Ratios PATTERNS 2'. Distribution of OTHER Extraction PATI'ERNS

CASE# Non-Ext I Ext 4bi 2~i 3hi l i n c i : , ~ : : 46 1 4 3 iiiii:~i i~:: iii;~:~: Extraction: 12attern undefined ' '

~ ~i~i~,il ~n;-;,~p~;~c;;b~ . . . . . . . . " 5247 31 24 1 1 2 ii~;i~i~tiii:~ii::~:~i!iii One upper bicuspid 53 2 3 3 B<ith Non-extraction Voters advised Non-treatment. 62 2 3 2 !iil ii~:...::il One upper bicuspid 87 0 5 4 Two upper fireS bicuspids and both lower cenlrals 88 0 5 4 ~i~:: ~:i~:i:~!::i ::~ Two upper fireS bicuspids and both lower laterals 89 0 5 4 :: ~ ~ i ::i Two upper bicuspids and both lower laterals 90 0 5 4 !:!i!:i~i!iii I: Two.upper bicuspids and both lower laterals 9t 0 5 4 i:!ii!i~iiii~i _Extr_a~i_onp_a_tter_n_t_o~_d_et_er__m_in__ed_Lat_~_ 94 0 S 3 ~i~:~i~i~ Two up_per fires biscu_spids end both lower centrals _~C?.). 98 0 ,5 1 3 ~,~,~,~ E~raction~-oth-erw-iseunspecified

B. ADULT COHORT (N--48)

1. Decision 2. Dislribution of Exl~'action Ratios PA'I-rERNS

CASE# Non-Ext I Ext 4h i 2h i 3bJ fine 115 1 4 2 116 1 4 2

121 3 2 122 3 2 iii~ ::: !

,124 2 a 2 142 0 5 4

43 o 5 4 144 0 5 3 ~ 1 ~ i ~ : ~ 14s o 5 3 1 148 0 5 2 1 ~:i~i~ii~

2'. Distribution of OTHER Extraction PAI-I'ERNS i

Possible ext, pattern not specified (X2) One upper bicuspid and one lower incisor (X2.); The single

:!:! !!i:: :/i!i!! i Non-Xrecomrnendatien was ambiguous One upper bicuspid (X2) One upper bicuspid (X2) Prob ,able ext; precise pattern tO be determined later, Three bicuspids and one upper first molar Ope_ u p p ~ _bj _c _u_spi" d_ _ Two upper bicuspids and both lower canines (sic!) l"_w_o_ upp~ fi_rst bicuspids and one lower centraJ Three bicuspids and one upper molar 0(2)

# For the purposes of this article, all Cases have been ranumbered sequentially.

component of treatment. Between-clinician agree- ment favoring surgery tended to be more common in the adult cohort than in the adolescent cohort. Probable candidates for surgery were identified in the extraction, nonextraction, and disagreement groups of the adolescent cohort and in both the extraction and disagreement groups of the adult cohort.

The relatively large number of adolescent sub- jects, for whom at least one clinician entertained the possibility of adjunctive orthognathic surgery, was surprising to us. These findings were entirely unexpected and warrant further examination. At minimum, they cast doubt on the appropriateness of our action in using a single clinician's opinion concerning a prospective subject's need for ad- junctive orthognathic surgery as a screening cri- terion. It is reasonable to infer that the compo- sition of the group of subjects excluded at initial intake because their examining clinicians consid- ered them to be candidates for surgery (see Table I) was, to a consequential degree, a function of

which patient happened to be examined by which clinician.

