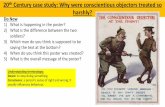

Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

-

Upload

mathew-usf -

Category

Documents

-

view

223 -

download

2

Transcript of Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

1/35

Teachers College Record Volume 113, Number 12, December 2011, pp. 2670–2704Copyright © by Teachers College, Columbia University 0161-4681

Teaching’s Conscientious Objectors:

Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

DORIS A. SANTORO

Bowdoin College

with

LISA MOREHOUSE

Background/Context: Most accounts of teacher attrition fall into one or both of the follow- ing categories: teacher life cycle and workplace conditions. Many educational researchers have described and analyzed teaching in moral and ethical terms. Despite the numerous articles and books that study the personal convictions of teachers, a sustained consideration of how moral and ethical factors may contribute to educators’ decisions to leave the profes-

sion is absent from nearly all the literature on teacher attrition and on the moral life of teach- ing. This article couples these two literatures to highlight the moral and ethical dimensions of teacher attrition through the experiences of 13 experienced and committed former teachers

from high-poverty schools.Purpose/Objective/Research Question/Focus of Study: This study asks: Why do experi- enced and committed teachers in high-poverty schools leave work they love? This article explores how the former teachers in this study weighed the competing calls to teach “right” and their responsibilities to society, the profession, their institutions, their students, and themselves. The participants’ principles, or core beliefs, are analyzed in light of John Dewey’s description of a “moral situation.” Following Dewey, it is shown that in deliberating on their

moral dilemmas, principled leavers ask not only, “What shall I do?” but also “What am I?” Population/Participants/Subjects: The research participants are 13 former teachers from high-poverty schools with tenures ranging from 6 to 27 years of service.Research Design: The study is a philosophical inquiry combined with qualitative analysis of “portraits” of former teachers.

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

2/35

Principled Leavers 2671

Conclusions/Recommendations: This article introduces a category of teacher attrition that is rooted in the moral and ethical aspects of teaching: principled leavers. Akin to conscien- tious objectors who refuse to fight wars they deem unjust, principled leavers resign from

teaching on grounds that they are being asked to engage in practices that they believe are antithetical to good teaching and harmful to students. The category of principled leaver enables teachers to call on a tradition of resigning for moral and ethical reasons rather than viewing their departures as personal failures and the result of individual weakness.Principled leaving, as a category of teacher attrition, provides a vocabulary for such resig- nations and may enable community to arise rather than isolation to prevail. Just as princi-

ples may motivate teachers to enter the profession, principles may provide justification for leaving, even for teachers who envisioned themselves as committed, long-term educators.When experienced teachers who expected to work in high-poverty schools for the “long haul” leave, it should command attention. Policy makers and educational leaders need to attend to the moral and ethical dimensions of teaching when developing pedagogically related poli- cies and in crafting retention efforts.

A sense of what is good and right in professional practice impales someexperienced and committed teachers on the horns of a dilemma: stay and teach in a way that compromises their vision of good work, or leavethe vulnerable populations they serve well? Teachers faced with this pro-fessional impasse encounter moral and ethical questions that test the lim-its of good teaching. Through their dilemmas, these teachers reveal theirabiding commitments to and core beliefs about their work, their stu-dents, and the project of education. This article introduces a category of teacher attrition that is rooted in the moral and ethical aspects of teach-ing: principled leavers. Akin to conscientious objectors who refuse tofight wars they deem unjust, principled leavers resign from teaching ongrounds that they are being asked to engage in practices that they believeare antithetical to good teaching and harmful to students. Just as princi-ples may motivate teachers to enter the profession, principles may pro- vide justification for leaving, even for teachers who envisioned themselvesas committed, long-term educators.

This study looks specifically at how teachers weigh the competingresponsibilities of what they consider good teaching in relation to theirresponsibilities to society, the profession, their institutions, students, andthemselves. Teachers in this study left when accumulated conflictsencroached on their core beliefs about good work, not only specific pol-icy or leadership changes, creating what John Dewey called a “moral sit-uation” (Dewey & Tufts, 1909). Using the term principled leaver does not mean that principles were the sole reason for their leaving or that the for-mer teachers interviewed for this study would necessarily describe them-selves in these terms. Similarly, describing one category of attrition as

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

3/35

2672 Teachers College Record

“principled” does not imply that teachers who leave for other reasons areunprincipled. However, there is something particular to this category of leavers that is distinct from other kinds of attrition described in the liter-ature. The teachers in this study were loath to be simply “successful”teachers.1 Rather, they consistently wove the idea of the good into their visions of teaching. As Sonia Nieto (2009) argued, “Too many teachersare leaving the profession because the ideals that brought them to teach-ing are fast disappearing” (p. 13). This study highlights the content of those ideals and how ideals, or principles, can provide justification forleaving.

WHY DO TEACHERS LEAVE?

Most accounts of teacher attrition fall into one or both of the followingcategories: teacher life cycle and workplace conditions. Beginning withLortie’s (1975) sociological work on the nature of teaching, the profes-sion has always contended with high levels of turnover. In fact, Lortieargued, “teaching was institutionalized as high turnover work during thenineteenth century and the modern occupation bears the mark of earliercircumstance” (p. 15). Lortie’s historical précis serves as a reminder that initially, men served as teachers until they could find better work. When women first gained entry into the work of teaching, it was on the condi-tion that they would leave if they became married. Today, in heterosex-ual couples, women’s work often is viewed as secondary or supplementalincome that is abandoned if the couple has children or if other family caretaking responsibilities take precedence (Borman & Dowling, 2008;Kersaint, Lewis, Potter, & Meisels, 2007). Yet, not all teacher turnovertakes on the mark of past patterns. Moore Johnson and the Project onthe Next Generation of Teachers (2004) have documented the widerrange of options available to women and people of color, thus renderingless attractive the relatively lower salary, lower status work of teaching,especially for those who are academically gifted (Buckley, Schneider, &Shang, 2005).

The “better opportunity” explanation accounts for entry into the pro-fession. In terms of career longevity, Moore Johnson distinguishedbetween long-term and short-term career expectations in the “new gen-eration” of teachers (Moore Johnson & the Project on the Next Generation of Teachers, 2004). Many teachers entering the profession inthe last 10 years, unlike those in previous generations, do not view teach-ing as a lifelong, or even long-term, career. Rather, they see it as anopportunity to do meaningful work before embarking on another careerpath. Teaching may also serve as a change of environment from previous

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

4/35

Principled Leavers 2673

work experiences, following the trend in the United States to change jobsand perhaps career interests several times over the course of a lifetime.Studying graduates from UCLA’s Center X teacher preparation program,Quartz et al. (2008) and Olsen and Anderson (2007) generated greaterspecificity in the language of teacher attrition by noting the subcategoriesof role changers and role shifters, respectively. Olsen and Andersonargued that role shifters should not be simply considered “leavers”because they continue to serve urban youth as principals and teachereducators, and in other positions that enable them to expand theirspheres of influence.

These contemporary analyses of teacher life cycles update and situateHuberman’s (1993) work in the context of U.S. teaching environmentsand policies. However, these studies do not address teachers who, despitetrends of frequent role changing, shifting, or career changes, intendedon teaching for the “long haul” or who had already made shifts to remainin schools in new roles. Huberman highlighted that all teachers tend togo through a “reassessment” phase in which they face some sort of “exis-tential crisis,” typically around years 7–15. Margolis (2008) suggested that the period of reassessment occurs much earlier, perhaps even as soon as4–6 years into teaching. Kukla-Acevedo’s (2009) analysis of the NationalCenter for Education Statistics’ surveys on teacher mobility revealed that first-year teachers leave for reasons distinct from those of their moreexperienced peers. She recommended that research into teacher attri-tion be differentiated based on tenure.

