Techniques for Performing Caesarean Section

-

Upload

febrinata-mahadika -

Category

Documents

-

view

90 -

download

6

description

Transcript of Techniques for Performing Caesarean Section

-

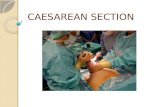

Techniques for performing caesarean section

Karumpuzha R. Hema* MBBS, MRCOGSta Grade in Obstetrics

Richard Johanson* BSc, MA, MD, MRCOGSenior Lecturer in Obstetrics

North Staordshire Hospital NHS Trust, Stoke on Trent ST4 6QG, UK

In many countries caesarean section has become the mode of delivery in over a quarter of allbirths. Safety of the mother and cost are the two main areas of concern. Various studies on thetechniques of performing a caesarean section have focused on reducing the operating time,blood loss,wound infection and cost.Given the fact that caesarean section is themost commonlyperformed operation in obstetrics, it is important that trainers and trainees are familiar withthe basic surgical techniques and that best practice is followed. At the same time surgeonsshould take necessary precautions to reduce their risk of exposure to Hepatitis B and HIV.The skin incision and entry into abdominal cavity is best achieved by the modified Cohens

incision. The lower segment transverse uterine incision has stood the test of time over a periodof 75 years and remains the best way to enter the uterus. Closure of the uterus in single layerappears to be acceptable, whenever technically possible. Placental delivery should be bycontrolled cord traction after spontaneous expulsion. Closure of the visceral and parietal layersof the peritoneum no longer seems to be necessary. Obliteration of space in the subcutaneouslayer, either by suture or by suction, seems to reducewound disruption. These issues are beingconsidered in the CAESAR randomized controlled trial of surgical techniques currentlyunderway in England.Prophylactic antibiotics are mandatory in preventing post-operative morbidity. Many of the

above mentioned steps have been tested in randomized trials. Further studies are needed toexamine awide range of questions arising from this review, e.g. best position of the patient, thevalue of exteriorization of the uterus whilst repairing the uterus, and the use of agents to relaxthe uterus in dicult deliveries.

Key words: caesarean section; methods; materials; complications; research.

Ever since the wider introduction of caesarean section in the latter part of the 19thcentury, the safety of the procedure has improved. Indeed, confidence in safety1 hasincreased to the point that, in some countries, nearly a quarter of all deliveries arenow being conducted by the abdominal route.2 There is currently widespread debateabout the relative merits of abdominal and vaginal delivery3 and this discussion is dealtwith in depth in Chapter 9.

15216934/01/01001731 $35.00/00 *c 2001 Harcourt Publishers Ltd.

Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & GynaecologyVol. 15, No. 1, pp. 1747, 2001doi:10.1053/beog.2000.0147, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on

2

*Address for correspondence: Clinical Governance Support Oce, North Staordshire Hospital NHS Trust,Ward 58, Maternity Unit, Newcastle Road, Stoke on Trent ST4 6QG, UK.

-

Improved safety is related to the availability of antibiotics and blood transfusion1 andalso to advances in anaesthesia, as well as to improvements in technique. The principalcomplications are haemorrhage and infection and these, in turn, are related to thecomplexity of each case. Prolonged labour, prolonged rupture of membranes andincreased frequency of vaginal examinations all predispose to infection. Previouscaesarean section, placenta praevia and placenta accreta increase the risk of haemor-rhage. In general, the risks and complications are greater for emergency than forelective procedures. Generic risks relate to excessive speed and lack of surgicalexperience in performing the operation.While surgical techniques do vary from surgeon to surgeon, good adherence to

basic surgical principles and an awareness of recognized methods of performingcaesarean sections will minimize morbidity. Caesarean section is widely accepted to bemore expensive than vaginal delivery4,5, and limiting morbidity will reduce costs. Thischapter deals with techniques for caesarean section, including the relevant aspects ofthe basic surgical principles and suturing techniques. In addition, we addresscomplications of caesarean section. Issues related to anaesthesia and preparation for theanaesthetic are dealt with separately in Chapter 8.

IDENTIFICATION OF EVIDENCE

For the purposes of this chapter we have carried out the following review of theliterature. The Cochrane Library and the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials(RCTs) were searched for relevant RCTs, systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Asearch of MEDLINE from 1970 to 1999 was also carried out. The databases weresearched using the relevant MeSH terms: caesarean, repeat caesarean section andmethods.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Good practice dictates that the operator should have full knowledge of the patientshistory, especially in relation to any previous surgery. Highlighting the relevant pointsof history, and risk factors, on the delivery page in the maternity record will drawattention to potential diculties. In dierent situations, the exact operative techniquechosen will vary. Factors determining the need to individualize practice includegestational age, fetal presentation and position, size and number of fetuses, maternalhealth and the perceived degree of urgency. Anticipation and proper planning areimportant keys to the avoidance of complications. Careful explanation to the motherof the planned operation prior to surgery and a resume after the procedure constitutegood clinical practice and are essential risk management. It is clearly very important tohave appropriate assistance and a readiness to call for help when presented withdiculties.On the basis of surgical studies, it is evident that the choice of correct suture

material may enhance healing. However, there are no published randomized con-trolled trials on suture material for caesarean section. Nevertheless, the generalprinciple of choosing a material with sucient tensile strength is accepted. Naturalthreads, such as catgut, have largely been replaced by synthetic materials. This isbecause they have been shown to cause an inflammatory reaction and because theymay harbour infection and also lose their strength capriciously. The non-absorbable

18 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

synthetic polyamide sutures cause very little reaction and retain their strength reliably.These sutures decompose in tissue by hydrolysis rather than phagocytosis.6 Thecommonly used monofilament sutures are polypropylene (Prolene), polydioxanone(PDS) and polyglyconate (Maxon). The commonly used multifilament sutures arepolyglactin 910 (Vicryl) and polyglycolic acid (Dexon).Regardless of the actual material chosen, the knot is the weakest link in the suture.

This is the site of maximum foreign body reaction aecting the adjacent layers of tissue.Although knot security is important, especially whenmonofilament materials are used,multiple throws beyond the breaking point should be avoided. It has been shown thatknot-holding capacity is maximal with all materials after the addition of a maximum oftwo throws to any of the starting knots.7 Any additional throwwill leave extra amountsof suture material, leading to increased foreign body reaction. However, when vanRijssel et al8 examined suture size and knot volume, they found that the use of thickgauge suturematerial addedmore than the addition of extra throws to the total amountof foreign body and tissue reaction.9 They also examined dierent types of knot andfound that, throw-for-throw, square knotswere superior to slip knots (see Figure 1) butthat an additional throw to a sliding knot improved its security. Use of the surgeonsknot (Figure 1) is thought to increase the holding power of the first throw and preventslippage and is also considered helpful when there is a high risk of the suture tearingthrough a delicate structure. On the other hand, in laboratory studies, the security ofthe surgeons knot was not found to be superior to square knots.8

Asepsis, minimal and meticulous handling of the tissue, perfect haemostasis and re-approximation of the layers without strangulation are essential steps that should befollowed.10 Dehiscent wounds are almost always found with unbroken sutures andintact knots, which have cut through the tissue, having been tied too tightly or havingbeen placed too close to the edge.7 The best scar results when wound edges, whichretain good blood supply, are opposed without tension or trauma and with aminimum of foreign material.Lyon and co-workers, in a review that spanned three decades, showed thatmorbidity

could be reduced by improving surgical technique. They decreased the needle size used,switched to polyglycolic sutures, avoided using laparotomy packs (the packs may causeabrasions, leading to formation of adhesions), used sharp dissection and paid attention tothe basic rules of surgical practice in minimizing damage to tissues.11

The problemof latex sensitization should be considered in all obstetric patients. Chenand co-workers, in their interesting study, found that nine of 333 obstetric patientsshowed latex-specific immunoglobulin E. When details about atopy, exposure tocondoms, previous deliveries and operations were obtained, it was evident that a

Figure 1. Knots commonly used in surgical practice.

