Strategic Fools Electoral Rule Choice Under Extreme Uncertainity

Transcript of Strategic Fools Electoral Rule Choice Under Extreme Uncertainity

www.elsevier.com/locate/electstud

Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

Strategic fools: electoralrule choice under extreme uncertainty

Josephine T. Andrews�, Robert W. Jackman

Department of Political Science, University of California, Davis, One Shields Avenue,

Davis, CA 95616, USA

Abstract

We compare patterns of electoral rule choice in two periods, that following the First WorldWar in Western Europe and that following the end of the Cold War in Central and EasternEurope. Heretofore, scholars have studied these two instances of electoral rule choice separately

and have come to quite different conclusions about the implications of strategic behavior of therelevant actors. In the case of early 20thCenturyWesternEurope,Rokkan and laterBoix cast thechoice of electoral rules as a result of coordinated strategic behavior by established parties inreaction to increasing support for new parties of the left. In contrast, recent analyses of the post-

Cold War period in Central and Eastern Europe suggest that while all political actors actedstrategically, an extreme lack of information prevented them from making choices that servedtheir self-interest in the long run. Indeed, many party leaders supported electoral rules that later

eliminated them from politics. We argue that uncertainty was a major factor in both periods ofelectoral rule design, so that political elites often made serious miscalculations of the effect ofparticular electoral rules on their own future success. A reanalysis of the Boix data suggests that

efforts to explain the choice of electoral rules as a coordinated response by established parties toelectoral threat must be viewedwith skepticism, since uncertaintymade success or failure almostimpossible to predict. Instead, any strategic behaviorwas short-term at best, reflecting the largest

party’s most recent experience in the preceding election.� 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Electoral rule; Strategic behavior; Boix data

�Corresponding author. Tel.: C1-530-754-8108.

E-mail addresses: [email protected] (J.T. Andrews), [email protected] (R.W. Jackman).

0261-3794/$ - see front matter � 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2004.03.002

66 J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

1. Introduction

The recent wave of democratization in Central and Eastern Europe has refocusedattention on the choice of electoral institutions. The emerging view takes this choiceto be the product of strategic decisions by key political actors operating underuncertainty (Przeworski, 1991; Lijphart, 1992; Geddes, 1996; Shvetsova, 2003). Incontrast, research on the electoral reforms that occurred in Western Europesurrounding the First World War has cast the choice of electoral institutions as thepredictable product of strategic calculations of established parties given the votereceived by rising socialist forces (for the classic statement, see Rokkan, 1970, andfor a recent statement, see Boix, 1999). Among other things, this predictabilityimplies that strategic calculations underlying electoral choices in the early 20thCentury involved little uncertainty about the political consequences of alternativeinstitutional arrangements.

Our purpose is to show that the choice of electoral systems in the two periods wasgoverned by the same logic, one in which strategic actors sought to maximize theirlegislative presence under conditions of extreme uncertainty. Given this fact, thesafest choice typically involved some form of proportional representation. Further,political actors have had mixed success at best in choosing electoral rules thatsubsequently optimized their electoral performance. In many cases, particular partiesappear (at least in retrospect) to have been strategically foolish, in the sense that therules they approved ended up eliminating them from politics.

2. The issues

Like institutional change more generally, electoral reform is a rare event, sincethose in a position to initiate reform themselves assumed power under existinginstitutional arrangements (see, e.g. Cox, 1997, p. 18). For political actors to engagein reform of the procedures by which they won in the first place, they must come tobelieve either that existing arrangements will adversely affect their future prospectsfor winning, or that they face considerable uncertainty, or both. This, in turn, is mostlikely when winners face a profound shift in the composition of the electorate and/orthe political arena more broadly arising from major political transformations. Just asevents in Central and Eastern Europe in the late 20th Century constituted a majortransformation, so too did the events surrounding the First World War in much ofWestern Europe. Such transformations are by definition extraordinary, and un-certainty becomes endemic for all actors.

3. Studies of the recent period

Studies of the adoption of electoral rules in post-communist Central and EasternEurope emphasize the ways that uncertainty undermines the effectiveness of thestrategic behavior of all parties (see, e.g. Remington and Smith, 1996; Moraski and

67J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

Loewenberg, 1999; Moser, 2001; Kaminski, 2002; Shvetsova, 2003). All actors,whether favoring the status quo or not, support electoral rules that they believe willoptimize their legislative presence (see, e.g. Benoit, 2004). However, miscalculationsare frequent, if not the norm, given informational shortcomings.

Typically, in the recently formed democracies of Central and Eastern Europe, newelectoral rules were first negotiated in round table settings that included politicalparties present during the time of transition (Geddes, 1996; Elster et al., 1998).Newly elected legislatures often further amended, or changed outright, these initialchoices. In analyzing the strategic interests and preferences of parties at either theround table negotiations or in legislative decision-making, scholars have stressed thediscrepancies between anticipated and realized consequences of particular rules.Among other things, the post-communist transitions involved substantial volatilityin partisan electoral support as well as in the number and ideological characteristicsof political parties. Further, opinion polls revealed dramatic and frequent shifts inpublic support for political parties, and key political actors had limited historicalelectoral experience on which to base their calculations. All these factors increasedthe odds of strategic mistakes, and the ‘‘evidence systematically shows that . post-communist institution-makers adopted the rules that they themselves would havewanted to change almost immediately’’ (Shvetsova, 2003, p. 201).

Analyses of the choice of electoral rules in post-communist countries underscore theways in which the quality of strategic decisions hinges on the information available tothe key actors at the time (Shvetsova, 2003, pp. 193–194). InKaminski’s words, ‘‘Thereare two reasons that may explain a disastrous outcome for a rational player ora stunning success for a fool. First, the model used by a player may be inadequate forthe empirical decision problem.. Second, when uncertainty is involved, a surprising‘move of Nature’ may turn a smart decision into a bad outcome or a stupid decisioninto a glorious victory’’ (2002, p. 334). Consider the effect of uncertainty over threeessential kinds of information needed to predict the potential effect of electoral ruleson electoral outcomes. These are: (1) the number of parties that will compete in futureelections; (2) the preferences of voters over these parties; and (3) the effect of theelectoral rules themselves, especially institutional details such as the district magnitudeor electoral threshold. Observe the interdependencies among these three types ofinformation. For example, unless actors know the number of parties that will competein future elections, they cannot gauge voter preferences. Similarly, absent informationabout voter preferences, they cannot calculate the effect that the electoral rules willhave on electoral results, even if they are knowledgeable about the effect of a particularset of rules on election outcomes. Thus, uncertainty over any of these three particulartypes of information leads to more generalized uncertainty over the relationshipbetween electoral rules and electoral outcomes.

