Susan Bassnett-McGuire - An Introduction to Theatre Semiotics

-

Upload

eyluel-f-akinci -

Category

Documents

-

view

159 -

download

4

description

Transcript of Susan Bassnett-McGuire - An Introduction to Theatre Semiotics

I

l

i.

1

I

Edited by Simon Trussler

CLARE VENABLES

LAURENCE SENELICK

BILL MARTIN

JAN KOTT

TONY HOWARD

SUSAN BASSNETT-McGUIRE

THEATRE QUARTERLY published in association with the University of East Anglia

Vol. X No. 38 Summer 1980

Managing Editor: Michel Julian

Associate Editor: Clive Barker

Editorial Assistants: Malcolm Hay, Irene Staunton

Advisory Editors: Arthur Ballet, C.W.E. Bigsby, Edward Bond, Katharine Brisbane, Robert Brustein, Christophe Campos, Martin Esslin, William Gaskill, John Harrop, Nicholas Hem, Bamet Kellman, Jan Kott, James W. McFarlane, Erika Munk, Alan Schneider, John Willett

Contents

3 The Woman Director in the Theatre why have women found directing the least accessible branch of the profession?

8 Russian Serf Theatre and the Early Years of Mikhail Shchepkin a unique sort of slavery ~ and a naturalistic epiphany

17 Diary of a Playwriting Bursary two places, two projects, one writer in residence

27 After Grotowski: the End of the Impossible Theatre what lessonsfrom 1968for the generation of 1980?

33 Theatre of Urban Renewal: the Uncomfortable Case of Covent Garden has theatre helped or hindered in the battle against 'redevelopment'?

47 An Introduction to Theatre Semiotics finding a new language for the 'language' of theatre

I ANTHONY ACKERMAN 55 Sater, and the Rise of Political Theatre in Holland

CECIL W_ DAVIES

the development of a socz"ally-consciow theatre, and the evolution of a pioneering group

68 Working Class Theatre in the Weimar Republic, 1919-1933: Part I detalled background to a period of creative ferment

Theatre Quarterly is published in March, june, September, and December by TQ Publzcations, 31 Shelton Street, London WC2H 9HT, England ISSN 0049-3600

1972).

:m and

tres of

urna/ 'Ne~

10.

::Ovem [{XII,

were ding. Plan

•dilly ming .nedy

'Pori no),

771. one was and ness ;ave

J.

ber

:tet

nt

susan Bassnett-McGuire

An Introduction to Theatre Semiotics To many theatre people, the language of semiotics zs merely mystifying, and all too often the {I w English-speakz'ng workers z·n the disczphne appear even to relzsh the inaccessz'bz'lz'ty of their o~n jargon. Yet the study of how meaning can be expresse~ through szgns, gesture, and expression, as well as through words, should he of enormous zmportance to the lwe theatre, which has so often suffered from the inabz'hty of even z'ts best crz'tics to jz'nd a 'vocabulary' in which to discuss other than the textual aspects of a production. Susan Bassnett-McGuz're, who teaches z'n the Graduate School of Comparative Literature in the University of Warwick, here dz5cusses the use of semiotics as zt effects theatre workers and students, by way of introduction to a fuller development of the subject z·n future zssues - planned to include contrz.butions from such prominent semioticians as Patrice Pavzs and Kier Elam. Susan Bassnett-McGuire 5 own study of translation theory wdl be publz5hed next year by Methuen, and she zs also currently co-ordinating a major feature on translation for the theatre, scheduled for TQ40.

THE INCREASING number of English translations of European work in theatre semiotics is testimony to the growing British and American interest in this type of work. Later this year. the first monograph by a British scholar. Keir Elam, will be published by Methuen in the New Accents series under the title Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. It seems a propitious moment at which to begin discussion of theatre semiotics in the pages of Tit eat re Quarterly.

A short time ago it was fashionable. whenever the term sernlotlo or semiology was used. for sceptics pointedly to ask what it meant. And in discussing developments in semiotics. there is still a tendency to refer nervously back to the pioneering statement of Ferdinand de Saussure, who proposed the notion of a

'science of signs· .1 Huwnn. it is not within th~ scope of this article either to give an acount of the historical development of th~ discipline or to try and defend it against those who might dismiss new dis~:iplines as so much 'jargon'. The purpose here. and in the snies of further artides that will be appearing in this journal. is to try and suggest ways in which the now well established discipline of theatre semiotics can be useful to those in the English·spcaking world who are engaged in the discussion of theatre.