Techniques for performing caesarean section 19

-

previous caesarean delivery wasmore frequent in latex-sensitized patients with positivelatex-specific immunoglobulin E (33 versus 8.4%; P5 0.05). Patients with atopy andadditive risk factors should be treated in a latex-free environment to avoid latexsensitization.12

PROTECTING HEALTH PERSONNEL

Precautions are important to avoid risks associated with exposure to, or inoculation of,body fluids e.g. human immunodeficient virus. Any contact with sharp objects by thesurgeon and assistants should be kept to a minimum. The use of scissors rather than ascalpel for extending incisions in the fascia, peritoneum and myometriummay be safer.After use, sharp instruments need to be transferred in a basin or a tray, to avoid injury.Retraction of tissues using instruments may be safer than using a hand. Needlestickinjuries can be prevented bymounting the needle onto the holder for transfer after use,by using forceps to re-position the needle and by mounting the tip and the eye of theneedle together while not in use (Figure 2). If counter-pressure is needed while posi-tioning a needle, either a tissue forceps or a metal thimble on a finger can be used. Theneedle shouldbe cuto andhandedover to the scrubnursebefore tying thefinal knot.10

Although double gloving or the use of thicker gloves does not eliminate the risk ofneedlestick injuries, it helps to reduce the incidence of such injuries.13,14 A randomizedprospective study evaluated the use of surgical pass trays to reduce the incidence ofglove perforations during caesarean section. Surgical team members were assigned topass the instruments in a normalwayor to use a surgical pass tray.Although in this studythe frequency of glove perforations was not reduced by the use of trays, the authorsfound that there were no complete perforations where double glove sets had beenused.15 Smith andGrant reported glove puncture in 54% of caesarean sections, with 60%of these occurring at closure.16 Double gloving reduced the incidence of puncture of theinner glove by a factor of 6. The use of blunt needles and tissue handling by forceps willalso help to reduce needlestick injuries.17 Contact with body fluids can beminimized byusing a drape with a bag on either side to collect the amniotic fluid and the blood. Theuse of a clear plastic shield will protect the surgeon and assistants faces.Double gloving, use of waterproof gloves and the wearing of spectacles all reduce

the risk of exposure and need to be implemented universally.

POSITION OF THE PATIENT

When pregnant women near term lie in the supine position, the uterus may compressthe inferior vena cava, interfering with the venous return to the heart. This, in turn, isthought to result in hypotension, hypoperfusion of the placenta and decreased fetaloxygenation. Hence, it is standard practice that a lateral tilt of 10 to 158 is used whilethe caesarean section is performed. Wilkinson and Enkin, in their Cochrane review18,analysed the limited evidence to support this practice from three (poor quality) trialsinvolving 293 women. When tilt had been used there were fewer low Apgar scoresand better cord pH measurements. However, the authors did not consider theevidence to be sucient for making definitive recommendations about practice.18

Interestingly, a recent study by Mattorras and co-workers found no benefits inperforming emergency sections with left lateral tilt.19

20 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

CATHETERIZATION

Single catheterization before starting the procedure to avoid injury to bladder isrecommended. The use of an indwelling catheter after caesarean section under epiduralis thought to lessen the riskof urinary retention and the need for repeat catheterization.

PREPARATION OF THE SKIN

Infection rates are lowest in cases where shaving is done just prior to the surgery.Depilatory agents have been shown to be better than razor preparation.20 The agent

Using thimble Holding needle

Using forceps tomanipulate needle

Figure 2. Technique to avoid needlestick injuries.

Techniques for performing caesarean section 21

-

used for the skin preparation should be non-toxic, fast acting and easy to apply andshould have broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. Iodophores, such as iodine pluspolyvinyl pyrolidine (povidoneiodine) and tincture of chlorhexidine gluconate (0.5%in 70% isopropyl alcohol), are usually recommended. However, the use of povidoneiodine should be restricted to intact skin as it contains large molecular fractions whichcannot be excreted completely.21 Alcohol and hexachlorophane should be used only ifthere is hypersensitivity to other usually recommended agents. If 10% alcohol is usedon its own as an antiseptic, diathermy should be used only after full evaporation hasoccurred. The use of iodophor-impregnated adhesive film is protective and allowsrapid skin preparation, provided it is not dislodged at surgery.22 Pre-operative skinpreparation along with pelvic irrigation with antibiotics was tested in a randomizedstudy of 100 women.23 No significant dierences in the incidences of wound infectionand endometritis were found in a comparison of two agents (povidoneiodine versusparachlorometaxylenol). However, endometritis occurred significantly morefrequently in the group that did not receive antibiotic irrigation.

SKIN INCISION

Type of incision

Vertical incision

Traditionally, both transverse and vertical incisions have been used for caesareansection (Figure 3). Each type has its own advantages. A vertical incision allows a less

Pfannenstielincision

Cohensincision

Maylard incision

Midline incision

Figure 3. Position of various skin incisions.

22 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

vascular rapid entry and good exposure of both the abdomen and pelvis. This incisionmay be indicated in cases of urgency, such as massive haemorrhage, when upperabdominal exploration is required, and at perimortem caesarean section. It may also beappropriate in patients on systemic anticoagulants or with a coagulopathy and whenthose who refuse blood transfusion are operated on.

Pfannenstiel incision

Pfannenstiel introduced the Pfannenstiel incision in 1900 (see references in Starket al.24). This incision is extensively used because of its excellent cosmetic results, alongwith the benefits of early ambulation and a low incidence of wound disruption,dehiscence and hernia. However, the Pfannenstiel incision involves dissection of thesubcutaneous layer and the anterior rectus sheath and, when extended into theexternal and oblique muscles, may result in injury to the ilioinguinal and iliohypo-gastric nerves.25 In addition, use of this incision limits views of the upper abdomen andmay increase the blood loss and haematoma rate because of the increased dissection.Mowat and Bonnar reported a wound dehiscence rate of 2.94% (48 of 1635) after amidline incision, compared to only 0.37% (two of 540) after a Pfannenstiel incision.26

Similar findings when comparing transverse and vertical incisions have been reportedby other authors. One group found an eightfold increase in post-operative wounddehiscence and infection with the vertical incision.27 On the other hand, when theemergency use of these incisions was tested in a randomized controlled trial, noadvantages of one over the other were seen in terms of wound disruption and herniaformation.21 Ellis in his commentary21a stated that the perceived dierence inmorbidity between transverse and vertical incisions may be attributed to the bias inchoosing the incision type, where midline incisions are chosen for emergencysituations such as haemorrhage, sepsis and trauma. The Pfannenstiel incision continuesto be commonly used to perform caesarean sections, primarily for its cosmetic appealand also for the perceived dierences in outcome.28

Joel Cohens incision

Professor Joel Cohen introduced an incision for abdominal hysterectomy in 1954, andthis incision has since been used widely by obstetricians to perform caesareansections.29 The incision is a straight transverse incision, positioned slightly higher thanthe Pfannenstiel (Figure 3). The subcutaneous tissue is not sharply divided. Theanterior rectus sheath is incised in the midline for 3 cm, but the muscles are notseparated from the sheath. The peritoneum is bluntly opened in a transverse directionand, with the assistants help, the opening is widened by traction in a transversedirection. Cohen and Pfannenstiel incisions were compared in a retrospective study in245 women who underwent caesarean section.29 The length of the operation was lessby 1.6 minutes, and post-operative morbidity was also less in the Cohens incisiongroup (7.4 versus 18.6%; P5 0.05).

Modified Joel Cohens incision

Wallin and Fall30 carried out an RCT of standard and modified Cohens methods ofcaesarean section with 36 women in each group. In the modified Cohens method,they placed the incision 3 cm above the pubic symphysis and bluntly opened theperitoneum (Figure 3). In addition, they did not close the parietal and visceral layers of

Techniques for performing caesarean section 23

-

the peritoneum. They found a reduced intraoperative blood loss (250 versus 400 ml:P 0.026) and a reduced operating time (20 versus 26 minutes; P5 0.001) in themodified Cohens group.The Cohens incision has been examined in a number of RCTs where modifications,

such as single-layer closure of the uterus and non-closure of parietal and visceral layersof peritoneum, have also been evaluated31,32 (Table 1). Darj and Nordstrom com-pared Joel Cohens incision (n 25) with Pfannenstiels incision (n 25) and reportedless operating time (12.5 versus 26 minutes; P5 0.001), less blood loss (448 versus608 ml; P 0.017) and less analgesic requirement (P 0.004) with the Cohensincision.31 The study did not reveal any negative aspects of using the new technique.This technique is well described, with figures, in the paper published by Holmgren,Sjoholm and Michael Stark.32 This package of refinements in techniques was intro-duced by Michael Stark and is known, after a hospital in Jerusalem, as the MisgavLadach method.

