The Budget Squeeze C. Eugene Steuerle The Urban Institute September 10 Stanford Institute for...

-

Upload

barbra-richard -

Category

Documents

-

view

273 -

download

7

Transcript of The Budget Squeeze C. Eugene Steuerle The Urban Institute September 10 Stanford Institute for...

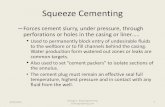

The Budget Squeeze

C. Eugene SteuerleC. Eugene Steuerle

The Urban InstituteThe Urban Institute

September 10September 10

Stanford Institute for Economic Policy ResearchStanford Institute for Economic Policy Research

OUTLINE WHERE WE WERE IN 2000WHERE WE WERE IN 2000

Sources of Pressure: Revenues, Health, Retirement Programs, Future Sources of Pressure: Revenues, Health, Retirement Programs, Future Labor Force Growth SlowdownLabor Force Growth Slowdown

Retirement & Health: Not Well TargetedRetirement & Health: Not Well Targeted Everything Else in Budget SqueezedEverything Else in Budget Squeezed Impact on Democracy: Dead Men RulingImpact on Democracy: Dead Men Ruling

TRENDS SINCE 2000TRENDS SINCE 2000 Tax Cuts, Drug Benefits, Defense & International, Other Revenue Tax Cuts, Drug Benefits, Defense & International, Other Revenue

ShortfallShortfall $800 Billion Annual Shift from Surplus to Deficit $800 Billion Annual Shift from Surplus to Deficit

The Squeeze TightensThe Squeeze Tightens THE IMPLICATIONSTHE IMPLICATIONS

Private: Restructuring of Labor MarketPrivate: Restructuring of Labor Market Public: Fundamental (Trillion Dollar) Shifts in Policy Public: Fundamental (Trillion Dollar) Shifts in Policy

Federal Revenues by Source as a Percentage of GDP,1934-2008

Individual Income Taxes

Corporate Income Tax

Social Insurance and Retirement

Receipts

Excise Taxes* Other**

0.0%

3.0%

6.0%

9.0%

12.0%

15.0%

18.0%

21.0%

1934 1938 1942 1946 1950 1954 1958 1962 1966 1970 1974 1978 1982 1986 1990 1994 1998 2002 2006

* Includes receipts from highway, airport, telephone, alcohol, and tobacco.** Includes estate and gift taxes, customs duties, and miscellaneous receipts.Source: Eugene Steuerle and Adam Carasso, The Urban Institute, 2003. Historical data based on the Budget of the UnitedStates Government, FY 2004 and projections based on CBO's January 2003 budget projections.

Social Security

Medicare

Medicaid

0.0%

2.0%

4.0%

6.0%

8.0%

10.0%

12.0%

14.0%

16.0%

18.0%

20.0%

22.0%

24.0%

1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070 2075

Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid Outlays as a Percentage of GDP, Fiscal Years 1950-2075

Pressures from Elderly Programs People have been retiring earlierPeople have been retiring earlier People are living longerPeople are living longer Birth rates have fallenBirth rates have fallen Annual/lifetime benefits continue to riseAnnual/lifetime benefits continue to rise Health services grow & expand (quantity)Health services grow & expand (quantity) Healthcare insurance system reduces Healthcare insurance system reduces

downward price pressures normal for a downward price pressures normal for a growing industry (price)growing industry (price)

Social vs. Legal Pressures

Only the change in birth rates indicates a Only the change in birth rates indicates a growing growing need need in society.in society.

The other five are signs of increased well-The other five are signs of increased well-being or legal promises to pay out more.being or legal promises to pay out more.

68.7

64.1

50

55

60

65

70

1950 2000

INDIVIDUALS RETIRE EARLIER:AVERAGE AGE AT WHICH MALE WORKERS BEGIN RECEIVING

SOCIAL SECURITY BENEFITS

Source: Social Security Administration, Annual Statistical Supplement to the SocialSecurity Bulletin, 2001. Table 6.B5.

Life Expectancy at the Early Retirement Age

10

12

14

16

18

20

22

24

26

28

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 2060

Year of Retirement

Ave

rage

Num

ber o

f Yea

rs L

ived

in R

etire

men

t

Men Women

Source: Adam Carasso and C. Eugene Steuerle, The Urban Institute, 2003. Based on mortality data from the Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary.

