The Crisis in U.S. Army Aviation - VTOL

Transcript of The Crisis in U.S. Army Aviation - VTOL

6 VERTIFLITE January/February 2012

The U.S. Department of Defenseoperates the most advanced fleetof military rotorcraft in the world,

and they have been among the keys tothe success of combat operations in Iraqand Afghanistan. U.S. Army aircraft,primarily rotorcraft, have flown over 4.5million combat hours in the 10 years ofconflict.

The latest model aircraft are state-of-the-art in mission systems capabilities.The AH-64D Apache Block III had its firstproduction aircraft delivery inNovember 2011, and incorporatesdozens of technology insertions,including improvements to the avionics,communications, engine power,transmission and rotor blades. The CH-47F Chinook, fielded in 2007, is similarlymuch advanced over its non-upgradedsiblings, with a digital cockpit, a digitalautomatic flight control system, etc. TheUH-60M Black Hawk, with hundredsdelivered to the Army since 2006, alsoincorporates improvements to theengines, blades and cockpits. Theupgrades to each of these frontlineaircraft were made possible by thefunds freed-up from the cancelation ofthe RAH-66 Comanche in 2004.

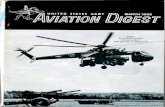

But there is a crisis brewing. Thesemodernized aircraft are limited updatesto old aircraft designs. The Chinook justcelebrated its 50th anniversary. Theprototype for what would become theOH-58 Kiowa first flew in 1962, the BlackHawk first flight was in 1974 and theApache in 1975. The Army has notdeveloped a new rotorcraft since, andthere are no new starts in theacquisition system. (Even the off-the-shelf UH-72A Lakota – the militaryversion of the EC145 – is a derivative ofthe BK117, which first flew in 1979.)

While these upgraded aircraft aredesperately needed, the gap betweenoperational needs and existingcapabilities continues to widen.

The Army has the majority of rotarywing aircraft – over 4,000 of the 6,000DoD fleet – and have historically beenthe lead military Service in developingnew platforms, but they are not alone intheir path towards growing shortfalls.The Navy is introducing the new MH-60S and MH-60R Seahawks stuffed withstate-of-the-art avionics, but they arealso based on older model Hawks.

The V-22 Osprey is the only newcombat rotorcraft that DoD has fieldedin more than 25 years. It was a clean-sheet design that developed afundamentally new architecture.Although it just became operational in2007, even its technology base is aging,with the first Osprey prototype havingflown in 1989, over 20 years ago. TheMarine Corps is also modernizing itsother aircraft, benefitting from highlevel leadership, constancy of purpose,and lower fleet production costs (due totheir relatively smaller quantities). Butalthough the UH-1Y, AH-1Z and CH-53Ksharing little commonality with previousgenerations, they are still limited byconstraints from the original aircraft

designed in the 1950s and 60s.

In 1992, the “Tri-Service Science andTechnology Reliance,” or ProjectReliance, designated the U.S. Army as

the lead for rotorcraft S&T efforts –however, no additional funding camewith this and the other military Servicescurtailed their science and technologyefforts. S&T budgets have been starvedfor the past two decades with theaverage since 1992 about half of what itwas during the previous two decades(adjusting for inflation). Furthermore,the Army soon focused much of its S&Tefforts to support the Comanche in the1990s, as well as unmanned systems inthe 2000s. After ten years of war and theServices forced by necessity to solvecritical near-term problems,development of next generationtechnologies and designs haveatrophied. Rotary wing aircraft havebeen doing tremendous work in theater,but they have not gotten the prioritywith investments for future capabilities.

All of the aircraft designs are old, andmany in-service airframes are old aswell. The archetypical example isChinook prototype #8 – its first flightwas in 1963. It was then configured asCH-47A model, upgraded to a B modelin 1966, a C model in 1978, and then a Dmodel in 1992. It served multiple toursin Vietnam, as well as Haiti, Bosnia andAfghanistan. It is still flying today withthe 101st Aviation Regiment, with over3600 flight hours since its last reset.Current plans have it flying for anothertwo decades or more – 75 years ofservice. And aircraft like this are not justold – they’re also tired. The extremelyhigh operational tempo’s impact onrotorcraft airframes is somewhat akin to“dog years.”

The Crisis in U.S. Army AviationBy Mike Hirschberg, Executive Director

The V-22 Osprey isthe only new combatrotorcraft that DoDhas fielded in morethan 25 years.