Play, Text, and Performance Traditionallv. discussion of theatrP has been polari1t>d along lines of binary opposition: written text cer.vus performatHT, Sl holars r·,·rsus pra< titioncrs. historians versus rc\iewcrs. :\or ha1e attt·rnpts to bind the divisiom to,<;t'thcr been succt>ssful since the tt'nns on which the binding proces<> is undenakt•n are llften the same as <hose that initial!~· lt·d to tllf' split In the case of att•·n•ph 1,, litt·r df\ '<hoi us t<l stud\ tt':\ls in perlot'tld!lll'. lor 1'.\ampir iris ,,ftcn suted that a pia)

onlv ·Jr'"'' '·'hen _,c:T!l on a stage Yet 1 rtttLs and

reviewers are the first to insist on the purity of the written text, on the need for directors and actors to somehow remain faithful to that text: in short, the written text acquires an authority m•er the authority of those actually performing it. With traditionally 'sacred' texts. such as the plays of Shakespeare. the purity of the written text assumes an almost metaphysical value.

Yet. as any historian of theatre knows. those written texts were by no means absolute in Shakespear-e's own lifetime. Moreover. as any theatre practitioner knows. the shape of the play is not predetermined by the omnipotent author's pen. it emerges from the combination of such factors as the availability of actors. the size and shape of the playing space, the technical apparatus required, the financial exigencies of the tim<". and so on. Shakespeare ·· like Racine, another supposedly 'sacred' author - was first and foremost a theatre practitioner. someone who understood the practical problems of making a play as well as the efficacy of patterns of car~fully structured images and metaphors in a literary text.

Yet even if we reject tht> practice of reading a playt~xt as if it were a piece of literature, with no regard for its performance dimension, the next step does not take us much further. If the critic insists that !In mid can only b<' fully realized in pt>rformance. isn't thC' stress still on the predominance of the written text d~ a pn."-/Jerfonnance structure? ~1any critics, cntainlv. arc convinced that the function of performance is ro illu:tratc aspnts of <he written tFxt and would C<li1St><.jUt'ntly argue for tlw advantages of one inti:"Ipretation o\cr another one, s;;;.y, stre~~..~ng

tlw Sl)inifit dlllC <Jf Hamlet as a Rom;;ntic nt'fU.

antnhcr ernph<:tj~7_i:lg the Tnilitati~rn of !he :;equcncl? u!

C\ent' rlcta!kd '"th<n the play another r:nesc11ting the l'vtl a,; a •.kbate hctv.n·n tlw ideals of action and

47

contemplation. Each would then be evaluated by referring back to the written text of Hamlet, and even the evaluation of the performance would return ultimately into the domain of literature.

Of course, the final assessment of the performance would be based on the finished product, on what is ultimately seen by the public, whereas, through all the stages of rehearsal and setting up, all kinds of possible solutions may be explored. The transition from written text to performance does not happen in a single uninterrupted process, and the various stages between the initial decision to stage a playtext and the opening night involve patterns of selection and rejection of alternatives in order to arrive at what seems to be a unified whole. And in that process of shaping. the words of the original written text (assuming that there is one at all) are only one language among many.

It could be argued that the moment the written word is read aloud, it is translated into another language. Pitch, intonation, inflection, loudness, all such paralz'nguzstic systems, substantially alter the written text. Roman Jacobson quotes the famous example of the actor from the Moscow Art Theatre who was asked by Stanislavski to produce some forty variations on the single phrase Segodnja veceron (this evening) by modifying the expressive tone. 2

Equally, gesture can be read as a language in its own right, and Anaud in fact saw the gestural or kz'nesic as the fundamental code of theatre, a view that has been widely shared. Closely related to the gestural is also the proxemzc code, the system of interaction between groups of figures, and the actor's use of space. Both kinesics and proxemics can be related to the written text but are in no way subordinate to it, and one of the early Czech semioticians, Jirl Veltrusky. considered the linguistic system to both combine and conflict with the physical systems that comprise acting. 3

Looking for a New Methodology None of the issues raised in these preliminary remarks is in any way new or surprising, and all derive from the central questions facing anyone who is involved in any way with theatre: how can theatre be defined and how can it be discussed? What theatre semiotics has to offer in any attempt to tackle those questions is a new methodology. that has its roots neither in literary criticism nor in social history, and starts from the assumption that theatre is made up of a set of codes (linguistic, spatial. gestural. scenographic. illurninational, etc.) coexisting 1n a dialectical relationship with non·theatre. 1

The earliest work in establishing discussion of theatre in semiotic terms can be traced to central Europe. In the 1930s and 1940s there were various attempts by C1.ech writers and theatre practitioners to anaiYl.e the components of theatre. Otakar Zich, Jan Mukarovsky, Jzri Veltrusky, Jz'ndrzch flonzi, and Petr Bogatyrev raised the discussion of the theory and practice of theatre and established the basis for ib

48

analysis in terms of structures and systems of signs. But their work remained obscure - indeed, much of it has yet to be translated into western languages, an indication perhaps of the complexity of their undenaking.