The interdependencies between these three types of information mean that actorsface considerable uncertainty even if they are quite well-informed on two of the threecounts (as is more likely in contemporary well-established democracies). For example,a change in electoral rules may lead to the entry of new parties or the demise of oldones. That is, the choice of rules influences the number of parties, which in turnchanges voter preferences and electoral results. In addition, while polling results may

68 J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

be accurate on a certain day given a certain set of parties, if the set of parties changes,so too do voter preferences. Finally, beyond a general understanding of the differenteffects of proportional representation (PR) versus single-member district plurality(SMDP), even experts’ understanding of the effect of complex electoral rules onelectoral outcomes is quite limited, and the politicians designing post-communistelectoral systems were simply not aware of the important effects of features such asthe electoral threshold and district magnitude (Remington and Smith, 1996, pp. 1259–1261; Shvetsova, 2003, pp. 203–206). Thus, given the conditional impact of eachseparate source of uncertainty along with the general limitations of expert under-standing of the impact of electoral rules, uncertainty always plagues the choice ofelectoral rules. It follows that there can be no simple linear relationship betweenelectoral rule choice and electoral performance.

This is not to imply that political actors do not behave strategically; in fact, they doso to the best of their ability. As has often been observed (e.g. Geddes, 1996; Benoit,2004), political parties in the late 20th Century, whether status quo communists or newopposition parties, supported electoral rules that they believed were best for them.Unfortunately, uncertainty made it impossible for any political actor to predict howparticular electoral designs would affect party support. Remington and Smith tell usthat the political actors responsible for writing Russia’s electoral law were themselveswell-aware of this uncertainty. ‘‘As best we can determine, then, calculating politiciansstruggled with what they realized was inadequate information for making the choicesthey faced’’ (1996, p. 1261). It is not hard to find examples from the recent experience inEastern Europe of the three types of uncertainty reviewed above: (1) uncertainty overthe number of political parties; (2) uncertainty over the preferences of voters; and(3) uncertainty over the impact of electoral rules.

3.1. Uncertainty over the number of political parties

In every new post-communist democracy, political actors were unable to predicthow many parties would compete in the first elections. In Poland, one of the mostsevere cases of such uncertainty, parties other than the former communist party didnot exist prior to the first election, and the number and even names of many of thetens of political parties that competed in the first election were not known until theOctober 1991 election itself. In Russia, where the number of parties that competed inthe party list contest was only thirteen, the final determination of those parties thatwould, in fact, compete was not made until November, 1993, just 1 month before theelection itself (White et al., 1997). In Hungary, where nine political parties existedprior to the first competitive election, there was a degree of predictability lacking inPoland and Russia; nevertheless, several additional parties joined these in competingfor seats in the 1990 election.

3.2. Uncertainty over the preferences of voters

Party leaders had little reliable information about the preferences of voters.Although public opinion polls were taken in some countries, the results of these polls

69J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

were notoriously inaccurate. Because the field of parties competing was in constantflux, polls could not be accurate. But, the most serious source of inaccuracy was thevolatility of voters’ opinions. In one of the best surveys of voter opinion in post-communist elections, Colton (2000) records extraordinary shifts in voter preferencesover the course of several weeks leading up to the 1995 parliamentary and 1996presidential elections in Russia. The acute shifts in voters’ choices between formercommunist parties and new right-reformist parties from election to election in manyof the post-communist countries attests to the continuing lack of voter identificationwith particular parties or even ideologies.

3.3. Uncertainty over the impact of electoral rules

In dramatic support of the assertion that under conditions of uncertainty,political actors have difficulty predicting the outcomes of different institutionalarrangements (Przeworski, 1991, p. 85), there were political parties in all post-communist countries that supported electoral rules that eliminated them frompolitics (Shvetsova, 2003).

4. Electoral choice and uncertainty

Given a high level of uncertainty, it is rational for parties to prefer an electoralsystem that best ensures their future survival. Scholars have suggested that pro-portional representation is a safer choice for a party that is not certain what share ofthe vote it will receive, especially if it is unsure whether it can win a plurality of thevote (Przeworski, 1991; Lijphart, 1992; Geddes, 1996). Empirically, we know thatproportional electoral systems encourage more parties than do single memberdistrict plurality systems (Duverger, 1954; Lijphart, 1994; Cox, 1997).

Shvetsova models formally the effect of uncertainty on electoral rule choice (2003,pp. 194–199). In her model, three states of the world are possible: (1) one in which nothird party can succeed; (2) one in which only one new party can succeed; and (3) onein which several new competitors can succeed. Depending on the actors’ assessmentsof the probability of each of these states of the world occurring, the ‘rational’ choiceof electoral system engineers will be either PR, SMDP, or a compromise system thatincludes both PR and SMDP, a so-called mixed system. Her model predicts that inthe majority of scenarios, actors will choose either PR or a mixed electoral systeminvolving both proportional and single member district components (Shvetsova,2003, Fig. 5).

This may help explain why only a small minority of the world’s democraciesemploy single member district electoral systems. As Cox (1997, Table 3.2) shows, ofthe 52 democracies with populations of more than one million in 1990, just one-fourth elect their national representatives exclusively in single member districts.About three-fourths of the world’s democracies elect their national representativesfrom multi-member districts, using either some version of proportional representa-tion, a mixed system in which lists are used to ensure a more proportional result, or

70 J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

an alternative multi-member district system. Among the new democracies that haveemerged (or re-emerged) in the past 15 years, none has adopted a single memberdistrict electoral system unless it has done so as part of a mixed system. That theelectoral system of choice for most of the world’s democracies involves some form ofproportional representation provides compelling evidence of the impact ofuncertainty on electoral choice.

Given this, the almost universal choice of some form of proportional repre-sentation in those democracies in which electoral reform was seriously entertained inthe years surrounding the First World War is unlikely to represent an informedresponse by established parties. It is instead more profitably cast as the best choice ofall parties operating under uncertainty. We turn now to the standard account ofelectoral choice in the first half of the 20th Century.

