The Broad, Los Angeles’s Snazzy New Museum - The New Yorker

-

Upload

southwestern-college-slide-library -

Category

Documents

-

view

214 -

download

0

Transcript of The Broad, Los Angeles’s Snazzy New Museum - The New Yorker

Save paper and follow @newyorker on Twitter

The Art World

SEPTEMBER 28, 2015 ISSUE

Going DowntownEli Broad opens his own museum in Los Angeles.

BY PETER SCHJELDAHL

T

Works by Jeff Koons and Christopher Wool on the thirdfloor, where the lighting—natural and artif icial—adjusts automatically.COURTESY BRUCE DAMONTE / THE BROAD / DILLER SCOFIDIO +RENFRO

he Broad, it’s called: a snazzy new museum ofexcellent contemporary art, which just opened in downtown Los Angeles, right

across the street from the Museum of Contemporary Art. If that sounds redundant,consider that, a few miles away, on Wilshire Boulevard, the Los Angeles CountyMuseum of Art also features a contemporary collection, as does, a bit farther west, theHammer Museum. Besides being no more than fifty years old, all these institutions—along with the wondrous Walt Disney Concert Hall, designed by Frank Gehry, whichstands next door to the Broad—have in common histories of the patronage and theaggressive, sometimes resented, influence of the billionaire philanthropist and collectorEli Broad.

Few individuals whose surnames aren’t Medici have had such dramatic effect on the artculture of an important city. The new museum crowns a particular passion of Broad’s: tocreate a cultural center for Los Angeles along a stretch of Grand Avenue, which alsoboasts the Music Center—home to the Disney hall and three other venues—and theHigh School for the Visual and Performing Arts. The words “Los Angeles” and “center”consort oddly, especially since the city’s ever more apocalyptic traffic further dulls thelocal citizens’ never ardent yen to venture out of their usual ways. Nor does GrandAvenue feel like anybody’s idea of an agora. There are busy Latino and Asianneighborhoods nearby, but, after hours, you don’t encounter many people in the spottilygentrified downtown area (and a considerable number of those you do are homeless). Atany time on the avenue, even cars are relatively sparse. Yet the dream of culture-cravingthrongs persists. The Broad offers free admission. Synergistically, MOCA has eased tenserelations with its chief patron to grant free yearlong memberships to all who visit theBroad during the first two weeks. (Broad bailed out the foundering institution in 2008,but the director he selected departed under a cloud of acrimony, two years ago.)

The museum is well worth a visit now and periodic revisits later, as its exhibits cycle

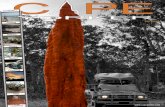

The museum is well worth a visit now and periodic revisits later, as its exhibits cyclethrough a collection of some two thousand works by about two hundred artists. Aroundtwo hundred and fifty pieces are currently on display. Whomever Broad and his wife,Edythe, collect, they collect in depth. The show’s roughly chronological arrangementincorporates several rooms devoted to single artists, like pocket retrospectives. Thebuilding, by the New York firm of Diller Scofidio + Renfro, plays changes on a themethat the architects call “the veil and the vault”—masking what amounts to a storagefacility for the collection. The façade is a slewed honeycomb of concrete modules: slitlikeholes set in diagonal channels, which suggest the tidy claw marks of a very large cat. Thebuilding’s capacity to impress is muted by the material Ninth Symphony of the Gehryconcert hall, but it’s pleasant enough.

You enter through a dim lobby with dark-gray, Surrealistically curved walls and ceiling.The lobby leads to shapely ground-floor galleries and offers the choice of a cylindricalglass elevator or a hundred-and-five-foot escalator—low-impact thrill rides—to the vast,columnless third floor, which is beautifully illuminated by automatically adjusted blendsof natural and artificial light. The interior walls stop short of the skylight-riddled ceiling,conveying a temporary and flexible character. The vault portion of the building occupiesthe second floor. You catch sight of it through glass walls when you descend a hushed,snaking, umbilical-like stairwell: a cavernous space of racks and equipment, yieldingglimpses of art works at rest between shows. It’s a nice touch, like a backstage pass at theopera.

