Surreal Eden

-

Upload

princeton-architectural-press -

Category

Documents

-

view

244 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Surreal Eden

Surreal EdenEdward James and Las Pozas

MARGARET HooKS

with photographs by

Sally Mann

Michael Schuyt

Lourdes Almeida

Marilyn Westlake

Luis Félix

and Avery Danziger

Princeton Architectural Press, New York

P.2 P.3

for kim

reece

and freddie

P.4 P.5

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

Preface

Chapter 1 A Child’s Walled City

Chapter 2 Poet and Patron

Chapter 3 Among the Surrealists

Chapter 4 The Magic of Mexico

Chapter 5 Snow Falls on orchids

Chapter 6 Builder of Dreams

Chapter 7 The House with Wings

Chapter 8 El Inglés in Xilitla

Chapter 9 Light in the Forest

Chapter 10 Triumph of Time

Afterword

Bibliography

Photography credits

About the photographers

Index

6

8

12

20

28

49

61

87

113

137

146

161

169

174

177

178

180

P.4 P.5

P.10 P.11

S u r r e a l

E d e n

P.10 P.11

12 Surreal Eden

Chapter 1

A Child’s Walled City

The flames burned bright in the cold October night, as the crowd of torchbearers some two hundred strong turned into the broad carriageway leading to the vast mass of West Dean, its battlements

and flint facade softened by the blaze of light. The upturned faces of the assembled tenants, workers, and servants glowed in the shadows, and a cheer welled up at the approach of the carriage that was bringing William James and his wife, Evelyn, back to the estate with their long-awaited son, Edward Frank Willis James. After the horse-drawn carriage had deposited them at the front entrance, the proud parents disappeared into the house, then reappeared at an upper window holding up baby Edward for everyone to see. The crowd roared its approval, there were banners inscribed “Welcome Home” and “Long Life and Happiness,” and the sky lit up with streaks of light as the throng was treated to a fireworks display to honor the new heir.

Edward James’s birth in August of 1907 at Greywalls, the family’s summer home in Scotland, was cause for great celebration. After eighteen years of marriage, and four daughters, the boy’s birth provided a male successor to the vast West Dean estate and immense wealth of the James family. The gala events, announced prior to the baby’s homecoming in an eight-page program of festivities, continued with the christening where a representative of King Edward VII, for whom Edward James was named, delivered a gold goblet from his Majesty to his new godson. The presence of royalty was not uncommon at West Dean, owing to the couple’s standing in the stylish Marlborough set. Just three days after the

13A Child’s Walled City

baptism, Spain’s King Alfonso and his entourage were guests for several days of shooting on the expansive grounds of the twelve-thousand-acre estate in the bucolic West Sussex countryside.

Purchased by William James in 1891 two years after his marriage to Elizabeth Evelyn Forbes, West Dean was once scathingly described by a critic as “limp Gothic.” The couple had it remodeled and redecorated to match their sumptuous Edwardian lifestyle. When they moved in, it had the latest in modern comforts: there was electric light in every room, a hydraulic food lift, and a state-of-the-art steam laundry. William Dodge James (Willie) was the British-born son of a second marriage by American steel and railroad magnate Daniel James to Elizabeth Phelps, daughter of an heir to the Phelps Dodge mining and timber fortune. Willie and his two brothers, Arthur and Frank, were destined to inherit their parents’ enormous fortune and quickly became popular in English high society not only for their great wealth, but also for their daring exploits as avid sportsmen and globe-trotting adventurers.

Frank and Willie were the most renowned for their exploits. They had a very large yacht called the Lancashire Witch in which they traveled the world. When they tired of that they went on expeditions to Africa, led by Frank. He and Willie were the first Europeans to penetrate the deserts of Somaliland and Eritrea by caravan, and they apparently reached the source of the Nile just a few years after its discovery. In 1890, Frank, the only remaining bachelor of the trio, went on a hunting expedition to Sierra Leone, where he was trampled by a wounded elephant and died. The brothers had brought back endless trophies from their trips that decorated the halls of West Dean; Edward described them as “hartebeest and impala and things with wonderful curly horns.” There was a rhinoceros’s head and the skull of a hippopotamus and even a stuffed polar bear from Greenland, almost eight feet tall. Edward later gave the bear as a gift to Salvador Dalí, who cut drawers in its stomach and had it dyed purple!

Edward’s mother, known as Evie to close friends and family, was a member of the aristocratic Forbes family. Their ancestral home, Castle Newe, bordered the summer home of the British Royal Family at Balmoral,

1414

and her father, Sir Charles Forbes, became a close friend of Edward VII, then Prince of Wales. The Forbes family was no longer wealthy, but they had a respectable noble lineage dating from the thirteenth century. Evelyn Forbes’s marriage into the James family fortune provided her precisely with the resources she had lacked to become the quintessential Edwardian hostess to which she had aspired from youth.