5. Studies of the early period

As we have already observed, in his influential analysis of the choices of electoralrules in early 20th Century Western Europe, Rokkan also emphasized the strategicconcerns generated by the expansion of the suffrage and appearance of new partiesof the left. ‘‘The rising working class wanted to lower the thresholds of repre-sentation in order to gain access to the legislatures, and the most threatened of theold-established parties demanded PR to protect their position against the new wavesof mobilized voters created by universal suffrage’’ (Rokkan, 1970, p. 157). Accordingto Rokkan, as the proportion of the electorate that supported the established partiesdecreased, those parties became more likely to support a reformed electoral systemthat would ensure their future survival. Thus, proportional representation wasadopted because it was in the interest of established political actors to do so.

Building on Rokkan’s work, Boix (1999) has analyzed the choice of electoralsystems in the set of countries that experienced at least a period of democraticgovernment during the interwar years (1919–1939) after the general introduction ofadult suffrage. In the principal part of his analysis, he characterizes the strategiccalculations of party leaders as follows:

As the electoral arena changes (due to the entry of new voters or a change invoters’ preferences), the ruling parties modify the electoral system, depending onthe emergence of new parties and the coordinating capacities of the old parties.When the new parties are strong, the old parties shift from plurality/majority toproportional representation if no old party enjoys a dominant position, but theydo not do this if there is a dominant old party. When new entrants are weak,a system of non-proportional representation is maintained, regardless of thestructure of the old party system (Boix, 1999, p. 609).

Change in electoral rules is cast as a strategic response by established elites to thechanging political arena. According to this argument, established parties favored thestatus quo until events convinced them that existing electoral laws allowed a newchallenger to displace them, at which point they moved preemptively to support

71J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

a reformed electoral regime to minimize their political losses. In this view, establishedparties acted strategically – coordinating their actions when necessary – to maximizeor preserve their legislative strength in light of significant changes to the distributionof preferences and number of political parties.

The argument is appealing in that it appears to identify the appropriate decision-makers as well as to provide a consistent and rational explanation of variation inchoice of electoral rules. When established party leaders judge their hold on majoritysupport to be waning, they wisely select proportional representation. If they believetheir hold on majority support is not threatened, they maintain a single memberdistrict system.

But this account of electoral choice as a predictable function of elite behaviorhinges on two tacit assumptions. First, and most notably, it presumes that thoseelites possessed sufficient information to be able to gauge accurately future voterpreferences and the number of political parties. The role of uncertainty in thestrategic calculations of party leaders is completely discounted. Second, the explana-tion implicitly assumes that political elites at the time operated in a Duverger-styleenvironment, where the choices were between a form of SMDP rule and some formof PR. However, the status quo in continental Europe before the First World Warinvolved majority rather than plurality rules, typically with provisions for runoffelections.

With the benefit of hindsight, the consequences of electoral reform in the earlypart of the 20th Century may seem to have been preordained. However, as we havealready emphasized, the political events surrounding the First World War cul-minating in full adult suffrage constituted a major political transformation, and weshould not minimize the uncertainty this transformation generated for the keypolitical actors at the time.

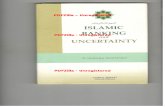

Consider the expansion of the suffrage. Between 1900 and 1925, the size of theelectorate doubled or trebled in nine major European sovereign states (Bartolini,2000, pp. 216–217, 584–588).1 As shown in Fig. 1, in all but one of these cases, theexpansion was abrupt, and occurred around the time of the First World War. Thetransformation generated by this massive and sudden influx of new voters wasclearly profound and involved uncharted political territory for all key actors,established or novices. This extraordinary shift in the size of the electorate, in turn,implies that the level of uncertainty for all key actors increased by several orders ofmagnitude.

Consider further the ways in which political leaders and parties could gatherinformation on the distribution of voter preferences in the obvious absence of anyopinion polls, bearing in mind that the meaning of past electoral results had rapidlybecome moot. Since, as observed above, estimates of the likely number of partiescompeting in future elections and the likely effects of different rules hinge cruciallyon the distribution of voter preferences, it is clear that the major political playerswere operating with severely limited information. Further, electoral rules were

1 For three other cases, the big expansion came later: France (1945), Belgium (1949), and Switzerland

(1971).

72 J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

changed by established as well as non-established parties and even by voters. Thus,we would expect that in early 20th Century Europe, just as in late 20th CenturyCentral and Eastern Europe, strategic calculations often became miscalculations, sothat there are many parallels between patterns of electoral reform at the beginningand end of the Century.

As we show below, a closer inspection of electoral choice in the early 20th Centurysuggests that there was far more variation in the conditions of electoral choice acrosscases and far more uncertainty over voter preferences than is generally recognized.Moreover, among the set of cases considered by Boix are several in which reform ofelectoral rules was not on the political agenda, e.g. United States, Canada, Australiaand New Zealand. Including these countries exaggerates the number of instances inwhich a single member district system was actively chosen by party elites. Onceinappropriate cases are set aside (those outside Western Europe), there is only oneinstance (Britain) in which party leaders actually chose to retain SMDP rather thanadopt PR. Elsewhere in Western Europe party elites chose some version ofproportional representation. Given the high levels of uncertainty that elites facedthen, as now, this is the outcome that we would have expected. The question thenbecomes not why some countries adopted PR while others chose to retain SMDP,but instead why Britain alone chose to retain SMDP.

6. Distant miscalculations: the role of uncertainty in early 20th Century Europe

The United Kingdom is an especially important case in this respect. Despiteongoing proposals for electoral reform from the late 19th Century through the early

Year1900 1905 1910 1915 1920 1925

0

25

50

75

100

Votin

g Po

pula

tion

(Ele

ctor

ate

as %

of T

hose

20

or M

ore)

IrelandAustria

Germany

SwedenNorwayDenmarkUnited Kingdom

Italy

BelgiumSwitzerlandFrance

Netherlands

Fig. 1. Expansion of the suffrage, 1900–1925.

73J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

1920s, this was the only country where electoral reform failed. Further, and as notedabove, the United Kingdom was unusual in the sense that the status quo involveda mostly single-member district plurality formula, so that the alternatives were castin a Duverger-style environment. But the case is also noteworthy in the ways itunderscores the kinds of strategic calculations made by all the key actors on the issueunder uncertainty of such magnitude that it led to a major miscalculation for at leastone party, and arguably for another.