Maylard incision

Another transverse approach has been described: the Maylard incision (Figure 4),which involves cutting the rectus muscles transversely and ligating the inferiorepigastric artery to provide good access to the pelvis. This incision was originallydescribed for use in radical pelvic surgery. It is comparable to vertical incisions interms of complications and outcome.33,34 Ayers and Morley, in their randomized trialcomparing Pfannenstiel and Maylard incisions for caesarean sections, did not find anydierence in morbidity.35 They suggested that the Maylard incision is a safe optionwhich should be strongly considered when risk factors are present, such as macro-somia or twins needing maximal exposure for a non-traumatic delivery. Althoughthere was no increase in blood loss and post-operative morbidity with the Maylardincision, it is clear that, because more dissection is required, post-operative discomfortis likely to be greater.10

Inferior epigastricartery and vein

Figure 4. Maynard incision explained. Inferior epigastric vessels ligated and recti muscles cut.

24 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

Length of incision

Whatever type is chosen, the length of the incision should be adequate. A dicultcaesarean section should not be a substitute for a dicult vaginal delivery. The incisionshould be approximately the same length as an Allis clamp, laid on the skin (15 cm).Finan and co-workers showed in their prospective study that the time (uterineincisiondelivery) was shorter in the group that passed the Allis test, compared tothe group that failed the test (mean 58.4 versus 95.7 seconds, P 0.002).36

Previous scars

As already indicated, wound healing is aected if the edges are not approximatedproperly. This becomes an important point to remember whenever previous scars areencountered. Excision of the previous scar will improve wound healing and givesbetter cosmetic results. Bowen and Charnock found, in a series of 25 womenundergoing repeat caesarean section, that the use of a double-bladed scalpel yieldedbetter healing and aesthetically more pleasing scars than the conventional scalpel. Thisis because it uniformly excised the scar tissue and avoided the need for two incisions.An adjusting screw allows the necessary width to be excised37 (Figure 5).

Method of incision

The time-honoured practice of using two scalpels at caesarean section (one for the skinand sheath and a dierent one for internal divisions) has been studied. No dierence inwound infection was found with the use of either one or two scalpels.38 Another studyrevealed that the first scalpel usually remained sterile.39 Whichever scalpel is used, theincision should be made using one stroke rather than with multiple strokes, whichmay lead to infection and poor healing.40

Nygaard and Squatrito21, in their review of methods of abdominal incisions, havediscussed the merits identified in various studies of a scalpel compared to ultrasoundknife, laser or diathermy. Although animal studies have shown that the scalpel is

Figure 5. Double-bladed scalpel.

Techniques for performing caesarean section 25

-

associated with less tissue damage, findings from controlled studies in humans aremixed. The authors comment that, with some exceptions, the bulk of the literature onhumans suggests little advantage or disadvantage to incisionsmadewith scalpel, cautery,or laser.21

Uterine incision

Lower segment transverse incision (Kerr) (Figure 6)

Ever since its introduction in 1926 by Munro Kerr41, the lower segment incision hasbeen the most commonly performed uterine incision. A Doyens retractor is used forgood exposure of the lower segment. The loose fold of peritoneum, where thebladder is attached, should be identified. Before an incision is made, rotation of theuterus should be noted (it is usually dextro-rotated) and, if possible, corrected, so thatthe incision will not be asymmetrical, risking extension on the opposite side. The loosefold of peritoneum should be incised and the bladder pushed down gently with care,mainly in the centre in order to avoid disturbing the vascular plexus.22 In cases ofobstructed labour, with formation of Bandls ring, this fold of peritoneum is locatedhigher and the peritoneum should be opened higher up, with particular care to avoidbladder injury.The uterine incision should be made in the centre, for a length of 23 cm, until the

membranes are exposed. In order to avoid injury to the fetus, the deeper fibres of themyometrium should be opened with the blunt end of the scalpel or with fingers.Extension of the incision should be achieved by fingers along the path of leastresistance. It must be remembered that the force used on the left side should be lessthan that on the right side to avoid haemorrhage from the left angle. This risk canusually be minimized by correcting the dextro-rotation. If sharp dissection is required,the use of thick bandage scissors is recommended for cutting the thick lower segment

Lower segmentincision

Classicalincision

De Leesincision

Figure 6. Position of various uterine incisions.

26 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

in a concave manner to avoid injuring the fetus and the major uterine blood vessels.22

However, Rodriguez and co-workers, in their RCT of blunt versus sharp extension ofthe incision, did not find any dierence in ease of delivery, blood loss, unintendedextension or post-operative endometritis.42 When dicult circumstances areencountered, requiring an extension of the transverse incision, a J-shaped extensioninto the upper segment, on the most accessible side, is better than an inverted Tincision (which will form a weaker scar due to poor healing). However, both of theseincisions have been shown to be frequently associated with intraoperative com-plications and prolonged hospital stays.43

Extension of the uterine decision using an absorbable stapling device, called AutoSuture Poly CS, has been described. After a small incision, the stapling device isintroduced between the membranes and the uterine wall. The stapler is then fired toproduce two columns of absorbable staples. Thereafter, a hysterotomy is performedbetween the rows of the staples. However, in an RCT between the conventional typeand the stapling type of caesarean section, the operating time was prolonged and theother measures of outcome were the same. Hence, its routine use is not recom-mended.44 A Cochrane review analysed four trials involving 526 women where thestapling device was used to extend the incision. There was no dierence in the totaloperating time compared with the other techniques used to extend the incision, butthe stapler increased the time needed to deliver the baby (weighted mean dierence0.85 minutes, 95% Cl 0.48 to 1.23). Blood loss was lower with the stapling device. Thereviewers conclude that there is not enough evidence to justify the routine use of thestapling device to extend the uterine incision. Indeed, there is a possibility that thisdevice could cause harm by prolonging the time to deliver the baby.45

Lower segment vertical incision (De Lee and Cornell) (Figure 6)

The lower uterine vertical incision, introduced by De Lee and Cornell46, has theadvantage of sparing the uterine vessels but it needs careful dissection to reflect thebladder, which may nevertheless become involved in an extension. The incidence ofscar dehiscence is equivalent to that expected with the transverse incision and it maybe regarded as an alternative to the upper uterine vertical incision.46a Shipp and co-workers have also shown that women with a prior lower vertical incision are not at anincreased risk of uterine rupture compared to those who have had a lower transverseincision.47 No statistical dierences in terms of perinatal and maternal morbidity werenoted when singleton breech fetuses were delivered via lower transverse (n 221) orlower vertical incisions (n 195).48 The lower segment transverse incision has alsobeen compared with the vertical incision in triplet pregnancies. In a case-controlledstudy, no significant dierences were observed in perinatal mortality or operativecomplications.49

Because of the risks of bladder extension, it remains advisable to do a lowersegment transverse incision whenever the lower segment is well formed. Where thisis not the case, then a low vertical incision is acceptable.

Classical incision (Figure 6)

In recent years, the rate of classical incision has gone up, due particularly to increasedpreterm deliveries, especially those performed before 26 weeks of gestation or afterrupture of membranes. Bethune and Permezel, in their retrospective studyundertaken over a 9 year period in Melbourne, noted that 1% of all their caesarean

Techniques for performing caesarean section 27

-

sections were classical. The frequency correlated inversely with the gestational age:20% at 24 weeks, 5% at 30 weeks, and less than 1% from 34 weeks onwards.50

The classical upper segment vertical incision is thought to be associated withexcessive blood loss, infection, poor healing and an increased risk of rupture insubsequent pregnancies. However, Blanco and Gibbs found comparable earlymorbidity and wound infection rates between two groups of women who hadlower segment transverse and classical incisions.51 They attributed this to improvedsurgical techniques. Classical sections are indicated when the lower segment isinaccessible due to dense adhesions or large fibroids. This route may also be necessarywith preterm breech presentations or with a transverse lie and prolonged rupture ofmembranes (particularly those that are dorsoinferior). Placenta praevia in general isno longer regarded as an indication for a classical section22, but this incision should beundertaken at perimortem caesarean (Table 1).

Delivery of the fetus

In an observational study of 105 deliveries, inductiondelivery intervals of more than8 minutes under general anaesthetic and incisiondelivery intervals of more than3 minutes under both general or spinal anaesthetic were associated with increasednumbers of low Apgar scores and neonatal acidosis.52 The same group found that withlonger uterine incisiondelivery intervals, umbilical arterial (UA) noradrenalineconcentrations increased significantly, resulting in lower UA pH values.53 However,Vatashsky and co-workers (n 568) and Anderson and co-workers (n 204)concluded after their studies on the influence of incisiondelivery interval that itdid not significantly aect the outcome.Both a high head and a deeply engaged head could pose problems with delivery.

