Stress management and diabetes mellitus, a problem complex based holistic care model

Stress and Diabetes a Review of the Links

Click here to load reader

-

Upload

ermir-kafazi -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Stress and Diabetes a Review of the Links

7/23/2019 Stress and Diabetes a Review of the Links

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/stress-and-diabetes-a-review-of-the-links 1/7

12Diabetes Spectrum Volume 18, Number 2, 2005

Stress and Diabetes: A Review of the LinksCathy Lloyd, PhD; Julie Smith, BSc, RGN, MSc; and Katie Weinger, EdD, RN

Evidence suggests that stressful experi-ences might affect diabetes, in termsof both its onset and its exacerbation.In this article, the authors reviewsome of this evidence and consider

ways in which stress might affect dia-betes, both through physiologicalmechanisms and via behavior. Theyalso discuss the implications of thisfor clinical practice and care.

In recent years, the complexities of therelationship between stress and dia-betes have become well known buthave been less well researched. Somestudies have suggested that stressfulexperiences might affect the onsetand/or the metabolic control of dia-betes, but findings have often beeninconclusive. In this article, we reviewsome of this research before going onto consider how stress might affectdiabetes control and the physiologicalmechanisms through which this mayoccur. Finally, we discuss the implica-tions for clinical practice and care.Before going any further, however,the meaning of the term stress must beclarified because it can be used in dif-ferent ways. Stress may be thought of as a) a physiological response to anexternal stimulus, or b) a psychologi-cal response to external stimuli, or c)stressful events themselves, which canbe negative or positive or both. In thisarticle, we address all three aspects of stress: stressful events or experiences(sometimes referred to as stressors)and the physiological and psychologi-cal/behavioral responses to these.

Role of Stress in the Onset of DiabetesStressful experiences have been impli-cated in the onset of diabetes in indi-viduals already predisposed to devel-oping the disease. As early as thebeginning of the 17th century, theonset of diabetes was linked to “pro-longed sorrow” by an English physi-cian.1

Since then, a number of researchstudies have identified stressors such

as family losses and workplace stressas factors triggering the onset of dia-betes, both type 1 and type 2. For

example, Thernlund et al.2 suggestedthat negative stressful experiences inthe first 2 years of life may increasethe risk of developing type 1 diabetesin children. Other factors, such ashigh family chaos and behavioralproblems, were also implicated. Otherresearch has also supported thehypothesis that stressful experiencescan lead to increased risk for develop-ing type 1 or type 2 diabetes.3–5

In a large population-based surveyof glucose intolerance, Mooy et al.6

demonstrated an association betweenstressful experiences and the diagnosisof type 2 diabetes. Although this wasa cross-sectional study, the authorsinvestigated stress levels in peoplewith previously undetected diabetes inorder to rule out the possibility thatthe disease itself influenced reports of stressful experiences. They also tookother factors into account, such asalcohol consumption, physical activitylevel, and education.

Bjorntop7 has attempted to explainthe physiological links between stress-ful experiences and the onset of dia-betes. He argues that the psychologi-cal reaction to stressors of defeatismor helplessness leads to the activationof the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal(HPA) axis, leading in turn to variousendocrine abnormalities, such as highcortisol and low sex steroid levels,that antagonize the actions of insulin.At the same time, an increase in vis-ceral adiposity (increased girth) isseen, which plays an important role indiabetes by contributing to insulinresistance.8 Increased visceral adiposi-

ty can be measured by waist-to-hipratio. In the Mooy et al. study of type2 diabetes,6 there was only a weak

Address correspondence and requestsfor reprints to Dr. C.E. Lloyd, Faculty

of Health & Social Care, The OpenUniversity, Walton Hall, MiltonKeynes, MK7 6AA, U.K.

Feature Article/Lloyd et al.

Abstract

7/23/2019 Stress and Diabetes a Review of the Links

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/stress-and-diabetes-a-review-of-the-links 2/7

122Diabetes Spectrum Volume 18, Number 2, 2005

association between stressful experi-ences and waist-to-hip ratio, suggest-ing that other factors, so far unidenti-fied, may play a mediating role.

Where stressful experiences havebeen implicated in the onset of type 1diabetes, researchers have often

attempted to explain this in terms of the effects of stress on the autoim-mune system.2 Bottazo et al.9 hypothe-sized that environmental factors (e.g.,viruses or toxic agents) trigger theautoimmune destruction of the -cellsin genetically predisposed individuals.

However, not all studies havedemonstrated a link between stressfulexperiences and the development of diabetes. In a recent review,Cosgrove10 argued that many of thestudies that have demonstrated a link

between stressful events and type 1diabetes have been of small size andlacked appropriate control groups.Cosgrove cited one large Swedishstudy11 indicating that there was noassociation between stressful eventsand the onset of type 1 diabetes.However, this study included a wideage range (15–34 years) of newlydiagnosed people. Often quite vastdifferences in the type and intensity of life changes are found at the differentages within this range, and changes insocial supports (known to be a bufferto stress) are frequent during theseyears, especially in the teenage years.This may have masked any associa-tion between stressful experiences andthe development of diabetes.