D e c i s i o n s o n A n g l e c l a s s i f i c a t i o n

(Table IV, section 4)

As is also documented in Tables IVA and IVB, disagreements among clinicians with regard to Angle classification (which is generally considered to be a relatively straightforward decision) were almost as common as disagreements over the deci- sion to extract. Twenty-eight adolescent subjects and 16 adults subjects were identified for whom the clinicians failed to reach agreement about Angle class. For 22 adolescent patients and 12 adult subjects, there was disagreement as to whether a case was Class I or Class II; for eight adolescent subjects and four adult subjects there was disagree- ment as to whether a Class II case was Division 1 or Division 2; for one adolescent subject there was disagreement as to whether the proper designation was Class I, II, or III. Little association was seen between disagreement on Angle classification and

306 Baurnrind et aL American Journal of Orthodonlics and Dentofacial Orthopedics March 1996

Table V. Extraction/nonextraction decisions. Numbers of cases and numbers of reasons by clinician and cohort

OVERALL: (ALL-CLINICIANS) EXT NON-EXT

Adol.scon t 2rS I =2s I soo Aduq l s e I 8= I =40 Totals 433 307 740

INDIVIDUAL CLINICIANS:

Clinician# COHORT

EXT NON-EXT TOTAL

Clinician 1 -Adolescent Adult

28 8 36

Clinician 2- Adolescent Adult Total 21 16 37

Clinician3-Adolescent I 29 I 2, pc Adult I 13 I 6 I19 Total 42 27 69

,,n,o,ao,-,0o,e con, l, , ,0o,t , 0 'l 00 I'0 Total 1 0 t

Clinician 5 - Adolescent IAdultl 3183 II 281 15264

Total 51 29 8 0

Clinician6-Adolescent I 14 I 22 136 Adult I 7 I z 14 Total 21 29 50

Clinician 7 - Adolescenl 48 Adull 26 Total 40 34 74

Clinician# EXT NON-EXT TOTAL COHORT

Clinician 8- Adolescent I 34 I 27 161 Adult I 22 I 9 p t Total 56 36 92

6 Clinician 9- Adolescent I I 9 115 Adult I 3 I 2 I s Total 9 1 1 20

Clinician 10- Adolescent I 19 I 13 132 Adult I 10 I 4 114 Total 29 17 46

34 59 Clinician 11 - Adolescent I Adult I 18 26 Total 52 33 85

Clinician 12- Adolescent I 29 I 25 [54 Adult I 19 I 12 131 Total 48 37 85

Clinician 13 - Adolescent ! 1 6 I 18 134 Adult I 10 I 8 1 la Total 26 26 52

Clinician 14-Ad°lescent IAdult I 54 ~ ~

Total 9 4 13

disagreement on extraction decision. The percent- age of cases for which disagreement on Angle classification was observed was approximately the same in both the adolescent and the adult cohorts (28% and 32%, respectively).

Individual differences between clinicians regarding the decision to extract

It is of interest to know how similar and how different the clinicians were in their patterns of decision making. (It is generally accepted that some

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics B a u m r i n d et al. 307 Volume 109, No. 3

clinicians tend markedly toward extraction deci- sions, whereas others tend markedly not to extract). Table V therefore examines the decision making patterns of the individual clinicians. Overall, as may be seen by examination of the single table grouping data for all clinicians, extraction decisions outnumbered nonextraction decisions by a ratio of 4: 3. The data of the same table show that clinicians opted for extraction less frequently in the adoles- cent cohort (55%) than in the adult cohort (66%). This difference is significant at the p < 0.01 level (Fisher's exact test for 2 x 2 table). An individual table is also provided for each clinician. By exam- ining the tables for the individual clinicians, we can ascertain that all but one of the 14 clinicians made both extraction and nonextraction decisions. (The single clinician who made decisions of only one kind was clinician 4 who was in fact responsible for only a single decision.)