Although folk wisdom suggests that pay is the most significant factor inteacher dissatisfaction and attrition, careful studies show that pay emerges as a significant concern only when other conditions that enableteachers’ success with students are not met (Lobe, Darling-Hammond, &Luczak, 2005; Moore Johnson & Birkeland, 2003; Moore Johnson & theProject on the Next Generation of Teachers, 2004), when teachers feelconstricted by the inability to engage in meaningful ongoing learning(Margolis, 2008), and when the poor quality of school facilities isomnipresent (Buckley et al., 2005). Teachers are more frustrated by alack of collegial interdependence, rigid curriculum mandates, testingthat seems more punishing than problem-solving, and hierarchical deci-sion-making than by low pay.

An absence of a “sense of success” with students seems to contributemost to teachers’ decisions to leave (McLaughlin, 1993; Moore Johnson& Birkeland, 2003; Moore Johnson & the Project on the Next Generationof Teachers, 2004). That lack of efficacy may be due to inadequateteacher education and ongoing professional development, impotent andisolating professional communities, and perceptions of ineffective and

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

5/35

2674 Teachers College Record

unsupportive school leadership. With the advent of No Child Left Behind, a feeling of a “lack of success” with students has become muchmore public and, in some circles, defined in terms of test results. Buckley et al. (2005) suggested that “NCLB itself may be working against improve-ment of the nation’s stock of quality teachers” because of the increasingtime requirements for test preparation and test-taking and the shame of working in schools labeled “in need of improvement” or “failing” (pp.1110–1111).

These studies uncover important changes and ongoing trends inteacher life cycles. They also address certain pressures that weigh onteachers’ sense of success with students and in their professions. Yet, they do not account for why the teachers in this study left even when they wereafforded the hybrid roles of teaching and leadership that Moore Johnsonmentioned as a chief concern for ambitious and well-prepared educators(Moore Johnson & the Project on the Next Generation of Teachers,2004). The teachers studied here left even though they had perseveredin high-poverty schools for 6–27 years. They left despite believing they served their students well, that is, they had a “sense of success.” Lookingat attrition through the lens of the moral and ethical dimensions of teaching can offer a more accurate picture of why these committed, suc-cessful, and experienced teachers left work that they found important and fulfilling.

WHY DOES THE MORAL MATTER?

The moral and ethical aspects of teaching take center stage in this study of committed and experienced teachers who left their work. FollowingHiggins’s (2003) distinction between professional ethics and moral pro-fessionalism, for the purpose of this study, the ethical dimension involvesteachers pursuing the good life in their professional and personalendeavors. In relation to the ethical, teachers might ask, “How is what Iam doing bettering the world or my self?” The moral dimension har-nesses sanctioned and prohibited activities. For instance, teachers might wonder, “Is this approach a good method for teaching my class given what I know about best practices?” The ethical and the moral are oftenintertwined. For instance, violating moral principles (engaging in teach-ing practices that seem wrong to the practitioner) may affect one’s ethi-cal life (the practitioner may sense a diminishment of his or her goodnessas a teacher and person).

In one of the only studies that examine the role of values in teacherattrition, Miech and Elder (1996) investigated the effect of “motivationfor service” on persistence in teaching. They suggested that being an

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

6/35

Principled Leavers 2675

“idealist” or “altruist” can be a liability because of the “uncertain rewards”of teaching. As a result of not having tangible proof of their contributionto society, idealists, Miech and Elder claimed, “do not represent a good‘fit’ with the teaching environment” (p. 239). However, Yee’s (1990) workcontradicts their findings. She explained, “Professional identificationimplies attachment to goals and values as well as active effort; the object of loyalty is to the occupation, not the employing organization—a point pertinent to why teachers stay in the profession” (p. 4). To be a “good fit”teacher, said Yee, values connected to the profession must be present tosustain the work. However, Yee’s study still suggests that “good-fit leavers”resign because of dissatisfaction with their accomplishments with stu-dents (p. 101). How can the role of values in teaching be reconciled inlight of these studies? It seems unreasonable to presume that possessing values in relation to the work can predict attrition. Moreover, it seemsdownright dystopic if we must presume that the teachers who will stay arethose who do not hold ideals about their work.

David Hansen (1995, 2000, 2001a, 2001b) explained that for many teachers, their work is a vocation or calling, one replete with notions of moral and ethical commitments to their practice and the students with whom they work. Others have also shown that morals, values, and princi-ples compose the essence of teaching (Buchmann, 1986; Campbell, 2008;Carr, 2006; De Ruyter & Kole, 2010; Goodlad, Soder, & Sirotnik, 1990; Jackson, 1992; Jackson & Belford, 1965; Lortie, 1975; Margolis & Deuel,2009; Pring, 2001; Purpel, 1999). Despite the numerous articles andbooks that study the personal convictions of teachers, a sustained consid-eration of how moral and ethical reasons may contribute to educators’decisions to leave the profession is absent from nearly all the literature onteacher attrition and on the moral life of teaching. Those studies that consider the moral in lay terms such as “mission” or “altruism” havefocused on early-career teachers (Crocco & Costigan, 2007; Freedman & Appleman, 2009; Ng & Peter, 2010; Stotko, Ingram, & Beaty-O’Ferrall,2007).

This study shows that major dilemmas arise when teachers’ practicefails to align with their vision of good teaching (Crocco & Costigan, 2007;Fenstermacher & Richardson, 2005). What good teaching entails is not simply that teachers are successful with their students, but also that they feel as though they are teaching “right.” Put differently, the moral aspect of teaching involves doing what one thinks is right in terms of one’s stu-dents, the teaching profession, and oneself. This sense of what is right need not be highly personalized or idiosyncratic (Buchmann, 1986);rather, there are senses of what is right integral to most professionaldomains, and teaching is no exception. Fenstermacher and Richardson

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

7/35

2676 Teachers College Record

argued that good teaching depends on morally defensible practices andadheres to the terms of excellence designated by the profession in its log-ical, psychological, and moral elements, as well as the subject beingtaught. Unlike good teaching, there is no necessary moral component tosuccessful teaching. One could be a “successful” teacher of inappropriatematerial, or a “successful” teacher who uses reprehensible methods.

The fact that most teaching takes place within institutions further com-plicates the possibility of good teaching. Darling-Hammond explained,“It is unethical for a teacher to conform to prescribed practices that areultimately harmful to children. Yet that is what teachers are required todo by policies that are pedagogically inappropriate to some or all of theirstudents” (quoted in Colnerud, 2006, p. 377). De Ruyter and Kole (2010)argued that it is beyond the state’s (or other governing body’s) purview to give a substantive account of pedagogical ethics. Institutional man-dates may render teachers’ ethical judgment suspect, and teachers may question the legitimacy of their moral misgivings (Colnerud; Pope,Green, Johnson, & Mitchell, 2009). Colnerud attributed the problem of teachers’ hesitancy in the face of ethical discussion partly to teachers’dual allegiance to their employing institution and to their students, andpartly to teachers’ lack of fluency in moral reasoning and its attendant language. De Ruyter and Kole recommended that teachers be givenschool time to articulate their professional ideals. However, moral andethical pedagogical reasons appear to carry little weight in the current policy environment, at least in the United States. De Ruyter and Kole may provide an explanation for the dearth of moral language in current dis-cussions about teaching: “The more detailed and concrete the [teaching]competencies are defined [by a government agency], the more the moraldimension of teaching is filtered out” (p. 209).