Ideally, the fetal head should always be delivered in an occipito-anterior position.Management of the dicult situations that may arise in this area are discussed later inthis chapter. When faced with diculties, a general principle is that uterine relaxationmay help. Glyceryl trinitrite has been used intravenously in a randomized double-blindtrial at elective caesarean section.54 Although routine administration of glyceryltrinitrite in elective cases did not have significant benefits, there were no significantmaternal or fetal side-eects to the drug. In the light of this finding, it may be worthtrying this in dicult deliveries.Injury to the fetus during caesarean section is not uncommon and is often under-

reported. These injuries are likely to occur at the time of uterine incision or atextraction of the fetus. The legal literature contains several cases involving scalpwoundsresulting from incisions during caesarean section. Such injuries cannot be considered asexpected complication.55 Durham and co-workers even reported an iatrogenic braininjury during emergency caesarean section. There have also been reports of long bone

Table 1. Classical caesarean section: possible indications.

Preterm delivery with poorly formed lower segmentPremature rupture of membranes, poor lower segment and transverse lieTransverse lie with back inferiorLarge cervical fibroidSevere adhesions in lower segment reducing accessibilityPostmortem caesarean sectionPlacenta praevia with large vessels in lower segment

28 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

fractures and of extensor tendon laceration in preterm neonates.55,56 The use of a newlydevised, blunt-edged, notched scalpel has been shown to be easy and safe for makinguterine incisions (Figure 7).57 Therewere nomajor complications or fetal injuries whenthe authors used this tool in 41 women at caesarean delivery.

Delivery of the placenta

Traditionally the placenta is removed manually at the time of caesarean section. Themethod used should not be any dierent from the controlled cord traction used atvaginal delivery. Manual shearing of the placenta does not allow time for retraction ofthe myometrial fibres, and hence leads to unaltered perfusion and increased blood loss.Four randomized trials comparing manual extraction and controlled cord traction forexpulsion of the placenta have been undertaken5861 (Table 2).Wilkinson and Enkin, in their systematic Cochrane review, conclude that manual

removal of placenta at section may do more harm than good by increasing maternalblood loss and increasing the risk of infection.62 In a recent study, Lasley and co-workersfound that post-operative infections occurred in 25 of 168 (15%) women in thespontaneous group compared with 44 of 165 (27%) in the manually delivered group(relative risk 0.6%, 95% confidence interval 0.4 to 0.9, P 0.01). The incidence ofinfection in the sub-group of women with ruptured membranes significantly increasedin the manual extraction group (20 versus 38%, relative risk 0.5. 95% Cl 0.3 to 0.9,P 0.02).61Yancey and co-workers isolated non-staphylococcal bacteria from surgeons gloves

soon after fetal extraction in 11 out of 14 labouring women, as compared to one of 11non-labouring women.63 Based on this finding, Atkinson and co-workers conducted arandomized study in a large number of patients (n 643) who were divided into fourgroups. In this study the eects of a glove change for surgeon and assistant, just after

Figure 7. Blunt-edged notched scalpel.

Techniques for performing caesarean section 29

-

delivery of the fetus, along with a spontaneous delivery of the placenta, were comparedto a policy of manual removal and no glove change. Although they found that changinggloves was not associated with a reduced incidence of post-operative endometritis, theyconfirmed that manual removal was associated with a greater risk of post-caesareanendometritis64 (Table 2). In a smaller study which looked at intraoperative glovechange no significant dierenceswere noted inmeasures of post-operativemorbidity.65

The practice of exploring the uterus with a gauze sponge after delivering theplacenta (to check for retained placental cotyledons or membranes) has not beentested properly. This practice could theoretically increase the chances of bacterialcontamination and hence post-operative endometritis. However, as the uterus is wellcontracted at this stage, the chances of bacterial inoculation deep into the decidua andthe myometrium are small.61 At elective caesarean section, some operators choose todilate the cervix with fingers or dilators after delivery of the placenta. This practice hasnot been tested in randomized trials and could, theoretically, introduce infection andcause damage to the cervix.

Exteriorization of the uterus

Exteriorization and traction on the uterus has been shown to reduce blood loss andfacilitate suturing.66 However, exteriorization may cause nausea and vomiting andsome women do complain of pain. Using Doppler monitoring, a significantly higherincidence of venous air embolism was reported by Handler and Bromage.67 The theoryof this can be explained: traction enlarges the uterine sinuses and raises the incision toa level higher than that of the heart, and this increases the hydrostatic gradient,thereby promoting venous air embolism.68 Prospective trials of exteriorization of theuterus to repair the uterine wound have been evaluated by Enkin and Wilkinson, whofound that, because of unsatisfactory randomizations and unspecified exclusions, there

Table 2. Placental delivery.

SubjectNumber ofpatients Country Author Year Result

Spontaneous expulsion/manual extraction

31/31 USA McCurdy &co-workers59

1992 Less blood loss;lower incidence of post-operative endometritis

Spontaneous versus manualplacental removal combinedwith exteriorization/in-siturepair (four groups)

100 USA Magann &co-workers60

1993 Less blood loss and post-operative morbiditywith spontaneousexpulsion and in-siturepair

Spontaneous versus manualextraction combined withglove change/no glovechange after delivery of thefetus (four groups)

760 USA Atkinson &co-workers64

1996 No significant change inmorbidity with orwithout glove change;lower incidence ofendometritis withspontaneous placentaldelivery

Spontaneous expulsionversus manual extraction

168/165 USA Lasley &co-workers61

1997 Lower incidence of post-operative infections withspontaneous expulsion

30 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

were insucient data to permit definitive conclusions about exteriorization.69

However, a recent RCT (n 194), which avoided the major drawbacks of previousstudies, indicated that maternal morbidity was not increased with exteriorization70

and in another recent RCT (involving 316 women) the authors found no significantdierences in post-operative wound sepsis, pyrexia, blood transfusion or length ofhospital stay. They concluded that, with eective anaesthesia, exteriorization is notassociated with significant problems and is associated with less blood loss (p5 0.05).71

Closure

Suturing of the uterus

Traditionally the uterine wound is closed, as was recommended by Kerr in 192641, intwo layers. The traditional two-layer suturing technique was borrowed directly fromthe initial vertical incision closure.22 Until fairly recently, recommendations variedonly in terms of the method of actual suturing: locking, continuous or interrupted. In1976 Pritchard and MacDonald72 first noted that a satisfactory approximation of theedges can be obtained by a single-layer closure. Theoretically, single-layer closureshould cause less tissue damage, include less foreign material and take less operativetime. Hauth and co-workers72a randomized 906 women and compared the twomethods. Their conclusion was that a one-layered locking suture closure required lessoperative time, (43.8 versus 47.5 minutes (P 0.0003)). In no outcome assessment,such as haemostasis or endometritis, was the two-layer closure superior to the single-layer closure.72 Insertion of interrupted haemostatic sutureswas required for 16womenin each group. The authors recommended a single-layer closure, when anatomicallyfeasible. A single-layer closure can be achieved using a Polyglactin No. 1 suture with alocking or non-locking method. Animal studies, histological and hysterographicstudies, have demonstrated that a single-layer closure provides the best anatomicalresult and the strongest scar.73

Concerns about the integrity of the scar during a subsequent trial of labour aftersingle-layer closure have been examined in a retrospective cohort study of 292 women(149 after a one-layer closure and 143 after a two-layer closure).74 Tucker and co-workers found that asymptomatic ruptures were not higher in the single-layer group.Eight women had scar dehiscence in the single-layer closure group, as compared to fivein the two-layered closure group.75 Chapman and co-workers studied the outcome ofsubsequent delivery in a group of 164 women who had previously been randomized tosingle-layer closure (n 83) or double-layer closure (n 81). Of these 164women, 145experienced a trial of labour. Therewere no dierences between the two groups duringa subsequent trial of labour, in terms of maternal or fetal outcome measures.76

The classical incision needs to be closed in three layers because of its thickness andvascularity. Traditionally about six all layer interrupted sutures are placed but nottied. Thereafter a herring-bone suture is used for the deep and middle layers. Thesuperficial myometrium and serosa are then juxtaposed by a non-locking continuoussuture, followed by ligation of the all layer interrupted sutures (see Figure 8).