The rumor and innuendo that has persisted for decades as to whether Willie James was actually Edward James’s biological father is fueled by accounts of the King’s many visits to West Dean. One of these visits took place nine months before Edward’s birth and is interpreted by some as evidence for his actually being Edward’s real father. By Edward’s telling, however, it was the proximity of Balmoral Castle to Castle Newe that brought together the two families a generation earlier and marked the entry of royal lineage into his family: “Rumor had it that I was the bastard son of Edward VII, which I was not. I was, in fact, his grandson,” he clarified, in Patrick Boyle’s documentary, The Secret Life of Edward James, shown on British television in 1978. He believed his mother was conceived as a result of a romance between his grandmother, the lovely Lady Helen of Newe, and the handsome young Prince of Wales.

The death of Edward VII in 1910 put a cramp in the style and social cache of the Marlborough set. Evelyn James was then in her mid-forties, and her health was not good. In 1911 she underwent surgery for a heart condition, and the family rented a villa at San Remo for the winter to aid her recovery. It was Edward’s first experience of travel abroad. He described how the family traveled to one of his biographers, Philip Purser, in Where Is He Now? The Extraordinary Worlds of Edward James. It is an indication of his childhood world, where there was a servant for every task and money was irrelevant:

We travelled with an enormous number of servants, including

valets and footmen. We took practically half a Channel steamer

and almost a whole train. My sisters took their dogs . . . and their

canaries and each of them had a governess and . . . a maid and I

Surreal Eden

15A Child’s Walled City

had a nurse and a nursemaid, and my mother had two maids and

my father had a valet and a chauffeur. We didn’t take a car with us;

we bought one there, because you couldn’t hire a car in those days.

Early the following year, Willie James became very ill while on a steamer bound for South Africa. He returned to London, where he was diagnosed with bladder cancer and hospitalized. Edward was sent to stay with an elderly relative, and in March 1912, six months before his fifth birthday, he was told his father had died. Although he was very young, he was deeply affected by his father’s death and wept inconsolably for hours. Adding to his trauma, very shortly afterward his mother fired his beloved Irish nanny, the person he was closest to as a child. For years Edward remained particularly bitter toward his mother for this, which he interpreted as a deliberate attempt to hurt him.

At best, Evie was aloof with her children, and despite a veneer of filial piety, each of them resented her in their own unique way. Edward repeatedly said he disliked her immensely and over the years told many tales of her callousness. One of his favorites was the occasion when she was dressed in elegant splendor for Sunday morning church and called upstairs for a nanny to send down one of the children to accompany her to the service. “Which one, Madam?” the nanny asked. “Whichever goes best with my blue dress,” she apparently replied.

Despite their wealth, Willie James’s death left the family quite financially strapped. Though he was generous to them in his will, a new British law requiring cash payment of death taxes forced an ill-timed sale of his railroad stock in order to provide his wife and daughters with the annual allowances he had stipulated. Edward did not fare so well—only six hundred pounds a year remained to maintain West Dean, which was to be held in trust until his twenty-fifth birthday. This led to piecemeal sales of large portions of the estate and meant a humiliated Evie had to move into the estate’s Monkton House hunting lodge with her new husband, Colonel Dosie Britton, and rent out the West Dean mansion.

16 Surreal Eden

At age eight, Edward was packed off to the first in a series of English boarding schools that he utterly detested. He complained of the bullying, the canings, and the terrible food. The masters were obsessed with punctuality and enforced a Spartan regimen with deplorable sani-tary conditions. At one school, the short, slight Edward was frequently elbowed out of the way in the morning rush of eighty boys trying to use just eight lavatories, and at another he described how several boys had to bathe in the same bathwater, which was grey and coated with scum if one were unlucky enough to be one of the last boys to bathe.

To escape his fractured family life and the horrors of these schools, he began to fantasize about a dreamlike walled city to which he could magically retreat. Inspired by a painting of a medieval town that hung on his nursery wall, he called this secret fantasy place “Seclusia,” and the dream of it remained with him throughout the years. Decades later, he published a fanciful epic called Reading into the Picture, based upon Seclusia, in which he invites the reader to “enter this fantastic town.” It echoes what would become a recurring theme in his life: the search for a refuge and the discovery of the perfect romantic retreat of his dreams.

Edward entered Eton, England’s most prestigious private school, at the age of thirteen. Photographs of him at the time show an attractive boy who looks younger than his years. He was a daydreamer who loved music and reading, much to his mother’s disdain, and to the detriment of his academic grades. As the pressure to perform academically at Eton intensified, he became increasingly distracted. A log of his misdemeanors he kept at the time points to the ludicrous emphasis on punctuality at the school; he noted that on one occasion he was given fifty lines for being half a minute late for Sunday Chapel! The harder Edward tried to be on time, the more often he was late, until his concern with punctuality developed into strange, obsessive behavior. Further fraying his nerves was the way in which he was bounced around from place to place during the school holidays, perhaps contributing to his later nomadic tendencies. His mother, in order to ensure her income, was constantly changing their abode so she could rent out the family homes. This meant he never knew

17A Child’s Walled City

exactly where he would be going when he went “home” for the holidays; often as not, it was to stay in London hotels or on visits imposed upon relatives or friends.