However, in 1970 the first edition of Lillerature et spectacle, the work of a Polish semiotician, Tadeusz Kow1.an, was published,' and although this study does not appear to derive from the earlier Czech work, there are strong common links. Kow1.an 's book is a useful point from which to begin an investigation of the current state of theatre semiotics, since it attempts to codify theatre in very straightforward. clear terms.

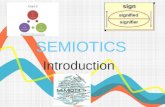

Kowzan distinguishes eight organi1.ational groupings hased on just three central criteria: ~

l'affabulatz'on (story-line), l'homme (man). and Ia 1 parole (words):

l) Performances present (dramatic service).

2) Performances without words processions).

in which all three elements are theatre, opera. recitation. religious

with both story·line and man, but (ballet, mime, silent unema,

3J Performances with story·line and words, but without actors (animations. projections of non·human figures, 'son et lumiere').

4) Performances with story·line only (shadow theatre, silent animation of projection without anthropomorphic figures, non·anthropomorphic robots).

S) Performances with man and words, without story· line (certain rituals. recitation of texts without story line).

6) Performances with man. without the other two elements (gymnastics. certain kinds of performance involving specific skills, some dance, some concerts).

7) Performances with words, without story-line or mao (certain abstract projections using words but without a story).

8) Performances where there is no story·line, words, or actors (most mobile projections. kinesic construction, water· play, firework display. etc.).

In addition to this first attempt to categori1.e and define theatre. Kow1.an also lays down a model for determining the constituent parts of theatre. His system consists in establishing which signs pertain to the actor and which are outside the actor, which are auditory and which are visual, which t>xtst in space and which exist in time and space, etc. The result is shown diagrammatically on the page opposite. ,

Kow1.an then establishes thirteen sign systems as f basic components of theatre. In a later attempt to apply this codification to practical work. he organi1.ed group . projects at dw University of Lyons ll. in which students analyzed performances by each focusing 00

two or thrt>e separate sign systems. The results of thiS

experiment as applied to four plays. Woyzec~; Tartuffe. Planchon's Le Cochon NoiT, and Borchert Draussen vor da Tiir were published in 1976

6

ms of signs. But . much of it hi.! languages, an ~xity of their

' Litt irat ure et ician, Tadeusl this study d0es

T J

I

..

1word z rone

3Mifl'lll

4 GeSture 5 Movement

6 p,1ake-uP

7 ~fair-style 8 eostume

Spoken text

Expression of the body Actor

Actor's external

appearance

Czech work

1 m's book is ~ 9 Accessory Appearance

10 [)eeor of the

11 Lighting stage Outside the •vestigation of I' 1te it attempts . clear terrns. ~anizational .raJ criteria: t 1an), and Ia I

-: . 12 MuSIC 13 sound effects

Inarticulate actor

sounds

'lements are on, religious

d man, but It cinema,

words, but non-human

JW theatre, without

>Omorphic

wut story'lOut story

Jther two formance ·mcerts).

e or man vithout a

•ords, or ruction,

:ze and del for e. His tain to

ch are space result

ns as apply roup thich g on -this

eck, ert's

(

I I I

I I

fhe Nature of the Sign In Litterature et Jpectacle Kowzan declares that, 'Among all the arts and perhaps among all the areas of human activity, the art of theatre is the one wherein the sign appears with the greatest richness, variety, and density'. But he also distinguishes two kinds of sign - the natural, which includes phenomena unprovoked by man (e.g., thunder and lightning as the sign of a storm, skin colour as the sign ofrace, etc.) and the artificial, which is created by living creatures in order to signify or communicate something. And theatre, he declares, is made up entirely of artificial

signs. This concept takes us back to Otakar Zich, who saw

all signs in theatre as serving two ends: to characterize, and to advance dramatic action. 7 Andjindrich Honzl, in his article 'Dynamics of the Sign in the Theatre', sums up Zich's view neatly when he says:

Everything that makeJ up reality on the stage - the playwright 'J text, the actor'J acting, the Jtage lighting -all theJe things in every CaJe stand for other thingJ. In other wordJ, dramatic performance IS a Jet of 1~ns. 8

I The stress laid by the Czech semioticians on analyzing

1 the nature of the Jign in theatre is very clearly expressed in an article by Petr Bogatyrev, 'Les signes du theatre'. 9 Bogatyrev discusses the jlex1bllity of the theatrical sign. the way in which the sign can shift both in its own right and in the way in which it is

, perceived. He gives the now famous examples of the multiplicity of meaning of costume and props - an ermine cape is a sign of royalty in the theatre, regardless of whether the cape is actually made of rabbit fur, just as red liquid poured from a decanter is a sign of wine even though it may be red cordial. On the other hand, in the case of a starving man on stage eating a loaf of bread, that loaf may have no separate sign value in its own right and exist merely as a functional object to be utilized by another actor. for the sign here is not the loaf but the act of eating it.