The most sustained consideration of the dilemmas faced by practition-ers who felt as though they were being asked to be “successful” throughmethods they did not think were “right” comes from the field of psychol-ogy. Gardner, Csikszentmihalyi, and Damon (2001) explored what it means to do “good work in difficult times” (p. 5). They show that, faced with a professional crisis (specifically in the realms of genetics and jour-nalism), individuals examine their core values and beliefs about the prac-tice. This process, argued Gardner et al., has the possibility of strengthening the individual’s sense of self as well as clarifying the pur-poses and best practices of a profession. In particular, dilemmas about what constitutes good work require practitioners to examine theirresponsibilities to society, the domain (in this case, the teaching profes-sion), others (especially those they serve), self, and workplace.

This sort of dilemma is captured in part by Sizer’s (1992) Horace

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

8/35

Principled Leavers 2677

Smith, who bemoans his inability to serve students as he believes heshould. Sizer’s fictional composite character struggles with his ideals forthe practice of teaching and a sense of defeat, particularly in the face of what he considers an apathetic and misguided public that sets policy.Gardner et al.’s (2001) study sustains a conversation about competingresponsibilities that takes a more empowered stance on practitioners’sense of what is right and good in relation to their profession. Gardner et al. showed that work, when conducted primarily with the purpose of serv-ing others or contributing to a higher purpose than one’s livelihoodalone, contributes to one’s moral identity.

Some studies have considered morals and ethics in ways that are not connected intimately to teachers’ core beliefs about their practice. Joseph and Efron (1993) studied teachers’ dilemmas by asking direct questions regarding moral conflicts—such as, “Have you ever had amoral conflict with administrators?”—and analyzed the ensuing narra-tives. The authors found that teachers do not categorize conflicts withadministrators as simply differences of opinion, but as moral conflicts (p.12). The authors speculated that the most significant source of moralconflict is when teachers work in communities that hold different normsand values from their own. They wondered if value conflicts could con-tribute to a sense of inefficacy and frustration, yet the value conflicts they described are less about what it means to teach “right” and more about issues such as religion, drugs, and student behavior. Shapira-Lishchinsky and Rosenblatt (2009) analyzed teachers’ perceptions of organizationalethics and found that “when teachers perceive the ethics of their organi-zations as dissatisfying, they may become less committed to their jobs andmay react with dysfunctional work attitudes such as considering leaving”(p. 729). Yet, the ethics that they addressed had little to do with pedagogy or the mission of the school and related more to issues of workplace cli-mate, such as fairness among coworkers.

Intractable dilemmas arise when teachers are asked to engage in prac-tices that run counter to their core beliefs about good teaching. Hatchand Freeman (1988a) described these dilemmas as “philosophy-reality”conflicts (p. 158). They argued that conflicts surface when what teachershave learned to be best practice or developmentally appropriate practiceis at odds with mandated pedagogical methods or curriculum. Hatch andFreeman (1988b) mentioned that these sorts of conflicts alienate teach-ers from their work and could lead to attrition. To attenuate pressures topractice unethically from individual administrators, Helton and Ray (2009) recommended forming ethical alliances with peers. However, thisstrategy may prove impotent when faced with ethical dilemmas posed by district, state, and federal mandates.

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

9/35

2678 Teachers College Record

The language of “philosophy-reality conflicts” will not be used in thisanalysis. Hatch and Freeman (1988a, 1988b) set up philosophy and real-ity as a dichotomy in which philosophy (a term that seems to stand in for what is “good” and “right” practice) indicates a realm separate from “real-ity.” Many teachers in this study did not experience a philosophy-reality conflict for a significant period of their practice. Reality, for several teach-ers in this study, involved what Gardner et al. (2001) called “authenticalignment” (p. 27). For some period, teachers were able to teach in a way that they felt was good and right. Philosophy and reality were not at odds,but existed in negotiated and productive tension.

METHODOLOGY

This qualitative/philosophical study focuses on teachers who worked inhigh-poverty schools. Interviewees responded to an advertisement in aprogressive teacher-oriented periodical or were referred by colleaguesfamiliar with this research project. To be included in the study, intervie- wees had to satisfy all the following criteria: (1) They taught in a high-poverty school where 50% or more of the students received free orreduced-price lunch. (2) They taught for more than 5 years, exceedingthe tenure cited as the time for greatest attrition. (3) They spoke of teaching and their students with fondness and affection in screening con- versations. (4) They did not shift into administrative roles within theirschools or districts. (5) They did not transfer to another school to con-tinue teaching, but left teaching altogether.2 (6) They taught prior to andfollowing the 2001 enactment of No Child Left Behind. The 13 partici-pants represent a range of grade levels, subjects, years of experience, andgeographic areas (see Appendix A). Most came to the profession throughteacher education programs, although some pursued alternate routes totheir certification. For John R., Maggie, Rick, and Susan, teaching was acareer choice pursued after other work experiences and/or family com-mitments.

Following Lightfoot (1983) and Lawrence-Lightfoot and HoffmanDavis (1997), the interviewers posed questions that enabled them toserve as generous interlocutors who simultaneously pushed the partici-pants to clarify, justify, and substantiate their claims (see Appendix B).3 AsLightfoot found, conducting these interviews was revealing for the inter- viewers and for the participants in the study. Reflecting on her work,Lightfoot explained, “For the first time, many of the [interviewees] werebeing asked to reflect upon and think critically about their work, their values and their goals; and as they talked out loud, they discovered how they felt” (p. 371). The participants, by speaking through their experi-

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

10/35

Principled Leavers 2679

ences, often for the first time in a systemic way, gained new perspectiveson their decisions to leave. None of the experienced teachers in thisstudy was asked to participate in an exit interview at his or her school ordistrict upon resignation. For example, Susan taught for 10 years in thesame urban elementary school where she had sent her children and where she had volunteered prior to becoming a teacher. Over the courseof the interview, she came to articulate that her decision was one that involved contradictions in the practice of teaching, and not simply a per-sonal disagreement with enacted policy. She explained, “I would say, if Ilooked back on it, maybe I didn’t know it at the time, but I was becomingincreasingly uneasy about the profession and what was being asked of me.” The researcher’s interest in the moral and ethical dimensions of teacher attrition came into sharper focus as certain lines of follow-upquestions were pursued, and especially in reading, interpreting, and ana-lyzing the transcribed interviews.

Portraiture, as described by Lightfoot (1983), fits well with the praxisof philosophy and qualitative inquiry, especially from a research perspec-tive informed by Deweyan pragmatism and feminist theories. Portraitureeschews dualisms such as “subjective” and “objective,” “reality” and “phi-losophy,” and “personal” and “political.” Portraiture seeks to reveal how subjects make sense of their experiences and to explore aspects of theirlives and experiences that would not be illuminated, save for the por-traitist’s work. Meaning is co-constructed between the portraitist and thesubject of the portrait—and that meaning is mediated by the theoriesthat frame the inquiry. The interplay between qualitative research andphilosophical inquiry brings the abstract to light and enables lived expe-riences to be illuminated in new ways (see Fields & Feinberg, 2001;Garrison & Rud, 2009; Hansen, 1995, 2001a; Jackson, Boostrom, &Hansen, 1993; Knight Abowitz, 2000; Mayo, 2004; Smith, 2001).

The interviews took place between 2006 and 2008, before the height of the current economic crisis in the United States. Most of the intervieweesleft teaching without another job in place, and all the interviewees’ pay was reduced if they moved on to new jobs elsewhere. The bleak unem-ployment picture in the education sector and the rest of the U.S. job mar-ket serves as a stark reminder that leaving one’s work can be a luxury.Future research on moral and value conflicts in teachers’ work will needto look at those who struggle through the dilemmas described here whileremaining in their jobs in schools, in addition to those who leave.