Peritoneal closure

The traditional arguments for peritoneal closure have included, first, restoring theanatomy and approximation of tissues for healing, and second, the re-establishment of

Techniques for performing caesarean section 31

-

a peritoneal barrier to reduce the risk of wound herniation or dehiscence. In addition,peritoneal closure was thought to minimize the formation of adhesions.77

Buckman and co-workers have shown that deperitonealized surfaces heal withoutpermanent adhesions. The closure of peritoneum at the time of caesarean section hasbeen examined in four RCTs. The Cochrane review byWilkinson and Enkin concludedthat there seems to be no significant dierence in short-term morbidity with non-closure of the peritoneum at caesarean section and that non-closure of the peritoneumsaved operating time (weighted mean dierence of 612 minutes, 95% Cl 8.00 to4.27). There was a consistent, although non-significant, trend for improvedimmediate post-operative outcome.78,79 The results of the trials that have now beenpublished are given in Table 3. It is evident that non-closure of the parietal and viscerallayers of peritoneum is likely to be cost eective, time saving and, above all, associatedwith less post-operative morbidity, as well as requiring less analgesia.7883

Closure of fascia

The rectus sheath is commonly closed using a synthetic suture. Wound healing is bestif the stitches are inserted 10 mm from the edge and 10 mm apart. This is becausecollagenolysis occurs over an area of 10 mm from the wound edge. Any woundclosures constructed within this zone will therefore be weaker.10

Closure of Campers fascia

Wound infection can cause disruption of the wound, requiring opening and drainageand a protracted healing time. The formation of seromas and haematomas due to thedead space in the subcutaneous layer can lead to infection. Del Valle and co-workers,in their RCT conducted on 438 women, used 3-0 pain catgut continuous suture toapproximate the Campers fascia. They found that wound disruption was less in thisgroup, compared to the non-closure group, (2.7 versus 7.4%; P 0.03).84 However, noanalysis was made in terms of the depth of the subcutaneous tissue.84 In another

a

b

Figure 8. Closure of classical section. (a) All layer suture; (b) Herring-bone suture.

32 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

prospective trial, 245 women with a subcutaneous space of 2 cm or more wererandomized to closure of subcutaneous space with a 3-0 polyglycolic acid suture or tonon-closure. The incidence of infections in the two study groups, from all causes, was14.5% in the closure group compared to 26.6% in the non-closure group (RR 0.5, 95%Cl 0.30.9).71,85 An alternative to suturing Campers fascia is to leave a drain abovethe sheath with continuous suction. An RCT was conducted by Saunders and Barclayin 200 women undergoing lower segment caesarean section.86 They placed a Redivacdrain behind the sheath and closed the sheath with Polyglactin sutures. They did notfind any significant advantage to the routine use of the drain in non-obese patients.86

The use of closed suction drainage in obese women (42 cm subcutaneous tissue) hasbeen shown to reduce wound complications.87

Table 3. Peritoneal closure.

SubjectNumber ofpatients Country Author Year Result

RCT between non-closure versus closureof parietal layer

127/121 USA Pietrantoni &co-workers122

1991 Shorter operating time;no dierence inmorbidity

RCT of non-closureversus closure ofvisceral and parietallayers

117 USA Hull andVarner123

1991 Reduced need for post-operative analgesia;quicker return of bowelfunction

RCT of non-closureversus closure ofvisceral and parietallayer

300 Switzerland Luzuy et al124 1994 Shorter operating time(P5 0.005); shorterhospitalization

RCT of both layerclosure versus non-closure 1 year post-opfollow-up

192/179 UAE Grundsell &co-workers81

19911994

Less post-operativefebrile morbidity; lesswound infection(P5 0.001); shorteroperating time(P5 0.01)

RCT non-closure/both layers closure

96/94 Malaysia Ho & co-workers125

1997 No dierence in post-operative morbidity;shorter operating time

RCT double-blindstudy (post-operativepain assessment)

21/19 Denmark Hjberg &co-workers82,83

1996/1998

Overall, no dierence inpost-operative pain; useof analgesicrequirements reducedin non-closure groupfrom 3rd day

RCT non-closure/closure of visceralperitoneum

262/287 Austria Nagele &co-workers126

1996 Lower febrile andinfectious morbidity;shorter operating time;use of analgesicrequirements reducedin non-closure group

RCT closure/nonclosure of the visceraland parietal layers

137/143 Canada Irion &co-workers127

1996 Lower post-operativemorbidity and pain;shorter operating time

Techniques for performing caesarean section 33

-

Closure of skin

Skin edges of the incision can be approximated either by intracutaneous sutures,staples or clips, or by subcuticular sutures. The choice is usually based on the surgeonspreference, speed and cosmetic advantage. The subcuticular suture has particularadvantages based on its cosmetic appeal. In studies which compared sutures and staplesat the time of laparotomy (with a vertical incision), subcutaneous polydioxanone (PDS)was found to give the best results.88 A non-randomized Danish study compared threemethods of skin closure. The best cosmetic outcome, from both the mothers andsurgeons perspective, was obtained with subcuticular sutures.89

The first randomized trial, looking at Pfannenstiel incision closure at caesareansection was conducted by Frishman and co-workers on 50 women; it compared stapleswith subcuticular polyglycolic acid sutures. The patients who had subcuticular suturingfelt less pain at discharge and at the post-operative visit (P5 0.01 and P 0.002). Thesubcuticular repair was cosmetically more attractive to both the patients and thesurgeons at the post-operative visit (P 0.04, P 0.01).90 A prolene subcuticularsuture has the advantage over Dexon that it can be removed in the early post-operative period22, but this suture has not been tested in randomized trials.The use of cyanoacrylate (a skin glue) to close the skin at caesarean section has

been evaluated in a series of 44 patients. In this case-controlled study, using nylon andsilk, the authors found cyanoacrylate to be safe and ecient, reducing both the timeand cost of skin closure.91 Further evaluation is required.Delayed closure has been proposed where there are significant concerns about ooze

into the wound. Brigg and colleagues studied the eects of primary versus delayedclosure in cases of HELLP (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets)syndrome, and at the same time they compared Pfannenstiel and midline incisions.In this study, they found that the wound complication rate was not influenced by skinincision or timing of skin closure.92

THE MISGAVLADACH METHOD OF CAESAREAN SECTION

As indicated above, a number of dierent features discussed in this section contributeto the MisgavLadach method of caesarean section. The whole procedure can besummarized as follows.The principal features followed include the Joel Cohen method of opening the

abdomen, suturing the uterus in one layer and non-closure of visceral and parietallayers of peritoneum. Holmgren and co-workers carried out a retrospective compara-tive study between this method and the conventional method (Pfannensteil incision,with two-layered uterine closure of both the peritoneal layers).32 They concluded thatthe incidence of febrile morbidity, adhesions and analgesic requirements was lower inthe MisgavLadach method. The method is well described and the steps are illustratedin figures by the authors in their article.32

Table 4 summarizes the methodology and results of various trials related to thistechnique of caesarean section. The details of these have already been separatelydiscussed in the text. The advantages of this approach include a quicker post-operativerecovery, lower febrile morbidity and antibiotic requirement, early return of bowelmovements and fewer adhesions.

34 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

FUTURE RESEARCH INTO TECHNIQUE

A randomized factorial trial is under way in the United Kingdom, organized by theNational Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, in Oxford, called the CAESARean trial. Thisis based on an initial survey undertaken among obstetricians which determined(a) current practice with respect to the techniques used at caesarean section, and(b) what aspects of the operation clinicians would like to see evaluated in a randomizedcontrolled trial. The trial will assess the following three pairs of alternative surgicaltechniques (1) single versus double-layer closure of the uterus, (2) closure versus non-closure of the pelvic peritoneum, and (3) restricted versus liberal use of sub-sheath drain(The CAESAR study Protocol, National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, Oxford).

ANTIBIOTICS IN CAESAREAN SECTION

Prophylactic antibiotics for caesarean section have been shown to reduce the incidenceof maternal post-operative infectious morbidity. In a systematic Cochrane review onthis subject, 51 trials were analysed.93 The odds ratio (95% Cl) for their eect on

Table 4. Study of combinations of methods.