OASI Benefit for a One-Earner Couple in First Year of Retirement

$0

$5,000

$10,000

$15,000

$20,000

$25,000

$30,000

$35,000

$40,000

$45,000

$50,000

1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 2060

Year Cohort Turns 65

Co

nsta

nt 2

00

2 D

olla

rs

High Wage (160%)

Average Wage (100%)

Low Wage (45%)

Source: Adam Carasso and C. Eugene Steuerle. The Urban Institute, 2003. Update of C. Eugene Steuerleand Jon M. Bakija, Retooling Social Security for the 21st Century, Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, 1994.

Quantity Indexes: 2000 Growth Over 1950

448%

2,779%1,611%

899%

19,000%

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

Total personalconsumption

Telephone &telegraph

MEDICALCARE

Recreation Video, audio,& computers

Quantity Indices Over Time: Medical Care vs. Other Consumption Categories

Price Indexes: 2000 Growth Over 1950

494%

118%180%

-79%

1,074%

-200%

0%

200%

400%

600%

800%

1000%

1200%

Total personalconsumption

Telephone &telegraph

MEDICALCARE

Recreation Video, audio,& computers

Pe

rce

nt

Gro

wth

Be

twe

en

20

00

an

d 1

95

0

Price Indices Over Time: Medical Care vs. Other Consumption Categories

—Real 2002 Dollars—

* Expected rather than realized benefits. Notes: The “average” wage profile is a hypothetical profile routinely employed by the Social Security Administration in its analyses. Data are discounted to present value at age 65 using a 2 percent real interest rate. Table assumes survival to age 65. Projections based on intermediate assumptions of the 2002 OASDI and HI/SMI Trustees Reports. Source: C. Eugene Steuerle and Adam Carasso, The Urban Institute, 2002.

$23,000$0$23,000$160,000$0$160,000$15,0001960

$530,000

$360,000

$250,000

Soc. Security Lifetime Benefits

$490,000

$240,000

$80,000

Medicare Lifetime Benefits

$1,020,000

$600,000

$330,000

Total

Lifetime Benefits

$640,000

$345,000

$63,000

Total Lifetime

Taxes

$500,000

$290,000

$61,000

Soc. Security Lifetime

Taxes

$140,000

$55,000

$2,000

Medicare Lifetime

Taxes

$18,0001970

$38,0002030

$25,0002000

Soc. Security Annual Benefits

Year Cohort

Turns 65

Social Security and Expected* Medicare Benefits for Average-Wage, Two-Earner Couple

Number of Workers Available to Support Each Social Security Beneficiary

3.7 workers per beneficiary in 1970

3.3 workers per beneficiary in 2003

1.8 workers per beneficiary in 2080

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070 2080

Wo

rke

rs p

er

be

ne

ficia

ry

Source: Table IV.B2, "Covered Workers and Beneficiaries," from the 2002 and 2003 OASDI Trustees Report.

Annual Growth Rate (% over Period) 2000–10 2010–20 2020–30

1.08 0.38 0.38

Labor Force Projections (Annual Growth Rates)

Labor Force Projections (Annual Growth Rates)

Adult Employment Rate (Absent Changes in Retirement Patterns), 1950-2040

40%

45%

50%

55%

60%

65%

70%

1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 2030 2040

Note: Projections show what happens if there is a change in age-specific employment rates as the population ages.Source: C. Eugene Steuerle and Adam Carasso, The Urban Institute, 2002. Based on data from the U.S. Bureaus of Censusand Labor Statistics.

Example of Shift in Resources Upon Retirement

For a worker who earns $50,000…

Increases in Resources Transferred from OthersSocial Security Benefits $18,500Medicare Benefits $5,000

Total 1 $23,500

Decrease in Resources Transferred to OthersSocial Security Taxes -$7,700Federal Income Taxes -$6,600Other Taxes (Including State and Local) -$4,000

Total 2 -$18,300

Net Change in Transfers Received (Total 1 - Total 2) $41,800

Addendum: Additional decline in retiree's after tax earnings $31,700

otherw ise available to meet current and future needs

One Possible Reprieve

Despite debates over capital (individual Despite debates over capital (individual accounts), the main problem is laboraccounts), the main problem is labor

Many so-called elderly are middle-agedMany so-called elderly are middle-aged They still want to be productiveThey still want to be productive Government estimates may seriously Government estimates may seriously

understate potential labor demand for these understate potential labor demand for these workersworkers