The interviews, or “sittings,” took place at a location of the participant’schoosing and tended to last between 1 1/2 to 2 1/2 hours. The interviews were transcribed and then read several times for repetitive refrains andresonant metaphors (Lawrence-Lightfoot & Hoffman Davis, 1997).

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

11/35

2680 Teachers College Record

These refrains and metaphors led to four broad categories that were usedto code a subset of the transcripts: core beliefs about teaching, value con-flicts with institution/policy, value alignment with institution/policy, andmoral reasoning for leaving. After analyzing the results of initial coding,the categories were simplified to align with the questions arising from themoral and ethical focus of conceptual framework: What does it mean toteach “right”? What are the conditions that lead to teachers’ feeling that they cannot teach “right”? The final three categories that were thenexplored in the complete set of transcripts were: core beliefs about teach-ing, sources of conflict, and moral dilemmas. The former teachers may not have used the language of “moral” or “ethical” in describing theirdilemmas or conflicts, yet their responses were coded as such when theconcern touched on their sense of rightness, goodness, or justice in rela-tion to the work of teaching. This article focuses on the teachers’ corebeliefs about teaching and the dilemmas they faced in weighing compet-ing responsibilities in their profession.

PRINCIPLED LEAVERS

As a result of analyzing these portraits through an ethical and moral lens,a new category to describe certain forms of teacher attrition is necessary. Attention to what constitutes the good in teaching entails engaging withthe moral and ethical dimensions of the work. Although some may cringeat the notion of the moral dimension of teaching, it is important to keepin mind that the moral does not require adherence to a fixed set of dogma or taking on a smug or condescending tone. The moral meanshow we affect others and ourselves for the better and the worse. There isnot a single moment of teaching that cannot be considered moral in thesense that teachers, by virtue of their positions as leaders in the class-room, are enacting and communicating values, often in subtle, indirect ways (De Ruyter & Kole, 2010; Goodlad et al., 1990; Hansen, 2001a,2001b; Jackson et al., 1993).

John Dewey described a moral situation as one in which there is an“incompatibility of ends” (Dewey & Tufts, 1909, p. 207). The dilemmasdescribed by the former teachers in this study are concrete exemplars of Dewey’s philosophical problem; the choices they have to make appeal todistinct goods, each worthwhile—the commitment to good teaching andthe commitment to the well-being of one’s students and/or himself orherself. Ideally, these goals would not be at odds, but when they are per-ceived to be, they have the makings of a moral situation. Dewey posited,“We have alternative ends so heterogeneous that choice has to be made;an end has to be developed out of conflict” (p. 207). This situation is not

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

12/35

Principled Leavers 2681

about cold-blooded calculation. The experience of being in a moral situ-ation can be intensely personal because the incompatible ends can beequally desirable or repugnant. Said Dewey, “This is the question finally at stake in any genuinely moral situation: What shall the agent be ?” (p.210). The choice demanded calls out not only what one in a moral situa-tion should do , but also who he or she is .

Principles do not prescribe particular actions or make choices in moralsituations straightforward. Dewey explained that “the object of moralprinciples is to supply standpoints and methods which will enable theindividual to make for himself an analysis of the elements of good andevil in the particular situation in which he finds himself. No genuinemoral principle prescribes a specific course of action” (Dewey & Tufts,1909, p. 333). Dewey argued for “principles in judging,” and these prin-ciples will serve as tools for analysis in moral situations. Dewey did not argue for principles in “morality” in which good and evil would be deter-mined independent of the context of the situation. Moral situations areexperiences that have the potential to be educative. As a result, one’sprinciples will change as one’s experiences grow. The conflicts experi-enced by the participants in this study provide an opportunity to learnabout the living, dynamic principles that motivate the work of theseteachers.

Principled leavers do not need to proclaim the moral high ground ortout inflexible moral yardsticks that cannot accommodate the complica-tions of everyday professional life in public schools. The principledleavers in this study first compromised the way they believed they shouldteach in order to negotiate ways to teach well within the system and servetheir students. After accommodating their visions of good teaching toremain working with a high-poverty population, they arrived at a junctureat which their work was incompatible with their visions for good teaching, working with students, and their own sense of the good life.

RESPONSIBILITY TO SOCIETY

Elizabeth, who taught for 27 years, articulates succinctly the moraldilemma faced by many of the teachers in this study. After transferring tothree different schools in the last 5 years of her tenure, she came to therealization that her vision of good teaching was incompatible with thepedagogy required in schools in her area that served poor students. Herdecision to leave hinged on the fact that she could not compromise fur-ther her dual commitment to teaching “right” and serving the neediest populations:

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

13/35

2682 Teachers College Record

I knew that I could find a teaching position where I could teachthe way I wanted to teach. And I knew I could find a teachingposition where I was teaching the kids I wanted to teach. But it became more and more evident to me that I couldn’t depend onfinding a position that had both of those things, and I was com-pletely committed to both things: to being with poor kids of color and teaching in a holistic way.

Elizabeth’s statement highlights two core beliefs about her work: She isdedicated to working with a high-poverty population in the publicsphere, and she believes that good teaching involves addressing the whole child.

Only by looking at the core beliefs, or principles, of the teachers in thisstudy can we address how they responded to violations of their commit-ments. Although interviewees were not asked directly to articulate theirbeliefs about good teaching, all of them incorporated statements of core values and principles during the interviews. All the interviewees made it clear that they found teaching in high-poverty schools important andrewarding work and that they saw themselves as serving the population well; that is, they had a “sense of success” for a significant period of time

in their careers (McLaughlin, 1993; Moore Johnson & Birkeland, 2003;Moore Johnson & the Project on the Next Generation of Teachers,2004). For example, Colin, whose work as a debate coach presentedopportunities to work in private schools and who was teaching AdvancedPlacement history and serving as the English Department chair, opted toleave teaching altogether after 6 years because his passion was for work-ing with urban public school students:

Lots of places you could go teach, but if you’re gonna do it, it

seems to me like you should go to the place where it’s most nec-essary. I don’t wanna be some guy in a tweed jacket with thepatches on the elbows pontificating about something that thekids are going to be able to digest and regurgitate and move on.I wanna be someplace where I’ll be able to see significant progress on a basic level . . . that’s why I wanna remain in publiceducation.

Colin’s commitment to working in high-poverty schools signals a moral

commitment, what is right and what should be done, and an ethical vision for himself, an ideal he wants to embody through practice.Stephanie S. found fulfillment and satisfaction in her work as an

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

14/35

Principled Leavers 2683

English teacher and as a team leader of her middle school. Yet, instruc-tional effectiveness was not enough when she had become worn down by what she viewed as anemic or slapdash approaches to teaching andschool policy that neglected students’ needs. She knew that there were“easier” places to teach, but “easy” was not why she taught:

I loved feeling a part of something bigger and better. I think Iknew I was going to do some kind of social change work, andeven though teaching wasn’t paying that well and even though it was really frustrating to me on a lot of levels personally and pro-fessionally, I felt I could go home at night saying I felt good about what I did. [Unlike other teachers who left for a charter school,]I’m gonna stick it out here and do the best I can for these kids,‘cause they don’t have the option to leave.

Stephanie S. also combines the moral and ethical in her reasons forpursuing and remaining in teaching for 9 years. Her view of the moralaspect of teaching issues an injunction that she should not leave theschool for a better environment if the students are not able to make that change. Her ethical development is supported through her participationin something “bigger and better” than her individual commitments.