Given the numerous measurementstrategies and different study popula-tions that have been investigatedthrough the years, definite conclusionsare difficult to reach. Smaller in-depthstudies have usually demonstrated alink between stress and diabetes,whereas larger studies using self-report checklists to measure theoccurrence of stressful experienceshave sometimes failed to support thislink. Much more conclusive is the evi-dence regarding the relationshipbetween stressful experiences andmetabolic control in those alreadydiagnosed with diabetes, and it is tothis research that we now turn.

Stress and Diabetes ControlIn recent years, some researchers haveturned their attention to the possibili-ties of stressful experiences influencingdiabetes control.12–15 This potential

influence is important, not only forthe often debilitating effects poorblood glucose control can have ondaily life, but also because of theknown association between chronical-ly high blood glucose levels and thedevelopment of diabetes complica-

tions.16

It is a complex area of research,much of it having been conducted inchildren and adolescents, with fewerstudies in adults or in those with type2 diabetes, and using a number of dif-ferent measurement tools. Stressfulexperiences have been recorded usinganything from simple checklists tolonger self-report questionnaires, toin-depth interviewing techniques.Most studies in this area have notdetermined the type or severity of

stress that may influence changes inglycemic control, nor have they beenable to fully address the role of otherfactors in mediating the impact of stress on glycemic control. Moreover,it is difficult to determine the tempo-ral relationship between stress andhealth, not least because poor healthoften leads to adverse experiences.

A number of laboratory studieshave been conducted to demonstratethe effects of specific stressful situa-tions (for example, arithmetic prob-lem solving, unpleasant interviews) onblood glucose levels. Many of thesestudies have demonstrated that thesetypes of stressors can destabilize bloodglucose levels, at least for hours at atime.17 However, a major criticism of this approach is that it does not mir-ror the real world in which individu-als with diabetes live.

Other studies have focused on thatreal world and have attempted tomeasure naturally occurring stress.18–21

These later studies are not withoutproblems however, such as, the myri-ad possibilities for measurementand/or observation, which makescross-study comparisons difficult.Stress may take the form of day-to-day hassles, and it may be that majorlife events (death of a close relative,losing a job) are an added layer of complexity, along with long-termchronic difficulties (e.g., providinglong-term care for a relative or long-term unemployment).

In an attempt to overcome some of the previous methodological limita-tions, a prospective in-depth investiga-tion into the relationship between

stressful experiences and changes inglycemic control over time wasdesigned.21 Individuals with type 1diabetes were interviewed using an in-depth interview schedule and then fol-lowed up quarterly for a year withmeasures of diabetes control (hemo-

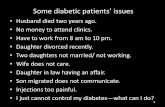

globin A1c [A1C]). Unlike previousstudies, the participants were askedabout both negative and positivestressors in their lives. The resultsshowed that those whose glycemiccontrol deteriorated over time weremore likely to report negative stress,whereas those whose controlimproved over the follow-up periodreported positive stress. Negativestressors included interpersonal con-flicts, death of a close tie, and dis-turbed behavior of someone close,

whereas positive stressors were eventssuch as engagement to be married,birth of a child, or a desired change inemployment (Figure 1).

Studies such as the one reportedabove have their limitations. Forexample, not all individuals perceivestressors in the same way; what is anegative stressor in one person’s lifemight actually be a positive one inanother’s, so the context in whichstress occurs is also important. Somepeople react to stressful events in away that makes them psychologicallyvulnerable, for example, they mayexperience feelings of hopelessness oranxiety, particularly in the context of social isolation or poverty. Othersmay respond to stress in positiveterms or as a “challenge,” or theymay feel better able to cope with thestress because they have several socialsupports or the support of a lovingfamily. It is easier to categorize majorstressors into those that are positiveand those that are negative; it is moredifficult for more minor stress or“hassles.” Long-term chronic difficul-ties are also important, but maychange in perceived level of severity ornegativity over time.

Findings from Smith’s study22 of women’s experiences of diabetes-relat-ed stress indicated that a wide varietyof factors were important, includingrelationships with other people(including health care professionals),the interaction between diabetes anddaily life and work, and fear of thefuture. Minor stressors and hassleswere seen as an integral part of livingwith diabetes in this study and were

Feature Article/Stress and Diabetes

7/23/2019 Stress and Diabetes a Review of the Links

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/stress-and-diabetes-a-review-of-the-links 3/7

12Diabetes Spectrum Volume 18, Number 2, 2005

related to both work and family life,which often took priority over themanagement of diabetes.

The impact of stressful experienceson diabetes is clearly varied and maydepend on other psychosocial factors.One of these is social support, andresearch has shown this may providea buffering effect in times of stress.13

Psychological support is also impor-tant. In a recent meta-analysis of ran-domized controlled trials, Ismail etal.23 concluded that people with type

2 diabetes who received behavioral-based diabetes education or psycho-logical interventions were likely toshow improvements in both glycemiccontrol and psychological distress.