Since well before the last major reforms of the 19th Century, those of 1883–1885enacted by William Gladstone’s government, many Liberals had been predisposed tosome form of PR, although these sympathies were subject to considerable qua-lification (Bogdanor, 1981; Hart, 1992). These predispositions were doubtlessreinforced by the results of the general elections from 1886 through 1900, where,despite receiving approximately 45% of the vote each time, the Liberals received lessthan 30% of the seats in all elections except for that of 1892, when they won 40.6%of the seats (Mackie and Rose, 1991, Table 24.3). Indeed, the figures for 1900 shownin the first row of Table 1 typified the Liberal experience, with a seats/votes ratio ofjust 0.61. The figures for 1900 shown in the Table, with a seats/votes ratio of 1.19,also exemplify the Conservative experience of preceding years, and Conservativescontinued to be strong (if not always unanimous) in their support for existingelectoral arrangements.

Perhaps in light of their seats/votes ratios from 1886 to 1900, but certainlyfollowing them, and in anticipation of an election later in the year (one that did notmaterialize), the Liberals in 1903 entered into a pact with Labour (secretly negotiatedbetween Herbert Gladstone and Ramsay MacDonald). The agreement, in effectthroughout the remainder of the decade, enabled Labour (until 1906 actually theLabour Representation Committee) to field most of its candidates without any needto face Liberal opposition (Pelling, 1961). In other words, this was a pact thatenabled the two parties to coordinate against Conservatives.

Against this backdrop, the 1906 general election must indeed have been a pleasantevent for the Liberals. Although their vote share hardly changed from 1900, theywon by a landslide, picking up 215 additional seats (see Table 1). The Conservativevote share fell only slightly from 50.3 to 43.4% (while the Labour vote increased bya similar amount), but Conservatives lost a dramatic 246 seats. The pact thus workedespecially well in its first trial for the Liberals, and as Hart wryly observes, ‘‘fora time after the general election of 1906 many Liberals were disposed to look morecharitably on the existing electoral system than previously’’ (1992, p. 163).

Labour benefited as well. Indeed, in 1906 and the two general elections of 1910,both the Liberals and Labour enjoyed higher seats/votes ratios than did theConservatives. Given the electoral system and Labour’s vote share, such Labourseats/votes ratios would clearly have been impossible absent the pact. In the 1906election, the party fielded a total of just 50 candidates: of the 29 winners, only fivehad Liberal opponents, and in two of these cases the opposition was nominal. In thefirst 1910 election, no successful Labour candidates faced Liberal opposition, whilein the second election of that year, only two Labour candidates experienced suchopposition (Pelling, 1961, pp. 15–24). Even so, the benefit conferred on Labour by

74 J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

the pact was short-term, since the agreement applied to only a limited number of(typically two-member) seats. It thus capped the party’s longer term aspirations forgrowth.

Finally, observe that the Conservatives did poorly in the three elections coveredby the pact between the Liberals and Labour. The coordination between the lattertwo parties held the Conservative seats/votes ratio below 1.0 in each case. Moreover,Table 1 shows that these three elections were the only instances between 1900 and1935 in which this ratio was less than 1.0.

During the war years, the question of electoral reform was much discussed. Itformed the basis of a Speaker’s conference that recommended PR, and culminated inthe Representation of the People Act of 1918 that enacted adult male and limitedfemale suffrage, among other things. The 1918 Act did not, however, include PR(Ogg, 1918). It is useful to consider party support for PR in the debates that precededthe Act. The first three panels of Table 2 show the parliamentary votes by party onproposals that came before the Commons prior to the Act (MPs were given freevotes on these questions).

None of the votes shown in Table 2 reveals majority support for PR. Of moreinterest, perhaps, the three votes reported for 1917 and early 1918 show thatConservative support for the status quo remained broad-based and strong. At theother end of the spectrum, the small Irish Nationalist minority unanimouslysupported PR. But support for PR was mixed among Liberal and Labour MPs.Among Liberal members, this diversity of views was longstanding: although therewere many reformists in the party, the leadership had traditionally been less certainabout PR, a view undoubtedly reinforced by the outcome of the 1906 election. Whilethere was much interest in PR among the Labour rank and file, PR was rejected atthe Party conference of 1914, at the prodding of the Party’s chair, Ramsay

Table 1

Seats/votes ratios and total seats (in parentheses) for Labour, Liberal, and Conservative parties in the UK,

1900–1935

Year Labour Liberala Conservativeb

1900 0.23 (2) 0.61 (184) 1.19 (402)1906 0.90 (29) 1.35 (399) 0.54 (156)

1910(1) 0.89 (40) 0.94 (274) 0.87 (272)1910(2) 0.98 (42) 0.92 (272) 0.87 (271)1918 0.38 (61) 0.86 (163) 1.37 (382)

1922 0.78 (142) 0.65 (115) 1.45 (344)1923 1.01 (191) 0.87 (158) 1.11 (258)1924 0.74 (151) 0.40 (44) 1.42 (415)

1929 1.26 (287) 0.41 (59) 1.11 (260)1931 0.26 (47) 0.80 (32) 1.39 (474)1935 0.66 (154) 0.51 (21) 1.31 (388)

Source: Mackie and Rose (1991, Tables 24.3 and 24.4). Note that, given the introduction in 1918 of adult

male suffrage and restricted female suffrage (women over 30 could vote if they or their husbands were

householders), the size of the electorate almost trebled from 7.7 million in 1910 to 21.4 million in 1918.a Includes Lloyd George Liberals in 1918 and 1922.b Includes Liberal Unionists from 1900 to 1910.

75J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

MacDonald. In his view, PR might help Labour in the short run, but in the longerterm with full adult suffrage ‘‘the plurality system would work to Labour’s ad-vantage, and enable it to squeeze out competitors for the left-wing vote’’ (Bogdanor,1981, p. 125). This strategic position was also endorsed by the Fabians (Hart, 1992,pp. 166–167).2

The 1918 election was the first to be held with nearly full adult suffrage. As is clearfrom Table 1, the Conservatives won a clear majority of seats on the basis of justunder 40% of the popular vote, an outcome that simply reinforced their antipathytoward PR. With the Liberal-Labour electoral pact of 1903 no longer in force, theLiberals garnered a seats/votes ratio of 0.86 to win 163 seats on the basis of about27% of the vote. Thus, their seat losses compared to 1910 were roughlycommensurate with their vote losses, and 1918 saw no change in the Liberal stanceon PR. Labour did poorly: despite a more than trebled vote share, the party wononly 61 seats.