SubjectNumber ofpatients Country Author Year Result

RCT of single-layer uterineclosure and non-closure ofperitoneum versus double-layeruterine closure and visceral andparietal layer closure

100/100 Israel Ohel &co-workers80

1996 Less operative time(32+ 11 versus44+ 16); less post-operative sedation

RCT of two surgical techniques.Joel Cohens entry, single, non-locking uterine closure, non-closure of both peritoneal layersversus Pfannenstiels opening,single uterine layer and closureof both peritoneal layers

149/153 Italy Franchi &co-workers74

1998 Less operating time;less wound infection

RCT of MisgavLadach method.Joel Cohens entry, singleuterine layer, locking suture,non-closure of peritoneumversus Pfannenstiels incision,double-layer uterine closureand closure of both parietal andvisceral layers

25/25 Sweden Darj &Nordstrom31

1998 Less operating time;reduced blood loss(P 0.017); lessanalgesicrequirement

RCT MisgavLadach method.Cohens entry, single lockinguterine closure versus non-closure of peritoneuminterrupted skin closure; lowermidline incision double uterinelayer closure with closure ofboth parietal and visceral layers

339 Tanzania Bjjorklund &co-workers128

2000 Less operating time;less blood loss

Techniques for performing caesarean section 35

-

serious infectious morbidity/death is 0.25 (0.110.56). The particular antibiotic that isused does not appear to be very important. Both ampicillin and first-generationcephalosporins have a similar ecacy, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.27 (95% Cl: 0.841.93). In comparing ampicillin with a second- or third-generation cephalosporin, theodds ratio was 0.83 (95% Cl: 0.541.26) and in comparing a first-generationcephalosporin with a second- or third-generation agent the odds ratio was 1.21(95% Cl 0.971.51). A multiple-dose regimen for prophylaxis appears to oer no addedbenefit over a single-dose regimen; OR 0.92 (95% Cl 0.701.23). Systemic and lavageroutes of administration appear to have no dierence in eect; OR 1.19 (95% Cl 0.811.73). In addition, the reviewers conclude that there is a need for an appropriatelydesigned randomized trial to test the timing of administration of antibiotics immediately after the cord is clamped versus pre-operatively.93

Similar studies will not necessarily have the power to assess these questions. Forexample, a study by Rizk and co-workers concluded that administration ofprophylactic antibiotics at elective sections (61 placebo versus 59 sections) was notassociated with any reduction in post-operative morbidity.94 Similarly, Rouzi andcolleagues, in their placebo-controlled RCT (211 elective sections and 230 emergencydeliveries), found that routine use of a single dose of cefazolin is eective in emergencysections but not in elective deliveries.95 Studies such as these contribute to the debateabout the need for universal prophylaxis. It may not be necessary in units that canprove that they have low infection rates. Interestingly, if follow-up extends to thecommunity, even units with high rates of prophylaxis continue to have late infec-tions.96 Further research should have longer term outcomes and not just hospital-based infection rates.

COMPLICATIONS DURING CAESAREAN SECTION

The rising caesarean section rate in the past two decades indirectly vouches for itssafety. Nevertheless, it is associated with increased morbidity for the mother, and theprocedure can result in serious complications. The need for blood transfusion isgreater when trainees perform caesarean sections without supervision.97 Yet this is anoperation commonly performed by trainees and residents. A regular review of themethods used, along with good supervision and, where available, periodic training in askills laboratory, will all help to reduce complications.The following were identified as risk factors for complications at caesarean section:

excessive speed, lack of experience, gestational age532 weeks, ruptured membranesand low station of the presenting part. The Confidential Enquiries into MaternalMortality have consistently referred to the need for senior obstetricians to be involvedearly in the event of complications.98 Ideally, all high-risk cases should be performedduring the daytime, when the availability of expertise is maximum. Anticipation is thekey to avoidance of complications.99 Complications are increased in emergencyprocedures. A comparative series from Cape Town suggested that the relative risk formortality, after excluding medical disorders and major antenatal complications, ofintrapartum emergency versus elective sections, was 1.7:1.0.100

There can be diculties encountered at various stages while performing anabdominal delivery. These include: dicult entry into the peritoneal cavity due todense adhesions, diculties associated with obstructed labour, and diculties due tolimited exposure and space in the lower segment. The last problem occurs especially in

36 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

preterm sections with ruptured membranes and with abnormal presentations of thefetus. Each case needs to be managed on an individual basis.

Dicult deliveries at caesarean section

A high head at elective section may give rise to diculty in delivering the fetus. Therule of thumb is to deliver the fetus in a flexed position, very similar to the fetalattitude in utero. In such situations the head can be delivered by applying a pair ofWrigleys forceps, or one forceps blade can be used as a vectis to gently lever out thehead (this blade occupies less space than the hand). The ventouse can also be used toextract the fetus at caesarean section.101 However, in one series this was shown toincrease the incisiondelivery interval and hence caution is necessary.102 In cases ofdirect occipito posterior position, the head should be flexed before delivery and a pairof forceps may need to be used.With face or brow presentations the same principle needs to be applied: flex and

deliver. Breech delivery should be conducted in the same way as vaginal breechdeliveries, using slow and steady traction, avoiding unnecessary speed. Either both feetor one foot (if only one is accessible) need to be grasped and gentle traction will enablea smooth assisted delivery. Delivery of the shoulders needs to be conducted in thesame way as in a vaginal delivery, by gentle rotation. Delivery of the after-coming headcan be dicult, especially in emergency caesareans or after rupture of membranes.The assistant needs to maintain pressure on the fundus of the uterus and Mauriceau-Smellie-Veits technique or forceps delivery may be helpful.With a transverse lie, an external cephalic or podalic version should be tried before

the uterus is incised! If unsuccessful, an internal podalic version will need to beundertaken. It is not very uncommon to find a hand within easier reach than the foot.It is therefore important to identify the limb carefully before beginning an extraction.If a hand is grasped, it needs to be pushed back gently and the delivery should becompleted as a breech extraction.In placenta praevia, when the placenta is encountered anteriorly at the level of

incision, it should simply be pushed aside to expose the membranes. The placenta itselfneeds to be incised only when the former steps are not possible.Where a caesarean section is performed in the second stage of labour or after failed

trial of instrumental delivery, it may be helpful if an assistant pushes the head frombelow or, alternatively, the fetus can be delivered by breech extraction.103

Preterm caesarean section

Physiological studies suggest that cord clamping delayed by 30 seconds in preterminfants, born between 26 and 33 weeks, increases the placental transfer of fetal bloodby 1520 ml/kg. However, when the eects of immediate versus delayed clamping(by 30 seconds) were studied, no significant change in the haematocrit was noted. Theauthors recommend that future studies be done to examine the benefits of delayingclamping for more than 30 seconds.104

Preterm infants (2432 weeks of gestation) in theory benefit from delivery en caul(with an intact sac at the time of delivery) but authors from Leeds observed a relativelyhigh rate of fetal blood loss.105 Maternal blood loss is reported to be more withpreterm caesarean sections.106 In a case-controlled study, caesarean section before 28weeks of gestation was shown to be associated with increased maternal morbidity.107

Techniques for performing caesarean section 37

-

Haemorrhage in caesarean section

The average blood loss at caesarean section is about 0.71.01 litres.59 However, bloodloss is usually underestimated, particularly when this has been large. This has beenshown in a prospective observational study, using the alkaline haematin method,carried out on 40 women at elective caesarean section.108 When the measured bloodloss was less than 500 ml it was estimated with reasonable accuracy, but amounts weresignificantly underestimated when the measured loss exceeded 600 ml.108 Among therisk factors known to be associated with increased blood loss are prolonged labour,second stage caesarean section, placenta praevia, chorioamnionitis, antepartumhaemorrhage, previous postpartum haemorrhage, preterm caesarean section, classicalincision, general anaesthesia and obesity.

Precautions and prevention

A caesarean scar increases the incidence of placenta praevia in subsequentpregnancies.99 At caesarean section for placenta praevia, it is recommended98 that asenior obstetrician and anaesthetist be present in theatre. Patients with placentapraevia need to be informed of the possible complications and the possible need forfurther surgical procedures, including hysterectomy. There should be cross-matchedblood available in theatre before the operation is started.Second-stage caesarean sections need to be performed with caution. Delivering the

fetus in a flexed position using steady traction is important in terms of reducing theblood loss. When the uterine vessels become involved, due to an unintended lateralextension of the incision, the artery needs to be ligated separately. Caution needs tobe exercised when suturing the angle, especially in the presence of excessive bleeding.The bleeding edge may be inverted while inserting a haemostatic suture, hiding thebleeding point from view.