In a further attempt to identify differences in performance by different clinicians, a logistic re- gression was performed testing the null hypothesis that clinicians did not differ in their propensity to extract. By its nature, this procedure considered only the disagreement or borderline groups in the adolescent and adult cohorts (i.e., the cases listed in Tables IV, A2 and IV, B2). For the 51 subjects in the disagreement groups of two cohorts combined, the null hypothesis that clinicians did not differ in their propensity to extract was strongly rejected (p < 0.006), conditional logistic regression 39 with effects for case and clinician), indicating that within the borderline groups, the extraction/nonextraction ratios for different clinicians did in fact differ. At the extremes, for example, clinician 6 opted for extraction in only 21 of the 50 cases that he evaluated (42%), whereas clinician 1 opted for extraction in 28 of the 36 cases that he evaluated (78%). These differences in clinician performance were strong enough to be detected in each cohort taken individually (p < 0.01 for the adolescent co- hort; p < 0.05 for the adult cohort):

It is also of interest to examine the related question of whether some clinicians tended to de- cide in the minority a larger proportion of the time than others. There were two possible ways in which an individual clinician could have disagreed with a majority consensus for any given patient. He could have been either the only one who disagreed in a 1:4 (or 4:1) decision, or one of two who disagreed in a 2:3 (or 3:2) decision. The incidence of these occurrences is displayed in Table VI. It may be seen that clinicians voted with the majority about 9 times in 10 overall and that when 2/3 and 3/2 splits

Table VI. Minority decisions by clinician (minority votes/total votes)

Less 3/2 and Clinician no. All decisions 2/3 splits

1 3/36 1/29 2 2/37 0/29 3 5/69 2/61 4 0/1 0/1 5 11/80 6/66 6 4/50 1/44 7 8/74 4/64 8 11/92 4/77 9 2/20 0/17

10 4/46 1/36 11 7/85 1/72 12 13/85 5/71 13 6/52 1/42 14 1/13 0/12

TOTALS 77/740 26/621

Significance* ns (p > 0.10) ns (p > 0.10)

*Probability that one or more clinicians differs from the others more than chance.

were excluded, they voted with the majority 19 of 20 times. Overall there is no strong evidence that different clinicians decided in the minority to dif- ferent degrees (p > 0.10 for all decisions and also for all decisions less 3/2 and 2/3 splits, Fisher's exact tests for 14 x 2 tables).

DISCUSSION

The most striking finding reported here is an unexpectedly high incidence of agreement among a group of orthodontists in deciding whether or not to extract in the permanent dentition. The level of agreement observed under actual clinical condi- tions appears to go far beyond that usually encoun- tered in theoretical verbal or written statements by comparable groups of clinicians.

The propensity of clinicians to extract more readily for adult subjects than for adolescent sub- jects is particularly interesting when one considers that there is much less empirical information avail- able on the long-range consequences of orthodon- tic intervention in adults than there is for adoles- cents. Indeed, it seems fair to note that there is as yet no independent theory of adult orthodontic treatment other than that which has been adapted from our previous experience with younger sub- jects. It would seem reasonable to hypothesize that the greater tendency to opt for extraction in the adult cohort is in some substantial way related to the shared belief of clinicians that residual growth

308 B aum r ind et al. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics March 1996

potential in adolescent subjects can be harnessed in treatment in such a way as to avoid the necessity for extraction. To the extent that such reasoning is appropriate, one would predict (other things being equal), that the "older" adolescent subjects are when treatment is begun, the stronger will be the tendency of the clinicians to opt for extraction. This prediction is amenable to later testing with already available data.

The large number of subjects for whom the clinicians believed surgical intervention might be indicated was a real surprise. For 37 of the 148 subjects (25%), one or more clinicians identified surgery as at least a probable component of treat- ment. Adolescent and adult subjects were desig- nated for surgical consideration in roughly equal proportions. Probable candidates for surgery were identified in the extraction, nonextraction, and dis- agreement groups of the adolescent cohort and in both the extraction and disagreement groups of the adult cohort. It should be noted that thus far we have little information available on the reasons for the clinician's decisions on surgery and that further examination is indicated.