In addition, an article may have a multiple sign function, and Bogatyrev argues that a costume might simultaneously stand as a sign both of a character's nationality, for example, and of his economic situation. Signs in the theatre. then, assume a set of

Auditive Auditive signs signs (actorl

Space and time Visual signs

Visual (actor I signs Space

Space Visual signs and (outside the time actor I

Auditive Auditive signs signs (outside the actorl

values and functions in their own right, and are infinitely changeable and complex. Moreover, as Honzl points out, since theatrical conventions also change and the theatre of a given time and place will highlight certain components and rank them above others in hierarchical scale, the changeability of this scale will correspond to the changeability of the theatrical sign.

The audience's ability to read signs adds an extra dimension of complexity. Honzl notes how there are times when one or more of the components 'submerges below the surface of the spectator's conscious attention'. This would be the case when what is seen nullifies acoustical perceptions, or when the audience's focus on dialogue pushes visual components into the background.

The early Czech work stresses the need for discussion of theatre in terms of the relationship of component signs to the whole, and it would not be an injustice to that group to cite Honzl once again when he suggests the way in which the discussion should go:

It 1s my belief that with our analysz:S of the changeability of the theatrical sign we have undertaken a taJk that can teJt the trUJtworthineJJ of many definitiom of theatrical art and decide whether those definitionJ make provision for the old and new typeJ of theatre that have orig1'nated in different poetic or dramatic personalitieJ, aJ the reJult of many technical inventionJ, and Jo on. I am also of the opinion that we Jhould reJtore reJpect for the old theory of theatrical art which sees its esJence in acting, in action. 10

What Are the Basic Units? The line of approach to theatre begun by the Czech theoreticians emphasizes the need for a special language with which to discuss the flexibility of theatre art, and, ideally. for a language that can be utilized both by those who create the performance and those who see it. Those involved with the process of creating the performance will inevitably perceive it through a different time continuum, since for them each rehearsal and each performance is a variation not of a constant but of an ideal, whilst for a spectator-critic the time sequence is different, since the performance exists for them in a single circumscribed moment.

49

Indeed, one of the complaints so often made about the impossibility either of performance analysis or of an all-encompassing critical methodology is precisely this question of multiplicity, since the performance at any given time will never be identical to any other But such a complaint can only be upheld if analysis of theatre is treated exclusively as analysis of the final product offered at a given moment. instead of considering all the stages of the theatrical process as coexistent in a symbiotic relationship with each other.

Steen Jansen, the Danish semiotician, notes that it is through the process of rehearsal that the breakdown of a play into szgnifying units is determined. 11 In rehearsals, solutions are tried, rejected. modified, shifted. and realigned in a series of tests that will show whether or not a given situation rematns comprehensible. The variations that take place throughout the rehearsing of a play are not deviations from any single posited ideal, they are merely elements of the total process, and one of the most important aspects of that process is the establishing of those distinct units that makr up the play as a whole.

Jansen defines the fundamental characteristic of the playtext as dramatic structure in the following way: 'It is a coherent succession of distinct units. called dramatic situations; a dramatic situation is a compound of a successive-simultaneous nature of dramatic elements'_tz \-Vhat he is trying to pin down here is one of the central problems not only for theoreticians but also for practitioners: how to establish what the basic units are. over and above the formal division of a piece into acts, scenes. etc. Attempts to establish basic units from a written text alone, or from a single reading of a performance, are bound to be overly restrictive. Yet, as every actor and director knows, units are established during the rehearsal process -- units that may not correspond to a litnary breakdown of the text in terms of plot ;tructures at all. The problem of defining basic dramatic units raises several key questions:

1) Is it p'ossible to determine such ur11ts on a universally applicable basis) (In formulating this question, it should be borne in mind that a potential danger of the semiotic approach is to try and base analysis of theatre on strictly linguistic models. For although linguistics offers a more scientifically structured way of approaching both literary study and theatre, the pluridirnensionality of theatre leads away from, not towards a systematization following linguistic models.)

~) If the units cannot be established from the writtrn text alone, does this imply the presence of a textwithin-a text. rather on the lines of Mallarme's concept of a text of silence and space between the lines of a poem? Can a case be made for the existence of an Inner text, that is read intuitively by actors and directors as thev begin to build the performance i

3) If such an inner tt"xt exists, is it a constant? If. for example. we have five translations of the same playtext, will there also be five distinct inner texts? In

the case of the plavtext from a totally different cultural context, will there be any relation between the inner text perceived in the receiving culture and that pnceived in th<" original context?