30%

35%

40%

45%

50%

55%

60%

65%

70%

75%

1948 1953 1958 1963 1968 1973 1978 1983 1988 1993 1998

All 20+ Males 55+

Labor Force Participation: Males Aged 55 and Older vs. the Adult Population,1948-99

Multiple Gains if Work Expands

Fewer beneficiariesFewer beneficiaries More national output, divided into:More national output, divided into:

More taxes for elderly programsMore taxes for elderly programs More taxes for children’s and other More taxes for children’s and other

programsprograms More private wealth & income to be More private wealth & income to be

spread over fewer retirement years.spread over fewer retirement years.

Male Labor Force Participation Rates, 1940-2001

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

1940 1945 1950 1955 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005

Pe

rce

nt i

n L

ab

or

Fo

rce

Men with 16.4 years of life expectancyMen age 65

Source: C. Eugene Steuerle, Adam Carasso and Meghan Bishop, The Urban Institute, 2002. Based on data from the U.S. Social Security Administration, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the U.S. Census of Population.

Men age 65 in 2001 under either measure

Age 58.5 in 1940

Medicare introduced in 1966Early retirement available

Constricted Choices Among Elderly Programs Locked-in guarantees and growth rates Locked-in guarantees and growth rates

preventprevent taking better care of truly oldtaking better care of truly old removing inequities among beneficiariesremoving inequities among beneficiaries switching money toward long-term careswitching money toward long-term care removing elderly from povertyremoving elderly from poverty

48%

62%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

19681997

Proportion of Social Security Benefits for Males Going to Those with More Than 10 Years of Life Expectancy

Some Inequities

Current system discriminates:Current system discriminates: single heads of householdsingle heads of household

• receive less than married persons who receive less than married persons who contribute no more to systemcontribute no more to system

two-earner couplestwo-earner couples • receive fewer benefits for the same levels of receive fewer benefits for the same levels of

contribution when their earnings are split contribution when their earnings are split some divorced personssome divorced persons

• receive no share of their spouses’ benefits if receive no share of their spouses’ benefits if married fewer than 10 yearsmarried fewer than 10 years

Long-term “Long-term” Care

There does remain a serious long-term care There does remain a serious long-term care issue for the very oldissue for the very old

By providing increasing amounts to those By providing increasing amounts to those relatively younger, current system actually relatively younger, current system actually makes problem harder to solvemakes problem harder to solve

Comparison of Average Benefits, Poverty Level, and Elderly Poverty Rate

$8,917

$11,140

$8,628$8,6287.8%

4.2%

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

Early 1990s 2020

In C

onst

ant 2

002

Dol

lars

0.0%

2.0%

4.0%

6.0%

8.0%

10.0%

Pov

erty

Rat

e

Avg. Benefit Poverty Level Poverty Rate

Composition of Federal Outlays, 1950-2008

Medicaid, Veterans, and Other Health

Medicare

Social Security

Other Retirement, Disability, and Income

Security

Net Interest

Defense

All Other

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1950 1954 1958 1962 1966 1970 1974 1978 1982 1986 1990 1994 1998 2002 2006

All Other

Defense

Net Interest

OtherRetirement,Disability, andIncome SecuritySocial Security

Medicare

Medicaid,Veterans, andOther Health

Total Retirement, Health, & Income Security

Source: Eugene Steuerle and Adam Carasso, The Urban Institute, 2003. From the Budget of the U.S. Government, FY 2004.

Federal Outlays as a Percentage of GDP, 1962-2002

Defense and International

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002

Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002

Net Interest

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002

Other Domestic

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002

Domestic Discretionary

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002

Means-Tested Entitlements

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002

Other Entitlements

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002

Other Domestic Outlays as a Percentage of GDP, 1962-2002

Reduction in Outlay Category as a Percentage of GDP, 1961-2002

Table 3: Reduction in Outlay Category as a Percentage of GDP, 1961-2002

Function and Subfunction Peak Year Maximum 2002 % ChangeNational Defense 1968 9.43% 3.37% -64%International Development and Humanitarian Assistance 1964 0.53% 0.08% -86%General Science, Space and Technology 1966 0.89% 0.20% -77%Energy Conservation 1981 0.02% 0.01% -64%Natural Resources and Environment 1977 0.51% 0.28% -44%

Dead Men (yes, they were men) Rule

Priorities set yesterday for the needs of Priorities set yesterday for the needs of tomorrowtomorrow

Voters left with fewer choicesVoters left with fewer choices Unable to switch priorities (defense, Unable to switch priorities (defense,

education, homeland security, children)education, homeland security, children)

"Which Federal Baseline Do We Use?"