The disagreements concerning Angle classifica- tion were also interesting. Here the prior expecta- tion that consensus would be very high was not borne out empirically. Instead, clinician disagree- ments on Angle classification were observed in more than 25% of cases scattered widely in the nonextraction, disagreement and extraction groups for both cohorts. In general, clinician consensus about Angle classification appear to tell one little about clinician consensus on extraction. The sharp- est case in point was case 93, which two clinicians characterized as Class I, one clinician called Class II tendency, and one called Class II subdivision left, and one called Class III unilateral right. Yet not- withstanding these different characterizations, all five clinicians agree on extraction (although two different extraction patterns were suggested). These findings are consistent with the assertion of many experienced observers that the Angle classi- fication system does not of itself constitute a set of diagnostic categories. 4°

CONCLUSION

This article has sought to supply useful infor- mation about the performance of one group of orthodontists in making an important treatment decision for a representative group of orthodontic patients. Because the data are drawn from actual clinical experience, the conclusions involve a mini-

mum number of assumptions and are probably highly representative of the performance of this particular group of clinicians at this particular time. How much we can generalize from this group of clinicians to all orthodontists is not yet known and will be the subject of further investigation. A final caveat is appropriate: The data thus far presented do not tell us the r easons for the clinicians' deci- sions and do not tell us the degree to which the decisions were correct . Data on the correctness of the clinicians' decisions will only become available after the completion of treatment. Data on the clinicians' stated reasons for reaching their deci- sions have already been collected and will be pre- sented in a subsequent publication.

REFERENCES

1. Weinberger BW. Orthodontics: an historical review of its origin and evolution. St Louis: CV Mosby, 1926.

2. Angle EH. Treatment of malocclusion of the teeth. 7th ed. Philadelphia: SS White Manufacturing, 1907.

3. Stallard H. Dental articulation as an orthodontic aim. J Am Dental Assn Dental Cosmos 1937;24:347-76.

4. Case CS. The question of extraction in orthodontia (1911 debate). AM J ORTHOD 1964;50:658-91.

5. Angle AH. Forward to the first edition. In: Strang RHW, Thompson WM, eds. Textbook of orthodontia. Philadel- phia: Lea & Febiger, 1958.

6. Grieve GW. Analysis of malocclusion based upon the for- ward translation theory. AM J ORTHOD ORAL SURG 1941; 27:323.

7. Grieve GW. Anatomical and clinical problems involved where extraction is indicated in orthodontic treatment. AM J ORTHOD ORAL SURG 1944;30:437-43.

8. Tweed CH. The application of the principles of the edgwise arch in the treatment of malocclnsions Parts I & II. Angle Orthod 1941;11:5-67.

9. Tweed CH. Indications for extraction of teeth in orthodon- tic procedure. AM J ORTHOD ORAL SURG 1944;30:22-45.

10. Brodie AG. Reminiscences. Angle Orthod 1947;17:44. 11. Andresen V. The Norwegian system of functional gnatho-

orthopaedics. Acta Gnathol 1936;1:4-36. 12. Kloehn SJ. Guiding alveolar growth and eruption of teeth to

reduce treatment time and produce a more balanced den- ture and face. Angle Orthod 1947;17:10-33.

13. Creekmore TD. Inhibition or stimulation of the vertical growth of facial complex, its significance to treatment. Angle Orthod 1967;37:285-97.

14. Jacobsson SO. Cephalometric evaluation of treatment effect on Class II, Division I malocclusions. AM J ORTHOD 1967; 53:446-55.

15. Poulton DR. The influence of extraoral traction. AM J ORTHOD 1967;53:8-18.

16. Kuhn RJ. Control of anterior vertical dimension and proper selection of extraoral anchorage. Angle Orthod 1968;38:341.

17. Harvold EP, Vargervik K. Morphogenetic response to acti- vator treatment. AM J ORTHOD 1971;60:478-90.

18. Pfeiffer JP, Grobety D. Simultaneous use of cervical appli- ance and activator: an orthopedic approach to fixed appli- ance therapy. AM J ORTHOD 1972;61:353-73.

American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics B a u m r i n d et al. 309 Volume 109, No. 3

19. Frankel R. Decrowding during eruption under the screening influence of vestibular shields. AM J ORTHOD 1974;65:372- 406.