A group of Italian semioricians (there is a f1ounshing school of theatrr semiotics in Italy. involving practitioners and critics) has attempted to tackle the problem by trying to identify the special characteristics of language for the stagr. Using the classification of the American philosopher and semiotician C S. Peirce ( 18391914), 13 who devised a complex system of types of sign. the Rizzoli giOup posited that the Indexical level prevails in the dramatic text. According to Peirce. the zndex describrs the concrete, actual relation between sign and object. j usually of a sequential kind (e.g .. smoke as an zndex of I fire, a pointing finger as an Index of a relationship • between the pointn and what is being pointed at).

Since theatre always takes place in situation, the basic level is always the indication of a series of factors - the time and place of the discourse, the speaker(s) involved, etc. The Rizzoli group sought to identify ' delctlc orientations (from dez'xis. referring to the form of language that points to something) as basic units, whereby each change of deictic direction could mark a new unit. So units could be marked by a change in deictic direction, such as a shift from 'this' to 'you'; and these units would not necessarily correspond to changes of speaker. With this kind of work the Italian group have continued the lin<' of approach that sees the task of semiotic criticism as jz'ndmg content units ( of a work rather than defining their matrices.

Is Text an 'Invariable' Element? Whilst this is an interesting line, it does still focus on analysis of the written text in its relation to a possible staging. Alessandro Serpieri, 14 one of the leading Italian theatre semioticians, sees the written text as bearing within it an insuibed range of theatrical signs (an approach close to that of J L. Sty an 1"). whilst another member of the Rizzoli group, Paola Guill Pugliatti, 16

perceives the written text as a network of latent theatrical signs that are only realized in perfonnance.

Others see the relation between the written text and the performance text in different terms: Pagnini defines it as the deep structure of the pnfonnance, using terminology from C:homskian linguistics, 11

whilst Knwzan, perhaps more controversially than any of the other theorists, sees the written text as the lm'llrwble of the final staging All these suggestiof\5 have their source in the common problem of the defining uf dramatic units and the positing of such a

concept in terms of an overall view of theatre, not a cf···: -._ view rt'stricted either to a purely literary or practical _ line.

Patrice Pavis, a leading conternporat y st'miotician, commenting that theatre semiotics has arisen in reaction against 'textual imperialism·. de< lares that the text 'has been restored to its place of one syste!11" among the systrms of the whole of the performance'.·

The issue for hi should be oppo 'whether a text (without) the pe enunciated'_ He t a 'deep struct u performance, an<

What sem1ology interaction betu.·e they can impose made of a text, m z't. t8

What Pavis shows of deep structure; the written text ir the performance. must consider the written text, rehe; enorrnous variety.

A more fruitful the theoretical cor translation theory of a text is th~t comparison of all the invariant in t example, would I written text, in all text (including b performances sue\ media productior updating) and m <

Only such a anywhere near to t and the concept h; in dispelling notior distinctions betwet' it cannot be claim< the form are invari claimed that the w

invariant either_

The Problem c Broadly speaking, far has been conu and delmeating the it down into comp< tenns of attempting text, as the Italians differing approach< to be perceived as inadequacy of exis not only whether 'language' in its o" ~oint that the law g 11 rs 'articulated lik arrive at a common

With the questio area of semiotic stu describing the lingo theatre text is base

'X

trices.

t?

issue fm him is not whether 'textual semiotics be opposed to performance semiotics' but

a text can be analyzed semiotically before the performance during which the text is

enunciated'. He rejects the notion of the text as either ··deep structure' or an 'invariable' of a given

and suggests that:

semiology has to explain, therefore, is the .o ...... ,,r,nn between the two systems, the 'construction'

can impose on each other; that which can be of a text, and what the stage situation can say to

· What Pavis shows very clearly is that the notions both of deep structure and of the invariable are still keeping the written text in a position of special status vis-a-vis t}le performance. And any search for an invariable IJIUSt consider the question of the relationship between written text, rehearsals, and performances in all their enormous variety.

A more fruitful line of approach might be to apply the theoretical concept of in variance as posited in the rranslation theory of A. Popovic ~ that the invariant of a text is that which can be discerned from a comparison of all the versions of the original. Hence the invariant in theatre terms of The Tempest, for example, would be that which is constant in the written text, in all performances based on that written text (including ballet, puppet plays, experimental performances such as Pip Simmons's short multi· media production, or Michael Fleck's Hawaiian updating) and in all rehearsals.