Opinion on PR within both the Liberal and Labour parties was to shiftdramatically over the 6 years after 1918. While the Conservatives retained a clearmajority in 1922, the election itself was a watershed: for the first time, Labour wonmore seats than the Liberals and thus became the principal opposition party (seeTable 1). In the same election, PR was included as part of the independent Liberalparty manifesto, its first appearance in a party program (Hart, 1992). Labourincreased its seat share further in 1923, with a seats/votes ratio greater than 1.0 forthe first time, and Ramsay MacDonald formed a minority government with Liberalsupport.

Six years after 1918, a private member’s bill proposing PR came before theCommons. As the last section of Table 2 shows, Liberals were now (with the benefitof hindsight) almost unanimously in favor of PR. Offsetting this shift, however, was

Table 2

Parliamentary votes in the UK by party on proportional representation

Date: June 1917 Nov 1917 May 1918 May 1924

Vote:a Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No

Party:

Conservative 38 85 29 125 43 104 8 147

Liberal 77 53 57 70 61 55 107 1

Labour 13 11 15 8 7 9 28 90

Irish Nat. 14 0 25 0 0 0 0 0

Other 1 1 2 1 1 1 3 2

Total 143 150 128 204 112 169 146 240

Source: Bogdanor (1981, pp. 130–131, 134).a A vote of ‘Yes’ indicates support for proportional representation.

2 An additional factor complicating the picture was that many members of both the Liberal and Labour

parties were more interested in the alternative vote than in PR, on the grounds that it would increase their

odds of success against Conservatives in constituencies with three-way races. On the alternative vote, see,

e.g. Lijphart (1994, p. 19).

76 J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

Labour support for the existing plurality system by an overwhelming three-to-onemajority. By 1924 PR had thus become a partisan issue, opposed by both theConservatives and Labour, and favored only by the Liberals.

There is little in this chronology that fits well with the arguments advanced byeither Rokkan or Boix. Labour became a powerful force during the 1920s, winninga plurality of seats by 1929, just 11 years after the introduction of adult suffrage.Despite this, there was no movement toward PR of the form anticipated by Rokkan.At the same time, coordination among party elites did not involve an attempt by theestablished parties to collude against the new party, but instead centered on shortterm calculations that involved shifting coalitions. In the first decade of the 20thCentury, Liberals and Labour coordinated with their electoral agreement; during theFirst World War and shortly thereafter, Liberals and Conservatives coordinated inthe coalition government; after 1922, the Conservatives and Labour coordinatedagainst the Liberals on the question of the plurality system.

Thus, each party engaged in strategic behavior to maximize its own short-terminterests. When two parties calculated on the information at hand that coordinationmight help advance their immediate discrete interests, they coordinated; otherwise,they did not. From the figures in Table 1, it is clear that one of the three key parties (theConservatives) had made a better calculation by the mid-1920s than the others, giventhat theConservative seats/votes ratio easily exceeded 1.0 throughout the 1930s.Whilethe results of the 1929 electionmight have suggested that Labour had collectivelymadea good choice in 1924, their experiences in the 1930s would suggest otherwise (unlessone believes theywere employing an even longer time horizon). That the Liberalsmadea mistake by not pushing for PR earlier may have become clear after the fact, but theirstrategy made sense given the information they had at the time.

The United Kingdom is a crucial case since no form of PR was adopted, incontrast to changes that occurred in the rest of early 20th Century Western Europe.Given the role of uncertainty in recent choices of electoral rules in Eastern Europe,we would expect to find a similarly varied and complex pattern in the other earlycases where some form of PR was chosen.

In some instances, electoral reform did not originate with established party elites.For example, Swiss electoral rules changed from a single member district two-ballotsystem to a proportional system as a result of a national referendum. As shown inTable 3, the Radical Democrats had enjoyed comfortable parliamentary majoritiesof around 60% of the seats (based on seats/votes ratios of about 1.2) since the turn ofthe century, which they used to defeat a legislative proposal to amend theconstitution in the summer of 1918. The proposal was then put to a nationalreferendum and became part of federal law in February 1919, prior to the nationalelection held later that year (Gosnell, 1930; Carstairs, 1980, p. 141). Thus, thereferendum was used in this case to circumvent a parliamentary majority.

The German case illustrates another pattern. With the collapse of ImperialGermany after the First World War and the ensuing domestic crisis, the Kaiserappointed the Social Democratic leader as chancellor just before he abdicated. Inone of its first actions, the new Social Democratic government adopted PR byexecutive fiat (recall that the German legislature did not become sovereign until after

77J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

1945). Observe that PR was introduced by a government of the left, in contrast to theBritish experience and notwithstanding the Rokkan-Boix argument (on thesepatterns, see Carstairs, 1980, pp. 162–165; Rustow, 1950). While some have claimedthat PR represented a policy commitment on the part of the Social Democrats, it isalso the case that they had fared poorly under the previous electoral regime. Asshown in Table 4, the average seats/votes ratio for the Social Democrats from 1893through 1912 was about 0.6, while the corresponding figures for the Conservativeand Center Parties were about 1.4.

We could adduce other cases, but the point should be clear. There is little evidencefrom early 20th Century Western Europe that PR was adopted by establishedpolitical interests in an effort to minimize their losses given the expansion of thesuffrage. In the one case where electoral reform failed (the United Kingdom), it wasblocked by an established party along with a newcomer. With the benefit of con-siderable hindsight the Liberal strategy seems foolish while the effectiveness ofthe Labour strategy was hardly self-evident by the 1930s (at the time, of course,

Table 3

Seats/votes Ratios in Federal Elections to the Swiss Nationalrat, 1902–1917

Year

1902 1905 1908 1911 1914 1917 Mean ratio

Party

Radical Democrats 1.19 1.27 1.24 1.22 1.06 1.34 1.22

(59.9) (62.3) (62.9) (60.3) (59.3) (54.5)

Catholic Conservatives 0.94 0.96 1.02 1.05 0.93 1.34 1.04

(21.6) (21.6) (21.0) (20.1) (19.6) (22.2)

Social Democrats 0.33 0.08 0.24 0.40 1.00 0.34 0.40

(4.2) (1.2) (4.2) (7.9) (10.1) (10.6)

Main table entries are seats/votes ratios, and entries in parentheses indicate the share of legislative seats

won. Includes parties that received at least 10% of the votes. Source: Calculated from figures in Mackie

and Rose (1991).