The relationship between stressfulexperiences and metabolic control isthought to differ greatly among indi-viduals in terms of both the strengthand the direction of the relationship,24

and these differences have seriousimplications for the design of effectiveinterventions to reduce the impact of

stressors. Precisely how stressorsaffect glycemic control remains con-troversial, and there may be bothphysiological and behavioral path-ways between stressors and health sta-tus. The mechanisms through whichthis may take place may be direct(through physiological effects on theneuroendocrine system)25 or indirect(through alterations in health carepractices in times of stress).18,26 It is tothese pathways that we now turn.

BehaviorThe behavioral mechanisms throughwhich stressful experiences might

affect diabetes control are varied andoften complex. There are, of course,many different types of stress, thereare shorter- and longer-term stressors,and people may respond to these verydifferently. Difficulties in measure-ment such as those mentioned abovealso apply to measuring behavior. Atthe same time, differences in resourcessuch as social supports, ability tocope, and other psychosocial variableswill all affect both the response to andthe behavior resulting from stressful

experiences.Reactions to external stressors, forexample, feelings of anxiety ordepression, may lead to difficultieswith self-care manifested through lessphysical activity, poorer diet, or diffi-culties with medication taking.27,28

Experiences of stress may lead toother unhealthy behaviors, such assmoking, which in turn are linked topoor blood glucose control but alsoto a greater risk of developing dia-betes complications.29 Data from

Smith’s study22

indicated a range of behavior described as occurring inresponse to stress. These behaviorsranged from unhealthy lifestyle pat-terns associated with alcohol andtobacco consumption to increasedphysical activity and relaxation, suchas walking, yoga, swimming, medita-tion, and hypnotherapy.

One particular type of stress wasinvestigated in a Swedish study.Agardh et al.30 demonstrated thatwork stress, as indicated by low deci-

sion latitude (or fewer opportunitiesfor decision making), along with alow sense of coherence, significantly

increased risk for type 2 diabetes.Low sense of coherence is thought tonegatively affect people’s ability tocope with stressors31 and also to belinked to unhealthy lifestyle patternsthat could lead to poor health.

Research also supports the behav-

ioral link. Peyrot et al.32

found thatstress and coping affected glycemiccontrol by interfering with self-carepractices. Coping behavior was alsoshown to affect glycemic control in astudy of type 1 and type 2 diabetesthat used sophisticated statistical tech-niques to demonstrate a “network” of interlinked variables in relation to theachievement of treatment goals.33 Forexample, active coping behavior wasassociated with higher self-efficacyand greater satisfaction with doctor-

patient relationships. The researcherssuggested that their findings have clin-ical implications for diabetes carebecause coping behavior (a key factorin their analysis) was linked to self-care but could also be influenced bythe health care professionals involvedin that care. However, little work hasbeen carried out to try to implementthe findings of coping research intoclinical practice.34 Changes in clinicalpractice have usually involved behav-ioral interventions (task-oriented)rather than cognitive ones or haveonly included coping implicitly ratherthan explicitly.34

Diabetes-related distress may alsoaffect self-care behavior,35,36 asdemonstrated when the ProblemAreas in Diabetes (PAID) scale wasdeveloped.35 The scale covers negativeemotions related to living with dia-betes, for example, “feeling alonewith diabetes” and “worrying aboutthe future and the possibility of seri-ous complications.” Although oftenassociated with depression,36,37 dia-betes-related distress has been foundto be predictive of diabetes self-carebehavior as well as blood glucose con-trol.36,38

Depression and diabetes-relateddistress can occur together and canhave serious implications for the man-agement of diabetes, because thoseaffected may feel unable or unmoti-vated to carry out self-care behaviorssuch as blood glucose testing orhealthy eating. A different group of researchers in the United States hasidentified both diabetes-related stressand other stressors as important in

Feature Article/Lloyd et al.

Figure 1. Relationship between stress and glycemic control. From Ref. 21.

0

10

Improved RemainedFair

RemainedPoor

Deteriorated

30

20

70

80

60

40

50

% w

i t h e a c h t y p e o f s t r e

s s i n p a s t m o n t h Positive

(No SPS)

Other

Severe PersonalStressors

Differences between the groups significantly different P = 0.000.

7/23/2019 Stress and Diabetes a Review of the Links

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/stress-and-diabetes-a-review-of-the-links 4/7

124Diabetes Spectrum Volume 18, Number 2, 2005

predicting self-care behavior.27 If study participants reported, “My lifeis out of control because of my dia-betes” or “I have other problemsmore serious than diabetes,” theywere less likely to report attention todiet or exercise as part of their dia-

betes self-care.In summary, studies strongly sug-gest that stressful experiences have animpact on diabetes self-care behavior;however, there are many different fac-tors that may mediate this relation-ship. Before turning to the implica-tions for clinical practice, we considerthe physiological mechanisms behindstress and its impact on diabetes.