Only such a comparative method can come anywhere near to tackling the problem of in variance, and the concept has been useful in translation theory in dispelling notions of invariance based on formalist distinctions between form and content. Indeed, just as it cannot be claimed that either the subject matter or the form are invariants in translation, so it cannot be claimed that the written text or the performance are invariant either.

The Problem of Theatre 'Language' Broadly speaking. then, work in theatre semiotics so far has been concerned with problems of codifying and delineating theatre, whether in terms of breaking it down into component parts, as Kowzan does, or in terms of attempting to establish basic units of a written text, as the Italians have been doing. What binds these differing approaches together is a concern fqr theatre to be perceived as a totality and an awareness of the inadequacy of existing terminology. The problem is not only whether theatre can be considered as a 'language' in its own right (following Julia Kristeva's point that the law governing any social practice is that it is 'articulated like a language' 19). but also how to arrive at a common language for discussing it.

With the question of language at the centre, one area of semiotic study has focused on the problem of describing the linguistic text as a starting point. The theatre text is based on dialogue, on the dialectical

relationship between /-you in the present, whereas the prose text is. based on a removed he. Even where there is narrative dialogue, this can be considered as distinct from dramatic dialogue, as Veltrusky shows when he says, 'Narrative dialogue differs from the dramatic chiefly in that it emphasizes the succession of speeches rather than the simultaneous unfolding and interplay of the contents from which they spring'. 20

Having made this distinction, Veltrusky goes on to raise a question that has since been the focus of attention of several semioticians: the problem of the author's notes and comments within the body of the written text, known in English (and Veltrusky feels that this description is misleading) as the stage directions. Veltrusky points out that these notes are eliminated in performance, 'and the resulting gaps in the unity of the text are filled in by other than linguistic signs'. He feels that this process is not arbitrary, but is 'essentially a matter of transposing linguistic meanings into other semiotic systems'. However, he also shows that the extent of the transposition depends on the weight those notes carry within the text ~ i.e., on the importance of the gaps created by their deletion.

Analyzing the stage directions of Pirandello's Tonight We Improvise, Steenjansen21 shows that they constitute the presence in the text of the dramatist as a structural element. The same might be said for some of Arnold Wesker's works. Thus, if we consider the following stage direction, it is unclear as to what it actually is:

Dobson returns at this point and sits down, waiting for the next move. Remember, he has already caught them embracing. Dave and Ada glance at each other, Dave shrugs his shoulders. Ada proceeds to lay out a clean shirt for Dave, he is drying himself The rest of this scene happens while Ada prepares a salad. They never get round to eating it. 22

How far can this be taken as minutely detailed instructions to the actors (which raise, as Veltrusky has also shown, important issues of the author's attempts to exercise control over the performers), and how far is it essentially literary, denoting the presence of the author inside the playtext, making himself accessible not to the audience but to the reader? For, as semioticians have pointed out, the existence of a written text implies a reader. and it may indeed be that certain playwrights have constructed texts that question assumptions about reading those texts, in much the same way as novelists this century have questioned assumptions about reading prose.

Leaving aside for a moment the question of the playtext in its dialectical relationship with performance, and remaining with the question of reading written words, it is possible to distinguish several broad types of reading:

1) The purely literary reading (e.g., a play read as part of an academic drama or literature course, or a volume of 'complete plays' read consecutively).

51

2) The directorial reading (which may involve a process of decision-taking. to assess whether or not to stage the play).

3) The actor's reading (which will focus on the performability of certain roles).

4) Rehea~al reading (which will involve the inclusion of paralinguistic signs - pitch, tone, inflexion, etc. -and may also involve gesture).

5) The post-performance reading (a text read for the first time after seeing a performance, when the reading will contain within it the memory of the staging as a component).

In all these different types of reading, the relationship between the stage directions and the dramatic dialogue will inevitably vary. There is, therefore, a notion of multiplidty in the act of reading a playtext that corresponds to the notion of multiplicity in performances of that text. From what appeared to be an essentially literary semiotic approach. we have come round full circle back to the inadequacy of perceiving the written text as either the primary or the invariant component of theatre.

Anne Ubersfeld points out that the written text is incomplete (troue). 23 She cites as an example the opening moments of Moliere's The Misanthropist and points out that the reader knows nothing about the contextual situation from the text alone: 'Are the two characte~ already there, on stage. or do they arrive? How do they arrive? Do they run on, or not? Which one follows the other, and how?' Ubersfeld feels that the answers to these questions, which must be determined by the time the performance takes place, derive from close textual work. However. she makes a distinction between T, the written text, P. the performance text, and T 1• a text that is interposed between the two but is a necessary component of the final product. Set out as an equation, she proposes: T + T 1 = P, where T 1 is the text that provides the answers to the questions posed by the gaps left in T. Approaching the issues from a completely different angle. she too posits the question of the boundaries of the written text and the possible existence of an inner text to be read between the lines.