Table 4

Seats/votes Ratios in Elections to the German Reichstag, 1893–1912

Year

1893 1898 1903 1907 1912 Mean ratio

Party

Conservatives 1.34 1.60 1.36 1.61 1.17 1.42

(18.1) (14.1) (13.6) (15.1) (10.8)

Center Party 1.27 1.72 1.27 1.36 1.40 1.40

(24.2) (25.7) (25.2) (26.4) (22.9)

National Liberals 0.88 1.16 0.92 0.94 0.83 0.95

(13.4) (11.6) (12.8) (13.6) (11.3)

Social Democrats 0.48 0.65 0.64 0.37 0.80 0.59

(11.1) (14.1) (20.4) (10.8) (27.7)

Main table entries are seats/votes ratios, and entries in parentheses indicate the share of legislative seats

won. Includes parties that received at least 10% of the votes. Source: Calculated from figures in Mackie

and Rose (1991).

78 J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

uncertainty undermined the effectiveness of these strategic endeavors). In Switzer-land, PR was introduced by referendum, in a move that bypassed the objections ofthe largest established party in the legislature. And in the singular circumstances ofpost-War Germany, a newcomer party (the Social Democrats) found themselves ina position where they could introduce PR by edict.

7. The puzzle of the Boix empirical results

One issue remains. Boix’s (1999) statistical estimates seem to challenge ouremphasis on uncertainty since they indicate that electoral reform was generated bya predictable set of coalitions involving established political parties threatened by newparties of the left in the early 20th Century. In this section, we examine the robustnessof his estimates in some detail to show that the challenge is more apparent than real.

Following Lijphart (1994) and Taagepera and Shugart (1989), Boix’s dependentvariable is the effective electoral threshold, a measure that reflects the proportionalityof the electoral system (the lower the effective threshold, the more proportional thesystem). Party system characteristics are represented as a joint function of theproportion of votes received by parties of the left and the effective number ofestablished non-socialist parties. The subsidiary claim that electoral reform isa function of geographic size (which Boix takes to reflect linguistic and ethnicdiversity) is evaluated using information about the geographical size of countries andan index of ethnic/linguistic fragmentation. Country values for these measures arelisted in Boix (1999 Appendix A).

The first column of Table 5 reports the basic set of OLS estimates employed by Boixand corresponds tomodel (2) in his Table 5.Here, the effective threshold is regressed onleft party strength, old party fragmentation, the product of these two party variables(‘Threat’), and the geographical size of the country (expressed as log10 of the area in 000km2) .3 These estimates appear to offer strong support for Boix’s main argument. Inparticular, the coefficient for Threat is significant beyond the 0.05 level and has thecorrect negative sign, indicating that as the strength of left parties and thefragmentation of old parties jointly increase, the electoral system becomes moreproportional.4 Additionally, the coefficient on size is positive and highly significant,suggesting that increasing size generates more disproportionality. The overall fit of themodel is respectable, with an adjusted R2 of 0.59. Given these estimates, ‘particularlythe statistical strength of the interactive term’, Boix concludes that ‘‘threat is thefundamental factor in determining the choice of an electoral threshold’’ (1999, p. 620).

3 We report OLS estimates to maximize comparability with Boix’s figures, along with Huber-White

standard errors to correct for heteroskedasticity. These standard errors are smaller than their conventional

OLS counterparts employed by Boix, and thus our use of them provides stronger apparent support for his

model than he reported.4 Boix appears concerned that ‘‘against theoretical expectations, the coefficients of socialism and the

effective number of old parties are positive’’ (1999, p. 620). However, these signs are actually consistent

with his theoretical expectations, because the two separate party coefficients cannot be evaluated

individually in a multiplicative model where the effects of each of the party variables are conditional on

each other (see, e.g. Friedrich, 1982).

79J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

There is, however, little reason to take these estimates at face value. A strikingfeature of those figures is that the estimated coefficient for geographic size hasa much larger t-ratio (9.67/1.60=6.05) than the other variables. Observe that thisvariable is geographic size (national acreage), not population size or populationdensity. The question is, what does geographic size reflect? According to Boix, ‘‘sizeis, above all, a proxy for the ways in which ethnic and linguistic fragmentation affectseach country and the means elites devise to deal with it’’ (1999, p. 620).

Accordingly, he generates a new term that is the product of an index of ethnic/linguistic fragmentation and a dummy variable that equals 1 for smaller countries,and zero otherwise. This new term thus specifies an interaction between ethnicdiversity and population size. However, when Boix substitutes this new interactionterm for geographic size, the fit of the model is almost halved: the adjusted R2 incolumn 3 of his Table 1 is 0.33, as opposed to the adjusted R2 of 0.59 in column 2 ofhis Table 5 (or column 1 of our Table 5). In this sense, substituting informationabout ethnic and linguistic fragmentation for geographic size actually diminishes theperformance of the model. Further, as shown in the estimates in the second columnof our Table 5, when geographic size and the ethnolinguistic-size interaction areincluded in the same model, the estimate for the latter is much smaller than itsstandard error while the coefficient for geographic size does not shift, and the modelfit is not improved. This means that geographic size cannot be taken as a proxy forethnic-linguistic fragmentation.5 For better or for worse, and consistent with Blaisand Massicotte (1997), size is clearly the key factor at work, and the size/fragmentation interaction does not belong in the analysis. Clearly, there is no

Table 5

Regressions of the average effective threshold in 1919–1939 on party and social characteristics (N=22)

1 2 3

Threat �40.16* �41.61* �30.22

(10.03) (10.53) (18.94)Left party strength 78.90* 84.27* 36.70

(31.48) (34.41) (65.59)

Number of old parties 8.90* 9.10* 6.36(3.63) (3.62) (6.19)

Geographic size 9.67* 9.00*

(Log10) (1.60) (1.97)Ethnic fragmentation* �6.72area dummy (13.13)

Constant �22.72 �20.92 10.42(13.08) (12.66) (20.14)

R2 0.67 0.67 0.29

Adjusted R2 0.59 0.57 0.17F-ratio 18.08 15.27 13.30

OLS estimates with Huber-White standard errors in parentheses. *P!0.05.

5 Boix (1999, p. 620) uses the same test to conclude that geographic size is not a proxy for trade

openness.

80 J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

support in these data for the treatment of country size as a proxy for ethnic/linguisticfragmentation.

We are, indeed, at a loss to identify the mechanism by which geographic sizemight plausibly be said to impinge on the electoral threshold. Further analyses, notdisplayed here, indicate that it is not serving as a proxy for population size or forpopulation density. Acreage alone appears to be the thing, a regularity that isdifficult to explain.