Tanessalyn, who taught for 10 years, had moved from a rural school inSouth Carolina to work in the city schools in Atlanta. She believed shegenerated resentment from teachers who did not appreciate the highexpectations she set for her students and the ensuing successes they enjoyed.

Here in Atlanta, I taught again in the inner-city schools becauseI found that [was] when I was the most valuable. That’s where I

felt my passion was. So, I got here to Atlanta, got in the inner-city school. Loved it. . . .The new administrator just loved what I wasdoing for the kids. Again, these were kids who had been in trou-ble; they were on their way out of the school . . . but I turnedthem around.

Tanessalyn’s moral commitments involved holding high expectationsfor her students and instilling clear codes of conduct that would gener-ate respect for her class. Her ethical self-image was fed by the success of

students who had previously known failure and disorder.In these excerpts, the teachers speak to a sense of moral and ethical value in their work, alluding to the social responsibility it carries. Othersused terms such as mission (Maggie and Susan) or sacred duty (Rick), and

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

15/35

2684 Teachers College Record

Marney said the work of teaching “comes from a higher authority source.” All the teachers viewed their work as transformative: For Lisa(the contributor to this article), going into teaching was an “activist move,” and John P. spoke of teaching as a “revolutionary act.” Given that they are not freshly minted teachers, they also speak with the understand-ing that they were able to help students acquire the skills necessary tolead empowered lives. They experienced efficacy and pride in their workthat contributed to their ethical selfhood and were able to achieve suc-cess through methods they viewed as moral or “right.”

RESPONSIBILITY TO THE PROFESSION

These educators did not only consider their work service, but they alsofound it to be satisfying intellectually and a source of personal dignity.They believe that teaching is a creative and intellectual endeavor that enabled them to use and hone their talents while contributing to goalsgreater than their own self-satisfaction. At the same time, taking on therole of teacher, they contend, should confer a certain amount of respect.These beliefs emerged when conflicts challenged aspects of their chosenprofession that they had taken to be axiomatic: that the work should beintellectual and creative, that teachers should model lifelong learningand inquiry, and that there should be collaboration and respect amongcolleagues.

Stephanie F. taught core subjects in Spanish for 14 years in an innova-tive language immersion program. Her conception of good teachingrequired that she constantly assess and respond to students’ academicneeds. That aspect of her work became impossible when her school anddistrict adopted mandated curricular materials and fidelity to a regi-mented curriculum sequence.

I just think that I am fundamentally not interested in enactingother people’s plans. There’s no creativity in that. There is noopportunity to use what I know in that situation, and also I thinkit’s a slap in the face to me as a professional. If I can’t use my brain . . . if I can’t have a voice or any ownership, then I don’t seea point [in teaching].

For years, Stephanie F. had found teaching to be an intellectually stim-ulating endeavor that required her to draw on what she knew about sub- jects such as science, her understanding of her students, and herlanguage skills. She viewed the faithful application of uniform curricu-lum to her unique classroom as “not teaching.” Her resistance to the

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

16/35

Principled Leavers 2685

scripted curriculum blended the ethical and moral dimensions of her work. Although her sense of the good life, as accessed by her chosen pro-fession, is obviously diminished, she also indicts the scripted curriculumon moral grounds. She wonders how the script responds to students,their needs, and the unique teaching environment.

Marney taught for 12 years and was baffled by the assumption that she would be motivated to improve her practice if she had to prepare her stu-dents to take a standardized test. Marney was already positioned as alearner of her classroom; interested in her students’ metacognitive skills,she had set tape recorders around the room to listen in on their conver-sations and then used the recordings to show her kindergartners and first graders how they already thought through problems.

I feel like I’ve always been a teacher that’s tried to grow andimprove my skills and learn more about how kids learn and how to teach . . . I feel like as a teacher, I’m someone who has con-stantly tried to learn and read on my own. . . . So the fear about testing did not feel like a healthy fear that would motivate me toget better, because I felt like I was already motivated to get better.

Marney shows that she views teaching right as being a learner of one’sstudents and to be an intrinsically motivated learner. The pressure of test-ing infringed on her desire to help students explore their interests andher well-being as a teacher.

Marney and Stephanie F. articulate core beliefs about teaching—that it should be responsive to students’ needs and interests, that it should be aproduct of what teachers know about their students, that it should befocused on student engagement, questioning, and understanding, ratherthan merely acquisition. In their statements of belief, they also begin tohighlight their moral dilemmas about the profession as they draw paral-lels between the expectations of them as teachers and the messages stu-dents glean about learning. Both Marney and Stephanie see the loss of the creative, intellectual, and responsive aspects of their work as impact-ing their students in negative ways. What they view as good and right inteaching is impinged on by the increasingly standardized curricula, scopeand sequence of teaching topics, and focus on testing. Stephanie haddeveloped original science curricula for her district to align with the stateof Virginia’s Standards of Learning, yet that teacher-developed curricula were scrapped and replaced with textbooks. Marney also was happy toalign her lessons to address Arizona’s Academic Standards. Theirs is not a case of outright resistance to standards or accountability, but a concernabout the larger project of what it means to teach and learn. They found

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

17/35

2686 Teachers College Record

it impossible to do good work when they felt they were sending messagesto students that were antithetical to their core beliefs as they sought toimplement policy mandates.

Budget shortfalls and local politics also impact the sustaining ethicalfeatures of the work. At the beginning of his 10-year teaching career, John P. had attended summer workshops at Harvard on portfolios andauthentic assessment, but the money to support that level of professionaldevelopment dried up. Lisa had built a thriving journalism program and was a new teacher coach, but those responsibilities were eliminatedbecause of funding constraints. However, Lisa also viewed the decision tocut the positions as retribution for being a “squeaky wheel” in her denun-ciation of the school’s reinstatement of tracking. Part of Susan’s decisionto leave involved her losing the student teachers who invigorated herpractice when the local university ended its partnership with her school.Nearly all the teachers mentioned that they were teaching at their best and felt the most positive about the profession when they were involvedin collaborative problem-solving with colleagues and with the support of outside programs such as the Annenberg Foundation, AmeriCorps, theBoston Writing Project, the Bay Area Coalition of Equitable Schools, theCollege Board, and other reform initiatives that involved teachers indeveloping standards, curriculum, and mastery assessments.

School leadership changes affected profoundly many of the teachers inthis study. Former alliances with likeminded principals enabled theteachers’ deviations from scripted curricula because their students wereperforming well. Or, teachers’ special projects were supported becausethey were viewed by administrators as providing an important community service. These experienced teachers viewed new, and often younger, prin-cipals as insecure and having something to prove, or as just merely inef-fectual. The moral and ethical import of these conflicts with school

leadership relates to the dignity of the profession. For Rick, who taught for 11 years, the institution of public schools impinges on the profession-alism of teachers. He explains,

The way we set up our public schools, and I’ve always thought this, but the way we set them up is just cruel, it’s cruel to teach-ers. It says to teachers, “You’re a jerk. You’re kind of a loser. You’re really, you’re just trying to slide out and not do any work,so you need to see 5 classes, and you need to do this, you need

to do that.” And it really doesn’t allow us to be professionals.

For Maggie, who taught for 27 years, the disrespect surfaced at a timeof leadership change.

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

18/35

Principled Leavers 2687

I was just a kind of very active person [on school committees andprojects] and when [the new principal] came in he brought some of his own people and that was difficult. Because you hadto defer to him the things that you had been able to do beforeand you couldn’t do it anymore because it was almost like peopledon’t trust you. Don’t trust you to do the right thing. Maybe they had experience in their [previous] school with deadbeat teach-ers, which happens everywhere. . . . Especially for them to estab-lish their authority as the new principal or the new assistant, they have to kind of take this hard line so that they can get respect. A lot of times they don’t get the respect, they just hear the disdain.