The Performer and the Audience In addition to the work outlined so far. from which it can be seen that theatre semiotics is proceeding along many fronts, there is also the vast question of the relationship between performers and audiences. There is a whole science of audience-reader response. rezeptszoniisthetik. that utilizes work in sociology and semiotics, and with theatre the issue is made more complex by the consideration of the audience as a component of the theatre and not only as a receiver.

Bogatyrev, for example, pointed out the complexity of the audience response to a folk play or medieval pageant, where simultaneous layers of perception were involved, as the audience acceptt'd I) the play as thing, 2) the functlon of the play as ritual. 3) their familiarity with friends and neighbours as actors, and

so on. Moreover. just as the signs of theatre change according to different epochs and conventions, so the expectations and role of the audience also change. In addition, although every spectator is individually a receiver, the way he is actually affected will vary according to the collective response of the audience as a whole (e.g .. different reactions of the individual spectator in a full house as against an almost-empty one).

Veltrusky. together with the Czech group in I general, was much concerned with the question of the relationship between performers and the audience, and suggests that within this unit there are two distinct relationships: the actor-spectator relationship between the actors. and the actor-spectator relationship within the audience:

Just as there is an actor-spectator relationship between the actors, so there is another actor-spectator relatz'onshzp within the audience. Both are grafted on the basic relatz'onshzp between the actual actor and the actual spectator, which they complement and help to buz'ld up but with which they can also clash, even to the extent of disrupting the performance. An interesting example of such disruptzon is mentioned by Antoine. Dunng the performance of a comedy, a wellknown critic, rather hostz'le to the Theatre Libre, was at one poz'nt so overcome by laughter that the whole audz'ence looked at him and laughed with him and they laughed so long, says Antoine, 'that we could no longer regain our self-possession on stage'. By overreacting to the conative function of acting, this spectator unwittingly 'stole the show' from the actors. 24

On the other hand, Jan Mukarovsky, one of the leading Czech theoreticians of the 1930s and early 1940s (though not primarily a theatre semiotician), considers the audience to be 'omnipresent in the structure of a stage production·, 25 and at the same time questions the whole notion of the 'audience' in general as being too abstract a concept.

Theatre semiotics, then, is vast in its own right as a discipline seeking to treat theatre as theatre 'scientifically', and it draws on many other related fields: history. sociology. linguistics. philosophy. aesthetics. architecture. physics, mathematics. translation studies - the list continues indefinitely. With such a wide range, it follows that certain approaches will favour the utilization of certain methods of terminology in preference to others, and it is this that has presented a stumbling block to the advancement of work in theatre semiotics in Britain in the past.

The use of what seems to some to br a highly specialized language can be off-putting. and there have been occasions when valuable ideas have been encased m a language that has been seen as obscurantist and over-academic. But although thi5 kind of work cannot be excused, it should be noted that many of tht> complex neologisms stem from an att<"mpt to create a new kind of language in which tD

talk in ad scho com liter:

In en co lang wide speei tWO

impr thea I hand the f of th equa that

defea both work

will 1 pro~

Not~

Fo Hawko New r

2 Ro Pcxtic Mass.:

3 Jiri Theat1 rd.s .• (Camt

4 Th ~twe~: and B New J_

5 Ta Paris: from t

6 Tao theatr< ·~hqJ

7 Th Eng lis! (Aesth. quotro discuSS> rntitle. 1931-1

8 jim reprint

9 Pn (1971),

10 jit

II Sto Biblioi

12 54

13 ~cit. n 'Peirctl Sight,f,,

~tor

.re grafted actor and t and help ··lash, even

about theatre, since the existing one has proven ,,,.nn:n... The gap between practitioners ·and

is further widened by the absence of a ¢p-~mon language and by the scholars' tendency to use literary terminology in the discussion of theatre. •. In future issues of Th~atre Quarterly it is hoped to encourage discussion in semiotic terms, but in a language that will be accessible and utilizable to a wide spectrum. Where necessary, glossaries of specialized terms will be provided, and ids hoped that two positive shifts will be made in the direction of iJPproving communication between people engaged in t}teatre: firstly, that those who reject semiotics out of hand will come to consider its ·potential usefulness in

;_ the furtherance of a universally acceptable discussion of theatre; and secondly, that those semioticians who equate accessibility with dilution will come to realize that isolationism is both elitist and ultimately selfdefeating. The early work in Czechoslovakia involved both scholars and theatre practitioners, and valuable work in France and Italy is following similar lines. It will perhaps not be too long before we begin such projects here.