Baseline Receipts

2001 Tax Law Extended

2002 Tax Law Extended

2003 Tax Law Extended

Other Tax Laws Extended

Alternative Minimum Tax Growth Halted

16%

17%

18%

19%

20%

21%

1970 1977 1984 1991 1998 2005 2012 2019 2026 2033 2040 2047 2054 2061 2068 2075

% o

f G

DP

Source: Steuerle, Carasso, Bishop, based on data from Gale, Orszag, and the Tax Policy Center..

The Assumption "Gap"

Old Baseline

Baseline with All Tax Law Changes

16%

17%

18%

19%

20%

21%

1970 1977 1984 1991 1998 2005 2012 2019 2026 2033 2040 2047 2054 2061 2068 2075

% o

f G

DP 3.3%

Source: Steuerle, Carasso, Bishop, based on data from Gale, Orszag, and the Tax Policy Center..

Baseline Receipts Meet Major Spending Initiatives

Adjusted Baseline Receipts

Baseline SS, M'Care, & M'Caid

Includes Rx Bill and M'Care Fix

Includes Baseline Defense, Internat'l

Interest

Includes new Defense estimate

Adjusted Baseline Spending (includes

new Interest estimate)

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

1970 1977 1984 1991 1998 2005 2012 2019 2026 2033 2040 2047 2054 2061 2068 2075

% o

f GD

P

Source: Steuerle, Carasso, Bishop based on data from Reischauer, OMB, CBO.

Lower Receipts and More Spending Move the "Cliff" Up from 2041 to 2011

Baseline Receipts (OLD)

Baseline SS, M'Care, M'Caid, Defense, Internat'l, Interest

(OLD)

Baseline Receipts

(ADJUSTED)

Baseline Spending (ADJUSTED)

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

1970 1977 1984 1991 1998 2005 2012 2019 2026 2033 2040 2047 2054 2061 2068 2075

% o

f G

DP

Source: Steuerle, Carasso, Bishop based on data from Reischauer, OMB, CBO.

Focus in on the "Cliff" (2000-2015)

Baseline Receipts (OLD)

Baseline SS, M'Care, M'Caid, Defense, Internat'l (OLD)

Baseline Receipts (ADJUSTED) 2011

Baseline Spending (ADJUSTED)

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

% o

f G

DP

Source: Steuerle, Carasso, Bishop based on data from Reischauer, OMB, CBO.

Focus in on the "Cliff" (2000-2015)

Baseline Receipts (OLD)

Baseline SS, M'Care, M'Caid, Defense, Internat'l (OLD)

Baseline Receipts (ADJUSTED) 2011

Baseline Spending (ADJUSTED)

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015

% o

f G

DP

Source: Steuerle, Carasso, Bishop based on data from Reischauer, OMB, CBO.

SOON…VERY SOON

ANYANY spending spending

on education, environment, welfare, community on education, environment, welfare, community development and most domestic programs development and most domestic programs

must be paid for out of:must be paid for out of: Deficits (but this can only be temporary)Deficits (but this can only be temporary) Rescinding of tax cuts or tax Rescinding of tax cuts or tax increasesincreases Pared growth in retirement and health spending Pared growth in retirement and health spending A very small international and defense presenceA very small international and defense presence

CONCLUSION Dead Men Rule by locking in future changes Dead Men Rule by locking in future changes Rest of government squeezed between lower taxes and higher Rest of government squeezed between lower taxes and higher

retirement/health spendingretirement/health spending Education/environment/discretionary programs get leftovers, Education/environment/discretionary programs get leftovers,

if anyif any Automatic government (spending tomorrow’s money today) Automatic government (spending tomorrow’s money today)

restricts choices amongrestricts choices among programs in generalprograms in general elderly programs as wellelderly programs as well

Fundamental restructuring of public budgets and private labor Fundamental restructuring of public budgets and private labor markets almost inevitablemarkets almost inevitable Will it be done well? Will it be done well?