Both Maggie and Rick speak to the presumption that they are “losers”and “deadbeats,” which diminishes the ethical standing of the professionby ascribing to teachers the qualities of incompetence and untrustworthi-ness. A butterfly garden planted at her Newark school in partnership withthe local conservancy and suburban women’s clubs was a point of pridefor Maggie. Without being notified, the organizations were directed tomeet with another teacher. Later, the garden was mowed down at theprincipal’s directive. Such actions motivate the teachers to ask, What doesit say about me if I am part of this profession? Briefly, other examples of what the teachers viewed as professional transgressions were: Tanessalyn,a married woman, was called into the principal’s office and accused of having an affair with a male colleague with whom she was collaborating.Susan approached her principal with a year’s worth of documentation ona student to discuss a possible action plan. The principal suggested that she take the student home to live with her. John P. had been issued a warning regarding the number of Ds and Fs he assigned in his math class.He wrote a letter to the assistant principal requesting a meeting to discuss

strategies for assessing student work, but a meeting was never granted. John R., who taught for 16 years, was told by his principal that he was put on a “growth plan,” but he was never given a copy or informed of the rec-ommendations for growth. Colin resented that on an in-school profes-sional development day, after several hours of no guidance from schoolleadership, teachers were instructed to create midterm exams as an after-thought.

Finally, the teachers resisted the standardization of teaching itself. JohnR. explained that with the emphasis on testing, he couldn’t be a “real

teacher.” Instead, he was rendered a “technician” and argued that withscripted curricula, “anyone could do this.” Noelle also bristled underthe focus of standardization and the accompanying paperwork. She said,“I have knowledge of how kids learn to read, and I saw needs in my

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

19/35

2688 Teachers College Record

building that I couldn’t do anything about because I had to do this grunt work. So, for me, it became a nonintellectual job.” If anyone can do the work of teaching, it no longer provides the ethical sustenance the teach-ers enjoyed for a significant portion of their tenure.

RESPONSIBILITY TO THE INSTITUTION

All the teachers described their work as transformative, using terms suchas liberatory (John P.) and democratic (John R.), and these core beliefsemerged when they resisted what they termed a “factory model” (Rick)of education. They may have viewed their schools as special places wheretheir resistance to the status quo was welcomed, or they understood that tension would be endemic to the work but that, at least in their own class-rooms, they could resist what they viewed as the repressive aspects of schooling. Typically, the teachers compromised their practice in order to fulfill an abiding commitment to working with students in high-poverty public schools. Yet, they reached their limits when they had altered theirpractice to the point of being inconsistent with the principles of teachingthat had kept them in schools: developing strong teacher-student rela-tionships, assessing and addressing students’ learning needs, and engag-ing the community both in and outside the school.

Consistent with their transformative bent, the teachers criticized mod-els of schooling that were based on efficiency and standardization. JohnR. was appalled that the school’s new principal said his management approach was based on the Wal-Mart model. Stephanie S. said that herschool leadership emphasized increasing productivity with fewerresources. She explained that she could not buy into the factory para-digm: “These are students, they’re not woodchips. It’s not a project. It’snot a report. They’re children.” Susan viewed the emphasis on standard-ized testing for first graders a reflection of a “business model they’re try-ing to apply to human beings.”

As the lead teacher in a new small school-within-a-school, Lisadescribed her efforts as “ethical” in ensuring that her team maintainedthe same proportion of special education students and English languagelearners as in the rest of the school. She and her team sought to do right by the students and the school by taking a representative cross-section of the student body and meeting their needs through a collaborativeapproach. After teaching for 12 years, Lisa explained, “There is a tensionbecause doing what I think is right is impossible now , and it used to not be.” With smaller classes and working in a small-school environment, Lisa wasable to track down truant students, work collaboratively to create oppor-tunities to engage resistant learners, and support her commitment to

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

20/35

Principled Leavers 2689

social justice by working in untracked classrooms. In Lisa’s case, she saw her school become tracked, her class sizes double, lessons becomescripted, and opportunities to problem solve and collaborate with hercolleagues evaporate. She explained, “I would not apply for the job that I had the last two years. I wouldn’t apply to teach in a tracked school. I wouldn’t apply to teach 175 students without support for my special edkids. I wouldn’t apply for that.”

Rick also struggled with how his vision of good teaching was under-mined by institutional limitations. Although he taught in a small school- within-a-school, he believed that blanket institutional requirementsthwarted the school’s success and his ability to teach “right.” The wins forthe small school, such as common teacher planning time, came at a highcost that Rick described as “combat fatigue.”

[We were] balancing what we know [are] best practices for mak-ing kids smart with all the requirements of the testing regimesand the gate-keepers that make them dumb. I feel like the assess-ment problems, including the testing regime, and lack of controlof time, is just toxic to good education. [The school is] barely onthe cusp of surviving and getting slaughtered any minute. And Ihate that. Why should I live like that?

Both Lisa and Rick questioned why they should continue teaching inschools that actively thwarted their abilities to teach “right” and servetheir students to the best of their abilities. For Lisa, the situation wasmore frustrating because the school once enabled her to teach “right.”

Noelle, a teacher for 10 years, also longed for the job she was hired ini-tially to perform. Even though she was assured that her position as a leadteacher supporting others in developing their literacy practices would be90% related to instruction, she was spending most of her time placingstickers on test booklets and cataloguing books.

I’d just expended so much energy on things that don’t matterand things that have nothing to do with educating children . . . I want to do the job that I was first hired to do . . . So when I’mmissing it, I’m not missing that job. No one’s letting me do that anymore.

The teachers in this study, who taught prior to and following the enact-ment of No Child Left Behind, argued that teaching had changed for the worse. The far-reaching accountability measures, which in high-poverty schools often take the form of scripted curricula, lock-step scope and

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

21/35

2690 Teachers College Record

sequence of units, and mandated test preparation that narrows the cur-riculum, squeezed out all protected institutional space.

Before resigning, Elizabeth struggled to find a way to remain in teach-ing. Her reaction to the scripted reading program in her district was nomere resistance to change. She wrote to the program’s publisher askingfor research to support approaches that she viewed as miseducative forher students.

I really felt like I had spent a couple of years trying to work withthe system, talking to people about what the most egregiousthings were, trying to figure out how to get around them without doing anything as drastic as we did [publicly voicing oppositionto a scripted reading program]. I really felt like I’d done my best to do that, so for me, I felt like I had three options at that point.I could quit, I could shut my door and do my own thing and stay out of the fray, or I could stand up for what I thought was impor-tant for children.

Like Elizabeth, Stephanie F. took a stand for her moral convictions. Sheand a group of colleagues attempted to empower parents to resist nar-rowed curricula and standardized testing. They also wrote letters to theeditor of the Washington Post :

For a long time, we thought that where we could change [theschool system] was in our own classrooms. . . . No matter what came down from above, if we closed our doors and we did what we believed was right, we could go forward. But that turned out not to be the case because what started to come down fromabove just got worse and worse and worse, and the pressurebecame so great that there was no way around it. And I thinkthat’s the most insidious part of it—the idea that if you haven’t prepared your kids for all of this, that you’re putting them in abad place.

Stephanie F. worried that by capitulating to her district’s directives tofocus primarily on testing, she would be complicit in harming children.However, she also points to the paradox that by refusing to engage inpractices that she believed were not conducive to good teaching (such asteaching to the test), she likewise could be accused of harming her students.