At the same time, sheer geographic size does play a key role in Boix’s empiricalanalysis. Observe the estimates in column 3 of Table 5, which correspond to those inthe first and third columns, except that they do not include either of the country sizeterms. Here we see that when considered by themselves, neither of the two individualparty terms nor their product has a systematic effect on the size of the effectivethreshold. Indeed, compared with the figures in column 1, the fit of the model incolumn 3 plummets (the adjusted R2 drops from 0.59 to 0.17), and the estimatedThreat coefficient in column 3 is appreciably smaller than that shown in column 1.The inclusion of country size is thus crucial to Boix’s analysis in the sense that itdrives his statistical estimates. With this variable excluded, there is little basis for hisprincipal claim, noted above, that ‘‘threat is the fundamental factor in determiningthe choice of an electoral threshold’’.6 More broadly, this means that there is nobasis for the claim that electoral reform was generated by a predictable set ofcoalitions involving established political parties threatened by emerging parties ofthe left in the early 20th Century.

8. A simpler formulation

Consider now a much simpler model of electoral rule choice, one that takes intoaccount the impact of extreme uncertainty. Our reanalysis of Boix’s statistical resultsreinforces our view that long-term coordination among established parties is unlikelyin an uncertain environment. At the same time, to say that the strategic capabilitiesof all parties involved, whether established or emerging, is limited by a general lackof information is not to preclude strategic calculations.

Accordingly, we posit a model based on the simplest kind of strategic, seat-maximizing behavior possible: all parties base their support or opposition toa change in electoral rules in light of their performance (as manifested in their seats/votes ratios) under current rules in the previous election. Observe that this involvesshort-term calculations, since we expect longer-term calculations to be shrouded ineven more uncertainty. We hypothesize that as the ratio of seats to votes for thelargest party increases, that party’s support for an electoral system with a highelectoral threshold (such as an SMDP system) also increases, whether or not thatparty is old and established or new. By the same token, as the seats/votes ratio of thelargest party decreases, that party’s support for an electoral system with a lowelectoral threshold (such as some form of PR) should increase, regardless of its

6 We emphasize that it is geographic size, not the size/fragmentation interaction, that is crucial here.

81J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

ideological composition. Implicit in this formulation is the proposition that thelargest party in parliament has the most influence on any decision to change theelectoral rules.

Observe that this formulation is consistent withBenoit (2004) and also runs throughour earlier analyses of particular cases. Barring the three elections in which they facedstrategically coordinated behavior from their opponents, the British Conservativesenjoyed seats/votes ratios in excess of 1.0 from 1900 through 1935, and they stronglyopposed any rule change. The Swiss Radical Democrats enjoyed similarly high ratiosfrom 1902 through 1917, so that reform came over their objections by means ofa national referendum. And the German Social Democrats introduced PR onachieving office after the Kaiser’s abdication, having experienced seats/votes ratios ofless than 1.0 in each of the five previous elections in which they had participated.

In Table 6, we display estimates for a model of electoral rule choice given theseats/votes ratio of the largest party in parliament, whether that party was anestablished conservative party or a new socialist or social democratic party (as wasthe case in six of the twenty countries included in the analysis). Focusing solely onthe choice of electoral rules in the pre-WWII period, we use twenty of Boix’s originaltwenty-two cases. We exclude Spain and Greece on the following grounds. Spain’sinter-war democratic period lasted only 5 years and ended in a military dictatorship.Greece’s inter-war democratic period lasted a little longer (10 years) but also endedin a military dictatorship. Moreover, Greek electoral rules were highly fluid duringthis period.7 Thus, for this case, analyses are highly sensitive to the choice of electionfrom which to start one’s analysis.

Table 6

Regressions of the average effective threshold in 1919–1939 on seats/votes ratio of largest party (N=20)

1 2 3

Seats/votes ratio 31.93* 27.45* 27.66*

Of largest party (11.21) (11.20) (13.78)

Threat �15.71

(31.17)

Left party strength �4.89

(93.63)

Number of old parties 4.59

(9.84)

Geographic size 4.20*

(Log10) (0.80)

Constant �20.91 �38.53* �17.35

(12.04) (12.94) (29.55)

R2 0.21 0.61 0.38

Adjusted R2 0.16 0.57 0.22

F-ratio 4.73 13.48 3.34

OLS estimates with Huber-White standard errors in parentheses. *P!0.05.

7 The extreme volatility of Greek electoral law in the inter-war years is shown in Boix (1999, Fig. 7).

For discussion of the shifts involved, see Vegleris, 1981, pp. 219–234) and Mavrogordatos (1983, esp.

chapter 7 and Appendix 1).

82 J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

The estimates shown in Table 6 are consistent with our hypothesis. Specifically, asshown in the first column, the seats/votes ratio of the largest party in parliament hasa significant and positive effect on the choice of electoral system (as measured by theelectoral threshold, following Boix). Further, as one can see by comparing the firsttwo columns in the table, this effect of the seats/votes ratio of the largest party doesnot hinge on the inclusion of a variable measuring the geographic size of our countrycases. In this sense, the effect is more robust than those reported by Boix. Finally, thethird column of Table 6 shows that our simple explanation is robust to the inclusionof the three main explanatory variables from Boix’s argument, ‘threat’, ‘size of thelargest left party’, and ‘effective number of old parties’. In other words, in thepresence of our key explanatory variable and absent the irrelevant influence ofgeographic size, Boix’s key variables do not systematically influence the electoralthreshold.

Given the level of uncertainty involved in changing electoral rules, we wouldexpect the seats/votes ratio of the largest party to have a systematic effect on theelectoral threshold. That parties’ support for a new set of electoral rules hingessystematically on how they have recently performed under the existing procedureseems about the best that they can do, and it is a result in keeping with recentanalyses of rule choice in emerging democracies. Thus, an explanation that demandsmuch less on the part of party elites performs better than an explanation thatassumes the availability of sufficient information to support complex strategiccoordination.

These results imply that the sole occasion one would expect a country to retaina single member district system is when the largest party benefits substantially fromthe current electoral rules, so much so that it can control or dominate the choice ofelectoral rules. This was the case only in Britain (see the last column of Table 1above); hence, it alone among West European democracies chose to retain SMDP.Thus, our results are broadly compatible with the empirical preponderance of PR asreported by Cox (1997); further, our estimates are consistent with the predictions ofShvetsova’s model (2003).