Physiological Mechanisms BehindStressful Experiences

Any stressful event might be judgedby people in different ways, based onfactors such as previous experience,psychological factors, and social influ-ences. An event that is seen by oneindividual as particularly threateningmight be seen as totally harmless byanother individual. However, when asituation is regarded as threatening,that is, seen as having the potential tocause harm to the individual, a specif-ic pattern of physiological responses iselicited, known as the stress responseor “fight/flight” response. This pat-tern of responses has developed as aresult of human evolution and isaimed at priming the individual foraction, so that the situation can bedealt with by either fighting or fleeingthe threat. The actions initiated by thecentral nervous system in response toa threat affect the entire body and areassociated with three different bodilysystems: the autonomic nervous sys-tem, the neuroendocrine system, andthe immune system.39,40

The autonomic nervous system isconcerned with the regulation of smooth muscle, cardiac muscle, andglands and regulates the functionsover which there is no conscious con-trol, such as cardiovascular function,digestion, and metabolism. It consistsof two distinct branches: the parasym-pathetic and the sympathetic nervoussystem, the latter being the most dom-inant in times of stress. The sympa-thetic system is involved with thepreparation of the body for action. Itincreases oxygen and nutrient suppliesto the muscles by increasing the bloodflow to the skeletal muscles and free-

ing glucose and lipids from its stores.It also prepares the immune system todeal with possible injury.

With regard to the effects of stresson the neuroendocrine system, theHPA axis is of considerable impor-tance.39 Upon encountering a threat or

a stressor, the hypothalamus secretescorticotropin-releasing factor, whichcauses the release of adrenocorti-cotropin. This in turn travels to theadrenal cortex, where it leads to thesecretion of glucocorticoid hormones,in particular cortisol.

Cortisol exerts considerable influ-ence over bodily functions, both whenthe body is at rest and during stress. Innormal circumstances, it is secretedaccording to a circadian (daily)rhythm, with cortisol levels highest in

the morning and lowest in the evening.However, exposures to stress stimulatethe HPA axis to release additionalamounts of cortisol to maintain home-ostasis and reduce the effects of stress.Cortisol influences a wide range of processes, including the breakdown of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins toprovide the body with energy. It alsohas an effect on bone and cell growthand may modulate salt and water bal-ance. Cortisol has an immunosuppres-sive effect and therefore plays a role inthe regulation of immune and inflam-matory processes.

That the central nervous systemcommunicates with and exerts aninfluence on the immune system isnow well established; brain lesionscan alter a variety of immune mea-sures, and both the autonomic and theneuroendocrine system have beenshown to influence the state of theimmune system.41 Because both theneuroendocrine and the autonomicsystem are influenced by psychosocialfactors, it follows that the immunesystem is also affected by such factors,although the precise nature of thesecomplex interactions remains to bedetermined.

Although there is still muchunknown about the effects of acutestress on the immune system and stud-ies have been limited in the number of immune parameters studied, onereview42 revealed that stress influencesboth circulating cell numbers and thefunction of immune cells. The cellsgenerating the immune defense aregenerally known as white blood cellsand consist of several subgroups

including the lymphocytes (-cells, T-cells, and natural killer cells), whichhave received much attention in stressresearch.41

Although research into the effectsof stress continues, it seems clear thatthere is a range of responses to stress-

ful experiences, both physiologicaland behavioral/emotional. The finalsection of this article focuses on theimplications of stress research forpractice in the care of individuals withdiabetes.

Implications For Practice: StressManagementIn addition to the physiologicalimpact that stress has on glycemia,research has shown that stress inter-feres with the ability to self-manage

diabetes. Doing everyday self-caretasks, such as monitoring glucose fre-quently, following a meal plan, andcorrectly preparing or remembering totake insulin or oral medications at theright time, is difficult during times of stress. Moreover, diabetes self-man-agement tasks themselves may becomea source of stress. Learning to preventand control the negative responses tostress is helpful, particularly if thecauses are relatively permanent. Forexample, if cooking dinner, bathingchildren, and doing laundry constitutea typical stressful evening, that stressis a relatively permanent part of lifefor several years and must be dealtwith accordingly.

Assessment of stress levels in prac-tice is a relatively underdevelopedarea. One approach is to identify thoselife events during the previous yearthat typically act as stressors. Using ascale such as the Recent Life ChangesQuestionnaire43 or the Revised SocialReadjustment Rating Scale,44 individu-als identify events that have occurredin their life from a list that includesbirths, deaths, marriage, retirement,social issues, financial worries, work-related stress, and so forth. Theweighted ratings provide the basis foran overall score that can be comparedto norms. However, these scales arerather long and take some time tocomplete, which may not always beappropriate in a practice setting.