Vol. 58, No. 1 7

During the Vietnam War, the Army builthuge numbers of UH-1 Huey and AH-1Cobra aircraft to compensate foroperational gaps. More importantly forthe future, however, critical S&Tinvestments were also made that led tonext generation aircraft – the UH-60 andthe AH-64 – despite declining budgets.They provided tremendous leaps incapability over the prior generation, butmodern combat has exposed thelimitations of today’s fleet: over 400aircraft and nearly 600 lives have beenlost in the past decade of conflict. Sadly,DoD sent hundreds of rotorcraft intocombat without complete or effectiveaircraft survivability equipment – andonly the Comanche cancelation andhigh operational losses started therectification plan. In addition, the lack ofperformance in the extremeenvironments of Iraq and Afghanistanprecipitated more losses in non-hostileaccidents than from enemy fires. Thepower losses from high temperaturesand high altitudes, as well as sand-induced brownouts, could all beremedied with technology.

A detailed Pentagon study, theFuture Vertical Lift (FVL) CapabilitiesBased Assessment (CBA), identified 55significant gaps between operationalneeds and existing capabilities. This andprevious studies – as well as 10 years ofwar – have shown the need forimprovements in speed, range, payload,endurance and altitude, as well assituational awareness and automation,survivability and supportability. Withoutstrong leadership to develop nextgeneration capabilities, these gaps willcontinue to grow.

At the Army Aviation Symposiumby the Association of the UnitedStates Army (AUSA) in January,

Major General Tony Crutchfield,commanding officer of the Army’sAviation Center of Excellence and FortRucker in Alabama, stated that the Armyhad “the best equipment in the world”but each system was headed forobsolescence by 2040. GeneralCrutchfield laid out his Vision 2030 toaddress the continued cycle of blockupgrades and modernization efforts,saying it “has to be a revolutionarychange, not an evolutionary one.”

So, where is the revolutionarycapability? The FVL Strategic Plan laysout an overarching vision, to replaceessentially all DoD rotorcraft with nextgeneration systems over the next 25-40years. Once signed by the DeputySecretary of Defense, industry will havea clear roadmap of DoD’s intent fordevelopment of future vertical liftaircraft. This will enable industry to alignIndependent Research andDevelopment (IRAD) budgets with thegoals and timelines set forth. It alsoallows the Services and US SpecialOperations Command to pool theirresources to mitigate the gaps that theFVL CBA has identified. But the StrategicPlan has to be signed. The commitmenthas to be made. The DoD leadershipmust take a “big picture” view andexercise the leadership needed toemplace and execute the Strategic Plan.Without this, individual Service effortswill likely be insufficient to reach a nextgeneration capability, leaving a crisis ofperpetual evolutionary upgrades.

The FVL vision begins with themedium class of aircraft – nextgeneration replacements for theApache, Black Hawk, Seahawk, Huey,Cobra, etc – which has the largestnumber of existing aircraft (around4,500). The Army has already steppedout along this objective, with the Navy,Marine Corps, and Special Operationsalso participating. It has alreadyproduced a draft joint Initial CapabilitiesDocument (ICD), awarded four contractsfor Joint Multi-Role (JMR) studies, and

plans to award one or more contractsnext year for technology demonstratorsto fly in the 2017 timeframe. The Navy isinvestigating the opportunity to investas well – which could allow threecompletely separate vertical lifttechnology paths to be pursued. Thechallenges of Joint Service designs areconsiderable – significant powermargins for high altitude operations,large payloads, long ranges, high speedsand the ability for the aircraft to operatefrom ships. But Joint solutions will bethe key to successfully developing nextgeneration platforms in the constrainedbudgets of the foreseeable future.

FVL/JMR is the future. Sustainedleadership from the Army, Navy, MarineCorps, Special Operations Commandand the Office of the Secretary ofDefense is crucial to avert a crisis offuture obsolescence. Reaching anoperational capability of a nextgeneration rotorcraft by 2030, when ourcurrent systems begin to reachobsolescence, requires vision today andtwo decades of constancy of purpose.DoD, the U.S. Congress, industry andacademia must remain united in theirvision for the future. We can’t affordanother Comanche, with decades ofdevelopment that don’t result in aproduct. We must succeed. We cannotafford to fail to act now, with conviction,commitment and competent execution.The lives of our sons and daughtersdepend on it.

The Chinook first flew in September 1961. A half-century later, the CH-47F has beencompletely modernized, but visually remains virtually unchanged.