Syringomyelia

-

Upload

liew-boon-seng -

Category

Health & Medicine

-

view

4.901 -

download

1

Transcript of Syringomyelia

Syringomyelia

29-8-2006

BS LIEW

Outline

• INTRODUCTION

• PATHOGENESIS

• PATHOLOGY OF SYRINGOMYELIA

• CLASSIFICATION

• CLINICAL FEATURES

• NATURAL HISTORY

INTRODUCTION

• Syringomyelia is a condition characterized by the formation and enlargement of fluid filled cavities within the spinal cord

• Ollivier d'Angers (1827 ) introduced the term syringomyelia, to describe pathological dilatation of the central canal, after the Greek συριγξ (syrinx), meaning pipe, tube, or channel and μυελος (myelos), meaning marrow

INTRODUCTION

• Stillings in 1856, used hydromyelia to describe a dilatation of the central canal, and syringomyelia referred to a cystic cavity separate from the central canal.

• To avoid confusion, syringohydromyelia and hydrosyringomyelia have been used to encompass all syrinxes.

• Other terms used include progressive posttraumatic cystic myelopathy for post-traumatic syrinxes, and pseudosyringomyelia for cysts occurring in association with tumours, haemorrhage, or necrosis.

INTRODUCTION

• In 1891, Chiari’s description of cerebellar malformations included two types (I and II) that were associated with syringomyelia.

• In the Chiari type I malformation, 57–65% of patients will develop syringomyelia

INTRODUCTION

• Syringomyelia occurs in association with a wide array of congenital and acquired conditions

• Most cases are associated with an abnormality at the craniocervical junction or a localized spinal abnormality.

INTRODUCTION

• Syrinxes develop in 35% of patients with occult spinal dysraphism, 37–53% of patients with diastematomyelia, and 24% of patients with a tethered cord

• Syringomyelia may be seen with virtually any intramedullary tumour

INTRODUCTION

• Two thirds of patients with haemangioblastomas and half those with spinal ependymomas have an associated syrinx

• Syringomyelia in association with an extramedullary mass is not common but may be seen with neoplasms, cysts, lipomas, cervical disc disease, or spondylosis

• Non-traumatic arachnoiditis of the posterior fossa or spine may be associated with syringomyelia

INTRODUCTION

• Syringomyelia affects mainly children and young adults, presenting on average before the 29th year

• In patients suffering a spinal injury (between one and thirty years after injury) , 21–28% of them will be found to have a syrinx and 30–50% will have a degree of spinal cord cystic change

• However, symptomatic syringomyelia is reported in only 1–9% of the spinal injury population

PATHOGENESIS

• 3 primary theories:– Dysraphic theory

• A defect in neural tube closure predisposes the development of a syrinx

– Hydrodynamic theory• A disturbance of CSF outflow from the third ventricle, a “pre-

syrinx” condition associated with alteration of CSF flow and Valsalva contribution to syrinx expansion

– Degeneration theory• Disturbed blood supply, blockage of perivascular spaces,

microhemorrhage with tissue atrophy (autolysis) and physical tissue compromise

PATHOLOGY OF SYRINGOMYELIA

• Syrinxes most commonly occur in the low cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord

• The syrinx wall is formed by compressed glial tissue surrounded by gliosis

• There is evidence of Wallerian degeneration, macrophage infiltration, demyelination in the surrounding white matter, and central chromatolysis and neuronophagia in the grey matter

PATHOLOGY OF SYRINGOMYELIA

• Enlargement of perivascular spaces may be present.

• Vascular changes may be seen around the syrinx, including hyalinized and thickened vessels, oedema, and haemorrhages.

• Syrinx enlargement often affects the crossing spinothalamic tracts.

PATHOLOGY OF SYRINGOMYELIA

• Arachnoiditis, or spinal leptomeningeal inflammation and thickening, is often found in conjunction with post-traumatic syringomyelia.

• In these cases the dura is firmly affixed to the underlying spinal cord due to a proliferation of collagen in the subarachnoid compartment.

• The collagen may form a thick layer embedding the damaged spinal cord remnants, and entrapping nerve roots and vessels.

• There is some neovascularisation, osseous metaplasia may occur.

CLASSIFICATION

• Milhorat et al. have classified syrinxes according to pathological and MRI features into:

d) atrophic cavitations; and e) neoplastic

CLINICAL FEATURES

• The first clinical correlation was made by Portal (1804) recognized that progressive sensory loss and paralysis of the limbs of a servant was associated with post-mortem findings of cystic spinal cord cavitation.

• Schultze (1882) described the classic dissociated sensory syndrome of pain and temperature loss with preservation of light touch and proprioception

• Symptomatic progression is usually gradual.

CLINICAL FEATURES

• The commonest initial symptoms include segmental pain and sensory loss

• Pain is dull, aching, or burning in nature, reflecting injury to spinothalamic pathways

• Compromise of crossing fibers of the spinothalamic tract is one of the earliest clinical features of central cord cavitation.

• The pain is often at or above the level of injury, and may be mild or severe, constant or intermittent

• Coughing, sneezing, straining, or sitting can exacerbate the pain

CLINICAL FEATURES

• Dissociated sensory loss in ascending segments is more common than complete loss of sensation

• Progressive asymmetrical weakness tends to occur after the onset of sensory symptoms

• Patients will generally report a gradual loss of motor function above the level of previous injury.

CLINICAL FEATURES

• There is also evidence that spasticity is worse in spinal cord injury patients with a syrinx than in those without syrinxes

• Other associated symptoms and signs include asymmetrical reduction in reflexes, hyperhydrosis, autonomic dysreflexia, Horner’s syndrome, dysphagia, and cardiorespiratory dysfunction

CLINICAL FEATURES

• In rare cases, the syrinx can extend into the brain stem and cause bulbar symptoms and signs

• Progressive intramedullary cavity expansion can lead to compromise of the anterior horn cell region, resulting in a lower motor neuron presentation in the upper extremity.

• Lateral expansion resulting in corticospinalk tract compromise leads to varying degrees of lower extremity spastic paraparesis

CLINICAL FEATURES

• Dysautonomia may occr secondary to compromise of sympathetic fibers

• Neurogenic arthropathies are seen in the older individual.

• Cauda equina syndrome may be the only presentation in patients with cavitation primarily in conus medullaris

Dr Patrick SchwederDepartment of Paediatric NeurosurgeryStarship National Children’s Hospital

Auckland, New Zealand

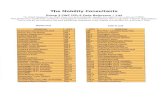

Presenting Features

10 years experience in the management of syringomyelia in the paediatric population

(180 patients)

Presenting Features

10 years experience in the management of syringomyelia in the paediatric population

(180 patients)

Dr Patrick SchwederDepartment of Paediatric NeurosurgeryStarship National Children’s Hospital

Auckland, New Zealand

NATURAL HISTORY

• The natural history of syringomyelia is not well established

• Symptoms may progress for a few years and then remain static, or there may be a slow and intermittent or continuous deterioration

• Most patients demonstrate slow progression of symptoms and signs

• A few progress more rapidly, sometimes immediately after myelography or from haemorrhage into the syrinx from vessels in the wall of the cavity

• In small observational series, 17%–50% of patients remained static without treatment over 10 years or more

• There are reports of spontaneous resolution in adults and children, which may be due to decompression of the syrinx into the subarachnoid space

NATURAL HISTORY

Thank You