Polonsky45 describes a diabetes-spe-cific exercise to help people with dia-betes develop an understanding of therelationship between stress and bloodglucose levels. In this exercise, individ-

Feature Article/Stress and Diabetes

7/23/2019 Stress and Diabetes a Review of the Links

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/stress-and-diabetes-a-review-of-the-links 5/7

12Diabetes Spectrum Volume 18, Number 2, 2005

uals rate their perceived stress eachevening on a 0–10 Likert scale andrecord their glucose levels beforebreakfast and dinner and at bedtime.The individual then looks for bloodglucose level patterns for days whenperceived stress is high, medium, and

low. The premise behind this exerciseis that those individuals whose bloodglucose levels are sensitive to stressmay be more sensitive to stress man-agement strategies. Although valida-tion data are not available, individualsmay find this approach helpful inunderstanding and managing stress-related aberrant glucose readings.Finally, surveys tools, such as the indi-vidual items on the PAID scale thatmeasure diabetes-related distress, mayalso reflect accumulated stress result-

ing from living with diabetes. PAIDscores are associated with A1C lev-els.35,36,38

Clinicians must take care to differ-entiate stress response from depres-sion and anxiety. Depression is morecommon in diabetes than in the gener-al population.46,47 Although bothunder-diagnosed and under-treat-ed,48,49 depression is responsive toboth medication and psychotherapy.Tools such as the Beck DepressionInventory50 or the Hospital Anxietyand Depression Scale51 are useful inscreening for depression. Asking sim-ple questions such as, “During thepast month, have you been botheredby feeling down, depressed, or hope-less?” and “During the past month,have you been bothered by little inter-est or pleasure in doing things?” canbe as successful as surveys whenscreening for depression.52

Three approaches to stress manage-ment go hand in hand, albeit withsome overlap: 1) when possible,removing or minimizing the source of stress, 2) changing the response to thestressful situation, and 3) modifyingthe longer-term effects of stress. Someinterventions directly target peoplewith diabetes in order to prevent dia-betes-related stress and improve quali-ty of life or glycemia.

1. Remove or minimize the source of stress.Time management and organizationaltechniques may reduce small stressorsthat often compound until a crescen-do is reached. Self-help books53,54 maybe useful for patients to find success-

ful ways to put structure in their livesand manage their time and life stres-sors. Minimizing the source of stress ishelpful. For example, if repetitivenoise at work is causing stress, onesolution could be substituting whitenoise for the repetitive noise by softly

playing relaxing classical music.Setting up a meeting with the employ-er or coworkers to get help with one’sworkload may also alleviate stress.Often, the most difficult challenge isactually identifying the source of stress and separating that source fromthe responses to stress. Effective prob-lem-solving strategies are importantfor minimizing the source of stress.

Diabetes-specific approaches thatmay help individuals cope better withdiabetes include setting specific, realis-

tic self-management goals. Many indi-viduals set global vague goals thatmay serve to exacerbate stress. “Loseweight,” “Take better care of my dia-betes,” and “Improve my glycemiccontrol” are examples of vagueunhelpful goals. Realistic, measurable,and achievable goals specifically stat-ing the measurement criteria that indi-cate success are more helpful as moti-vators. Examples of realistic, measur-able goals are, “I will walk 20 min-utes each day on Monday,Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday at5:00 p.m.;” “I will drink diet colainstead of cola with sugar;” and “Iwill lose 6 lb over the next 9 weeks byfollowing my meal plan and increas-ing my walking to 30 minutes, 5 daysper week.” Evaluation does not neces-

sarily have to focus on whether a goalis met, but rather on how successfulone’s effort has been in trying toachieve it. Thus, instead of “No, I didnot reach my target A1C,” evaluationwould be “My A1C has improved by0.5 percentage points, thus, I am

about half way to my first goal of a1–percentage point improvement.”

2. Change the response to stress.Most stress management techniquesemphasize changing the response tostress. When the response to chronicor acute stress results in rage and reac-tive behavior, a thought-stopping andreflective technique can be helpful inpreventing negative consequences of the impulsive behaviors associatedwith anxiety and rage (Table 1).

Other approaches involve learninghow to induce a more relaxed feeling.Benson’s relaxation response,55 first

reported as a means to lower bloodpressure, can be useful in inducingrelaxation quickly in times of stress,for example, while driving in traffic,or before taking an exam. Practicingthe relaxation response is extremelyimportant because the technique isdifficult to learn. However, oncelearned, the relaxation responsequickly brings about the physiologicalresponses associated with relaxation.

3. Modifying the longer-term effectsof stress.Other approaches to stress that maybe useful for individuals with diabetesinclude using distraction and involve-

Feature Article/Lloyd et al.

STOP To interrupt a negative spiral of anger, say “stop” out loudor to yourself.

BREATHE Take several deep breaths, exhaling slowly.

REFLECT Think about the situation and what could happen if . . . If you choose to act in anger, what could happen? What areall the negative things that may happen? What would youaccomplish? Be thorough and reflect on the consequences of your actions, how your actions will affect others, how theywill affect you in the long term.

CHOOSE Based on your reflection above, decide how you will act.

THEN ACT Your actions are then based on rational thought rather thanon anger. The actions may not change, but what is differentis that you are in control and have thought about the conse-quences of your actions.