Aetiology and steps of treatment

The commonest cause of haemorrhage is uterine atony and this should be controlled ina systematic way according to standard protocols, with oxytocics, uterine massage andintramuscular injection of prostaglandin F2a (Carboprost) as necessary. Carboprostshould be kept as third-line therapy. A prospective, double-blind, randomized com-parison of prophylactic intramyometrial 15-methyl prostaglandin F2a and intravenousoxytocin in cases of elective sections, showed that routine prostaglandins did not oerany advantage over oxytocin for the control of haemorrhage.109

When haemorrhage continues, the next step is to check for lateral and verticalextensions of the incision and trauma to the uterine vessels. Haemostatic sutures tothe placental bed have been recommended and used successfully.109 Thereafterunilateral or bilateral ligation of the uterine arteries is recommended.110 This sutureshould also include veins, along with a full thickness of myometrium. OLeary and co-workers reported failure with this procedure and a need to resort to hysterectomy inonly 10 cases in a series of 265 patients with uncontrolled haemorrhage.110a A widerknowledge of the procedure of ligation of internal iliac arteries is necessary amongobstetricians, as a lower rate of caesarean hysterectomy has been reported with itsuse.111113 The B-Lynch Brace suturing technique involves a single suture envelopingthe body of the uterus, occluding the blood supply temporarily and allowingstabilization and further assessment of the patient (Figure 9).114

38 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

Blood transfusion

Blood transfusions should not be prescribed without a strong indication, especially asthe majority of the obstetric population in a developed country will compensate forblood loss without compromise to other systems. However, fluid replacement shouldbe adequate and timely. In patients at risk of losing a large volume within minutes,blood should be replaced quickly.115

In a retrospective study over 12 years, which included 1618 women who had acaesarean section, the transfusion rate was 2.4%.116 However, Naef and co-workers, intheir retrospective study of 1610 women delivered by caesarean section, found 103 (6%)to have been transfused. The authors went on to compare the outcome of those whohad been transfused with a matched group of women who had experienced ahaemorrhage but who did not have transfusion. Patients in the transfused groupreceived an average of nearly 4 units of packed red cells (with a range of 1 to 40 units).The mean equilibrated post-operative haematocrit was significantly higher in thesewomen than in the non-transfused group (28.4+5.4% versus 22.7+4.6%: P5 0.0001).Despite this, the hospital stay, post-operative infection and wound complication rateswere similar in the two groups.117

(a) Fallopian tube

Round ligament

Broad ligament

1 6

2 53 44 cm

3 cm

3 cm3 cm

(b)

Fallopian tube

Ligament of ovary

(c)

Figure 9. The B-Lynch Brace suture. (a) Method of B-Lynch suture. (b) Posterior surface of the uterus. (c)The B-Lynch suture after completion.

Techniques for performing caesarean section 39

-

Injuries to urinary and gastrointestinal tract

Surgical injuries to the urinary and the gastrointestinal tract during caesarean sectionare infrequent. However, their recognition and their proper management areimportant in preventing further morbidity.

Bladder injuries

The bladder is at risk of injury in cases of emergency sections, repeat sections, previousabdominal surgery and obstructed labour. Precautions should be taken to drain thebladder before surgery. The surgeon should avoid haste and should open the abdomenin a controlled manner.118 If necessary, the dissection should be carried out with sharpinstruments and the peritoneum should be opened higher up in cases of denseadhesions and in obstructed labour. An adequate bladder flap should be mobilized bysharp dissection in cases of scarring with the lower uterine segment.The reported incidence of bladder injuries varies from 0.0016 to 0.94%. The

incidence was 0.31% in a 5-year study conducted by Eisenkop and co-workers.100 In aseries of 11 284 caesarean sections an incidence of 0.14% was reported and 75% of theseinjuries occurred at the time of emergency caesarean section.23 Inadvertent opening ofthe bladder at the time of caesarean section should be recognized immediately by thepresence of a Foleys catheter in the operating field or by drainage of urine. The extentof the damage should be assessed by noting the location and size of the defect and itsproximity to the trigone and the ureteric orifices. The expertise of a urologist needsto be sought in cases of extensive damage. A simple cystotomy can be closed in twolayers, using absorbable sutures of 2-0 or 3-0 calibre. The mucosa is sutured first andthe submucosa and the muscularis are included in the second layer. The integrity ofthe suturing can be tested with sterile milk or methylene blue dye injected into thebladder. The serosa should be apposed if feasible. Bladder injuries usually heal verywell, but for this the bladder needs to be drained for a minimum period of 710 days.A suprapubic catheter, prophylactic antibiotics and cystourethrogram are not thoughtto be necessary.118 Injury to the bladder at the time of caesarean section does notusually involve the trigone. If any doubt arises, ureteral integrity needs to be checked.Ureteric catheters may need to be used before suturing the bladder.

Ureteric injuries

These injuries are rare, with the reported incidence ranging from 0.02 to 0.05%.92,100a

The majority of ureteric injuries that occur are due to attempts to control bleedingfrom extension of the angle of the uterine incision into the broad ligament. Althoughit is generally believed that the left ureter is more prone to damage because of itsanterior placement (due to the dextro-rotation of the uterus), the studies by Eisenkopand Rajasekar do not support this.These injuries are associated with less morbidity when repaired immediately,

avoiding the need for a second operation. Recognition again is dependent upon thetype and site of the injury. Injuries due to clamping, crushing or kinking of the ureterby a clamp or a suture, not leading to devitalization of the suture, can be reversed byundoing the procedure. Subsequently, urinary function should be checked and aperitoneal drain needs to be left. A urologists opinion should be sought and he/shemay recommend placement of a ureteric catheter via an incision in the bladder.Severe injuries of transection to the distal ureter can lead to devitalization, due to

40 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

devascularization, requiring uretero-neocystotomy. A urologist should be involvedimmediately. Some ureteric injuries are diagnosed only post-natally. Following adicult caesarean section, with a lateral pelvic wall placement of suture to controlhaemorrhage, a high index of suspicion should exist. In such cases, a renal ultrasoundshould be undertaken prior to discharge or if any symptoms of obstruction develop.

Gastrointestinal injuries

Nielson and Hokegard reported an incidence of 0.08% of bowel injury in a series of1319 caesarean sections.119 Bowel is at particular risk of injury in women with previousabdominal surgery for inflammatory bowel disease. Bowel can also be adherent to theprevious scar, or higher on the uterus in cases where myomectomy, closure ofperforation of uterus or previous classical sections have been performed. The bowel isusually injured at the time of entering the peritoneal cavity, or when dissecting thebowel from the uterus for gaining access to make an incision, or when an incisionextends on to the adherent bowel.Bowel injury can be avoided by careful sharp dissection of adherent bowel, avoiding

haste in opening the peritoneal cavity, especially in women who have had previousabdominal surgery, and by employing a vertical incision. Whenever the uterineincision is involved in an extension into the broad ligament, loops of bowel should bekept away while suturing and checking for injury.

Small bowel injury

When an injury to the bowel is suspected or recognized before delivery of the fetus,the area should be marked with a stitch and covered with a moist abdominal pack. Thesite should be inspected for repair after the uterine incision is closed.118

Management depends on the size, depth and number of injuries and the vascularityof the involved segment of the bowel. Small serosal injuries can be left alone. Largerserosal defects should be sutured using 2-0 or 3-0 absorbable or non-absorbablesuture, keeping the suturing line perpendicular to the axis of the bowel. When full-thickness injuries are encountered, either a single-layer or double-layer closure isadvised. A single-layer closure, using a delayed absorbable monofilament, with theknots within the lumen of the bowel, has been shown to allow greater blood flow,decreased inflammation and greater lumen size compared to a double-layerclosure.120,121 An end-to-end anastomosis after resection is required when greaterthan one-half of the circumference of the bowel is involved, or when blood supply iscompromised or when the injuries are over multiple sites. A general or colorectalsurgeons help is essential in managing these injuries. Systemic antibiotics are notusually required. Early feeds with clear fluids are recommended.118

Large bowel injuries

These injuries are managed in the same way as small bowel injuries. Randomizedstudies have shown that penetrating injuries of the large bowel can be managed byprimary closure, regardless of the amount of faecal contamination. A colostomy is nolonger considered necessary for patients with large bowel injury. Drains are notusually necessary, and systemic antibiotics should be started intraoperatively.118

Techniques for performing caesarean section 41

-

CONCLUSION

The safety of caesarean section can be improved by adopting proper basic techniques,combined with evidence based developments covering a number of aspects of care. JoelCohens incision, single-layer closure when feasible, and non-peritonealization arecurrently recommended. This is a field which warrants further research. The CAESARstudy will hopefully answer some questions. Clinicians and patients should beencouraged to participate in current and future research developments. Caution isnecessarywhenever repeat caesarean sections are performed, and there should be earlysenior involvement in complex cases. Anticipation, proper planning and preparation arekey steps in achieving good results.