The Broad museum, in downtown Los Angeles.COURTESY IWAN BAAN / THE BROAD / DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO

Broad, now eighty-two, and Edythe arrived in L.A. in 1963, from their home town ofDetroit. The son of a union organizer who came to own dime stores, Broad started ahome-building firm that ascended to the Fortune 500, as did a subsequent startup infinancial services. (A how-to-succeed memoir, published in 2012, shares his secret in itstitle, “The Art of Being Unreasonable.” His friend Michael Bloomberg wrote the

introduction.) Edythe introduced him to art, hesitantly. She wanted an Andy Warhol

VIEW FULL SCREEN

introduction.) Edythe introduced him to art, hesitantly. She wanted an Andy Warholsoup-can print, but worried that her husband would be appalled by the price: a hundreddollars. (They later parted with $11.7 million for a soup-can painting.) In 1972, theybought a van Gogh drawing, but Broad tired of it and arranged a swap for a rugged earlypainting by Robert Rauschenberg. The couple’s taste gravitated to Pop art—they ownthirty-four works by Roy Lichtenstein—and to socially conscious, left-liberalsensibilities. (“I’m not as liberal as I used to be,” Broad told me, when I spoke with him atthe museum, but he remains a Democrat.) He is rare among collectors in possessingabundant terrific works by the late Leon Golub, a painter of white-mercenary criminalityin developing-world locales. The museum’s inaugural show presents a large charcoaldrawing, by Robert Longo, from a photograph taken last year in Ferguson, Missouri, inwhich police advance, at night, in a fog of tear gas.

Once committed to collecting, the Broads anchored their holdings with canonical worksby Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Cy Twombly, and Ellsworth Kelly. Twombly and Kellyaside—and excepting a more recent fondness for Albert Oehlen and Mark Grotjahn—they shied from abstraction, and skated lightly over Conceptualist art of the nineteen-seventies. In the eighties, the Broads went in big for neo-expressionist and PicturesGeneration artists, notably Jean-Michel Basquiat and Cindy Sherman. (They own ahundred and twenty-four pictures by Sherman.) The German artists Joseph Beuys,Anselm Kiefer, Georg Baselitz, and Thomas Struth are also strongly represented, andrecent New York stars in the collection include Christopher Wool, John Currin, GlennLigon, and Kara Walker. But, with the prominent exceptions of Ed Ruscha, JohnBaldessari, Mike Kelley, Chris Burden, Charles Ray, Robert Therrien, and Lari Pittman,the Broads have braved local exasperation by not going out of their way to boost L.A.artists.

There’s not much installation art on view, but there is one gem: “The Visitors” (2012), bythe Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson. The piece consists of nine gorgeous, hour-longvideo projections, placed at odd angles in a dark room, of as many musicians, sitting inseparate rooms in a dilapidated mansion, and noodling with a love song. Theexquisiteness of sight and sound and the pathos of the musicians’ shared lonelinessbrought tears to my eyes when I first saw the piece, at the Luhring Augustine Gallery,two years ago. Would that happen again, during a note-taking tour of a jam-packedmuseum? It did.

Broad’s favorite contemporary artist seems to be Jeff Koons, whose works he owns inprofusion—from encased vacuum cleaners, floating basketballs, and a stainless-steelinflated bunny to a huge, color-tinted, stainless-steel rendering of tulips and theinevitable balloon dog. Broad came to Koons’s rescue in the nineties, at a tough time—financially and personally—for the artist, and paid a million dollars for several futureworks that he waited years to receive. He calls Koons’s output “bold and theatrical,”words that could well be engraved on a cornerstone of the museum; Broad adores punch.

The sometimes bitterly voiced controversies that surround Koons seem to concern him

The sometimes bitterly voiced controversies that surround Koons seem to concern himnot at all. It’s in Broad’s nature, when crossed or confronted, to plow forward withundeterred aplomb. He appears immune to grudges, seldom keeping for long the enemieshe can’t help but make. (A history of scraps with Frank Gehry, in particular, has notobviated expressions, at least in public, of amity on both sides.) Koons’s sunny dispositionand shame-free panache suit Broad, as does his work’s insouciant symbolizing ofoligarchic noblesse oblige. Why would anyone gainsay immense wealth when looking atthe delightful things that may be done with it? ♦

Peter Schjeldahl has been a staff writer at The New Yorker since 1998and is the magazine’s art critic.

![Why Work [New Yorker]](https://static.fdocuments.in/doc/165x107/577cdacb1a28ab9e78a68a26/why-work-new-yorker.jpg)