Elizabeth and Stephanie F.’s experiences highlight three strategies that most of the teachers in this study attempted to employ, if possible. They

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

22/35

Principled Leavers 2691

spoke up about what they saw students needing and why they felt students’needs were not being met, they attempted to work within the expectationsset by their schools and districts, and finally, they left. It is possible that theclassroom door is no longer the impermeable membrane that isolates(and also protects) teachers and their work. Even behind “closed doors,”the teachers in this study found it impossible to pursue their visions of good work in the current pedagogical policy environment.

RESPONSIBILITY TO STUDENTS

For the teachers represented in this study, no one event or policy cat-alyzed their decision to leave. Rather, they ceased to feel joy at work,found themselves consistently impatient, or sensed, as Rick put it, “theedges of burnout.” In assessing their current practice, they found that they no longer recognized their teaching selves, and they did not like what they saw. By compromising and being willing to adjust their practicein order to comply with relatively small and gradual external demands,they eventually were teaching in a way that was inconsistent with their vision of good work.

Lisa told her class that she would not be returning the following yearby explaining to the students that they deserved more than she was ableto offer.

I said, “You know that teacher who you kind of feel like shouldhave left a long time ago because they aren’t really in it and they get mad all the time and you kind of feel like they should just step back a few years ago?” And they’re like, “Oh, yeah!” and they were all trying to name them. You know? [Laughs] They all wanted to say, “Yeah, so and so, she really should have left.” AndI said, “Well I don’t want to be that person and I’m not that right now, but I kind of feel it and so I want to step back before I’mthat person.”

Self-described as a “rebellious believer in kids,” Lisa knew she had tomake a change when she sensed she was giving up on students she wouldhave normally done everything in her power to reach. Colin also basedhis decision to leave in part on the fact that he was losing patience withstudents. He explained, “I felt, I feel like I worked up until the last day at seeing students progress. And that’s the other reason why I had to go.”He did not want to have on his conscience that he did not teach to thebest of his ability, and so he left midyear.

Colin’s decision was not without consequence. He became “physically

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

23/35

2692 Teachers College Record

sick to [his] stomach” when passing by the school after he resignedbecause he was aware that, in all likelihood, the students were now beingtaught by someone less qualified and less effective than he. Many of theteachers mentioned that their students were exceeding state goals(Tanessalyn) or performing higher than average for their district (Lisa).The moral dimension of these teachers leaving is that they base theirdecisions not on the fact that they were ineffective; rather, they decidedto leave because of their convictions regarding the standards of practicethat they ought to uphold and they believe the students deserve. Theteachers in this study opted to exit the classroom rather than participatein practices or adopt attitudes that would violate what they viewed asright, just, and good for students.

Marney felt that she spent more time documenting what she was sup-posed to be doing in her classroom than addressing the standards as shefelt she always had prior to receiving policy directives. Most significantly,she no longer found that her work positioned her as an advocate for children:

I decided I wasn’t going to teach anymore because I feel like that is what the state or the nation is defining education in this way. And that is totally opposite of what I think it should be, youknow? And so, it’s time for me not to do it anymore . . . I almost feel like, in a way, I’m oppressing them. I’m oppressing the kids.

John R.’s background as a factory worker-turned-teacher fueled hisdrive for education to contribute to social justice. He lamented that teaching no longer was a way for him to work for liberation:

I think we should be educating our kids to make history—tochange the circumstances of their lives. That’s what we’re therefor. That’s what America is about. And now they’re going to turn[education] into this sort of, “Sit down, shut up, stand up, dothis, walk over here.” Come on. That’s not [teaching]. I don’t know if there’s a place for me in that set-up anymore.

Many of the teachers in this study echoed John R.’s sentiment: “I don’t know if there’s a place for me” in teaching. These teachers did not leavebecause they were incapable of doing the work or disliked the work (at least as they once knew it). They left because they did not see the workthat they were currently doing as fitting into their definitions of goodteaching. Current policy constructions of “teacher” did not align withtheir professional self-image.

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

24/35

Principled Leavers 2693

Noelle explained that she had to leave teaching because her continuedpresence at the school signaled complicity with the district’s mandates forhigh-stakes testing and teacher-centered curriculum:

I don’t believe in any of this. I can’t be a part of any of this if youare doing wrong by children. It’s sort of like, being involved istacit approval for something that I fundamentally disagree with. . . I think that’s in my core; that’s what I believe.

Maggie also spoke of high-stakes testing as traumatizing the newcomersto English whom she taught. She felt that inflicting such pain was anti-

thetical to her role as an ESL teacher. Susan pushed back against theexpectations for standardized testing for her first-grade students andrefused to have 6-year-olds take an exam for 2 1/2 hours with no breaks:

I left the woman who was delivering the [test] books in my roomand I said, “I have to go talk to the principal about this.” And I just walked down to her office and I said, “I’m not going to dothis. My assessment as a teacher of the students in my room . . .”I said, “If I’m going to ask them to do this, I have to do it in con-

ditions that I think are going to be the least offensive to their sen-sibilities.” And, umm, she said that she couldn’t allow that. AndI said, “Well, that is what I’m going to do, and I guess we’re goingto have to talk about consequences later.”

Despite Susan’s willingness to challenge practices she deemed wrongand harmful to students and to voice her concerns with school and dis-trict leadership, she could not brook the onslaught of curricular andassessment requirements. By the time she left, first graders were expected

to take 28 formal written assessments over the course of the school year,and she was unwilling to serve as a willing party in those practices.The teachers refused to teach in ways they believed were harmful to

children, whether due to policy requirements or their own demoraliza-tion in the face of the overwhelming conflicts and dilemmas presentedby the work. They found practices expected by their school leaders andarticulated in educational policy unrecognizable in relation to their visions of good education and teaching “right.” When Elizabeth’s princi-pal asked her why she might not return to teach, she responded, “[The

school has] completely changed from a place that is engaged in educat-ing kids to a place that’s engaged in instructing and testing kids.” As aconsequence of the changes that altered teachers’ relations to students,

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

25/35

2694 Teachers College Record

they no longer recognized themselves in the role of teacher within theirschool environments.

RESPONSIBILITY TO SELF

Returning briefly to Dewey’s description of a “moral situation,” what iscalled forth is the self. The questions that one must respond to are not only “What shall I do?” but also “What shall I be?” And the self faces aquestion in which choosing between the conflicting possibilities can beamenable or despicable in equal measure. In the case of all the teachersin this study, at some point, they faced the dilemma: stay and serve thestudents, or leave and preserve oneself? What makes this predicamenta true dilemma is that teaching students well had been a source ofmoral and ethical sustenance for their selves that became increasingly inaccessible.

John P. described his teaching as having “an untenable intensity.” Hedescribes the pressures of working in a high-poverty school and theintense energy necessary to work with resistant students as sapping hisability to harness the ethical dimensions of the work.

I need to have joy and I need to have creativity . . . my experienceof being a teacher ceased to be fun, joyful, or creative. And it kind of only remained meaningful and right. But, but that, but meaningful and right and correct weren’t sustainable. I neverchecked out in front of the students. But it was just . . . I was on vapors.

John P. acknowledged that the moral legitimacy of teaching (it was“meaningful and right”) is still present, albeit diminished. However, he

could not sustain his ethical responsibility to himself while meeting what he saw as the moral demands of the work. Significant to John P., and asmentioned by Rick, Lisa, and Colin earlier, was that he maintained hishigh expectations for teaching students up until the time he left ratherthan remain and occupy the role of “burnt-out” teacher.