Acknowledgements

The assistance of the North Staordshire Medical Institute librarians, led by Irene Fenton, isappreciated.We are also grateful to Claire Rigby, Clinical Governance Support Ocer, for preparing this

manuscript, and to Nicola Leighton and Linda Lucking (supported by West Midlands ClinicalTrials Grant) for assistance with reference management.

Practice points

Caesarean section key points. prophylactic antibiotics. Joel Cohens incision. deliver the placenta by continuous cord traction. leave the uterus in for repair. single-layer closure of the uterus, if feasible. no reperitonealizing

Research agenda

. the position of the patient whilst performing the caesarean section to checkwhether lateral tilt is absolutely essential

. whether preoperative antibiotic irrigation of the vagina is helpful in reducingthe incidence of post-operative endometritis and wound infection

. whether prophylactic antibiotics are necessary for elective caesarean sectionswhere the baseline infection rates are very low

. whether exteriorization of the uterus after delivery should be practised

. whether routine swabbing of the uterine cavity after placental delivery isessential

. the best suture material to perform a satisfactory sub-cuticular suture of thewound

42 K. R. Hema and R. Johanson

-

REFERENCES

1. Cotzias C & Fisk N. Patient demand for caesarean section. In Lieberman BA, Shaw RW, Sutton CI &Thomas EJ (eds) Advances in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, pp 916. Oxford: The Medicine Group, 1999.

2. Broadhead TJ & James DK. Worldwide utilization of caesarean section. Fetal and Maternal MedicineReview 1995; 7: 99108.

3. Al-Mufti R, McCarthy A & Fisk NM. Obstetricians personal choice and mode of delivery. Lancet 1996;347: 544.

4. Keeler EB & Brodie M. Economic incentives in the choice between vaginal delivery and Cesareansection. Milbank Quarterly 1993; 71: 365404.

5. Drife J. Maternity services: the Audit Commission Report. British Medical Journal 1997; 314: 844.6. Kirk RM. Surgical Techniques and Technology. In Aljafri AM & Kingsnorth A (eds) Fundamentals of

Surgical Practice, pp 87108. London: Ashford Colour Press, 1998.7. Brown RP. Knotting technique and suture materials. British Journal of Surgery 1992; 79: 399400.8. van Rijssel EJC, Trimbos B & Booster MH. Mechanical performance of square knots and sliding knots in

surgery. A comparative study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1990; 162: 9397.9. van Rijssel EJC, Brand R, Admiraal C et al. Tissue reaction and surgical knots: the eect of suture size,

knot configuration and knot volume. Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1989; 74: 6468.* 10. Rayburn WF & Schwartz WJ. Refinements in performing a Cesarean delivery. Gynecology and Obstetric

Surgery 1996; 51: 445451.11. Lyon JB & Richardson AC. Careful surgical technique can reduce infectious morbidity after Cesarean

section. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1987; 157: 557562.12. Chen FC, von Dehn D, Buscher U et al. Atopy, the use of condoms, and a history of Cesarean delivery:

potential predisposing factors for latex sensitization in pregnant women. American Journal of Obstetricsand Gynecology 1999; 181: 14611464.

13. Doyle M, Alvi I & Johanson RB. The eectiveness of double gloving in obstetrics and gynaecology.British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1992; 99: 8384.

14. Matta H, Thompson AM & Rainy RB. Does wearing two pairs of gloves protect operating theatre stafrom skin contamination. British Medical Journal 1989; 297: 597598.

15. Madar J, Richmond S & Hey E. Surfactant-deficient respiratory distress after elective delivery at term.Acta Paediatrica 1999; 88: 12441248.

16. Smith JR & Gaanh JM. The incidence of glove puncture during caesarean section. Journal of Obstetricsand Gynaecology 1990; 10: 317318.

17. Smith JR & Kitchen VS. Reducing the risk of infections in obstetricians: reducing the risk of needlestickinjury. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1991; 98: 124126.

18. Wilkinson C & Enkin MW. Lateral tilt for caesarean section (Cochrane Review). In The Cochrane Library,Issue 2. Oxford: Update Software, 2000.

19. Matorras R, Tacuri C, Nieto A et al. Lack of benefits of left tilt in emergent Cesarean sections: arandomised study of carditocography, cord acid-base status and other parameters of the mother andthe fetus. Journal of Perinatal Medicine 1998; 26: 284292.

20. Seropian R & Reynolds BM. Wound infections after preoperative depilatory versus razor preparation.American Journal of Surgery 1971; 121: 251254.

* 21. Nygaard IE & Squatrito RC. Abdominal incisions from creation to closure. Gynecology and ObstetricSurgery 1996; 51: 429436.

* 21a. Ellis H. Commentary: midline abdominal incisions. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1984; 91:12.

* 22. Murphy KW. Reducing the complications of caesarean section. In Bonnar J (ed.) Recent Advances inObstetrics and Gynaecology, pp 141152. London: Churchill Livingstone, 1998.

23. Magann EF, Dodson MK, Ray MA et al. Preoperative skin preparation and intraoperative pelvicirrigation: impact on post-Cesarean endometritis and wound infection. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1993;81: 922925.

24. Stark M, Chavkin V, Kupfersztain C et al. Evaluation of combinations of procedures in Cesarean section.International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1995; 48: 273276.

25. Sippo WC, Burghardt A & Gomez AC. Nerve entrapment after Pfannenstiel incision. American Journalof Obstetrics and Gynecology 1987; 157: 420421.

26. Mowat J & Bonnar J. Abdominal wound dehiscence after Cesarean delivery. British Medical Journal 1971;2: 256257.

27. Biswas MM. Why not Pfannenstiels incision? Obstetrics and Gynecology 1973; 41: 303.28. Ellis H & Coleridge-Smith PDJAD. Abdominal incisions vertical or transverse? Postgraduate Medical

Journal 1984; 60: 407410.

Techniques for performing caesarean section 43

-

29. Stark M & Finkel A. Comparison between the Joel Cohen and Pfannenstiel incisions in Cesareansection. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 1994; 53: 121122.

30. Wallin G & Fall O. Modified Joel-Cohen technique for caesarean delivery. British Journal of Obstetrics andGynaecology 1999; 106: 221226.

31. Darj E & Nordstrom ML. The Misgav Ladach method for Cesarean section compared to Pfannenstielmethod. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1999; 78: 3741.

* 32. Holmgren G, Sjoholm L & Stark M. The Misgav Ladach method for Cesarean section: methoddescription. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 1999; 78: 615621.

33. Haeri AD. Comparisons of transverse and vertical skin incision for Cesarean section. South AfricanMedical Journal 1976; 50: 33.

34. Helmkamp BF & Krebs HB. The Maylard incision in gynecologic surgery. American Journal of Obstetricsand Gynecology 1990; 163: 15541557.

35. Ayers JW & Morley GW. Surgical incision for caesarean section. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1987; 70:706711.

36. Finan MA, Mastrogiannis DS & Spellacy WM. The Allis test for Cesarean delivery. American Journal ofObstetrics and Gynecology 1991; 164: 772775.

37. Bowen ML & Charnock FML. Instruments & methods. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994; 83: 476477.38. Hasselgren PO, Hagberg E, Malmer H et al. One instead of two knives for surgical incision. Archives of

Surgery 1984; 199: 917920.39. Jacobs HB. Skin knife deep knife: the ritual and practice of skin incisions. Annals of Surgery 1974; 179:

102104.40. Roettinger W, Edgerton MT, Kurtz LD et al. Role of inoculation site as a determinant of infection in

soft tissue wounds. American Journal of Surgery 1973; 126: 354354.41. Kerr JMM. The technique of Cesarean section, with special reference to the lower uterine segment

incision. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1926; 12: 729734.42. Rodriguez AL, Porter KB & OBrien WR. Blunt versus sharp expansion of the uterine incision in low

segment Cesarean section. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1994; 171: 10221025.43. Boyle JG & Gabbe SG. T and J vertical extensions in low transverse Cesarean births. Obstetrics and