9. Conclusion

The proposition that reform of electoral systems in early 20th Century WesternEurope was driven by a distinctive set of forces has a long pedigree originating withRokkan’s (1970) classic treatment and manifested most recently in Boix’s (1999)empirical analysis. We agree with these accounts that party leaders in the periodattempted to behave strategically. What is not clear, however, is how they could doso effectively given the extreme uncertainty they confronted. Further, we have shownthat the statistical evidence for the Rokkan-Boix argument is not robust. We havealso shown that a model employing a much simpler decision rule is more consistentwith the available data. In our view, when uncertainty is taken seriously, the earlyperiod of electoral reform closely parallels the more recent experience in Central andEastern Europe, obviating the need to treat the first period as distinctive.

83J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

In his ‘Comment on Institutional Change’, Shepsle (2001) casts institutionalreform as a ‘multi-dimensional’ game that involves many players, many possibleoutcomes, and many different participants. He concludes that, as a result, ‘it comesdown to information’ (pp. 324–325). That is, the ability of key actors to change therules to benefit themselves is limited by the information they have on all relevantdimensions. As we have emphasized, periods of electoral reform typically occur asa component of larger political transformations in which uncertainty becomesendemic. Accordingly, designers of electoral systems have historically not had accessto the information necessary for them effectively to choose electoral rules from whichthey would benefit. During periods of major political transformation, politicalparties come and go, voter preferences change often and rapidly, and complexelectoral rules along with their consequences are poorly understood. Thus, any effortto explain the choice of electoral rules as a predictable strategic response to electoralthreat by a stable set of actors (established parties) must be viewed with skepticism.As we have shown in our discussion of the cases, electoral rules were changed byboth established and new parties in both periods of electoral reform. Further, oursystematic analyses of data from the early 20th century suggests that political elitesengaged in only short-term strategic behavior; that is, their support for any electoralsystem depended on how well they had fared in the previous election. Even so,uncertainty made it difficult (or even impossible) for party elites in either period torealize the gains they anticipated from their strategic choices.

Acknowledgements

We thank the referees for their very helpful comments and the UC DavisAcademic Senate for its support.

References

Bartolini, S., 2000. The Political Mobilization of the European Left, 1860–1980: The Class Cleavage.

Cambridge University Press, New York.

Benoit, K., 2004. Models of electoral system change. Electoral Studies, (in press).

Blais, A., Massicotte, L., 1997. Electoral formulas: a macroscopic perspective. European Journal of

Political Research 32(August), 107–129.

Bogdanor, V., 1981. The People and the Party System: The Referendum and Reform in British Politics.

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Boix, C., 1999. Setting the rules of the game: The choice of electoral systems in advanced democracies.

American Political Science Review 93(September), 609–624.

Carstairs, A.M., 1980. A Short History of Electoral Systems in Western Europe. Allen & Unwin, London.

Colton, T.J., 2000. Transitional Citizens: Voters and What Influences Them in the New Russia. Harvard

University Press, Cambridge.

Cox, G.W., 1997. Making Votes Count: Strategic Coordination in the World’s Electoral Systems.

Cambridge University Press, New York.

Duverger, M., 1954. Political Parties: Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State. Wiley,

New York.

84 J.T. Andrews, R.W. Jackman / Electoral Studies 24 (2005) 65–84

Elster, J., Claus, O., Ulrich, K.P., 1998. Institutional Design in Post-communist Societies: Rebuilding the

Ship at Sea. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Friedrich, R.J., 1982. In defense of multiplicative terms in multiple regression equations. American

Journal of Political Science 26, 797–833.

Geddes, B., 1996. Initiation of new democratic institutions in Eastern Europe and Latin America. In:

Lijphart, A., Waisman, C.H. (Eds.), Institutional Design in New Democracies: Eastern Europe and

Latin America. Westview Press, Boulder, CO.

Gosnell, H.F., 1930. Popular participation in Swiss National Council elections. American Political Science

Review 24, 426–439.

Hart, J., 1992. Proportional Representation: Critics of the British Electoral System 1820–1945. Clarendon

Press, Oxford.

Kaminski, M.M., 2002. Do parties benefit from electoral manipulation? Electoral laws and heresthetics in

Poland, 1989–1993. Journal of Theoretical Politics 14(3), 325–358.

Lijphart, A., 1992. Democratization and constitutional choices in Czecho-Slovakia, Hungary and Poland,

1989–1991. Journal of Theoretical Politics 4(2), 207–223.

Lijphart, A., 1994. Electoral Systems and Party Systems: A Study of Twenty-seven Democracies,

1945–1990. Oxford University Press, New York.

Mackie, T.T., Rose, R., 1991. The International Almanac of Electoral History. third ed. CQ Press,

Washington, DC.

Mavrogordatos, G.Th., 1983. Stillborn Republic: Social Coalitions and Party Strategies in Greece,

1922–1936. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Moraski, B., Loewenberg, G., 1999. The effect of legal thresholds on the revival of former communist

parties in East-Central Europe. Journal of Politics 61, 151–170.

Moser, R.G., 2001. Unexpected Outcomes: Electoral Systems, Political Parties, and Representation in

Russia. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh.

Ogg, F.A., 1918. The British Representation of the People Act. American Political Science Review 12,

498–503.

Pelling, H., 1961. A Short History of the Labour Party. Macmillan, London.

Przeworski, A., 1991. Democracy and the Market. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Remington, T.F., Smith, S.S., 1996. Political goals, institutional context, and the choice of an electoral

system: the Russian parliamentary election law. American Journal of Political Science 40, 1253–1279.

Rokkan, S., 1970. Citizens, Elections, Parties: Approaches to the Comparative Study of the Process of

Development. Universitetsforlaget, Oslo.

Rustow, D.A., 1950. Some observations on proportional representation. Journal of Politics 12, 107–127.

Shepsle, K.A., 2001. A comment on institutional change. Journal of Theoretical Politics 13(3), 321–325.

Shvetsova, O., 2003. Endogenous selection of institutions and their exogenous effects. Constitutional

Political Economy 14, 191–212.

Taagepera, R., Shugart, M.S., 1989. Seats and Votes: The Effects and Determinants of Electoral Systems.

Yale University Press, New Haven.

Vegleris, P., 1981. Greek electoral law. In: Penniman, H.R. (Ed.), Greece at the Polls: The National

Elections of 1974 and 1977. American Enterprise Institute, Washington, DC, pp. 21–48.

White, S., Rose, R., McAllister, I., 1997. How Russia Votes. Chatham House, Chatham, NJ.