The teachers cared a great deal about maintaining their personal andprofessional integrity. Susan explained that her school’s insistence onuniformity, the increasing demands on her work with fewer resources,and the lack of support from new school leaders made her realize that

she could not do the work any longer.

It was demoralizing on a personal level and a professionallevel. And the scripted-ness, the insistence on the same kind of

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

26/35

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

27/35

2696 Teachers College Record

of them led to professional misrecognition and, ultimately, resignation. Without a doubt, disagreements over policy mandates, curricular

choices, assessment requirements, and leadership styles factored intothese teachers’ reasons for leaving. However, when placed in relation tothe teachers’ core beliefs, the significance of these sometimes minor, andsometimes sweeping, changes takes on a moral and ethical tenor. Only by approaching teachers’ reasoning through a moral and ethical lens do wego beyond theories of accommodation and resistance or explanationsthat hinge on fitness for the task of teaching in high-poverty schools.Clark (1990) explained,

Overarching principles have been agreed on in our society and within the teaching profession—principles dealing with honesty,fairness, protection of the weak, and respect for all people. Thereal work of teaching, morally speaking, is carried out when ateacher rigorously struggles to decide how best to act in relationto these general principles. Just as teacher decision making inintellectual and pedagogical matters has been shown to be at theheart of professional teaching, so too is decision making in themoral domain (p. 252)

This decision-making can extend not only to how to conduct oneself while teaching, but also to whether to continue teaching at all.

PRINCIPLES IN POLICY MAKING AND RETENTION EFFORTS

Conscientious objectors to military service may feel isolated at the timeof their decisions, but they may also reference a history and tradition of refusing to serve on moral and ethical grounds. Teaching’s conscientiousobjectors need to be recognized as such. Distinct from conscientiousobjectors of military service, who refuse to engage in activities that may lead to killing others, teaching’s conscientious objectors refuse to partic-ipate in practices that harm students and diminish the profession.

Looking only at the outward reasons the teachers in this study decidedto leave their work offers a well-worn picture of teacher attrition—con-flicts with administrators, dissatisfaction with the work environment,resistance to policies that affect classroom practice. Yet, taken in light of the moral situation as described by Dewey, these sorts of conflicts reflect a deeper problem. The dilemmas these teachers face are moral becausethe heterogeneous ends are equally repugnant. Lisa captured the conun-drum succinctly: “This choice: do work that’s important, and fade out,right? Or take care of yourself and feel empty. What a [expletive]

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

28/35

Principled Leavers 2697

decision that is.” Looking only at teachers’ sources of conflict, indepen-dent of their core beliefs, might make their reasoning seem petty or idio-syncratic. These sources of conflict take on greater significance whentaken in consideration with their core beliefs about teaching and learn-ing. They take on moral and ethical weight when placed in dialogue withthe questions, What is good? What is right? What is just?

When teachers’ work is invested with moral and ethical import, thereis a personal toll in resigning. Nearly all the teachers interviewed for thisproject spoke of “recovering” from the process of leaving. Maggie taught for 27 years and still aches from her decision to leave the inner-city schools where she worked throughout her career.

This feels like a personal failure. We’re kind of looked at, asteachers are, like we are in the noble profession. [People say],“You’re doing such wonderful things” and “Schools need peoplelike you.” And when you feel like you can’t live up to the expec-tations or you can’t deal with the stress level or can’t deal withpeople constantly expecting more and more of you because youare a good teacher. Then, if you kind of buckle under this stress, you feel like you’re a personal failure, and that you can’t do yourservice. You can’t, you can’t fulfill the mission that you wanted tofulfill when you became a teacher.

The category of principled leaver enables teachers such as Maggie andthe others in this study to call on a tradition of resigning for moral andethical reasons rather than viewing their departures as personal failuresand the result of individual weakness. Principled leaving as a category of teacher attrition provides a vocabulary for such resignations and may enable community to arise rather than isolation to prevail.

Certain kinds of teacher attrition should be given greater attention. When experienced teachers who expected to work in high-poverty schools for the “long haul” leave, it should command attention, at the very least, at the school and district levels. The costs borne by high-turnover schools (which tend to be high-poverty schools) are high(Allensworth, Ponisciak, & Mazzeo, 2009). Borman and Dowling (2008)and Lobe et al. (2005) illuminated the problem from an organizationalperspective. Losing experienced teachers results in weakened collectiveknowledge; a drain on school finances in terms of recruiting, hiring, andretraining; a lack of mentors; repetitive professional development that consistently attempts to “catch up” new hires and frustrates experiencedteachers; and shame for experienced teachers who remain (Lobe et al.).Few schools and school districts require or recommend exit interviews

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

29/35

2698 Teachers College Record

for teachers who resign. Comprehensive data on teachers who leave theprofession are even more difficult to find. Kersaint et al. (2007)explained, “Ideally, one would identify teachers most likely to resign while they are still teaching, and then meet their needs” (p. 786). Yet, without an understanding of what precipitated the leave-taking of thoseteachers whom schools would hope to keep, there is little guiding thiskind of preventive work. Quartz et al. (2008) highlighted the costs of teachers moving into nonteaching professional roles on their schools andtheir students, even considering that the former teachers were still work-ing within the school system. They explained, “Policy makers currently struggle with how best to sanction or encourage attrition among ‘bad’

teachers, yet there is virtually no attention paid to all the ways that theeducational system sanctions attrition of the nation’s most well-preparedteachers” (p. 245, see also Coggshall & Ott, 2010). In the case of high-poverty schools, the concern should be even more urgent. It has been well documented that schools with poor populations and students whofall into the many of the disaggregated subgroups that need to show progress each year under No Child Left Behind (English language learn-ers, poor students, Black and Latino students, special education stu-dents) feel the effects of wide-sweeping policy mandates in more

Draconian forms—relentless test preparation, scripted curriculum, andpublic shaming.

Further research into the causes and conditions of experienced-teacher attrition in high-poverty schools needs to be conducted. Gardneret al. (2001) explained, “When a professional realm loses some its most thoughtful people because of constraints that they see as endemic, it has ventured into dangerous territory” (p. 141). The conflicting responsibil-ities described here point to a larger concern regarding how teachersretain integrity in their work. The conflicts the teachers experienced

were symptoms of a larger concern: Am I doing good work? Am I livinga good life? Ultimately, these teachers responded in the negative and left. As John P. explained, “All jobs have contradictions . . . teaching is not spe-cial, but deeper.” His point is confirmed by Ng and Peter (2010), whofound that “psychic rewards” are the most significant reason for pursuingteaching and remaining in the profession (see also Stotko et al., 2007).

Attention to the moral and ethical dimensions of teaching is necessary,but not sufficient. Material conditions must support, or at least not sub-stantially hinder, teachers’ visions of good work. Marilyn Cochran-Smith(2004) recognized the limits of moral commitments. She explained,“Good teachers are still lovers and dreamers. . . . But these reasons arenot enough to sustain teachers’ work over the long haul . . . teachers

-

8/18/2019 Teaching's Conscientious Objectors Principled Leavers of High-Poverty Schools

30/35

Principled Leavers 2699

need school conditions where they are successful and supported”(p. 391). Similarly, Fenstermacher and Richardson (2005) explained that the onus of good teaching cannot fall solely on the educator. Good teach-ing requires an environment in which doing good work can take place.The findings of the Retaining Teacher Talent study

consistently indicate that to retain more teachers of all genera-tions, the most powerful thing that policymakers and others cando is to support teachers’ ability to be effective with their stu-dents. Teachers who can see that they are making a difference intheir students’ learning will stay in the profession longer.(Coggshall, Ott, Behrstock, & Lasagna, 2010)