On one such visit, a very distasteful incident occurred. He and his mother were invited for the weekend to the home of Lord Harcourt, a prominent member of the English aristocracy. What Evelyn James had conceived of as a social coup turned into a nightmare for her son. During their stay, Edward had to repeatedly reject Harcourt’s sexual advances, which he was afraid to reveal to his mother. On the final morning of their stay, apparently in an attempt to cultivate the friendship, his mother insisted he go upstairs and make some polite farewell remarks to Harcourt, who was in bed at the time. He tried to resist, but Evie was adamant. He approached Harcourt’s bedroom with trepidation, entering at one end of the seemingly endless room, and walked toward the bed, raised upon a dais at the opposite end. Harcourt kept telling him to come closer and closer, and when he finally did, mumbling his little prepared speech, Harcourt suddenly pulled back the bedclothes showing his nakedness and exposing a large erection.

Edward rushed from the room very upset and ran to the waiting car where he burst into tears. His mother asked what was wrong and he told her. She was furious and created a society scandal, endlessly re-counting the incident to her affluent friends. Within two years Harcourt had killed himself, and while the episode with Edward was not the first of Harcourt’s molestations nor the sole reason for his disgrace, Edward’s much-gossiped-about association with this suicide was deeply troubling to him for many years. Not long afterward he began showing signs of a nervous crisis, breaking down one day in his mother’s presence and sob-bing uncontrollably. His mother became sufficiently alarmed to take him to a psychiatrist. While he found the treatment inadequate, having some-one to talk to about his fears enabled him to assimilate the episode and, though shaken, move on.

Two events took place at Eton when he was fifteen that point to the passions that later propelled his life. He began writing poetry probably

18 Surreal Eden

around the summer of 1922, as he noted almost a decade later in a jacket note to his second book of poetry, Juventutis Annorum:

Now I see myself at that time so discouraged by misfortunes of the

psyche—those relentless attacks from parents and teachers, against

my immortal soul. This rock of straw took the shape of my early

poetic output. For that versification was my only escape, my only prop

against a tremendous downward pressure of fate, family and fail-

ure . . . my lonely little talent of rhyme, led me from stepping-stone to

stepping-stone of doggerel and dream.

Later the same year, he became the surprising recipient of Eton’s prestigious Geoffrey Gunther Memorial Drawing Prize. It was unexpected both by Edward, who had actually forgotten to put his name on the drawing, and his fellow Etonians, who were a little miffed that such a young, self-effacing student had been chosen from among so many contenders.

The judge was the respected art critic Roger Fry, who upon announcing the winner to the student body explained why Edward’s drawing was the best. Harold Acton, who was in the room at the time, later described the incident in his autobiography, recalling Fry’s hav-ing remarked that in painting, “Most people were interested merely in technical skill, by which little or nothing could be achieved. Ideas and clarity of vision were of primary importance. . . . ” This recognition of his artistic ability was never acknowledged by Edward’s mother. In fact, it further strengthened her determination that he should choose a political career and abandon his interest in the arts. But Fry’s comments, with their emphasis on ideas and vision as a pivotal force in art, were integral to Edward’s development as a major art patron.

In October 1926, Edward went up to Oxford and began what were among the happiest years of his life. He was able to put his mother at a distance and immerse himself in the company of some of his generation’s most prominent aesthetes. Encouraged in his poetry for the first time,

19A Child’s Walled City

he threw himself into the literary intellectual life of Oxford, even becoming editor for a time of the undergraduate magazine Cherwell. His first volume of poetry, simply entitled Poems, was published in 1926 by the Shakespeare Head Press, which also published works by renowned English writers Evelyn Waugh and Sacheverell Sitwell. In 1928, when he turned twenty-one, he inherited his late uncle Frank’s considerable fortune, allowing him to spread good cheer and make new friends. His contemporaries recalled more time spent at his lavish meals than at lectures or tutorials. In his poem “Summoned by Bells,” John Betjeman memorialized the endless discussions on Oscar Wilde and T. S. Eliot over breakfasts of champagne and Virginia ham in Edward’s rooms.

In fact, his rooms on Canterbury Quad, the finest student lodgings at Christ Church, were the largest available, and he had four instead of the customary two. It was in decorating these rooms that he first exhibited his lifelong talent for creating surreal environs through the juxtaposition of disparate materials or objects and the transformation of their functions. His drawing room was hung with lavish Gothic tapestries interspersed with London Underground travel posters, and about the room he had arranged neoclassical busts of Roman emperors, their mouths wired with speakers that blasted forth the latest in French music and American jazz. The ceiling was painted a dark purple with a light purple trim, and in gold lettering on a black background frieze there was inscribed a quote in Latin he attributed to Seneca: “Art is long, Life is short, but you can make life seem longer if you know how to use it.” He believed that he did and was anxious to prove it.

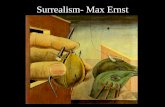

Dense fol iage covers much of Las Pozas

P.97