Notes and References

I For a readable introduction to semiotics, see Terence Hawkes, Structuralism and Semiotics (London: Methuen, New Accents, 1977).

2 Roman Jacobson, 'Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics', in T. Sebeok, ed., Style in Language (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. 1960), pp. 350-77.

~ Jiri Veltrusky. 'Dramatic Text as a Component of Theatre' (1941), reprinted in L. Matejka and I. Titunik, eds., Semiotics of Art: Prague School Contributions (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1976), pp. 94-118.

4 The term 'non-theatre' follows Yuri Lotman's distinction between culture and non-culture, as outlined in Y. Lotman and B. Uspensky, 'On the Semiotic Mechanism of Culture', New Literary History, IX, 2 (1978).

5 Tadeusz Kowzan, Litterature et spectacle (The Hague; Paris: Mouton, 1975). Quotations from Kowzan are taken from this text.

6 Tadeusz Kowzan, Analyse semiologique du spectacle thetitrale (Universite Lyon 11: Centre d'etudes et de recherches theatrales, 1976).

7 The work of Otakar Zich has not been translated into English. His study of theatre, Estetika dramatickeho umeni (Aesthetics of Dramatic Art, Prague, 1931) is extensively quoted by other members of the Prague group and is discussed at some length by Irena Slawinska in an article entitled 'La semiologia del teatro in statu nascendz': Praga 1931-1941', Biblioteca teatrale, 28 (1978), pp. ll5-35.

8 Jindrich Honzl, 'Dynamics of Sign in the Theatre' (1940), reprinted in Matejka and Titunik, op. cit., pp. 74-94.

9 Petr Bogatyrev, 'Les signes du theatre', Poetique, V111 (1971), pp. 517-30.

10 Jindrich Honzl, op. cit., pp. 90-l.

11 Steen Jansen, 'Problemi dell'analisi dei testi dramatici', Biblioteca teatrale, 28 (1978), pp. 14-44.

12 Steen Jan5en, op. cit., p. 29.

13 C. S. Peirce's work is discussed by Terence Hawkes, op. cit. There is also a helpful chapter by Max Fisch, entitled 'Peirce's General Theory of Signs', in Thomas Sebeok, ed., Sight, Sound, and Sense (Bloomington: Indiana University

Press, 1978), pp. 31-7:t

14 Alessandro Serpieri, 'lpotesi teorica di segmentazione del testo teatrale', Strumentz- crz'tzcz·, 32/33 (1977), pp. 90-135.

15 J. L. Styan, The Elements of Drama (Cambridge University Press, 1969).

16 Paola Guill Pugliatti, I segni latenti. Scrittura come virtualita scenica in King Lear (Mesina-Firenze: D'Anna, 1976).

17 M. Pagnini, 'Per una 5emiologia del teatro classico', Critici, IV, 2 (1970).

18 Patrice Pavis, in a reply to five questions on theatre semiotics circulated to eight people, published in 1/S, September-December 1978. Pavis' full-length study in French on theatre semiotics is Probliimes de semiologie t hetitrale (Presses de I'Universite de Quebec, 197 6). More recently Pavis has been engaged in producing a glossary of theatre terminology.

19 Julia Kristeva, 'The System and the Speaking Object', Tz'mes Literary Supplement, 12 October 1973.

20 JiTi Veltrusky, op. cit., p. 96.

21 Steen Jansen, 'Struttura narrativa e struttura drammatica', in Questa sera si recita a soggetto. Rivista italiana di drammaturgia, 6 (Roma, 1977).

22 Arnold Wesker, I'm Talking About jerusalem, Act II.

23 Anne Ubersfeld, Lire le theatre (Paris: Editions sociales, 1978), p. 24.

24 Jiri Veltrusky, 'Contribution to the Semiotics of Acting', in L. Matejka, ed., Sign, Sound, and Meanzng (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1976), p. 589.

25 Jan Mukarovsky, 'On the Current State of the Theory of Theatre', reproduced in a collection of his essays, entitled Structure, Sign, and Function (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1978), pp. 201-20.

Theatre Studies The 'Theatre Studies' series enables regulo.r subscribers to obtain Jour of TQ's most important publications at a saving of almost cnre-third over regu/o.r retail prices. Titles fur the first subscription series are:

Beckett: a Theatre Bibliography compiled by Virginia Cooke Other Spaces: New Theatre and the RSC by Colin Chambers Letters from a Theatrical Scene-Painter by T. W. Erle (1880) World Guide to Performing Arts Periodicals an ITI directory compiled by Christopher Edwards

By subscription, all Jour titles cost only £25.00 ($60.00) post free, compared with the retail pn·ce, befure postage, of £36.90. Order from the Subscriptions Department address on page 2 of this issue.

53