Table 1. A Thought-Stopping Strategy for Acute Rage

7/23/2019 Stress and Diabetes a Review of the Links

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/stress-and-diabetes-a-review-of-the-links 6/7

126Diabetes Spectrum Volume 18, Number 2, 2005

ment in pleasurable activities that helpto minimize the influence of stress-producing activities. (For other exam-ples, see Table 2.) For example, activeparticipation in a hobby (even asedentary one) or exercise programcan help combat stress. Typically pas-

sive activities, such as watching televi-sion, may not help alleviate stress,although attending a concert, theaterperformance, or movie with friendscan have beneficial effects as a distrac-tion. If one is not able to put asideworries from work, then distractionmay be effective.

If a person with diabetes is experi-encing severe stress, referral to a men-tal health professional may be themost effective approach.

Reports from research investigating

the effect of stress management onglycemic control have been inconsis-tent.56–60 Several of these studies wereunderpowered, and others had designproblems. However, recent reportshave shown that stress managementmay affect diabetes and its treatment.In a small study with a pre-/post-designand no control group,61 20 study par-ticipants demonstrated improvedglycemic control and state and traitanxiety scores after 12 weeks of treat-ment with an anti-anxiety medication(fludiazepam). Surwit et al.14 used arandomized, controlled design to inves-

tigate the use of stress managementtechniques for groups of type 2 dia-betes patients. They found that thoseusing stress management had a smallimprovement in A1C (0.5 percentagepoints) at the 1-year follow-up com-pared to those who were not. Although

Boardway et al.62

found that adoles-cents receiving stress managementimproved stress levels but not glycemiccontrol or adherence, evidence nowexists that stress management trainingmay potentiate intensive treatment. Foradolescents enrolled in an intensive dia-betes management clinic, Grey et al.63,64

demonstrated that preventive strategiessuch as teaching coping skills to adoles-cents with type 1 diabetes in order tobetter prepare them for stressful lifeevents can lead to improvements in

both glycemic control and quality of life and that the improvement wasmaintained over time.

In summary, research has indicatedthat stressful experiences have animpact on diabetes. Stress may play arole in the onset of diabetes, it canhave a deleterious effect on glycemiccontrol and can affect lifestyle.Emerging evidence strongly suggests,however, that interventions that helpindividuals prevent or cope with stresscan have an important positive effecton quality of life and glycemic con-trol. The clinical implications of thisresearch illustrate the need for greaterunderstanding of the effects of stress,as well as a serious acceptance of theneed for psychosocial support for peo-ple in this predicament.

References1Willis T: Pharmaceutice rationalis or an exerci-tation of the operations of medicines in humanbodies. In The Works of Thomas Willis. London,Dring, Harper, Leigh, 1679

2Thernlund GM, Dahlquist G, Hansson K,Ivarsson SA, Kudvigsson, Sjoblad S, Hagglof B:Psychological stress and the onset of IDDM inchildren. Diabetes Care 18:1323–1329, 1995

3Kisch ES: Stressful events and the onset of dia-betes mellitus. Isr J Med Sci 21:356–358, 1985

4Vialettes B, Ozanon JP, Kaplansky S, FarnarierC, Sauvaget E, Lassman-Vague V, Vague P:Stress antecedents and immune status in recentlydiagnosed type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetesmellitus. Diabetes Metab 15:45–50, 1989

5Kawakami N, Araki S, Takatsuka N, ShimizuH, Ishibashi H: Overtime, psychosocial workingconditions, and occurrence of non-insulin depen-dent diabetes mellitus in Japanese men. J Epidemiol Community Health 53:359–363,1999

6Mooy JM, De Vries H, Grootenhuis PA, BouterLM, Heine RJ: Major stressful life events in rela-tion to prevalence of undetected type 2 diabetes.Diabetes Care 23:197–201, 2000

7Bjorntop P: Body fat distribution, insulin resis-tance, and metabolic diseases. Nutrition13:795–803, 1997

8Bjorntop P: Visceral fat accumulation: the miss-

ing link between psychological factors and car-diovascular disease? J Intern Med 230:195–201,1991

9Bottazo GF, Pujol-Borrell R, Gale E: Etiology of diabetes: the role of autoimmune mechanisms. InThe Diabetes Annual . Alberti KG, Krall LP, Eds.Amsterdam, Elsevier/North Holland, 1985, p.16–52

10Cosgrove M: Do stressful life events cause type1 diabetes? Occup Med 54:250–254, 2004

11Littorin B, Sundkvist G, Nystrom L, Carlson A,Landin-Olsson M, Ostman J, Arnqvist HJ, BjorkE, Blohme G, Bolinder J, Eriksson JW, SchierstenB, Wibell L: Family characteristics and life events

before the onset of autoimmune type 1 diabetesin young adults. Diabetes Care 24:1033–1037,2001

12Delamater AM, Cox DJ: Psychological stress,coping, and diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum7:18–49, 1994

13Viner R, McGrath M, Trudinger P: Familystress and metabolic control in diabetes. ArchDis Child 74:418–421, 1996

14Surwit RS, van Tilburg MA, Zucker N,McCaskill CC, Parekh P, Feinglos MN, EdwardsCL, Williams P, Lane JD: Stress managementimproves long-term glycemic control in type 2diabetes. Diabetes Care 25:30–34, 2002