20. Root TL. JCO interview on headgear. J Clin Orthod 1975; 9:20-41.

21. Woodside DG, Reed RT, Doucet JD, Thompson GW. Some effects of activator treatment on the growth rate of the mandible and position of the midface. Trans 3rd Int Orthod Congr London, 1975, Crisby Lockwood Staples, pp. 459-480.

22. Teuscher V. A growth related concept for skeletal Class II treatment. AM J ORTHOD 1978;74:258-75.

23. Buonocore MG. Principles of adhesive retention and adhe- sive restorative materials. J Am Dent Assoc 1963;67:382-91.

24. Miura F, Nakagawa K, Masahara E. New direct bonding system for plastic brackets. AM J ORTHOD 1971;59:350.

25. Cueto HI. A little bit of history: the first direct bonding in orthodontia. AM J ORTHOD DENTOFAC ORTHOP 1990;98: 276-7.

26. Perry CK Jr. TMJ dysfunction l i t igation-Pandora 's Box opens up. J Mich Dent Ass 1988;70:533-8.

27. Machen DE. Orthodontic treatment and facial appearance. AM J ORTHOD DENTOFAC ORTHOP 1991;99:185-6.

28. Wheeler PW. Risk preclusion. AM J ORTHOD DENTOFAC ORTHOP 1992;101:194-5.

29. Hahn GW. Orthodontics: its objectives, past and present. AM J ORTHOD ORAL SURG 1944;30:401-28.

30. Hellman M. Fundamental principles and expedient compro- mises in orthodontic procedures. AM J ORTHOD ORAL SURG 1944;30:429-43.

31. Brodie AG. Does scientific investigation support the extrac- tion of teeth in orthodontic therapy? AM J ORTHOD ORAL SURG 1944;30:444-60.

32. Pollock HC. The extraction debate of 1911 by Case, Dewey and Cryer. AM J ORTHOD 1964;50:656-7.

33. Korn EL, Baumrind S. Randomized clinical trials with clinician-preferred treatment. Lancet 1991;337:149-52.

34. Paquette DE, Beattie JR, Johnston LE. A long-term com- parison of nonextraction and premolar extraction edgwise therapy in "borderline" Class II patients. AM J ORTHOD DENTOFAC ORTHOP 1992;102:1-14.

35. Kelly J, Harvey C. An assessment of the teeth of youths 12-17 years. DHEW Pub No (HRA) 77-1644. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics, 1977.

36. McLain JB, Profitt WR. Oral health status in the United States: prevalence of malocclusion. J Dent Educ 1985;49: 386-96.

37. E1-Mangoury NH, Mostafa YA. Epidemiologic panorama of malocclusion. Angle Orthod 1990;60:207-14.

38. CYTEL StatXact users manual--Version 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: CYTEL Software Corp., 1991.

39. Preston DL, Lubin JH, Pierce DA. EPICURE risk regres- sion and data analysis software. Seattle, Washington: Hiro- Soft International Corp., 1990.

40. Katz MI. Angle classification revisited 1: Is current use reliable? AM J ORTHOD DENTOFAC ORTHOP 1992;102: 173-9.

Reprint requests to: Dr. Sheldon Baumrind Department of Growth and Development Craniofacial Research Instrumentation Lab 1525 Walnut St. Berkeley, CA 94709

AAO MEETING CALENDAR

1996 - Denver, Colo., May 11 to 15, Colorado Convention Center 1997 - Philadelphia, Pa., May 3 to 7, Philadelphia Convention Center 1998 - Dallas, Texas, May 16 to 20, Dallas Convention Center 1999 - San Diego, Calif., May 15 to 19, San Diego Convention Center 2000 - Chicago, II1., April 29 to May 3, McCormick Place Convention Center 2001 - Toronto, Ontario, Canada, May 5 to 9, Toronto Convention Center 2002 - Baltimore, Md., April 20 to 24, Baltimore Convention Center