15DeVries JH, Snoek FJ, Heine RJ: Persisitentpoor glycaemic control in adult Type 1 diabetes:a closer look at the problem. Diabet Med 21:1263–1268, 2004

16The DCCT Research Group: The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the develop-ment and progression of long-term complicationsin insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 329:977–986, 1993

17Goetsch VL, VanDorsten B, Pbert LA, UllrichIH, Yeater RA: Acute effects of laboratory stresson blood glucose in non-insulin-dependent dia-betes. Psychosom Med 55:492–496, 1993

18Hanson CL, Henggeler SW, Burghen GA:Model of associations between psychosocial vari-ables and health-outcome measures of adoles-cents with IDDM. Diabetes Care 10:752–758,1987

19Delamater A, Kurtz SM, BubbJ, White NH,Santiago JV: Stress and coping in relation tometabolic control of adolescents with type 1 dia-betes. J Dev Behav Pediatr 8:136–140, 1987

20Lloyd CE, Robinson N, Stevens LK, Fuller JH:The relationship between stress and the develop-ment of diabetic complications. Diabet Med 8:146–150, 1990

21Lloyd CE, Dyer PH, Lancashire RJ, Harris T,Daniels JE, Barnett AH: Association betweenstress and glycaemic control in adults with type 1(insulin dependent) diabetes. Diabetes Care22:1278–1283, 1999

Feature Article/Stress and Diabetes

Changing stress-producingsituations• Time management• Improved organization skills• Learning problem-solving skills

Changing the physiologicalresponse to stress• Stop, Breathe, Reflect, and

Choose (Table 1)• Relaxation with or without tapes• Deep muscle relaxation• Head-to-toe relaxation• Pleasant scenes• Breath-focused relaxation• Yoga, Tai Chi, meditation• Hot baths, scented candles

De-emphasizing stress withdistractions• Hobbies• Attending pleasant activities,

such as theater, movies, concerts

Table 2. Useful Interventionsfor Managing Stress

7/23/2019 Stress and Diabetes a Review of the Links

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/stress-and-diabetes-a-review-of-the-links 7/7

12Diabetes Spectrum Volume 18, Number 2, 2005

22Smith J: The enemy within: stress in the lives of women with diabetes. Diabet Med 19 (Suppl.2):98–99, 2002

23Ismail K, Winkley K, Rabe-Hesketh S:Systematic review and meta-analysis of random-ized controlled trials of psychological interven-tions to improve glycaemic control in patientswith type 2 diabetes. Lancet 363:1589–1597,

200424Kramer JR, Ledolter J, Manos GN, BaylessML: Stress and metabolic control in diabetesmellitus: methodological issues and an illustrativeanalysis. Ann Behav Med 22:17–28, 2000

25Konen JC, Summerson JH, Dignan MB: Familyfunction, stress and locus of control: relation-ships to glycaemia in adults with diabetes melli-tus. Arch Fam Med 2:393–402, 1993

26Lloyd CE, Wing RR, Orchard TJ, Becker DJ:Psychosocial correlates of glycemic control: thePittsburgh Epidemiology of DiabetesComplications (EDC) Study. Diabetes Res ClinPract 21:187–195, 1993

27Albright TL, Parchman M, Burge SK, theRRNeST Investigators: Predictors of self-carebehavior in adults with type 2 diabetes: anRRNeST Study. Fam Med 33:354–360, 2001

28Lin EHB, Katon W, Von Korff M, Rutter C,Simon GE, Oliver M, Ciechanowski P, LudmanEJ, Bush T, Young B: Relationship of depressionand diabetes self-care, medication adherence, andpreventive care. Diabetes Care 27:2154–2160,2004

29Spangler JG, Summerson JH, Bell RA, KonenJC: Smoking status and psychosocial variables intype 1 diabetes mellitus. Addict Behav 26:21–29,2001

30Agardh EE, Ahlbom A, Andersson T, EfendicS, Grill V, Hallqvist J, Norman A, Ostenson CG:Work stress and low sense of coherence is associ-ated with type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Swedishwomen. Diabetes Care 26:719–724, 2003

31Antonovsky A: Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and StayWell . San Francisco, Calif. Jossey-Bass, 1987

32Peyrot M, McMurry JF, Kruger DF: A biopsy-chosocial model of glycemic control in diabetes:stress, coping and regimen adherence. J HealthSoc Behav 40:141–158, 1999

33Rose M, Fliege H, Hildebrandy M, Schirop T,

Klapp BF: The network of psychological vari-ables in patients with diabetes and their impor-tance for quality of life and metabolic control.Diabetes Care 25:35–42, 2002

34De Ridder D, Schreurs K: Developing interven-tions for chronically ill patients: is coping a help-ful concept? Clin Psychol Rev 21:205–240, 2001

35Polonksy WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, WelchG, Jacobson AM, Aponte JE, Schwartz CE:Assessment of diabetes-related distress. DiabetesCare 18:754–760, 1995

36Welch GW, Jacobson AM, Polonsky WH: The

Problem Areas In Diabetes scale: an evaluationof its clinical utility. Diabetes Care 20:760–766,1997

37Skinner TC, Cradock S, Meekin D, Cansfield J:Routine screening for depression and diabetesemotional distress: a pilot study. Diabet Med 19(Suppl.):A345, 2002

38Weinger K, Jacobson AM: Psychosocial and

quality of life correlates of glycemic control dur-ing intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. Patient Educ Couns 42:123–131, 2001

39Willemsen G, Lloyd C: The physiology of stressful life experiences. In Working for Health.Heller T, Muston R, Sidell M, Lloyd C, Eds.London, Open University/Sage, 2001

40Kiecolt-Glaser JK, McGuire L, Robles TF,Glaser R: Psychoneuroimmunology: psychologi-cal influences on immune function and health. J Consult Clin Psychol 70:537–547, 2002

41Staines N, Brostoff J, James K: Introducing Immunology. 2nd ed. St Louis, Mo., Mosby,

199442Herbert TB, Cohen S: Stress and immunity inhumans: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med 55:364–379, 1993

43Miller MA, Rahe RH: Life changes scaling forthe 1990s. J Psychosom Res 43:279–292, 1997

44Hobson CJ, Delunas L: National norms andlife-event frequencies for the Revised SocialReadjustment Rating Scale. Int J Stress Manag 8:299–314, 2001

45Polonksy WH: Diabetes Burnout . Alexandria,Va., American Diabetes Association, 1999

46Lloyd CE, Dyer PH, Barnett AH: Prevalence of

symptoms of depression and anxiety in a dia-betes clinic population. Diabet Med 17:198–202,2000

47Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE,Lustman PJ: The prevalence of comorbid depres-sion in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis.Diabetes Care 24:1069–1078, 2001

48Perez-Stable EJ, Miranda J, Munoz RF, YingYW: Depression in medical outpatients: under-recognition and misdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med 150:1083–1088, 1990

49Kovacs M, Obrosky DS, Goldston D, Drash A:Major depressive disorder in youths with IDDM:

a controlled prospective study of course and out-come. Diabetes Care 20:45–51, 1997

50Beck AT, Steer RA: Internal consistencies of theoriginal and revised Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol 40:1365–1367, 1984

51Zigmond AS, Snaith RP: The Hospital Anxietyand Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67:361–370, 1983

52Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, BrownerWS: Case-finding instruments for depression:two questions are as good as many. J Gen InternMed 12:439–445, 1997

53Morganstern J: Organizing From the InsideOut . New York, Henry Holt, 1998

54Morganstern J: Time Management From theInside Out . New York, Henry Holt, 2000

55Benson H, Stuart EM: The Wellness Book: TheComprehensive Guide to Maintaining Healthand Treating Stress Related Illness. New York,Simon & Schuster, 1992

56Stenstrom U, Goth A, Carlsson C, AnderssonPO: Stress management training as related toglycemic control and mood in adults with type 1diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 60:147–152, 2003

57Bradley C: Contributions of psychology to dia-betes management. Br J Clin Psychol 33:11–21,1994

58Aikens J, Kiolbasa TA, Sobel R: Psychologicalpredictors of glycemic change with relaxationtraining in non-insulin-dependent diabetes melli-tus. Psychother Psychosom 66:302–306, 1997

59Lane JD, McCaskill CC, Ross SL, Feinglos

MN, Surwit RS: Relaxation training forNIDDM: predicting who may benefit. DiabetesCare 16:1087–1094, 1993

60Mendez FJ, Belendez M: Effects of a behavioralintervention on treatment adherence and stressmanagement in adolescents with IDDM.Diabetes Care 20:1370–1375, 1997

61Okada S, Ichiki K, Tanokuchi S, Ishii K,Hamada H, Ota Z: Improvement of stressreduces glycosylated haemoglobin levels inpatients with type 2 diabetes. J Int Med Res23:119–122, 1995

62Boardway RH, Delamater AM, Tomaskowsky J, Gutai JP: Stress management training for ado-

lescents with diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol 18:29–45, 1993

63Grey M, Boland EA, Davidson M, Yu C,Tamborlane WV: Coping skills training foryouths with diabetes on intensive therapy. Appl Nurs Res 12:3–12, 1999

64Grey M, Boland EA, Davidson M, Li J,Tamborlane WV: Coping skills training foryouth with diabetes mellitus has long-lastingeffects on metabolic control and quality of life. J Pediatr 137:107–113, 2000

Cathy Lloyd, PhD, is a senior lecturerin Health & Social Care at the OpenUniversity in Milton Keynes, U.K.

Julie Smith, BSc, RGN, is an academ-ic program leader in evidence-based clinical practice at the HomertonSchool of Health Studies at Peterborough District Hospital inPeterborough, U.K. and KatieWeinger, EdD, RN, is an investigatorat the Joslin Diabetes Center and anassistant professor at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Mass.

Feature Article/Lloyd et al.